Abstract

Introduction

Rotavirus gastroenteritis is the leading cause of severe diarrhoea among young children < 5 years old. Previous cost-effectiveness analyses on rotavirus (RV) vaccination in Thailand have generated conflicting results. The aim of this current study is to evaluate the economic impact of introducing RV vaccination in Thailand, using updated Thai epidemiological and cost data.

Methods

Both cost-utility analysis (CUA) and budget impact analysis (BIA) of human rotavirus vaccine (HRV) under a universal mass vaccination (UMV) programme were conducted. A published static, deterministic, cross-sectional population model was adapted to assess costs and health outcomes associated with RV vaccination among Thai children < 5 years old during 1 year for CUA and over a 5-year period (2019–2023) for BIA. Data identified through literature review were incorporated into the model after consultation with local experts. Base case CUA was conducted from a societal perspective with quality-adjusted life year (QALY) discounted at 3% annually. Scenario analyses as well as one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the base case CUA results. Costs were updated to 2017.

Results

At 99% coverage, HRV vaccination would substantially reduce RV-related disease burden. With an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of Thai baht (THB) 49,923/QALY gained, HRV vaccination versus no vaccination was cost-effective when assessed against a local threshold of THB 160,000/QALY gained. Scenario and sensitivity analyses confirmed the cost-effectiveness with all resultant ICERs falling below the willingness-to-pay threshold. HRV use in the UMV programme was estimated to result in a net expenditure of about THB 255–281 million to the Thai government in the 5th year of the programme, depending on vaccine uptake.

Conclusion

HRV vaccination is estimated to be cost-effective in Thailand. The budget impact following inclusion of HRV into the UMV programme is expected to be partially offset by substantial reductions in RV-related disease costs.

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA

GSK Study Identifier

HO-17-18213

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40121-019-0246-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Budget impact, Cost-effectiveness, Cost-utility analysis, Human rotavirus vaccine, Rotavirus, Thailand, Universal mass vaccination

Key Points

| Why carry out this study? |

|

• Rotavirus infection is the major cause of rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE), resulting in acute diarrhoea in young children, and is associated with significant health and cost burden in Thailand. • Two vaccines preventing rotavirus, the human rotavirus vaccine (HRV) and the human-bovine reassortant rotavirus vaccine (HBRV) are licensed worldwide and their introduction as universal mass vaccination (UMV) is recommended by the World Health Organization. • The current study aims to evaluate the epidemiological and economic consequences of introducing HRV as part of a UMV programme in Thailand. |

| What was learned from the study? |

|

• The introduction of HRV as part of a UMV programme is expected to be a cost-effective use of healthcare resources in Thailand, when compared to no vaccination. • The introduction of HRV would result in greater costs than no vaccination but would prevent more RVGE-related hospitalisations and deaths. This would significantly improve the quality of life of Thai children, as well as reducing the burden of treatment costs and caregivers’ productivity losses. |

Introduction

Rotavirus (RV) infection is the major cause of gastroenteritis worldwide and results in acute diarrhoea in young children [1]. The virus is transmitted by faecal-oral route and contaminated surfaces and hands [2]. The symptoms of rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) range from vomiting and diarrhoea to fatal dehydration. In Asia, RV is associated with substantial hospitalisations and deaths among children < 5 years old [3]. In Thailand, RVGE is the major cause of acute gastroenteritis, accounting for 28–50% of children admitted to hospital [4]. The estimated RVGE hospitalisation incidence rate among children < 5 years old is 11.3 cases per 1000 children per year and the RVGE-related death rate is 2.2 per 100,000 children per year [3, 5].

To reduce the burden of RVGE, oral vaccines have been developed and the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends their inclusion in all national immunisation programmes [6]. Two internationally available RV vaccines, the human rotavirus vaccine (HRV; Rotarix, GSK) and human-bovine reassortant rotavirus vaccine (HBRV; RotaTeq, Merck & Co. Inc.), have been licensed in Thailand since 2005 and 2008, respectively [7, 8]. HRV is a vaccine based on a single attenuated G1P [8] human rotavirus strain that aims to mimic the protection conferred by natural infection. It is constructed to provide genotype-specific and heterotypic protection against common rotavirus A (RVA) genotypes [9]. HBRV has been developed by introducing human RVA genotype genes (G1-4 and P [8]) into a bovine RVA parent strain to generate five different reassortant strains [10]. The WHO recommends HRV to be administered orally in a two-dose schedule concomitant with the first and second dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccination and HBRV orally in a three-dose schedule together with the three first doses of DTP vaccination, with always at least 4 weeks between the doses [6].

Both vaccines have demonstrated comparable effectiveness against homotypic and heterotypic circulating RV strains in high-, middle- and low-income countries [11–16]. They also have proved to be well tolerated and have demonstrated a similar overall safety profile [17, 18]. Nevertheless, as demonstrated in the US and Mexico, it should be noted that HRV is likely to achieve better completion rates and higher compliance than HBRV because of the difference in their dosing schedules (i.e., two-dose HRV versus three-dose HBRV) [19–22].

The cost-effectiveness of RV vaccination versus no vaccination has been assessed in three previous studies in Thailand, with conflicting results [23–26]. Muangchana et al. showed that vaccination (two or three dose) may not be cost-effective, while Chotivitayatarakorn et al. and Tharmaphornpilas et al. both determined that the two-dose RV vaccination could be cost-effective in Thailand [23–25]. The differences in outcomes were likely due to different model inputs and assumptions incorporated in each study; for instance, the RVGE mortality and incidence, and the vaccine effectiveness used in Muangchana et al., were lower than those used in Chotivitayatarakorn et al. [23, 24].

Given the substantial disease burden as well as conflicting results on the economic value in the previous studies, the objective of this analysis is to evaluate the epidemiological and economic consequences of HRV as part of a universal mass vaccination (UMV) programme in Thailand using relevant and, if available, more recent local data than the previous studies. The choice of data and assumptions was validated with local experts to reflect the current situation in Thailand. This evidence will support government decision-making on the implementation of RV vaccination at national level.

Methods

The methodology used was in line with the Thai health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines [27], together with the model inputs and assumptions, consulted on and validated by local experts.

Modelling Approach

Cost-Utility Analysis

A previously published cost-utility model was adapted to estimate the difference in costs and health outcomes if HRV was to be used as part of a UMV programme versus no vaccination in Thailand [28–30].

The cost-utility model used was a static, deterministic, cross-sectional population model built in Microsoft Excel, consisting of two arms—no vaccination versus RV vaccination with two doses of HRV administered to the individuals in their first year of life—including the following events of interest: (1) RVGE requiring homecare (homecare-RVGE), (2) RVGE requiring outpatient visit (outpatient-RVGE), (3) RVGE requiring hospitalisation (inpatient-RVGE) and (4) RVGE-related death. Given the limited data, to map these events to the data reported in the literature, mild RVGE was considered equivalent to homecare-RVGE, moderate RVGE equivalent to outpatient-RVGE and severe RVGE equivalent to inpatient-RVGE.

A cross-sectional analysis over a 1-year period, during which the vaccination programme was in steady state, was conducted for children aged < 5 years, split into the following age groups: 0 to < 1 years old; 1 to < 2 years old; 2 to < 3 years old; 3 to < 4 years old; 4 to < 5 years old. Based on previous models built for this disease, it was assumed that no further infections would occur after 5 years of age [31, 32]. Adverse events due to the vaccine such as intussusception (IS) were not included in the model as HRV is not commonly associated with adverse events [31, 33–35]. In some settings, post-marketing surveillance has detected a small increased risk of IS shortly after the first dose [36]. However, in recently published surveillance data, the risk of IS after administration of HRV vaccine was not higher than the background risk of IS [37]. In addition, a recent systematic literature review on the economic evaluations of RV vaccines found that only 5% of the reviewed studies incorporated the incidence of vaccine-related adverse event and its cost into their analyses [38]. Given the limited IS risk associated with RV vaccine and the consequent trend in its economic evaluations, the current approach of excluding adverse events such as IS was deemed appropriate.

The primary outcome reported for the cost-utility analysis (CUA) was a discounted incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) comparing RV vaccination with HRV versus no vaccination. In the base case analysis, the results were reported per capita (children < 5 years old) from (1) a societal perspective (base case perspective), (2) a societal perspective excluding caregivers’ productivity loss and (3) a healthcare perspective, where only direct medical costs were considered.

A willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of 1.2 times the gross national income per capita [160,000 Thai baht (THB) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained] was used to assess the cost-effectiveness of HRV vaccination compared with no vaccination [39].

Budget Impact Analysis

As recommended in the Thai HTA guidelines, a budget impact analysis (BIA) was performed in conjunction with the CUA [40]. The BIA estimated the budgetary impact of introducing HRV vaccination in Thailand for 5 years from 2019 to 2023. The change in net costs per year and the accumulated net costs across the whole period were reported from a government perspective, i.e. including only direct medical costs and yet excluding those associated with homecare-RVGE.

A budget impact > THB 200 million per year would refer to a “high” budget impact intervention [41]. In contrast, a budget impact ≤ THB 200 million per year would be considered “low” budget impact; hence, the inclusion of HRV in the national immunisation programme (NIP) would be considered favourable for the government.

Model Inputs

A structured literature review was conducted to identify recent and relevant local data. Where local data were unavailable, data from a neighbouring country, meta-analysis or systematic literature review were obtained. Input data used in the model are presented in Table 1. For the BIA, the same model inputs used in the CUA were used but two additional inputs were incorporated: (1) changes in birth rates and (2) all-cause mortality.

Table 1.

Input data used in the base case cost-utility analysis and budget impact analysis

| Baseline estimates | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 years old | 1–2 years old | 2–3 years old | 3–4 years old | 4–5 years old | ||

| Epidemiological data | ||||||

| Cohort size | 620,066 | 655,161 | 683,536 | 725,867 | 742,948 | Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand [42] |

| RVGE incidence and mortality (annual probability) | ||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 0.010841 | 0.012323 | 0.006181 | 0.004191 | 0.003095 | Estimated from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [26] |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 0.032461 | 0.036902 | 0.018428 | 0.012521 | 0.009257 | |

| Inpatient-RVGE | 0.010791 | 0.031736 | 0.017053 | 0.012323 | 0.006777 | |

| RVGE-related death < 5 years old | 0.000024 | 0.000070 | 0.000037 | 0.000027 | 0.000015 | WHO, Child rotavirus deaths by country [44] |

| All-cause mortality | 0.006354 | 0.000540 | 0.000540 | 0.000540 | 0.000540 | Ministry of Public Health Statistics [45] |

| Annual rate of change in natality (%) | − 2.85 | Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand [42] | ||||

| Baseline estimates | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||

| Epidemiological data | ||||||

| Birth cohort used in the BIM | 696,480 | 685,829 | 650,332 | 627,185 | 620,066 | Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand [42] |

| Baseline estimates | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 years old | 1–2 years old | 2–3 years old | 3–4 years old | 4–5 years old | ||

| Vaccine effectiveness (%) | ||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 70.0 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | Li et al. [46] |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 70.0 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | |

| Inpatient-RVGE | 85.7 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 71.8 | |

| RVGE-related death | 98.4 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 97.1 | |

| RVGE duration (days) | ||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 3 | Riera-Montes et al. [54] | ||||

| Outpatient-RVGE | 3 | |||||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 4 | |||||

| Costs, THB (USD)a | ||||||

| Vaccination cost, per course | 790b (23) | HRV manufacturer; Tharmaphornpilas et al. [25] | ||||

| Direct medical cost, per event | ||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 174 (5) | Muangchana et al. [24] | ||||

| Outpatient-RVGE | 759 (22) | |||||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 4153 (122) | |||||

| RVGE-related death | 0 (0) | |||||

| Baseline estimates | Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | Meal | Caregiver productivity loss | ||

| Costs, THB (USD)a | ||||

| Direct non-medical cost, per event | ||||

| RV vaccination | 0 (0)c | 0 (0)c | 0 (0)c | Assumption |

| Homecare-RVGE | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 1043 (31) | Saokaew et al. [61]; Riewpaiboon et al. [60]; Riewpaiboon et al. [58]; Riera-Montes et al. [54] |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 93 (3) | 41 (1) | 1043 (31) | |

| Inpatient-RVGE | 112 (3) | 52 (2) | 1391 (41) | |

| RVGE-related death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Assumption |

| Baseline estimates | Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 years old | 1–2 years old | 2–3 years old | 3–4 years old | 4–5 years old | ||

| LY, QALY and utility | ||||||

| Baseline QALY | 66.3 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 | Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand [42]; WHO, Global Health Estimates [62]; WHO, Methods for life expectancy and healthy life expectancy [63]; WHO, Global Health Observatory Data Repository [64] |

| Baseline LY | 74.9 | 74.7 | 74.7 | 74.7 | 74.7 | |

| Utility weights | ||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 0.685 | Rochanathimoke et al. [65] | ||||

| Outpatient-RVGE | 0.660 | |||||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 0.591 | |||||

BIM budget impact model, DTP diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, EPI Expanded Program on Immunization, HE health economics, HTA health technology assessment, HRV human rotavirus vaccine, LY life-year, QALY quality-adjusted life year, RV rotavirus, RVGE rotavirus gastroenteritis, THB Thai baht; USD US dollar, WHO World Health Organization

aCosts inflated to year 2017, using relevant Consumer Price Indexes as suggested by the Thai HTA guidelines [55–58] and the annual 2017 exchange rate (THB 33.9385/USD) was applied [59]

bAccounting for vaccine acquisition cost of THB 395 per dose inclusive of every cost to the customer’s end (including Value Added Tax 7% and distribution cost 2.5%); the price used in the study was only an indicative price for this HE study, and it has no reference to the actual price being quoted for tender in Thailand

cAssumed to be zero as RV vaccination occurs along with DTP vaccination

dAssumed to be zero because of treatment being homecare

Epidemiological Data

The number of individuals in each age cohort used in the model was based on values reported in the Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand for 2017 [42] (Table 1).

Annual probabilities of RVGE incidence were estimated for each health state in the different age cohorts (Table 1). The estimates were derived from a cost-utility study on HRV, conducted as a part of an observational study in two provinces of Thailand [25, 26]. The reported incidence of inpatient-RVGE between 0 and 24 months was re-calculated to fit into the single-year age groups allowed in the model, and the reported incidence rates were converted to annual probabilities for use in the model [5, 43].

RVGE-related mortality was based on WHO data on childhood RV deaths in Thailand between 2000 and 2013 [44] (Table 1). Two previous publications on the cost-utility analyses of RV vaccination in Thailand reported RVGE-related mortality rates of 0.56 per 100,000 children in Muangchana et al. [24] versus 0.1 per 1000 live births in Chotivitayatarakorn et al. [23]. In view of this large variation in the local mortality data, the annual RVGE mortality of 3.4 [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.1–3.7] per 100,000 children < 5 years old, reported by the WHO [44], was estimated to be the most robust and thus used to calculate the total number of events in all age groups considered in the model. It is of note that this WHO estimate lies between the mortality rates used in Muangchana et al. and Chotivitayatarakorn et al. [23, 24]. As no age-stratified RVGE mortality data were available, age-stratified RVGE-related probabilities of death in the no-vaccination arm were estimated based on the proportion of inpatient-RVGE cases in the no-vaccination arm of each age group [26] (Table 1).

In addition to RVGE-related mortality, the budget impact model (BIM) also accounted for all-cause mortality across age groups in line with Thai HTA guidelines [40]. The figures were based on the Ministry of Public Health Statistics from 2016, the most recent data available in Thailand at the time of the analysis [45] (Table 1).

The natality rate was used in the BIM to calculate the number of new individuals to be included in each year [40]. The birth cohorts in Thailand between 2013 and 2017 were used to calculate an average rate of change in natality and thus to project the birth cohort size for the years 2019–2023 [42]. These projected birth cohorts entered the model for the 0–1 years old age group and progressed through the age groups, according to the year of the model (Table 1).

Vaccine Effectiveness

Although vaccine effectiveness is preferred to vaccine efficacy (VE) for the measurement of health outcomes according to Thai HTA guidelines, VE data were used in the base case as proxies for vaccine effectiveness because of limited effectiveness data available in Thailand. While vaccine effectiveness data were available from one observational study in Thailand, the only relevant reported data was the effectiveness against RVGE hospitalisations [25]. Hence, these data were not considered sufficient to use for the base case but were however explored in a scenario analysis.

Since no RV efficacy clinical trials were done for Thailand, the base case VE was derived from a clinical trial in China [46], both countries having comparable demographics and RVGE mortality [44]. Due to the limited end points reported, vaccine effectiveness against both homecare-RVGE and outpatient-RVGE were assumed to be equivalent to the reported VE against RVGE of any severity. VE against inpatient-RVGE was used as a proxy for the vaccine effectiveness against inpatient-RVGE. No RVGE-related deaths were reported in the trial and as such vaccine effectiveness against RVGE-related deaths could not be directly estimated from the trial. Hence, the upper bound of the 95% CI for VE against inpatient-RVGE was used to estimate the vaccine effectiveness against RVGE-related death. VE was assumed to be the same irrespective of the distribution of the RV genotypes (Table 1).

The VEs during the first and second season were used to estimate the vaccine effectiveness for the 0–1- and 1–2 years old age groups, respectively. Based on published studies, vaccine effectiveness was assumed to remain constant across all age groups > 1 years old [47–49]. These studies noted that VE was sustained up to the third year of life [49] and did not appear to decline with age in high socio-economic settings with a very low child mortality [47–49]. For Thailand, an upper-middle-income-level country with a low child mortality rate, the vaccine effectiveness was assumed to be sustained during years 2–5 post-vaccination [50–52]. Furthermore, it was expected that any uncertainty about vaccine effectiveness from year 3 onwards would have a minimal impact on the results due to the relatively low levels of RVGE incidence compared with the earlier years (Table 1).

Vaccination Coverage

The vaccination coverage was derived from the WHO Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) fact sheet [53]. The 2016 figure of 99% for the third dose of DTP vaccine coverage was used to represent the proportion of the individuals in the HRV arm that would be vaccinated with a full course of HRV. In the base case BIA, the coverage was assumed to be sustained throughout the whole 2019–2023 period.

Duration of RVGE Clinical Events

The duration of each RVGE-associated event in the model was taken from Riera-Montes et al., a global systematic review and meta-analysis of RV disease severity in children (Table 1) [54]. As data on homecare-RVGE were not reported, it was assumed that they would be the same as duration for outpatient-RVGE.

Costs

Direct medical costs and direct non-medical costs, including transportation and meal costs, and productivity loss of caregivers, were considered for the CUA from the base case societal perspective. In the BIA, only direct medical costs associated with outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE were considered. Costs were inflated to year 2017, using relevant consumer price indexes as suggested by the Thai HTA guideline [55–58]. An annual 2017 exchange rate (THB 33.9385/USD) was applied [59] and costs were rounded to the nearest unit.

The cost of vaccination used in the model was THB 790 [US dollars (USD) 23] per course [THB 395 (USD 12) per dose], including the vaccine acquisition cost with Value Added Tax (7%) and distribution cost (2.5%) (HRV manufacturer) [25]. No vaccine administration cost was considered since healthcare professionals in Thailand are paid on a salary basis.

The base case estimates for direct medical costs for each event were based on figures from Muangchana et al., an economic study on RV vaccination previously conducted in Thailand [24] (Table 1). This source was deemed more appropriate for the base case analysis than a more recent publication by Tharmaphornpilas et al. [26] as the costs estimated by Muangchana et al. [24] (1) are nationwide estimates, while data in the more recent source were derived from one province only and (2) appear to be derived from government hospitals in Thailand. To fit the Muangchana et al. data into the model of the current analysis, it was assumed that (1) homecare-RVGE was equivalent to ‘treatment cost: drugstore’ from the published source; (2) outpatient-RVGE to ‘treatment cost before/after hospital care’ and ‘direct medical cost per outpatient case’; (3) inpatient-RVGE to ‘treatment cost before/after hospital care’ and ‘direct medical cost per inpatient case’. For RVGE-related deaths, no costs were applied, assuming that they were already considered in the other states of RVGE. Of note, the cost data from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [26] were explored in a scenario analysis.

Transportation and meal costs (direct non-medical costs) were based on Riewpaiboon et al., a study undertaken to generate a set of standard costs for use in health economic evaluations in Thailand [60]. Although highly conservative, they were deemed the most appropriate estimates for the current analysis given the variations in the country. One visit per event was assumed. In line with the HTA guidelines, which suggest using a human capital approach to value the caregivers’ time loss, independent of the individual’s characteristics, income or type of time (e.g., paid versus unpaid work), caregivers’ productivity losses were based on the cost of daily productivity loss from Saokaew et al. [61]. The cost data were averaged by age groups (15–29 and 30–39 years old), representing the age of a parent likely to have a child eligible for RV vaccination and then multiplied by the duration of each clinical event from Riera-Montes et al. [54] to obtain the total cost of caregivers’ productivity loss for each event (Table 1). Again, no direct non-medical costs for RVGE-related deaths were assumed for the reason detailed above.

Life-Year and QALY Loss

Health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) was used to calculate baseline QALYs and then calculate QALY losses for premature deaths due to RVGE, using sources from the Official Statistics Registration Systems in Thailand for 2017 and WHO [42, 62–64]. HALE was considered the most appropriate estimate given the limited baseline QALY data available for Thailand and the assumption that the use of life-years (LYs) to represent baseline QALYs would overestimate QALY losses due to RVGE-related death. Baseline LYs were calculated based on the same data source [42, 62–64].

Utility weights for RV events other than death were derived from Rochanathimoke et al., which provided the most updated Thai-specific utility data [65]. Utility weight for mild RVGE was not available in Rochanathimoke et al.; hence, the non-RVGE utility for mild-severity patients was used for homecare-RVGE (considered equivalent to mild RVGE) since there were no significant differences between RVGE and non-RVGE utility within the other severity levels of the study. The difference between the reported utility weight and 1 (representing perfect health) was applied to the relevant number of days to calculate the QALY loss from these events [54] (Table 1).

Discount Rate

A discount rate of 3% was used for health outcomes only in the CUA [66]. No discounting was applied to the costs in the CUA as the costs in this cross-sectional analysis were considered only over a 1-year period. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using a range of discount rates between 0% and 6% for health outcomes [67]. In line with the Thai HTA guidelines and standard practice for BIMs, no discounting was applied in the BIA [40].

Scenario and Sensitivity Analyses

Cost-Utility Analysis

Scenario analysis on the model inputs for vaccine effectiveness and direct medical costs was conducted as Thailand-specific data were available from alternative sources to those selected in the base case. The rationale for choosing the base case inputs over these alternatives has been described earlier in the “Vaccine effectiveness” and “Costs” sections.

In the first scenario, the vaccine effectiveness of 88.0% for inpatient-RVGE, reported in an observational study in Thailand from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [25], was explored. Vaccine effectiveness for homecare-RVGE and outpatient-RVGE, not reported in the observational study, remained the same as in the base case. As done in the base case, the vaccine effectiveness of 94.0% was applied for RVGE-related death, derived as the upper bound of the 95% CI for vaccine effectiveness for inpatient-RVGE. In the second scenario analysis, the direct medical costs from Tharmaphornpilas et al. were used [26], where the costs for homecare-RVGE, outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE were estimated to be THB 89 (USD 3), THB 488 (USD 14) and THB 6711 (USD 198), respectively.

To assess the robustness of the CUA, a one-way sensitivity analysis and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) were conducted. In the one-way sensitivity analysis, the key drivers of the CUA were identified by varying the input data by ± 15% or using the upper/lower bounds reported from the data sources, as presented in Table 2 [68]. In the PSA, a 15% variation from the mean value was used when the CI or standard deviation (SD) was not available for the input, with the distribution used depending on the type of variable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Values used in one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses

| Variable | Base case (mean value) | One-way sensitivity analysis | Probabilistic sensitivity analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Distribution | SD/range | Notes | |||

| Costs (THB) | |||||||

| Vaccination costs per course | 790 | 672 | 909 | – | – | Not included in the PSA | |

| Direct medical costs | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 174 | 148 | 200 | Gamma | 26.07 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 759 | 645 | 873 | Gamma | 113.83 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 4153 | 3530 | 4776 | Gamma | 622.94 | ||

| Direct non-medical costs | |||||||

| Transportation costs | |||||||

| Outpatient-RVGE | 93 | 56 | 148 | Gamma | 4.39 | SD based on reported standard error from Riewpaiboon et al. [60] | |

| Inpatient-RVGE | 112 | 75 | 148 | Gamma | 8.70 | ||

| Meal costs | |||||||

| Outpatient-RVGE | 41 | 18 | 69 | Gamma | 2.23 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 52 | 35 | 69 | Gamma | 4.40 | ||

| Daily productivity loss of a caregiver | 348 | 296 | 400 | Gamma | 52.15 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| Duration of RVGE (days) | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 3 | 2 | 5 | Binomial | N/A | Distributions approximated based on a binomial distribution with 100,000 trials, with a probability that leads to the expected value to be the base case value | |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 3 | 2 | 5 | Binomial | |||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 4 | 4 | 5 | Binomial | |||

| Probability of RVGE incidence (%) | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | |||||||

| 0–1 years old | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | Beta | 0.16 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| 1–2 years old | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | Beta | 0.18 | ||

| 2–3 years old | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | Beta | 0.09 | ||

| 3–4 years old | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | Beta | 0.06 | ||

| 4–5 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | Beta | 0.05 | ||

| Outpatient-RVGE | |||||||

| 0–1 years old | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.7 | Beta | 0.49 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| 1–2 years old | 3.7 | 3.1 | 4.2 | Beta | 0.55 | ||

| 2–3 years old | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 | Beta | 0.28 | ||

| 3–4 years old | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | Beta | 0.19 | ||

| 4–5 years old | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | Beta | 0.14 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | |||||||

| 0–1 years old | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | Beta | 0.16 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| 1–2 years old | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.6 | Beta | 0.48 | ||

| 2–3 years old | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | Beta | 0.26 | ||

| 3–4 years old | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | Beta | 0.18 | ||

| 4–5 years old | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | Beta | 0.10 | ||

| Under-5 years old RVGE-related death | 116.5a | 106.3 | 126.8 | Normal | 0.15 | Mean and SD calculated from the reported lower limit and upper limit of 3.1 and 3.7 per 100,000 children < 5 years old as 95% confidence interval | |

| Utility | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 0.685 | 0.582 | 0.788 | Beta | 0.015 | Based on the reported SD in Rochanathimoke et al. [65] | |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 0.660 | 0.561 | 0.759 | Beta | 0.106 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 0.591 | 0.502 | 0.680 | Beta | 0.124 | ||

| Health-adjusted life expectancy at birth (years) | 66.3 | 56.4 | 76.2 | Normal | 9.95 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| Vaccination coverage (%) | 99.0 | 84.0 | 100.0 | – | – | Not included in the PSA | |

| Health outcomes discount rate (%) | 3.0 | 0.0b | 6.0b | – | – | Not included in the PSA | |

| Vaccine effectiveness | |||||||

| Vaccine effectiveness in 0–1 years old (%) | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 70.0 | 53.5 | 81.3 | Beta | 53.5–81.3 | Based on 95% confidence interval reported by Li et al. [46] | |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 70.0 | 53.5 | 81.3 | Beta | 53.5–81.3 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 85.7 | 37.9 | 98.4 | Beta | 37.9–98.4 | ||

| RVGE-related death | 98.4 | 83.6 | 100.0 | Beta | 0.85 | Distribution parameters based on the mean as the base case and the upper bound being bounded by 100%, with the resulting estimated SD as shown | |

| Decrease in vaccine effectiveness from 0–1 to 1–2 years old (%) | |||||||

| Homecare-RVGE | 34.9 | 29.6 | 40.1 | Beta | 5.23 | SD assumed to be 15% of the mean | |

| Outpatient-RVGE | 34.9 | 29.6 | 40.1 | Beta | 5.23 | ||

| Inpatient-RVGE | 16.2 | 13.8 | 18.7 | Beta | 2.43 | ||

| RVGE-related death | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | Beta | 0.20 | ||

HTA health technology assessment, N/A not applicable, PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, RVGE rotavirus gastroenteritis

SD standard deviation, THB Thai baht

aMortality of 3.4 per 100,000 children < 5 years old was used to calculate this figure

bDiscount rate varied from 0.0% to 6.0% as recommended by the Thai HTA guidelines [67]

Budget Impact Analysis

Given the uncertainty about the RV vaccination coverage rate to be reached in the first few years of introduction in the NIP, a scenario analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of the vaccination coverage on the budget. In this scenario, the initial vaccination coverage was assumed to be 59.40% during the first year, followed by an exponential increase to 67.49%, 76.69% and 87.13% in the following years (year 2, 3 and 4, respectively) and reaching the base case target coverage level of 99.0% in the last year of the analysis.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Cost-Utility Analysis

Base Case

RV vaccination with HRV resulted in a substantially lower number of RVGE-related events compared with no vaccination, with a 52% reduction in homecare-RVGE and outpatient-RVGE cases, a 73% reduction in inpatient-RVGE cases and a 96% reduction in RVGE-related deaths (Table S1).

In the base case of the CUA, the discounted ICER was estimated at THB 49,923 (USD 1471) per QALY gained from the base case societal perspective. As this ICER fell below the WTP threshold of THB 160,000 per QALY gained [39], it suggested that vaccination with HRV would be a cost-effective use of healthcare resources in Thailand. The other perspectives considered in the base case analysis also produced ICERs below the WTP threshold (Table 3; Table S1).

Table 3.

Results of the cost-utility analysis: base case analysis from different perspectives and scenario analyses

| Results (per capita) | Total costs; THB (USD) | Net QALY loss (discounted) | Difference in total costs; THB (USD) | Difference in net QALY loss | ICER per QALY gained; THB (USD)/QALY gained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | |||||

| Societal perspective (base case perspective) | |||||

| With HRV | 190 (6) | 0.000092 | 51 (2) | − 0.001027 | 49,923 (1471) |

| No vaccination | 138 (4) | 0.001120 | |||

| Societal perspective excluding productivity losses | |||||

| With HRV | 169 (5) | 0.000092 | 82 (2) | − 0.001027 | 80,126 (2361) |

| No vaccination | 87 (3) | 0.001120 | |||

| Healthcare perspective | |||||

| With HRV | 167 (5) | 0.000092 | 86 (3) | − 0.001027 | 83,351 (2456) |

| No vaccination | 82 (2) | 0.001120 | |||

| Scenario analyses (base case societal perspective) | |||||

| Vaccine effectiveness scenario analysis from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [25] | |||||

| With HRV | 177 (5) | 0.000114 | 39 (1) | − 0.001006 | 38,410 (1132) |

| No vaccination | 138 (4) | 0.001120 | |||

| Direct medical costs scenario analysis from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [26] | |||||

| With HRV | 197 (6) | 0.000092 | 26 (1) | − 0.001006 | 25,037 (738) |

| No vaccination | 172 (5) | 0.001120 | |||

HRV human rotavirus vaccine, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, QALY quality-adjusted life year, THB Thai baht, USD US dollar

Scenario and Sensitivity Analyses

The ICERs from the scenario analysis, one-way sensitivity analysis and simulations in the PSA all fell below the WTP threshold, as presented hereafter.

In both scenarios explored, the first one exploring local vaccine effectiveness from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [25] for inpatient-RVGE and the second one using direct medical costs data from Tharmaphornpilas et al. [26], the resulting discounted ICERs were below the WTP threshold of THB 160,000 per QALY gained. With an estimated ICER of THB 38,410 (USD 1132) and THB 25,037 (USD 738), respectively, they were even lower than the base case ICER estimate (Table 3). See also Table S2 in the electronic supplementary material for details.

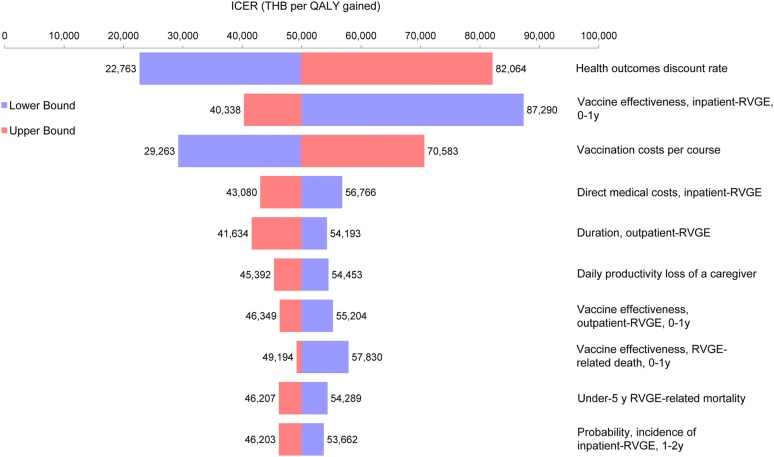

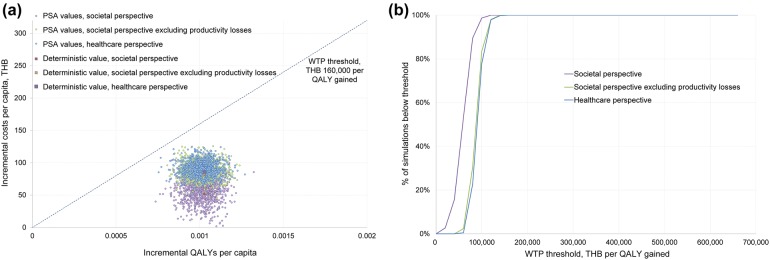

The one-way sensitivity analysis further assessed the reliability of the analysis and provided the inputs having the greatest impact on the CUA results, in order: the health outcomes discount rate, vaccine effectiveness against inpatient-RVGE for the 0–1 years old age group and vaccination costs (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the ICERs always remained below the WTP threshold of THB 160,000 per QALY gained. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve from the PSA showed that, across all three perspectives, 100% of the simulations were below the WTP threshold of THB 160,000 per QALY gained (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Tornado diagram for one-way sensitivity analysis. ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, QALY quality-adjusted life year, RVGE rotavirus gastroenteritis, THB Thai baht, y years old

Fig. 2.

PSA results: a PSA scatter plot; b cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, QALY quality-adjusted life year, THB Thai baht, WTP willingness to pay

Budget Impact Analysis

Base Case

In the base case, the total budget impact of HRV vaccination compared with no vaccination in the first year (2019) was projected to be THB 425,464,109 (USD 12,536,326), falling to THB 254,824,035 (USD 7,508,406) by 2023 (Table 4). Vaccination costs were a significant driver of this figure, while there were projected cost savings of THB 9,990,419 (USD 294,368) and THB 22,252,117 (USD 655,660) across costs for outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE in the first year, respectively (Table S3). The outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE cost savings were projected to increase each year because of the changing levels of RVGE incidence resulting from vaccination, while the vaccination costs were projected to decrease each year because of the decreasing size of the birth cohort. In all years considered, the annual budget impact was > THB 200 million, a threshold denoting an intervention considered to have a ‘high’ budget impact in Thailand [41].

Table 4.

Base case and scenario results of the budget impact analysis

| Year | Vaccination coverage (%) | Costs; THB (USD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No vaccination | With HRV | HRV versus no vaccination Total difference |

HRV versus no vaccination Cumulative difference |

||

| Base case | |||||

| 2019 | 99.00 |

249,809,757 (7,360,660) |

675,273,866 (19,896,986) |

425,464,109 (12,536,326) |

425,464,109 (12,536,326) |

| 2020 | 99.00 |

242,738,973 (7,152,319) |

594,249,334 (17,509,593) |

351,510,361 (10,357,275) |

776,974,470 (22,893,601) |

| 2021 | 99.00 |

235,838,863 (6,949,007) |

544,405,260 (16,040,935) |

308,566,397 (9,091,928) |

1,085,540,867 (31,985,529) |

| 2022 | 99.00 |

229,117,825 (6,750,971) |

505,267,278 (14,887,732) |

276,149,452 (8,136,761) |

1,361,690,319 (40,122,289) |

| 2023 | 99.00 |

222,588,327 (6,558,579) |

477,412,362 (14,066,985) |

254,824,035 (7,508,406) |

1,616,514,354 (47,630,695) |

| Scenario analysis | |||||

| 2019 | 59.40 |

249,809,757 (7,360,660) |

505,088,223 (14,882,456) |

255,278,465 (7,521,796) |

255,278,465 (7,521,796) |

| 2020 | 67.49 |

242,738,973 (7,152,319) |

487,428,060 (14,362,098) |

244,689,087 (7,209,779) |

499,967,552 (14,731,575) |

| 2021 | 76.69 |

235,838,863 (6,949,007) |

486,180,312 (14,325,333) |

250,341,450 (7,376,326) |

750,309,002 (22,107,901) |

| 2022 | 87.13 |

229,117,825 (6,750,971) |

491,280,483 (14,475,610) |

262,162,658 (7,724,639) |

1,012,471,659 (29,832,540) |

| 2023 | 99.00 |

222,588,327 (6,558,579) |

503,900,312 (14,847,454) |

281,311,984 (8,288,875) |

1,293,783,644 (38,121,415) |

HRV human rotavirus vaccine, THB Thai baht, USD US dollar

Scenario Analysis

With 59.40% coverage in the first year of the model (2019), the total budget impact of HRV vaccination compared with no vaccination was projected to be THB 255,278,465 (USD 7,521,796) (Table 4). As vaccine coverage increased each year in this scenario, vaccination costs were projected to increase each year, while costs for outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE were projected to decrease. Nevertheless, total budget impact was projected to marginally increase across 2019–2023. The budget impact in 2019 in this scenario was lower than in the base case because of the lower vaccination costs, but greater by 2023, when the target coverage had been reached; the offset in costs due to reductions in outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE costs was lower, as fewer individuals had been vaccinated in the model. The budget impact for each year was slightly greater than THB 200 million per year, ranging between THB 244,689,087 (USD 7,209,779) in 2020 to THB 281,311,984 (USD 8,288,875) in 2023. See also Table S4 in the electronic supplementary material for details.

Discussion

The model used for the current analysis is a simple model that has recently not only been shown to reach similar conclusions as that of a more advanced model but also to be useful for countries with limited data [29, 30]. The current model is further modified and adapted to a Thai setting, incorporating available data into the model to improve the precision of the modelling (e.g., use of reported age-stratified RVGE incidence rather than assuming a linear decrease of RVGE events as a function of age).

This study demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of implementing an RV vaccination programme targeting children < 1 year old in Thailand. In the base case of the CUA, HRV vaccination results in a discounted ICER of THB 49,923 (USD 1471) per QALY gained from the societal perspective. The ICER predicted in this study suggests HRV to be cost-effective in Thailand, which is in line with the results of Chotivitayatakorn et al. and Tharmaphornpilas et al. along with its study report and most of the cost-utility studies conducted for upper-middle-income countries identified in a recent systematic literature review [23, 25, 26, 38].

The conclusions from the base case CUA remain consistent even when examined via scenario and sensitivity analyses. In all scenarios analysed, the estimated ICERs remain below the WTP threshold of THB 160,000 per QALY gained. The one-way sensitivity analysis shows that the key drivers of the model include: the health outcomes discount rate, vaccine effectiveness against RVGE requiring hospitalisation and vaccination costs. The PSA further emphasises the robustness of the conclusions, with all simulations across the three perspectives falling below the WTP threshold.

The BIA considers direct medical costs relevant for the government across 5 years and shows that introducing HRV vaccination would result in a substantial budget impact. This would be due to the vaccination costs, which would be somewhat offset by reductions in outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE costs. In the base case, the vaccination costs are shown to decrease each year because of the decreasing size of the birth cohort in Thailand, and the savings on outpatient-RVGE and inpatient-RVGE costs were shown to increase each year because of the reduced RVGE incidence as a result of vaccination. While the base case assumes target vaccine coverage of 99% from the first year, in the scenario analysis, vaccine coverage is assumed to start at a lower level in the first year and to increase until the target coverage is reached in the fifth year of the model. The scenario analysis projects the budget impact in the first year of the model to be lower than predicted in the base case of the model. In the base case, the budget impact is predicted to decrease each year. However, the budget impact in the scenario analysis, due to increasing uptake of the vaccine, is expected to rise each year over the 5-year period; the budget impact of HRV is dependent on the vaccine coverage rate. It is important to note that the budget impact is one among many other determinant factors of inclusion in the NIP.

One may consider that target coverage of 99% is not achievable for HRV vaccination. However, use of the second- or third-dose DTP vaccine coverage to estimate the overall RV vaccine coverage is a commonly adopted approach in health economics studies for RV vaccination, as seen in the previous Thai cost-effectiveness study [23]. This approach is based on the WHO recommendation to administer a two-dose HRV vaccine concomitantly with the first and second dose of DTP vaccine [6]. Indeed, a recent observational study conducted in two provinces of Thailand has reported similar coverages between the second dose of DTP vaccine and second dose of HRV vaccine [25]. The use of 99% target coverage also allows the current analysis to undertake a conservative approach by calculating the upper estimate of potential budget impact for Thailand.

The comprehensive scenario and sensitivity analyses conducted ensured that the uncertainty around model inputs was tested and showed the results of the analysis to be robust. However, despite its robustness, this analysis, like any other health economic analyses, has several limitations. Primarily, several assumptions are required given the limited data availability. For example, vaccine efficacy from a clinical trial conducted in China is used as a proxy for vaccine effectiveness in Thailand in the base case; RVGE of ‘any severity’ was assumed to be equivalent to homecare-RVGE and outpatient-RVGE, etc. Another limitation is associated with the utility weights for events other than death—the data source used observed mostly severe cases and the utility measurements were made on the first day of an episode. The utility weights potentially reflected a higher severity level than the severity of the whole episode and hence may have underestimated the utility values of the episodes. Also, due to the static nature of the model, herd immunity cannot be modelled. However, as this analysis is focused on when the vaccination programme is in steady state, with vaccine coverage of 99%, this is not anticipated to significantly impact the results. Nonetheless, the methodology was thoroughly validated by local clinical and health economics experts and cross-checked with the Thai HTA guidelines. For instance, regarding the above example of using vaccine efficacy derived from the clinical trial in China, this was discussed in depth and considered reasonable for both countries having comparable demographics and RVGE mortality.

Conclusion

The introduction of HRV vaccination as part of a UMV programme in Thailand is expected to be cost-effective. While a UMV programme would result in greater costs, fewer RVGE-related deaths and lower RV-associated QALY losses, the analysis showed that such a programme would represent good value for the money compared with the local Thai ICER WTP threshold.

The BIA shows that the introduction of HRV would represent a substantial budget impact, although there would be sustained annual savings on outpatient- and inpatient-RVGE costs. However, the vaccine coverage would influence the increase in vaccination costs and the reduction in outpatient- and inpatient-RVGE costs. As a result, the affordability of HRV would be highly dependent on the vaccine uptake. In addition, the budget impact is only one among other determinant factors to account for the decision of inclusion in the NIP.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Trademark

Rotarix is a trademark of the GSK group of companies. Rotateq is a trademark of Merck & Co. Inc.

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was the funding source and was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis (GSK study identifier: HO-17-18213). GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also took over all costs associated with the development and publication of the present manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical writing, editorial, and other assistance

The authors thank Prof. Somsak Lolekha (Mahidol University, Thailand) and Claire Montante (GSK, Belgium) for their contribution to the study as well as Rebecca Crawford (GSK, Singapore) for her support during the publication development. The authors also thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination on behalf of GSK: Nathalie Arts coordinated manuscript development and editorial support and Sarah Fico provided medical writing support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Wasana Prasitsuebsai is an employee of and holds shares in the GSK group of companies. Gyneth Lourdes Bibera is an employee of and holds shares in the GSK group of companies. Xu-Hao Zhang is an employee of and holds shares in the GSK group of companies. Kyu-Bin Oh is an employee of and holds shares in the GSK group of companies. Christa Lee is an employee of the GSK group of companies. Surasak Saokaew and Kirati Kengkla have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies which evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. To access data for other types of GSK sponsored research, for study documents without patient-level data and for clinical studies not listed, please submit an enquiry via the website.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7998818.

References

- 1.Glass RI, Parashar UD, Bresee JS, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: current prospects and future challenges. Lancet. 2006;368(9532):323–332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennehy PH. Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(10):S103–S105. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200010001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawai K, O’Brien MA, Goveia MG, Mast TC, El Khoury AC. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis and distribution of rotavirus strains in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(7):1244–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittigul L, Swangsri T, Pombubpa K, Howteerakul N, Diraphat P, Hirunpetcharat C. Rotavirus infection in children and adults with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45(4):816–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiraphongsa C, Bresee JS, Pongsuwanna Y, et al. Epidemiology and burden of rotavirus diarrhea in thailand: results of sentinel surveillance. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(Supplement_1):S87–S93. doi: 10.1086/431508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper—January 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;5(8):49–64. http://www.who.int/wer/2013/wer8805.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18 Jul 18.

- 7.Ministry of Public Health—Thailand. Product Review (Rotarix). http://pertento.fda.moph.go.th/FDA_SEARCH_DRUG/SEARCH_DRUG/pop-up_drug.aspx?Newcode_U=U1DR1C1012480011711C. Accessed 28 Sep 2018.

- 8.Ministry of Public Health—Thailand. Product Review (Rotateq). http://pertento.fda.moph.go.th/FDA_SEARCH_DRUG/SEARCH_DRUG/pop-up_drug.aspx?Newcode_U=U1DR1C10B2510002311C. Accessed 28 Sep 18.

- 9.European Medicine Agency (EMA). Rotarix: EPAR—Product information London, UK: European Medicines Agency; 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/rotarix. Accessed 28 Sep 18.

- 10.European Medicine Agency (EMA). Rotateq: EPAR—Product information London, UK: European Medicines Agency; 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/rotateq. Accessed 28 Sep 18.

- 11.Gastanaduy PA, Contreras-Roldan I, Bernart C, et al. Effectiveness of monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccines in guatemala. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(Suppl 2):S121–S126. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Immergluck LC, Parker TC, Jain S, et al. Sustained effectiveness of monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccines in children. J Pediatr. 2016;172(116–20):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonesteller CL, Burnett E, Yen C, Tate JE, Parashar UD. Effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination: a systematic review of the first decade of global post-licensure data, 2006–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(5):840–850. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leshem E, Lopman B, Glass R, et al. Distribution of rotavirus strains and strain-specific effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccine after its introduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):847–856. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70832-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne DC, Selvarangan R, Azimi PH, et al. Long-term consistency in rotavirus vaccine protection: RV5 and RV1 vaccine effectiveness in US children, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(12):1792–1799. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhlig U, Kostev K, Schuster V, Koletzko S, Uhlig HH. Impact of rotavirus vaccination in Germany: rotavirus surveillance, hospitalization, side effects and comparison of vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(11):e299–e304. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO). Detailed review paper on rotavirus vaccines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2009. http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/3_Detailed_Review_Paper_on_Rota_Vaccines_17_3_2009.pdf. Accessed 03 Jan 17.

- 18.Rosillon D, Buyse H, Friedland LR, Ng S-P, Velázquez FR, Breuer T. Risk of Intussusception After Rotavirus Vaccination: meta-analysis of Postlicensure Studies. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(7):763–768. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calnan M, Krishnarajah G, Duh MS, et al. Rotavirus vaccination in a Medicaid infant population from four US states: compliance, vaccination completion rate, and predictors of compliance. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(5):1235–1243. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1136041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishnarajah G, Davis EJ, Fan Y, Standaert BA, Buikema AR. Rotavirus vaccine series completion and adherence to vaccination schedules among infants in managed care in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3717–3722. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnarajah G, Landsman-Blumberg P, Eynullayeva E. Rotavirus vaccination compliance and completion in a Medicaid infant population. Vaccine. 2015;33(3):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luna-Casas G, Juliao P, Carreno-Manjarrez R, et al. Vaccine coverage and compliance in Mexico with the two-dose and three-dose rotavirus vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1540827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chotivitayatarakorn P, Chotivitayatarakorn P, Poovorawan Y. Cost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination as part of the national immunization program for Thai children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(1):114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muangchana C, Riewpaiboon A, Jiamsiri S, Thamapornpilas P, Warinsatian P. Economic analysis for evidence-based policy-making on a national immunization program: a case of rotavirus vaccine in Thailand. Vaccine. 2012;30(18):2839–2847. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tharmaphornpilas P, Jiamsiri S, Boonchaiya S, et al. Evaluating the first introduction of rotavirus vaccine in Thailand: moving from evidence to policy. Vaccine. 2017;35(5):796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tharmaphornpilas P, Jiamsiri S, Tuntiwitayapun S, Boonchaiya S. [Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Rotavirus Vaccine in Pilot Provinces (Petchaboon and Sukhothai)] 2015. http://doi.nrct.go.th/ListDoi/Download/299915/570791963bf3929c4c93a81c5c2cce79?Resolve_DOI=10.14455/NRCT.res.2015.121. Accessed 18 Jul 18.

- 27.Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP). Guidelines for Health Technology Assessment in Thailand (Second Edition). Bangkok, Thailand: The Medical Association of Thailand; 2014. http://www.hitap.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Thai-HTA-guideline-UPDATES-Jmed-with-Cover.pdf. Accessed 17 Jul 18.

- 28.Alkoshi S, Maimaiti N, Dahlui M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of rotavirus vaccination among Libyan children using a simple economic model. Libyan J Med. 2014;9(1):26236. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v9.26236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakir M, Standaert B, Turel O, Bilge ZE, Postma M. Estimating and comparing the clinical and economic impact of paediatric rotavirus vaccination in Turkey using a simple versus an advanced model. Vaccine. 2013;31(6):979–986. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee I-H, Standaert B, Nievera MC, Rogacion J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of universal mass vaccination with Rotarix® in the Philippines. Ped Inf Dis Soc Phil. 2014;15(1):15–29. https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://www.pidsphil.org/pdf/Journal_08312014/jo46_ja03.pdf. Accessed 01 Oct 18.

- 31.Goossens LM, Standaert B, Hartwig N, Hovels AM, Al MJ. The cost-utility of rotavirus vaccination with Rotarix (RIX4414) in the Netherlands. Vaccine. 2008;26(8):1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standaert B, Parez N, Tehard B, Colin X, Detournay B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of vaccination against rotavirus with RIX4414 in France. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2008;6(4):199–216. doi: 10.1007/BF03256134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandran A, Fitzwater S, Zhen A, Santosham M. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants and children: rotavirus vaccine safety, efficacy, and potential impact of vaccines. Biologics. 2010;4:213–229. doi: 10.2147/btt.s6530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho AM, Nelson EA, Walker DG. Rotavirus vaccination for Hong Kong children: an economic evaluation from the Hong Kong Government perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):52–58. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.117879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR, et al. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization (WHO). Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper—summary 2013. https://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/PP_rotavirus_january_2013_summary.pdf. Accessed 01 Apr 19.

- 37.Tate JE, Mwenda JM, Parashar UD. Intussusception after rotavirus vaccination in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(13):1288–1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1807645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotirum S, Vutipongsatorn N, Kongpakwattana K, Hutubessy R, Chaiyakunapruk N. Global economic evaluations of rotavirus vaccines: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2017;35(26):3364–3386. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimdet K, Ngorsuraches S. Willingness to pay per quality-adjusted life year for life-saving treatments in Thailand. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e008123. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leelahavarong P. Budget impact analysis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:S65–S71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohara A, Youngkong S, Velasco RP, et al. Using health technology assessment for informing coverage decisions in Thailand. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(2):137–146. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Official Statistics Registration Systems. [Population and housing statistics—Population age] 2018. http://stat.dopa.go.th/stat/statnew/upstat_age.php. Accessed 30 Jan 18.

- 43.Loganathan T, Ng CW, Lee WS, Jit M. The hidden health and economic burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in Malaysia: an estimation using multiple data sources. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(6):601–606. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization (WHO). Child rotavirus deaths by country 2000–2013 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2016. 15-Apr-16. http://www.who.int/entity/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/rotavirus_deaths_by_country_2000-2013.xlsx. Accessed 12 Oct 17.

- 45.Ministry of Public Health. Public Health Statistics 2016. http://bps.moph.go.th/new_bps/sites/default/files/health_strategy2559.pdf. Accessed 07 Dec 17.

- 46.Li RC, Huang T, Li Y, et al. Human rotavirus vaccine (RIX4414) efficacy in the first two years of life: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(1):11–18. doi: 10.4161/hv.26319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burnett E, Parashar U, Tate J. Rotavirus vaccines: effectiveness, safety, and future directions. Paediatr Drugs. 2018;20(3):223–233. doi: 10.1007/s40272-018-0283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopman BA, Pitzer VE. Waxing understanding of waning immunity. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(6):851–853. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phua KB, Lim FS, Lau YL, et al. Rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 efficacy sustained during the third year of life: a randomized clinical trial in an Asian population. Vaccine. 2012;30(30):4552–4557. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The World Bank. Thailand now an upper middle income economy Washington DC, USA The World Bank Group; 2011. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2011/08/02/thailand-now-upper-middle-income-economy. Accessed 23 May 18.

- 51.UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Child Mortality Estimates 2016. http://www.childmortality.org/. Accessed 02 Oct 18.

- 52.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory Data, Under-five mortality Geneva, Switzerland. 2018. http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/mortality_under_five_text/en/. Accessed 23 May 18.

- 53.World Health Organization (WHO). Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) Fact Sheet 2017: 16. http://www.searo.who.int/immunization/data/thailand_2017.pdf. Accessed 30 Jan 18.

- 54.Riera-Montes M, O’Ryan M, Verstraeten T. Norovirus and rotavirus disease severity in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;37(6):501–505. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ministry of Commerce—Thailand. Report for Consumer Price Index of Thailand 2009. http://www.indexpr.moc.go.th/price_present/TableIndexG_region.asp?table_name=cpig_index_country&province_code=5&type_code=g&check_f=i&year_base=2558&nyear=2552. Accessed 30 Jan 18.

- 56.Ministry of Commerce—Thailand. Report for Consumer Price Index of Thailand 2014. http://www.indexpr.moc.go.th/price_present/TableIndexG_region.asp?table_name=cpig_index_country&province_code=5&type_code=g&check_f=i&year_base=2558&nyear=2557. Accessed 30 Jan 18.

- 57.Ministry of Commerce - Thailand. Report for Consumer Price Index of Thailand 2017. http://www.indexpr.moc.go.th/price_present/TableIndexG_region.asp?table_name=cpig_index_country&province_code=5&type_code=g&check_f=i&year_base=2558&nyear=2560. Accessed 30 Jan 18.

- 58.Riewpaiboon A. Measurement of costs for health economic evaluation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:S17–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bank of Thailand. Rates of Exchange of Commercial Banks in Bangkok Metropolis (2002-present). 2017. http://www2.bot.or.th/statistics/ReportPage.aspx?reportID=123&language=eng. Accessed 21 Feb 18.

- 60.Riewpaiboon A. Standard cost lists for health economic evaluation in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(Suppl 5):S127–S134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saokaew S, Permsuwan U, Chaiyakunapruk N, Nathisuwan S, Sukonthasarn A, Jeanpeerapong N. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-participated warfarin therapy management in Thailand. Thromb Res. 2013;132(4):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2000–2015 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/. Accessed 24 Jul 18.

- 63.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Methods for Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2014. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/LT_method_1990_2012.pdf. Accessed 24 Jul 18.

- 64.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory Data Repository Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.61640?lang=en. Accessed 24 Jul 17.

- 65.Rochanathimoke O, Riewpaiboon A, Postma MJ, Thinyounyong W, Thavorncharoensap M. Health related quality of life impact from rotavirus diarrhea on children and their family caregivers in Thailand. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(2):215–222. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2018.1386561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaikledkaew U. Presentation of economic evaluation results. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(Suppl 5):S72–S80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Permsuwan U, Guntawongwan K, Buddhawongsa P. Handling time in economic evaluation studies. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(Suppl 2):S53–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Limwattananon S. Sensitivity analysis for handling uncertainty in an economic evaluation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(Suppl 5):S59–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies which evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. To access data for other types of GSK sponsored research, for study documents without patient-level data and for clinical studies not listed, please submit an enquiry via the website.