Abstract

Precarious work (i.e., work that is insecure and uncertain, often low-paying, and in which the risks of work are shifted from employers and the government to workers) has emerged as a serious concern for individuals and families and underlies many of the insecurities that have fueled recent populist political movements. The impacts of precarious work differ among countries depending on their labor market and welfare system institutions, laws and policies, and cultural factors. This article examines how people in six advanced industrial countries representing different welfare and employment regimes—Denmark, Germany, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States—differ both in their experience of precarious work and in outcomes of precarious work such as job and economic insecurity, entry into the labor force, and subjective well-being. It also suggests a new social and political contract needed to address precarious work and its consequences.

I. INTRODUCTION

The growth of precarious work since the 1970s has emerged as a serious challenge and major concern in the contemporary world. By “precarious work” I mean work that is uncertain, unstable and insecure and in which employees bear the risks of work (as opposed to businesses or the government) and receive limited social benefits and statutory entitlements (Vosko 2010; Kalleberg 2011; Kalleberg and Hewison 2013; Breman and van der Linden 2014). It has widespread consequences not only for the quantity and quality of jobs, but also for many non-work individual (e.g., mental stress, poor physical health, uncertainty about educational choices), family (e.g., delayed entry into marriage and having children) and broader social (e.g., community disintegration and disinvestment) outcomes. Moreover, precarious workers’ insecurities and fears have spilled over to forms of protest that call for political responses to address these concerns.

While work has always been to some extent precarious, especially for more vulnerable groups in the population such as women and minority men, there has been a recent rise in precarious work especially for majority men in rich democratic, post-industrial societies. The growth of precarious work has also accelerated the exclusion of certain groups from economic, social and political institutions, such as when people are unemployed for long periods of time, left outside systems of social protections, and disenfranchised from voting and participation in the political process.

The upsurge in precarious work in some rich democracies (such as the United States) began in the mid-late 1970s and 1980s, while it occurred a bit later in others. In all cases, the consequences of precarious work were exacerbated by the global economic crisis of 2008–2009. Pressures on governments to implement policies of fiscal austerity and welfare state reorganization accompanied—and are partly responsible for—the rise in precarious work, as countries have struggled to respond to weakening financial situations and an increasingly fragile global economy. These developments have created challenges for state policies and for businesses and labor as they strive to adapt to the changing political, economic and social environment. It also raises important questions for social scientists seeking to understand the sources of these changes in employment relations and their likely consequences for workers, their families, and societies.

The recent rise of precarious work is associated with major economic shifts in the global economy and, as is common in major transitions, has created a great deal of uncertainty and insecurity. Governments and businesses have sought to make labor markets more flexible to compete in an increasingly competitive world economy. This has also led to the retrenchment of welfare and social protection systems in many countries and reconfiguring relationships between national and local levels of government and between public and private providers of social welfare protections. This has shifted the risks and responsibility for many social insurance programs to individuals and families.

Individuals differ in their vulnerability to precarious work, however, depending on their labor market power. On the one hand, it means insecurity and instability for many people, especially those who are more vulnerable because they lack labor market power (such as undocumented workers, who are probably the most precarious workers of all in these rich democracies). On the other hand, the flexible employment relations associated with precarious work may provide those who possess skills that are in high demand (such as highly skilled computer programmers or knowledgeable consultants) the opportunity to benefit from being able to move more freely from one employer to the next. For them, insecure and unstable work may provide greater flexibility, rewarding some types of creativity, promoting individualism, and enabling some forms of social and geographic mobility (Horning 2012).

While the growth of precarious work is common to countries, its incidence and consequences differ depending on the countries’ social welfare protections and labor market institutions. Relations between the state and markets are central to explanations of differences among employment relations, and hence to variations in the experience of precarious work. Social welfare protections and labor market institutions, in turn, result from a country’s political dynamics and the power resources and relations among the state, capital, labor and other civil society actors and advocacy groups (such as non-governmental organizations) that shape the degree to which workers can protect themselves and their families from the risks associated with work and flexible labor markets. Moreover, cultural variations in social norms and values—such as those underlying the gender division of labor, whether families are characterized by dual earners or a male breadwinner-female homemaker model, and the importance placed on equality and the desirability of collective as opposed to individual solutions to social and economic problems—help to generate and legitimate a country’s institutions and practices. Work and employment relations are also shaped by the demography of a country’s labor force, such as its age distribution and patterns of immigration.

I develop and demonstrate my arguments about the impacts of social welfare protections and labor market institutions on precarious work and its consequences by comparing six rich democracies: Denmark, Germany, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. These six countries represent diverse models of capitalism: Social Democratic nations (Denmark); coordinated market economies (Germany, Japan); Southern Mediterranean economies (Spain) and liberal market economies (the United Kingdom and United States). These countries differ in their employment and social welfare regimes and exemplify the range of ways in which institutional, political, and cultural factors affect precarious work and its outcomes. They also typify dissimilar responses of governments, employers and workers to the macro-structural economic, political and social factors driving the growth in precarious work and creating pressures for greater austerity and reorganizations among welfare and labor market institutions.

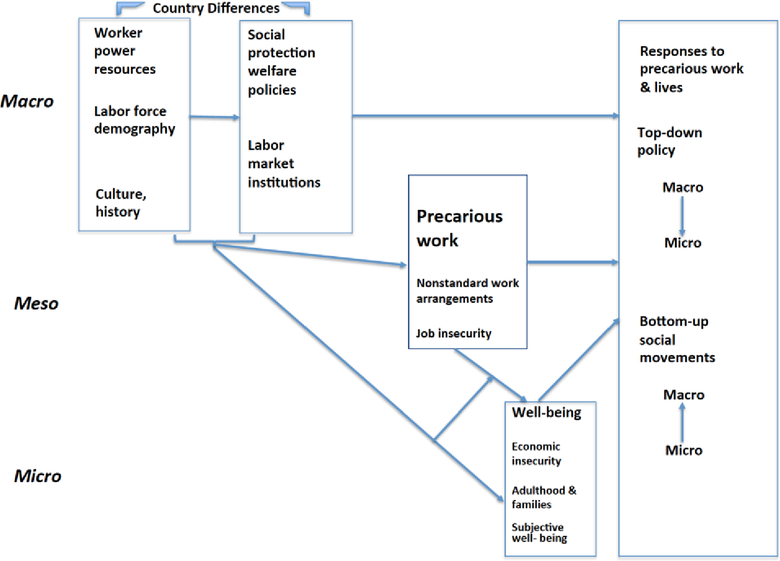

Figure 1 describes my conceptual framework for studying the causes, manifestations and consequences of precarious work. The model identifies the interrelations among phenomena operating at multiple levels of analysis: at the macro, meso and micro levels. Country differences represent macro-level social, political, economic and cultural forces. Precarious work refers to the meso-level employment relations between employers and their workers. Macro- and meso-level structures are the fundamental institutions of capitalist systems that have important implications for micro-level outcomes such as workers’ well-being. Finally, precarious work and negative aspects of well-being (as indicated by high economic insecurity, difficulties in making the transition to adulthood and forming families and low subjective well-being) may lead to social and political movements to protest these conditions. The latter are examples of how micro forces can lead to macro-level changes. In addition, macro-level government policies might affect meso- and micro-level changes.

Figure 1.1.

Conceptual Model

In this article, which is based on my 2018 Geary Lecture and recent book (Kalleberg 2018), I first discuss the rise of precarious work and then how differences among these six countries influence the incidence and consequences of precarious work. I next summarize some of the economic and non-economic consequences of precarious work, political reactions to precarious work and needed policies, and several plausible future scenarios related to work and well-being.

II. COUNTRY DIFFERENCES

Different social, economic, and political structures typical of capitalist societies produce divergences among them in their employment systems and institutions. Two influential neo-institutional theories of diversity among capitalist countries identify the employment, labor market and social welfare protection systems that shape the nature and consequences of precarious work for individuals and their families: the “Varieties of Capitalism” (VoC) or “production regime” theory approach (Hall and Soskice 2001); and the Power Resources Theory (PRT) (e.g., Stephens 1979; Korpi 1983, 1985; Esping-Andersen 1990).

The VoC theory is especially relevant in accounting for differences in labor market institutions such as active labor market policies and collective bargaining. These institutions are linked to the employment systems within a country—especially educational and skill formation systems—and associated patterns of labor market mobility. On the other hand, the PRT emphasizes how the differential power resources of workers exercised through political parties and unions helps to produce variations in the inclusiveness of welfare provisions and the degree of unemployment insurance protection and social spending generally.

These theories help explain differences among these countries in two key social welfare protection policies: (1) the generosity of welfare spending, or those monies (both public and required from private sources) that are designed to provide protections against illness, old age, disability, poverty and other kinds of difficulties faced by persons over the course of their lives; and (2) and the degree to which unemployed persons receive financial support (usually in the form of unemployment insurance payments). These financial supports provide a cushion or economic safety net to support people during times of unemployment. These welfare system policies are especially important for the degree of economic insecurity.

In addition, there are country differences in several key labor market institutions: (1) the nature and extent of a country’s active labor market policies, which are designed to help workers transition between jobs and from unemployment to paid work; and (2) the degree of employment protections for “permanent, regular” workers and the rules governing the use of temporary and other nonstandard workers. These labor market institutions are especially important for levels of job insecurity.

The generosity of public spending on welfare benefits and active labor market policies is relatively high in Denmark, Germany and Spain, and relatively low in Japan, the U.K. and U.S. Employment protections for regular workers is higher in Germany, Denmark and Spain compared to Japan, the U.K. and U.S. (see Kalleberg 2018: Chapter 2).

2.1. Varieties of Liberalization of Social Welfare Protection and Labor Market Systems

All of these countries have encountered pressures to liberalize their economies and labor markets and all have adopted some form of neoliberal policies, but they have done so in divergent ways, depending on the constellation and dynamics of political, economic and social forces that characterize the country (see Thelen 2014).

Embedded flexibilization (Denmark) involves the adoption of greater labor market and social welfare flexibility within an inclusive framework defined by a broad set of collective bargaining structures and strong union presence. Along with state policies to minimize wage inequalities, this has resulted in a relative collectivization of risks.

Dualization (Germany, Japan, Spain) entails the protection of “core” workers from market risks at the expense of relatively unprotected “peripheral” workers. A protected group of insiders or core workers enjoy long-term contractual relations and comparatively high levels of security while those in the periphery, or outsiders are generally employed in non-regular jobs with relatively few protections. Japan’s economy has traditionally been dualistic, while dualism in Germany is more recent as it emerged within the past thirty years or so and was precipitated by de-industrialization and the failure of unions to organize workers in the private service sector. Spain has long been characterized by strong employment protections for regular workers and a strong insider-outsider divide.

Finally, deregulatory liberalization (in the United Kingdom and United States) involves the replacement of collective mechanisms of labor regulations by the imposition of market processes, shifting the risks of work to individuals.

III. PRECARIOUS WORK

There are two main approaches to conceptualizing (and hence measuring) the three main components of precarious work (i.e., insecurity and uncertainty associated with jobs; low economic and social benefits; and lack of legal protections).

One approach focuses on the form of the employment relationship, differentiating between the standard employment relationship (SER) and various forms of nonstandard work arrangements. The most commonly used indicator of nonstandard work is temporary work, which includes those who are hired for fixed or limited terms or tasks as well as those who are hired through temporary employment agencies, labor brokers or dispatch agencies. Others types of nonstandard work include: contract work (comprising employees of contract companies as well as independent contractors and “no account” self-employed persons who do not have any employees); irregular and casual employment; informal economy work; short-term work; and involuntary part-time work.

In general, nonstandard forms of work are precarious because they are uncertain and insecure and, more importantly, lack the social and statutory protections that have come to be associated with regular, standard employment relations in the early post-World War II period. Categorizing nonstandard work arrangements as precarious assumes that classifications such as temporary jobs capture the features associated with the three dimensions of precarious work sufficiently to serve as a good proxy for them.

We can get a overall picture of the rise of nonstandard work arrangements by contrasting regular, full-time employment with a global indicator that combines workers on temporary contracts, part-time jobs, and own account self-employed persons. A recent study of 26 European OECD countries using such a global indicator showed that over half of all jobs created in these countries between 1995 and 2013 were in these nonstandard work arrangements: about half of the jobs created between 1995 and 2013, and about 60 percent of those created between 2007 and 2013 were in nonstandard jobs (OECD 2015). Further, in 2013, about one-third of all jobs in these countries were in nonstandard work arrangements, divided about equally among temporary jobs, permanent part-time jobs, and self-employment.

The expansion of nonstandard work differs among the six countries. In Spain, 22.7% of the jobs created between 1995 and 2007 were in nonstandard jobs, compared to 12.7% in Germany. The percentage of nonstandard jobs declined by 0.5% in Great Britain and 7.45% in Denmark. By contrast, the percentage of jobs created between 2007 and 2013 that were nonstandard increased slightly in Great Britain (3.2%) and Germany (2%), but declined in Spain (8.9%) and Denmark (0.5%). In the United States, the percent of employed persons who worked in alternative work arrangements (defined as independent contractors, on-call workers, temporary help agency workers and workers provided by contract firms) increased from 10% in 1995 to 10.7% in 2005 and rose to 17.2% in 2015. By far the largest such alternative work arrangement was independent contractors, which grew from 6.3% in 1995 to 6.9% in 2005 and 9.6% in 2015 (Katz and Krueger 2016).

Countries with relatively high employment protections—such as Spain and Germany—also have relatively high levels of temporary work. By contrast, the percentage of temporary workers is much lower in the United States and the United Kingdom than in the other four countries, as well as compared to the OCED countries overall. The low levels of temporary work in these two liberal market economies reflects the weak employment protections in these countries, as employers can more easily lay off or fire permanent workers “at will” without the need for the flexibility that comes with temporary work.

A second approach to precarious work emphasizes job insecurity, which can be assessed both objectively (e.g., the probability that a person will lose a job and/or obtain a comparable new one) and in terms of workers’ subjective perceptions of and concerns about these objective realities. While job insecurity is generally becoming the new normal situation of work in contemporary capitalism, the degree to which people perceive their jobs are insecure and the consequences of this will differ among countries depending on their social welfare protection and labor market institutions, in addition to individuals’ labor market power.

A common objective indicator of job insecurity is job instability, measured by length of employer tenure. Length of employer tenure declined in all six countries since the early 1990s for prime-age men, due to the decline of standard employment relations (see Kalleberg 2018).

Job insecurity is relatively low in Denmark, whether this is measured objectively by the risk and economic consequences of unemployment or perceived cognitive and affective job insecurity. The Danes score lowest among the six countries on the OECD labor market insecurity index (see Hijzen and Menyhert 2016; Kalleberg 2018), though this was due more to the relatively generous unemployment insurance provisions in Denmark than to the actual risk of job loss. That the risk of unemployment is not particularly low in Denmark is consistent both with the relatively low employer tenure and the prominent role played by flexicurity policies in that country. Denmark’s active labor market policies provide support to those who lose their jobs by helping them to receive additional job-related training and placement services that facilitate their re-entry into the workforce, and by generous labor market policies that offer an economic cushion that enables the unemployed to maintain a reasonable standard of living while searching for a new job. The results for Denmark also reiterate the importance of workers’ institutional and associational power, such as the higher union density and collective bargaining coverage in Denmark, which in conjunction with the policies of Social Democratic political parties led to the social welfare protection and labor market policies that reduce job insecurity.

Is Temporary Work Precarious?

By definition, temporary jobs are insecure and uncertain. Whether we consider temporary jobs to be precarious, however, is contingent on the nature of countries’ labor market and social welfare protection institutions, as well as their labor laws and statutes covering work and employment. In some cases (such as Denmark), social protections tend to be universal and based on citizenship, while in other countries workers must work a certain number of hours or have minimum contribution periods to qualify for protections such as unemployment insurance or health insurance and pension coverage.

The risks associated with temporary employment thus depend on how social protections are tied to the employment relationship. Some countries have sought to make nonstandard work arrangements less precarious, for example, by extending social protections to nonstandard work and using collective bargaining and active labor market policies to regulate and enhance the quality of nonstandard work (Adams and Deakin 2014). In addition, some people also prefer temporary jobs—especially if they are associated with social protections—so as to obtain greater flexibility in their working lives to be able to give greater attention to caregiving and other family obligations. For example, temporary jobs can give highly skilled workers (such as nurses) more flexible career prospects and greater remuneration.

Moreover, some temporary jobs provide stepping-stones to more permanent jobs while others represent dead-ends. In Spain, temporary workers receive relatively little employer-provided training compared to permanent workers and small proportions of temporary workers subsequently move to permanent jobs. By contrast, temporary workers in the liberal market economies of the U.S. and U.K. are more likely to be able to transition to permanent jobs as temporary jobs provide workers with opportunities to develop skills and try out different kinds of work, while employers use temporary jobs to screen and evaluate potential regular employees.

IV. WELL-BEING

I summarize the consequences for individuals resulting from precarious work and in terms of three major aspects of well-being: economic insecurity; the transition to adulthood and family formation; and subjective well-being or happiness. Widening the lens to examine diverse consequences of precarious work highlights its wide-ranging effects on peoples’ lives.

4.1. Economic Well-Being

Economic insecurity denotes concerns about having sufficient economic resources to provide for oneself and one’s family. The degree of economic insecurity depends on one’s (and the family’s) human and social capital resources as well as on characteristics of the welfare state. Objectively, we can compare countries in their levels of earnings and degree of earnings inequality, incidence of low-wage jobs and extent of the population living in poverty, the non-income components of the social wage, and the stability of earnings. Subjectively, countries differ in the degree to which people perceive whether their economic situations enable them to live comfortably and maintain a minimum standard of living as opposed to having economic difficulties.

Social welfare protection policies and institutions are important for shaping the consequences of precarious work for both objective and perceived economic insecurity. The data tell a consistent and coherent story: economic insecurity is lowest in Denmark and Germany; and highest in the liberal market economies of the U.K. and U.S. (Kalleberg 2018: Chapter 5).

The lower levels of economic insecurity in Denmark—reflected in the high levels of earnings and low earnings inequality, low proportions of people working in low-wage jobs and in poverty, high economic and social protections, and low perceived economic insecurity—are all in line with the greater inclusiveness of Danish labor market institutions, which extend the gains made by unions and those with more power to those with relatively less power. The relatively low economic insecurity in Denmark also follows from the generous system of social protections in that country, which is based on high levels of public spending on welfare programs and income replacement when one becomes unemployed. This is also the case to a lesser extent in Germany, which also has high earnings quality, low proportions in poverty and high social protections, but also has a substantial number of low-wage jobs.

People in the two liberal market economies—the United Kingdom and the United States—have higher levels of economic insecurity, both in terms of lower earnings quality, higher proportions of people living in poverty, and lower social wages than the Danes or Germans. Those in the U.K. are also more apt to feel economically insecure. But while earnings quality is lower in both countries than in Denmark and Germany, this is mainly due to relatively high earnings inequality in the U.S. while it results primarily from lower average earnings in the U.K. Moreover, the proportion living in poverty is considerably higher in the U.S.

More dramatic, though, are the differences in the social wage between these two liberal market economies that result from the greater availability of economic and social supports in the U.K. that help people to mitigate various types of life course risks. The advantages for economic security provided by the universal system of health insurance in the U.K. is perhaps the most familiar, though the gaps in supports for widows and for older people are also stark. These differences between the U.K. and U.S.—which are similar on many of their labor market institutions—illustrate vividly the importance of social protections for diminishing the impacts of precarious work on economic insecurity.

4.2. Transition to Adulthood and Family Formation

Precarious work has made it especially difficult in some countries for young people to make life course transitions such as gaining a firm foothold in the labor force, moving out of the home of one’s origin, and marrying and having children. Precarious work affects these life course transitions because the job and economic insecurities it engenders have made it difficult for young people to establish career narratives that lead to orderly and stable life plans. These forms of insecurity also affect the degree to which peoples’ economic resources are sufficient and stable enough to create confidence that they will be able to live on their own or to form and support families.

Labor market institutions and policies that enable young people to gain access to regular jobs as opposed to forcing them to take temporary, often dead-end jobs are critical for helping them obtain a foothold in the labor market. Vocational and training institutions that ease the move into permanent positions are key aspects of employment systems that help workers make the transition from school and home of origin to secure footholds in the labor market. Social welfare protection systems that rely on family supports rather than public welfare provisions encourage young people to remain with their parents until they can enter jobs that they are relatively happy with. Moreover, cultural norms and values affect the rigidity of the transitions between life course events as well as whether “failing to launch” is viewed as a stigma or a reasonable adaption to difficult economic times.

The ability to gain a solid foothold in the labor market is especially important for moving on to the other life course stages, such as moving out of the parents’ home and establishing a household. This is shown most dramatically in countries such as Spain and Japan, where young adults are taking longer to leave home due to not being able to find regular employment and young men (especially in Japan) are having difficulty finding suitable marriage partners because they have been unable to obtain a regular job that provides the promise of future advancement and economic security (e.g., Piotrowski, Kalleberg and Rindfuss 2015). In both Japan and Spain, there is a wide generational divide produced by a dual labor market system that favors older workers at the expense of the young. Older workers enjoy considerable employment protections (more legal in the case of Spain, more cultural in Japan) and so younger workers have difficulty in obtaining regular jobs, and thus must settle for (often a series of) non-regular positions that often do not lead to permanent positions. In Japan, for example, it is estimated that only about 2 percent of non-regular workers transition to regular employment each year (Devine 2013), since Japanese employers prefer to hire recent high school or college graduates, depending on the educational requirements of the job.

4.3. Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being represents a person’s overall affective evaluation of the quality of one’s life and is generally measured by concepts such as life satisfaction or overall happiness. The concept of subjective well-being has attracted a great deal of attention from social scientists who see this as a means of evaluating the impacts of non-economic as well as economic utilities on one’s overall quality of life.

A rational life plan that involves establishing goals for what one hopes to accomplish during life and a strategy for attaining them plays an important role in Rawls’ (1971) theory of justice. He argues that people will be happy when they are able to carry out their life plan successfully, as it indicates that the person is able to satisfy his or her rational desires. Unfortunately, the growth of precarious work has made constructing a rational life plan or career narrative increasingly difficult to achieve for many people in the rich democratic countries. Sennett (2000) vividly described the “corrosion of character” resulting from the transformations associated with precarious work, which have made it difficult to achieve coherence and continuity in one’s work experiences and reduced the ability of people to think in terms of a long-term plan. The insecurity associated with precarious work, as well as the uncertainty associated with transitions to adulthood and family formation, result in physical and psychological distress, as well as lower objective and subjective well-being (e.g., Scherer 2009).

Labor market and social protection institutions affect subjective well-being directly by contributing to the overall social, economic and political contexts that shape external conditions (such as the extent of economic inequality and the degree and duration of unemployment) as well as by ameliorating or enhancing the impacts of these external conditions on subjective well-being. In addition, country differences among countries in subjective well-being are also affected by dissimilarities in political governance mechanisms, the degree of trust that people have in their governments and other institutions, the extent of worker power such as amount and strength of unions, as well as cultural factors such as religion and the degree of optimism.

Many of these country differences—especially those related to labor market and social welfare institutions—are amenable to public policy intervention. Labor market institutions such as active labor market policies and social welfare protections are within the purview of governments and social and political actors, who can take steps to reduce the impacts of precarious work on individuals’ individuals’ psychological and economic well-being. Hence, addressing precarious work becomes a matter of concern for public policy.

V. RESPONSES TO PRECARIOUS WORK AND LIVES

Precarious workers share experiences of anger (due to frustration over blocked aspirations), anomie (a passivity resulting from despair about not finding meaningful work), anxiety (due to chronic insecurity), and alienation (due to lack of purpose and social disapproval). These mutual understandings make the precariat a potentially dangerous class, capable of being mobilized by different groups for various ends, ranging from democratically based solutions—as in the New Deal in the United States in the 1930s—to authoritarian movements that blame immigrants and the poor for the precariat’s insecurity (Standing 2011). The latter was what Polanyi 1957 [1944] was most concerned about, and his fears were realized with the adoption of totalitarian governments in Germany and Italy in the build-up to World War II (see also Harvey 2005).

The rise of precarious work after long periods of economic and social development after World War II has raised apprehensions that hard-won gains by workers during this period may be lost. The proliferation of precarious work undermines the socio-political stability that Fordism (with its associated Keynesian policies and expanded welfare state) had provided in the post-World War II period in the rich democracies. The consequences of precarious work and precarious lives have triggered responses in the form of social and political movements that have sought to mitigate the most serious costs for workers and their families and have deeply affected the politics of post-industrial countries. Two main types of responses can be categorized as those emanating from: the “bottom up” as workers seek to create macro-level structural changes through social movements; and “top-down” efforts whereby governments (perhaps prodded by protest movements) enact policies (such as more generous welfare policies) to protect workers from the consequences of precarious work.

Workers have sought to counter this rise in precarious work and its consequences through both social movements and actions by organized unions and political parties. These efforts have sought to address the new risks for workers and their families that are raised by the changes in employment relations and reconfiguration of social welfare protection systems. Moreover, political dynamics among the state, employers and workers have focused both on policies designed to help people adapt to precarious work through social insurance and skill acquisition, as well as emphasized ways of reducing precarious work (what Hacker 2011 has called “pre-distribution”) by changes in labor and employment laws.

In order to address issues related to precarious work, policies in three general areas are necessary to maintain flexibility for employers yet still provide individuals with ways to cope with the negative consequences produced by such flexibility. These include: (1) a safety net and various kinds of social protections to collectivize risk and help individuals cope with the uncertainty and insecurity associated with the growth of precarious work; (2) greater access to early childhood and formal education as well as lifelong education and retraining in order to prepare people for changes that will occur in jobs; and (3) changes in labor regulations and laws to protect those in both regular and non-regular employment.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

The transformation of employment relations represented by the recent rise of precarious work presents important challenges for individuals, families, businesses and societies. The growth of insecure, uncertain jobs that have few social and legal protections departs from the more stable, standard employment relations of the three decades after World War II. We must be careful not to glamorize this earlier era of relative stability and high economic growth, as it was much more beneficial to white men than for women and minorities. Nevertheless, we are now in a different era, a new age of precarious work that represents a fundamental shift toward widespread uncertainty and insecurity. People who have the skills and resources to navigate successfully rapidly changing labor markets have welcomed this new era as an opportunity to achieve their market potential by moving between organizations. Others, perhaps the majority, are more economically insecure, often have difficulties in forming families, and experience low subjective well-being.

Why has there been a rise in precarious work in rich democracies, with their high standards of living and privileged positions in the world economy? And, how and why do people experience precarious work differently in countries with dissimilar institutions and cultures? I sought to answer these puzzles by studying six countries—Denmark, Germany, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States—that differ in their social welfare protection and labor market institutions and hence illustrate the variation among rich democratic countries in the incidence and consequences of precarious work.

There are common trends among the six countries. All have had to respond to similar political and economic forces unleashed by an increasingly global and technology-driven economy, as well as constraints on state budgets produced by slowdowns in economic growth coupled with the aging of labor forces and more diversity in what labor forces need to be productive. In all six countries, there has been a decline in long-term employment among prime age men. And, all countries have liberalized their labor markets and restructured their social welfare protections to cope with the growth of precarious work. While precarious work is universal, it is cross-nationally variable, as the nature of this liberalization has differed, depending on a country’s political situation and the strength of workers, from a general deregulation of markets and social protection institutions (the U.K. and U.S.), to dualism (Germany, Japan, Spain), to a more collective sharing of risk (Denmark).

Differences among these countries in their social welfare protection and labor market institutions and policies affect both precarious work and its consequences for well-being. Some countries have been able to address the concerns raised by precarious work more successfully than others by re-establishing and expanding social safety nets, managing labor market transitions more effectively, and implementing social and economic reforms that are targeted at the needs and choices of increasingly diverse labor forces. The empirical evidence suggests the following five conclusions (see Kalleberg 2018).

First, the generosity of public spending on social welfare benefits and active labor market policies is relatively high in Denmark, Germany and Spain, and relatively low in Japan, the U.K. and U.S. Differences in these policies can be traced to differences in the power of workers and political dynamics in these countries.

Second, labor market institutions affect the incidence of precarious work. Temporary work is less common in the liberal market economies of the United Kingdom and United States and relatively high in Spain. These differences are associated with the low levels of employment protections in the U.K. and U.S. and the high employment protections in Spain. Moreover, the degree to which temporary jobs can be considered precarious depends on the nature of the social protection systems in a country, such as whether temporary workers are afforded the same kinds of welfare entitlements as those working in regular jobs.

Third, generous social welfare benefits are linked to less economic insecurity, which is lowest in Denmark and Germany and highest in the liberal market economies of the U.K. and U.S. The latter countries differ, however, in the social wage due to the greater availability of economic and social supports in the U.K. that help people to mitigate various types of life course risks.

Fourth, young persons have difficulty gaining a solid foothold in the labor market especially in Spain, with its high levels of employment protection that relegates young workers to temporary jobs. Trouble establishing families is especially pronounced for young males in Japan, with its rigid markers of the transition to adulthood.

Fifth, the generosity of social welfare protections, along with high levels of active labor market policies, is associated with greater subjective well-being in a country.

While institutional and cultural factors may modify the basic thrust toward the rise of precarious work, the underlying political, economic and social trends responsible for precarious work are intimately linked to the dominance of neoliberalism, which “has become a machine that moves of its own accord. It is the accepted logic of our time” (Schram 2015: 173–174). The desirability of market-oriented solutions to economic, political and social problems has become an accepted article of faith by governments and businesses alike, who regard the current situation as the “new normal” in a new era of capitalism characterized by a global, technologically-driven economy.

Across the political spectrum, leaders yearn nostalgically for years past, such as the three decades of after World War II, with its high levels of economic growth and equality. Those on the left harken back to the social protections of the New Deal and Keynesian welfare states, while those on the right pine for the periods of high growth in the early period of the neoliberal era. There is no return to the past, however, as the conditions that made that era possible have now disappeared; we must find new ways to adapt to the changing nature of work and employment relations.

The implementation of a new social contract—with its expanded and portable safety net, better managed labor market transitions, and appreciation for the needs of a diverse labor force—ultimately requires, of course, an associated political contract among the state, business and labor that seeks to balance the needs for flexibility and security. Achieving such a new social-political contract constitutes one of the great challenges of the first part of the 21st century. The kinds of policies, neoliberal or otherwise, that will come to dominate in these countries are of course uncertain. I can imagine both dystopian and more utopian futures.

6.1. Plausible Futures

It is relatively easy to envision a variety of dystopian futures, as here one must only extrapolate from current trends. The confluence of forces related to globalization, technological change, the financialization of firms’ organization of work, and weak worker power may well continue and perhaps extend trends such as: expansion of low-wage jobs; outsourcing and subcontracting of the production of goods and services to lower-wage firms; growing polarization between good and bad jobs and increasing inequality; expansion of digital platforms creating short-term and poorly protected jobs (the “Uberization” of the economy); and so on. Moreover, the implications of the automation of jobs are unclear and many fear that it will reduce drastically the need for workers.

It is more difficult to imagine utopian possibilities, given the priorities of current political and economic debates in these countries. Necessary conditions for any optimism require strengthening and expanding social welfare protections and providing active labor market policies to facilitate job mobility. But more comprehensive and long-term solutions require more basic changes.

One optimistic scenario is Beck’s notion of an emerging “post-full-employment society” or “multi-activity work society,” that defines work as something beyond market work, an idea which is similar to Standing’s (2011) vision of work as going beyond paid labor. The idea of work is broader than market work and includes many activities that produce non-economic value as well. Beck envisions a multi-activity society wherein people are able to shift their actions over the course of their lives among formal employment (albeit perhaps working fewer hours), parental labor, and civil labor (i.e., work in the arts, culture and politics, which helps the general welfare). The latter activity could be rewarded with “civic money” that is not a handout from the state or community but a return for engaging in these activities. Each person would control her own time-capital that she can allocate to different activities over time. Beck advocates that paid work and civil labor should complement each other and calls for greater equality of housework and outside care work with artistic, cultural and political civic labor in the voluntary sector, which he believes will help create a gender-neutral division of labor.

Vosko’s (2010) vision is similar to Beck’s. She recognizes the low chances that there will ever be a return to the standard employment relations that characterized the post-World War II period and thus suggests possible alternatives that include: a new gender contract that places greater value on caregiving; and a “beyond employment” approach (see also Supiot 2001) that decouples social protection from labor force status and adjusts types of work to diverse stages in the life cycle.

If we are to formally define work as something beyond paid market work, it is essential to decouple economic security from market work. One increasingly popular option, Universal Basic Income (UBI), is very controversial for economic, political and cultural reasons, and it is unclear how this would work on a large scale. A major objection to the UBI is that it redistributes value that has already been created in society. Its viability depends largely on how much economic growth there will be in the future since as economic growth slows, the contests over the distribution of a shrinking economic pie become very fraught. Some influential economists feel the period of growth is over (e.g., Gordon 2016), while other are more optimistic. We really do not know what is possible with respect to economic growth, however, since austerity policies in the rich democracies have stalled social investments in innovation, research and development in recent years. It is critical to ramp up such investments if we hope to stimulate economic growth.

We also need to re-conceptualize not only the meaning of work but also our understanding of what constitutes value in a society. The commonly used economic indicator of value, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is increasingly unable to capture developments such as widening inequality and the rise of precarious work. Alternative, “beyond GDP” indicators of well-being are needed that shift the emphasis from measuring economic production to assessing the multiple dimensions of peoples’ well-being, as argued forcefully by Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi (2009).

The recent rise of precarious work represents a dramatic change in relations among workers, employers and governments from the standard employment relations that characterized rich democracies in the three decades after World War II. Upheavals such as those created by precarious work generate anxiety and uncertainty as people, organizations and governments scramble to adapt to a new reality. The challenge is to respond to these changes by policies and practices that promote both economic growth and workers’ well-being.

REFERENCES

- Adams Zoe and Deakin Simon. 2014. “Institutional Solutions to Precariousness and Inequality in Labour Markets.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 52: 779–809. [Google Scholar]

- Beck Ulrich. 2000. The Brave New World of Work (translated by Patrick Camiller). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breman Jan and van der Linden Marcel. 2014. “Informalizing the Economy: The Return of the Social Question at a Global Level.” Development and Change 45: 920–940. [Google Scholar]

- Devine Ethan. 2013. “The Slacker Trap.” The Atlantic, May (https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/05/the-slacker-trap/309285; accesssed October 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Robert J. 2016. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker Jacob S. 2011. “The Institutional Foundations of Middle-Class Democracy” Progressive Governance, Oslo: 33–37. (http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=3998&title=The+institutional+foundations+of+middle-class+democracy; accessed September 10, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Hall Peter A. and David Soskice (editors). 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hijzen Alexander and Menyhert Balint. 2016. “Measuring Labour Market Security and Assessing its Implications for Individual Well-Being”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 175, OECD Publishing, Paris: ( 10.1787/5jm58qvzd6s4-en; accessed June 21, 2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horning Rob. 2012. “Precarity and Affective Resistance.” The New Inquiry, February 14 (http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/marginal-utility/precarity-and-affective-resistance; accessed December 13, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New Yorkn NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. 2018. Precarious Lives: Job Insecurity and Well-Being in Rich Democracies. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. and Hewison Kevin. 2013. “Precarious Work and the Challenge for Asia.” American Behavioral Scientist 57: 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Katz Lawrence F. and Krueger Alan B.. 2015. “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; (http://www.nber.org/papers/w22667; accessed February 3, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Korpi Walter. 1983. The Democratic Class Struggle. London, UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi Walter. 1985. “Developments in the Theory of Power and Exchange.” Sociological Theory 3: 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; (http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/in-it-together-why-less-inequality-benefits-all_9789264235120-en; accessed February 3, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski Martin, Kalleberg Arne L. and Rindfuss Ronald R.. 2015. “Contingent work rising: Implications for the timing of Marriage in Japan.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 77: 1039–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi Karl. 1957. [1944] The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. New York, NY: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer Stefani. 2009. “The Social Consequences of Insecure Jobs.” Social Indicators Research 93: 527–547. [Google Scholar]

- Schram Sanford F. 2015. The Return of Ordinary Capitalism: Neoliberalism, Precarity, Occupy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett Richard. 2000. The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. New York, NY: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens John D. 1979. The Transition from Capitalism to Socialism. London, UK: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz Joseph E., Sen Amartya, and Fitoussi Jean-Paul. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Commission on the Measurement of Economic performance and Social Progress: France: (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/118025/118123/Fitoussi+Commission+report; accessed October 7, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Supiot Alain. 2001. Beyond Employment: Changes in Work and the Future of Labour Law in Europe. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen Kathleen. 2014. Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity. New York, NY: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Therborn Göran. 2013. The Killing Fields of Inequality. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vosko Leah F. 2010. Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]