Abstract

The addition of the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to the DSM-5 has spurred investigation of its genetic, neurobiological, and treatment response correlates. In order to reliably assess the subtype, we developed the Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale (DSPS, Wolf et al., 2017), a 15-item index of dissociative features. Our initial investigation of the dichotomous DSPS lifetime items in a veteran epidemiological sample demonstrated its ability to identify the subtype, supported a three-factor measurement structure, distinguished the three subscales from the normal-range trait of absorption, and demonstrated the greater contribution of derealization and depersonalization symptoms relative to other dissociative symptomatology. In this study, we replicated and extended these findings by administering self-report and interview versions of the DSPS, and assessing personality and PTSD in a sample of 209 trauma-exposed veterans (83.73% male, 57.9% with probable current PTSD). Results replicated the three-factor structure using confirmatory factor analysis of current symptom severity interview items, and the identification of the dissociative subtype (via latent profile analysis). Associations with personality supported the discriminant validity of the DSPS and suggested the subtype was marked by tendencies towards odd and unusual cognitive experiences and low positive affect. Receiver operating characteristic curves identified diagnostic cut-points on the DSPS to inform subtype classification, which differed across the interview and self-report versions. Overall, the DSPS performed well in psychometric analyses, and results support the utility of the measure in identifying this important component of posttraumatic psychopathology.

Keywords: dissociative subtype, PTSD, DSM-5, psychometric, derealization/depersonalization

Introduction

The literature concerning the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has grown tremendously in the relatively short period since it was introduced in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5, APA, 2013). The dissociative subtype of PTSD is defined in DSM-5 as meeting full criteria for PTSD plus exhibiting comorbid symptoms of derealization and/or depersonalization; the estimated prevalence of the subtype ranges from 12–30% across trauma-exposed samples (Armour, Elklit, Lauterbach, & Elhai, 2014; Armour, Karstoft, & Richardson, 2014; Blevins, Weathers, & Witte, 2014; Steuwe, Lanius, & Frewen, 2012; Wolf, Lunney, et al., 2012), including 4 – 30% in trauma-exposed veteran samples specifically (Armour, Karstoft, et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2017; Wolf, Lunney, et al., 2012; Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012), which highlights the importance of studying dissociative phenomena among veterans. There are now at least 11 published studies that used latent profile or class analysis to identify a dissociative subtype of PTSD (Armour, Elklit, et al., 2014; Armour, Karstoft, et al., 2014; Bennett, Modrowski, Kerig, & Chaplo, 2015; Blevins et al., 2014; Frewen, Brown, Steuwe, & Lanius, 2015; Hansen, Műllerová, Elklit, & Armour, 2016; Műllerová, Hansen, Contractor, Elhai, & Armour 2016; Ross, Baník, Dědová, Mikulášková, & Armour, 2017; Steuwe et al., 2012; Wolf, Lunney, et al., 2012; Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012). A qualitative review also supported the replicability of the subtype structure (Armour, Műllerová, & Elhai, 2016).

We have previously suggested (Dutra & Wolf, 2016; Wolf, Lunney, & Schnurr, 2016) that distinguishing the dissociative subtype of PTSD from PTSD without dissociation is critical for both research and clinical purposes. Specifically, the subtype may be associated with a unique etiology, neurobiology, and clinical course, and failure to identify the subtype may impede efforts to identify predictors and correlates of PTSD because phenotypic heterogeneity associated with the dissociative subtype would not be accounted for at all. A number of studies support this hypothesis. For example, a genome-wide association study of the symptoms that define the dissociative subtype of PTSD identified genetic markers that were associated with these symptoms but that were unrelated to the core PTSD symptoms (Wolf et al., 2014). A growing body of imaging studies have raised the possibility that the dissociative subtype is associated with a neurobiological signature defined by increased top-down processing from frontal cortical regions and reduced limbic responsiveness (the opposite pattern from that observed for those with PTSD symptoms without dissociation; Frewen & Lanius, 2006; Lanius, Bluhm, Lanius, & Pain, 2006; Lanius, Brand, Vermetten, Frewen, & Spiegel, 2012; Lanius et al., 2010; Lanius et al., 2002). The subtype has been shown to be associated, in some studies, with greater exposure to sexual (Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012) and childhood (Steuwe et al., 2012) trauma and to co-occur with major depression and anxiety, as well as borderline and avoidant personality disorders (Lanius et al., 2012; Steuwe et al., 2012; Wolf, Lunney, et al., 2012).

Identification of the dissociative subtype is also thought to have substantial clinical relevance, as it is hypothesized that individuals with the subtype may respond less favorably to standard PTSD therapies. The literature on this has been mixed, with some evidence suggesting subtle but significant effects of the subtype on PTSD psychotherapy (Wolf et al., 2016) or psychopharmacological treatment response (Burton, Feeny, Connell, & Zoellner, 2018), others suggesting that those with the subtype may respond better to specific treatment approaches (i.e., raising the possibility of treatment matching; Cloitre, Petkova, & Wang, 2012; Resick, Suvak, Johnides, Mitchell, & Iverson, 2012), and still other studies reporting no effects of dissociation on treatment response, traditionally operationalized as a dissociation X time effect (Burton et al., 2018; Cloitre et al., 2012; Halvorsen, Stenmark, Neuner, & Nordahl, 2014; Resick et al., 2012; see also Dutra & Wolf, 2016 for a more complete review). Studies evaluating the etiology, clinical correlates, and treatment effects of the subtype highlight the need for continued research on this unique PTSD presentation, and the need to reliably and efficiently assess it.

We recently developed the Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale (DSPS, Wolf et al., 2017), a 15-item index of a range of dissociative features, including those that define the dissociative subtype of PTSD according to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). It includes one subscale that corresponds directly to the DSM-5 criteria (i.e., the Derealization/Depersonalization subscale) as well as scales measuring two other dimensions of dissociation that tend to co-occur with PTSD and may be of clinical importance (i.e., the Loss of Awareness and Psychogenic Amnesia subscales). The inclusion of multiple scales within the inventory is important because there are many manifestations of dissociation including derealization, depersonalization, dissociated identity, fugue states, perceptual disturbances, loss of awareness, and loss of memory for traumatic and day-to-day experiences (Spiegel & Cardeña, 1991). These varying presentations should be distinguished from one another, as studies have suggested that symptoms of derealization and depersonalization are unique in their subtype structural association with PTSD, whereas other forms of dissociation tend to be linearly related to PTSD symptom severity (Armour et al., 2016; Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2017). Thus, it is important to assess dissociative symptoms broadly and identify the symptoms that define the subtype specifically.

The DSPS was previously administered as a self-report inventory and includes an assessment of both lifetime (dichotomous) and current (dimensional) symptoms, with the latter including scales for symptom frequency and intensity. Our initial publication (Wolf et al., 2017) describing the development of the DSPS yielded the following findings: (a) three factors explained the majority of the variance and covariance in the lifetime items (per exploratory factor analyses), with the three factors aligning with the aforementioned subscales; (b) the lifetime items replicated the previously observed dissociative subtype structure (via latent profile analysis); (c) the lifetime Derealization/Depersonalization subscale contributed most to subtype membership (relative to other types of dissociative symptoms); and (d) the lifetime subscales were internally consistent and evidenced discriminant validity in comparison to trait absorption, as defined by Tellegen and Waller (2008). Of course, our initial study had limitations. While we drew from a large, nationally-representative sample of trauma-exposed veterans, the data were collected online and prevalence estimates of current PTSD and dissociative symptoms were too low to permit evaluation of the current items, so only dichotomous lifetime items were analyzed. There was also no independent metric of the dissociative subtype classifications against which to compare DSPS group assignments, and assessment of discriminant validity was limited.

The purpose of this study was to address these limitations by focusing on interview-based assessments of current DSPS items in a sample of veterans with substantial PTSD symptoms. We also aimed to develop cut-points for identification of the subtype and compare its associations with a broad range of indices of temperament and personality. More specifically, our aims were to: (1) examine the replicability of the three-factor structure of the DSPS current severity interview items using confirmatory factor analysis; (2) test for a distinct dissociative subtype using latent profile analysis; (3) further evaluate the reliability and validity of the DSPS, including comparison of the scale when administered as a self-report versus interview and a broader assessment of its discriminant validity; and (4) develop cut-points on the DSPS to determine current caseness for the subtype, as indicated by dissociation items embedded in the well-established Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS, Weathers et al., 2013).

To examine the discriminant validity of the DSPS subscales, we evaluated their correlations with omnibus personality traits as measured by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF; Ben-Porath & Tellegen, 2008) and by the Absorption scale on the Brief Form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ-BF, Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002). We were particularly interested in testing for discrimination between the dissociative subtype and the broad-range personality trait of demoralization, which has been shown to pervade psychopathology (Tellegen et al., 2003). We also wanted to test the measure’s ability to discriminate serious psychopathology symptoms from trait absorption (i.e., a tendency towards an enveloping and exclusive engagement with environmental, emotional, sensory, or cognitive experiences; Tellegen & Waller, 2008), which has previously been shown to unduly influence other measures of dissociation (Giesbrecht, Lynn, Lilienfeld, & Merckelbach, 2008). A related goal was to examine the contribution of temperament to the subtype (and as compared to PTSD without dissociation).

These aims were evaluated in a sample of 209 male and female trauma-exposed veterans who screened positive for PTSD during a telephone screen. We hypothesized that the DSPS would evidence a three-factor structure defined by derealization/depersonalization, loss of awareness, and psychogenic amnesia and that subtype analysis of current DSPS items would reveal a latent class defined by high PTSD symptoms and marked symptoms of derealization and depersonalization distinguishable from a class defined by high PTSD symptoms alone. We hypothesized that the DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization subscale would correctly classify the subtype as compared to CAPS-based determinations and would evidence divergent patterns of association with trait negative emotionality, demoralization, and absorption.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited through three sources: (1) a recruitment database of veterans interested in participating in research in our Center; (2) flyers posted in the medical center; and (3) standardized invitations to patients in group therapy in a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) PTSD clinic. Three hundred seventeen potential participants were screened via telephone to determine eligibility, i.e., veteran status, age 18+, and a positive screen for current PTSD diagnosis over the telephone using the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5); PTSD symptoms were further evaluated for enrolled participants. Of these 317 veterans, 260 screened positive for PTSD, and 215 agreed to participate. Of the 215 enrolled participants, six failed to complete the protocol and were excluded from analyses, yielding a final sample size of 209: 175 male (83.7%) and 34 female veterans. Self-reported race and ethnicity were as follows: 65.07% white, 29.67% African American or black, 5.26% American Indian or Alaska Native, 2.87% unknown, 1.91% Asian, and 1.44% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; 4.78% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino (self-reported race categories were not exclusive; therefore, percentages sum to over 100). The sample ranged in age from 21–75 years (M = 53.79 years; SD = 11.39). The main war eras for the sample were Vietnam (39.23%), other (25.36%), Operation Iraqi Freedom/ Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation New Dawn (22.97%), and Operation Desert Storm (11.48%).

The study lasted about three hours. All self-report measures were completed via laptops. Interviews were conducted by research assistants who underwent extensive training by the senior author. All interviews were videotaped for reliability and assessment fidelity purposes, and approximately 30% of dissociation assessment recordings were viewed and discussed in team meetings. The study was approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System IRB and all participants provided written informed consent. Participants were compensated at the end of the study.

Measures

Trauma Assessment from the National Stressful Events Survey (NSES; Kilpatrick, Resnick, Baber, Guille, & Gros, 2011).

The trauma component of the NSES was administered as an interview to examine exposure to traumatic events pre-military (physical or sexual abuse, serious accidents, fire, sudden death of a close relative or friend, natural or man-made disaster, terrorist attack), military (military sexual trauma [MST], combat exposure, military training accidents, or other stressful events related to military service), and post-military (same events listed for pre-military). Participants were asked to identify their “worst” traumatic experience.

Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale (DSPS; Wolf et al., 2017)1.

The DSPS is a 15-item scale that measures the presence of lifetime and past-month (current) symptoms, as well as the frequency and intensity of the latter. Items follow a branching structure, starting with dichotomous responses to lifetime symptoms. Next, endorsed items are probed for past month presence. If positive, then past month symptom frequency (on a 4-point scale; once/twice a month to daily/almost every day) and symptom intensity (on a 5-point scale; not very strong to extremely strong) are assessed. As described in Wolf et al. (2017), item content included multiple examples of each type of dissociative experience to provide broad content coverage, with items assessing derealization, depersonalization, psychogenic amnesia, loss of awareness, and loss of memory for everyday experiences. In our previous study of veterans, internal consistency ranged from α = .74 - .79 across the three lifetime subscales, and α = .85 for all 15 lifetime items; the lifetime items also showed good discrimination from trait absorption and from PTSD symptom severity (Wolf et al., 2017). The DSPS was administered as an interview and videotaped for inter-rater reliability purposes. The DSPS was also administered as a self-report measure to a subset of participants (n = 92) to examine the reliability of the DSPS across the two modalities. In the interview format, assessors ruled out symptoms that occurred only under conditions of substance or medication use or extreme fatigue. Intraclass correlation coefficients, calculated with two-way mixed models with single measures, for current item severity ratings, based on independent secondary ratings of 29% (n = 60) of the videotaped interviews, were r = .90, .86, .96 for the Derealization/ Depersonalization, Loss of Awareness, and Psychogenic Amnesia subscales, respectively.

DSM-5 PTSD Symptom Assessment (adapted from Weathers et al., 2014 and Kilpatrick et al., 2011).

We utilized item content from the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2014) in combination with the structured response options for symptom assessment on the NSES (Kilpatrick et al., 2011) to assess PTSD. Items were anchored to the participant’s self-identified “worst” traumatic experience. Both lifetime and current DSM-5 PTSD symptoms were assessed. The PCL-5 consists of 20 items, each assessing the severity of DSM-5 PTSD criteria in the past month on a scale from 0–4. In studies of veterans, the PCL-5 evidenced strong test-retest reliability over a one-month interval, and showed expected patterns of convergent (e.g., with indices of psychosocial functioning) and discriminant (e.g., with a measure of alcohol misuse) validity (Bovin et al., 2016). Dimensional scores on the PCL-5 have demonstrated strong associations with interviewer-rated CAPS-5 severity scores (Weathers et al., 2018)

Based on our past research with the NSES, we adapted the response options to include evaluation of lifetime symptomatology and to better ensure that reports of current symptoms were anchored to the past month (Kilpatrick et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2013). Using the standard PCL-5 item phrasing, we asked (via interview) if the symptom had ever been present and if yes, we asked if the symptom had been present in the past month. If present in the past month, we asked participants to rate past month symptom severity on the standard PCL-5 response scale. Chronbach’s alpha coefficients for past month symptom severity ratings was α = .87, and for the four symptom clusters (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal) were α = .79, .59, .77, and .63, respectively. Current probable PTSD diagnostic status was defined by endorsement of the requisite number of symptoms in each PTSD symptom cluster per DSM-5, with symptom presence defined by a rating of “moderate” severity or greater (e.g., a score ≥ 2 on the 0–4 scale; Bovin et al., 2016).

Absorption Scale from the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire–Brief Form (MPQ-BF; Patrick et al., 2002).

We administered the Absorption scale from the MPQ-BF to assess the discriminant validity of dissociative features on the DSPS from this trait. The scale is comprised of 12 true/false items, assessing the capacity to be focused and absorbed (both cognitively and emotionally) in sensory stimuli, surroundings, internal experiences, and activities. The scale also inventories altered mental states, and the experience of imaginative and “self-altering” events, including those of a religious nature. Prior studies suggest that it is strongly correlated with the Absorption scale on a substantially longer version of the MPQ and that it evidences discrimination from measures of generalized distress and negative affect (Patrick et al., 2002). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this sample was α = .76.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF; Ben-Porath & Tellegen, 2008; Tellegen & Ben-Porath, 2008).

The MMPI-2-RF is a 338 true-false item inventory assessing a diverse range of personality, temperament, and psychopathology domains. The MMPI-2-RF includes three Higher-Order (H-O) scales: Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction (EID) which assesses mood and affect problems, Thought Dysfunction (THD) which assesses disordered thinking and aberrant perceptual experiences, and Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction (BXD) which measures impulsive, rule-breaking behavior, including substance misuse. It also includes nine restructured clinical scales (RCs), which reflect more unidimensional facets of the three H-O scales, adapted from the original Clinical Scales on the MMPI-2. These nine RC scales include: RCd: Demoralization (a sense of dissatisfaction, poor self-agency); RC1: Somatic Complaints (physical health complaints likely to be of psychological origin); RC2: Low Positive Emotions (anhedonia, reduced social affiliation); RC3: Cynicism (distrustful beliefs, low opinion of others); RC4: Antisocial Behavior (misconduct, impulsivity); RC6: Ideas of Persecution (persisting beliefs that others pose a threat); RC7: Dysfunctional Negative Emotions (maladaptive anxiety, irritability; high levels of arousal and emotional intensity); RC8: Aberrant Experiences (unusual perceptual and cognitive symptoms); and RC9: Hypomanic Activation (aggression, heightened energy, grandiosity). The MMPI-2-RF also includes several validity scales that assess response style consistency, random responding, and over- and under-reporting (see below for applied cut-scores). The MMPI-2-RF was developed using classical test construction methods and has undergone rigorous assessment of its reliability and validity in inpatient, outpatient, veteran, and community samples, with scales showing expected patterns of association with measures of psychopathology and temperament, evidencing adequate test-retest reliability and internal consistency (Tellegen & Ben-Porath, 2008).

Derealization and Depersonalization items from the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., 2013, 2018).

To validate diagnostic classifications of the dissociative subtype of PTSD, we administered two items from the 30-item CAPS-5, a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-5 PTSD. These items assessed the severity of depersonalization and derealization symptoms on a scale from 0–4. Interviews were videotaped for reliability and to prevent rater drift. Inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) based on 32% of the CAPS-5 interviews for the combined dissociation severity score across the two items was r = .76, calculated with a two-way mixed model with single measures. Though the CAPS-5 has been extensively validated (Weathers et al., 2018) and is considered the “gold standard” in PTSD assessment, no study to our knowledge has conducted a psychometric investigation of the dissociative symptoms specifically.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence of DSPS Item Endorsement.

We assessed current DSPS interview items using a rule of frequency ≥ 1 and intensity ≥ 3, i.e., occurring at least once or twice in the past month with at least moderate symptom severity, following prior work (Miller et al., 2013). We compared item endorsement as a function of probable PTSD diagnostic status using chi-square.

Factor Structure of DSPS Item Severity Scores.

Next, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the DSPS current symptom severity interview scores based on the three-factor model that was identified in our prior exploratory factor analysis of the lifetime DSPS items (Wolf et al., 2017). Specified factors corresponded to Derealization/Depersonalization, Loss of Awareness, and Psychogenic Amnesia. The CFA was conducted with the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) to account for non-normally distributed data. Model fit was evaluated using standard fit indices and guidelines (Hu & Bentler, 1999), including χ2, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), confirmatory fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Comparison across competing models was examined via Δ χ2 and the relative values of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; lower values are preferred for this statistic).

Examination of Reliability and Discriminant Validity.

We calculated subscale summary scores on the DSPS interview corresponding to the CFA structure and evaluated internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) and cross-method reliability, by comparing scores on the current symptom severity subscales across the interview and self-report formats using correlation. We also evaluated the correlations between each interview-based DSPS subscale and PTSD symptom cluster subscales and between the DSPS subscales and the MPQ-BF index of absorption, and the MMPI-2-RF H-O and RC scales.

For all MMPI-2-RF analyses, we eliminated participants (n = 50) based on invalid responses on the validity scales. Specifically, following Arbisi, Polusny, Erbes, Thuras, and Reddy (2011), we excluded participants at the following thresholds: Cannot Say (CNS) ≥ 18 (n = 3), VRIN T-score ≥ 80 (n = 7), TRIN T-score ≥ 80 (n = 17), or Fp-r T-score ≥ 100 (n = 32). Some participants scored above more than one threshold, thus total n exceeds 50. These cut-scores align with those defined in the manual by Ben-Porath & Tellegen (2008), except that we did not use F-r to eliminate invalid response profiles (consistent with Arbisi et al., 2011), as (a) F-r scores are, on average, substantially elevated in PTSD samples (Marion, Sellbom, & Bagby, 2011); (b) F-r does not add incrementally beyond Fp-r in differentiating PTSD patients from those instructed to fake PTSD symptoms (Marion et al., 2011); and (c) Fp-r is generally superior than F-r in differentiating over-reporting from true psychiatric symptoms in PTSD and related psychiatric samples (Marion et al., 2011; Sellbom & Bagby, 2010). Consistent with our prior research (Miller et al., 2012), these subjects were not eliminated from analyses that did not include the MMPI-2-RF, as all other analyses were focused on interview-based assessments (e.g., of dissociation and PTSD) and thus would not be vulnerable to the same types of over-reporting biases as a lengthy self-report measure. We also re-ran our primary analyses that did not involve the MMPI-2-RF scales without these 50 subjects and found the overall pattern of results to be near identical to that reported in the main text when these 50 subjects were included. This suggests that eliminating these subjects altogether was not indicated.

Identification of Subtype Membership and of its Correlates.

Analyses then focused on the utility of the DSPS to adequately capture the dissociative subtype. To do so, we first conducted a latent profile analysis (LPA) using the current PTSD symptom cluster severity scores and the DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization interview severity summary scores as indicators of class membership. We began with a three-class solution and tested the relative fit of competing class solutions. All LPAs were evaluated using standard criteria, i.e., BIC, sample-size adjusted BIC (aBIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), Lo-Mendell-Rubin–adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMRA), bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and entropy (Nylund, Asparouhov & Muthén, 2007) in concert with model interpretability and class size. All latent variable analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012).

We evaluated differences in demographic and trauma exposure variables across DSPS-based subtype classifications using ANOVA and chi-square. We also conducted regression analyses to evaluate associations between personality and dissociative subtype membership. To do so, we conducted two sets of multiple regressions using posterior probability scores indicating likelihood of membership in the dissociative subtype or the high PTSD group, per the DSPS LPA results. In the first step of each regression, we controlled for age and sex, and in the second step of the regression we entered either the three MMPI-2-RF H-O scales or the 9 RCs.

Identification of DSPS Cut-Points for the Dissociative Subtype.

We conducted an unrestricted LPA of the PTSD symptom severity cluster scores and CAPS derealization and depersonalization current summary scores in order to extract most likely class-membership using a CAPS-based assessment of the subtype and to compare these class determinations against the interview-based DSPS-scores via receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCs). This analysis examined how current item endorsement on the DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization scale (using the aforementioned definition of symptom presence/absence) was associated with the CAPS-based LPA determination of membership in the dissociative class as compared to the high PTSD symptom severity class without dissociation. We evaluated area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive power, and accuracy for DPSP item endorsement cut-points to maximize the ability to correctly predict dissociative subtype caseness. We used chi-square analyses to determine how the best DSPS threshold from the ROC performed in comparison to the CAPS-based LPA determination of subtype membership.

Comparison of DSPS interview and Self-Report Cut-Score Performance

We applied the dissociative subtype cut-score identified in analyses conducted with the interview administration of the DSPS to the self-report administration of the measure. We conducted McNemar tests in order examine concordance between the DSPS interview and self-report formats for identifying individuals with the dissociative subtype, as well as between the DSPS self-report based dissociative group and the CAPS-based LPA dissociative group. We also conducted an ROC on the self-report scale to maximize prediction of subtype caseness.

Results

Prevalence of DSPS Item Endorsement and other Relevant Characteristics

Current dissociative items on the DSPS interview were endorsed by a minority of the sample (symptom presence defined by frequency ≥ 1 and intensity ≥ 3; Table 1). The most commonly endorsed item was #11 (being in a daze or a fog; 28.7%); the least commonly endorsed was #9 (feeling as if one’s body is strange; 4.8%). All DSPS items were more prevalent among those with probable PTSD per the PCL-5 interview administration (57.9% of the sample) compared to those without current PTSD (42.1%; Table 1). The mean number of different types of trauma endorsed was 6.8 (SD: = 4.36, range = 0–22); this included 58.1% of the sample endorsing pre-military trauma, 89.3% endorsing military-related trauma, and 67% endorsing post-military trauma. See Supplementary Table 1 for endorsement rates on the self-report DSPS.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Current Dissociative Symptoms in the Full Sample and by Probable PTSD Diagnostic Status

| DSPS Item (Interview) | All (n = 209) |

PTSD + (n = 121) |

PTSD − (n = 88) |

p | Effect size (φ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Disconnected from body | 10% | 16.5% | 1.1% | < .001 | .25 |

| 2. Checked out | 21.5% | 30.6% | 9.1% | < .001 | .26 |

| 3. Outside body | 12% | 19% | 2.3% | < .001 | .25 |

| 4. Lost time | 13.4% | 22.3% | 1.1% | < .001 | .31 |

| 5. Not recognize self | 5.7% | 9.1% | 1.1% | .015 | .17 |

| 6. Strange or unfamiliar place | 8.6% | 13.2% | 2.3% | .005 | .19 |

| 7. Body not feel real | 6.2% | 10.7% | 0% | .001 | .22 |

| 8. World not seem real | 8.1% | 13.2% | 1.1% | .002 | .22 |

| 9. Body is strange or unfamiliar | 4.8% | 8.3% | 0% | .006 | .19 |

| 10. Lost or disoriented in familiar place | 15.3% | 23.1% | 4.5% | < .001 | .25 |

| 11. Daze or fog | 28.7% | 41.3% | 11.4% | < .001 | .33 |

| 12. World is a movie | 11.5% | 17.4% | 3.4% | .002 | .22 |

| 13. Not remember how got somewhere | 11% | 18.2% | 1.1% | < .001 | .27 |

| 14. Trouble remembering trauma details | 20.2% | 27.3% | 10.2% | .003 | .21 |

| 15. Should remember more about trauma | 22.5% | 32.2% | 9.1% | < .001 | .27 |

Note. DSPS = Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. p-value associated with χ2 test with n = 209 and df = 1; φ = phi coefficient. Parallel analyses based on the self-report administration of the DSPS are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Factor Structure of DSPS Item Severity Scores

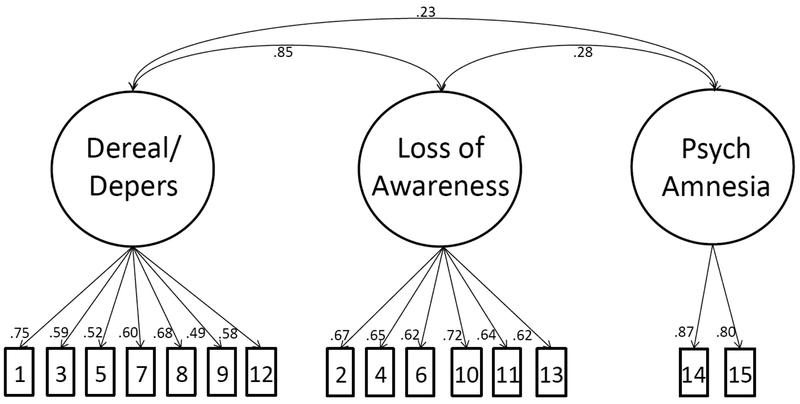

CFA evaluated if the latent structure of the measure corresponded with results of our prior exploratory factor analysis (Wolf et al., 2017). The three-factor model of the current DSPS interview item severity scores fit the data well, with all fit indices consistent with adequate (CFI and TLI) to good (RMSEA, SRMR) model fit: χ2 (n = 209, df = 87) = 124.24, p = .005, BIC = 12685, RMSEA = .045, CFI = .92, TLI = .90, SRMR = .058. Items loaded significantly on their respective factors (all p < .001) and in the range of .58 to .87 (Figure 1). Factor correlations suggested a strong association between the Derealization/Depersonalization and Loss of Awareness factors (r = .85), but weak associations between these two factors and the Psychogenic Amnesia factor (rs = .23 and .28, respectively; Figure 1). Based on this, we tested a two-factor model that combined the derealization/depersonalization and loss of awareness interview items onto a single factor. While this model achieved adequate fit, χ2 (n = 209, df = 89) = 134.34, p = .001, BIC = 12700, RMSEA = .049, CFI = .90, TLI = .89, SRMR = .061, both the BIC value and the Δ χ2 test supported the superiority of the three-factor model (Δ χ2 = 6.83, Δ df = 2, p < .05) and thus the three-factor structure was retained in subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Figure shows the results of the confirmatory factor analysis of the current dissociation severity items on the Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale (interview administration). The indicator numbers represent the item numbers and are defined in Table 1. All items loaded significantly on their respective factors at the p < .001 level. Dereal/Depers = derealization/depersonalization; Psych = psychogenic.

Examination of Reliability and Discriminant Validity

Internal reliability of the current severity interview ratings for items contributing to the three DSPS subscales was excellent: Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for Derealization /Depersonalization α = .79; Loss of Awareness α = .81, and Psychogenic Amnesia α = .82. Internal reliability of the current severity self-report ratings were also excellent: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for Derealization/Depersonalization α = .90, Loss of Awareness α = .92, and Psychogenic Amnesia α = .92. Subscale correlations for the measure when administered via interview versus self-report for the subset of 92 veterans who completed both modes of administration yielded large magnitude effects: Derealization/ Depersonalization r = .87, Loss of Awareness r = .90, Psychogenic Amnesia r = .85.

Bivariate correlations between current DSPS (interview) subscale and PTSD symptom and severity scores were generally consistent with small-to-medium effect sizes (Table 2). The Psychogenic Amnesia subscale tended to evidence the weakest association with each PTSD variable while the Derealization/Depersonalization and Loss of Awareness subscales evidenced somewhat stronger and largely equivalent patterns of association with PTSD severity. Bivariate correlations between the three DSPS interview subscales and the MMPI-2-RF scales and MPQ-BF Absorption scale are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Of the MMPI-2-RF H-O scales, EID was significantly associated with all three DSPS subscales; THD was only associated with Derealization/Depersonalization and Loss of Awareness. Of the MMPI-2-RF RCs, RCd, RC1, RC2 and RC7 were all significantly associated with the three DSPS subscales; RC6 and RC8 were associated with Derealization/Depersonalization and Loss of Awareness. All correlations were in the small to medium effect size range (with the majority of rs < .30), suggesting strong discriminant validity for the DSPS. On face value, the three strongest associations were between THD, RC1, and RC8 and Loss of Awareness (rs = .42, .45 and .43, respectively), which was also the DSPS subscale with the strongest association with PTSD (Table 2). Absorption scores on the MPQ-BF were significantly correlated with medium magnitudes of association with DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization (r = .39) and Loss of Awareness (r = .37) subscales.

Table 2.

Correlations between Current DSPS Interview Subscales, and PTSD Symptoms

| DSPS Subscale | PTSD Sev | B Sx Sev | C Sx Sev | D Sx Sev | E Sx Sev | CAPS Dereal/Depers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dereal/Depers | .47*** | .36*** | .33*** | .41*** | .36*** | .75*** |

| Loss of Awareness | .52*** | .41*** | .32*** | .43*** | .47*** | .69*** |

| Psych Amnesia | .36*** | .21** | .18** | .41*** | .27*** | .16* |

Note. DSPS = Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; sev = severity; sx = symptom; Dereal/Depers = derealization/depersonalization; psych = psychogenic; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; B = Cluster B (Intrusion symptoms); C = Cluster C (Avoidance symptoms); D = Cluster D (Negative alternations in cognitions and mood); E = Cluster E (Alterations in arousal and reactivity).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Identification of Subtype Membership and of its Correlates

LPA was next conducted to determine if the DSPS could identify the hypothesized class structure with a unique dissociative subtype. A three-class LPA with no parameter constraints on the PTSD symptom cluster and DSPS interview subscale severity scores converged on a solution with a replicated loglikelihood value and the BLRT p-value (p < .001) suggested that this three-class solution provided better fit than would a two-class solution (Supplementary Table 3). In this model, 42.1% (n = 88) were assigned to the low/moderate PTSD symptom class, 49.3% (n = 103) to the high PTSD symptom class, and 8.6% (n = 18) to the dissociative class (Supplementary Figure 1). We compared the three-class model with a four-class solution and found that while the BIC, AIC, and aBIC were lower in the four-class solution, the solution was problematic as the fourth class was comprised of just 5.3% of the sample, raising doubt about the generalizability of results. Based on this, and the extant literature on the dissociative subtype of PTSD to date, we proceeded with the three-class solution.

An omnibus chi-square test revealed differences in DSPS class assignment as a function of sex: χ2 (2, n = 209) = 7.720, p = .021, φ = .192. Given that our primary interest was in the comparisons between the high PTSD class and the dissociative class, we re-ran this analysis restricting the sample to these two groups and found that a greater percentage of women (30.4% of the 23 women) were assigned to the dissociative subtype relative to men (11.2% of the 98 men; χ2 [1, n = 121] = 5.429, p = .02, φ = −.212). No other significant group differences emerged across age (using t-tests and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance: all p > .05) or race (when comparing self-identified white participants to self-identified non-white participants).

A one-way ANOVA with DSPS class membership as the group variable revealed that the total number of traumatic events across the lifetime did not differ across the three groups (Low/moderate: M = 6.25, SD = 4.183; High PTSD: M = 7.223, SD = 4.417; Dissociative: M = 7.556, SD = 4.643; F (2, 206) = 1.415, p = .245; Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance: F (2, 206) = 1.13, p = .325). Significant differences emerged when we examined childhood sexual trauma, childhood abuse, MST, and any lifetime sexual trauma (i.e., the types of trauma hypothesized to be strongly associated with dissociation) as a function of group assignment: Omnibus chi-square analyses suggested that exposure to any sexual trauma across the lifetime, and to MST specifically, was associated with DSPS subtype classification: χ2 (2, 209) = 23.348, p < .001, φ = .334, χ2 (2, 209) = 17.779, p < .001, φ = .292, respectively. We then limited the analysis to those assigned to the high PTSD and dissociative classes (i.e., the comparison of interest) and found that individuals within the dissociative class were more likely to report MST compared to those in the high PTSD class (55.6%, or 10/18 in the dissociative class, compared to 30.1%, or 31/103 in the high PTSD class, p = .035, φ = .191), but there were no differences in the percentage of participants reporting lifetime exposure to sexual trauma. Of note, of those assigned to the dissociative (n = 18) or high (n = 103) PTSD classes, a greater percentage of women (78.3%; n = 18) compared to men (23.5%; n = 23) reported exposure to MST: χ2 (1, n = 121) = 24.96, p < .001). There were no omnibus group differences in exposure to childhood abuse or childhood sexual abuse across the three classes (all p ≥ .05). Prevalence of trauma exposure as a function of subtype membership is reported in Supplementary Table 4.

We conducted regressions to examine MMPI-2-RF predictors of probability of class assignment to the high PTSD versus the dissociative class (Table 3), controlling for age and sex in Step 1 of the equations. Step 1 accounted for 9.6% (p < .001) of the variance in the dissociative class, with sex driving the effect (β = −.29, p < .0001), such that women, on average, evidenced greater dissociative symptoms. No such effect was present when predicting the high PTSD class. Examining H-O predictors of probability of dissociative class membership revealed that only THD evidenced a significant association with the subtype (β = .24, p < .01), with Step 2 of the model accounting for 7.8% of incremental variance. In the model predicting likelihood of membership in the high PTSD class, EID and THD emerged as significant predictors (β = .38, p < .001; β = .23, p < .01, respectively), with Step 2 accounting for 31.2% of incremental variance. Analyses were repeated with the RCs, revealing that RC2 and RC8 were associated with probability of dissociative class membership (β = .29, p < .05; β = .31, p < .01, respectively), while RCd was associated with probability of high PTSD class membership (β = .42, p < .01).

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regressions Predicting High PTSD Class vs. Dissociative Subtype Posterior Probability Scores

| DSPS Posterior Probability Scores: High PTSD |

DSPS Posterior Probability Scores: Dissociative |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 |

| Step 1 (Both Models) | .000 | .096*** | ||

| Age | .014 | −.079 | ||

| Sex | .014 | −.293*** | ||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Step 2 | .312*** | .078** | ||

| EID | .382*** | .104 | ||

| THD | .226** | .244** | ||

| BXD | .116 | −.159 | ||

| Model 2 | ||||

| Step 2 | .340*** | .134** | ||

| RCd | .415** | −.237 | ||

| RC1 | .167 | .012 | ||

| RC2 | −.124 | .291* | ||

| RC3 | −.010 | −.105 | ||

| RC4 | .118 | −.096 | ||

| RC6 | .118 | −.002 | ||

| RC7 | .021 | .091 | ||

| RC8 | .080 | .308** | ||

| RC9 | −.073 | .020 | ||

Note. The interview version of the DSPS was analyzed to maximize sample size. DSPS = Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale; H-O = Higher-Order; EID = Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction; THD = Thought Dysfunction; BXD = Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction; RC = Restructured Clinical; RCd = Demoralization; RC1 = Somatic Complaints; RC2 = Low Positive Emotions; RC3 = Cynicism; RC4 = Antisocial Behavior; RC6 = Ideas of Persecution; RC7 = Dysfunctional Negative Emotions; RC8 = Aberrant Experiences; RC9 = Hypomanic Activation;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Step 1 was identical for models 1 and 2, so is only displayed once in the table.

Identification of DSPS Cut-Points for the Dissociative Subtype

The three-class LPA based on PTSD symptom cluster severity scores plus the CAPS dissociation item severity score yielded three classes that were similar to the model based on the DSPS interview: 42.1% were assigned to the low/moderate PTSD group, 43.1% to the high PTSD group, and 14.8% to the dissociative class (Supplementary Table 3). The ROC based on the number of endorsed current DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization interview subscale items (using the frequency ≥ 1 and intensity ≥ 3 rule) in association with CAPS-based LPA determinations of membership in the dissociative subtype versus the high PTSD symptom class yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of .89 (SE = .04, p < .0001, 95% CI for AUC: .81 - .97). Examination of the sensitivity and specificity statistics at various cut-points (Table 4) suggested that the optimal cut-point occurred at endorsement of 2+ symptoms (sensitivity = 77.4%, specificity = 91.1, positive predictive value = 75.0%, negative predictive power = 92.1%). Based on this, we defined DSPS dissociative subtype caseness as endorsement of at least two current Derealization/Depersonalization interview items and compared these determinations to the CAPS-based LPA assignment to the dissociative class versus the high PTSD class. Of those assigned to the dissociative class based on the CAPS LPA, 80.0% met criteria for the dissociative subtype based on endorsement of two or more Derealization/ Depersonalization subscale interview items, whereas 8.9% of the CAPS-based high PTSD class met criteria for the dissociative subtype based on this DSPS cut-score, χ2 (1, n = 120) = 58.18, p <.0001, φ = .696.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and Specificity Values for CAPS-Based Dissociative Subtype Membership as a Function of Endorsement of DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization Items

| Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Predictive Power (+) |

Predictive Power (−) |

Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSPS interview | |||||

| 1 | 83.9 | 75.6 | 54.2 | 93.2 | 77.7 |

| 2 | 77.4 | 91.1 | 75.0 | 92.1 | 87.6 |

| 3 | 54.8 | 96.7 | 85.0 | 86.1 | 86.0 |

| 4 | 32.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 81.1 | 82.6 |

| 5 | 12.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 76.9 | 77.7 |

| 6 | 6.45 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 75.6 | 76.0 |

| 7 | 3.23 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 75.2 |

| DSPS self-report | |||||

| 1 | 100 | 52.5 | 32.1 | 100 | 61.2 |

| 2 | 100 | 67.5 | 40.9 | 100 | 73.5 |

| 3 | 100 | 75 | 47.4 | 100 | 79.6 |

| 4 | 100 | 82.5 | 56.3 | 100 | 85.7 |

| 5 | 66.7 | 87.5 | 54.6 | 92.1 | 83.7 |

| 6 | 22.2 | 90 | 33.3 | 83.7 | 77.6 |

| 7 | 22.2 | 92.5 | 40 | 84.1 | 79.6 |

Note. CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; DSPS = Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale

Generalizability of DSPS Interview to Self-Report

We applied the interview-derived 2+ scoring rule to the self-report DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization subscale and compared this definition of subtype caseness with that from the DSPS interview and CAPS-based LPA determinations. Among the 92 participants who completed both the interview and self-report versions of the DSPS, the McNemar test showed no significant difference between subtype classification across administration modality (p = .219, φ = .82). However, differences emerged in comparing subtype determinations from the self-report DSPS to the CAPS-based LPA classification (p < .001, φ = .57). Based on this, we conducted an ROC on the self-report DSPS Derealization/Depersonalization subscale (as we did on the interview version) to determine cut-points to maximize accuracy of dissociative subtype identification. We found that the presence of four items on the Derealization/Depersonalization self-report subscale was the optimal cut-point (sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 82.5, positive predictive value = 56.25%, negative predictive power = 100%, accuracy = 85.71%; Table 4).

Discussion

Results of this study support the utility of the DSPS to index a clinically significant subtype of PTSD that is marked by comorbid symptoms of derealization and depersonalization. By focusing on the psychometric properties of the current DSPS severity items in a sample of veterans with substantial PTSD symptomatology, the study replicated the three-factor structure of the measure, and delineated the boundaries between the measure and a range of traits including personality and absorption. In particular, the DSPS evidenced good discrimination with an array of personality traits, including negative affect and demoralization, and trait absorption. The study further demonstrated the utility of the measure to identify the dissociative subtype through evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of scale cut-points (in both interview and self-report formats) in comparison to empirical CAPS-based determinations of the subtype.

The results of multiple regression analyses suggested differential patterns of association between MMPI-2-RF scales and the dissociative subtype of PTSD in comparison to the high PTSD symptom group without dissociation. RC2 (Low Positive Emotions) and RC8 (Aberrant Experiences) emerged as significant predictors of the dissociative subtype while RCd (Demoralization) evidenced greater specificity for high PTSD symptoms without dissociation. These findings highlight the importance of identifying more homogenous subtypes of posttraumatic reactions in order to identify specific correlates of each posttraumatic presentation.

As well, results help characterize the nature of the dissociative subtype itself and shed light on the temperament underlying dissociative phenomena. There are two prominent models of dissociation in relation to PTSD: the first holds that dissociation is a form of conscious or conditioned trauma-related avoidance, which involves the down-regulation of highly arousing emotion (Lanius et al., 2012; see also Dutra & Wolf, 2017 for a review). The second theory suggests that biological differences in integrating sensory and cognitive processes might predispose to dissociation, especially in the context of trauma or other stressors (Giesbrecht et al., 2008; Lynn et al., 2014). While our data could not directly address the latter hypothesis, these results do have bearing on the former: if dissociation were fundamentally related to a tendency towards a high level of negative arousal that is subsequently down-regulated, we might expect to see associations between RC7 (Dysfunctional Negative Emotions) and the subtype. We did not find evidence of this, rather, the data supported an association between RC2 and the dissociative subtype, suggesting that those who dissociate are lacking in positive emotional experiences and social connection. This suggests an alternate, orthogonal conceptualization of PTSD-associated dissociation: Given the stability of temperament over time, these results raise the possibility that a biological predisposition towards low positive affect (as opposed to suppression of high negative affect) may be a risk factor for dissociation. Longitudinal study is necessary to test this.

The scales that showed some specificity for dissociative symptomology in this study (THD, RC2, and RC8) have also been associated with poor treatment response. Elevations on THD and RC8 have been associated with treatment dropout (Mattson, Powers, Halfaker, Akeson, & Ben-Porath, 2012) and elevations on RCd, RC2, and RC8 have been linked to less reduction in psychiatric symptoms following treatment (Scholte et al., 2012). This is consistent with data suggesting that the subtype may interfere with PTSD treatment response (Wolf et al., 2016).

Notably, the Psychogenic Amnesia subscale was not strongly related to any of the external correlates evaluated in this study, including PTSD. This is consistent with evidence that this symptom tends to load poorly in factor analytic examinations of PTSD (e.g., Weathers et al., 2018). Future studies may benefit from over-sampling individuals with this symptom to ensure adequate variability for analytic purposes and from including a greater range of potentially related variables (e.g., those indexing self-reported memory) to better determine the correlates of this criterion. Additional evaluation of these DSPS items is warranted.

Findings also suggested that exposure to MST was associated with greater likelihood of dissociative subtype assignment, suggesting a possible etiological role for MST. This interpretation was complicated by the finding that women were also more likely to be assigned to the dissociative subtype and to report MST. Thus, it is difficult to disentangle effects related to MST, sex, and their combination. We have previously found that exposure to sexual trauma across the lifetime was associated with the dissociative subtype (Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012), but not all studies have reported this association (Armour, Karstoft, et al., 2014; Hansen, Ross, & Armour, 2017), suggesting the need for additional research in large samples with sufficient variability and power to examine the independent effects of trauma type from sex.

Given the brief nature of the DSPS and its flexible administration format, the measure could prove broadly useful in clinical and research settings in which the goal is to distinguish the subtype without substantial participant or clinician burden. In fact, the sensitivity and specificity statistics at the recommended cut-points on the current Derealization/Depersonalization subscale indicate strong predictive value of the DSPS in determining dissociative subtype caseness, as compared to a structured diagnostic interview-based determination. While we recommend the two-item Derealization/Depersonalization subscale threshold for the interview DSPS administration, we recommend four items as the cut-point on the self-report version. The lower threshold for dissociative subtype caseness on the interview administration is likely related to the ability of clinicians to exclude symptoms more relevant to other diagnoses and to clarify symptom presentation. For example, interviewers can clarify the context of dissociative experiences and address outstanding confusion. This is crucial for disentangling genuine dissociative symptomatology from more benign, idiosyncratic responses to the items. The interview format also allows the administrator to confirm that reported instances of dissociation were not isolated to situations in which the respondent used mind-altering or sleep-inducing substances, or experienced extreme fatigue, temporal lobe epilepsy, or traumatic brain injury. The cognitive symptoms associated with these states and conditions could simulate dissociative symptoms (Giesbrecht et al., 2008; Giesbrecht, Merckelbach, Geraerts, & Smeets, 2004), and thus it is critical that interviewers rule out their potential contribution to dissociative presentations. Cut-point recommendations for the self-report DSPS are based on a subset of the data, and thus additional research in larger samples is needed to confirm this recommendation.

Study limitations include the use of a hybrid measure of PTSD symptoms that was originally developed as self-report but administered here in interview format, and the lack of secondary ratings on the PCL/NSES interview, prohibiting evaluation of inter-rater reliability. Alpha coefficient for the hyperarousal symptom cluster was lower than typically reported and we suspect this is a function of the meaure’s branching structure, in which these items were only assessed in individuals endorsing current symptoms; we suspect this approach may actually be more accurate than the standard one in which respondents may rate a symptom generally, despite instructions to focus on past month specifically. An additional limitation is the lack of assessment of other psychiatric conditions which could covary with PTSD and dissociative symptoms. In particular, we did not assess attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance-use disorders, psychotic disorders, core dissociative disorders, or mood and anxiety disorders and thus it is unknown if the DSPS can differentiate the dissociative subtype of PTSD from these other conditions and symptoms. We also isolated the MPQ-BF Absorption items from the rest of the MPQ-BF and it is unclear what impact this might have on scale reliability and validity. It is also not clear how administration of the two CAPS dissociative items out of context from the full CAPS may have affected patterns of endorsement and its reliability and validity. The order of administration of the self-report and interview versions of the DSPS was not counterbalanced or standardized, and it is possible this could introduce bias.

While we evaluated the correlation across the interview and self-report measures and examined cut-points across both administration formats, most analyses were conducted on the interview-based DSPS and it is unclear how these results generalize to other contexts that rely heavily on the self-report version. We did not have a sufficient sample to comprehensively evaluate the self-report version of the DSPS. In addition, though all participants in the study screened positive for PTSD on the telephone, not all met criteria for probable diagnosis upon study interview, thus replication of the psychometric qualities of the DSPS among those who meet PTSD diagnostic criteria using structured diagnostic interviews is needed. That said, prior investigations (Wolf, Miller, et al., 2012) have demonstrated an identical dissociative subtype structure when comparing the construct in those with substantial posttraumatic psychiatric symptoms versus those who fully meet the diagnostic threshold for PTSD. Finally, we conducted many different types of analyses which raises the risk of chance findings.

In conclusion, the DSPS showed remarkably reliable patterns of association across our prior epidemiological and this clinical sample of veterans, and across our prior evaluation of the dichotomous lifetime items and this examination of the current symptom severity items. Results highlight the importance of assessing this uncommon but salient presentation of posttraumatic psychopathology and the ease and utility of the DSPS for this purpose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was supported by an award from the University of Minnesota Press, Test Division, and by a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) administered by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research and Development (PECASE 2013A), both to Erika J. Wolf.

Footnotes

The scale is freely available at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/dissociative_subtype_dsps.asp

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Arbisi PA, Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, & Reddy MK (2011). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form in National Guard soldiers screening positive for posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. Psychological Assessment, 23(1), 203–214. 10.1037/a0021339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Elklit A, Lauterbach D, & Elhai JD (2014). The DSM-5 dissociative-PTSD subtype: Can levels of depression, anxiety, hostility, and sleeping difficulties differentiate between dissociative-PTSD and PTSD in rape and sexual assault victims? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(4), 418–426. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Karstoft KI, & Richardson JD (2014). The co-occurrence of PTSD and dissociation: Differentiating severe PTSD from dissociative-PTSD. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(8), 1297–1306. 10.1007/s00127-014-0819-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Műllerová J, & Elhai JD (2016). A systematic literature review of PTSD’s latent structure in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV to DSM-5. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 60–74. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DC, Modrowski CA, Kerig PK, & Chaplo SD (2015). Investigating the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder in a sample of traumatized detained youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(5), 465–472. 10.1037/tra0000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath YS, & Tellegen A (2008). MMPI-2-RF (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form) Manual for administration, scoring and interpretation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, & Witte TK (2014). Dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(4), 388–396. 10.1002/jts.21933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MS, Feeny NC, Connell AM, & Zoellner LA (2018). Exploring evidence of a dissociative subtype in PTSD: Baseline symptom structure, etiology, and treatment efficacy for those who dissociate. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(5), 439–451. 10.1037/ccp0000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, & Lu Lassell F (2012). An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 709–717. 10.1002/da.21920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra SJ, & Wolf EJ (2017). Perspectives on the conceptualization of the dissociative subtype of PTSD and implications for treatment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 35–39. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Brown MF, Steuwe C, & Lanius RA (2015). Latent profile analysis and principal axis factoring of the DSM-5 dissociative subtype. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 26406–26416. 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, & Lanius RA (2006). Toward a psychobiology of posttraumatic self-dysregulation: Reexperiencing, hyperarousal, dissociation, and emotional numbing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 110–124. 10.1196/annals.1364.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht T, Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, & Merckelbach H (2008). Cognitive processes in dissociation: An analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychological Bulletin, 134(5), 617–647. 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H, Geraerts E, & Smeets E (2004). Dissociation in undergraduate students: Disruptions in executive functioning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(8), 567–569. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135572.45899.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen JØ, Stenmark H, Neuner F, & Nordahl HM (2014). Does dissociation moderate treatment outcomes of narrative exposure therapy for PTSD? A secondary analysis from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 21–28. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Műllerová J, Elklit A, & Armour C (2016). Can the dissociative PTSD subtype be identified across two distinct trauma samples meeting caseness for PTSD? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(8), 1159–1169. 10.1007/s00127-016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Ross J, & Armour C (2017). Evidence of the dissociative PTSD subtype: A systematic literature review of latent class and profile analytic studies of PTSD. Journal of Affective Disorder, 213, 59–69. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Baber B, Guille C, & Gros K (2011). The National Stressful Events Web Survey (NSES-W). Charleston, SC: Medical University of South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Bluhm R, Lanius U, & Pain C (2006). A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: Heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(8), 709–729. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Brand B, Vermetten E, Frewen PA, & Spiegel D (2012). The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: Rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 701–708. 10.1002/da.21889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, Brand B, Schmahl C, Bremner JD, & Spiegel D (2010). Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 640–647. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Williamson PC, Boksman K, Densmore M, Gupta M, Neufeld RW, … Menon RS (2002). Brain activation during script-driven imagery induced dissociative responses in PTSD: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Biological Psychiatry, 52(4), 305–311. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01367-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H, Giesbrecht T, McNally RJ, Loftus EF, … Malaktaris A (2014). The trauma model of dissociation: Inconvenient truths and stubborn fictions. Comment on Dalenberg et al. (2012). Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 896–910. 10.1037/a0035570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion BE, Sellbom M, & Bagby RM (2011). The detection of feigned psychiatric disorders using the MMPI-2-RF overreporting validity scales: An analog investigation. Psychological Injury and Law, 4(1), 1–12. 10.1007/s12207-011-9097-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson C, Powers B, Halfaker D, Akeson S, & Ben-Porath Y (2012). Predicting drug court treatment completion using the MMPI-2-RF. Psychological Assessment, 24(4), 937–943. 10.1037/a0028267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Kilpatrick D, Resnick H, Marx BP, Holowka DW, … Friedman MJ (2013). The prevalence and latent structure of proposed DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. national and veteran samples. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(6), 501–512. 10.1037/a0029730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Reardon A, Greene A, Ofrat S, & McInerney S (2012). Personality and the latent structure of PTSD comorbidity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(5), 599–607. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Műllerová J, Hansen M, Contractor AA, Elhai JD, & Armour C (2016). Dissociative features in posttraumatic stress disorder: A latent profile analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 601–608. 10.1037/tra0000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, & Tellegen A (2002). Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 14(2), 150–163. 10.1002/da.21938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Suvak MK, Johnides BD, Mitchell KS, & Iverson KM (2012). The impact of dissociation on PTSD treatment with cognitive processing therapy. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 718–730. 10.1002/da.21938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Baník G, Dědová M, Mikulášková G, & Armour C (2018). Assessing the structure and meaningfulness of the dissociative subtype of PTSD. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(1), 87–97. 10.1007/s00127-017-1445-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte W, Tiemens B, Verheul R, Meerman A, Egger J, & Hutschemaekers G (2012). The RC scales predict psychotherapy outcomes: The predictive validity of the MMPI-2’s restructured clinical scales for psychotherapeutic outcomes. Personality and Mental Health, 6(4), 292–302. 10.1002/pmh.1190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellbom M, & Bagby RM (2010). Detection of overreported psychopathology with the MMPI-2-RF [corrected] validity scales. Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 757–767. 10.1037/a0020825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel D, & Cardeña E (1991). Disintegrated experience: The dissociative disorders revisited. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 366–378. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuwe C, Lanius RA, & Frewen PA (2012). Evidence for a dissociative subtype of PTSD by latent profile and confirmatory factor analyses in a civilian sample. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 689–700. 10.1002/da.21944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, & Ben-Porath YS (2008). MMPI-2-RF: Technical manual. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Ben-Porath YS, McNulty JL, Arbisi PA, Graham JR, & Kaemmer B (2003). The MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales: Development, validation, and interpretation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, & Waller NG (2008). Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire In Boyle GJ, Matthews G & Saklofske DH (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment, Vol 2: Personality measurement and testing (pp. 261–292). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). Interview available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, … Marx BP (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. 10.1037/pas0000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr P (2014). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at http://www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, & Keane TM (1999). Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment, 11(2), 124–133. 10.1037/1040-3590.11.2.124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Lunney CA, Miller MW, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, & Schnurr PP (2012). The dissociative subtype of PTSD: A replication and extension. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 679–688. 10.1002/da.21946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Lunney CA, & Schnurr PP (2016). The influence of the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder on treatment efficacy in female veterans and active duty service members. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(1), 95–100. 10.1037/ccp0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Reardon AF, Ryabchenko KA, Castillo D, & Freund R (2012). A latent class analysis of dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for a dissociative subtype. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(7), 698–705. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Mitchell KS, Sadeh N, Hein C, Fuhrman I, Pietrzak RH, & Miller MW (2017). The Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Scale: Initial evaluation in a national sample of trauma-exposed veterans. Assessment, 24(4), 503–516. 10.1177/1073191115615212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Rasmusson AM, Mitchell KS, Logue MW, Baldwin CT, & Miller MW (2014). A genome-wide association study of clinical symptoms of dissociation in a trauma-exposed sample. Depression and Anxiety, 31(4), 352–360. 10.1002/da.22260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.