Abstract

Prior research found that without the naming cusp, children did not learn from instructional demonstrations presented before learn units (IDLUs) (i.e., modeling an expected response twice for a learner prior to delivering an instructional antecedent), however, following the establishment of naming, they could. The present study was designed to compare the rate of learning reading and mathematics objectives in children who showed naming using IDLUs compared to standard learn units (SLUs) alone (comparable to three-term contingency trials). In Phase 1, a pre-screening phase, we demonstrated that four typically developing males, 3 to 4 years of age, had naming within their repertoire, meaning they were able to master the names of novel 2-D stimuli as both a listener and a speaker without explicit instruction. Using the same participants in Phase 2, we compared rates of learning under two instructional methods using a series of repeated AB designs where conditions (IDLUs versus SLUs) were counterbalanced across dyads and replicated across participants. The participants learned more than twice as fast under IDLU conditions and showed between 30% and 50% accuracy on the first presentation of a stimulus following a model. The IDLU condition was more efficient (fewer trials to criterion) than the SLU condition. These findings, together with prior findings, suggest that the onset of naming allows children to learn faster when instructional demonstrations are incorporated into lessons.

Keywords: Teacher models, Instructional demonstrations, Naming, Accelerated learning, Verbal behavior development theory

Theories of interaction between development and instruction have a long history in developmental psychology and education. Gewirtz, Bijou, and Baer (Bijou & Baer, 1961; Gewirtz & Baer, 1958) were among the earliest researchers to study development from a behavior-analytic perspective. Following this groundwork, Rosales-Ruiz and Baer (1997) proposed that the behavioral approach to development should focus on the onset of critical behaviors that they identified and defined as behavioral developmental cusps. These cusps consisted of any critical behavior change that brought the organism’s behavior into contact with new contingencies that have even more far-reaching consequences (e.g., learning to crawl, or first instances of speech that affect the behavior of a listener). Once such cusps are demonstrated, children can learn things they could not prior to their instantiation, or may learn at faster rates.

Research in behavior analysis focusing on verbal behavior and its development has identified verbal behavior developmental cusps, thus joining the study of Skinner’s theory of verbal behavior (1957), relational responding (Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Cullinan, 2000; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), teaching as behavior analysis (Greer, 2002; Skinner, 1968), and behavioral analyses of development (Bijou & Baer, 1961; Gewirtz & Baer, 1958; Greer & Ross, 2008). The identification of behavioral developmental cusps has allowed scientists and researchers alike to study development in ways that hold promise for identifying development by instruction interactions (Novak & Pelaez, 2004). Many examples have been provided within the literature demonstrating that prior to the establishment of certain cusps, children did not learn, or learned very slowly, even when best practice operant teaching procedures were used (Greer & Han, 2015; Greer, Pistoljevic, Cahill, & Du, 2011b; Pereira-Delgado, Greer, & Speckman, 2008; ). Some of these cusps identified in the research also meet the criterion for new learning “capabilities” (Cahill & Greer, 2014; Greer & Keohane, 2005; Greer & Longano, 2010; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer & Speckman, 2009). Verbal behavior development (VBD) capabilities not only allow children to learn things they could not before (like a cusp), or learn them significantly faster (like a cusp), but also to learn in a different way (e.g., from observing models, watching others be instructed, or learning object-word relations incidentally).

One such cusp that is also a capability that allows children to learn in new ways is naming (Horne & Lowe, 1996) which is the focus of the research reported herein. The term naming is used to describe a VBD cusp that is also a capability, which allows children to learn object-word relations as both listener (i.e., selection or point to responses) and speaker (vocally producing responses) incidentally. Children who demonstrate the naming cusp can learn the names of things as a listener or speaker without direct instruction, instructional reinforcement, or the observation of the consequences of instruction, and are capable of developing complex social language (Greer & Du, 2015).

There is considerable evidence that the onset of naming results in the incidental learning of object-name relations as well as what those objects do (i.e., as a listener, a speaker, and as intraverbal tacts). How this behavioral developmental cusp influences teaching procedures has also been the focus of research. Studies suggest that the presence or absence of naming directly affects whether a child can learn from observing a teacher modeling a skill. As such, naming has been proposed as a critical component of whether a child will benefit educationally from settings where whole group instruction comprised of modeling target responses are used (Corwin & Greer, in press; Greer, Corwin, & Buttigieg, 2011a). Greer et al. (2011) found that preschoolers who lacked naming required extensive instruction in order to master educational objectives. Unlike children with naming, children who lacked naming could not learn from observing the teacher’s instructional-demonstrations. Children without naming could only emit correct responses after experiencing direct contingencies of reinforcement or corrections (i.e., basic learn units). In the second experiment, the researchers found that the children who lacked naming could learn from IDLUs after the establishment of the naming cusp. Corwin and Greer (in press) extended these findings while also replicating the effects of MEI on instantiation of the naming cusp.

Research on instructive feedback has shown that presenting additional non-target stimuli during the antecedent and consequence events of instruction (much like the IDLU procedure in this experiment), can lead to the acquisition of those targets post instruction without having been directly taught (Vladescu & Kodak, 2013; Wolery, Schuster, & Collins, 2000). With instructive feedback, additional information (or secondary target) is presented without additional training, whereas when an IDLU procedure is used, two models of the correct response are given and then the same target is directly taught (often using multiple exemplars). In general education classrooms comprised of mainly typically developing children, teachers often deliver instructions that involve physically modeling or delivering spoken directions for correct responses to tasks. Brophy and Good (1986) theorized that the initial presentation of information maximizes student achievement, supporting teachers’ use of demonstrations with spoken instruction. Similarly, Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) reported that more learning occurs in the presence of teacher modeling, than in its absence. If students cannot learn from observing models and following spoken instructions, this type of instruction is not effective, as some of the above studies report. If students can learn from models, this type of instruction may be more efficient than instruction involving only direct consequences of reinforcement or error correction procedures. In the following experiment, we tested the extent to which it is more efficient to use IDLUs than standard learn units (SLUs) when teaching children who have the naming cusp.

The study consisted of two phases. Phase 1 was a pre-screening phase during which the experimenters showed that all four participants had the full naming cusp within their repertoires, thus making them appropriate candidates for Phase 2, the experimental portion of the study. This decision was based on the participants’ rates of acquisition for learning the names of novel stimuli through the use of a naming experience procedure, and was measured by their responses during listener and speaker probes. Based on previous research conducted by Greer et al. (2011) and Corwin and Greer (in press), it was hypothesized that because these participants had reliably demonstrated they could learn language incidentally (i.e., through the naming cusp), they would benefit from the use of IDLUs over the use of SLUs. Prior research found that the onset of naming was functionally related to learning from IDLUs; however, the extent to which rates of learning might be more efficient under IDLU conditions was not tested.

Method

Participants

Four typically developing preschool males were selected for participation in both phases of the study. Participant A was 4.10 years old, Participant B was 3.6 years old, Participant C was 3.10 years old, and Participant D was 3.1 years old. All participants were selected from a preschool integrated classroom that implemented tactics and principles from the science of behavior analysis. The classroom was part of a privately managed but publicly funded school for children with and without disabilities located outside of a major metropolitan area. All participants came from families that had an income status of professional, and were hypothesized to have the verbal developmental cusp of naming within their repertoire, which was subsequently demonstrated by the results of the pre-screening phase. In Phase 2, Participants were divided into dyads. Dyad 1 consisted of Participants A and B, while Dyad 2 consisted of Participants C and D.

Setting and Materials

All pre-screening sessions and probes in Phase 1 took place in the free-play area of the participants’ classroom. Materials included multiple exemplars of novel 2-D stimuli on index cards (i.e., multiple colors and sizes of different symbols on identically-sized white notecards) and preferred toys. Table 1 contains information on the 2-D stimuli used to screen each participant.

Table 1.

Two-dimensional target stimuli selected for naming experiences for each participant and the range of naming experience sessions required for each participant to learn object-name relations in Phase 1

| Participant | Stimulus 1 | Stimulus 2 | Stimulus 3 | Stimulus 4 | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | # (Pound) | ₺ (Lira) | ~ (Tilde) | & (Ampersand) | 5 (no range) |

| Participant B | # (Pound) | ₺ (Lira) | ~ (Tilde) | % (Percent) | 5-15 |

| Participant C | Ω (Omega) | ₺ (Lira) | ~ (Tilde) | % (Percent) | 5-20 |

| Participant D | # (Pound) | ₺ (Lira) | ~ (Tilde) | % (Percent) | 15-25 |

All sessions during Phase 2 were conducted within the participants’ classroom. The participants were seated in child-sized chairs at their individual desks that were arranged in groupings of four or five desks. The experimenters were seated in the center of each grouping of desks to facilitate delivery of instruction to different participants. Participants were given instruction on an individual basis; however, other classmates completed independent work alongside them. Materials consisted of the following: Small personal whiteboards on which participants could write their responses, dry erase markers and erasers, an easel for the teacher to write instructions, small manipulatives (i.e., blocks, counting bears, etc.) that were occasionally used for certain objectives (see Table 2), and preferred stimuli (i.e., toys, edibles, etc.) that were used as reinforcers after each instructional session.

Table 2.

Outline of design and sequence of curricular objectives taught in Phase 2

| Phase | SLU | IDLU |

|---|---|---|

| Participant A (ABAB sequence) |

Reading A1: - Apostrophes - Advanced sight words Reading A2: - Past/present tense - Advanced sight words Math A1: - 2 digit addition - Rounding to the nearest 10 Math A2: - Carrying - Tacting large numbers |

Reading B1: - Tacting nouns - Advanced sight words Reading B2: - ‘i before e’ rule - Advanced sight words Math B1: - Subtraction - Odd/even numbers Math B2: - Algebra (simplifying symbol equations) - Multiplication |

| IDLU | SLU | |

| Participant B (BABA sequence) |

Reading B1: - Tacting phonemic CVC words - Advanced sight words Reading B2: - Tacting verbs - Advanced sight words Math B1: - Single digit addition - Number families 1-5 Math B2: - Tacting large numbers - Algebra (simplifying symbol equations) |

Reading A1: - Tacting nouns - Advanced sight words Reading A2: - Tacting number of syllables - Advanced sight words Math A1: - Single digit subtraction - Rounding to the nearest 10 Math A2: - Grouping numbers (simple division) - Fractions with symbols |

| SLU | IDLU | |

| Participant C (ABAB sequence) |

Reading A1: - Beginning sounds - Sight words Reading A2: - Tacting verbs - Sight words Math A1: - Tacting ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ addition - Rounding to the nearest 10 Math A2: - Grouping numbers - Addition (+1) problems |

Reading B1: - Tacting nouns - Sight words Reading B2: - Tacting syllables - Sight words Math B1: - Tacting more or less - Number sequences Math B2: - Single digit subtraction - Tacting large numbers |

| IDLU | SLU | |

| Participant D (BABA sequence) |

Reading B1: - Tacting beginning letters of words - Sight words Reading B2: - Ending sounds - Sight words Math B1: - Tacting more than - Counting 3D objects (1-4) Math B2: - Measuring with cubes - Sequencing numbers (1-10) |

Reading A1: - Beginning sounds - Sight words Reading A2: - Syllables - Sight words Math A1: - Tacting less than - Responding with number of 3D objects (1-3, VF of 5) Math A2: - Tacting big numbers - Tacting numbers (1-10) |

Phase 1: Pre-screening

Target Responses and Measures

To ensure the presence of naming, we measured the number of exposures that were required for participants to learn the names of novel 2-D stimuli as both a listener and a speaker, incidentally. This was achieved by assessing point-to (listener) and intraverbal tact (see and say speaker) responses for each 2-D stimulus during post-naming experience probes (Cahill & Greer, 2014; Gilic & Greer, 2011).

Naming experience sessions were used to test for the presence of naming. A naming experience was defined as an experimenter “playing” with a 2-D stimulus such that a participant was given the opportunity to visually observe and hear the name of the stimulus simultaneously. “Playing” occurred via incorporating 2-D stimuli into play scenarios with participants’ preferred toys and items (i.e., “Look, percent is going in the truck” or “Don’t let the dinosaur eat tilde!”). One naming experience session consisted of a total of 20 exposures (four different stimuli, each presented five times). For the purpose of this study, one naming experience session was defined as the entire block of 20 single exposures. Exposures referred to each individual instance of hearing a name while observing the corresponding stimulus within any given session (i.e., one naming experience session consisted of 20 single exposures).

Pre-screening Procedure

The pre-screening phase consisted of three parts: 1) pre-naming experience probes to identify novel 2-D stimuli (i.e., stimuli that were not already within the child’s repertoire), 2) naming experience sessions for the designated novel stimuli, and 3) post-naming experience probes to assess whether the names of the stimuli were acquired. Post-naming experience probes were comprised of two opportunities to respond as a listener and two opportunities to respond as a speaker.

Pre-naming Experience Probes

Prior to conducting naming experience sessions, experimenters identified 2D non-contrived stimuli that participants could not respond to as a listener or a speaker. Unconsequated probe trials for listener responses consisted of asking the participant to point to a target 2-D stimulus within a counterbalanced array of three stimuli (one target stimulus and two non-target stimuli, all hypothesized to be unknown). A correct response was defined as the participant pointing to the correct stimulus within 3 s. An incorrect response was defined as the participant pointing to the incorrect stimulus or not emitting a response within 3 s. Unconsequated probe trials for speaker responses consisted of presenting one 2-D stimulus and asking the participant “What is this?” while holding or pointing to the target stimulus. A correct response was defined as the participant’s vocal emission of the correct name for the stimulus within 3 s. An incorrect response was defined as the participant emitting a contrived or otherwise non-target name for the stimulus, or not emitting a response within 3 s. This procedure was repeated until four stimuli that a participant could not respond to as a listener nor speaker were identified for use in subsequent naming experience sessions (see Table 1). Each stimulus was tested three times for listener responses and three times for speaker responses before determining that the stimuli were unknown to the participant(s). A score of 0 out of 3 for both listener and speaker probes indicated that a stimulus was unknown.

Naming Experience Sessions

Naming experience sessions consisted of participants’ observation of four different, novel 2-D stimuli in a free-play setting. Correct responses were defined as listener responses during which the participant looked at the target stimulus as an experimenter said its name. Experimenters recorded a plus on the data sheet if the participant looked at the stimulus while simultaneously hearing its name. If a participant did not look at a target stimulus while an experimenter said its name, experimenters marked a minus on the data sheet and proceeded to gain the participant’s attention by saying his name or providing the opportunity to mand for a desired item before re-presenting the target stimulus. For a naming experience session to be complete, participants were required to observe each 2-D stimulus five times. The number of attempted exposures varied from session to session depending on how many minuses occurred before achieving the 20 successful exposures. For example, if Participant A did not look at the index card with a percent sign on it two times during the session while the name was being spoken, but did successfully observe all other stimuli while their names were being spoken, that session would consist of 22 exposure attempts (20 successful exposures and 2 unsuccessful exposures). The 20 successful exposures did not need to be consecutive, however 5 total successful exposures needed to happen per stimulus.

Post-naming Experience Probes

Following the completion of each naming experience session, post-naming experience probes were conducted on the same day. Experimenters waited one hour following the naming experience sessions before conducting probes on the participants’ listener and speaker responses for each of the four novel stimuli per participant. These probes consisted of one listener probe for each of the four stimuli, followed by one speaker probe for each of the four stimuli. This procedure was then repeated a second time to test for the transfer from listener to speaker behaviors (i.e., two probes of each type, listener and speaker, were conducted on each target for a total of 16 probes per participant). Prior work has shown that listener responding can occasion speaker responding consistent with the bidirectional nature of the naming cusp (Kobari-Wright & Miguel, 2014). Criterion for learning the name of a stimulus was defined as emitting a correct response as both a listener and a speaker for the given stimulus within 3 s. Neither correct nor incorrect responses were consequated (i.e., responses were put on extinction) during probe sessions. Criterion was met if a correct listener and speaker response was recorded for all four stimuli. If accuracy for fewer than four stimuli occurred during a probe session, the naming experience procedure continued with all four stimuli; however, only data on stimuli for which criterion had not yet been met were recorded during the subsequent naming experience session(s) and post-naming experience probes. Following identification of participants with naming using the aforementioned procedures, Phase 2 commenced.

Phase 2: Comparison of Instructional Methods

Target Responses and Measures

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was the cumulative number of learn units required to achieve mastery for reading and mathematics objectives under two types of instruction: 1) standard learn unit instruction (SLU), and 2) instructional demonstrations followed by learn units (IDLUs). This dependent variable was also analyzed, summarized, and reported in the following ways in the results section: 1) The number of learn units required to master objectives within each session block, and 2) the cumulative record of correct responses to master each objective, 3) the mean number of learn-units-to-criterion for each method, and 4) the participants’ mean correct responding during first trials and during first session blocks for both SLU and IDLU conditions.

Objectives were individualized across participants based on their unique skill deficits. Skill deficits were identified during baseline screening sessions and were then matched in terms of difficulty and randomly assigned to the SLU or IDLU condition. Objectives required a variation of both listener and speaker responses. For example, a sequencing pictures program would require a listener response while a tact program would require a speaker response. However, due to the presence of naming, it was assumed that participants would be able to respond as either a listener or a speaker to any instruction that may have required both response topographies.

Each objective consisted of a set of four exemplars of that task, each presented five times to create a 20-trial session block. This was consistent across both conditions. For example, for number sequencing between 0-5, the experimenter would have the participant sequence the numbers 0-2, 1-3, 2-4, and 3-5 each 5 times for a total of 20 trials.

Independent Variable

The independent variable was the instructional condition, which consisted of either SLU presentations or IDLU presentations for teaching mathematics and reading objectives. See Table 3 for examples of the antecedents for SLUs and IDLUs across different academic objectives. For both methods of instruction, mastery criterion was set at 90% or above correct responding for one IDLU session consisting of a 20-trial block or for one SLU session consisting of a 20-trial block.

Table 3.

Examples of antecedents across select objectives for both conditions in Phase 2

| Academic Domain | Exemplar Objective | Condition | Antecedent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | Sequencing | SLU | Teacher: “Put these numbers in order” (gives student 3 numbers) |

| IDLU | Teacher: “I’m going to show you how to put these numbers in order: First comes 1, then 2, then 3. Now I’m going to show you a different example: First comes 5, then 6, and then 7. Now you put these numbers in order” (gives the student 3 new numbers, for example 8, 9, and 10) | ||

| Single-Digit Addition | SLU | Teacher: “Add these numbers” (gives the students a small personal white board with a single-digit addition problem on it, for example 1 + 2 = __) | |

| IDLU | Teacher: “I am going to show you how to add these numbers: 1 + 2 = ___. First you draw lines under the second number (i.e., under 2). Then you count from the first number upwards using the lines you drew, 1, 2, 3. So, 1 + 2 = 3. Here is another example” (this repeats with a new problem, for example 2 + 2 = __). “Now it’s your turn” (gives the student a new problem, for example 1 + 3 = ___) | ||

| Tacting More/Less | SLU | Teacher gives student two piles of manipulatives and asks “Which pile has more?” or “Which pile has less?” | |

| IDLU | Teacher: “I am going to show you what more and less means using these bears. First I am going to show you an example of more. This pile has 5 and this pile has 10. 10 is more than 5. Now I am going to show you what less means. This pile has 8 and this pile has 4. 4 is less than 8. Now your turn” (teacher gives student two piles that differ in quantity than the examples just provided, like 6 and 3) | ||

| Reading | Sight Words | SLU | Teacher holds up an index card with a word written on it and waits for the student to emit the tact for the word |

| IDLU | Teacher chooses 4 target words. Teacher then says “These words say and, but, if, and that. Again, these words say if, and, that, and but.” Then the teacher holds up one of the sights words that was not the last one provided and waits for the student to textually respond to the word, and so on | ||

| Nouns | SLU | Teacher writes three words on a small white board and reads the words to the student, for example, drinking, kicking, and chair, then asks, “Which word is the noun?” | |

| IDLU | Teacher says, “Nouns are words that are people, places, or things. If I say drinking, kicking, and chair, which word is a noun? Chair is, because a chair is a thing. Here is another example: Nouns are words that are people, places or things. If I say hot, cold, or Mom, which one is a noun? Mom is, because Mom is a person. Now your turn” (teacher then gives the student a new example and provides the student with the opportunity to respond) | ||

| Tacting Beg. Sounds | SLU | Teacher provides the student with three sounds and then asks “What sound do those words begin with?” For example: “Boat, bat, and ball: What sound do those words begin with?” | |

| IDLU | Teacher says “Boat, ball, and bat. All those words begin with the sound “buh”. Here is another example: Hit, hat, and hoop. All those words begin with the sound “huh”. Now your turn” (teacher provides the student with the opportunity to respond to a new target beginning sound independently) |

*Note. Participants were not given the opportunity to respond to the models and the first learn unit following a model was always different from the last exemplar provided in the model

Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

IOA was calculated by dividing the number of intervals of agreement of correct or incorrect responses emitted by each participant, by the total number of intervals and multiplying the result by 100. An agreement consisted of two independent observers agreeing that a participant had emitted a correct response based on the antecedent given. Correct responses were pre-determined and operationally defined prior to beginning the study. A disagreement consisted of one observer having considered a response to be correct while the second observed considered the response to be incorrect. In Phase 1, for Participants A and B, in vivo IOA was assessed using the trial-by-trial method for 100% of naming experience sessions with 100% agreement, and 100% of post-naming experience probe sessions with 100% agreement. For Participants C and D, IOA was assessed for 86% of naming experience sessions with 100% agreement and 86% of post-naming experience probe sessions with 100% agreement. In Phase 2, in vivo trial-by trial IOA was collected for 39% of SLU presentations for all participants with 100% agreement. IOA was calculated for 38% of IDLU presentations for all participants with 100% agreement.

Design

A series of AB designs (Kennedy, 2005) repeated within and counterbalanced between participants were used to demonstrate the efficiency of IDLU instruction over SLU instruction. Non-equivalent sets were used due to reasons pertaining to social validity, however the sets were matched across participants as best as possible. Because participants were in a school setting, continued mastery of their curricular goals within the classroom at a level that suited their individual skill sets was important. The design was counterbalanced such that Participants A and C began instruction for two separate objectives in mathematics and two separate objectives in reading under the SLU method of instruction, whereas Participants B and D began instruction for two separate objectives in both mathematics and reading under the IDLU method of instruction. Once both objectives were met for both mathematics and reading under the assigned method of instruction, the participants switched methods and began instruction under the new method. This continued until all participants had met two objectives in both mathematics and reading twice under each method of instruction (i.e., A1B1A2B2 for Participants A and C, and B1A1B2A2 for Participants B and D, where A is the SLU and B is the IDLU and 1 and 2 refer to different objectives). The design resulted in a simultaneous between and within-subjects analysis. This reversal occurred three times for each dyad (see Table 2 for the sequence the specific objectives used for each participant).

Once a participant had responded with 90% accuracy during one block, the objective was considered mastered. Two objectives were run simultaneously under one condition until both objectives were mastered. Objectives were taught in blocks of 20 trials however trials for different targets were interspersed during training sessions. Only one block of 20 trials (i.e., one session) was completed for each objective per participant per day so as to ensure that the remaining objectives within the participants’ curricula were not neglected for research purposes. If one objective was mastered before the other, instruction continued only on the objective that had not yet been mastered until mastery was achieved.

Procedure

Baseline Screening Sessions

Prior to beginning instruction, baseline-screening sessions were conducted for all objectives taught during the experiment. These screening sessions were conducted to identify objectives that were not already in the participants’ academic repertoires. Participants were given five opportunities to respond to each objective to determine whether they could respond correctly as a listener and as a speaker. If participants responded with 20% accuracy or below (i.e., 1/5 correct or less), the objective was considered novel. A correct response consisted of the participant emitting the correct response within 3 s, or within an amount of time that was considered appropriate for the expected response. For example, if the objective was addition, the participant was afforded a period of up to 10 s to respond, as the response required for addition requires more time than say a tact response for a sight word program. These criteria were established in advance and were determined by the experimenters’ discretion after consideration of preschoolers’ typical response times for objectives similar to those found in the present study. An incorrect response consisted of the participant emitting a non-target response or not emitting a response at all.

Standard Learn Units (SLUs)

The SLU presentation method of instruction consisted of the experimenter delivering a target discriminative stimulus (SD) in the form of a vocal instruction. If the objective also required stimuli, the experimenter delivered the vocal instruction simultaneously while presenting the stimuli. For example, the antecedent for a sequencing numbers program included the vocal instruction “Put these numbers in order” while simultaneously presenting the student with three different index cards with numbers on them. The student then responded, and the experimenter provided a consequence for that response. A correct response received reinforcement in the form of vocal praise. For incorrect responses and instances of no responding, a correction procedure was delivered. For responses requiring a simple vocal response, participants were given 3 s to respond. For responses that required considerable more time, more time was given for participants to respond (see the example provided in the previous section). Correction procedures consisted of the experimenter re-delivering the antecedent and providing the correct response for the student. The experimenter then re-delivered the antecedent and the student responded independently; however, no consequence was delivered following the independent response after a correction procedure was provided. Each SLU session block consisted of 20 trials.

Instructional Demonstrations followed by Learn Units (IDLUs)

The presentation of IDLUs was identical to the presentation of SLUs except that prior to the initiation of a given session block, two instructional demonstrations were provided to the target participant by the experimenter. The experimenter delivered two antecedent models of the correct response before requiring the participant to complete 20 subsequent learn unit trials for the given objective (i.e., a target SD consisting of a vocal instruction, the simultaneous presentation of any relevant stimuli, and a model showing the participant the correct target response. The experimenter delivered the model two times before the participant received the opportunity to respond). Participants simply observed the models and were not given the opportunity to respond following the models. See Table 3 for examples.

Results

The results of the screening measure in Phase 1 indicated that all participants had the VBD cusp of naming within their repertoires, as evidenced by their ability to respond as both a listener and a speaker to novel 2-D non-contrived stimuli following the naming experience procedure. Participants required a range of 1-5 training sessions and 5-25 single exposures to respond to mastery criterion (see Table 1). For each participant, correct speaker responses were never acquired before correct listener responses for any stimuli.

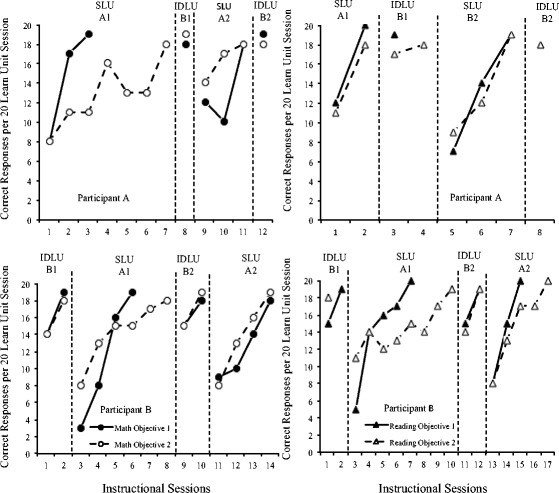

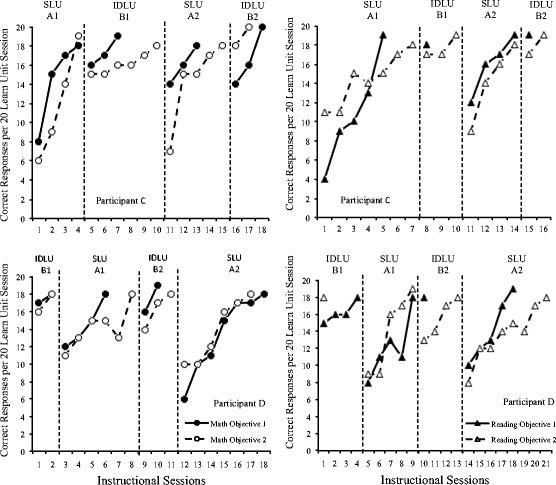

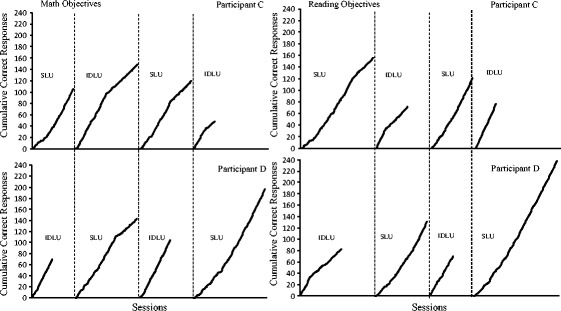

Figures 1 and 2 display the number of learn units required to master mathematics and reading objectives across each condition for Dyads 1 and 2 respectively. The figures show that under the IDLU conditions, participants required fewer trials to master objectives during 20 learn unit sessions. Additionally, the figures show that participants responded with a higher percentage of correct responses during the first trials during the IDLU conditions. Experimenters also graphed the cumulative correct responses under each condition in the exact order in which the responses occurred for each participant, and a comparison of the data path trends for each condition was made. Figures 3 and 4 display the cumulative correct responses for mathematics and reading objectives across each condition for Dyads 1 and 2 respectively. Visual analysis of the cumulative records of correct responding for each participant demonstrated that the data path trends under the IDLU condition were steeper than the data path trends under the SLU condition. These data path trends, with one exception for Participant C’s math objectives (addressed in the discussion), signify that instruction was more efficient under the IDLU condition.

Fig. 1.

Dyad 1’s intervention data showing learn units to mastery of mathematics and reading objectives across SLU and IDLU conditions in phase 2

Fig. 2.

Dyad 2’s intervention data showing learn units to mastery of mathematics and reading objectives across SLU and IDLU conditions in phase 2

Fig. 3.

Dyad 1’s cumulative records of correct responding to master mathematics and reading objectives under the SLU and IDLU conditions in phase 2

Fig. 4.

Dyad 2’s cumulative records of correct responding to master mathematics and reading objectives under the SLU and IDLU conditions in phase 2

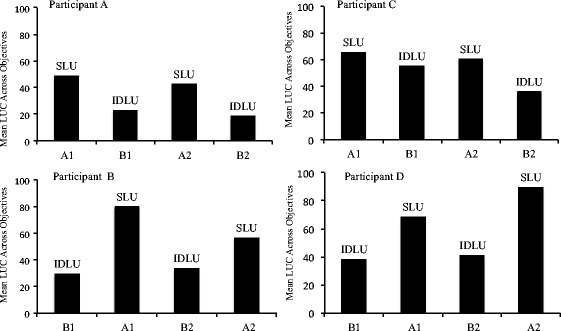

Figure 5 demonstrates that the mean number of learn units-to-criterion for all participants across both mathematics and reading objectives were lower under the IDLU condition than under the SLU condition, signifying that instruction was more efficient when teacher models were used. Participant A’s learn units to criterion data for all four phases (SLU1, IDLU1, SLU2, and IDLU2) were 48.75, 22.75, 42.25, and 18.25 respectively. Participant B’s learn units to criterion data for all four phases (IDLU1, SLU1, IDLU2, and SLU2) were 29.25, 79.75, 33.5, and 56.25 respectively. Participant C’s instruction followed the same sequence as Participant A and his learn units to criterion data were 65.5, 55, 60.25, and 35.75 respectively. Participant D’s instruction followed the same sequence as Participant B and his learn units to criterion were 38, 68.5, 41, and 89.5 respectively.

Fig. 5.

Participants’ mean learn units to criterion across both methods of instruction (i.e., SLU vs. IDLU) for both mathematics and reading objectives in phase 2

An additional measure of efficiency of instruction was conducted through an analysis of the mean number of total 20 learn unit session blocks required for mastery of one objective under each condition. For a mean of every two sessions run under the IDLU condition, one objective was met. However, for a mean of every 4.6 sessions run under the SLU condition, one objective was met. These data demonstrate that when the IDLUs were used with students with the naming capability, objectives were met more than twice as fast, with a ratio of 1:2.3 objectives being met per session block under the SLU condition (1 objective) as compared to the IDLU condition (2.3 objectives).

Participants learned some correct responses simply from observing, i.e., on the first opportunity to respond after having received IDLUs and without having received any consequences at all. Figure 6 demonstrates that all participants responded correctly 0% of the time during the first trials in the SLU conditions. However, during the first trials in the IDLU conditions, Participants A and B responded with 37.5% accuracy, Participant C responded with 62.5% accuracy, and Participant D responded with 50% accuracy. During the first session blocks under the SLU conditions, Participant A responded with 50.6% accuracy, Participant B responded with 33% accuracy, Participant C responded with 44.4% accuracy and Participant D responded with 46.3% accuracy. However, during the first session blocks under the IDLU condition, Participant A responded with 78.6% accuracy, Participant B with 75% accuracy, Participant C with 84% accuracy, and Participant D with 79.4% accuracy.

Fig. 6.

This figure demonstrates the participants’ mean correct responding during first trials and during first session blocks compared across both SLU and IDLU conditions in phase 2

General Discussion

All participants demonstrated the acquisition of tacts for novel 2-D non-contrived stimuli through the naming experience procedure during the pre-screening phase. These results are consistent with research demonstrating that simple exposure is enough for children to contact name-learning opportunities if those children have the naming cusp/capability within their repertoire (Cahill & Greer, 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Childers & Tomasello, 2002; Corwin & Greer, in press). Both the naming experiences and the IDLUs used in the present study incorporated teaching tactics from behavior analysis and encompassed the use of both visual and auditory stimuli. The results of Phase 2 suggest that preschool students with naming benefit greatly from teacher-modeled instruction. These students were able to acquire objectives at a much faster rate under the IDLU condition than under conditions where IDLUs were not provided, as was evidenced by the steep slopes and shorter lengths of their cumulative correct response graphs under these conditions. The mean learn units-to-criterion graph also demonstrated a lower mean number of learn units to meet objectives under the IDLU conditions.

The findings of the present study in combination with the findings of Greer and colleagues (2011) would suggest that an analysis of the learner’s cusps may be most helpful when determining what types of instruction will be beneficial for yielding correct responding from students. More specifically, the presence (analyzed herein) or absence (analyzed by Greer et al., 2011) of the naming cusp appears to influence whether learners can benefit from teacher-modeled instruction. Having information about a learner’s current repertoire may provide valuable information to an educator as to the type of instruction that learner may require in order to be successful in the classroom.

Differences in learning may be a result of missing prerequisite cusps or capabilities, such as naming, which can be instantiated with certain interventions. The procedures in Cahill and Greer (2014) demonstrated that once multiple types of stimuli were conditioned as reinforcers (both auditory and visual), observing responses for those stimuli were then present within the participants’ repertoires. With the presence of those observing responses in their repertoire, participants were able to acquire new targets from instruction that consisted of actions that included both auditory and visual components, not unlike the models that were used in the current study.

Because the participants in the present study acquired the novel tacts during the pre-screening phase, despite the presence of varying, simultaneous, playful actions paired with the names, it is assumed that the auditory and visual stimuli already functioned as conditioned reinforcers for observing responses. These participants likely had a history of reinforcement where both listener and speaker behavior had been brought under the stimulus control of auditory and visual stimuli simultaneously. Furthermore, because these participants were able to respond to multiple components of the stimuli during the naming experiences, the use of IDLUs proved to be an effective teaching method. Therefore, when individuals refer to “different types of learners,” such as auditory or visual learners, it can be argued that what they are really referring to is the individual’s cumulative history of consequences (Coon & Miguel, 2012) that select out one type of observing response over another. This process may lead to either a deficit or strength with one type of repertoire over another. Both the demonstration of naming and learning through IDLUs involve components of observing both auditory and visual stimuli in combination.

Research in verbal behavior has allowed us to analyze development as behavior change and thus to develop teaching tactics from behavior analysis that are derived from the theory of VBD. For students who have difficulty learning from IDLUs, it is logical to argue that perhaps they do not demonstrate certain verbal developmental cusps, such as conditioned reinforcement for observing one or more of the stimuli incorporated into the presentation of the model (i.e., they may not have observing responses for the auditory components and/or the visual components of the model), which impedes their ability to learn from lecture-style lessons.

The data displayed in Fig. 6, yielded a serendipitous finding that was contrary to the experimenters’ expectation. The data displayed in Fig. 6 showed the percentage of correct responses to the first trials of new objectives when no IDLUs were provided as compared to when IDLUs were provided. Based on the majority of the results shown in Figs. 1-5, it would be expected that Participant A would respond with the highest percentage of correct responses following an instructional demonstration, prior to any consequences being given, based on his rate of acquisition of tacts during the pre-screening phase and his longer instructional history due to being the eldest participant. This trend might be expected to continue with Participant B yielding the next highest percentage, followed by Participant C, and lastly Participant D (which follows the participants’ ages in years from oldest to youngest). However, Participants C and D were the participants who responded with the highest percentage of correct responses following an instructional demonstration, before any consequences were delivered. It is important to note that IDLU instruction led participants to come into contact with reinforcement immediately (due to fewer errors as a result from the aid of the models) as compared to SLU instruction, which often led to an error correction procedure. Perhaps it was negatively reinforcing for the two younger participants to respond correctly immediately following the IDLU in order to escape error correction procedures, given their histories with the previous SLU conditions during which they repeatedly contacted error correction.

In Phase 2, an interesting finding occurred in that Participant C required more trials to respond to mastery level criterion for Math Objective 2 during phase B1 of his sequence (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 4) than he did for all other objectives. Participant C’s instructional history with objectives similar to the one in question may have interfered with his responses for that objective, indicating a potential issue with that objective alone. For example, if Participant C had been specifically taught a number sequence incorrectly in the past it may take longer to un-teach an incorrect response and teach a new response than it would to simply teach a correct response from scratch.

These results suggest that when children have the naming capability, teachers should consider providing IDLUs prior to the opportunity to respond in order to accelerate learning. For example, when teaching ‘story-telling for picture sequences’ to a child without naming, a teacher would have to deliver direct contingencies of reinforcement and error correction for each component of the task, i.e., selecting each picture and putting them in the correct order as a listener, and then telling the story that accompanies the pictures as a speaker, e.g., “First you get out the bread, then you spread the butter on the bread, then you eat the sandwich”. However, for a child with naming, an instructional demonstration of the task alone would result in that child emitting the correct response that includes both the listener and speaker components without direct instruction on each component, i.e., the student would be able to both select and arrange the pictures as a listener, and tell the story that accompanies the pictures as a speaker.

A number of limitations occurred that should be taken into consideration when interpreting these findings. One aspect of Phase 2 that could be considered a limitation is that the objectives were not uniform across participants; they were individualized. Because the objectives were individualized, differences between objectives could have influenced the rates at which they were acquired. The experimenters attempted to match objectives on level of difficulty as best as possible. However, objectives can never truly be uniform because children enter into the learning environment with their own individual learning histories for each skill thus affecting their performance on those skills. Although arguments either for or against hetero- or homogenous samples can be made, and a homogenous sample of individuals with the exact same skill deficits would have been ideal, this ideal set of participants is unrealistic. While the variability in the stimulus sets compromises the internal validity of the data, the argument for a need to vary the stimuli based on the learners’ idiosyncratic repertoires persists. When consistency in stimuli sets vs. facilitating a socially significant response was considered, the importance of addressing the latter, given that interest in specific stimuli was secondary to the participants’ performance, resulted in the modifications to the design. In any case, control and intervention procedures were consistent with the method of difference that is the criterion for experimental design (Mills, 1950). Furthermore, the inclusion of a treatment integrity measure would have increased the internal validity of the study.

Another limitation to note is the potential for carry-over effects between Phase 1 and Phase 2. A study conducted by Coon and Miguel (2012) found that recent exposure to an instructional procedure may influence the efficacy of that procedure. Thus, it is possible that the procedures in Phase 1 may have influenced the results of the comparisons in Phase 2. Specifically, exposure to naming experience sessions may have improved the efficacy of the IDLU condition.

Future researchers should consider adding more participants across a wider range of curricular areas. Future researchers should also consider timing the lengths of each session in order to yield a more accurate cost-benefit analysis based on the exact rates at which the participants acquire new objectives under each condition. If future researchers could include data on minute-to-mastery per condition rather than (or in addition to) mean trials-to-criterion, this would make for a stronger argument in terms of the efficiency of one instructional method over another. Building off the research conducted by Greer and colleagues (2011), future researchers should also consider comparing students’ responses when they do not have naming with their responses once naming is induced using the cumulative record of correct responding measure, providing a clearer picture of the changes in students’ responses once naming was induced into their repertoire.

Future researchers could also analyze whether repeatedly presenting IDLUs to students with naming, would be more effective at increasing rates of correct responding than through consequences alone. In other words, after a child emits an incorrect response, would simply providing additional models in lieu of a correction procedure to this child, who has demonstrated the ability to acquire new information in this manner, be more effective? Comparing the number of exemplars needed for acquisition across treatments, and the number of incorrect responses prior to mastery may add additional information that would be valuable to the analyses.

Measuring additional behavior during the naming experiences as well as during the delivery of IDLUs, especially imitative responses or echoics of the names of the stimuli or for tacts included in the model should be considered (Longano & Greer, 2015; Vladescu & Kodak, 2013). This measurement could be used to assess whether the presence of these behaviors could be used as predictors for the effectiveness of the instructional tactic for one learner vs. another. If future researchers wished to replicate these procedures with children with language delays who might have deficits in their echoic repertoires and attending skills, consideration of the role of the echoic would be important. In Vladescu and Kodak’s (2013) study, they measured whether participants echoed the experimenter’s presentations of secondary targets. The authors suggested that generalized imitation, such as echoing, plays an important role in the acquisition of targets in the absence of direct training. Longano and Greer (2015) found increases in echoic responding in conjunction with the emergence of naming and conditioned reinforcement for auditory and visual stimuli. Because frequency of echoic responding may increase with the presence of naming, and naming has an effect on whether a learner may benefit from IDLU instruction, measuring echoic behavior during IDLUs may provide an indication as to whether the IDLU instructional method will be a successful method for teaching new academic objectives to that learner.

The relevant defining characteristic of the current participants was the presence of the naming cusp that allowed them to learn under these conditions, not the fact that they were typically developing. As such, the same procedure should be replicated with students with disabilities who have naming to test whether the same effects emerge. It is hypothesized that the presence of a disability would not impede a child’s learning if all necessary naming cusps were present.

In summary, the findings in the current study suggest that by simply providing two models prior to having a student respond, the likelihood that the student with naming responds correctly on the very first trial following a model is between 30-50% higher and objectives can be met more than twice as fast than if no model is presented. The use of models does not help students unless they have naming (Corwin & Greer, in press; Greer et al., 2011). Thus, the presence of the VBD cusp of naming may be one of the empirically identifiable criteria for inclusion in a general education setting where the use of models is prominent.

The empirical identification of the interaction between instruction and development becomes more promising as a result of findings like these. The applied benefits that result from an understanding of this interaction between instructional procedures and development will result in more effective teaching. The data in the cumulative record graphs presented here are a striking example of clear, orderly data that support the advancement of our understanding of the relation between development as behavioral cusps and ways in which teaching will be more efficient.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. (Please attached in the supplemental material section, an IRB approval document).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Cullinan V. Relational frame theory and Skinner’s verbal behavior: A possible synthesis. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23(1):69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijou SW, Baer DM. Child development, Vol 1: A systematic and empirical theory. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J, Good TL. Teacher behavior and student achievement. In: Wittrock MC, editor. Handbook of research on teaching. 3. New York: Macmillan; 1986. pp. 328–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill CS, Greer RD. Actions vs. words: How we can learn both. Acta de Investigación Psicológica. 2014;4(3):1717–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Carnerero JJ, Pérez-González LA. Induction of naming after observing visual stimuli and their names in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(10):2514–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers JB, Tomasello M. Two-year-olds learn novel nouns, verbs, and conventional actions from massed or distributed exposures. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(6):967–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon JT, Miguel CF. The role of increased exposure to transfer-of-stimulus control procedures on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:657–666. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin, A., & Greer, R. D. (in press). Effect of the establishment of naming on learning from teacher demonstrations by children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis.

- Gewirtz JL, Baer DM. Deprivation and satiation of social reinforcers as drive conditions. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1958;57(2):165–172. doi: 10.1037/h0042880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilic L, Greer RD. Establishing naming in typically developing two-year-old children as a function of multiple exemplar speaker and listener experiences. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27(1):157–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03393099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer, R. D. (2002). Designing teaching strategies: An applied behavior analysis systems approach. Academic Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer RD, Corwin A, Buttigieg S. The effects of the verbal developmental capability of naming on how children can be taught. Acta de Investigacion Psicologia. 2011;1(1):23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, D., & Du, L. (2015). Identification and establishment of reinforcers that make the development of complex social language possible. International Journal of Behavior Analysis & Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(1), 13-34.

- Greer RD, Han HSA. Establishment of conditioned reinforcement for visual observing and the emergence of generalized visual-identity matching. Behavioral Development Bulletin. 2015;20(2):227–252. [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Keohane DD. The evolution of verbal behavior in children. Behavioral Development Bulletin. 2005;12(1):31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Longano J. A rose by naming: How we may learn how to do it. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2010;26(1):73–106. doi: 10.1007/BF03393085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Pistoljevic N, Cahill C, Du L. Effects of conditioning voices as reinforcers for listener responses on rate of learning, awareness, and preferences for listening to stories in preschoolers with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27(1):103–124. doi: 10.1007/BF03393095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Ross DE. Verbal behavior analysis: Inducing and expanding new verbal capabilities in children with language delays. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Speckman J. The integration of speaker and listener responses: A theory of verbal development. The Psychological Record. 2009;59(3):449–488. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. Springer Science & Business Media. 2001. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65(1):185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C. H. (2005). Single-case designs for educational research. Prentice Hall.

- Kirschner PA, Sweller J, Clark RE. Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of the constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist. 2006;41(2):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kobari-Wright VV, Miguel CF. The effects of listener training on the emergence of categorization and speaker behavior in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47(2):431–436. doi: 10.1002/jaba.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longano JM, Greer RD. Is the source of reinforcement for naming multiple conditioned reinforcers for observing responses? The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2015;31(1):96–117. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0022-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JS. A system of logic. In: Wagel E, editor. John Stuart Mill's philosophy of scientific method. New York: Harper; 1950. pp. 20–105. [Google Scholar]

- Novak G, Pelaez M. Child and adolescent development: A behavioral systems approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Delgado JA, Greer RD, Speckman J. Effects of conditioning reinforcement for print stimuli on match-to-sample responding in preschoolers. The Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;3(2-3):60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales-Ruiz J, Baer DM. Behavioral cusps: A developmental and pragmatic concept for behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(3):533–544. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. The technology of teaching (the century psychology series) New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Vladescu JC, Kodak TM. Increasing instructional efficiency by presenting additional stimuli in learning trials for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:805–816. doi: 10.1002/jaba.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery TD, Schuster JW, Collins BC. Effects on future learning of presenting non-target stimuli in antecedent and consequent conditions. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2000;10:77–94. [Google Scholar]