Abstract

Improving health governance is increasingly recognised as a key pillar for achieving universal health coverage (UHC). One good practice example of a participatory health governance platform is the National Health Assembly (NHA) in Thailand. This review of 9 years of the Thai NHA process attempted to understand how it works, given the paucity of such mechanisms worldwide. In addition, an in-depth look at its strengths and weaknesses allowed for reflection on whether the lessons learnt from this participatory governance model can be relevant for other settings.

Overall, the power of stakeholder groups coming together has been impressively harnessed in the NHA process. The NHA has helped foster dialogue through understanding and respect for very differing takes on the same issue. The way in which different stakeholders discuss with each other in a real attempt at consensus thus represents a qualitatively improved policy dialogue.

Nevertheless, the biggest challenge facing the NHA is ensuring a sustainable link to decision-making and the highest political circles. Modalities are needed to make NHA resolutions high priorities for the health sector.

The NHA embodies many core features of a well-prepared deliberative process as defined in the literature (information provision, diverse views, opportunity to discuss freely) as well as key ingredients to enable the public to effectively participate (credibility, legitimacy and power). This offers important lessons for other countries for conducting similar processes. However, more research is necessary to understand how improvements in the deliberative process lead to concrete policy outcomes.

Keywords: health governance, health systems, participation, participatory governance, health policy

Summary box.

Improving participatory governance in health systems is an increasingly important area of concern for countries seeking to achieve universal health coverage, yet it is not clear how best to institutionalise multi-stakeholder governance.

Thailand’s National Health Assembly (NHA) model offers useful insights into a system which has been fine-tuned over the last decade.

The NHA has become a recognised and appreciated national public good over the last decade, and has been a key enabling factor for building civil society capacity to engage with the policy-making process, and for bringing evidence more strongly into policy discussions.

However, challenges which need to be addressed urgently are the weak link to actual policy implementation and the question of how representative NHA delegates are of their constituencies.

Working on ensuring a strong and sustainable link to decision-making and the highest political circles will make the NHA more relevant and bring in more and diverse stakeholders into the active participatory process.

The core features of a well-prepared deliberative process are represented in the NHA which may be key factors of their success: (1) provision of balanced, factual information; (2) inclusion of diverse perspectives to ensure expression of untapped viewpoints; (3) opportunity to reflect on and discuss freely a wide spectrum of perspectives.

Introduction

Improving health governance is increasingly recognised as a key pillar of universal health coverage (UHC). Greer and Méndez argue that governments who can be held accountable to their populations are more likely to ensure more inclusive health service coverage.1 Almost all published frameworks for health governance include an aspect related to a government’s ability to convene and ensure ‘participation’ or ‘population voice’ in health policy-making and decision-making.2–8 Many publications have even made active calls to governments and the international community to ‘work with citizens in designing UHC’ and be ‘responsive to public demands through participatory multi-stakeholder governance’.9 Fryatt et al 10 argue that improving governance within the context of UHC needs to be especially adapted to country contexts, with an evidence base which is as local as possible. A promising such example is the National Health Assembly (NHA) in Thailand, which has been developed over the years through local research and experimentation.

This review took place with the objective of analysing Thailand’s 9-year NHA experience, with a focus on understanding its mature process based on years of fine-tuning. We did not evaluate impact; we primarily sought to draw lessons on how to set up and maintain such a complex process. The Thai experience derives largely from health reforms introduced in the late 1990s creating a socio-political environment which was conducive to more open citizen-state engagement.11 In addition, the public increasingly demanded more participation and consultation in policy-making.12 A sufficiently long and sustained period of collective citizen consciousness was cultivated in subsequent years, culminating in the first NHA in the early 2000s. Each of the NHAs since then have served as learning experiences for both citizens and the state to improve on for the next round.

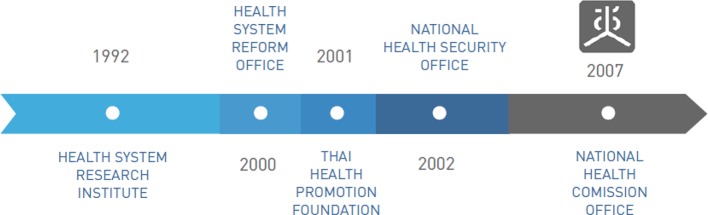

The National Health Act which passed in 2007 (figure 1) was a landmark piece of legislation which secured participation as the basic orienting principle and practice in health policy-making in Thailand. The National Health Act conceived the National Health Commission Office (NHCO) with the mandate to hold yearly assemblies. It is to be noted that the National Health Act was preceded by years of advocacy and action by government, academia and civil society for health reform and helped bring about measures such as the National Health Security Act (2002) and the Health Promotion Foundation Act (2001).

Figure 1.

National Health Act timeline.22

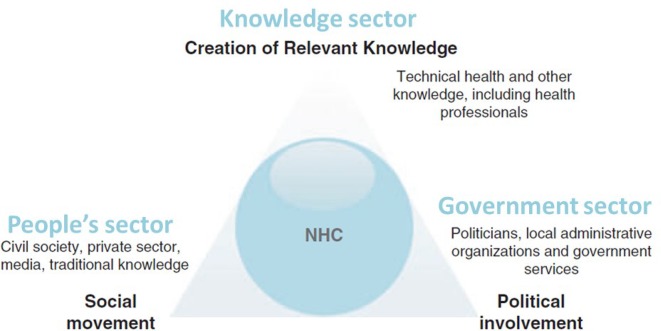

We used an analytical framework for developing a theory of change (ToC) for population/citizen’s voice activities produced by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).13 The ultimate objective of the ToC was to explore and explain the NHA as an expression of citizen-state engagement and better understand its results. Taking guidance from the ODI framework and based on both a document review of existing English-language literature on Thailand’s participatory governance processes (box 1) and several discussions within the review team, the ToC depicted in figure 2 was developed. This ‘storyline’ acknowledges the key role played by a favourable socio-political environment created by the dynamic of health reform, providing certain opportunities and noting constraints (figure 2). The ToC informed our interview and focus group guides (box 2).

Box 1. Documents reviewed in English and Thai.

Documents reviewed: English

National Health Commission Global Partnerships Unit. Thai National Health Assembly. Bangkok: National Health Commission Office; 2015.

National Health Commission Office. Birth of health assembly—Crystallization of learning towards well-being. Bangkok: National Health Commission Office; 2004.

Rasanathan K, Posayanonda T, Birmingham M, Tangcharoensathien V. Innovation and participation for healthy public policy: the first National Health Assembly in Thailand. Health Expectations. 2011;15:87–96.

Slides by Dr. Jiraporn Limpananont, 2014, ‘A Process of National Health Assembly’.

Chuengsatiansup K. Deliberative action: Civil Society and Health Systems Reform in Thailand. Bangkok: National Health Commission Office; 2008.

Bull World Health Organ. Thai public invited to help shape health policies. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:89–90.

Wasi P. ‘Triangle That Moves The Mountain’ and Health Systems Reform Movement in Thailand. Hum Res Health Dev J. 2000; 4(2).

Kanchanachitra C, Patcharanarumol W, Posayanonda T, Tangcharoensathien V. Development of Participatory Healthy Public Policies Through the Desirable National Health Assembly in Thailand (unpublished).

Documents reviewed: Thai (in English summary version)

-

Book: Looking Back and Moving Forward of Health Assembly

Author: Amphon Jindawatthana (2011).

Chapters:

Synthesizing Lesson Learned from the Health Assembly.

Toward the Better Future.

Postscript.

-

Book: The Health Assembly: philosophy, concepts and spirituality.

Author: Komatra Chuengsatiansup (2012).

Chapters:

Looking Forward: Health in Political Context and the Future of Thailand’s Health Assembly.

Figure 2.

Theory of change for Thailand’s 9 years of National Health Assembly (NHA) experience.

Box 2. Interviews and focus group discussions.

An attempt was made to ensure an approximately equal number of interviewees per triangle group (see figure 3). Besides the current and previous National Health Commission Office (NHCO) Secretary-General, three government, two academia and two civil society representatives were interviewed. Also, two focus group discussions were conducted, one with the ‘people’ National Health Assembly constituency in Chacheongsao province and another with staff of the National Economic and Social Development Board. The interviews were conducted by WHO and NHCO. They were transcribed, and where necessary, translated into English, by an external contractor. The theory of change and observatory notes from the interviews contributed to a draft coding framework which was applied on the key informant interviews and focus group transcripts. Five of the authors independently coded the transcripts; each transcript was coded by two people and cross-checked for concurrence in a 2-day workshop in April 2017. The workshop format served to validate the coding, increase inter-rater reliability, and reduce confirmation bias through discussion of various viewpoints and interpretations of the transcripts with the aim of consensus. In addition, NHCO, having the most vested interest in this topic, was not on the analysis team. Instead, WHO as a neutral party and the Paris University of Applied Sciences as a completely external party did the coding and analysis. The coding process helped identify additional major themes and confirmed those which were already in the coding framework.

How the NHA works

NHA concept and process

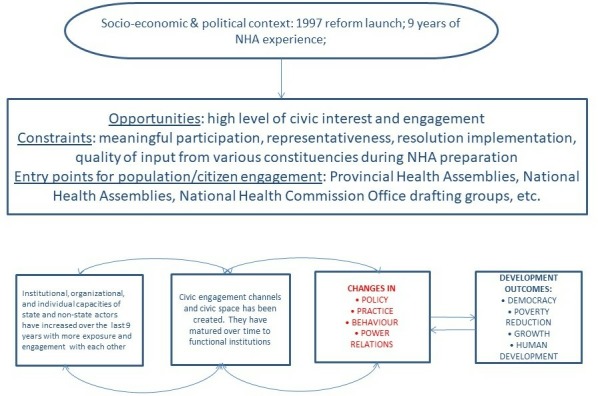

The NHA’s foundation is the concept of the ‘triangle that moves the mountain’ (figure 3). The triangle’s vertices represent: government technocrats, policy-makers and politicians; civil society, communities, and the population; and academia, think tanks, and research institutions.14 The NHA’s core principle is to bring together the triangle’s three groups to discuss critical policy issues to achieve progress and reform; a mutual understanding is thus fostered within the structured NHA process and its clear objectives. The NHA is thus meant to be a tool to put in practice public participation in policy formulation and implementation.

Figure 3.

The principle underlying the National Health Assembly: a triangle that moves the mountain.23 NHC, National Health Commission.

NHA resolutions are passed on consensus and are not binding.12 The NHA aims to achieve influence and compliance through the legitimacy its broad stakeholder base lends to its resolutions. If a consensus cannot be reached (this happens rarely), the agenda item must be deferred to allow more time for consultation. All constituencies have equal speaking rights. Varying points of view are welcomed, and every attempt is made to put all sides on equal footing (through capacity-building, awareness raising work, etc).

NHA administrative set-up

The National Health Commission (NHC), the steering body for the NHCO, was established by the National Health Act in 2007. Its official responsibility includes advising the Cabinet on policies related to health. The NHC has 39 members with the three angles of the triangle equally represented. Over 50% of the NHC’s members do not come from the health sector, attesting to the true holistic approach taken to health. Commission members are self-selected within subgroups of the triangle constituencies, either by election or nomination.

The NHCO acts as the secretariat of the NHC. Including the Secretary-General, it has a staff of 93 people (2017) including (but not only) those working specifically on developing the NHA agenda, following up on resolutions, supporting provincial health assemblies, building capacity of constituencies, monitoring and evaluating the NHA, and working on advocacy and communication for participatory policy-making.

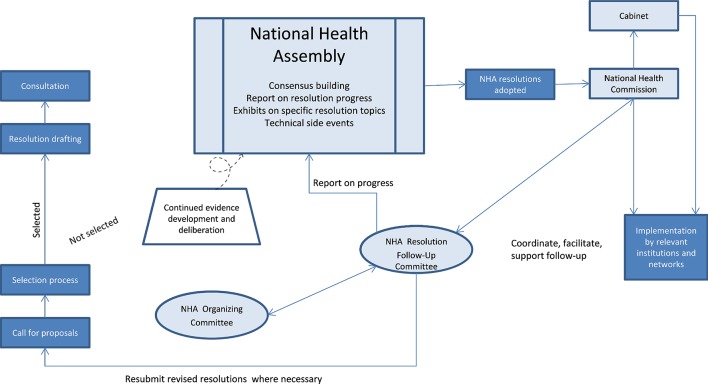

The National Health Assembly Organizing Committee (NHAOC) oversees the entire process of the NHA. The NHC appoints the President of the NHAOC, taking into consideration potential candidates’ ability to moderate discussions with opposing views. The president and the composition of the NHAOC as a whole reflect the triangle concept with diverse membership from different population groups. The NHAOC receives proposals for resolutions and jointly decides which ones will be taken forward for study within the drafting groups of the NHA (figure 4). Proposals to the NHAOC can be submitted by anyone and must show collaboration with other triangle groups. For the ninth NHA (2016), 29 proposals were received, and four were deliberated on at the NHA. The NHCO provides seed funding for the drafting groups to then develop their resolution topics further. The NHAOC keeps tab of progress on all drafting groups and oversees them.

Figure 4.

The National Health Assembly set-up and process.

Drafting groups write background papers and draft resolutions on topics selected by the NHAOC. All documents are put on the NHA website and disseminated directly to stakeholders to inform pre-NHA discussions. Public hearing forums are also held and help fine-tune the resolution. Some topics may be postponed to the next NHA if the drafting group deems the evidence insufficient or feels that more time is needed to refine the arguments and build consensus. The drafting groups are composed of those who have submitted the proposal (eg, civil society), as well as those who were consulted and requested to give input to the proposal (eg, a relevant ministry department or a research institution who might have assisted in explaining the evidence base on the topic). The drafting groups must have representation from all triangle constituencies, and many strive to include a wider range of actors or secure strong representation from specific groups based on the topic at hand. (For example, a proposal on essential medicines would explicitly target the private sector and pharmaceutical companies, but those stakeholders may be less relevant for other topics.)

Within the broad NHA ‘triangle’ groups, the NHCO defines specific constituency groups (The NHCO refers to a constituency to mean a group of people, organisations, agencies or a network who are united behind common goals and objectives and undertake joint activities consistent with those objectives.) with an assigned number of representatives. Each NHCO-defined constituency group organises its own consultation process to select its representatives for the NHA. The number of such groups increases each year according to the resolution topics addressed at the annual NHA. No group is ever removed from the list; new groups are added each year as relevant. For the NHA9, there were 280 constituency groups.

Achievements

NHA has been a useful platform for bringing together a wide range of stakeholders to discuss complex health challenges on a regular basis. It is recognised as a national public good

It was widely acknowledged in interviews that most NHA stakeholders would not normally come together otherwise and thus, the annual event provides a significant impetus to convene and jointly address matters of concern. Many stakeholders admitted that widespread scepticism prevailed when the NHA was initially launched, mainly regarding its usefulness for decision-making. However, despite lingering challenges in linking NHA to policy-making, stakeholders recognised the clear added value of the NHA process, specifically in their own work, and generally in furthering public health goals.

Particularly for more complex health problems, the NHA was used and appreciated as a vehicle for policy dialogue. For example, the NHA was the main platform used for stakeholder dialogue on issues where the health sector’s reach was limited, and multi-sectoral collaboration was required. In fact, as the former Secretary-General of NHCO, summarised succinctly: “We established the office of national health commission chaired by the prime minister, not by the ministry of public health, because we saw that that ideation of health comes from every sector”.

NHA has helped enable the ‘people’s sector’ to take on their civic duty and meaningfully engage with the policy-making process

The NHA platform was used initially by Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to bring forward issues of their interest and was primarily perceived as a platform for community complaints and concerns. Especially government interviewees characterised the NHA in its beginning years as a ‘complaint platform’ rather than a ‘solution platform’.

In the beginning, CSOs pointed fingers mainly at government, with most Ministry departments reacting defensively. Compounding this criticism was the reality that many were not in the position to change anything without support from higher government circles. Interviewees from all sides recalled the heated atmosphere of the initial meetings, describing it as a ‘battleground’. However, over time, many government officials interviewed acknowledged that civil society had learnt to organise and coordinate among themselves and had started collaborating more closely with academia. The latter point is significant as it meant that community organisations “became more mature. They don’t go and complain anymore. They come with the evidence and knowledge”.15

The emphasis on solutions has also brought community groups and civil society to acknowledge the multi-stakeholder nature of roles and responsibilities, including their own. Government key informants mentioned that the NHA process has led to civil society taking on significant roles in the implementation of resolutions, and in general, contributing actively to attaining public health goals. The people sector focus group discussion yielded the same conclusion: “If this channel [did] not exist, there is no chance for local people to propose various issues. So it is beneficial for us. Besides, it is also the development of people”.

The attention accorded to the NHA process, more than to the event itself, has allowed for a steady improvement in quality over time

Civil society interviewees expressed appreciation for NHCO’s support, provided through its 92-strong staff—support which happens mainly before the NHA event in order to ensure a well-prepared NHA. NHCO’s role includes managing health assembly stakeholders and content, building evidence and dialogue skills—all process-related efforts which were also lauded by other stakeholders (government, private sector, academics) who recognised the shift in the quality of dialogue, going from a more confrontational to a solution-oriented consensus mode where decisions can be taken.

NHA is a key vehicle for bringing evidence more strongly into policy discussions

Structured dialogue needs material for discussion, increasing the demand for evidence. The NHA as a platform for structured dialogue thus gives equal emphasis to the knowledge sector in its tripartite governance structure, thereby explicitly putting emphasis on evidence. The NHA’s added value is that it combines both the evidence analysis and the deliberation around the evidence, both at the topic proposal stage and when feasibility of solutions is discussed.

If the topic-specific working group is unable to establish sufficient evidence, the proposal is tabled until the following NHA. This system favours proposals which demonstrate a clear evidence base on their topic and offer feasible policy options. Before even advocating for a topic area, civil society is incentivised to collaborate with academia to examine the evidence both on the effect of the health or policy problem as well as on practical and implementable solutions.

Challenges

Integration of resolutions into health policies remains a key challenge

Implementation of resolutions is perceived as poor and too slow across the different stakeholders interviewed. Resolutions reflect the consensus of the NHA’s broad stakeholder base which is supposed to bring legitimacy when deliberated on in policy circles.16 However, resolutions are not always systematically taken up for action (they are not binding), with political will determining which policy topics to address. Internal policy-making processes are still given priority and it is unfortunately not well integrated with the NHA process. One civil society informant deplored, “the government sector … it is impossible … to command them or order them. Sometimes you have to beg them to do according to the resolution. It is very hard to do like that”.

Civil society informants also observed that government participation is not at a high enough level for decisions to be taken based on resolutions. They noted that operational-level government cadres are active in the NHA process but felt that decision-makers with more influence needed to be present to ensure high-level backing of resolutions.

Increased capacity and coordination skills are necessary within constituencies to select the right representatives

The quality of representation is at the crux of the quality of the NHA. Different population groups are in theory supposed to come to the Assembly with a constituency-wide coordinated viewpoint, although this is not always the case. A community focus group participant complained accordingly, “These representatives must bring the opinion of the group that they are representing, not just their own opinion”.

The quality of representation is influenced heavily by the capacity of the constituency in the NHA system of self-selection. It was observed by many government interviewees that high-capacity constituencies do better representative selection and have a stronger voice. One government focus group participant complained that the same skilled, high-capacity, well-resourced civil society representatives were at the NHA, and in the committees and subcommittees, each year. A key informant summed it up by saying “Besides, the National Assembly is half closed. That is, we are accustomed to most participants … Currently, approximately 50% of the participants we meet are the [already] existing [ones ]”.

Those with lower education levels and less free time on their hands were only heard if their local CSO networks were able enough to reach out to them and pro-actively bring in their voice. There still remain many provinces and topic areas where the poor, vulnerable and marginalised are not heard enough, and where careful outreach work would benefit both these groups and the NHA process overall. A well-reflected analysis of who are not participating, and why, would form a sound basis for designing this outreach work. In addition, one key informant suggested targeted focus groups for low-income, less educated, marginalised and vulnerable groups; the results of these targeted focus group discussions would feed into the drafting group deliberations. The idea is to put these less advantaged groups in an atmosphere where they might feel more at ease to express themselves in their own language. Currently, the working groups tend to be dominated by technical jargon, often leaving less articulate members feeling daunted and silenced.

LESSONS FOR OTHER COUNTRIES

Blacksher et al 17 describe core features of a well-prepared deliberative process as: (1) provision of balanced, factual information; (2) inclusion of diverse perspectives to ensure expression of untapped viewpoints; (3) opportunity to reflect on and discuss freely a wide spectrum of perspectives. These elements seem to all be in place in Thailand which may have contributed to its relative success in terms of process.

Regarding information provision, the emphasis on evidence existed from the beginning with the triangle vertex ‘knowledge sector’. The NHA process has encouraged civil society and the research community to join forces; government institutions have followed suit, realising that evidence clearly help legitimise policies. The NHA has thus pushed health policy-making into a more evidence-led sphere. Regarding inclusivity, the NHCO’s civil society capacity-building strategy has paid off, with more civil society-academia collaboration, and improved internal constituency coordination. The former has led to more meaningful input by those who would not participate otherwise, as the NHA process nudges stakeholders to think through solutions, rather than focusing solely on the problems themselves.

Vastly improved internal coordination among community groups and civil society is also a side effect of the NHA process, tangibly improving inclusivity. The NHA essentially helped reinforce, and in many places, create, a tight network of citizens and community members with a stake in the same topic, and forced those diverse viewpoints to converge into a common stance to be expressed jointly at the NHA. Regarding the opportunity to discuss freely, the NHA platform provides it not only during the 3-day Assembly but during a full year-long deliberation process which interviewed stakeholders clearly perceived as a national public good. The opportunity to reflect freely is thus multiplied through a series of encounters between various stakeholders who would not have come together otherwise.

However, despite a fairly exemplary process and good political commitment, the policy link of the NHA is weak. Abelson et al 18 mapping of public deliberation activities found that policy impact documentation is in its infancy due to the complexity of the topic and needs further conceptualisation. In general, the literature points rather to ‘soft’ results such as changes in institutional culture, greater trust and openness, increased diversity of actors, and a more explicit underpinning of policy options in articulated social values.19 20 More research is needed to understand how these soft results lead to responsive policy-making and implementation. A follow-up study in Thailand specifically examining NHA impact would be a good starting point.

Based on a trial process evaluation study, Boivin et al 21 propose three key ingredients for effective participation on the side of the public: credibility, legitimacy and power. Applying this to the Thai NHA, credibility was established through collaboration with evidence generators, access to experts and information, in addition to their personal experience as affected parties. Boivin demonstrate that legitimacy can be fostered by ‘the recruitment of a balanced group of participants and by the public members’ opportunities to draw from one another’s experience’. The NHA model’s capacity-building component for representative self-selection among a constituency reflects this approach exactly. The capacity-building attempts to ensure a balanced group of participants; the self-selection process means that the constituency must dialogue and find consensus among members by drawing on each other’s’ experience. Boivin argue that with credibility and legitimacy, power relations become equalised between the public and other stakeholders.

Conclusion

The NHA institution has helped improve civic consciousness and amplify citizen’s voice. Significantly, it has also led to a tacit acknowledgement by many government actors that they are not the sole owners of the solutions to Thai health sector challenges. This is relevant as it acknowledges a more modern paradigm of the Ministry of Health’s role in a world where populations demand greater access and input into how their health is shaped. The improved quality of dialogue and consultations linked to shifts in mind-set of officials and citizens over time has led to an increased understanding and respect for each other’s views and a more balanced perspective reflected in consensus-based resolutions. The chain of results such as these considered ‘soft’ towards real policy change is unclear in Thailand. A more reflected, concerted effort is needed to lobby for a greater link between internal government policy processes and the NHA. This effort could be underpinned by a targeted NHA impact study, which would also add to the global body of evidence on policy impact documentation which is currently paltry.

Acknowledgments

This paper was drawn from research done within the remit of WHO’s work stream on participatory health governance which aims to give guidance to Member States on how to engage most effectively with populations, civil society, and communities for health policy-making. The full case study report on Thailand can be found here: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260464.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: DR conceptualised the study, collected data, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. NM, WP, TP and PP helped collect data and contributed to the manuscript. SdC, RB, ER, AD analysed the data and contributed to the manuscript. GS significantly revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This is part of WHO's programmatic work which is exempt from ERB approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Greer SL, Méndez CA. Universal health coverage: a political struggle and governance challenge. Am J Public Health 2015;105 Suppl 5:S637–S639. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbazza E, Tello JE. A review of health governance: definitions, dimensions and tools to govern. Health Policy 2014;116:1–11. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siddiqi S, Masud TI, Nishtar S, et al. Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing countries: gateway to good governance. Health Policy 2009;90:13–25. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baez-Camargo C, Jacobs E. A framework to assess governance of health systems in low income countries. Basel: Basel Institute on Governance, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brinkerhoff D, Bossert T. Health governance: concepts, experience, and programming options. Washington DC: USAID, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kickbusch I, Gleicher D. Governance for health in the 21st century. Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mikkelsen-Lopez I, Wyss K, de Savigny D. An approach to addressing governance from a health system framework perspective. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2011;11:13–24. 10.1186/1472-698X-11-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. USAID The health system assessment approach: a how-to manual. version 2 Washington DC: USAID, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bump J, Cashin C, Chalkidou K, et al. Implementing pro-poor universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e14–16. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fryatt R, Bennett S, Soucat A. Health sector governance: should we be investing more? BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000343 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tangcharoensathien V. The Kingdom of Thailand health system review. New Delhi: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rajan D, Mathurapote N, Puttasri W. The triangle that moves the mountain: nine years of Thailand’s National Health Assembly (2008-2016). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tembo F. Citizen voice and state accountability: towards theories of change that embrace contextual dynamics. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Limpananont J. A process of national health assembly. presentation. Geneva; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quote from a government key informant.

- 16. National Health Commission Office Thai National health assembly, health in all policies for health equity. Bangkok: National Health Commission Office, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blacksher E, Diebel A, Forest PG. What is public deliberation? Hastings center report 42, no. 2. Garrison: Hastings Center; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abelson J, Blacksher EA, KK L, et al. Public deliberation in health Policyand bioethics: mapping an emerging, interdisciplinary field. Journal of Public Deliberation 2013;9. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones M, Einsiedel E. Institutional policy learning and public consultation: the Canadian xenotransplantation experience. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:655–62. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Einsiedel EF, Ross H. Animal spare parts? A Canadian public consultation on xenotransplantation. Sci Eng Ethics 2002;8:579–91. 10.1007/s11948-002-0010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Burgers J, et al. What are the key ingredients for effective public involvement in health care improvement and policy decisions? A randomized trial process evaluation. Milbank Q 2014;92:319–50. 10.1111/1468-0009.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diagram curtesy of national health Commission office.

- 23. Rasanathan K, Posayanonda T, Birmingham M, et al. Innovation and participation for healthy public policy: the first National health assembly in Thailand. Health Expect 2012;15:87–96. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00656.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]