Abstract

Objectives

People face decisions about how to sequence payments and events, including when to schedule bigger events relative to smaller ones. We examine age differences in these sequence preferences.

Methods

We gave a national adult life-span sample (n = 1,296, mean = 53.06 years, standard deviation = 16.33) four scenarios describing a positive or negative hedonic (enjoyable weekends, painful dental procedures) or monetary (receiving versus paying money) event. We considered associations among age, sequence preferences, three self-reported decision-making processes—emphasizing experience, emotion, and reasoning—and two dimensions of future time perspective—focusing on future opportunities and limited time.

Results

Older age was associated with taking the “biggest” event sooner instead of later, especially for receiving money, but also for the other three scenarios. Older age was associated with greater reported use of reason and experience and lesser reported use of emotion. These decision-making processes played a role in understanding age differences in sequence preferences, but future time perspective did not.

Discussion

We discuss “taking the biggest first” preferences in light of prior mixed findings on age differences in sequence preferences. We highlight the distinct roles of experience- and emotion-based decision-making processes. We propose applications to financial and health-care settings.

Keywords: Decision making, Event sequences, Experience, Emotion, Future time perspective

People commonly face choices about scheduling positive events such as how to spend their free time, and negative events such as painful medical procedures. They also face choices about sequences for receiving money and paying off loans. Such choices often involve when to schedule bigger events relative to smaller ones. For example, should a larger or smaller loan be paid off first? Most decision research, including that on sequence preferences, is conducted with college students (Peters & Bruine de Bruin, 2012; Strough, Karns, & Schlosnagle, 2011). Yet, understanding age differences in sequence preferences could inform the design of programs and services that aim to help people of all ages to improve their wealth, health, and psychological well-being. We therefore investigated associations among age and sequence preferences in positive and negative hedonic and monetary contexts. Using our conceptual framework (Strough, Parker, & Bruine de Bruin, 2015), we focused on experience-, emotion-, and reasoning-based decision-making processes, as well as future time perspective, to understand age differences in sequence preferences.

Preferences for Improving Sequences

Monetary Events

Choices about sequences of monetary events often suggested a preference for improving sequences where the best event is “saved for last” (Loewenstein & Prelec, 1993). For example, for positive monetary events such as receiving income, people preferred increasing instead of decreasing increments (Duffy & Smith, 2013; Loewenstein & Sicherman 1991). This preference conflicts with the normative economic principle of maximizing the present value of funds (Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991).

When asked about negative events such as paying money, people also preferred improving sequences in which payments reduced with time, even overpaying initially if this resulted in a refund later (Prelec & Loewenstein, 1998). A real-world example of such preferences is seen in U.S. taxpayers’ over-withholding of income to produce refunds (Gandhi & Kuehlwein, 2016). However, preferences for improving monetary sequences were not persistent. When making choices about a monetary windfall, people preferred to receive a larger amount of money up front, even when this led to less money overall (Read & Powell, 2002).

Hedonic Events

Preferences for improving sequences have been found for positive hedonic events, such as dining out, where students saved the best meal for last (Loewenstein & Prelec, 1993). For negative events, students preferred to get the worst experience over with first, ending with the least painful one (Chapman, 2000). When sequencing a mixture of positive, negative, and neutral experiences, students preferred positive experiences to be last (Lau-Gesk, 2005). Such preferences have been attributed to anticipatory emotions experienced while waiting for events to happen (Loewenstein, 1987). By putting off a positive event, good feelings can be prolonged through savoring, whereas getting a negative event over with prevents anticipatory dread (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001).

Age and Sequence Preferences

Of the four studies examining age differences in sequence preferences, two investigated mixed-affect sequences and yielded contradictory results. When choosing the viewing order of negative, neutral, and positive images, older adults were less likely than younger adults to construct improving sequences and put positive images relatively earlier (Löckenhoff, Reed, & Maresca, 2012). However, older age was associated with stronger preferences for improving sequences of hypothetical foods that, respectively, tasted terrible, mediocre, and excellent (Drolet, Lau-Gesk, & Scott, 2011). It is unclear whether event magnitude contributed to age differences because the magnitude of negative and positive events was equated (Löckenhoff et al., 2012) or confounded with valence (Drolet et al., 2011).

When presented with hypothetical scenarios about receiving income, older age was associated with more normatively correct preferences, to receive larger amounts sooner instead of later (Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991). However, another study found no age differences in actual experiences of winning or losing money, or of electrodermal shocks (Löckenhoff, Rutt, Samanez-Larkin, O’Donoghue, & Reyna, 2017). No studies have contrasted age differences in preferences for sequences of solely positive or solely negative events. Yet, doing so would disentangle event magnitude from valence. As we discuss next, older age could be associated with preferring to take the biggest event first, irrespective of valence.

Decision-Making Processes, Age, and Sequence Preferences

Experience

Life experience increases with age (Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006). Theorists have therefore posited that older adults rely more on experience when making decisions (Peters, Hess, Västjfäll, & Auman, 2007; Strough et al., 2015). One of the few tests of this idea found that crystallized intelligence, presented as a proxy for experience, helped older people to compensate for declines in fluid cognitive abilities when making financial decisions (Li et al., 2014).

With increased experience, cognitively effortful analytic processes may become automatic, giving rise to intuition based on learned associations (Pretz et al., 2014). Age differences in this type of experience have not been examined but could be important for decision making (Strough, Karns, et al., 2011). For example, older adults’ greater financial experience may facilitate understanding the present value of money, such that older age is associated with preferring to receive larger (vs smaller) amounts of money sooner (Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991). Older adults’ financial experience could also contribute to preferences for paying off larger loans sooner than smaller loans, thereby avoiding accrual of interest when the interest rates on the loans is the same. Thus, greater reliance on experience might be associated with preferring to both pay and receive larger amounts sooner than smaller amounts. For hedonic events, life experience with the affective benefits of avoiding dread could be associated with preferring to get negative experiences over with, or stronger preferences for improving hedonic sequences, in older age (Drolet et al., 2011).

Emotion

Traditionally, dual-process models have combined experience and emotion when describing decision-making processes (Evans, 2008). They distinguish an “affective/experiential” system that is guided by emotions and experience, and is faster and less effortful than a “deliberative” system (Kahneman, 2003). However, elsewhere we have argued that conceptualizing experience and emotion as distinct but overlapping processes could advance research on aging and decision making (Strough et al., 2011, 2015). For example, basing decisions on incidental emotions may be disadvantageous, but affective associations learned through experience may be advantageous (Peters et al., 2007).

Recently, measures have been developed to distinguish emotion-based processes from experience-based processes (Pretz et al., 2014), but they have not yet been used in age-diverse samples. If some automatic decisions are based on emotions, and others on experience, then each process could show different associations with age, and with sequence preferences. For example, experience-based processing might facilitate normatively correct economic preferences, as discussed. In contrast, if emotion-based processing is a source of decision errors (Kahneman, 2003), then relying on emotions might be associated with non-normative economic preferences. Further, if older adults are less likely to rely on emotions when making decisions (Delaney, Strough, Parker, & Bruine de Bruin, 2015), this could explain their normatively correct economic preferences (Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991). Using Pretz and colleagues’ (2014) measures in the current study allowed us to distinguish age-related differences that may exist between these two processing modes.

Reason

Theorists posit that due to age-related fluid cognitive declines (Salthouse, 2004) deliberative processing decreases with age (Peters et al., 2007). Older people experience cognitive effort as physiologically more costly and become more selective about using their cognitive resources (Hess, 2014). Few studies have investigated age differences in reported use of decision styles, but Delaney and colleagues (2015) found that older age was associated with greater self-reported use of deliberate decision processes (cf., Bruine de Bruin, Parker, & Strough, 2016). Self-reports of using reason to make decisions have been linked to better performance on decision-making tasks (Bruine de Bruin, Parker, & Fischhoff, 2007), but links with sequence preferences have not been examined.

Future Time Perspective, Age, and Sequence Preferences

Socioemotional selectivity theory posits that older age is associated with prioritizing positive experiences in the “here and now” due to viewing time as limited (Carstensen, 2006). Limited future time perspective has been associated with less willingness to delay positive experiences (Löckenhoff et al., 2012), suggesting that perceiving limited time might be associated with preferences for taking “bigger” positive events sooner than less positive ones. Perceiving a limited future also could be associated with delaying the worst event in a negative sequence due to the possibility of never having to experience it at all. Alternatively, it could be associated with preferring to get the worst over with to avoid anticipatory dread that could interfere with feeling good in the present.

The Present Research

In summary, we built from the literature to conduct an exploratory study of age differences in sequence preferences. To avoid confounds of event magnitude and valence, we compared sequences that were solely positive to those that were solely negative. If older age was associated with taking the biggest hedonic event first, this could reconcile seemingly conflicting findings about age differences in preferences for improving sequences. For the monetary context, we investigated whether the association between older age and more normatively correct preferences for receiving money (Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991), generalized to paying money.

We also for the first time explored age differences in the roles of experience, emotion, and reason in sequence preferences. Building from theory (Strough et al., 2011, 2015), we investigated whether decision-making processes based on experience versus emotion had different associations with age and sequence preferences. We investigated whether associations found in prior research among age, future time perspective, and sequence preferences (Löckenhoff et al., 2012) generalized to our scenarios. This approach was reflected in three research questions:

1. Is age associated with sequence preferences in positive and negative hedonic and monetary contexts?

2. Are self-reported use of experience, emotion, and reason to make decisions associated with age and sequence preferences?

3. Is future time perspective associated with age and sequence preferences?

Method

Participants

Participants were from RAND’s American Life Panel, a probability-sampled internet-based panel study designed to represent U.S. adults age 18 and older (see https://mmicdata.rand.org/alp/). The study was approved by RAND’s Human Subjects Protection Committee. Each participant was invited to participate in the first of two surveys. Those who completed the first were invited to complete the second. The surveys’ procedure is described below. Of the 1, 996 panelists invited to the first survey, 1, 483 (74.3%) responded. Of these, 1, 328 (89.5%) responded to the second survey. Of these, 1, 296 (97.7%) answered all four sequence preference questions. (Data were missing for 14 [monetary, positive], 10 [monetary, negative], 18 [hedonic, positive], and 13 [hedonic, negative] cases. Surveys (390 and 391) are available at: https://alpdata.rand.org/?page=data.) Age, gender, race, education, and income did not differ significantly between those who answered all four questions and those who did not (all p > .05).

The final sample (n = 1, 296) included adults aged 20–91 years (mean [M] = 53.06, standard deviation = 16.33, ), 58.8% women, 81.3% Whites/Caucasians, and 84.3% non-Hispanics/Latinos. Fifty-four percent had an associate’s degree or higher, 51% reported their family income as $49, 999 or less.

Procedure

Participants completed one positively valenced and one negatively valenced survey, in counterbalanced order, a few weeks apart. Each began with: “This survey will ask you to make decisions about things that will happen now or in the future. There are no right or wrong answers to these questions. We are merely interested in what you think.” Each survey presented a monetary context followed by a hedonic context. This design allowed a within-subjects comparison of valence for each context, without repeating positive and negative events in the same survey. Table 1 summarizes the four decision scenarios used to elicit preferences for sequences of receiving an inheritance (positive money), paying bills (negative hedonic), spending a month of enjoyable weekends (positive hedonic), and a month of weekly painful dental procedures (negative hedonic). Participants also took part in an experiment on thinking styles that did not interact with any of our independent variables and had no effect on our dependent measures, p > .05.

Table 1.

Within-Subject Decision Scenarios

| Valence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Context | Positive | Negative |

| Hedonic events | Enjoyable weekends: Imagine that you are deciding how you will spend your time over the next four weekends. Some weekends will be very enjoyable, and others will not be enjoyable at all. There are different ways the weekends could be scheduled over the next month. One way would be for the early weekends to be very enjoyable and the later weekends to be not enjoyable at all. Another way would be for the early weekends to be not enjoyable at all and the later weekends to be very enjoyable. In all cases, the total amount of enjoyment for the month is the same. How would you prefer to spend your time? | Painful procedures: Imagine that for the next four weeks you will need to visit the dentist once each week. Sometimes the procedures will be very painful, and other times they will be not painful at all. There are different ways the procedures could be scheduled over the next month. One way would be for the early procedures to be very painful and the later procedures to be not painful at all. Another way would be for the early procedures to be not painful at all and the later procedures to be the very painful. In all cases, the total amount of pain for the month is the same, and at the end of the month you will be pain free. How would you prefer to visit the dentist? |

| Monetary events | Receiving money. Imagine you just found out that that you will receive a very large monetary inheritance from a relative that you didn’t even know you had. You will be given the money in multiple installments over time. There are different ways that you can receive the money. One way would be to receive larger amounts of money early and smaller amounts of money later. Another way would be to receive smaller amounts of money early and larger amounts of money later. In all cases, the total amount of money would be the same. How would you prefer to receive the money? | Paying money. Imagine that you owe a very large amount of money. You will have to pay out the money in multiple installments over time. There are different ways that you could make the payments. One way would be to pay larger amounts of money early and to pay smaller amounts of money later. Another way would be to pay smaller amounts of money early and to pay larger amounts of money later. In all cases, the total amount of money would be the same. How would you prefer to pay the money? |

The positively valenced survey ended with the inferential and affective subscales of the Types of Intuition scale (Pretz et al., 2014) and the rational subscale of Scott and Bruce’s (1995) decision styles inventory. The negatively valenced survey ended with a 12-item version of Carstensen and Lang’s (1996) future time perspective scale (Strough, Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Lemaster, et al., 2016). When at least 75% of scale items were complete, their mean was used to estimate the missing data and compute a scale score, yielding about 20 more usable cases. The significance of results was unaffected by whether missing data were excluded versus included. Gender, education, and income did not differ between responders and nonresponders, p > .05. For the Types of Intuition, Rational, and Future Time Perspective scales, responders [vs nonresponders] were more likely to be older and white, p < .001.

Measures

Hedonic Sequences

Participants indicated their preferences for sequences of hedonic events on a 1–6 scale. For the month of enjoyable weekends scenario (positive valence), 1 was labeled “Start with most enjoyable weekends first, end with least enjoyable” and 6 was labeled “Start with least enjoyable weekends first, end with most enjoyable.” For the month of painful procedures scenario (negative valence), 1 was labeled “Start month with most painful procedures first, end with least painful” and 6 was labeled “Start month with least painful procedures first, end with most painful.” Lower ratings indicated a preference for taking the “biggest” event sooner over later (starting off with the most pleasant weekend, or with the most painful procedure). Preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events and higher scores for positive events.

Monetary Sequences

The response scale for sequences of receiving (positive valence) and paying (negative valence) money ranged from 1, labeled “Start with larger amounts first, end with the smaller, ” to 6, labeled “Start with smaller amounts first, end with the larger.” For both items, lower ratings indicated a preference for the largest monetary installment sooner over later. Normatively correct preferences of maximizing current value were reflected in lower scores for receiving money and higher scores for paying money. Preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events and higher scores for positive events.

Experience

An 8-item Types of Intuition subscale (TIntS; Pretz et al., 2014) assessed using experience to make decisions. For example, “When I make a quick decision in my area of expertise, I can justify the decision logically.” Response options ranged from 1=“definitely false” to 5=“definitely true” (α = .75).

Emotion

Another 8-item TIntS subscale (Pretz et al., 2014) assessed using emotion to make decisions. For example, “I tend to use my heart as a guide for my actions.” Response options ranged from 1=“definitely false” to 5=“definitely true” (α = .71).

Reason

The 4-item rational decision-making style measure (Scott & Bruce, 1995) assessed using reason to make decisions, for example, “I make decisions in a logical and systematic way.” Response options ranged from 1=“completely disagree” to 5=“completely agree” (α = .87).

Future Time Perspective

A 12-item version of Carstensen and Lang’s (1996)future time perspective scale assessed future time perspective (Strough, Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Lemaster, et al., 2016). Seven items assessed focus on future opportunities, “My future is filled with possibilities” (α = .91), five assessed focus on limited time, “I have limited time left to live my life” (α = .77). Response options ranged from 1=“very untrue” to 7=“very true.” The subscales were correlated at −.45 (p < .001).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

An analysis of variance indicated no significant main effects or interactions with survey order, p >.05. Subsequent analyses collapsed across order. Income and education were correlated with some study variables (Supplementary Table 1) and were controlled in all analyses. Except when noted, analyses were unaffected by the inclusion of these controls.

1. Is Age Associated With Sequence Preferences in Positive and Negative Hedonic and Monetary Contexts?

We estimated separate general linear models in SPSS for each context to examine effects of the within-subjects variable, valence (positive, negative), and the between-subjects continuous variable, age. We report significant associations.

Hedonic Contexts

For hedonic contexts, the effect of valence, F(1, 1290) = 97.99, p < .0001, η2 = .07 indicated preferences for improving sequences by delaying positive events (M = 4.49, SE = .05) relative to hastening negative ones (M = 1.88, SE = .04).

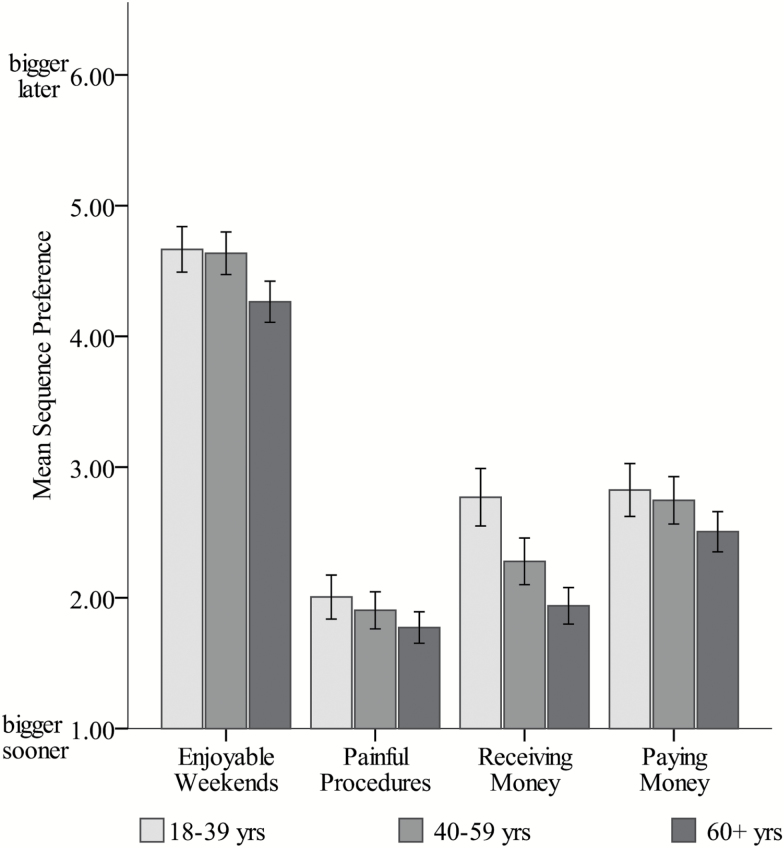

For positive events of enjoyable weekends (r = −.11, p < .001) and negative events of painful dental procedures (r = −.07, p < .008), older age was associated with preferring bigger events sooner instead of later, F(1, 1290) = 25.03, p < .0001, η2 = .02 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age differences in sequence preferences in positive and negative hedonic and monetary contexts. Hedonic contexts were enjoyable weekends (positive) and painful procedures (negative). Monetary contexts were receiving money (positive) and paying money (negative). Age is depicted as a categorical variable in the figure, but was a continuous variable in all analyses. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the mean. For all four items, lower ratings indicated a preference for the “biggest” event sooner over later meaning that preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events (painful procedures, paying money) and higher scores for positive events (enjoyable weekends, receiving money). Normatively correct preferences of maximizing current value were shown in lower scores for receiving money and higher scores for paying money.

Monetary Contexts

For the monetary contexts, the effect of valence, F(1, 1290) = 11.27, p = .001, η2 = .01, indicated preferences for receiving larger amounts of money sooner (M = 2.26, SE = .05) relative to delaying payments (M = 2.66, SE = .05).

The significant association between age and sequence preferences, F(1, 1290) = 47.52, p < .0001, η2 = .04, was modified by an interaction with valence, F(1, 1290) = 13.81, p < .0001, η2 = .01. Older age was significantly associated with preferring to receive (r = −.21, p < .001) and pay (r = −.06, p < .05) bigger (vs smaller) amounts sooner (Figure 1). The association was significantly stronger for choices about receiving versus paying money, p <.01. Older age was associated with normatively correct preferences when receiving money, but was not associated with normatively correct preferences when paying it.

2. Are Self-Reported Use of Experience, Emotion, and Reason to Make Decisions Associated With Age and Sequence Preferences?

Older age was significantly correlated with greater reported use of experience and reason, and less use of emotion (Table 2). Thus, automatic decisions based on experience versus emotion were differently correlated with age.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | −.11** | −.08** | −.21** | −.06* | .07* | −.14** | .07* | −.43*** | .29** | |

| 2. Hedonic-positive: enjoyable weekends | −.11** | .14** | −.02 | .10** | −.05 | .01 | .06* | −.03 | ||

| 3. Hedonic-negative: painful procedures | .06* | .19** | −.11** | .08** | −.08** | .02 | −.04 | |||

| 4. Money-positive: receiving money | .01 | −.07* | .10** | .01 | .11** | −.12** | ||||

| 5. Money-negative: paying money | −.08** | .01 | −.09** | .01 | .01 | |||||

| 6. Experience | .04 | .26** | .09** | −.01 | ||||||

| 7. Emotion | −.19** | .13** | −.10** | |||||||

| 8. Reason | .17** | −.02 | ||||||||

| 9. Future opportunities | −.45*** | |||||||||

| 10. Limited time | ||||||||||

Note. For age, higher values indicated older age. For hedonic and monetary contexts, lower ratings indicated a preference for the “biggest” event sooner over later meaning that preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events (painful procedures, paying money) and higher scores for positive events (enjoyable weekends, receiving money). Normatively correct preferences of maximizing current value were shown in lower scores for receiving money and higher scores paying money. Greater reported reliance on experience, emotion, and reason to make decisions were indicated by higher values. Greater focus on future opportunities and limited time were indicated by higher values.

N =1,289

p <.05

p < .01

p <.001.

Greater use of experience was correlated with preferences for “bigger” events sooner than smaller ones for three scenarios: painful procedures, paying, and receiving money. For the other scenario (enjoyable weekends), experience was correlated with delaying the more enjoyable (bigger) weekend relative to less enjoyable ones. Thus, greater use of experience was significantly correlated with preferences for improving sequences, except when receiving money. (When education and income were not controlled, the association between experience and preferring larger payments sooner was marginal [p = .06].)

Greater use of emotion was correlated with preferring bigger events later than smaller events for painful procedures and receiving money. Thus, greater use of emotion was correlated with preferences for increasing pain and receiving larger amounts of money later—with the latter reflecting a nonoptimal choice according to normative economic theory.

Greater use of reason was correlated with preferences for bigger events sooner for painful procedures and paying money. Thus, use of reason was correlated with preferences for improving sequences of negative events. For money, this was a nonoptimal choice according to normative economic theory.

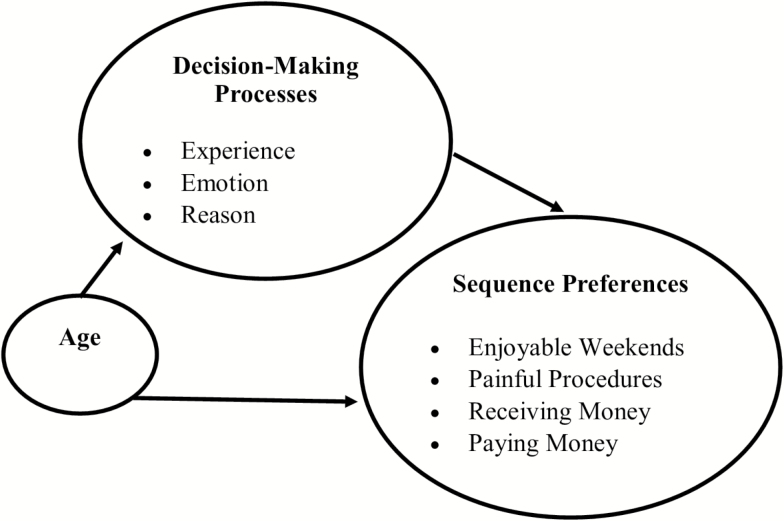

To examine whether decision-making processes mediated age differences in sequence preferences, we used Hayes' (2013) PROCESS macro with 5, 000 bootstrapped resamples (Figure 2). As recommended (Hayes, 2013), we report unstandardized effects. Age was entered as a continuous variable.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of decision-making processes as mediators of age differences in sequence preferences in positive and negative hedonic and monetary contexts. Hedonic contexts were enjoyable weekends (positive) and painful procedures (negative). Monetary contexts were receiving money (positive) and paying money (negative).

First, age was significantly associated with all three decision-making processes (Table 3). Second, after controlling for the other decision-making processes and age (a) greater use of experience was significantly associated with preferences for improving sequences, except when receiving money, (b) greater use of emotion was significantly associated with preferring to receive larger amounts of money later, and (c) greater use of reason was significantly associated with preferring to pay larger amounts of money sooner (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Age and Decision-Making Processes and Between Decision-Making Processes and Sequence Preferences in Positive and Negative Hedonic and Monetary Contexts

| Variable | Decision-Making Process | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | Emotion | Reason | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Age | .002 (.001)* | −.005 (.001)* | .003 (.001)* |

| Hedonic contexts | |||

| Enjoyable weekends | .394 (.109)*** | −.170 (.097)+ | −.053 (.069) |

| Painful procedures | −.289 (.092)* | .145 (.074)+ | −.092 (.059) |

| Monetary contexts | |||

| Receiving money | −.245 (.113)* | .206 (.091)* | .127 (.072) |

| Paying money | −.232 (.116)* | −.008 (.093) | −.192 (.074)* |

Note. Greater reported reliance on experience, emotion, and reason to make decisions were indicated by higher values. For hedonic and monetary contexts, lower ratings indicated a preference for the “biggest” event sooner over later meaning that preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events (painful procedures, paying money) and higher scores for positive events (enjoyable weekends, receiving money). Normatively correct preferences of maximizing current value were shown in lower scores for receiving money and higher scores paying money.

N =1,289, +p = .05

p < .05

p <.001.

Third, for the positive hedonic context of enjoyable weekends, the direct effect of older age on preferences for more enjoyable weekends sooner than less enjoyable ones was stronger after taking into account the significant indirect effect of older adults’ greater reported use of experience, indicating a suppression effect (Table 4). (The indirect path through emotion was significant when education and income were not controlled.)

Table 4.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Age on Sequence Preferences in Positive and Negative Hedonic and Monetary Contexts

| Direct effect of age before and after accounting for indirect effects | Indirect effect of age through decision-making process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Experience | Emotion | Reason | |

| Context and Valence | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) |

| Hedonic contexts | |||||

| Enjoyable weekends | −.013 (.003)*** | −.015 (.003)* | .0007 (.0004)* | .0009 (.0005) | −.0002 (.0003) |

| Painful procedures | −.007 (.003)** | −.005 (.003)* | −.0005 (.0003)* | −.0007 (.0004) | −.0003 (.0002) |

| Monetary contexts | |||||

| Receiving money | −.024 (.003)*** | −.023 (.003)*** | −.0004 (.0003) | −.0010 (.0005)* | .0004 (.0003) |

| Paying money | .007 (.003)* | −.006 (.003)+ | −.0004 (.0003) | .0000 (.0005) | −.0006 (.0004)* |

Note. Indirect effects represent the contribution of each process when holding the others constant and the change in the criterion variable associated with a change of only one year of age. To see the effect of a larger age difference, the estimate can be multiplied by, for example, 20 to show the effect of a 20 year age difference. To facilitate that exercise, we provide estimates of indirect effects to four decimal places. For age, higher values indicated older age. Greater reported reliance on experience, emotion, and reason to make decisions were indicated by higher values. For hedonic and monetary contexts, lower ratings indicated a preference for the “biggest” event sooner over later meaning that preferences for improving sequences were shown in lower scores for negative events (painful procedures, paying money) and higher scores for positive events (enjoyable weekends, receiving money). Normatively correct preferences of maximizing current value were shown in lower scores for receiving money and higher scores paying money.

N = 1,289

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

For the negative hedonic context of painful procedures, the direct effect of older age on preferring more painful procedures sooner than less painful ones was reduced after accounting for the significant indirect effect of older adults’ greater reported use of experience, consistent with mediation (Table 4).

For the positive monetary context of receiving money, the direct effect of older age on preferences for receiving larger amounts of money sooner than smaller amounts was reduced after taking into account the significant indirect effect of older adults’ lesser reported use of emotion, consistent with mediation (Table 4). (The indirect path through experience was significant when education and income were not controlled.)

For the negative monetary context of paying money, the direct effect of older age on preferences for paying larger amounts of money sooner than smaller amounts was reduced after accounting for the significant indirect effect of older adults’ greater reported use of reason, consistent with mediation (Table 4).

3. Is Future Time Perspective Associated With Sequence Preferences and Age?

Older age was correlated with focusing more on a limited future and less on future opportunities (Table 2). Greater focus on future opportunities was correlated with preferences for improving sequences of delaying more enjoyable weekends relative to less enjoyable ones. A greater focus on limited time and lesser focus on future opportunities were each correlated with normatively correct preferences to receive larger amounts of money sooner than smaller amounts. Neither dimension of future time perspective was correlated with negatively valenced sequence preferences.

Dimensions of future time perspective were examined as mediators of age differences in sequence preferences (Supplementary Figure 1). First, age was associated with future time perspective dimensions. Second, after accounting for age, neither dimension was significantly associated with sequence preferences for any of the scenarios. Third, bootstrapped estimates of the indirect effect of age through future time perspective dimensions were nonsignificant for each of the four scenarios. Neither focus on future opportunities, nor limited time, mediated age differences in sequence preferences.

Discussion

Understanding sequence preferences is important because the choices people make about when to receive versus pay money and when to schedule aversive health appointments and positive experiences likely have implications for their wealth and psychological well-being. Our findings show that older adults preferred to take the biggest event first. This association was strongest for positive sequences of receiving money, but also characterized the other three sequences we examined. Self-reported decision-making processes accounted for age-related variance in sequence preferences, but future time perspective did not. Our findings offer insights about why older age was associated with preferring bigger events sooner than later.

Age and Sequence Preferences

By showing that older age was associated with taking the biggest event first, we highlight the importance of considering event magnitude along with valence. This could help reconcile seemingly conflicting findings about whether older adults are more or less likely to prefer improving hedonic sequences of saving the best for last (Drolet et al., 2011; Löckenhoff et al., 2012). The valence of events within a mixed-affect sequence may drive age differences in preferences when magnitude is held constant (e.g., Löckenhoff et al., 2012). Otherwise, event magnitude may drive preferences, as shown in our findings. If big events are more arousing, getting them over with may benefit older adults by reducing arousal that challenges their physiological vulnerabilities (Charles & Luong, 2013). Thus, our findings align with the suggestion that older adults avoid arousal (Isaacowitz & Ossenfort, 2017).

Older adults’ preferences for receiving larger amounts of money “up front” are consistent with research showing that older adults’ decisions are more likely than those of younger adults to conform to normative economic principles (Li et al., 2014; Strough, Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Karns, et al., 2016). Yet, older age was also associated with preferences to pay larger (vs smaller) amounts sooner. Getting big payments over with may have utility for avoiding anticipatory dread (Loewenstein et al., 2001), but it violates economic principles. Optimal economic choices among older adults may be context specific (Roalf, Mitchell, Harbaugh, Janowsky, 2012).

Decision-Making Processes, Age, and Sequence Preferences

Older age was associated with greater reported use of experience and lesser reported use of emotions to make decisions, demonstrating the value of considering these as distinct processes (Strough et al., 2011). Further research is necessary to address whether using experience reflects the quality or amount of experience one has.

For painful procedures, older adults’ greater use of experience helped to explain their preferences for worse events sooner than less aversive ones. This could be an example of taking action before an emotion is experienced to mitigate it (Gross, 2001). Other research showed older age was associated with less rumination about past negative events (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2014; Strough, Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Karns, et al., 2016). Older adults may also seek to avoid anticipatory worrying about future negative events.

Older adults’ lesser use of emotions to make decisions (Delaney et al., 2015) facilitated optimizing present value when choosing how to receive money. We have also suggested elsewhere that age-related improvements in emotion regulation facilitate good decision making (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2014).

Older adults’ nonoptimal economic preferences to pay larger amounts of money sooner than smaller amounts was associated with their greater reported use of reason. Their reasoning may have been that making a big payment first would reduce penalties. Other work suggests that people use their experience to “go beyond” researchers’ scenarios (Strough, Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Karns, et al., 2016) and that such inferences are more prevalent when people use logical reasoning (Wong, Kwong, & Ng, 2008). Older adults may also have reasoned that making a big payment up front would reduce dread about impending payments.

Future Time Perspective, Age, and Sequence Preferences

For positive events, the association between older age and present-oriented preferences of bigger events sooner than smaller events are consistent with ideas from socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 2006). Focus on future opportunities was associated with preferences for improving sequences of saving the best for last, replicating Löckenhoff and colleagues (2012). Focus on limited time was associated with preferring to receive bigger amounts of money sooner than smaller amounts. Yet, future time perspective did not account for the association between age and present-oriented sequence preferences. This is inconsistent with socioemotional selectivity theory’s emphasis on time perspective as an explanatory mechanism. We compared hedonic sequences occurring over a month, and monetary sequences occurring over an unspecified time. Past research investigated preferences within a single laboratory session, hypothetical meal, or over 5 years (Drolet et al., 2011; Löckenhoff et al., 2012, Loewenstein & Sicherman, 1991). Future research should examine the role of time frame. Older age and focusing on limited time are associated with perceiving time as passing more quickly for activities with long-term, but not immediate outcomes (John & Lang, 2015).

Future Directions and Conclusions

Because we used one cross-sectional life-span sample and correlational methods, our data cannot address causal, developmental, or cohort effects (Lindenberger, von Oertzen, Ghisletta, & Hertzog, 2011; Maxwell & Cole, 2007; Schaie, 1983). Our hypothetical scenarios may not have captured the complexity of decisions about receiving retirement earnings, or when to engage in health screenings. However, decisions about hypothetical scenarios do predict real-world decision behaviors and outcomes (Bruine de Bruin, et al., 2007).

We did not assess cognitive functioning. Imagining the future taxes cognitive resources that decline with age (Schacter, Gaesser, & Addis, 2013). Older adults are worse than younger adults at imagining events, especially future ones (Rendell et al., 2012). Additional research is required to rule out the possibility that older adults’ present-oriented preferences reflect insufficient cognitive resources to imagine the future.

Our findings suggest that when designing interventions for older adults it may be important to consider their tendency toward making present-oriented choices. In the United States, older adults often choose to receive Social Security benefits before they are eligible to receive full benefits, even though this means they receive less money overall (Purcell, 2010). This burdens the Social Security system and puts older adults at risk for financial disadvantage, by exiting the workforce when earning potential is often at a peak and because annual Social Security benefits will be lower and checks will be smaller. Early retirement also has disadvantages for health and well-being (Calvo, Sarkisian, & Tamborini, 2013; Vo et al., 2015). Perhaps one strategy to encourage older adults to remain in the workforce might be to emphasize present-oriented positive benefits of continuing to work.

Our findings also have potential applications in health-care settings where patients may prefer to get aversive procedures over with sooner rather than later. If this is impossible, then addressing the anxiety this may cause through education and stress management may be an important part of the treatment plan (Garcia, 2014; Lee et al., 2014). In conclusion, our findings contribute new knowledge to the growing literature on aging and decision making. Ultimately, we aim to promote physical, mental, and financial health across the life span.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences online.

Funding

This research was partly supported by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG024962) and the European Union (FP7-PEOPLE-2013-CIG 618522).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caezilia Loibl, Faisal Muqdat, Simon McNair, Barbara Summers, and Andrea Taylor for comments.

References

- Baltes P. B., Lindenberger U., & Staudinger U. M (2006). Life-span theory in developmental psychology. In Lerner R. M. & Damon W. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed, Vol. 1, pp. 569–664). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W., Parker A. M., & Fischhoff B (2007). Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 938–956. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W., Parker A. M., & Strough J (2016). Choosing to be happy? Age differences in “maximizing” decision strategies and experienced emotional well-being. Psychology and Aging, 31, 295–300. doi:10.1037/pag0000073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W., Strough J., & Parker A. M (2014). Getting older isn’t all that bad: Better decisions and coping when facing “sunk costs”. Psychology and Aging, 29, 642–649. doi:10.1037/a0036308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E., Sarkisian N., & Tamborini C. R (2013). Causal effects of retirement timing on subjective physical and emotional health. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 73–84. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science (New York, N.Y.), 312, 1913–1915. doi:10.1126/science.1127488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L., & Lang F. R (1996). Future Time Perspective (FTP) Scale. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University; Retrieved from https://lifespan.stanford.edu/projects/future-time-perspective-ftp-scale [Google Scholar]

- Chapman G. B. (2000). Preferences for improving and declining sequences of health outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 203–218. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(200004/06)13:2<203::AID-BDM317>3.0.CO;2-S [Google Scholar]

- Charles S. T., & Luong G (2013). Emotional experience across adulthood: The theoretical model of strength and vulnerability integration. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 22, 443–448. doi:10.1177/0963721413497013 [Google Scholar]

- Delaney R., Strough J., Parker A. M. & Bruine de Bruin W. B (2015). Variations in decision-making profiles by age and gender: A cluster-analytic approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet A., Lau-Gesk L., & Scott C (2011). The influence of aging on preferences for sequences of mixed affective events. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 24, 293–314. doi:10.1002/bdm.695 [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S., & Smith J (2013). Preference for increasing wages: How do people value various streams of income?Judgment and Decision Making, 8, 74–90. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1631845 [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. S. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi A., & Kuehlwein M (2016). Reexamining income tax overwithholding as a response to uncertainty. Public Finance Review, 44, 220–244. doi:10.1177/1091142114539750 [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S. (2014). The effects of education on anxiety levels in patients receiving chemotherapy for the first time: An integrative review. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 516–521. doi:10.1188/14.CJON.18-05AP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 214–219. doi:10.1111/1467–8721.00152 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hess T. M. (2014). Selective engagement of cognitive resources: Motivational influences on older adults’ cognitive functioning. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 9, 388–407. doi:10.1177/1745691614527465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz D. M., & Ossenfort K. L (2017). Aging, attention and situation selection: Older adults create mixed emotional environments. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 15, 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John D., & Lang F. R (2015). Subjective acceleration of time experience in everyday life across adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1824–1839. doi:10.1037/dev0000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. The American Psychologist, 58, 697–720. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Gesk L. (2005). Understanding consumer evaluations of mixed affective experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 32, 23–28. doi:10.1086/429598 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Park H. Y., Jung D., Moon M., Keam B., & Hahm B. J (2014). Effect of brief psychoeducation using a tablet PC on distress and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A pilot study. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 928–935. doi:10.1002/pon.3503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gao J., Enkavib A. Z., Zavalb L., Weber E. U., & Johnson E. J (2014). Sound credit scores and financial decisions despite cognitive aging. Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, 112, 65–69. doi:10.1073/pnas.1413570112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U., von Oertzen T., Ghisletta P., & Hertzog C (2011). Cross-sectional age variance extraction: What’s change got to do with it?Psychology and Aging, 26, 34–47. doi:10.1037/a0020525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff C. E., Reed A. E., & Maresca S. N (2012). Who saves the best for last? Age differences in preferences for affective sequences. Psychology and Aging, 27, 840–848. doi:10.1037/a0028747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff C. E., Rutt J. L., Samanez-Larkin G. L., O’Donoghue T., & Reyna V. E (2017). Preferences for temporal sequences of real outcomes differ across domains but do not vary by age. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. Advance Access publication July 8, 2017. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. F. (1987). Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. The Economic Journal, 97, 666–684. doi:10.2307/2232929 [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. F., Weber E. U., Hsee C. K., & Welch N (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G., & Prelec D (1993). Preferences over outcome sequences. Psychological Review, 100, 91–108. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.1.91 [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G., & Sicherman N (1991). Do workers prefer increasing wage profiles?Journal of Labor Economics, 9, 67–84. doi:10.1086/298259 [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell S. E., & Cole D. A (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12, 23–44. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E., & Bruine de Bruin W (2012). Aging and decision skills. In Dhami M. K., Schlottmann A., & Waldmann M. (Eds.), Judgment and decision making as a skill: Learning, development, and evolution. (pp. 113–135). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters E., Hess T. M., Västfjäll D., & Auman C (2007). Adult age differences in dual information processes: Implications for the role of affective and deliberative processes in older adults’ decision making. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 2, 1–23. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretz J. E., Brookings J. B., Carlson L. A., Humbert T. K., Roy M., Jones M., & Memmert D (2014). Development and validation of a new measure of intuition: The Types of Intuition Scale. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27, 454–467. doi:10.1002/bdm.1820 [Google Scholar]

- Prelec D., & Loewenstein G (1998). The red and the black: Mental accounting of savings and debt. Marketing Science, 17, 4–28. doi:10.1287/mksc.17.1.4 [Google Scholar]

- Purcell P. J. (2010). Older workers: Employment and retirement trends. Journal of Pension Planning and Compliance, 36, 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Read D., & Powell M (2002). Reasons for sequence preferences. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 433–460. doi:10.1002/bdm.429 [Google Scholar]

- Rendell P. G., Bailey P. E., Henry J. D., Phillips L. H., Gaskin S.&Kliegel M (2012). Older adults have greater difficulty imagining future rather than atemporal experiences. Psychology and Aging, 27, 1089–1098. doi:10.1037/a0029748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roalf D. R., Mitchell S. H., Harbaugh W. T., & Janowsky J. S (2012). Risk, reward, and economic decision making in aging. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 289–298. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 140–144. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00293.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter D. L., Gaesser B., & Addis D. R (2013). Remembering the past and imagining the future in the elderly. Gerontology, 59, 143–151. doi:10.1159/000342198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie K.W. (1983). Longitudinal studies of adult psychological development. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. G., & Bruce R. A (1995). Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55, 818–831. doi:10.1177/ 0013164495055005017 [Google Scholar]

- Strough J., Bruine de Bruin W., Parker A. M., Karns T., Lemaster P., Pichayayothin N. … Stoiko R (2016). What were they thinking? Reducing sunk-cost bias in a life-span sample. Psychology and Aging, 31, 724–736. doi:10.1037/pag0000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J., Bruine de Bruin W., Parker A. M., Lemaster P., Pichayayothin N., & Delaney R (2016). Hour glass half full or half empty? Future time perspective and preoccupation with negative events across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 31, 558–573. doi:10.1037/pag0000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J., Karns T. E., & Schlosnagle L (2011). Decision-making heuristics and biases across the life span. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1235, 57–74. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06208.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J., Parker A. M., & Bruine de Bruin W (2015). Understanding life-span developmental changes in decision-making competence. In Hess T., Strough J., & Löckenhoff C. (Eds.), Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strough J., Schlosnagle L., & DiDonato L (2011). Understanding decisions about sunk costs from older and younger adults’ perspectives. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 681–686. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo K., Forder P. M., Tavener M., Rodgers B., Banks E., Bauman A., & Byles J. E (2015). Retirement, age, gender and mental health: Findings from the 45 and Up Study. Aging and Mental Health, 19, 647–657. doi:10.1080/13607863.2014. 962002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K. E., Kwong J. Y., & Ng C. K (2008). When thinking rationally increases biases: The role of rational thinking style in escalation of commitment. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 246–271. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00309.x [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.