Abstract

Introduction

Prednisone is frequently administered in combination with other therapies for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA); however, its chronic use is associated with an increased risk of comorbidities and mortality. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate changes in prednisone use among patients with RA treated with tocilizumab (TCZ) in routine US clinical practice.

Methods

TCZ-naïve patients in the Corrona RA registry who initiated TCZ were included. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with changes in prednisone use over 12 months (primary analysis) and 6 months (secondary analysis). Changes in disease activity over 6 and 12 months (± 3 months) were assessed using the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI). Outcomes were assessed in the overall population and separately for patients receiving TCZ monotherapy or in combination with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Results

Of patients receiving prednisone at baseline (mean [SD] dose: 7.7 [5.2] mg/day), 30.6% discontinued prednisone over 12 months; among patients receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at the time of TCZ initiation, 63.0% discontinued prednisone or decreased their dose by ≥ 5 mg over 12 months. In secondary analyses, 29.7% of patients receiving prednisone at baseline had discontinued prednisone over 6 months; among those receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at baseline, 51.3% discontinued or decreased their dose by ≥ 5 mg over 6 months. Changes in prednisone use and improvement from baseline in CDAI score over 6 and 12 months were comparable between patients who initiated TCZ monotherapy vs. TCZ combination therapy.

Conclusions

In this real-world analysis, many patients initiating TCZ monotherapy or combination therapy were able to discontinue or decrease their prednisone dose over 12 months. Similar changes in prednisone dose were observed over 6 months.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01402661.

Funding

Corrona, LLC and Genentech, Inc.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Keywords: Prednisone, Registry, Rheumatoid arthritis, Tocilizumab

Plain Language Summary

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can lead to joint damage and disability. The steroid prednisone is a fast-acting and effective treatment for RA and is often prescribed alongside disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The health risks associated with the long-term use of prednisone have led to recommendations to minimize prednisone dose and duration of treatment. Few studies have examined the extent to which biologic DMARDs allow rheumatologists to reduce or discontinue the use of prednisone. The objective of this study was to evaluate changes in prednisone dose while receiving tocilizumab (TCZ) in patients with RA seen in routine US clinical practice. Patients who were enrolled in the Corrona RA registry and were beginning treatment with TCZ were included. Changes in prednisone use were evaluated 12 months after starting treatment. Of patients receiving prednisone at study initiation, 30.6% had discontinued prednisone over 12 months; among patients receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at the time of TCZ initiation, 63.0% discontinued prednisone or decreased the dose by ≥ 5 mg over 12 months. In secondary analyses, 29.7% of patients receiving prednisone at study initiation had discontinued prednisone over 6 months; among those receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at baseline, 51.3% discontinued or decreased the dose by ≥ 5 mg over 6 months. Changes in prednisone use and improvement in disease activity over 6 and 12 months were comparable between patients who initiated TCZ monotherapy or combination therapy with other DMARDs.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic and progressive autoimmune disease characterized by joint swelling, pain, and stiffness due to synovial inflammation [1]. Joint damage and resultant disability occur without prompt and adequate treatment. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have made control of disease activity (remission or low disease activity) a realistic goal. However, DMARDs may take weeks to exert their therapeutic benefits, whereas steroids have fast-acting effects. Thus, at the initiation of DMARD treatment, steroids are frequently co-administered as “bridging therapy”.

Many patients continue taking steroids for extended periods of time. Studies have shown that up to 65% of patients with RA receive steroids [2, 3], despite guidelines suggesting that steroids should only be used when disease activity remains high or during disease flares and only for a short duration at the lowest possible dose [4]. Chronic use of steroids such as prednisone is associated with an increased risk of several comorbidities, including osteoporosis, cataracts, hypertension, and weight gain [5, 6], and is associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality in patients with RA [7]. The extent to which biologics allow rheumatologists to reduce or discontinue the use of steroids has not been extensively evaluated.

Tocilizumab (TCZ) is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the interleukin-6 receptor [8]. TCZ is approved for patients with moderate to severe RA who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate or other biologics [8]. Clinical studies have shown that TCZ administered as monotherapy [9, 10] or in conjunction with conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) [8, 11–13] effectively reduces disease activity in patients with RA. Evidence shows that TCZ may reduce the need for therapy with prednisone in patients with RA. The Strategies in Early Arthritis Management (STREAM) clinical trial [14] and real-world studies of routine practice patterns conducted in Japan [15], France [16, 17], Australia [18], Germany [19], and multinational settings [20] demonstrated steroid-sparing effects of TCZ in patients with RA. The use of prednisone in patients receiving TCZ within the United States has not been evaluated using real-world data. We designed the present analysis to characterize real-world changes in prednisone use after initiation of TCZ using data from a large US-based RA registry (Corrona). TCZ is frequently administered as monotherapy [20]; clinical studies have shown comparable outcomes in patients receiving TCZ monotherapy or TCZ in combination with csDMARDs [10, 21], and data from observational studies suggest that TCZ has similar effectiveness when administered as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs [20, 22]. We therefore evaluated the effect of TCZ on prednisone use in an overall population of TCZ initiators and in subgroups of patients who initiated TCZ monotherapy or TCZ in combination with csDMARDs.

Methods

Study Setting

Data were obtained from the Corrona RA registry (NCT01402661), an independent, prospective, observational cohort of patients with RA [23, 24]. The registry includes patients recruited from 177 private and academic practice sites across 42 states in the United States, with 736 participating rheumatologists. As of June 2018, data on 49,162 patients with RA have been collected. Corrona’s database includes information from 373,064 patient visits and 173,389 patient-years of follow-up. The mean duration of patient follow-up is 4.4 years (median, 3.3 years).

The study was conducted according to the current (2013) version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from a central institutional review board (New England Independent Review Board, IRB 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs and documentation of approval was submitted to the sponsor before initiation of any study procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Patient Population and Data Collection

Eligible participants were TCZ-naïve patients with RA aged ≥ 18 years participating in the Corrona registry. Participants initiated TCZ on or after January 1, 2010, had a 12-month (± 3 months) follow-up visit without discontinuation of TCZ, and had prednisone use information available at time of TCZ initiation and at follow-up. Data from Corrona were collected from physician and patient questionnaires completed during routine clinical encounters that occurred over the 12-month study period. Data recorded at the time of clinical encounter within Corrona include patient demographics, clinical characteristics, laboratory measurements, history of comorbidities, current and prior medication use, clinical disease activity measures, and patient-reported outcome measures. Variables assessed in this analysis included patient demographics (age, sex, race, smoking status, body mass index, insurance), disease duration, history of comorbidities, treatment history, prednisone use and dose, and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score.

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were described for the overall cohort and separately for patients initiating TCZ as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs. Baseline characteristics were compared between the TCZ monotherapy and TCZ combination therapy groups using two-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients in the overall population of TCZ initiators with changes in prednisone use (initiation, discontinuation, or dose escalation/reduction of ≥ 5 mg) over 12 months (± 3 months). In a secondary analysis, changes in prednisone use were assessed in the subset of patients who had a 6-month (± 3 months) follow-up visit. Patients with a visit outside of the 12-month (± 3 months) or 6-month (± 3 months) window or without prednisone dose information available at the follow-up visit were excluded from the primary or secondary analysis, respectively. Descriptive analysis of changes in prednisone use was conducted separately for patients receiving TCZ monotherapy and TCZ in combination with csDMARDs. Change from baseline in CDAI score was summarized descriptively at 6 and 12 months.

Results

Study Population

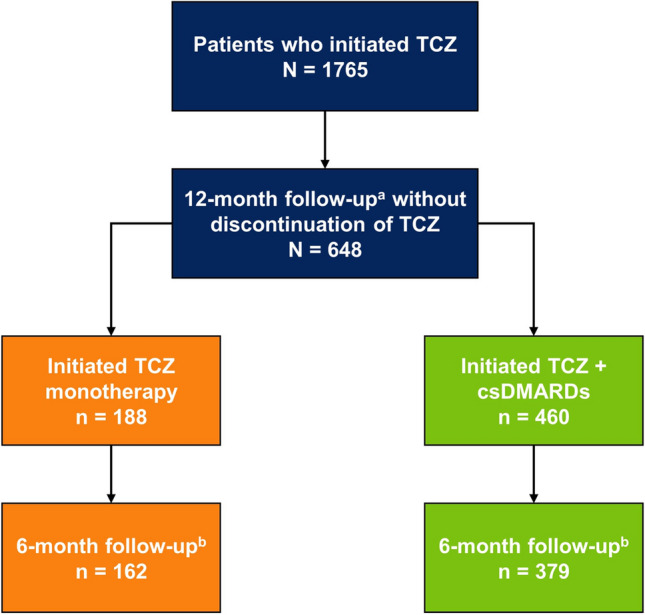

There were 648 TCZ initiators who met the inclusion criteria; 188 (29%) initiated TCZ monotherapy and 460 (71%) initiated TCZ in combination with csDMARDs (Fig. 1). Of the 648 patients included in the primary analysis, 541 (83.5%) also had a 6-month (± 3 months) follow-up visit [TCZ monotherapy, n = 162 (29.9%); TCZ + csDMARDs, n = 379 (70.1%)] and were included in the secondary analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition. aThe 12-month follow-up visit occurred in a window of 9–15 months. bThe 6-month follow-up visit occurred in a window of 3–9 months. Patients with a visit outside of the 3- to 9-month window or patients without prednisone dose information available at the 6-month (± 3 months) visit were excluded. csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, TCZ tocilizumab

Patient Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Patient baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment history are described in Table 1. Overall, most patients were female (79.8%) and white (86.8%), with a mean (SD) age of 58.6 (11.8) years. Approximately half of the patients (45.3%) were current or former smokers. The majority of patients were overweight or obese (75.9%). The overall mean (SD) disease duration was 12.5 (9.1) years, and the mean (SD) CDAI score at baseline was 24.4 (14.4). Most patients (72.8%) had received ≥ 2 prior biologics, with 54.9% having received ≥ 2 prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis). At baseline, 222 patients (34.3%) were receiving prednisone [mean (SD) dose: 7.7 (5.2) mg], and 426 (65.7%) were not. Of the 222 patients treated with prednisone at baseline, 130 (58.6%) received ≤ 7.5 mg and 92 (41.4%) received > 7.5 mg.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment history

| Characteristic | All patients (N = 648) | TCZ monotherapy (n = 188) | TCZ + csDMARDs (n = 460) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 58.6 (11.8) | 60.5 (11.1) | 57.9 (12.0) | 0.01 |

| Female, n (%) | 517 (79.8) | 151 (80.3) | 366 (79.6) | 0.83 |

| Race, n (%)a | ||||

| White | 559 (86.8) | 168 (89.8) | 391 (85.6) | 0.28 |

| Black | 27 (4.2) | 4 (2.1) | 23 (5.0) | |

| Asian | 12 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 10 (2.2) | |

| Other | 46 (7.1) | 13 (7.0) | 33 (7.2) | |

| Smoking status, n (%)a | ||||

| Current | 79 (12.3) | 23 (12.4) | 56 (12.2) | 0.30 |

| Previous | 212 (33.0) | 69 (37.3) | 143 (31.2) | |

| Never | 352 (54.7) | 93 (50.3) | 259 (56.6) | |

| Weight, mean (SD), lb | 181.4 (46.6) | 174.0 (42.3) | 184.4 (48.0) | 0.01 |

| BMI category, n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 6 (0.9) | 3 (1.6) | 3 (0.7) | 0.35 |

| Normal weight | 150 (23.1) | 47 (25.0) | 103 (22.4) | |

| Overweight | 218 (33.6) | 67 (35.6) | 151 (32.8) | |

| Obese | 274 (42.3) | 71 (37.8) | 203 (44.1) | |

| Insurance, n (%)b | ||||

| Private | 500 (77.2) | 135 (71.8) | 365 (79.3) | 0.04 |

| Medicaid | 30 (4.6) | 9 (4.8) | 21 (4.6) | 0.90 |

| Medicare | 243 (37.5) | 78 (41.5) | 165 (35.9) | 0.18 |

| None | 3 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.15 |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), years | 12.5 (9.1) | 13.6 (9.8) | 12.0 (8.8) | 0.08 |

| History of comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 216 (33.3) | 61 (32.4) | 155 (33.7) | 0.76 |

| Diabetes | 68 (10.5) | 20 (10.6) | 48 (10.4) | 0.94 |

| Malignancy | 65 (10.0) | 18 (9.6) | 47 (10.2) | 0.80 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 61 (9.4) | 20 (10.6) | 41 (8.9) | 0.49 |

| CDAI score, mean (SD) | 24.4 (14.4) | 24.5 (12.8) | 24.3 (15.1) | 0.92 |

| Patient-reported fatigue, mean (SD), 0–100 | 54.2 (27.6) | 57.3 (26.0) | 53.0 (28.1) | 0.10 |

| No. of prior csDMARDs, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 18 (2.8) | 14 (7.4) | 4 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 217 (33.5) | 59 (31.4) | 158 (34.3) | |

| ≥ 2 | 413 (63.7) | 115 (61.2) | 298 (64.8) | |

| No. of prior biologics, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 23 (3.5) | 8 (4.3) | 15 (3.3) | 0.81 |

| 1 | 153 (23.6) | 45 (23.9) | 108 (23.5) | |

| ≥ 2 | 472 (72.8) | 135 (71.8) | 337 (73.3) | |

| No. of prior TNFis, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 54 (8.3) | 24 (12.8) | 30 (6.5) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 238 (36.7) | 63 (33.5) | 175 (38.0) | |

| ≥ 2 | 356 (54.9) | 101 (53.7) | 255 (55.4) | |

| Current prednisone use, n (%) | ||||

| None | 426 (65.7) | 124 (66.0) | 302 (65.7) | 0.26 |

| ≤ 7.5 mg | 130 (20.1) | 32 (17.0) | 98 (21.3) | |

| > 7.5 mg | 92 (14.2) | 32 (17.0) | 60 (13.0) | |

| Prednisone dose, mean (SD)c | 7.7 (5.2) | 7.9 (4.4) | 7.6 (5.4) | 0.29 |

BMI body mass index, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, RA rheumatoid arthritis, TCZ tocilizumab, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

aData not available for all patients

bSum may not add to total N due to overlapping insurance groups

cCalculated for only those patients taking prednisone at initiation

Patients who initiated TCZ monotherapy were older (mean age, 60.5 vs. 57.9 years; P = 0.01), weighed less (mean weight, 174.0 vs. 184.4 lb; P = 0.01), and were less likely to have private insurance (71.8 vs. 79.3%; P = 0.04) than patients receiving TCZ combination therapy. Patients receiving TCZ monotherapy had previously received fewer csDMARDs (P < 0.001) and TNFis (P = 0.03) compared with patients receiving TCZ combination therapy. There were no significant differences in disease duration, CDAI score, or prednisone use between patients receiving TCZ monotherapy and patients receiving TCZ combination therapy.

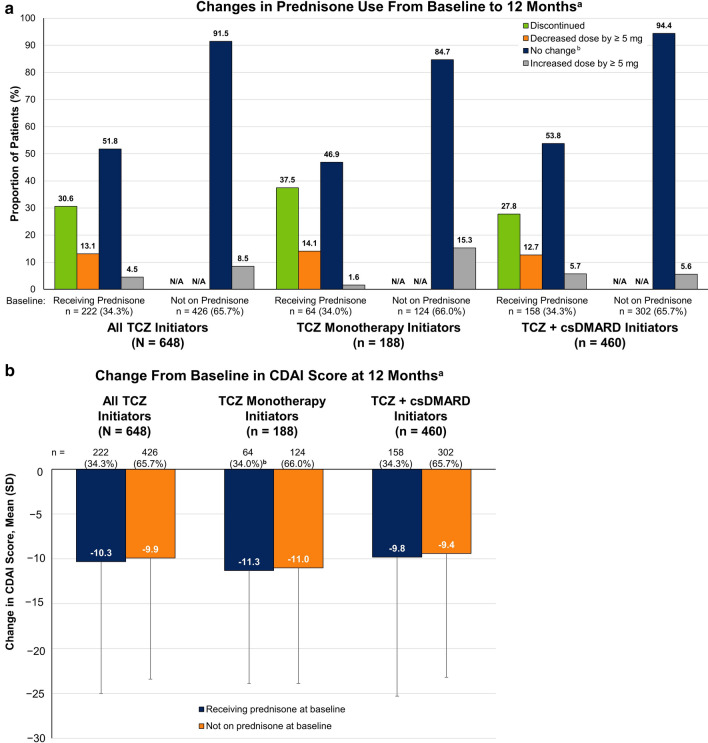

Changes From Baseline in Prednisone Use and CDAI Score Over 12 Months

Changes in prednisone use, including discontinuation and dose reduction of ≥ 5 mg, were observed over 12 months following TCZ initiation (Fig. 2a). Of the 222 patients receiving prednisone at baseline, 130 (58.6%) were receiving ≤ 7.5 mg of prednisone. Of these, 1 (0.8%) had a dose decrease of ≥ 5 mg and 38 (29.2%) discontinued prednisone (Table 2). Among the 92 patients (41.4%) receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at baseline, 28 (30.4%) decreased the dose by ≥ 5 mg and 30 (32.6%) discontinued prednisone (Table 2). Overall, 30.6% discontinued prednisone and 13.1% decreased the dose of prednisone by ≥ 5 mg over 12 months (mean change of − 8.68 mg; data not shown). Among the 426 patients not receiving prednisone at baseline, 36 (8.5%) initiated prednisone over 12 months. Changes in prednisone exhibited similar patterns regardless of whether patients were receiving TCZ monotherapy or combination therapy (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Change from baseline in (a) prednisone use and (b) CDAI score at the 12-month follow-up visit in patients with RA who initiated TCZ. aThe 12-month follow-up visit occurred in a window of 9–15 months; comparisons between subgroups are descriptive in nature. bIncludes patients with change in dose of < 5 mg. CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, N/A not applicable, RA rheumatoid arthritis, TCZ tocilizumab

Table 2.

Change in prednisone use at 6 and 12 months by prednisone dose at baseline

| All patientsa | Prednisone at TCZ initiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not receiving prednisone | Prednisone dose ≤ 7.5 mg | Prednisone dose > 7.5 mg | ||

| 6 months | ||||

| All patients with a 6-month visit | 541 | 356 | 107 | 78 |

| No change in prednisone dose, n (%)b | 426 (78.7) | 327 (91.9) | 67 (62.6) | 32 (41.0) |

| Increased dose by ≥ 5 mg, n (%) | 39 (7.2) | 29 (8.1) | 4 (3.7) | 6 (7.7) |

| Decreased dose by ≥ 5 mg, n (%)c | 21 (3.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 20 (25.6) |

| Stopped prednisone, n (%) | 55 (10.2) | 0 | 35 (32.7) | 20 (25.6) |

| 12 months | ||||

| All patients with a 12-month visit | 648 | 426 | 130 | 92 |

| No change in prednisone dose, n (%)b | 505 (77.9) | 390 (91.5) | 84 (64.6) | 31 (33.7) |

| Increased dose by ≥ 5 mg, n (%) | 46 (7.1) | 36 (8.5) | 7 (5.4) | 3 (3.3) |

| Decreased dose by ≥ 5 mg, n (%)c | 29 (4.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 28 (30.4) |

| Stopped prednisone, n (%) | 68 (10.5) | 0 | 38 (29.2) | 30 (32.6) |

TCZ tocilizumab

aWith a visit at 6 or 12 months

bAlso includes those with < 5 mg change in prednisone dose

cDoes not include patients who discontinued prednisone

Improvement from baseline in CDAI score was observed 12 months after TCZ initiation among both patients who were receiving prednisone at TCZ initiation (overall mean change, − 10.3) and those who were not receiving prednisone at TCZ initiation (overall mean change, − 9.9) and was comparable between patients receiving TCZ monotherapy and those receiving TCZ combination therapy (Fig. 2b).

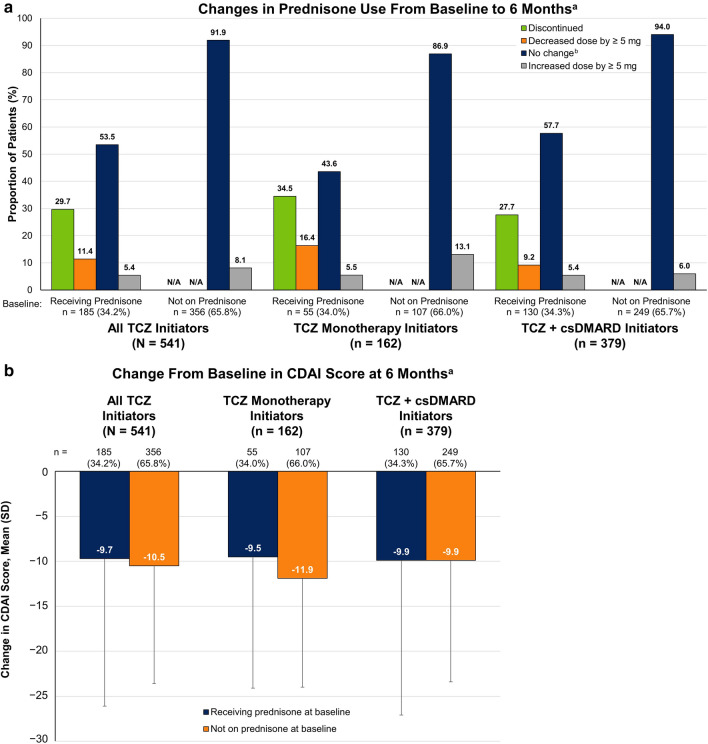

Changes From Baseline in Prednisone Use and CDAI Score Over 6 Months

Changes in prednisone use were also observed over 6 months following TCZ initiation (Fig. 3a). Of the 185 patients receiving prednisone at baseline, 107 (57.8%) were receiving ≤ 7.5 mg of prednisone, of whom 1 (0.9%) had a dose decrease of ≥ 5 mg and 35 (32.7%) discontinued prednisone (Table 2). Among the 78 patients (42.2%) receiving > 7.5 mg of prednisone at baseline, 20 (25.6%) decreased the dose by ≥ 5 mg and 20 (25.6%) discontinued prednisone (Table 2). Overall, 29.7% of patients receiving prednisone at baseline discontinued prednisone and 11.4% decreased the dose of prednisone by ≥ 5 mg over 6 months (mean change of − 9.5 mg; data not shown). Of the 356 patients not receiving prednisone at baseline, 29 (8.1%) initiated prednisone over 6 months. Similar patterns in prednisone changes over the first 6 months were observed for patients receiving TCZ monotherapy or combination therapy (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Change from baseline in (a) prednisone use and (b) CDAI score at the 6-month follow-up visit in patients with RA who initiated TCZ. aIncludes only those patients with a 6-month (± 3 months) follow-up visit with prednisone dose information available; comparisons between subgroups are descriptive in nature. bIncludes patients with change in dose of < 5 mg. CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, N/A not applicable, RA rheumatoid arthritis, TCZ tocilizumab

Improvement from baseline in CDAI score was observed 6 months after TCZ initiation among both patients who were receiving prednisone at TCZ initiation (overall mean change, − 9.7) and those who were not receiving prednisone at TCZ initiation (overall mean change, − 10.5) and was comparable between the TCZ monotherapy and combination therapy groups (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

Prednisone is frequently administered to patients with RA in combination with DMARDs; however, chronic use of prednisone is associated with an increased risk of several comorbidities and increased mortality [5–7]. The present study sought to evaluate the prednisone-sparing effects of the biologic DMARD TCZ using real-world clinical data. Changes in prednisone use were observed at 6-month and 12-month follow-up visits after TCZ initiation, with comparable proportions of patients who had discontinued prednisone (29.7 and 30.6%, respectively), decreased prednisone dose (11.4 and 13.1%), and initiated prednisone (8.1 and 8.5%) at both time points. Improvements in baseline CDAI scores were also observed over 6 and 12 months after TCZ initiation. Additionally, patients were stratified into subgroups by treatment with TCZ monotherapy or TCZ in combination with csDMARDs to describe patterns of prednisone use. Both groups showed similar changes in prednisone use over 6 and 12 months.

Our findings showed that many patients who initiated TCZ monotherapy or combination therapy were able to discontinue or lower the dose of prednisone over a 12-month period. These findings are supported by prior reports of corticosteroid use in patients receiving TCZ therapy, which showed steroid-sparing effects of TCZ irrespective of treatment protocol [14–20]. Consistent with our results, corticosteroid discontinuation rates of 34.1 and 31.8% at 52 weeks [15] and 5 years [14] after TCZ initiation, respectively, were reported in an observational study [15] and in a clinical trial conducted in Japan [14]. Similarly, decreases in corticosteroid dose and discontinuation of corticosteroids were observed following initiation of TCZ monotherapy [14, 20] or TCZ combination therapy [15, 20] in previous real-world studies outside the United States and clinical trials. A multinational investigation of TCZ use in routine clinical practice (ACT-UP) reported that patients receiving TCZ monotherapy or TCZ administered with csDMARDs had comparable rates of increased (12.4 and 10.4%, respectively) and decreased (28.8 and 22.4%, respectively) corticosteroid dose at 6 months after initiation of TCZ [20]. Although the proportions of patients with corticosteroid dose adjustments are larger than those observed in the Corrona RA registry, patients in the ACT-UP study had a higher level of disease activity at baseline, which may have necessitated a greater amount of treatment modification.

A major strength of our study is the source of our patient data—Corrona is the largest disease-based registry in the United States, which allowed for the inclusion of a large number of patients who had initiated TCZ. Because data in this registry are collected at regular intervals from both physicians and patients, we were able to evaluate outcomes at two different time points.

One potential limitation in every registry-based analysis is whether findings are representative of and generalizable to the broader population. Corrona is the largest disease-based registry in the United States, with rheumatology practices participating throughout the country in rural and urban areas in academic and private settings and with access to broad geographic locations and patients with diverse sociodemographic origins. Therefore, observations made in the Corrona population have implications for the general RA population. In addition, analyses investigating similarities between patients enrolled in the registry and those in the general population further support the generalizability of the Corrona registry [23]. Because the goal of this study was to describe the patterns of prednisone changes in a real-world setting and not to investigate associations and causalities between TCZ monotherapy vs. combination therapy or treatment response, this study presented descriptive data without matching of patients or adjustments of statistical imbalances between the different patient groups that were presented. Changes in prednisone use were evaluated using two timepoints (baseline and 6- or 12-month follow-up); thus, it is possible that patients may have had interval changes between the baseline and follow-up visits that were not captured in this analysis. However, our intent was not to compare differences in cumulative prednisone intake or describe real-time changes in prednisone dose; rather, our goal was to evaluate the total change in prednisone dose after a predefined period of therapy. Our analysis was limited to patients who continued TCZ for 12 months; patients who discontinued TCZ for any reason, including inadequate response or adverse events, were excluded. Thus, the results of this study demonstrate the impact of TCZ on prednisone use for patients who tolerate TCZ treatment and do not discontinue TCZ for any reason prior to 12 months and may not be generalizable to patients who discontinue TCZ within the first year of initiation.

Future analyses will potentially assess the prednisone-sparing effects of TCZ in patients with different biologic treatment histories. The majority of patients in the present study (72.8%) had been previously treated with ≥ 2 biologic DMARDs, with 54.9% of patients receiving ≥ 2 prior TNFis. It is unclear from the present analysis whether similar prednisone-sparing effects occur in patients receiving TCZ as first-line therapy. A recent real-world analysis of patients with RA (in the German biologics register RABBIT) found no difference in mean glucocorticoid dose between patients receiving TCZ as first-line, second-line, third-line, or fourth-line therapy [19], suggesting that prior biologic DMARD failure may not influence patterns of prednisone use in patients with RA treated with TCZ.

Conclusions

In our retrospective real-world analysis, a considerable proportion of patients initiating TCZ were able to discontinue or lower the dose of prednisone over 12 months, with decreased prednisone use observed over the first 6 months after TCZ initiation. Changes in prednisone use were similar regardless of whether TCZ was administered as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs. These results suggest that treatment with TCZ may allow prednisone sparing in patients with RA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating providers and patients for contributing data to the Corrona RA Registry.

Funding

This study is sponsored by Corrona, LLC. Corrona, LLC has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last 2 years by AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, GSK, Horizon Pharma, Janssen, Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sun, and UCB. The study design and conduct were the result of a collaborative effort between Corrona, LLC, and Genentech, Inc., and financial support for the study was provided by Genentech, Inc. Genentech, Inc. participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript. Article processing charges were funded by Genentech, Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article, provided by Amanda Borrow, PhD, of Health Interactions, Inc., was funded by Genentech, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Dimitrios A. Pappas is an employee of Corrona, LLC, and a consultant for AbbVie and has received grant support from AbbVie. Carol J. Etzel is an employee and shareholder of Corrona, LLC, and is a member of an advisory board for Merck. Jennie Best is an employee and shareholder of Genentech, Inc. Steve Zlotnick is an employee and shareholder of Genentech, Inc. Taylor Blachley is an employee of Corrona, LLC. Joel M. Kremer is an employee and shareholder of Corrona, LLC, and a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi.

Compliance With Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted according to the current (2013) version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from a central institutional review board (New England Independent Review Board, IRB 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs and documentation of approval was submitted to the sponsor before initiation of any study procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of proprietary rights but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8204459.

References

- 1.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorter SL, Bijlsma JW, Cutolo M, et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with glucocorticoids: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1010–1014. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crane MM, Juneja M, Allen J, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of new-onset and established rheumatoid arthritis in an insured US population. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:1646–1655. doi: 10.1002/acr.22646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1–25. doi: 10.1002/acr.22783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J, et al. Population-based assessment of adverse events associated with long-term glucocorticoid use. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:420–426. doi: 10.1002/art.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bijlsma JW, Boers M, Saag KG, Furst DE. Glucocorticoids in the treatment of early and late RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1033–1037. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.11.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chester Wasko M, Dasgupta A, Ilse Sears G, Fries JF, Ward MM. Prednisone use and risk of mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: moderation by use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:706–710. doi: 10.1002/acr.22722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACTEMRA [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc. 2013.

- 9.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Tocilizumab combination therapy or monotherapy or methotrexate monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year clinical and radiographic results from the randomised, placebo-controlled FUNCTION trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1279–1284. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2-year randomised controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:43–50. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivitz A, Olech E, Borofsky M, et al. Subcutaneous tocilizumab versus placebo in combination with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1653–1661. doi: 10.1002/acr.22384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maini RN, Taylor PC, Szechinski J, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, tocilizumab, in European patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had an incomplete response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2817–2829. doi: 10.1002/art.22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:987–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J. Long-term safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (the STREAM study): evidence of safety and efficacy in a 5-year extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1580–1584. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishiguro N, Atsumi T, Harigai M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab in achieving clinical and functional remission, and sustaining efficacy in biologics-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the FIRST Bio study. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:217–226. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2016.1206507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortunet C, Pers YM, Lambert J, et al. Tocilizumab induces corticosteroid sparing in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:672–677. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saraux A, Rouanet S, Flipo RM, et al. Glucocorticoid-sparing in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and treated with tocilizumab: the SPARE-1 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones G, Hall S, Bird P, et al. A retrospective review of the persistence on bDMARDs prescribed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the Australian population. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:1581–1590. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baganz L, Richter A, Kekow J, et al. Long-term effectiveness of tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, stratified by number of previous treatment failures with biologic agents: results from the German RABBIT cohort. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:579–587. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3870-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haraoui B, Casado G, Czirjak L, et al. Patterns of tocilizumab use, effectiveness and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: core data results from a set of multinational observational studies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kremer JM, Rigby W, Singer NG, et al. Sustained response following discontinuation of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with subcutaneous tocilizumab: results from a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:1200–1208. doi: 10.1002/art.40493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauper K, Nordstrom DC, Pavelka K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of tocilizumab versus TNF inhibitors as monotherapy or in combination with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after the use of at least one biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug: analyses from the pan-European TOCERRA register collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1276–1282. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Chen L, Bharat A, et al. Linkage of a de-identified United States rheumatoid arthritis registry with administrative data to facilitate comparative effectiveness research. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1790–1798. doi: 10.1002/acr.22377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kremer JM. The Corrona US registry of rheumatic and autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(5 suppl 101):S96–S99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of proprietary rights but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.