Abstract

Background

Tobacco use is estimated to kill 7 million people a year. Nicotine is highly addictive, but surveys indicate that almost 70% of US and UK smokers would like to stop smoking. Although many smokers attempt to give up on their own, advice from a health professional increases the chances of quitting. As of 2016 there were 3.5 billion Internet users worldwide, making the Internet a potential platform to help people quit smoking.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of Internet‐based interventions for smoking cessation, whether intervention effectiveness is altered by tailoring or interactive features, and if there is a difference in effectiveness between adolescents, young adults, and adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register, which included searches of MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO (through OVID). There were no restrictions placed on language, publication status or publication date. The most recent search was conducted in August 2016.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Participants were people who smoked, with no exclusions based on age, gender, ethnicity, language or health status. Any type of Internet intervention was eligible. The comparison condition could be a no‐intervention control, a different Internet intervention, or a non‐Internet intervention. To be included, studies must have measured smoking cessation at four weeks or longer.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed and extracted data. We extracted and, where appropriate, pooled smoking cessation outcomes of six‐month follow‐up or more, reporting short‐term outcomes narratively where longer‐term outcomes were not available. We reported study effects as a risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

We grouped studies according to whether they (1) compared an Internet intervention with a non‐active control arm (e.g. printed self‐help guides), (2) compared an Internet intervention with an active control arm (e.g. face‐to‐face counselling), (3) evaluated the addition of behavioural support to an Internet programme, or (4) compared one Internet intervention with another. Where appropriate we grouped studies by age.

Main results

We identified 67 RCTs, including data from over 110,000 participants. We pooled data from 35,969 participants.

There were only four RCTs conducted in adolescence or young adults that were eligible for meta‐analysis.

Results for trials in adults: Eight trials compared a tailored and interactive Internet intervention to a non‐active control. Pooled results demonstrated an effect in favour of the intervention (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.30, n = 6786). However, statistical heterogeneity was high (I2 = 58%) and was unexplained, and the overall quality of evidence was low according to GRADE. Five trials compared an Internet intervention to an active control. The pooled effect estimate favoured the control group, but crossed the null (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.09, n = 3806, I2 = 0%); GRADE quality rating was moderate. Five studies evaluated an Internet programme plus behavioural support compared to a non‐active control (n = 2334). Pooled, these studies indicated a positive effect of the intervention (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.18). Although statistical heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 60%) and was unexplained, the GRADE rating was moderate. Four studies evaluated the Internet plus behavioural support compared to active control. None of the studies detected a difference between trial arms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.18, n = 2769, I2 = 0%); GRADE rating was moderate. Seven studies compared an interactive or tailored Internet intervention, or both, to an Internet intervention that was not tailored/interactive. Pooled results favoured the interactive or tailored programme, but the estimate crossed the null (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.22, n = 14,623, I2 = 0%); GRADE rating was moderate. Three studies compared tailored with non‐tailored Internet‐based messages, compared to non‐tailored messages. The tailored messages produced higher cessation rates compared to control, but the estimate was not precise (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.41, n = 4040), and there was evidence of unexplained substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 57%); GRADE rating was low.

Results should be interpreted with caution as we judged some of the included studies to be at high risk of bias.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence from trials in adults suggests that interactive and tailored Internet‐based interventions with or without additional behavioural support are moderately more effective than non‐active controls at six months or longer, but there was no evidence that these interventions were better than other active smoking treatments. However some of the studies were at high risk of bias, and there was evidence of substantial statistical heterogeneity. Treatment effectiveness in younger people is unknown.

Plain language summary

Can Internet‐based interventions help people to stop smoking?

Background

Tobacco use is estimated to kill 7 million people a year. Nicotine is highly addictive, but surveys indicate that almost 70% of US and UK smokers would like to stop smoking. Although many smokers attempt to give up on their own, advice from a health professional increases the chances of quitting. As of 2016 there were 3.5 billion Internet users worldwide. The Internet is an attractive platform to help people quit smoking because of low costs per user, and it has potential to reach smokers who might not access support because of limited health care availability or stigmatisation. Internet‐based interventions could also be used to target young people who smoke, or others who may not seek traditional methods of smoking treatment.

Study Characteristics

Up to August 2016, this review found 67 trials, including data from over 110,000 participants. Smoking cessation data after six months or more were available for 35,969 participants. We examined a range of Internet interventions, from a low intensity intervention, for example providing participants with a list of websites for smoking cessation, to intensive interventions consisting of Internet‐, email‐ and mobile phone‐delivered components. We classed interventions as tailored or interactive, or both. Tailored Internet interventions differed in the amount of tailoring, from multimedia components to personalised message sources. Some interventions also included Internet‐based counselling or support from nurses, peer coaches or tobacco treatment specialists. Recent trials incorporated online social networks, such as Facebook, Twitter, and other online forums.

Key results

In combined results, Internet programmes that were interactive and tailored to individual responses led to higher quit rates than usual care or written self‐help at six months or longer.

Quality of evidence

There were not many trials conducted in younger people. More trials are needed to determine the effect on Internet‐based methods to aid quitting in youth and young adults. Results should be interpreted with caution, as we rated some of the included studies at high risk of bias, and for most outcomes the quality of evidence was moderate or low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Internet‐based interventions for adults who want to stop smoking.

| Internet‐based interventions for adults who want to stop smoking | |||||

| Patient or population: adults who want to stop smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Internet‐based interventions | |||||

| Outcomes1 | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with Comparator | Risk with Internet‐based interventions | ||||

| Interactive and tailored versus non‐active control Self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 12 months | 129 per 1000 | 148 per 1000 (130 to 167) | RR 1.15 (1.01 to 1.30) | 6786 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2, 3 |

| Internet versus active control Self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 12 months | 129 per 1000 | 118 per 1000 (100 to 140) | RR 0.92 (0.78 to 1.09) | 3806 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 |

| Internet plus behavioural support versus non‐Internet‐based non‐active control Self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 12 months | 78 per 1000 | 131 per 1000 (101 to 169) | RR 1.69 (1.30 to 2.18) | 2334 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 5 |

| Internet plus behavioural support versus non‐Internet‐based active control Self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 7 months | 157 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (132 to 186) | RR 1.00 (0.84 to 1.18) | 2769 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 6 |

| Comparisons between Internet interventions (programmes): tailored/interactive versus not tailored/interactive Self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 12 months | 99 per 1000 | 109 per 1000 (98 to 121) | RR 1.10 (0.99 to 1.22) | 14,623 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 |

| Comparisons between Internet interventions (messages): tailored/interactive versus not tailored/interactive Self‐reported smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6 months | 90 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (88 to 128) | RR 1.17 (0.97 to 1.41) | 4040 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 8, 9 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1For all, outcome of interest is smoking cessation. Each row represents a different comparison.

2Downgraded one level for risk of bias: High risk of bias in one or more domains for most (five) studies. 3Downgraded one level for inconsistency: Moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 53%). 4Downgraded one level for risk of bias: Unclear or high risk of bias for one or more domains for most (three) studies. 5Downgraded one level for inconsistency: Moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 60%). 6Downgraded one level for risk of bias: Unclear risk of bias for two domains in two studies. 7Downgraded one level for risk of bias: High risk of attrition bias in two studies. 8Downgraded one level for inconsistency: Moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 57%).

Background

Worldwide, tobacco smoking is the primary cause of preventable premature disease and death. Tobacco use is estimated to kill 7 million people a year. If current trends continue, by 2030 tobacco will contribute to the deaths of more than eight million people a year, with 80% of those deaths predicted to occur in the developing world (WHO 2017). People who smoke are more prone to developing various types of cancer, such as those of the oral cavity, larynx, bladder and particularly of the lung. Tobacco smokers are also at substantially increased risk of developing heart disease, stroke, emphysema and other fatal diseases (WHO 2004; Surgeon General 2014). Additionally, passive smoking is associated with serious morbidity (SCTH 1998; Surgeon General 2006). Smoking imposes a huge economic burden on society; maximising the delivery of smoking cessation interventions can achieve more in terms of years of life saved and economic benefits than most medical interventions for smoking‐related illnesses (Coleman 2004). To reduce the growing global burden of tobacco‐related mortality and morbidity, and the impact of tobacco use on economic indicators, tobacco control has become a worldwide public health imperative (WHO 2004).

Prevention and cessation are the two principal strategies in the battle against tobacco smoking. Nicotine is highly addictive (Benowitz 2010), but recent surveys indicate that almost 70% of US and UK smokers would like to stop smoking (Lader 2009; MMWR 2011). Although many smokers attempt to give up on their own, advice from a health professional increases quit attempts and increases the use of effective medications which can nearly double or triple rates of successful cessation (Fiore 2008).

There is good evidence for the effectiveness of brief, therapist‐delivered interventions, such as advice from a physician (Stead 2013a) in helping people to quit smoking. There appears to be additional benefit from more intensive behavioural interventions, such as group therapy (Stead 2017), individual counselling (Lancaster 2017) and telephone counselling (Stead 2013b). However, these more intensive therapies are usually dependent on a trained professional delivering or facilitating the interventions. This is both expensive and time‐consuming for the health providers, and often inconvenient to the recipient, because of lengthy waiting times and the need to take time off work. Another major limitation of these more intensive interventions is that they reach only a small proportion of those who smoke.

Potential benefits of Internet‐based interventions

It is estimated that in 2016 there were 3.5 billion Internet users worldwide (ICT 2016). The Internet has the potential to deliver behaviour change interventions (Japuntich 2006; Strecher 2006; Swartz 2006; Graham 2007). Internet‐based material is an attractive intervention platform, because of low costs for the user, resulting in high cost effectiveness for clinically‐effective interventions (Swartz 2006). Additionally, non‐consumable interventions, such as automated self‐help Internet interventions, are less expensive when delivered on a large scale (Muñoz 2012b). The Internet can be accessed in people's homes, on smart phones, in public libraries and through other public access points, such as Internet cafes and information kiosks, and is available all day every day, even in areas where there are not the resources for a smoking cessation clinic (e.g. some rural or deprived areas and low‐income countries). Internet programmes can also be highly tailored to mimic the individualisation of one‐to‐one counselling. Online treatment programmes also offer a greater level of anonymity than in‐person or phone‐based counselling, and have the potential to reach audiences who might not otherwise seek support because of limited healthcare provision or possible stigmatisation. There is some evidence suggesting that quit rates obtained by using Internet interventions for smoking cessation are comparable with quit rates reported from smoking cessation therapies or smoking cessation groups which may be more costly in terms of money, time or both (Muñoz 2012b). Internet use by young people has grown exponentially and has a powerful role in influencing youth culture, and may therefore be more effective in reaching a target population of young people who smoke than the more traditional providers. A recent review concluded that Internet use may be an effective tool for tobacco treatment interventions with college students, many of whom may not identify themselves as smokers or seek traditional methods of treatment (Brown 2013).

Potential limitations of Internet‐based interventions

Using the Internet for smoking cessation programmes may also have limitations. There are a large number of smoking cessation websites, but they do not all provide a direct intervention. Some studies of popular smoking cessation websites and their quality suggest that smokers seeking tobacco dependence treatment online may have difficulty discriminating between the many sites available (Bock 2004; Etter 2006b). In addition, websites that provide direct treatment often do not fully implement treatment guidelines and do not take full advantage of the interactive and tailoring capabilities of the Internet (Bock 2004). Furthermore, a study on rates and determinants of repeat participation in a web‐based health behaviour change programme suggested that such programmes may reach those who need them the least. For example, older individuals who had never smoked were more likely to participate repeatedly than those who currently smoke (Verheijden 2007). The Internet is also less likely to be used by people with lower incomes, who are more likely to smoke (Eysenbach 2007; Kontos 2007), and less accessed by older people (ONS 2016).

Previous version of this review

The first version of this review was published in the Cochrane Library in 2010 (Civljak 2010). The 2010 version included 20 studies, 10 of which compared an Internet‐based intervention to a non‐Internet‐based intervention or to a usual‐care control, and 10 of which compared two or more Internet‐based interventions. Due to clinical and statistical heterogeneity between the included studies, we did not conduct any meta‐analyses in the original review. Results suggested that some Internet‐based interventions can assist smoking cessation, especially where the intervention was tailored and interactive, but trials did not show consistent effects.

The second version of this review was published in 2013 (Civljak 2013), and identified 28 studies. Fifteen of these compared an active Internet intervention with a non‐Internet arm and 14 compared two Internet interventions (i.e. one study contributed to both categories); 18 were included in the meta‐analysis. All included studies were RCTs, with the exception of one study, which was quasi‐randomised (Haug 2011). We also found 13 potentially relevant ongoing or unpublished trials.

Objectives

To determine:

The effectiveness of Internet‐based interventions for smoking cessation;

Whether intervention effectiveness is altered by tailoring or interactive features;

If there is a difference in effectiveness between adolescents, young adults, and adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Examples of quasi‐random methods of assignment include alternation, date of birth, and medical record number. There were no restrictions by language.

Types of participants

Current smokers, with no exclusions by age, gender, ethnicity, language spoken or health status. We analyse studies in adolescents and young adults separately from the studies in adults, as both subgroups have particular needs which warrant separate investigation.

Types of interventions

We included studies evaluating Internet interventions in all settings and from all types of providers. There was no exclusion by intervention method or duration. We included trials where the Internet intervention was evaluated with an additional behavioural intervention/support component, or delivered alongside pharmacotherapy such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion or varenicline. The trials compared different types and combinations of intervention. The trials compared Internet‐based programmes to no treatment or to other forms of treatment, such as self‐help booklets. We included trials of interactive, tailored and non‐interactive interventions that focused on standard approaches to information delivery. Interactive interventions were not necessarily personalised. We defined tailored interventions as programmes that were adapted to a participant's characteristics, and interactive interventions as those which involved a two‐way flow of information between the Internet and the participant.

Personalised interventions can vary considerably, from minimal personalisation to those which have been developed based on theoretical models relevant to desired treatment outcomes, such as self‐efficacy. The interventions used in each study were fully described, illustrating the heterogeneity of the interventions (e.g. in relation to varying content, intensity, number of sessions, and duration of contact time).

We excluded trials that used the Internet solely for recruitment and not for delivery of smoking cessation treatment. We also excluded trials where Internet‐based programmes were used to remind participants of appointments for treatment that is not conducted online (e.g. face‐to‐face counselling, or pharmacotherapy). Text messaging, and smart‐phone application interventions are covered in a Cochrane Review of mobile phone interventions (Whittaker 2016), and a review of video‐based interventions is currently in progress with the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group (Tzelepis 2017). We therefore do not address these interventions in this review.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome is smoking cessation at least six months after the start of the intervention, and longer wherever the data were available. Where studies did not have follow‐up of six months or longer, we report shorter‐term outcomes narratively. We excluded trials with less than four weeks follow‐up.We preferred sustained or prolonged cessation over point prevalence abstinence, but did not exclude studies which only reported the latter. We included studies that relied on self‐reported cessation, as well as those that required biochemical validation of abstinence, but preferred biochemically‐validated rates where available.

Where reported, we extracted data on user satisfaction rates, intervention costs, adverse outcomes, use of the Internet site or programme use, self‐efficacy, use of NRT or other pharmacotherapies, reductions in the number of cigarettes or in smoking frequency, and the impact of Internet programme completion on smoking cessation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic Searches

We searched the specialised register of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group for records including the terms 'Internet' or 'www*' or 'web' or 'net' or 'online' , in the title, abstract or as keywords. The most recent search of the register was 23rd August 2016. At the time of the search the register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), issue 7, 2016; MEDLINE (through OVID) to update 20160729; Embase (through OVID) to week 201632; PsycINFO (through OVID) to update 20160725. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched. We also searched clinicaltrials.gov for records of relevant completed or ongoing studies.

Other Sources We searched the reference lists of identified studies for other potentially relevant trials, and contacted authors and experts in this field for unpublished work.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed potentially relevant papers for inclusion, resolving disagreements through discussion, with each review author writing their reasons for inclusion/exclusion until a consensus was reached, and where necessary by consulting a third party. We noted reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

For this update, the extraction workload was split between three review authors (GT, MD, MS). Two review authors independently extracted data, and one extractor then checked data and compared the findings. This stage included an evaluation of risks of bias (see below). We contacted study authors where outcome data were missing.

We extracted the following information from each trial:

Country and setting;

Method of selection of participants;

Study dates;

Definition of smoker used;

Population type (e.g. college students, people with chronic conditions);

Methods of randomisation (sequence generation and allocation concealment);

Demographic characteristics of participants (e.g. average age, gender, average cigarettes/day);

Intervention and control description (i.e. provider, material delivered, control intervention if any, duration, level of interactivity, etc.);

Outcomes including definition of abstinence used, and whether cessation was biochemically validated;

Proportion of participants with follow‐up data;

Any harms or adverse effects;

Sources of funding;

Conflicts of interest.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risks of bias for each study, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011) for each study according to the presence and quality of the randomisation process, concealment of allocation, and description of withdrawals and dropouts.

Measures of treatment effect

We produced a risk ratio (RR) for the outcome for each trial, calculated as: (number who stopped smoking in the intervention group/total number randomised to the intervention group)/(number who stopped smoking in the control group/total number randomised to the control group). A risk ratio greater than one indicates that more people stopped smoking in the intervention group than in the control group. We displayed risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals in forest plots.

We conducted an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, meaning that we include all those randomised to their original groups, whether or not they remained in the study. We treated dropouts or those lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered clinical, statistical and methodological heterogeneity. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which assesses the proportion of the variation between studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2003). Values over 50% suggest substantial heterogeneity, but its significance also depends upon the magnitude and direction of the effect and the strength of the evidence (as estimated by the confidence interval).

Data synthesis

We separated trials in adolescents from those in young adults and older adults. We distinguished between tailored or interactive and non‐tailored, non‐interactive interventions. In the five comparisons for which we judged meta‐analysis to be appropriate, we pooled the weighted average of risk ratios, using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model, with a 95% confidence interval. Where there were 10 or more of studies we planned to use funnel plots to help identify possible publication bias, but there were not enough studies reporting any individual outcome for us to do this.

Sensitivity analysis

We used sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of using data from complete cases (i.e. including only participants who were followed up) as compared to our primary ITT analysis which assumes that those who dropped out or who were lost to follow‐up were continuing smokers.

Summary of findings table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for self‐report or bio‐verified smoking cessation at 6‐months follow‐up or longer, and to draw conclusions about the quality of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

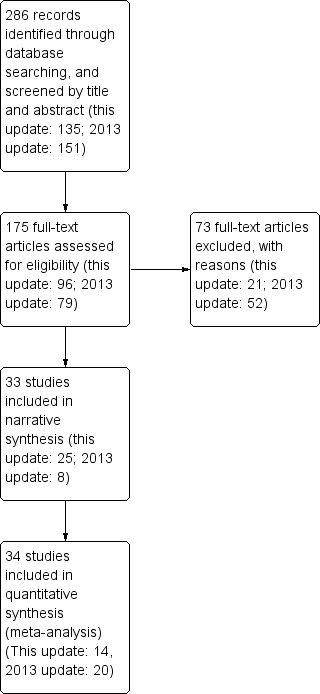

Across the updates we found 286 potentially relevant records through database searching, and screened them by title and abstract (this update: 135; 2013 update: 151). Some studies were spread across more than one record. We assessed 177 full‐text articles for eligibility (this update: 97; 2013 update: 80). We excluded 73 full‐text articles, with reasons (this update: 21; 2013 update: 52). A full list of these studies along with reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Sixty‐seven studies met the inclusion criteria, with 33 of them included in narrative synthesis (this update: 25; 2013 update: 8), and 34 studies were included in quantitative synthesis (meta‐analysis) (this update: 14; 2013 update: 20). Our review now includes data from over 110,000 participants, of whom 35,969 were included in the meta‐analysis. Four studies were cluster‐randomised, and one was quasi‐randomised (Haug 2011).

The Characteristics of included studies table provides further detail and 'Risk of bias' assessments for each included study. See Figure 1 for flow chart of records.

1.

Study flow diagram. Please note that in some cases more than one article was attributable to the same study.

Recruitment and participants

Most studies were conducted in the USA and participants were therefore recruited from that population. Eleven trials were conducted in the Netherlands, five in the UK, one in the Republic of Ireland, three in Australia, two in Norway, two in Switzerland, three in Germany, one in England, one in Belgium, one in Denmark, one in Spain, one in China, and one across the USA and Canada. The studies by Muñoz and colleagues recruited from multiple countries.

In most of the studies recruitment was web‐based, with participants finding the sites through search engines and browsing. Several trials used press releases, billboards, television advertisements and flyers in addition to web‐based recruitment. As a result of these recruitment methods, participants included in these trials were motivated to quit smoking, and chose the Internet as a tool for smoking cessation support. Nineteen studies recruited smokers from healthcare settings: Clark 2004 recruited people undergoing chest computerised tomography as a screening assessment for lung cancer at their first follow‐up visits; Strecher 2008 recruited members of two health management organisations (HMOs); Swan 2010 recruited participants from a large healthcare organisation; Schulz 2014 recruited through health authorities; McClure 2014 identified people from automated healthcare records and invited participants by letter; Haug 2011 recruited participants from three German inpatient rehabilitation centres; Humfleet 2013 recruited participants from three clinics serving people with HIV; Burford 2013 recruited participants from pharmacies when presenting to collect prescriptions or purchase over‐the‐counter medications; Frederix 2015 recruited participants from cardiology departments; Harrington 2016 recruited from hospitals; two studies recruited participants from a Military Veteran Medical Centres (Dezee 2013; Calhoun 2016); Borland 2013 recruited participants during phone calls to national quit lines; Emmons 2013 recruited participants from cancer treatment centres and through websites; seven studies recruited participants from primary care settings (Dickinson 2013; Mehring 2014; Zullig 2014; Houston 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; McClure 2016; Smit 2016); Voncken‐Brewster 2015 recruited through primary care and an online panel. Six studies recruited from other settings: McDonnell 2011 recruited online, sponsored links based on search terms entered into Yahoo or Google, flyers, word of mouth, a press conference, email campaign and a local television campaign; Oenema 2008 recruited from a pool of people registered with an online research agency, including non‐smokers and smokers who were not necessarily motivated to quit at baseline; Skov‐Ettrup 2016 recruited participants from two Danish health surveys; and Bannink 2014 recruited participants from educational institutions. Choi 2014 recruited employees during a regularly scheduled training session. No information was available for one study (Mananes 2014), and In Yang 2016 the source of participants was not clear.

This review includes over 110,000 participants, and 35,969 were included in the meta‐analysis. Most studies recruited a full adult age range, three studies recruited adolescents only (Patten 2006; Woodruff 2007; Bannink 2014), and seven studies recruited young adults, university or college students (An 2008; Simmons 2011; Berg 2014; Emmons 2013; An 2013; Epton 2014; Cameron 2015;). One study recruited adult participants who were childhood cancer survivors (Emmons 2013). Two studies recruited only Korean Americans (McDonnell 2011; Moskowitz 2016). Two studies recruited military veterans, or their families (Dezee 2013; Calhoun 2016). Four studies recruited participants with chronic physical conditions (Zullig 2014; Frederix 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; Yang 2016), and one study recruited hospitalised patients (Harrington 2016). One study recruited pregnant smokers (Herbec 2014). Sample sizes ranged from fewer than 70 (McClure 2016) to nearly 12,000 (Etter 2005). There were more women than men (see Characteristics of included studies) and the mean age ranged from 16 years (Patten 2006; Woodruff 2007; Bannink 2014) to 63 years (Zullig 2014). In 21 studies, participants were offered financial compensation for completing assessment surveys or biochemical analysis (Muñoz 2006 Study 3; Muñoz 2006 Study 4; Woodruff 2007; An 2008; Oenema 2008; Te Poel 2009; Graham 2011; McDonnell 2011; Bricker 2013; Berg 2014; Brown 2014; Fraser 2014; Mehring 2014; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; Choi 2014; Harrington 2016; Calhoun 2016; Cobb 2016; McClure 2016; Moskowitz 2016; Smit 2016). In four studies, the participants could enter a draw to win prizes (Wangberg 2011; Elfeddali 2012; Stanczyk 2014; Borland 2015), and in four studies participants were offered financial compensation and entered into a prize draw (An 2013; Epton 2014; McClure 2014; Cameron 2015).

Interventions

A range of Internet interventions were tested in the included studies, from a very low intensity intervention providing a list of websites for smoking cessation (Clark 2004), to highly intensive interventions consisting of Internet‐, email‐ and mobile phone‐delivered components (Brendryen 2008a; Brendryen 2008b; Borland 2013). Tailored Internet interventions differed in the amount of tailoring, from a bulletin board facility (Stoddard 2008), a multimedia component (McKay 2008), tailored and personalised access (Strecher 2005; Rabius 2008; Wangberg 2011) to very high‐depth tailored stories and highly personalised message sources (Strecher 2008). Some trials also included counselling or support from nurses (Bannink 2014; Choi 2014; Smit 2016), peer coaches (An 2013) or tobacco treatment specialists (Houston 2015). Recent trials have also incorporated online social networks, such as Facebook (Cobb 2016), Twitter (Pechmann 2016), and WeChat (Yang 2016), and online forums (Dickinson 2013), chat rooms (Calhoun 2016), and support groups (Houston 2015). Two interventions were very distinct from the rest. In addition to brief smoking advice, Burford 2013 used an Internet‐based three‐dimensional face age progression simulation software package to create a stream of aged images of faces from a standard digital photograph. The resulting aged image was adjusted to compare how the participant aged as a smoker versus as a non‐smoker. In Wittekind 2015, the authors used an online version of the approach‐avoidance task, where participants used the computer mouse to pull (i.e. approach, leading to an enlarged picture) or push (i.e. avoid, leading to a reduced picture) neutral or smoking‐related pictures.

We also identified nine trials of lifestyle interventions that included a smoking cessation component. These interventions included content on a range of topics, including diet and healthy eating, physical activity and fitness, alcohol and drug use, sexual behaviour, unpleasant sexual experiences, bullying, mental health, patient‐provider relationships, and medication management (Oenema 2008; Dickinson 2013; Bannink 2014; Epton 2014; Schulz 2014; Zullig 2014; Cameron 2015; Frederix 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015).

More details are given in the comparisons section below, and descriptions of the main features of each study intervention are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

Cessation

Forty‐nine studies reported smoking status at least six months after the start of the intervention; the remaining 18 studies followed participants for less than six months (Etter 2005; Strecher 2005; Swartz 2006; Oenema 2008; Stoddard 2008; An 2013; Bricker 2013; Dezee 2013; Bannink 2014; Berg 2014; Herbec 2014; Mananes 2014; Mehring 2014; Shuter 2014; Zullig 2014; Wittekind 2015; Cobb 2016; Pechmann 2016).

Studies reported a range of definitions of abstinence at the time of follow‐up. Where studies reported abstinence rates for more than one definition we displayed the effect using the most conservative outcome (with the exception of An 2008, see below). For 21 studies, seven‐day smoking abstinence was the main outcome measure (Clark 2004; Japuntich 2006; Muñoz 2006 Study 3; Muñoz 2006 Study 4; Swartz 2006; McKay 2008; Stoddard 2008; Strecher 2008; Humfleet 2013; Muñoz 2009; Te Poel 2009; McDonnell 2011; Haug 2011; Wangberg 2011; Choi 2014; Fraser 2014; Shuter 2014; Houston 2015; Calhoun 2016; Cobb 2016; McClure 2016). Ten studies reported 30‐day self‐reported smoking abstinence (Patten 2006; Swan 2010; McDonnell 2011; Graham 2011; Simmons 2011; Emmons 2013; McClure 2014; Harrington 2016; Mavrot 2016; Moskowitz 2016). Mason 2012 reported three‐month prolonged abstinence at six months from baseline. Borland 2015, Stanczyk 2014, and Yang 2016 reported sustained abstinence at six months, while Borland 2013 and Brown 2014 reported six‐month sustained abstinence at seven‐month follow‐up. Bolman 2015 reported five‐month continuous abstinence at six‐month follow‐up (allowing a one‐month grace period) and Smit 2016 reported six‐month prolonged abstinence at 12‐month follow‐up. Elfeddali 2012 and Skov‐Ettrup 2016 reported continuous 12‐month abstinence. An 2008 assessed six‐month prolonged abstinence from smoking; this study also reported seven‐day and 30‐day prevalence abstinence. We used 30‐day rates as our primary outcome, because the programme did not involve setting a quit date, and the prolonged abstinence was based on self‐report of time since last cigarette rather than repeated assessments of abstinence.

Six of the 18 short‐term studies assessed self‐reported point prevalence abstinence at three‐month follow‐up only (Etter 2005; Swartz 2006; Stoddard 2008; Bricker 2013; Dezee 2013; Mananes 2014). Shuter 2014 reported biochemically‐verified point prevalence abstinence at three‐month follow‐up, Pechmann 2016 reported sustained abstinence at two‐month follow‐up, and Mehring 2014 reported continuous cessation at 12 weeks. An 2013 and Berg 2014 reported 30‐day prolonged abstinence at 12 weeks whilst Strecher 2005 assessed 28‐day continuous abstinence rates at six‐week follow‐up, and 10‐week continuous abstinence rates at 12‐week follow‐up. Herbec 2014 assessed four‐week continuous abstinence whilst Wittekind 2015 and Burford 2013 assessed point prevalence at four weeks and six months, respectively. In one study, seven‐day smoking abstinence was a secondary outcome, while time spent on the website, use of pages, cessation aids used in the past and during the study period were the main outcome measures (Stoddard 2008).

Finally, there were nine trials of lifestyle interventions that included a smoking cessation component. Zullig 2014 and Bannink 2014 assessed point prevalence abstinence at three and four months, respectively. Three studies assessed sustained cessation at six months (Epton 2014; Cameron 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015). Oenema 2008 measured smoking behaviour at one month, Frederix 2015 at 24 weeks, Dickinson 2013 at six months, and Schulz 2014 at 24 months, but the authors did not specify what measure of smoking cessation was used.

Due to the limited face‐to‐face contact and to data collection through Internet or telephone interviews, biochemical validation to confirm self‐reported smoking abstinence was conducted in only 18 trials. Nine measured carbon monoxide (CO) in expired air (Clark 2004; Japuntich 2006; Patten 2006; An 2008; Simmons 2011; Burford 2013; Dezee 2013; Humfleet 2013; Shuter 2014), five measured salivary cotinine (Elfeddali 2012; Harrington 2016; Brown 2014; Calhoun 2016; Smit 2016), two measured urinary cotinine (Choi 2014; Mehring 2014) and two measured nicotine and hair cotinine (Epton 2014; Cameron 2015). As Harrington 2016 only biochemically verified abstinence among a subset of self‐reported abstainers at follow‐up, we used self‐reported rates rather than validated rates.

Other outcomes

User satisfaction was measured in 21 studies (Strecher 2005; Woodruff 2007; Stoddard 2008; Muñoz 2009; Te Poel 2009; Choi 2014; Bricker 2013; Emmons 2013; Bannink 2014; Berg 2014; Brown 2014; Fraser 2014; Mananes 2014; Schulz 2014; Shuter 2014; Stanczyk 2014; Bolman 2015; Frederix 2015; Wittekind 2015; Harrington 2016; McClure 2016). Intervention cost was reported in eight studies (Etter 2005; Rabius 2008; Borland 2013; Burford 2013; Mehring 2014; Calhoun 2016; Harrington 2016; Skov‐Ettrup 2016). Few studies reported adverse events. Borland 2013 reported one case of hospitalisation at one month, while Frederix 2015 reported a new pathology in one intervention participant lost to follow‐up. Mehring 2014 reported that 26 participants experienced adverse events. In the intervention group, four participants reported weight gain, two participants reported increased perceived stress, one participant had a sleep disorder, and one participant had increased irritability. In the usual‐care group, six participants had increased perceived stress, five participants had cardiovascular problems, four participants reported fatigue, four participants reported weight gain, two participants had sweating, one participant had a sleep disorder, and one participant specified increased irritability. Three other studies reported adverse events but the interventions in these studies included smoking cessation medicines (Dezee 2013; McClure 2016; Yang 2016). Use of the Internet site or programme use was measured in 40 studies (Clark 2004; Japuntich 2006; Swartz 2006; Brendryen 2008b; McKay 2008; Oenema 2008; Rabius 2008; Strecher 2008; Muñoz 2009; Swan 2010; McDonnell 2011; Wangberg 2011; Borland 2013; An 2013; Bricker 2013; Dickinson 2013; Emmons 2013; Berg 2014; Brown 2014; Choi 2014; Epton 2014; Fraser 2014; Herbec 2014; Mananes 2014; McClure 2014; Schulz 2014; Shuter 2014; Zullig 2014; Borland 2015; Cameron 2015; Houston 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; Calhoun 2016; Cobb 2016; Harrington 2016; Mavrot 2016; McClure 2016; Moskowitz 2016; Skov‐Ettrup 2016; Pechmann 2016). Smoking cessation self‐efficacy was measured in 16 trials (Haug 2011; Wangberg 2011; Emmons 2013; Choi 2014; Epton 2014; McClure 2014; Schulz 2014; Shuter 2014; Stanczyk 2014; Bolman 2015; Cameron 2015; Calhoun 2016; Harrington 2016; Mavrot 2016; Moskowitz 2016; Skov‐Ettrup 2016). Use of NRT or other pharmacotherapies was a secondary outcome measure in 12 trials (Patten 2006; Brendryen 2008b; McKay 2008; Strecher 2008; Swan 2010; Borland 2013; Emmons 2013; McClure 2014; Mehring 2014; Borland 2015; Harrington 2016; Mavrot 2016). Eleven studies assessed reductions in the number of cigarettes or in smoking frequency as secondary outcomes (Patten 2006; Woodruff 2007; Choi 2014; Berg 2014; Epton 2014; Mananes 2014; Mehring 2014; Cameron 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; Wittekind 2015; Harrington 2016;). McDonnell 2011, Elfeddali 2012, Berg 2014, Mananes 2014, Shuter 2014, Zullig 2014, Voncken‐Brewster 2015, and Moskowitz 2016 also reported the impact of Internet programme completion on smoking cessation.

Comparisons

In this update, we have grouped studies according to whether they (1) compared an Internet intervention with a non‐active control arm (e.g. printed self‐help guides or usual care); (2) compared an Internet intervention with an active control arm (e.g. telephone or face‐to‐face counselling); (3) evaluated the addition of an Internet programme plus behavioural support; or (4) compared one Internet intervention to another. Where data were available, we grouped analyses by age (i.e. adults, young adults, adolescents). We treated printed self‐help materials as a non‐active control since the effect of these is typically small, although tailored materials may have more effect (Hartman‐Boyce 2014). In 15 trials, all participants were using, or were offered, pharmacotherapy (Strecher 2005; Japuntich 2006; Brendryen 2008a; Brendryen 2008b; Strecher 2008; Swan 2010; Dezee 2013; Emmons 2013; Choi 2014; Fraser 2014; Shuter 2014; Calhoun 2016; McClure 2016; Pechmann 2016; Yang 2016) and the Internet component was thus being evaluated as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy. We grouped these in comparisons based on the nature of the Internet component and the control. There were two exceptions to this: (1) Yang 2016 compared three trial arms, and one of these was not prescribed smoking cessation medication; and (2) Fraser 2014 compared variations in intervention components in which five intervention components were either "turned on or off"; one of these components was NRT, and therefore not all arms received NRT. Fraser 2014 was not eligible for meta‐analysis.

One study contributed to three comparisons (Borland 2013), and three studies each contributed to two comparisons (Simmons 2011; Skov‐Ettrup 2016; Smit 2016).

Please note that we did not include data from lifestyle interventions in the meta‐analysis, as data for smokers only were not available.

Internet intervention compared to non‐active control

Twenty‐one trials compared an Internet intervention to a non‐active control (Clark 2004; Swartz 2006; Woodruff 2007; An 2008; Oenema 2008; McDonnell 2011; Haug 2011; Elfeddali 2012; Borland 2013; Emmons 2013; Humfleet 2013; Epton 2014; Mehring 2014; Shuter 2014; Zullig 2014; Cameron 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015; Wittekind 2015; Harrington 2016; Smit 2016; Yang 2016).

Non‐interactive, non‐tailored

Three studies compared a non‐interactive, non‐tailored Internet programme with a non‐active control. Clark 2004 tested a very low intensity intervention for smokers having computerised tomography lung screening; a handout with a list of 10 Internet sites related to stopping smoking with a brief description of each site was compared to printed self‐help materials. Due to the low‐intensity nature of this intervention (similar to control arms in other studies), we did not include Clark 2004 in the analysis, but report results narratively. Humfleet 2013 compared an Internet‐based treatment programme to a printed self‐help guide. All participants smoking more than five cigarettes a day at study entry were offered NRT. In Wittekind 2015 participants were presented with non‐interactive/tailored smoking‐related pictures, and neutral pictures using an online platform, and the control group was sent an email explaining that participants would receive the programme after final follow‐up.

Tailored or interactive, or both

Woodruff 2007 was conducted in adolescents and evaluated an Internet‐based virtual reality world combined with motivational interviewing, conducted in real time by a smoking cessation counsellor. There was a measurement‐only control condition involving four online surveys. In An 2008 intervention group participants received USD 10 a week to visit an online college magazine that provided personalised smoking cessation messages and peer email support. The control group received only a confirmation email containing links to online health and academic resources. Both groups were informed about a campus‐wide 'Quit & Win' contest sponsored by the University Health Service. Haug 2011 evaluated a tailored and interactive Internet‐based programme for exclusive use by registered patients of participating rehabilitation hospitals. The intervention group received a complex intervention consisting of three modules (see Characteristics of included studies) and the control group received usual care. McDonnell 2011 compared a web‐based cognitive behavioural self‐help programme based on stages of change with a booklet containing the same content; material was not tailored to participants' responses. Elfeddali 2012 evaluated a programme with tailored feedback and assignments (i.e. one arm received six assignments whereas a second arm received 11) and compared this to usual care. Borland 2013 recruited smokers and recent quitters. The intervention 'QuitCoach' auto‐generated tailored cessation advice based on questionnaire responses. Participants in the control group were given contact details for web‐ and telephone‐based support. Emmons 2013 recruited childhood cancer survivors who were current adult smokers. The intervention was tailored based on participants' motivation and readiness to quit smoking, and was compared to a letter encouraging the person to quit smoking with worksheets. Free pharmacotherapy (nicotine patch or bupropion) was offered to participants and any smoking partner/spouse who wished to quit. Harrington 2016 compared 'Decide2Quit' to usual care. 'Decide2Quit' included multiple web pages on smoking and cessation‐related topics, links to other websites and interactive tools, a chat forum with a quit advisor, and tailored emails based on readiness to quit. In usual care, hospital staff would advise patients to quit and offer information about where to find support. Smit 2016 compared 'Multiple Computer Tailoring', which sent tailored feedback messages, to standard care for smoking cessation. Skov‐Ettrup 2016 'e‐quit' was a tailored and interactive Internet intervention, with optional text message support, where the website included a daily video of a person at the same stage of the smoking cessation process, exercises for increasing motivation and identifying coping strategies, tailored feedback based on level of dependence (pharmacotherapy was encouraged for those with high dependence), a blog option, and an action planning tool. The intervention was compared to usual care (sign‐posted to Danish national quitline, and callers who were ready to quit were encouraged to set a quit date and received information about pharmacotherapy if relevant). In Yang 2016 participants were randomised to an 'eChat' smoking cessation support group, which was both tailored and interactive. Information on smoking cessation was provided twice‐weekly for the first four weeks, and for the entire intervention period they could use 'WeChat' to communicate with a doctor who would answer their questions. 'WeChat' was compared to usual care. Both arms received NRT.

Lifestyle interventions

Five studies compared tailored/interactive Internet‐based lifestyle interventions to a non‐active control; we did not include these studies in the meta‐analysis as data only for smokers were not available (Oenema 2008; Epton 2014; Zullig 2014; Cameron 2015; Voncken‐Brewster 2015). Oenema 2008 tested a web‐based intervention that targeted fat intake, physical activity, and smoking. Participants who indicated that they were smokers at baseline were encouraged to complete the smoking module which was interactive and included tailored feedback. In Epton 2014 participants in the lifestyle intervention arm were directed to the 'U@Uni' website which included theory‐based messages relevant the targeted health behaviours and a planner that contained instructions to form implementation intentions. Participants were able to access information that was of interest to them, and could also download a smartphone app that was available throughout the year. The intervention was compared to a measurement‐only control. Zullig 2014 recruited participants with or at risk of cardiovascular disease. The intervention was tailored to participants' risk scores and aimed to improve multiple lifestyle behaviours (e.g. diet, exercise, smoking), and was compared to usual care. Voncken‐Brewster 2015 recruited people with or at risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In the 'Master your breath' lifestyle intervention participants received computer‐tailored feedback to promote changes in smoking cessation and physical activity, with usual care as the comparator. Cameron 2015 reported a repeat trial of Epton 2014.

Studies with follow‐up of less than six months

A further three studies were not included in the meta‐analysis because of insufficient follow‐up. Swartz 2006 compared a video‐based Internet site that presented strategies for smoking cessation and motivational materials tailored to the user’s race/ethnicity, gender and age. After follow‐up the control group had access to the programme. In Mehring 2014 the intervention website offered behavioural support and included interactive features, video clips, and quizzes; participants received feedback about their motivation and were sent corresponding short message service (SMS) messages. The control group received treatment as usual. In Shuter 2014 the intervention group received online modules designed to educate, motivate, and increase self‐efficacy to quit, and this was compared to usual smoking cessation treatment; both arms were offered a three‐month supply of nicotine patches.

Internet intervention compared to active control

Adults

Seven studies compared an Internet intervention to an active control (i.e. more intensive than usual care or self‐help only) (Swan 2010; Humfleet 2013; Borland 2013; Calhoun 2016; Skov‐Ettrup 2016). Swan 2010 was a three‐arm trial comparing an established proactive telephone counselling intervention, an interactive website based on the same programme, and a combination of phone and Internet components, all provided in conjunction with varenicline use. As well as comparing an Internet‐based intervention with a printed self‐help guide, Humfleet 2013 also included a third arm which was offered six sessions of in‐person counselling. Borland 2013 compared 'QuitCoach' which was a personalized, automated tailored cessation program based on cognitive–behavioural principles, to the 'onQ program' which was based on the same cognitive–behavioural model as QuitCoach but was delivered via a stream of SMS messages. In Calhoun 2016 Military Veterans were randomised to receive QuitNet®, a website offering personalised cessation support, access to online smoking cessation counsellors and other interactive features (i.e. forums, chat rooms, or to group or telephone counselling). In both groups interested participants received NRT. Skov‐Ettrup 2016 'e‐quit' was a tailored and interactive Internet intervention, with optional text message support, where the website included a daily video of a person at the same stage of the smoking cessation process, exercises for increasing motivation and identifying coping strategies, tailored feedback based on level of dependence (i.e. pharmacotherapy was encouraged for those with high dependence), blogging option, and an action planning tool. The intervention was compared to five sessions of telephone counselling.

Adolescents and young adults

Patten 2006 compared a home‐based, Internet‐delivered treatment for adolescent smoking cessation with a clinic‐based brief office intervention (BOI) consisting of four individual counselling sessions. Adolescents assigned to the Internet condition had access to the website for 24 weeks and abstinence was assessed at the end of this period. In Simmons 2011 university students were randomised to one of two intervention arms: (1) 'Websmoke' was a tailored and interactive Internet intervention, in which participants in the intervention were asked to create a video message about smoking to be included on the website, and participants had access to the 'Websmoke' website which included interactive components (e.g. quizzes, and a smoking cost calculator), or (2) non‐tailored and non‐interactive Internet intervention, in which participants viewed an identical web page to the 'Websmoke' condition, but the interactive features were absent and they were not instructed to create a video message. The control arm was a paper‐based version of the website, and participants were instructed to make a group video about smoking.

Lifestyle interventions

One study that compared tailored/interactive Internet‐based lifestyle interventions to an active control was not included in the meta‐analysis as data only for smokers were not available. In Frederix 2015 patients with coronary artery disease or chronic heart failure or both received an online lifestyle intervention delivered as an adjunct to non‐Internet‐based conventional centre‐based cardiac rehabilitation. The programme focused on physical activity, diet, and smoking cessation, and was compared to a centre‐based rehabilitation programme including rehabilitation sessions and exercise training sessions, 1 or more consultations with a dietician, and 1 or more consultations with a psychologist.

Studies with follow‐up of less than six months

Dezee 2013 compared GetQuit, a web‐based counselling programme with online activities, to in‐person group counselling; both arms received a standard dose of varenicline for 12 weeks.

Internet intervention plus behavioural support

Nine studies evaluated Internet programmes alongside behavioural support (Japuntich 2006; Brendryen 2008a; Brendryen 2008b; Swan 2010; Burford 2013; Borland 2013; Bannink 2014; Choi 2014; Smit 2016). Japuntich 2006 evaluated a web‐based system incorporating information, support and problem‐solving assistance which was delivered as an adjunct to bupropion and brief face‐to‐face counselling, compared to bupropion and brief face‐to‐face counselling alone. Two studies reported by Brendryen (Brendryen 2008a; Brendryen 2008b) evaluated 'Happy Endings', a one‐year programme delivered by the Internet and cell phone, consisting of more than 400 contacts by email, web pages, interactive voice response (IVR), and SMS technology, and tailored to participant responses. Brendryen 2008a recruited people attempting to quit without NRT, whilst Brendryen 2008b offered a free supply of NRT to all participants. Swan 2010 evaluated the addition of an interactive website to proactive phone counselling. In Borland 2013 integrated 'QuitCoach', which was an interactive/tailored online programme with 'QuitonQ' which involved a stream of interactive SMS messages. 'QuitonQ' included advice on quitting and motivational messages in which the user can report changes in behaviour (e.g. a quit attempt) to receive stage‐specific SMS messages. 'QuitCoach' and 'QuitonQ' were offered as a package in which users could subsequently use either or both parts. The integrated programme was compared to (1) a non‐active control arm in which participants were given brief information on web‐ and telephone‐based assistance available in Australia, and (2) SMS messaging alone. In Burford 2013 an Internet‐based three‐dimensional age progression software package was used to create aged images of the participants' faces based on a standard digital photograph, with the resulting aged image adjusted to compare how the participant aged as a smoker versus a non‐smoker. Participants also received standard two‐minute smoking cessation advice from the pharmacist. The control arm received two‐minute smoking cessation advice from the pharmacist. Choi 2014 participants were randomised to the 'Tobacco Tactics' website, which was delivered as an adjunct to telephone‐based behavioural support. The website offered tailored images and cessation feedback, with other interactive features (assessment of dependence, smoking calculator, and progress monitor, etc.). The control arm were encouraged to call 1‐800‐quit‐now. In both arms, NRT, varenicline or bupropion were available upon request. In Smit 2016 'Multiple Computer Tailoring'‐plus‐counselling participants received a tailored feedback letter, and at six weeks were offered counselling meetings with a nurse. Participants in the control arm received treatment as usual for smoking cessation.

Lifestyle interventions

In Bannink 2014 adolescents received one of two tailored and interactive lifestyle interventions as adjuncts to a behavioural component: (1) in the 'E‐health4Uth‐only' condition participants received tailored messages to reinforce healthy behavioural changes, were provided links to relevant websites and could self‐refer for face‐to‐face or email consultation with the mental health nurse; or (2) in the 'E‐health4Uth + consultation' condition participants received the same intervention as the E‐health4Uth‐only group, with those at risk of mental health problems invited for a consultation with the nurse. Interventions were compared against self‐referral to the nurse for face‐to‐face or email mental health consultation. In Frederix 2015 participants received a 'Center‐Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program', which was a tailored and interactive Internet intervention that was delivered as an adjunct to a non‐Internet‐based behavioural intervention. The 24‐week programme focused on multiple cardiac rehabilitation components and used both physical activity telemonitoring and dietary/smoking cessation/physical activity telecoaching strategies. Participants were prescribed patient‐specific exercise training protocols, and a telecoaching system to provided them with feedback by email and SMS once weekly, encouraging them to gradually achieve predefined exercise training goals. In addition, participants received emails or SMS text messages or both (once weekly) with tailored dietary and smoking cessation recommendations. The smoking cessation telecoaching programme included information on major risks associated with smoking, the health benefits of smoking cessation, and nicotine replacement therapy. The control group was a centre‐based rehabilitation programme which was a non‐Internet‐based active control arm, and included 45 multidisciplinary rehabilitation sessions and at least two exercise training sessions a week delivered over 24 weeks. The group had at least one consultation with the dietician about healthy eating, and at least one consultation with a psychologist who aimed to improve their self‐efficacy to change prior unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, and assessed the participant's mood.

Comparisons between different Internet interventions

Thirty‐one trials compared two or more different Internet interventions.

Studies comparing tailored/interactive smoking cessation interventions to non‐tailored, non‐interactive smoking cessation interventions

Follow‐up of six months or longer

Ten studies included in the meta‐analysis compared tailored/interactive interventions to non‐tailored/interactive interventions (Rabius 2008; Te Poel 2009; Simmons 2011; Wangberg 2011; Graham 2011; Mason 2012; Brown 2014; Stanczyk 2014; Mavrot 2016; McClure 2016). Rabius 2008 compared five tailored and interactive Internet services with the targeted, minimally‐interactive American Cancer Society website providing stage‐based quitting advice and peer modelling. Graham 2011 compared an interactive tailored intervention with static information‐only content on 'QuitNet'. Te Poel 2009 compared tailored to non‐tailored messages sent after participants had completed an online survey, and information was gathered through a website. Wangberg 2011 compared a multicomponent, non‐tailored intervention for smoking cessation (control) with a version of the same intervention with tailored content delivered by website and email. Simmons 2011 compared the 'Websmoke' website in which participants had access to information about the harms of smoking and benefits of quitting, and interactive components (e.g. quizzes), and videos from peers, and were asked to upload a video about their own smoking. Participants in the control group viewed an identical smoke‐free website without interactive features and were asked to provide feedback on the website. Mason 2012 compared tailored to non‐tailored messages sent after participants had completed an online survey, and information was gathered through a website. Brown 2014 compared the website 'StopAdvisor', which included advice on quitting, and interactive features (e.g. calendar, personal progress reports, the 'StopAdvisor' Facebook page, etc.), to a one‐page static website. Participants in both arms were encouraged to use medication, and to use the NHS Stop Smoking Services. In Stanczyk 2014 the interventions were both tailored and interactive Internet interventions. Text‐ and video‐based web interventions were delivered over four months, and the content of the intervention was exactly the same across the text‐ and video‐based interventions, and was tailored to motivation to quit. Participants received tailored feedback on their smoking behaviour and how to prepare to quit. The control group received web‐based generic short text advice. Mavrot 2016 compared the 'Stop‐Tabac' website which involved a series of automatic, personalised feedback reports and emails based on the participant's answers to a tailoring questionnaire, and a personal web page with progress graphs for tobacco dependence, withdrawal symptoms, etc. to a non‐tailored, non‐interactive Internet intervention based on health behaviour theories. McClure 2016 compared the 'MyMAP' intervention, which included on‐demand adaptively‐tailored advice for managing withdrawal, a secure messaging system, and personalised reports, to the 'mHealth Self‐help Quit Guide', which included psychoeducational content for quitting smoking (the content was standardised and not tailored). Both arms received a 12‐week course of varenicline. Three studies compared tailored messages to non‐tailored messages.

Studies with follow‐up of less than six months

Six studies that compared tailored/interactive and non‐tailored/interactive interventions were not included in the meta‐analysis, due to insufficient follow‐up (Strecher 2005; Stoddard 2008; Bricker 2013; Herbec 2014; Mananes 2014; Pechmann 2016). Strecher 2005 assigned purchasers of a particular brand of nicotine patch to receive either web‐based, tailored behavioural smoking cessation materials or web‐based non‐tailored materials. Stoddard 2008 evaluated the impact of adding a bulletin board facility to the smokefree.gov cessation site. Bricker 2013 compared 'Webquit.org' which was based on acceptance and commitment therapy to smokefree.gov which was a non‐tailored and non‐interactive Internet intervention . Herbec 2014 compared the 'MumsQuit' website, which contained an interactive, personalised, and structured quit plan, to a one‐page static, non‐personalised website that provided brief standard advice for users. Mananes 2014 compared a tailored/interactive version of a web‐based smoking cessation programme based on the Clinical Guidelines for the Treatment of Smoking and cognitive behavioural therapy methods to a non‐tailored/interactive version of the web page. Pechmann 2016 compared 'Tweet2Quit', a Twitter‐based intervention which involved daily discussions, automated messages and daily engagement auto‐feedback to smokefree.gov. Both arms were provided with a 56‐day supply of nicotine patches appropriate to their baseline smoking level.

Lifestyle interventions

Two studies compared tailored/interactive and non‐tailored/interactive lifestyle interventions. Dickinson 2013 compared an enhanced site of materials designed to assist participants in behaviour change, which also included an online forum where they could post issues and discuss them with other participants working on similar behavioural changes, and an 'Ask the Expert' section, where participants could post questions for the clinical team. The enhanced site was compared to a basic version of the website that had no tailored/interactive features. In Epton 2014 participants assigned to the intervention arm were directed to the U@Uni website to view the online resources, which included theory‐based messages (i.e. text, videos and links to further information) relevant to fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking status, and a planner that contained instructions to form implementation intentions; the intervention was compared to a measurement only control condition. In Schulz 2014 all groups received a health risk appraisal of physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, and alcohol and cigarette consumption. Questionnaires were used to measure the psychosocial concepts of the 'I‐Change' model. Participants were invited to change unhealthy behaviours and received feedback on all behaviours. Participants in the control arm received a "minimal intervention".

Other types of comparisons between Internet interventions

The remaining studies compared different components of Internet interventions. Etter 2005 compared the efficacy of two versions of an Internet‐based, computer‐tailored cessation programme; the control group received a shorter version modified for use by those smoking and buying NRT over the counter, although use of NRT was not a condition of enrolment.

A series of three studies by Muñoz and colleagues evaluated adjuncts to an online resource, the 'Guia', a National Cancer Institute evidence‐based intervention first developed for Spanish‐speaking smokers. In separate English language (Muñoz 2006 Study 3) and Spanish (Muñoz 2006 Study 4) studies, the control condition was the provision of access to the 'Guia' intervention and 'Individually Timed Educational Messages'. The intervention tested was the addition of an online mood management course consisting of eight weekly lessons. Muñoz 2009 also used the 'Guia' intervention as the control condition, but in a four‐arm design that evaluated the successive addition of 'Individually Timed Educational Messages', the mood management condition used in the Muñoz 2006 studies, and a 'virtual group' asynchronous bulletin board. The study recruited English‐ and Spanish‐speaking Internet users from 68 countries. Follow‐up was at 2½ months.

McKay 2008 compared the 'Quit Smoking Network', a web‐based tailored cessation programme with a multimedia component, with 'Active Lives', a web‐based programme providing tailored physical activity recommendations and goal setting in order to encourage smoking cessation.

Strecher 2008 identified active psychosocial and communication components of a web‐based smoking cessation intervention and examined the impact of increasing the tailoring depth on smoking cessation among nicotine patch users. Five components of the intervention were randomised using a fractional factorial design: high‐ versus low‐depth tailored success story, outcome expectation, and efficacy expectation messages; high‐ versus low‐personalized source; and multiple versus single exposure to the intervention components. Abstinence was assessed after six months.

In An 2013 the 'Tailored Health Message' intervention participants were required to visit the site and report on their cigarette smoking, alcohol use, exercise, and breakfast consumption. The intervention focused on building social support for healthy lifestyles, eating healthy breakfasts, increasing exercise, smoking cessation or reduction, and responsible drinking or abstinence from drinking. The 'Tailored Health Message + Peer Coach' intervention included all components of the 'Tailored Health Message' intervention but was both interactive and tailored as participants were allocated a peer coach who viewed the participants’ behavioural tracking progress charts and sent a personal video message. Both arms were compared to the 'General Lfestyle' group, which received six sessions of non‐health‐related lifestyle content over the Internet and was tailored but not interactive.

In Berg 2014 the Intervention and control arms were both tailored and interactive, but with or without emails for incentives or 'daily deals' for local businesses. Participants in both arms had access to modules that were delivered twice a week by email. Modules included short videos about smoking, advice to quit and cessation resources (e.g. pharmacotherapy options). Participants completed a timeline reporting cigarette and alcohol consumption, and time spent exercising; a graph was produced of these health behaviours over the course of the intervention. This study was not included in the meta‐analysis.

Fraser 2014 had five intervention components that were either "turned on or off" for each participant: smokefree.gov (versus a "light" website), telephone quit‐line counselling (versus none), a smoking cessation brochure (versus a "light" brochure), motivational e‐mail messages (versus none), and mini‐lozenge NRT (versus none).

McClure 2014 tested 16 variations of the 'Q2' intervention based on different stages of readiness to quit. Each participants' intervention was similar, but varied based on the randomly‐assigned experimental factor levels: 'message tone', 'navigation autonomy', 'proactive emails', and 'testimonials'.

Bolman 2015 participants received an interactive and tailored Internet‐based intervention with or without an email letter. In both arms participants received a series of tailored email letters aiming to encourage cessation. The experimental group also received tailored advice on action planning based on the participant’s response to questions about action planning at baseline.

In Borland 2015 all three arms were tailored and interactive: (1) 'QuitCoach' was a web‐based automated tailored advice programme that provided a tailored advice letter based on the participant's answers, and allowed smokers to quit to their own schedule; (2) 'QuitCoach + Rapid Implementation' included participants who had not committed to a quit date within the next two days; (3) 'QuitCoach + Structured Planning' included provision of encouragement and tools for structured planning.

Houston 2015 compared three tailored and interactive Internet interventions, with or without additional motivational messaging: (1) Decide2Quit.org was a smoking‐cessation website that included motivational information tailored to readiness to quit and other baseline factors, cessation barrier calculators and games, resources about smoking, seeking social support, and talking to a doctor about quitting; (2) The 'Messaging Group' intervention arm were allocated to Decide2Quit.org, and also received brief motivational email messages that were tailored to an individual smoker’s readiness to quit, and included messages written by smokers for other smokers; (3) The 'Personalised Group' intervention arm were allocated to Decide2Quit.org, received the same tailored motivational emails as in the 'Messaging Group', and in addition they had access to personal online support from trained tobacco treatment specialists, and a link to an online support group (BecomeAnEx.org).

Cobb 2016 compared a Facebook intervention with or without reminders for participants to use the website. The Facebook intervention was based on the '5As' model (i.e. Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange). Participants were asked if they smoked and were advised to quit, participant's readiness to quit was assessed and they were encouraged to plan a quit date; other interactive features were included (i.e. quit‐day countdown, savings to date). In the 'Facebook intervention with alerting' arm participants received additional online alerts to remind them to log in. This study was not included in the meta‐analysis, as variations of diffusion were compared rather than interventions.

Moskowitz 2016 compared high and low reinforcement, plus the 'QiW' programme. The intervention was a tailored/interactive cognitive‐behavioural programme based on the stages of change, and included short introductory videos using computer animations that were available in English and Korean. The high‐reinforcement condition included online interim surveys with financial incentives for these assessments and also for programme completion, and participants received reminders about the incentive with a monthly reminder to complete the interim survey.

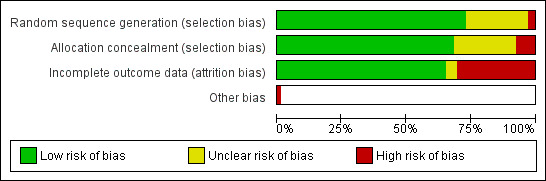

Risk of bias in included studies

We have rated risks of bias in the following domains: (1) selection bias: random sequence generation and allocation concealment; (2) attrition bias; and (3) other potential sources of bias. While we rated most studies at low risk of bias in most or all domains, we judged a number of studies to be at high or unclear risk of bias. Over a quarter were at high or unclear risk of attrition bias, characterised by overall attrition rates greater than 50%, or more than 20% difference in attrition rates between trial arms. Several studies were at unclear risk, as there was insufficient detail to properly assess risks of bias for random sequence generation or allocation concealment or both. Figure 2 is a graphical representation of risks of bias across domains; see Characteristics of included studies for details of risk of bias assessments for each study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We judged two studies to be at high risk of bias for both random sequence generation and allocation concealment. In Burford 2013, participants were recruited and assigned by the researcher to the different arms of the study on alternate weeks. Skov‐Ettrup 2016 allocated participants by repeatedly applying a fixed sequence of four numbers. Fourteen studies did not provide sufficient detail with which to assess methods of random sequence generation and hence we rated them as 'unclear' (Clark 2004; Strecher 2005; Japuntich 2006; Patten 2006; Woodruff 2007; Haug 2011; Dickinson 2013; Emmons 2013; Choi 2014; Fraser 2014; McClure 2014; Wittekind 2015; McClure 2016; Yang 2016).