Abstract

Background:

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is highly effective but also has higher initiation costs than oral contraceptive methods, which may contribute to relatively low use. The Affordable Care Act requires most private insurance plans to cover contraceptive services without patient cost-sharing. Whether this mandate will increase LARC use is unknown.

Objective:

To assess the relationship between cost-sharing and use of LARC among privately insured women.

Design:

Cross-sectional analysis using Truven Health MarketScan data from January 2011-December 2011.

Subjects:

Women aged 14-45 with continuous insurance coverage enrolled in health plan products that covered branded and generic oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). We selected women using OCPs and IUDs since these are the most commonly-used short-acting and long-acting reversible methods, respectively (N=1,682,425).

Measures:

Multivariable regression was used to assess the association of level of out-of-pocket costs for IUDs for each patient’s plan and IUD initiation, adjusting for out-of-pocket costs for branded and generic OCPs and patient characteristics.

Results:

Overall, 5.5% of women initiated an IUD in 2011. After adjustment, IUD initiation was less likely among women with higher vs. lower co-pays (adjusted RR=0.65, 95%CI:0.64-0.67). Women who saw an ob/gyn during 2011 were more likely to initiate an IUD (adjusted RR=2.49, 95%CI:2.45-2.53).

Conclusions:

Rates of IUD use are low among privately-insured women in the U.S., and higher cost-sharing is associated with lower rates of IUD use. Together with other measures to promote LARC use, eliminating co-pays for contraception could promote use of these more effective and cost-effective methods.

Keywords: contraception, intrauterine device, Affordable Care Act, mandate

Introduction

In August 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services adopted recommendations from an Institute of Medicine panel that a broad array of preventive services for women, including contraception, should be covered by most private health insurance plans without cost-sharing by patients.1 Implementation of this mandate began in August 2012. The impact of these expanded benefits on women’s contraceptive use is not yet known. However, data suggest that many women perceive cost as a barrier to contraceptive use,2,3, 4 and state-level comprehensive contraceptive coverage mandates have been associated with more consistent contraceptive use reported by privately insured women.5 Thus, proponents of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) legislation hope that eliminating cost-sharing nationally will facilitate contraceptive use and adherence, potentially reducing high unintended pregnancy rates in the U.S.

Experts are particularly hopeful that eliminating cost-sharing could promote long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) use, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, since these are the most effective and cost-effective reversible methods available.6, 7,8, 9 Since the effectiveness of LARC methods is not user-dependent, LARC is far more effective than short-acting methods in preventing unintended pregnancy.10, 11 For example, in a recent prospective study, the contraceptive failure rate was 0.27 per 100 participant-years for individuals using LARC and 4.55 per 100 participant-years for individuals using pills, patches or vaginal rings. 10 Furthermore, once these methods are in use, discontinuation rates are considerably lower than other contraceptive methods.12 However, despite increasing rates of LARC use in recent years, only 8.5% of contraceptive users in the US use LARC.13, 14 LARC methods often entail high initial costs, including for privately insured women,15 and some data suggest that higher cost-sharing is a deterrent to LARC use.6,16,17However, other major barriers to LARC use exist in the U.S., including patient and provider knowledge and attitudes regarding contraception in general and IUDs in particular.18 Existing data are insufficient to accurately predict the impact of out-of-pocket cost elimination on LARC use nationally.

Some evidence suggests that eliminating cost-sharing could substantially increase LARC use. The Contraceptive CHOICE project enrolled 9,256 women in the Saint Louis area, 57%of whom were uninsured or publicly insured, and provided them with free contraceptives of their choice. Participants also received education by trained providers with a particular focus on LARC methods. Most participants (75%) selected a LARC method. During the study period, from 2008-2010, teen birth rates among CHOICE participants were far below the national average, and the abortion rate in St Louis fell by 20.6%, with no contemporaneous change in rates in Missouri as a whole.8, 19 Similarly, at Kaiser Permanente, LARC use increased with the elimination of cost-sharing and provider education.17 Both of these studies suggest that eliminating cost-sharing is a promising approach to increasing uptake of LARC. However, because both of these studies targeted specific populations and included other interventions, they cannot estimate the impact of the ACA mandates on contraception use patterns nationally.

Decision-making around contraceptive use is complex and influenced by patient, provider, and health system factors, including cost. Particularly given ongoing challenges to the contraceptive mandate, understanding the potential impact of eliminating cost-sharing on contraceptive use patterns among privately insured women nationally is important for clinicians, policymakers and insurers. The goal of this study was to characterize the relationship between out-of-pocket costs and LARC use, among women with employer-sponsored insurance across the U.S.

Methods

Data Source

We used the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database from January 1-December 31, 2011 for this cross-sectional analysis. This database represents over 50 million non-retired employees and their dependents enrolled in commercial employer health insurance plan products sponsored by over 100 large or medium sized U.S.-based employers. The data include monthly enrollment, inpatient and outpatient medical claims, outpatient prescription drug claims, and reimbursed amounts paid by the health plan and patient for services billed. The study protocol was considered exempt by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Subjects and Contraceptive Methods

We included women aged 14-45 with continuous health plan and prescription drug coverage who used IUDs or branded or generic oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) in 2011 and were enrolled in one of 4,176 employer health plan products that covered OCPs and IUDs (N=1,682,425). These plan products were identified by the presence of at least one reimbursed claim for branded OCPs, generic OCPs, and IUDs in 2011. A woman was considered to be using a given contraceptive method if her first contraceptive claim in 2011 was for that method.

We focused our analysis on reversible contraceptive methods. We examined OCP and IUD use because these are the most commonly-used short and long-acting reversible methods, respectively. Contraceptive implants were used too infrequently (<1% of women) to provide reliable estimates or to assess patient cost-sharing across plans.

Key Variables

The primary dependent variable was IUD use as opposed to OCP (branded or generic) use. The primary independent variable was level of out-of-pocket costs for IUDs for a given patient’s plan. We also examined out-of-pocket costs for branded and generic OCPs. For IUDs we estimated mean out-of-pocket costs for one IUD placement. For branded and generic oral contraceptives we estimated mean out-of-pocket costs for a single fill, standardized to a 28-day supply. These amounts represent the amounts paid by the patient for initiating a selected contraceptive method, including the copayment, co-insurance and deductible payments paid for the services received. Reimbursements for office visits or contraceptive counseling services were not included because these were assumed not to vary extensively between specific methods within a given plan. We categorized out-of-pockets costs as low, medium or high, with low costs corresponding to the costs for plans in the first quartile, medium costs corresponding to plans in the second and third quartiles, and high costs corresponding to plans in the fourth quartile of out-of-pocket costs. Other independent variables assessed included age, U.S. census region, whether a woman was a spouse, dependent or the insured employee, and whether an obstetrician/gynecologist (ob/gyn) had been seen during the year.

Statistical Analysis

First we described patient characteristics and use of IUDs and OCPs and level of cost-sharing by level of out-of-pocket costs for IUDs. Next we estimated the correlation between cost-sharing levels across contraceptive methods within plans, since high degrees of correlation between cost-sharing for different methods would impact our analysis of the relationship that co-pays for one method could have on use of another method. We then used generalized estimating equations with a log link and Poisson distribution to assess the likelihood of IUD initiation as a factor of level of cost-sharing, adjusting for cost-sharing for other methods, as well as age, region, employment status, and visits with an ob/gyn. This model accounts for clustering of individuals within plans. We calculated rates of IUD use for patient subgroups defined by each covariate, adjusted for all other covariates, by direct standardization under the regression model.20 Risk ratios for each covariate were estimated from the multivariate model. 21 Finally, we estimate the price elasticity for IUDs by modeling the change in the likelihood of selecting an IUD for each dollar increase in plan cost-sharing.

Results

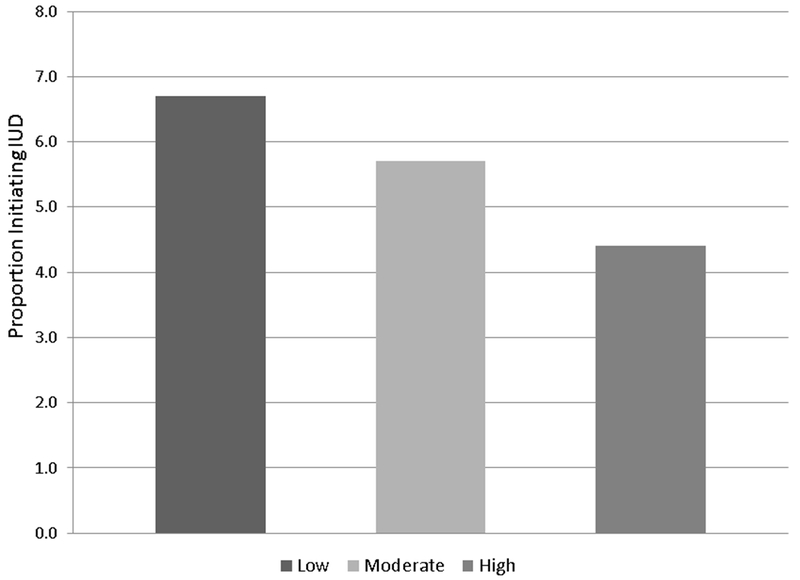

There were 1,682,425 women in our sample who were enrolled in plans that covered brand OCPs, generic OCPs, and IUDs and who submitted claims for one of these methods in 2011. Characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age among women with low, moderate or high levels of cost-sharing for IUDs. There were some regional differences between cost-sharing levels in our sample, although it is unclear whether this reflects geographic differences or differences in the plans represented in the MarketScan database. Generic OCPs were the most commonly used contraceptive methods (69.0%), followed by branded OCPs (25.5%). Rates of IUD initiation in 2011 were low at 5.5% overall, and IUD uptake declined as cost-sharing increased (Figure 1). The mean cost-sharing for IUD placement was $3.26 (SD:$3.86) among plans in the lowest quartile of IUD cost-sharing; $30.16 (SD:$16.77) among the 2nd and 3rd quartiles, and $161.56 (SD:$109.37) in the highest quartile (Table 1). Across all plans, the mean monthly costs for branded and generic OCPs ranged from $27-$31 and $9-$12, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women included in the study

| Patient and plan characteristics | All Plans | Plans with low levels of cost-sharing for IUDs* | Plans with moderate levels of cost-sharing for IUDs* | Plans with high levels of cost-sharing for IUDs* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of plans | N = 4,176 | N = 1,045 | N = 2,087 | N = 1,044 |

| Number of patients | 1,682,425 | N = 166,966 | N = 1,201,864 | N = 313,595 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 27.6 (8.1) | 27.3 (8.1) | 27.7 (8.1) | 27.5 (8.2) |

| Region (%) | ||||

| Northeast | 16.6 | 23.3 | 17.6 | 9.2 |

| Midwest | 24.4 | 26.1 | 23.9 | 25.6 |

| South | 39.5 | 21.2 | 43.3 | 35.0 |

| West | 17.4 | 28.3 | 12.8 | 29.0 |

| Unknown | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| Relationship of patient to employer (%) | ||||

| Employee | 47.0 | 44.0 | 48.0 | 44.7 |

| Spouse | 18.4 | 17.5 | 18.4 | 19.1 |

| Dependent | 34.6 | 38.5 | 33.7 | 36.2 |

| Visit to ob/gyn during study period (%) | 56.4 | 46.4 | 59.2 | 50.8 |

| First Contraceptive Method Used in Year - N (%) | ||||

| Branded Oral | 429,679 (25.5) | 36,985 (22.2) | 311,581 (25.9) | 80,737 (25.7) |

| Generic Oral | 1,161,328 (69.0) | 119,915 (71.8) | 821,455 (68.4) | 218,558 (69.7) |

| IUD | 93,237 (5.5) | 10,066 (6.0) | 68,828 (5.7) | 14,300 (4.6) |

| Out-of pocket costs for contraceptive methods | ||||

| OOP cost for IUD Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

$56.18 (83.19) $25.23 (59.88) |

$3.26 (3.86) $2.78 (6.64) |

$30.16 (16.77) $25.06 (26.74) |

$161.56 (109.37) $125.86 (98.00) |

| OOP cost for brand name OCPs Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

$28.38 (13.48) $26.49 (16.41) |

$27.16 (13.63) $25.52 (16.17) |

$27.82 (12.28) $26.26 (15.04) |

$30.58 (15.16) $28.40 (19.62) |

| OOP cost for generic OCPs Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

$10.20 (5.05) $9.72 (5.66) |

$9.68 (4.40) $9.49 (4.42) |

$9.85 (4.59) $9.72 (5.26) |

$11.46 (6.26) $10.01 (7.94) |

“Low” out of pocket costs correspond to costs in the lowest quartile; “moderate” correspond to costs in the second and third quartiles, and “high” correlate to costs in the highest quartile.

IUD=intrauterine device; OOP = out of pocket; OCP=oral contraceptive pill; SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range

Figure 1:

Intrauterine Device Initiation by Cost-Sharing Level

*“Low” out of pocket costs correspond to costs in the lowest quartile; “moderate” correspond to costs in the second and third quartiles, and “high” correlate to costs in the highest quartile.

* Adjusted for age, region, employment status, recent visit to an ob/gyn, and levels of cost sharing for OCPs.

Table 2 demonstrates correlation of cost-sharing of different contraceptive methods within plans. Levels of cost-sharing between IUDs and OCPs were poorly correlated (correlation coefficient:0.08 for branded OCPs and 0.13 for generic OCPs). Plans with lower cost-sharing for IUDs thus did not necessarily have lower levels of cost-sharing for OCPs. Cost-sharing for generic and brand OCPs was moderately correlated (correlation coefficient:0.56).

Table 2.

Correlation* between average copay within plans across different contraceptive methods

| IUD | Generic OCPs | Brand name OCPs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IUD | 1.0 | ||

| Generic OCPs | 0.13 | 1.0 | |

| Brand name OCPs | 0.08 | 0.56 | 1.0 |

Pearson correlation coefficients. All P<.001.

IUD=intrauterine device; OCP=oral contraceptive pill

In the multivariate model, the level of cost-sharing for IUDs was significantly associated with IUD initiation (Table 3). Among women enrolled in plans with the highest cost-sharing levels for IUDs, the adjusted IUD initiation rate was 4.4% versus 6.7% among women in plans with the lowest cost-sharing levels. Women in plans with the highest cost-sharing levels were 35% less likely to receive IUDs compared with women in plans with the lowest cost-sharing levels (adjusted Risk Ratio:0.65,95%CI:0.64,0.67). Women less than 20 years old were less likely to get an IUD than women aged 20-34 (RR:0.59;95%CI:0.57,0.62). Women who saw an ob/gyn in the study year were much more likely than women who did not to receive an IUD (RR:2.49;95%CI:2.45,2.53). The highest cost-sharing level for OCPs was associated with a small increased likelihood of IUD use, adjusting for other factors. Using the unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted models, we calculated a price elasticity for IUDs between −0.16% and −0.34% (unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted, respectively), indicating a −0.16% to −0.34% decline in demand for IUDs per dollar increase in IUD cost-sharing.22

Table 3.

Factors influencing the likelihood of IUD use among commercially insured women

| Adjusted proportion of women using IUDs (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) for IUD use | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost sharing for IUD | ||

| Low | 6.7 | Reference |

| Moderate | 5.7 | 0.85 (0.83, 0.87) |

| High | 4.4 | 0.65 (0.64, 0.67) |

| Age | ||

| <20 | 3.4 | 0.59 (0.57, 0.62) |

| 20-34 | 5.7 | Reference |

| ≥35 | 5.8 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 4.6 | Reference |

| Midwest | 5.2 | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) |

| South | 5.2 | 1.11 (1.09, 1.14) |

| West | 8.1 | 1.75 (1.72, 1.79 |

| Relationship of patient to employer | ||

| Employee | 5.6 | Reference |

| Spouse | 8.8 | 1.57 (1.54, 1.59) |

| Child | 2.7 | 0.48 (0.47, 0.49) |

| Visit with ob/gyn during 2011 | 7.3 | 2.49 (2.45, 2.53) |

| Level of cost sharing for branded OCPs | ||

| Low | 5.4 | Reference |

| Medium | 5.6 | 1.05 (1.0248, 1.07) |

| High | 5.5 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) |

| Level of cost-sharing for generic OCPs | ||

| Low | 5.5 | Reference |

| Medium | 5.1 | 0.93 (0.91, 0.94) |

| High | 6.3 | 1.14 (1.11, 1.16) |

Using generalized estimated equations with log-link and Poisson distribution, adjusting for age, region, employment status, recent visit to an ob/gyn, and levels of cost sharing for IUDs and OCPs.

IUD=intrauterine device; OCP=oral contraceptive pill;

Discussion

Our study shows that among women with employer-sponsored health insurance in the U.S., IUD initiation was higher when cost-sharing was lower, even after accounting for cost-sharing levels of other contraceptive methods under a given plan. Cost-sharing for contraception within individual plans was not well-correlated across methods, and higher cost-sharing for OCPs was only associated with a small increased IUD uptake. Although our data do not allow us to predict how women’s contraceptive use patterns will change when all contraceptive co-pays are eliminated, our findings are concordant with studies suggesting that when financial barriers are removed, women are more likely to use LARC methods for contraception. Additionally, our price sensitivity findings for IUDs are similar to those found for other prescription drug products.22 While it is generally more expensive to initiate an IUD or implant than a short-acting contraceptive method, over time, LARC methods (which can remain in place for 3-10 years) are far more cost-effective both in terms of medication costs and unintended pregnancies averted.23 By reducing women’s out-of-pocket costs and increasing LARC use, the ACA’s contraceptive mandate could entail health benefits for women and cost-savings for the health care system.

Importantly, however, even among plans with the lowest cost-sharing levels for IUDs (mean:$3.28), rates of IUD initiation among women in our sample were low. This was true even when the monthly out-of-pocket cost of OCPs was comparable to the one-time IUD initiation costs. The rates of IUD uptake in our study do underestimate the prevalence of IUD use among women using contraception in the health plans studied, since we were unable to capture women with IUDs placed pre-2011. However, the relatively low rates of IUD initiation even when IUDs were very inexpensive underscore that cost is not the only barrier to LARC use, and suggest that eliminating co-pays may be insufficient to increase uptake substantially. Inadequate counseling by providers, misconceptions held by patients and providers, device availability at office-based clinics, and many providers’ lack of training in IUD placement, are likely other important barriers that must be addressed for the ACA legislation to strongly impact use of these highly effective methods.3,18,24–29 In offering the full range of contraception to participants, the CHOICE study addressed barriers to access beyond cost, and this may have contributed to the very high rates of LARC use. In particular, primary care providers such as family practitioners place fewer IUDs and are often less comfortable doing so,28, 31 so that many patients seeking LARC are referred to other providers, particularly ob/gyns.24, 30 In our study, visits with an ob/gyn were strongly associated with IUD use. Training for other primary care providers thus may be particularly important for increasing access to IUDs and LARC more generally.

Limitations

Since our assessment of method use was based on insurance claims, we were able to analyze reimbursed expenses only and therefore we only included plan products with patients who used each method of interest during 2011. Patients in smaller plans or with fewer young women may thus be under-represented. In addition, we were unable to study women who paid out-of-plan for contraceptive methods. If many women self-paid for IUD insertions when their plans did not reimburse for this, we would have overestimated the impact of cost-sharing on method use. Additionally, this analysis focused on commercially-insured women and results may not generalize to publicly insured or uninsured individuals. Next, we had limited information about patient characteristics, and unmeasured confounders could influence method choice. Finally, there were relatively small differences in IUD initiation rates among patients with high versus low IUD cost-sharing (4.4% of patients with high cost-sharing and 6.7% of patients with low cost-sharing initiated IUDs), potentially reflecting the importance of other barriers to IUD use in this population.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that among commercially insured women in the U.S., the degree of cost-sharing appears to be associated with IUD use, and rates of IUD uptake are lowest among women with the highest co-pays. Elimination of cost-sharing under the ACA could play a role in increasing uptake of the most effective reversible contraceptive methods and reducing rates of unintended pregnancy in the U.S., particularly if implemented in combination with strategies to address other barriers to use.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Disclosures:

Dr. Pace’s effort was supported by the Global Women’s Health Fellowship, Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Dr. Dalton’s effort in part was supported by grant number 1 K08 JS015491 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Dalton is a Nexplanon Trainer for Merck. She also served on an advisory board for McNeil Consumer Healthcare.

No other authors have funding or conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Department of HHS. News Release: Affordable Care Act Ensures Women Receive Preventive Services at No Additional Cost. 2011. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/08/20110801b.html. Accessed March 18, 2013.

- 2.Dennis A, Grossman D. Barriers to Contraception and Interest In Over-the-Counter Access Among Low-Income Women: A Qualitative Study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. June 2012;44(2):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson KM, Speidel JJ, Saporta V, Waxman NJ, Harper CC. Contraceptive policies affect post-abortion provision of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. January 2011;83(1):41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost JJ. Trends in US women’s use of sexual and reproductive health care services, 1995–2002. Am J Public Health. October 2008;98(10):1814–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnusson BM, Sabik L, Chapman DA, et al. Contraceptive insurance mandates and consistent contraceptive use among privately insured women. Med Care. July 2012;50(7):562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleland K, Peipert JF, Westhoff C, Spear S, Trussell J. Family planning as a cost-saving preventive health service. N Engl J Med. May 5 2011;364(18):e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaffer ER, Sarfaty M, Ash AS. Contraceptive insurance mandates. Med Care. July 2012;50(7):559–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peipert JF, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstet Gynecol. December 2012;120(6):1291–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg D, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Cost as a Barrier to Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive (LARC) Use in Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. April 2013;52(4 Suppl):S59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. May 24 2012;366(21):1998–2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstock JR, Peipert JF, Madden T, Zhao Q, Secura GM. Continuation of reversible contraception in teenagers and young women. Obstet Gynecol. December 2012;120(6):1298–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatcher RA TJ, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D, ed Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York: Ardent Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. Oct 2012;98(4):893–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Macaluso M, Ouyang L, Kulczycki A, Grosse SD. Revival of the intrauterine device: increased insertions among US women with employer-sponsored insurance, 2002–2008. Contraception. February 2012;85(2):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dusetzina SB, Dalton VK, Chernew ME, Pace LE, Bowden G, Fendrick AM. Cost of contraceptive methods to privately insured women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. March 2013;23(2):e69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gariepy AM, Simon EJ, Patel DA, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB. The impact of out-of-pocket expense on IUD utilization among women with private insurance. Contraception. December 2011;84(6):e39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postlethwaite D, Trussell J, Zoolakis A, Shabear R, Petitti D. A comparison of contraceptive procurement pre- and post-benefit change. Contraception. November 2007;76(5):360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen RH, Goldberg AB, Grimes DA. Expanding access to intrauterine contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. November 2009;201(5):456 e451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. August 2010;203(2):115 e111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little RJA. Direct Standardization: A Tool for Teaching Linear Models for Unbalanced Data. The American Statistician. 1982;36(1):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. August 1 2005;162(3):199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chernew ME, Shah MR, Wegh A, et al. Impact of decreasing copayments on medication adherence within a disease management environment. Health Aff (Millwood). Jan-Feb 2008;27(1):103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J. Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. January 2009;79(1):5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akers AY, Gold MA, Borrero S, Santucci A, Schwarz EB. Providers’ perspectives on challenges to contraceptive counseling in primary care settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt). June 2010;19(6):1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Ruskin R, Steinauer J. Health care providers’ knowledge about contraceptive evidence: a barrier to quality family planning care? Contraception. April 2010;81(4):292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dehlendorf C, Ruskin R, Grumbach K, et al. Recommendations for intrauterine contraception: a randomized trial of the effects of patients’ race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Am J Obstet Gynecol. October 2010;203(4):319 e311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanwood NL, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. Obstetrician-gynecologists and the intrauterine device: a survey of attitudes and practice. Obstet Gynecol. February 2002;99(2):275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin SE, Fletcher J, Stein T, Segall-Gutierrez P, Gold M. Determinants of intrauterine contraception provision among US family physicians: a national survey of knowledge, attitudes and practice. Contraception. May 2011;83(5):472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harper CC, Blum M, de Bocanegra HT, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: the provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstet Gynecol. June 2008;111(6):1359–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC. Contraceptive methods available to patients of office-based physicians and title X clinics --- United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. January 14 2011;60(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landry DJ, Wei J, Frost JJ. Public and private providers’ involvement in improving their patients’ contraceptive use. Contraception. July 2008;78(1):42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]