Abstract

Background: U.S. women of ages 50–74 years are recommended to receive screening mammography at least biennially. Our objective was to evaluate multilevel predictors of nonadherence among screened women, as these are not well known.

Materials and Methods: A cohort study was conducted among women of ages 50–74 years with a screening mammogram in 2011 with a negative finding (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System 1 or 2) within Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium research centers. We evaluated the association between woman-level factors, radiology facility, and PROSPR research center, and nonadherence to breast cancer screening guidelines, defined as not receiving breast imaging within 27 months of an index screening mammogram. Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Results: Nonadherence to guideline-recommended screening interval was 15.5% among 51,241 women with a screening mammogram. Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander women, women of other races, heavier women, and women of ages 50–59 years had a greater odds of nonadherence. There was no association with ZIP code median income. Nonadherence varied by research center and radiology facility (variance = 0.10, standard error = 0.03). Adjusted radiology facility nonadherence rates ranged from 10.0% to 26.5%. One research center evaluated radiology facility communication practices for screening reminders and scheduling, but these were not associated with nonadherence.

Conclusions: Breast cancer screening interval nonadherence rates in screened women varied across radiology facilities even after adjustment for woman-level characteristics and research center. Future studies should investigate other characteristics of facilities, practices, and health systems to determine factors integral to increasing continued adherence to breast cancer screening.

Keywords: breast cancer, guideline adherence, mammography, screening

Introduction

Breast cancer screening is an essential preventive care service for cancer control in the United States. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends breast cancer screening biennially for average-risk women 50–74 years of age based on evidence supporting the potential health benefits outweighing the harms.1 Although other professional societies and groups recommend varying screening intervals,2–4 there is clinical consensus across all groups for breast cancer screening at least every 2 years among women 50–74 years of age. However, not all women achieve this screening recommendation. Approximately 72% of U.S. women of ages 50–74 years reported receiving mammography within 2 years in 2015,5 despite a Healthy People 2020 goal of 81.1% of women being up to date with recommended breast cancer screening.6

The vast majority of previous studies and population-level estimates of breast cancer screening measure one-time screening,5,7–9 yet for breast cancer screening to be effective, women must return for screening at the appropriate interval. Maintenance of mammography, or adherence, is important to measure to determine if women are receiving guideline-concordant care and to identify barriers to continuing screening after a previous screening episode. Moreover, evaluating predictors of nonadherence to breast cancer screening guidelines among screened women is critical for developing targeted interventions to improve screening adherence and ultimately to decrease breast cancer mortality. Numerous prior studies have evaluated woman-level characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status,7–11 but fewer studies have assessed the role of health care systems, radiology facilities, and facilities' communication practices on breast cancer screening adherence.12–17 Communication between radiology facilities, providers, and patients is necessary for conveying the appropriate breast cancer screening interval, and ineffective communication could contribute to failures in mammography maintenance. A multilevel perspective of cancer screening processes—considering the influences of individuals, providers, facilities, and health systems—is increasingly being recognized by health care delivery researchers as an important approach to better understand the steps and interfaces required to successfully complete the entire cancer screening process,18–21 and for continued adherence to cancer screening.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the influence of multilevel characteristics across different health care settings on nonadherence to breast cancer screening recommendations among women 50–74 years of age who received an initial screening examination with negative results.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This cohort study was conducted as part of the National Cancer Institute-funded consortium Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR).22 The overall aim of PROSPR is to conduct multisite coordinated transdisciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening processes. The 10 PROSPR research centers reflect the diversity of U.S. delivery system organizations. Our analyses included the following breast cancer research centers: the University of Vermont breast cancer research center (VT), which includes data from all women receiving breast imaging in the state of Vermont via the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System, and the Dartmouth-Brigham and Women's Hospital research center that captures data on women with a primary care visit within the primary care practice networks at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in New Hampshire (DH) and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) in Massachusetts.

Women of ages 50–74 years were eligible if they received a screening mammogram in 2011 with an initial Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) assessment of 1 or 2 (negative or benign finding),23 had no additional imaging on the same day as the mammogram, no recommendation for further work-up, no prior breast cancer diagnosis, and at least 27 months of follow-up after the mammogram. We defined a screening mammogram as a bilateral mammogram with a screening indication and no other breast imaging 3 months prior. We classified a woman's first screening examination in 2011 as the index screen. Prior breast cancer diagnoses were identified from electronic health records (EHR), self-report, and cancer registry data. All activities were approved by the institutional review boards at the PROSPR Statistical Coordinating Center and the research centers.

Measures and data sources

We obtained breast imaging data (imaging date, mammogram type [standard two-dimensional and/or digital breast tomosynthesis], laterality, indication for examination, BI-RADS assessment, and recommendation for further work-up) from January 2011 through September 2014 from radiology reports, billing data, and data extracts from facilities' radiology information systems. We defined nonadherence to breast cancer screening guidelines as not receiving breast imaging in the 27 months following the index screen. The adherent group included women receiving imaging within 27 months, regardless of indication, because our goal was to identify women in need of screening within the recommended interval.24 We allowed for an additional 3 months post 2 years to account for scheduling issues and to align with a Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set breast cancer screening adherence metric.25

We evaluated multilevel factors that were available in our data with limited missing values and were likely to be associated with screening nonadherence a priori. We assessed the following characteristics from EHR and self-reported data using the categories described in Table 2: age at the index screening examination, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI) in 2011, annual median household income of the ZIP code of residence in 2011 derived from the American Community Survey,26 PROSPR research center, and radiology facility.

Table 2.

Multivariable-Adjusted Odds Ratios of Women Not Receiving Breast Imaging Within 27 Months of an Index Screening Mammogram

| Adjusted ORa | 95% CI | Overall, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| Woman level | |||

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||

| 50–59 | Ref. | ||

| 60–69 | 0.74 | 0.70–0.78 | |

| 70–74 | 0.87 | 0.79–0.94 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| NH white | Ref. | ||

| NH black | 1.21 | 0.98–1.48 | |

| NH Asian/PI | 1.31 | 1.01–1.70 | |

| NH other | 1.58 | 1.30–1.93 | |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.84–1.17 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | ||

| <25 | Ref. | ||

| 25 – <30 | 1.07 | 0.99–1.14 | |

| 30 – <35 | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 | |

| 35+ | 1.31 | 1.21–1.42 | |

| ZIP code median income (quartiles) | 0.094 | ||

| <$47,225 | 1.08 | 0.97–1.20 | |

| $47,225–55,803 | 1.09 | 0.99–1.21 | |

| $55,804–71,836 | 1.12 | 1.03–1.23 | |

| >$71,836 | Ref. | ||

| PROSPR research centerb | |||

| VT | Ref. | 0.021 | |

| DH | 0.96 | 0.64–1.44 | |

| BWH | 0.62 | 0.44–0.87 | |

| Random effectc | |||

| Radiology facility | |||

| Variance | 0.0998 | ||

| Standard error | 0.0335 | ||

| Median odds ratio | 1.35 | ||

ORs are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, income, and PROSPR research center.

DH and BWH are two primary care practice networks that comprise one PROSPR research center.

p-value <0.001 for likelihood ratio test comparing the multilevel mixed-effects model to ordinary logistic regression. Includes 26 radiology facilities (DH n = 3, BWH n = 7, VT n = 16 facilities within 13 radiology practices).

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

We had the opportunity to further evaluate radiology facility communication practices in more detail at the VT research center, which had a unique focus on radiology facilities' influence on the screening process. We used cross-sectional radiology facility survey data27 from 2015 to assess the following communication practices that we believed a priori could be associated with screening nonadherence and had sufficient variability across facilities: (1) sending patients a reminder of an upcoming scheduled mammogram, (2) sending patients a reminder of when the next mammogram is due (if not scheduled), (3) scheduling the next screening examination at the time of the current mammogram, and (4) sending providers a reminder of when patients are due for their next mammogram. Schapira et al.27 describe additional details of the radiology facility survey.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportion of women with each characteristic in the total population and the proportion nonadherent. Among all women, we used multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression to calculate (1) multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of nonadherence to breast cancer screening guidelines and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for woman-level (age, race/ethnicity, BMI, and ZIP code median income) and research center fixed effects and (2) the variance, standard error, and median OR of the random effect (radiology facility). The median OR estimated the unexplained variation between facilities.28,29 We adjusted the model for all woman-level characteristics and research center. We performed an omnibus Wald test for each of the fixed effects and tested the benefit of adding random effects with a likelihood ratio test comparison with a fixed model without random effects.

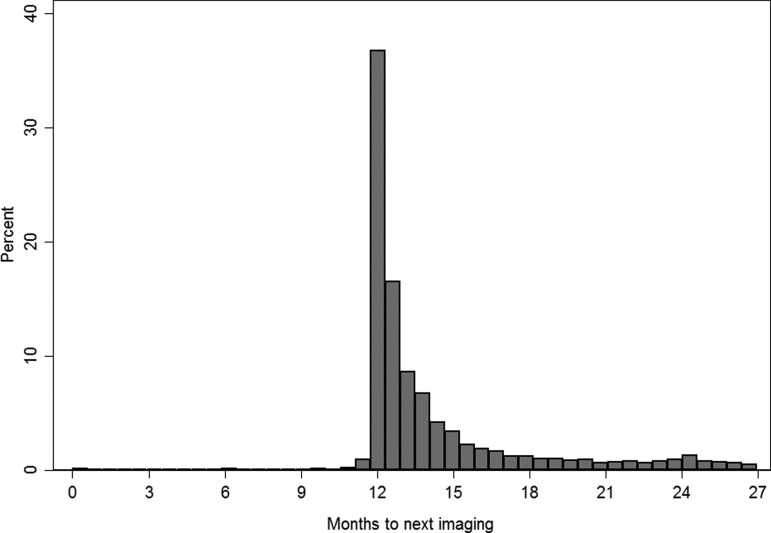

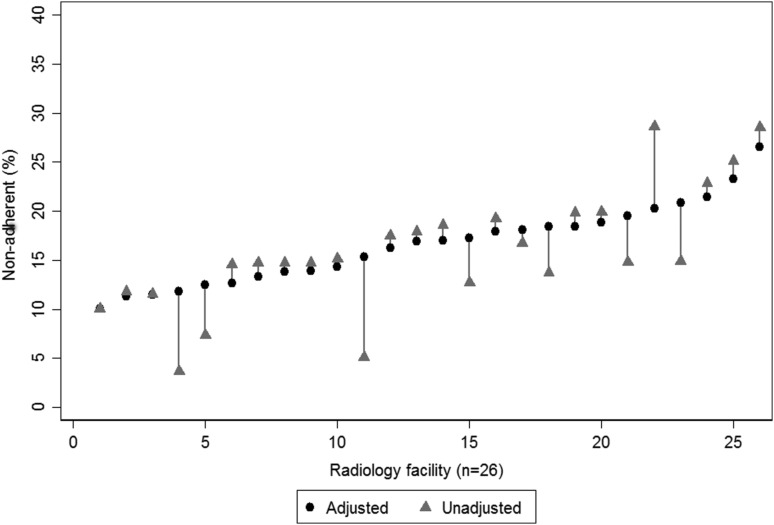

For each radiology facility, we calculated the unadjusted proportion of women nonadherent and the proportion nonadherent adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, income, and research center using a random effects model. The adjusted proportion represented the probability of nonadherence if all other characteristics were fixed and a woman attended a different facility. We displayed the distribution of the number of months from the index screen to the next imaging among women who were adherent.

We conducted a multivariable analysis of radiology facility communication practices within VT radiology facilities. Because of potential collinearity of communication characteristics, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare a logistic regression model with all woman-level characteristics to models with each communication characteristic added individually. We then added communication characteristics that were individually statistically significant sequentially to the model. The final multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model included all woman-level characteristics and three of the four radiology facility-level communication characteristics as fixed effects and radiology facility as a random effect. The characteristic, “Sends providers a reminder of when patients are due for their next mammogram,” was not statistically significant and, therefore, not included in the final model. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were completed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

There were 51,241 women with an index screening examination in 2011 and 15.5% were nonadherent with screening interval guidelines after 27 months of follow-up. Almost all index screening examinations were standard two-dimensional mammograms (n = 29 women received digital breast tomosynthesis combined with digital mammography). Compared with adherent women, nonadherent women were more likely to be 50–59 years of age, have a higher BMI, and have a lower ZIP code median income, but less likely to be non-Hispanic white or receive an index screening examination at BWH (Table 1). Among women who were adherent with screening interval guidelines, there was a peak in returning for imaging ∼12 months after the index screen, with only a small proportion of women receiving imaging from 24 to 27 months (Fig. 1; median = 12.6 months to next imaging; 4.2% of women received imaging from 24 to 27 months).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Women Receiving a 2011 Index Screening Mammogram

| Adherent (N = 43,312) | Nonadherenta(N = 7,929) | Total (N = 51,241) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | Nonadherenta(row %) | N | (column %) | |

| Woman level | |||||

| Age at index screening mammogram, years | |||||

| 50–59 | 20,963 | 4,344 | 17.2 | 25,307 | 49.4 |

| 60–69 | 17,551 | 2,728 | 13.5 | 20,279 | 39.6 |

| 70–74 | 4,798 | 857 | 15.2 | 5,655 | 11.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| NH white | 39,462 | 7,107 | 15.3 | 46,569 | 91.9 |

| NH black | 947 | 210 | 18.2 | 1,157 | 2.3 |

| NH Asian/PI | 428 | 92 | 17.7 | 520 | 1.0 |

| NH Am Ind/AK Native | 60 | 24 | 28.6 | 84 | 0.2 |

| NH other | 64 | 19 | 22.9 | 83 | 0.2 |

| NH multiple races | 354 | 100 | 22.0 | 454 | 0.9 |

| Hispanic | 1,568 | 251 | 13.8 | 1,819 | 3.6 |

| Missing | 429 | 126 | 555 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) in 2011 | |||||

| <25 | 14,454 | 2,371 | 14.1 | 16,825 | 36.4 |

| 25 – <30 | 12,055 | 2,110 | 14.9 | 14,165 | 30.7 |

| 30 – <35 | 7,076 | 1,341 | 15.9 | 8,417 | 18.2 |

| 35+ | 5,524 | 1,236 | 18.3 | 6,760 | 14.6 |

| Missing | 4,203 | 871 | 5,074 | ||

| ZIP code median income (quartiles) in 2011 | |||||

| <$47,225 | 11,235 | 2,244 | 16.7 | 13,479 | 26.8 |

| $47,225–55,803 | 10,739 | 2,151 | 16.7 | 12,890 | 25.7 |

| $55,804–71,836 | 10,537 | 1,874 | 15.1 | 12,411 | 24.7 |

| >$71,836 | 9,982 | 1,475 | 12.9 | 11,457 | 22.8 |

| Missing | 819 | 185 | 1,004 | ||

| First BI-RADS assessment of the index screening mammogram | |||||

| BI-RADS 1 | 35,992 | 6,477 | 15.3 | 42,469 | 82.9 |

| BI-RADS 2 | 7,320 | 1,452 | 16.6 | 8,772 | 17.1 |

| PROSPR research centerb | |||||

| VT | 31,576 | 5,853 | 15.6 | 37,429 | 73.0 |

| DH | 5,484 | 1,077 | 16.4 | 6,561 | 12.8 |

| BWH | 6,252 | 999 | 13.8 | 7,251 | 14.2 |

Nonadherent to breast cancer screening guidelines is defined as not receiving breast imaging within 27 months of an index screening mammogram.

DH and BWH are two primary care practice networks that comprise one PROSPR research center.

Am Ind/AK Native, American Indian/Alaska Native; BI-RADS, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; BMI, body mass index; BWH, Brigham and Women's Hospital; DH, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System; NH, non-Hispanic; PI, Pacific Islander; PROSPR, Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens; VT, Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

FIG. 1.

Months to next imaging after an index screening mammogram among women receiving breast imaging within 27 months of an index screen.

After multivariable adjustment, women of ages 50–59 years had a greater odds of nonadherence than women of ages 60–74 years (ages 60–69 years: OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.70–0.78; ages 70–74 years: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.79–0.94; Table 2). Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander women and women of “other” races had a greater odds of nonadherence compared with non-Hispanic white women, although numbers were small. Nonadherence increased with BMI. ZIP code median income was not statistically significantly associated with nonadherence (p = 0.094). Women receiving screening in VT had a greater odds of nonadherence relative to BWH women, but no statistically significant difference relative to DH women. We observed statistically significant variation in nonadherence between the 26 radiology facilities after adjusting for woman-level factors and research center (variance = 0.10; standard error = 0.03; median OR = 1.35). Unadjusted nonadherence rates ranged from 3.7% to 28.6% across facilities (median = 14.8%; interquartile range [IQR] = 12.7%–19.2%; Fig. 2). After adjustment for women's characteristics and research center, facilities' nonadherence rates ranged from 10.0% to 26.5% (median = 16.9%; IQR = 13.3%–18.8%).

FIG. 2.

Paired multivariable-adjusted and unadjusted percent of women not receiving breast imaging within 27 months of an index screening mammogram by radiology facility. Note: The number of women at each facility ranges from n = 35 to n = 8,029. For each facility, the gray line connects the unadjusted nonadherence percent (gray triangle) to the percent nonadherent (black circle) after adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index, ZIP code median income, and Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens research center.

We further evaluated the role of radiology facility communication characteristics on screening interval nonadherence within the 15 VT radiology facilities with communication information. Nonadherent women were less likely than adherent women to attend radiology facilities that sent patient reminders about mammograms scheduled or due, but more likely to attend facilities that scheduled the next screening examination during the current mammogram (Table 3). However, after multivariable adjustment there was no association between any of the communication practices and nonadherence. Yet, there was statistically significant variation in nonadherence by VT radiology facility (variance = 0.10; standard error = 0.04; median OR = 1.35). Results were generally comparable when including each communication practice in a separate multivariable-adjusted mixed-effects model (results not shown).

Table 3.

Associations Between Radiology Facility Characteristics and Women Not Receiving Breast Imaging Within 27 Months of an Index Screening Mammogram in Vermont

| Adherent (N = 31,576) | Nonadherent (N = 5,853) | Total (N = 37,429) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiology facility characteristicsa | N | N | Nonadherent (row %) | N | (column %) | Adjusted ORb | 95% CI |

| Fixed effects | |||||||

| Sends patients a reminder of an upcoming scheduled mammogram | |||||||

| No | 10,141 | 2,195 | 17.8 | 12,336 | 33.0 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 21,410 | 3,648 | 14.6 | 25,058 | 67.0 | 0.98 | 0.60–1.60 |

| Missing | 25 | 10 | 35 | ||||

| Sends patients a reminder of when the next mammogram is due (if not scheduled) | |||||||

| No | 7,096 | 1,599 | 18.4 | 8,695 | 23.3 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 24,455 | 4,244 | 14.8 | 28,699 | 76.7 | 0.81 | 0.46–1.41 |

| Missing | 25 | 10 | 35 | ||||

| Schedules the next screening examination at the time of the current mammogram | |||||||

| No | 28,796 | 5,197 | 15.3 | 33,993 | 90.9 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 2,755 | 646 | 19.0 | 3,401 | 9.1 | 1.07 | 0.66–1.76 |

| Missing | 25 | 10 | 35 | ||||

| Sends providers a reminder of when patients are due for their next mammogram | |||||||

| No | 19,834 | 3,517 | 15.1 | 23,351 | 62.4 | — | |

| Yes | 11,717 | 2,326 | 16.6 | 14,043 | 37.6 | — | |

| Missing | 25 | 10 | 35 | ||||

| Random effectc | |||||||

| Radiology facility | |||||||

| Variance | 0.0979 | ||||||

| Standard error | 0.0383 | ||||||

| Median odds ratio | 1.35 | ||||||

Includes women from 15 radiology facilities with radiology survey data within 13 radiology practices. Nonadherent to breast cancer screening guidelines is defined as not receiving breast imaging within 27 months of an index screening mammogram.

ORs are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index, ZIP code median income, sending a reminder of an upcoming mammogram, sending a reminder of when the next mammogram is due, and scheduling the next screening examination at the time of the current mammogram.

p-value <0.001 for likelihood ratio test comparing the multilevel mixed-effects model to ordinary logistic regression.

Discussion

Continued mammography use after a negative screening mammogram result is necessary for women to retain the benefits from breast cancer screening over time. Our study used multilevel data from varied health care settings and found that almost 16% of women of ages 50–74 years who received screening with negative findings did not return for imaging within 27 months. The odds of nonadherence to recommended screening intervals varied by sociodemographic factors, research center, and radiology facility, and woman-level factors did not explain the variation observed across research centers or radiology facilities.

Prior studies have evaluated screening nonadherence and woman-level characteristics, such as age, race/ethnicity, BMI, and income. In contrast to our findings that women of ages 50–59 years had a greater odds of nonadherence, previous studies including women of ages 50–74 years suggest that either older women are more likely to be nonadherent than younger women7,10 or there is no difference by age.5 Differences may be due to varying age categories or populations studied. In addition, differences may relate to a cohort effect—women in their 50s in earlier studies received mammography during a period of consensus about the benefits of annual screening, whereas women of ages 50–59 years in studies that are more recent received screening during a time of controversy about appropriate screening intervals.

With respect to race/ethnicity, the most recent National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) observed the lowest levels of recent breast cancer screening among American Indians and Alaska Natives, followed by Asians.5 Our screening nonadherence findings by race/ethnicity generally align with NHIS, although we could not evaluate American Indians and Alaska Natives separately. Systematic reviews evaluating obesity and mammography use found either no association with mammography completion8 or an increased likelihood of nonadherence among obese white women, but no association or a less pronounced association with obesity among black women.30 Our BMI results are comparable with these findings given that our population was predominantly non-Hispanic white. Greater screening nonadherence among racial/ethnic minority groups and women with a higher BMI may be due to a lack of targeted interventions to promote adherence or to a negative experience with the index mammogram in these groups.

We assessed the median income of the ZIP code of residence as a proxy for socioeconomic status and hypothesized that women living in ZIP codes with lower median incomes may have greater screening nonadherence and could potentially benefit from targeted screening interventions. However, we did not observe greater nonadherence among low-income women after multivariable adjustment, as has been shown in other studies.5,8 This could be due to our measure of ZIP code income, rather than woman-level income, or to increased access to breast cancer screening for low-income women in Vermont and Massachusetts through statewide programs.31,32 Future studies with more granular income data should consider income at various levels (e.g., woman level and community level) and evaluate how different levels influence screening nonadherence. Prior studies identified other woman-level characteristics that were associated with nonadherence or less mammography use that we could not evaluate, such as being less educated,5,7,8,33 uninsured,5,7,8,34,35 a recent immigrant,5,8 without a usual source of care,5,7,34 without physician-recommended mammography,8 having increased comorbidity or fair/poor health,9,11,33 and having no family history of breast cancer.8,10,35

Notably, nonadherence to recommended screening intervals varied by research center and radiology facility in our study, even after adjustment for women's characteristics. The greater odds of nonadherence at the VT research center compared with BWH may be because VT contains all radiology facilities in the state, which are part of numerous distinct health systems that predominantly consist of rural community hospitals. In contrast, BWH is a unified health system with system-level screening recommendations and EHR screening support capabilities, such as patient tracking and reminders for patients and providers. Although facility characteristic data were unavailable across all research centers, the substantial range in nonadherence rates at DH, BWH, and VT radiology facilities underscores the importance of factors beyond the woman level on mammography maintenance. Possible radiology facility factors that could influence nonadherence include screening interval protocols, patient tracking procedures, and/or communication practices.

VT radiology facilities sending mammogram reminders to patients or scheduling the next examination at the time of a screening examination did not affect the odds of screening nonadherence in our study. This absence of observed associations could be due to unmeasured facility-level factors. Previous radiology facility studies found that sending reminder letters of when the next mammogram is due increased repeat mammography,15,16 whereas some,12,14 but not all studies,17 suggest that multimodal approaches using letters and telephone calls may be most effective in increasing subsequent mammography. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to promote repeat mammography that included some of these studies could not conclude that using reminders within health care settings was superior to other intervention types due to heterogeneity of study effect sizes.36 This finding reinforces the need for further studies to determine the key drivers that increase repeat mammography. Other potential contextual factors of interest may be accepting self-referrals,13 having flexible mammography appointment times,37 and having strong organizational commitment to performance and quality of care.37 In addition, targeted screening reminders for specific groups of women (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities and obese women) may be necessary for reminders to be effective.38

Women's interactions with primary care may also affect screening interval nonadherence rates. Primary care providers and practices play an essential role in recommending regular screening mammography to their patients. Studies demonstrate that increased breast cancer screening is associated with receiving a recommendation from a provider,8,37 notifying primary care providers that patients are due for screening,13 having longer continuity of care with a primary care provider,39 and having greater patient satisfaction with patient–provider communication.39,40 Organizational factors within primary care practices also influence mammography screening—availability of comprehensive preventive services,39 sufficient resources for clinical staffing,41 and authority in determining policies and procedures all increase the odds of screening.41 Furthermore, primary care practices may endorse screening intervals that conflict with USPSTF-recommended or radiology facility-recommended intervals,42 potentially leading to variability in screening nonadherence rates. Although we were unable to evaluate primary care features in our study, future studies should evaluate primary care communication practices, as screening adherence falls under the purview of both radiology and primary care.

In our study, most women who were adherent with screening recommendations received imaging closer to an annual schedule, rather than biennially as recommended by the USPSTF. Other studies also observe substantial levels of annual screening among U.S. women,42–44 suggesting that (1) patients prefer annual screening and/or (2) radiology facilities and/or providers may recommend annual screening to their patients. All VT radiology facilities that sent patients screening reminders in our study sent them annually. Discordance between guideline-recommended screening intervals and reminders from radiology facilities could lead to potentially greater screening nonadherence. Future alignment between guideline-recommended screening intervals and screening reminders for patients is warranted.

Some study limitations may affect interpretation of our results. Because we evaluated screening nonadherence within a population with previous screening, our findings are not generalizable to the general population that includes never screeners. Thus, we cannot infer that predictors of screening adherence will also be associated with screening initiation. Incomplete capture of imaging could influence our estimates of screening interval nonadherence and research center comparisons if women moved out of a research center's catchment area (VT) or received imaging outside of the primary care practice network (DH and BWH). This would lead to an overestimate of the proportion of women nonadherent to screening interval guidelines. Family history of breast cancer, comorbidity status, radiology facility characteristics, primary care provider and practice characteristics, and community features may have influenced screening nonadherence, but these factors were unavailable at all research centers. In addition, radiology facility communication characteristics at the VT research center were collected in 2015 after breast imaging data (2011–2014); yet, communication practices remained consistent for this period. Finally, we had limited power to detect associations with VT radiology facility communication characteristics and these data are susceptible to selection bias if facilities with low screening adherence rates implemented communication strategies to improve rates, whereas facilities with high adherence rates did not. Study strengths include our multilevel analysis of different health care settings, radiology facilities, and novel radiology facility communication data that are unavailable in EHR. In addition, rather than measuring initial mammography use, we assessed mammography use among women already receiving a previous screening examination, thus allowing for inferences about predictors of mammography maintenance.

Conclusions

This study showed variation in nonadherence to breast cancer screening guidelines at multiple levels—woman, radiology facility, and research center—among women who received prior screening with negative findings. Radiology facilities demonstrated variation in rates of nonadherence to recommended screening intervals even after accounting for woman-level factors and research center. Additional research is needed to characterize the features of radiology facilities and primary care practices that may increase breast cancer screening adherence among women with a screening history. Future studies using multilevel approaches could identify mutable characteristics of facilities, practices, and/or health systems that improve breast cancer screening adherence without increasing patient burden among women who are least likely to maintain biennial screening.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) research centers for the data they have provided for this study. A list of PROSPR investigators and contributing research staff is provided at website (http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/prospr). They also thank Hannah Wang for her assistance with the literature review for this article. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute-funded PROSPR consortium (Grant Nos. U01CA163304, U54CA163303, U54CA163307, U54CA163313, and U54CA163261).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: On Behalf of the PROSPR consortium

Authors' Contributions

Conception or design (E.F.B., B.L.S., A.N.A.T., J.S.H., C.I.L., C.D.L., and W.E.B.); acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data (E.F.B., B.L.S., A.N.A.T., J.S.H., T.O., M.M.S., A.M.M., C.I.L., S.D.H., C.D.L., K.J.W., and W.E.B.); drafting of the article (E.F.B.); critical revision of the article for important intellectual content (E.F.B., B.L.S., A.N.A.T., J.S.H., T.O., M.M.S., A.M.M., C.I.L., S.D.H., C.D.L., K.J.W., and W.E.B.); statistical analysis (E.F.B. and W.E.B.); obtaining funding (B.L.S., A.N.A.T., J.S.H., T.O., and W.E.B.); administrative, technical, or material support (E.F.B., B.L.S., A.N.A.T., J.S.H., T.O., and W.E.B.); and supervision (E.F.B. and W.E.B.).

Author Disclosure Statement

C.D.L. received research funding from GE Healthcare. All other authors have no financial disclosures to report. C.D.L. is a member of the Advisory Board for GE Healthcare. Grant support for this work is included in the Acknowledgements section.

References

- 1. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:279–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin number 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e1–e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mainiero MB, Lourenco A, Mahoney MC, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria breast cancer screening. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:R45–R49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. J Am Med Assoc 2015;314:1599–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White A, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Cancer screening test use—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:201–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov Accessed June11, 2018

- 7. Mack KP, Pavao J, Tabnak F, Knutson K, Kimerling R. Adherence to recent screening mammography among Latinas: Findings from the California Women's Health Survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: A systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1477–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vinikoor LC, Lavinder E, Marsh GM, Steffes SM, Schenck AP. Predictors of screening mammography among a North and South Carolina Medicare population. Am J Med Qual 2011;26:364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borrayo EA, Hines L, Byers T, et al. Characteristics associated with mammography screening among both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1585–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gierisch JM, Earp JA, Brewer NT, Rimer BK. Longitudinal predictors of nonadherence to maintenance of mammography. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1103–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bodiya A, Vorias D, Dickson HA. Does telephone contact with a physician's office staff improve mammogram screening rates? Fam Med 1999;31:324–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Engelman KK, Ellerbeck EF, Mayo MS, Markello SJ, Ahluwalia JS. Mammography facility characteristics and repeat mammography use among Medicare beneficiaries. Prev Med 2004;39:491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feldstein AC, Perrin N, Rosales AG, et al. Effect of a multimodal reminder program on repeat mammogram screening. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mayer JA, Lewis EC, Slymen DJ, et al. Patient reminder letters to promote annual mammograms: A randomized controlled trial. Prev Med 2000;31:315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quinley J, Mahotiere T, Messina CR, Lee TK, Mikail C. Mammography-facility-based patient reminders and repeat mammograms for Medicare in New York State. Prev Med 2004;38:20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rakowski W, Lipkus IM, Clark MA, et al. Reminder letter, tailored stepped-care, and self-choice comparison for repeat mammography. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:308–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beaber EF, Kim JJ, Schapira MM, et al. Unifying screening processes within the PROSPR consortium: A conceptual model for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;2012:2–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taplin SH, Yabroff KR, Zapka J. A multilevel research perspective on cancer care delivery: The example of follow-up to an abnormal mammogram. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:1709–1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zapka J, Taplin SH, Ganz P, Grunfeld E, Sterba K. Multilevel factors affecting quality: Examples from the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;2012:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR). Available at: http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/prospr Accessed June11, 2018

- 23. D'Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA. ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chubak J, Hubbard R. Defining and measuring adherence to cancer screening. J Med Screen 2016;23:179–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Breast cancer screening: Percentage of women 50 to 74 years of age who had a mammogram to screen for breast cancer. Available at: www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/summaries/summary/50438 Accessed June11, 2018

- 26. American Community Survey (ACS). Available at: www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs Accessed June11, 2018

- 27. Schapira MM, Barlow WE, Conant EF, et al. Communication practices of mammography facilities and timely follow-up of a screening mammogram with a BI-RADS 0 assessment. Acad Radiol 2018;25:1118–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsen K, Petersen JH, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Endahl L. Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics 2000;56:909–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: Using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:290–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen SS, Palmieri RT, Nyante SJ, et al. Obesity and screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in women: A review. Cancer 2008;112:1892–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vermont Department of Health. Ladies First. Available at: http://ladiesfirst.vermont.gov Accessed June11, 2018

- 32. Doonan MT, Tull KR. Health care reform in Massachusetts: Implementation of coverage expansions and a health insurance mandate. Milbank Q 2010;88:54–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hubbard RA, O'Meara ES, Henderson LM, et al. Multilevel factors associated with long-term adherence to screening mammography in older women in the U.S. Prev Med 2016;89:169–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rakowski W, Meissner H, Vernon SW, Breen N, Rimer B, Clark MA. Correlates of repeat and recent mammography for women ages 45 to 75 in the 2002 to 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 2003). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2093–2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Palmer JR, Horton NJ, Adams-Campbell LL. A multilevel study of socioeconomic predictors of regular mammography use among African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:2628–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vernon SW, McQueen A, Tiro JA, del Junco DJ. Interventions to promote repeat breast cancer screening with mammography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1023–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Plourde N, Brown HK, Vigod S, Cobigo V. Contextual factors associated with uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening: A systematic review of the literature. Women Health 2016;56:906–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Masi CM, Blackman DJ, Peek ME. Interventions to enhance breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment among racial and ethnic minority women. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64:195S–242S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:144–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Villani J, Mortensen K. Patient-provider communication and timely receipt of preventive services. Prev Med 2013;57:658–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chou AF, Rose DE, Farmer M, Canelo I, Yano EM. Organizational factors affecting the likelihood of cancer screening among VA patients. Med Care 2015;53:1040–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Onega T, Haas JS, Bitton A, et al. Alignment of breast cancer screening guidelines, accountability metrics, and practice patterns. Am J Manag Care 2017;23:35–40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang M, Hughes DR, Appleton CM, McGinty G, Duszak R., Jr. Recent trends in adherence to continuous screening for breast cancer among Medicare beneficiaries. Prev Med 2015;73:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wernli KJ, Arao RF, Hubbard RA, et al. Change in breast cancer screening intervals since the 2009 USPSTF guideline. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:820–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]