Abstract

Background

Pharmaceuticals are important interventions that could improve people's health. Pharmaceutical pricing and purchasing policies are used as cost‐containment measures to determine or affect the prices that are paid for drugs. Internal reference pricing establishes a benchmark or reference price within a country which is the maximum level of reimbursement for a group of drugs. Other policies include price controls, maximum prices, index pricing, price negotiations and volume‐based pricing.

Objectives

To determine the effects of pharmaceutical pricing and purchasing policies on health outcomes, healthcare utilisation, drug expenditures and drug use.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), part of The Cochrane Library (including the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Register) (searched 22/10/2012); MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and MEDLINE, Ovid (searched 22/10/2012); EconLit, ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012); PAIS International, ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012); World Wide Political Science Abstracts, ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012); INRUD Bibliography (searched 22/10/2012); Embase, Ovid (searched 14/12/2010); NHSEED, part of The Cochrane Library (searched 08/12/2010); LILACS, VHL (searched 14/12/2010); International Political Science Abstracts (IPSA), Ebsco (searched (17/12/2010); OpenSIGLE (searched 21/12/10); WHOLIS, WHO (searched 17/12/2010); World Bank (Documents and Reports) (searched 21/12/2010); Jolis (searched 09/10/2011); Global Jolis (searched 09/10/2011) ; OECD (searched 30/08/2005); OECD iLibrary (searched 30/08/2005); World Bank eLibrary (searched 21/12/2010); WHO ‐ The Essential Drugs and Medicines web site (browsed 21/12/2010).

Selection criteria

Policies in this review were defined as laws; rules; financial and administrative orders made by governments, non‐government organisations or private insurers. To be included a study had to include an objective measure of at least one of the following outcomes: drug use, healthcare utilisation and health outcomes or costs (expenditures); the study had to be a randomised trial, non‐randomised trial, interrupted time series (ITS), repeated measures (RM) study or a controlled before‐after study of a pharmaceutical pricing or purchasing policy for a large jurisdiction or system of care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. Results were summarised in tables. There were too few comparisons with similar outcomes across studies to allow for meta‐analysis or meaningful exploration of heterogeneity.

Main results

We included 18 studies (seven identified in the update): 17 of reference pricing, one of which also assessed maximum prices, and one of index pricing. None of the studies were trials. All included studies used ITS or RM analyses. The quality of the evidence was low or very low for all outcomes. Three reference pricing studies reported cumulative drug expenditures at one year after the transition period. Two studies reported the median relative insurer's cumulative expenditures, on both reference drugs and cost share drugs, of ‐18%, ranging from ‐36% to 3%. The third study reported relative insurer's cumulative expenditures on total market of ‐1.5%. Four reference pricing studies reported median relative insurer's expenditures on both reference drugs and cost share drugs of ‐10%, ranging from ‐53% to 4% at one year after the transition period. Four reference pricing studies reported a median relative change of 15% in reference drugs prescriptions at one year (range ‐14% to 166%). Three reference pricing studies reported a median relative change of ‐39% in cost share drugs prescriptions at one year (range ‐87% to ‐17%). One study of index pricing reported a relative change of 55% (95% CI 11% to 98%) in the use of generic drugs and ‐43% relative change (95% CI ‐67% to ‐18%) in brand drugs at six months after the transition period. The same study reported a price change of ‐5.3% and ‐1.1% for generic and brand drugs respectively six months after the start of the policy. One study of maximum prices reported a relative change in monthly sales volume of all statins of 21% (95% CI 19% to 24%) after one year of the introduction of this policy. Four studies reported effects on mortality and healthcare utilisation, however they were excluded because of study design limitations.

Authors' conclusions

The majority of the studies of pricing and purchasing policies that met our inclusion criteria evaluated reference pricing. We found that internal reference pricing may reduce expenditures in the short term by shifting drug use from cost share drugs to reference drugs. Reference pricing may reduce related expenditures with effects on reference drugs but the effect on expenditures of cost share drugs is uncertain. Reference pricing may increase the use of reference drugs and may reduce the use of cost share drugs. The analysis and reporting of the effects on patients' drug expenditures were limited in the included studies and administration costs were not reported. Reference pricing effects on health are uncertain due to lack of evidence. The effects of other purchasing and pricing policies are until now uncertain due to sparse evidence. However, index pricing may reduce the use of brand drugs, increase the use of generic drugs, and may also slightly reduce the price of the generic drug when compared with no intervention.

Plain language summary

The effect of pricing policies for pharmaceuticals

Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a review of the effect of reference pricing and other pricing policies for pharmaceuticals. In 2012, they searched for all relevant studies and finally included 18 studies. Their findings are summarised below.

What are reference pricing and other pricing policies for pharmaceuticals?

Large amounts of healthcare funds are spent on medicines and these amounts are increasing. Spending more on medicines could mean less money for other healthcare or non‐health care services. Health insurers are therefore looking for ways of controlling the costs of medicines while still ensuring that patients get the medicines they need.

One approach that health insurers can use is reference pricing. Here insurers group together medicines that have the same active ingredients or that are used for the same purpose and are just as effective and safe. They then set a 'reference price' that they are willing to pay. If the patient chooses the 'reference medicine', his expenses will be paid. If he chooses a more expensive medicine he will have to pay the difference.

Another approach is index pricing. Again, insurers group together similar medicines. They then set an 'index price' that they refund to pharmacies each time they dispense a medicine from this group. As the pharmacy is refunded the same amount for any of the medicines in this group it is in their interest to dispense a medicine that costs less than the index price.

A number of other pricing policies also exist that aim to control medicine costs. It is assumed that these types of policies can lead patients to switch to cheaper medicines and can encourage medicine producers to lower their prices.

What happens when new payment policies are introduced?

Most of the studies focused on the effect of reference pricing. These studies looked at the impact of reference pricing one year after it was introduced. They showed that this policy may lead to:

‐ an increase in 'reference medicine' prescriptions and a decrease in prescriptions for more expensive medicines (low certainty of evidence);

‐ a decrease in the amount of money insurers spend on medicines overall (low certainty of evidence).

None of these studies looked at the effect of reference pricing on people’s health, their use of healthcare services, or adverse effects.

A summary of this review for policy‐makers is availablehere

Summary of findings

Background

See Additional Table 5 for a list of abbreviations used in this review.

1. Abbreviations.

| Abbreviations | Complete name |

| ACE | Angiotensin converting enzyme |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive integrated moving average |

| CBA | Controlled before and after |

| CCB | Dihydropyridine channel blocker |

| CRM | Controlled repeated measures |

| EPOC | Effective Practice and Organisation of Care |

| H2RA | Histamine‐2 receptor antagonist |

| INN | International non‐proprietary name |

| ITS | Interrupted time series |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development |

| PPI | Proton pump inhibitors |

| PPRS | Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| RM | Repeated measures |

| ROR | Rate of return |

| RP | Reference pricing |

| RR | Risk ratio (intervention vs control group) |

| RR (adj) | Risk ratio (adjusted for pre‐intervention differences) = RR post‐intervention/RR pre‐intervention |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Description of the condition

Pharmaceuticals can be important for people's health. At the same time drugs are major components of healthcare costs. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) countries spent USD 569 billion on pharmaceuticals (excluding pharmaceuticals for in‐patients) in 2005; US pharmaceutical expenditure amounted to USD 235 billion, accounting for 41% of total expenditure on pharmaceuticals in OECD countries (OECD 2008). Pharmaceutical expenditure in Mexico represents 21% of total health spending, exceeding the average of OECD countries; and in 2003 88% of pharmaceutical expenditure in Mexico was out of pocket expenditure (Moïse 2008).

Data on total pharmaceutical expenditure for 2006 confirm that pharmaceuticals account for an important share of all expenditure on health. This proportion varies considerably between high‐ and low‐income countries; pharmaceutical spending as a share of total health expenditure ranges from a mean of 19.7% in the high‐income countries to a mean of 30.4% in the low‐income countries (WHO 2011). Per capita pharmaceutical expenditures in 2005 and 2006 ranged from USD 7.61 in low‐income countries to USD 431.6 in high‐income countries and, compared to 1995, the rate of increase is greater in middle‐ and low‐income countries (WHO 2011). These increases put pressure on policy makers and insurers to control drug expenditure and to do this without causing adverse effects on health or increasing healthcare utilisation or other costs.

Description of the intervention

Pharmaceutical pricing and purchasing policies intend to determine or affect the prices that are paid for drugs. They can be targeted at different components of drug prices, such as wholesale prices, retail prices, drug taxes and reimbursement prices. Examples are price controls, maximum prices, price negotiations, reference pricing, index pricing and volume‐based pricing policies. Although this review also deals with purchasing policies, for simplicity we will use the term pricing policies (Table 6).

2. Intervention description.

| STUDY ID / INTERVENTION PERIOD IN STUDY | DRUGS INCLUDED IN ANALYSIS | INTENSITY AND INCENTIVES | EXEMPTIONS |

| POLICY: REFERENCE PRICING | |||

|

Aronsson 2001 1993‐1996 |

12 different brand drugs: cimetidine, furosemide, atenolol, pindolol, propranolol, indomethacin, naproxen, allopurinol, paracetamol/codeine, diazepam, clomipramine, timolol | Reference price: 10% above the price of the least expensive generic substitute | No information provided |

|

Brekke 2011 2003 |

Drugs included in the analysis: brand‐names and generics and pharmaceutical expenditures | Under a reference pricing (RP) system, firms are free to set drug prices, but patient copayment is based on a RP, that is set by a regulator.More specifically, if a consumer chooses a drug that is priced higher than the RP, she has to pay the full difference between the RP and the actual drug price. Usually, the RP is set at a level somewhere between the lowest and highest drug price in the market. | No information provided |

|

Grootendorst 2002 For nitrates: October/November 1995 to May 1999 (March 1998 for some outcomes). For ACE inhibitors and CCBs: January 1997 to March 1998 |

Nitrates (used for stable angina) for long term prophylaxis, ACE inhibitors (used for hypertension, congestive heart failure and diabetic nephropathy) and dihydropyridine CCBs (used for hypertension and stable angina) | Reference price: Nitrates: Price of lowest priced regular‐release ISDN. ACE inhibitors and dihydropyridine CCBs: A fixed cost per 30 day supply. Incentives for physicians to prescribe lower dosages to not exceed monthly cap. Costs for the least‐expensive captopril, quinapril, and ramipril preparations available in pharmacies were covered. For other ACE inhibitors (enalapril, lisinopril, fosinopril, cilazapril, benazepril) patients were required to pay the difference, ranging from 2 to 62 Canadian Dollars per monthly supply. Reference prices in Canadian Dollar per 30 day supply were about 11 for H2RAs, 31 for dCCBs, 4 for nitrates and 27 for ACE inhibitors. Price year not reported. | Special authority exemptions*: Nitrates, ACE inhibitors, CCBs. Therapeutic trial exemptions**: ACE inhibitors, CCBs. Automatic exemptions: Users of asthma or diabetes drugs: ACE inhibitors, CCBs. Residents of long term facilities: Nitrates. Prescriptions dispensed by specific specialists: CCBs, Nitrates. Some transdermal nitroglycerin patches were exempted from the reference pricing from January 1996 and March 1996. Suffciently low doses (not exceeding reference price for 30 day supply) were exempted from the reference pricing: ACE inhibitors, CCBS, nitrates (after September 1, 1998). |

|

Grootendorst 2005 Pharmacare introduced two different forms of RP to the NSAIDs, Type 1 in April 1994 and Type 2 in November 1995 |

Drug class NSAIDs | Under the policy, the less costly 'unrestricted' NSAIDs, enteric‐coated acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (650 mg), ibuprofen, and naproxen remained fully reimbursed (at an average rate of about $0.23 daily). Pharmacare also began to reimburse acetaminophen (500 mg). The decision to provide full reimbursement for acetaminophen, ASA, ibuprofen, and naproxen was consistent with earlier recommendations by an independent academic research group, the BC Therapeutics Initiative, that these drugs be used as first line therapy for osteoarthritis (Therapeutics Initiative 1995). | Patients intolerant of unrestricted NSAIDS or with specific diagnoses (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, collagen vascular disease, or gout) were eligible for exemption from the policy. Exemption for a ‘‘second line restricted’’ NSAID (nabumetone, piroxicam, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, to‐ lmetin, sulindac, ketorolac, or diclofenac potassium) required failure on a first line restricted NSAID. |

|

Grootendorst 2006 Jan 1994 to December 2000 |

ACE inhibitors and CCBs | Reference pricing (RP) limits drug plan reimbursement of interchangeable medicines to a reference price, which is typically equal to the price of the lowest‐cost interchangeable drug. | Under the RP policy, Pharmacare reimbursement of the ACE inhibitors enalapril, lisinopril, fosinopril, cilazapril, and benazepril was limited to $27 per month; the lower‐cost ACE inhibitors, captopril, quinapril, and ramipril remained fully reimbursed. Reimbursement of the dihydropyridine CCBs nifedipine, nicardipine and amlodipine was limited to $31 per month; felodipine remained fully reimbursed. Also, reimbursement of the sustained release forms of the CCBs diltiazem and verapamil was limited to the price of regular release versions of the equivalent dosage sizes of the same drugs. Beneficiaries who required a higher‐cost anti‐ hypertensive for medical reasons could be exempted from RP upon written petition by the physician. |

|

Hazlet 2002 October 1995 to March 1996 |

Histamine2 receptor antagonists | Reference prices per 30 day supply were about 11 Canadian dollars for H2RAs (See Grootendorst 2002), lowest priced H2RA available. Special authority restrictions for reimbursement of PPIs, made H2RAs more attractive. | Special authority exemptions*. Exemptions for low doses |

|

Kibicho 2012 2003 |

1. Antihypertensive drugs 2. Antihyperlipidemic drugs 3. Generic drugs 4. Brand‐name drugs |

The maximum allowable cost is a ceiling price set for generic and multisource brands that are chemically equivalent and have the same active ingredients (generic substitutes). Maximum allowable cost is similar to reference pricing used in Canada, which extends the concept of drug interchangeability to include chemically related active ingredients that are pharmacologically equivalent (therapeutic substitutes).Instituting maximum allowable cost is the only policy designed to directly reduce the cost of generic drugs by limiting the amount that Medicaid can reimburse pharmacies. | No information provided |

|

Marshall 2002 October 1995 to May 1999 |

Histamine2 receptor antagonists | See Hazlet 2002 | See Hazlet 2002 |

| McManus 2001 June 1997 to December 1997 | Ranitidine | The policy operated where there was more than one brand of a drug available through the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme and where the brands where therapeutically interchangeable. Generic substitution allowed. Premium on original brand Ranitidine 150 mg and 300 mg: $0,71 in May 1997. Price year not reported. | No information provided |

|

Moreno‐Torres 2011 December 2000 |

This system was applied to products with the same active ingredient, pharmaceutical form, dosage and number of units for which there was at least one generic | For each group, a reference price was calculated as the weighted average selling price of the cheapest drug accounting for at least 20% of the market. This system established the maximum price that could be reimbursed by the NHS for any version of the same drug. | No information provided |

|

Narine 2001 October 1995 to November 1996 |

Histamine2 receptor antagonists | See Hazlet 2002 | See Hazlet 2002 |

|

Pavcnik 2002 Oral antidiabetics: The first batch of reference pricing: 1989 to 1996 The second batch of reference pricing: 1994 to 1996 Anti‐ulcer drugs 1992 to 1996 |

Oral antidiabetics and anti‐ulcer drugs | No information provided | No information provided |

|

Puig 2007 January 2001 to October 2004 |

Oral HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors (statins): atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin and cerivastatin | Reference pricing (RP) is a reimbursement policy that sets a maximum allowable cost that will be covered,RP systems can be grouped into different levels according to drug interchangeability. In September 2001 the Andalusian Public Health Service (henceforth APHS) introduced a new pharmaceutical procurement mechanism based on a more “intensive” RP system, including maximum prices. The previous situation was characterized by the absence of incentives to prescribe lower‐cost drugs with the same active ingredient, and by the absence of incentives for brand firms to lower prices even in the presence of lower‐priced generics. Seasonal fluctuations were controlled by including a term for August in the regression model. Seasonal variation is observed in the monthly periods resulting in a significant decrease during summer holidays (August). |

No information provided |

|

Sawyer 1983 September 1976 to October 1979 |

52 dosage forms of 25 multisource chemical entities, including ampicillin, chlordiazepoxide HCL(Librium), penicillin VK, propoxyphene HCL (Darvon) and tetracykline | State of Maryland used Maximum Allowable Costs ‐ Estimated Acquisition Costs (MAC‐EAC) procedures to reimburse community pharmacists for outpatient drugs dispensed to Medicaid patients. Maryland pharmacies billed Medicaid their usual and customary charges to the general public. Medicaid officials then determined the allowable cost for each claim by comparing billed charges against the appropriate MAC and/or EAC limits. Pharmacies were reimbursed the lowest established level (+ the flat dispensing fee). | No information provided |

| Schneeweiss 2002 January 1997 ‐ April 1998 (for the outcome drug use) | ACE inhibitors | See Grootendorst 2002 | See Grootendorst 2002 |

| Schneeweiss 2003 January 1997 to April 1998 | CCBs | See Grootendorst 2002 | See Grootendorst 2002 |

|

Stargardt 2010 January 2003 to December 2006 |

Atorvastatin and other statins | Reference pricing has been the subject of great debate since its introduction in Germany in 1989, the inclusion of statins was on 1 January 2005. Atorvastatin was classified as a ‘‘me‐too’’ drug and grouped with other statins, including generics. Additional co‐payments due to reference pricing for atorvastatin ranged from € 18.17 per package (30 mg/30 units) to € 109.00 per package (80 mg/100 units). As a result, pre‐ policy users of atorvastatin had to decide whether to switch to another statin to avoid additional co‐payments or to pay the difference between the price of atorvastatin and its reference pricing. |

In contrast to reference pricing in British Columbia, the German reference pricing system does not allow requests for exemption on a case‐by‐case basis, nor does it allow specific subgroups of patients to be excluded from the scheme |

| POLICY: INDEX PRICING | |||

|

Brekke 2003 1998‐2003 |

Six groups of active substances: cetirizin (treatment of allergy), citalopram (antidepressant), enalapril (antihypertensive), lisinopril (antidepressant), loratadin (treatment of allergy) and omeprazol (treatment of gastro‐intestinal disorders) | The levels of index prices relative to the prices of substitute drugs were not reported by the authors. | When prescribing physician proscribes substitution of a generic in pharmacies |

| POLICY: MAXIMUM PRICES | |||

|

Puig 2007 2004 |

Oral HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors (statins): atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin and cerivastatin | In September 2001 the Andalusian Public Health Service (henceforth APHS) introduced a new pharmaceutical procurement mechanism based on a more “intensive” RP system, including maximum prices. In the APHS the reference price level is set at the level of the higher price of the two lowest‐priced products for each active ingredient with the same package size and dose strength. This system only works when and if physicians prescribe the active ingredient of the product. The pharmacies agreed with the regional government to dispense the lowest‐priced product for each active ingredient, independently of its generic status. In addition, economic incentives were introduced for physicians to prescribe using the non‐commercial name of the active ingredient. | No information reported |

* Pharmacare may give special authority exemptions, based on therapeutic reasons provided by the physician in an application. Special authority exemptions were valid indefinitely for ACE inhibitors, CCBs and nitrates (after January 21, 1997) users. See Grootendorst 2002.

** The physicians may apply for therapeutic trial exemptions in cases of intolerance or treatment failure or if the patient is frail. See Grootendorst 2002.

*** In British Columbia Pharmacare covers all prescription drug costs for seniors with a dispensing deductible fee of CAD 200. Others can obtain similar coverage, but must pay a monthly.

These policies can have an impact on drug expenditure in two main ways, directly through price changes, and indirectly through drug use changes related to the price changes. Furthermore, the split between third party and patient expenditure can be influenced. Since pharmaceutical pricing policies might affect drug use they could also have effects on health and utilisation of other healthcare services.

Pharmaceutical prices consist of different components reflecting who is receiving the payments: the manufacturers' prices, wholesalers' prices and retailers' prices. At each of these steps there are mark ups and possibly tax components. Pricing policies can be targeted at one or more of these specific components.

In most European Union countries pharmaceutical prices are controlled at the manufacturer level and by statutory pricing policy, where the authorities set the price on a regulatory basis. Most of the countries that are members of the Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information Project (PPRI) apply price control only to pharmaceuticals that are eligible for reimbursement (Vogler 2008). This is not the case for recent pharmaceutical pricing policies applied in Latin American countries, such as Colombia (Vacca 2011). Pharmacy margins are regulated in most European Union countries by regressive schemes in which pharmacy remuneration occurs via a fixed fee (Vogler 2008).

Reference drug pricing

Reference prices can be established based on external prices (from other countries) or internal prices (within a country). Using the price(s) of a medicine in one or several countries to derive a benchmark or reference price for the purpose of setting or negotiating the price of medicines in a given country is described as external price referencing by the Worlg Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies Glossary (PHIS 2011). Using the price(s) of identical medicines (ATC 5 level) or similar medicines (ATC 4 level) or therapeutically equivalent treatments within a country to derive a benchmark or reference price for the purpose of setting or negotiating the price or reimbursement of medicines in a given country is described as internal price referencing by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies Glossary (PHIS 2011). Different terms have been used for reference drug pricing policies, including reference pricing, reference‐based pricing, maximum allowable costs, best available prices, and minimum pricing.

For reimbursement purposes the internal reference pricing makes patients aware of price differences by giving them the responsibility to pay for the difference. However, it does not restrict the drug producers', wholesalers' or retailers' freedom to set drug prices. The policy sets the reimbursement price and thus implicitly the payments by patients. This can lead patients to switch from more expensive to cheaper drugs, and thus decrease the sales for the producers of the more expensive drugs. The producers would then have incentives to reduce prices so that market shares would not be lost. Drugs that are assessed as therapeutically similar (here called a reference drug group) a reference drug (or a group of reference drugs) is chosen. The price of the reference drug is reimbursed (except for ordinary copayment). For drugs that are more expensive than the reference drug, the patient has to pay the expenses above the reference price. These are called cost share drugs. Policies that set reimbursement prices, like some reference pricing policies, are similar to copayment policies since both influence what the third party payer and patients pay for the drugs. The difference is that patients can choose to use the reference drug and thus not have to pay a reference premium, whereas with copayments patients have to pay a portion of the cost regardless of which drug they use within a drug group (Austvoll‐Dahlgren 2008).

Reference drug pricing can be applied to different levels of drug groups (Dickson 1998; Galizzi 2011; Ioannides‐Demos 2002; McLaughin 1997). At the highest level therapeutic groups are included, as all drugs used to treat a particular condition (for example all drugs for hypertension) or drugs included in the same Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system group (for example statins, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors). At a more specific level competitors' drugs for International Nonproprietary Names (INN) are included, as used in Germany, Australia and US. These drugs could be considered as chemically equivalent drugs or multisource chemical entities, or could also be classified as brand name drugs and generic drugs.

Index pricing

An index price is the maximum refundable price to pharmacies for drugs within an index group (Brekke 2003). An index group consists of therapeutically interchangeable drugs. The index price is updated quite frequently (for example every third month) and is based on the volume weighted average of prices in the index group. The price is refunded independently of which drug is dispensed. Since the pharmacy keeps the difference between the index price and the price of any drug in the index group, pharmacies have economic incentives to dispense a drug that is priced lower than the index price. Thus, the hypothesis is that the pharmacies will dispense more of the cheaper drugs, which will lead to a lower index price when that price is adjusted, which occurs frequently. A lower index price will then lead to lower reimbursements and thus reduced third party drug expenditures. An increase in the dispensing of cheaper drugs could also increase the producers' incentives to lower the drug prices so that their market shares will not decrease.

Maximum prices

Maximum or ceiling price is a fixed price that attempts to secure pharmaceutical prices that are considered ‘reasonable’ for a given health system. There are different approaches to set the maximum prices: negotiated prices, price‐caps, cost‐plus, price comparisons to other countries or to similar products within the same country, or price‐volume trade‐offs (Mossialos 2004). This is a cost‐containment measure that fixes ex‐ante the maximum price of medicines, for example taking into consideration inflation rates and production cost. Companies are allowed to choose any price below this threshold, described as price cap or price ceiling by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies Glossary (PHIS 2011).

Profit regulation

Rates of return on pharmaceutical companies' capital can be regulated by the government or negotiated between the government and the companies, as under the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) in the UK (Borrell 1999). This can indirectly influence drug prices by setting profit limits. The PPRS is based on periodic negotiations between the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry and the Department of Health. It is reviewed every few years (PPRS 2009). If profits exceed a certain level, the company must reduce profits by cutting prices, delaying or restricting previously agreed future price increases, or repaying the excess profit to the Department of Health.

Stepped price model

Prices can be adjusted when patents expire (Norwegian Pharmacy Association 2008). For example, in Norway a stepped price model was introduced in January 2005. In this model a maximum reimbursement price is set for affected drugs (both branded and generics). The maximum price is automatically reduced in steps following generic competition after patent expiry. The size of the price cut steps depends on the sales volumes prior to establishment of generic competition and the time since competition was established (Festoy 2008).

Other pricing policies

These include direct price controls, price negotiations, volume‐based pricing, procurement and rebate policies. Direct price controls involve setting prices on a product by product basis. The prices can be set by the authorities or negotiated with the manufacturer. The price level can be fixed or a maximum price can be set, leaving the supplier free to set the price lower or equal to the maximum price. When setting or negotiating the price, several considerations can be taken into account: costs of products, prices in comparable countries, therapeutic value of the product, evidence of clinical effectiveness and safety, and price‐volume arrangements (Productivity 2001).

Under a price‐volume arrangement the agreed drug price is based on a forecast volume of sales. If the actual volume exceeds the forecast, the drug price usually has to be lowered. Pricing regulation may apply to initial or posterior prices once products are marketed, and can be based on prices for the same product in other countries or on the costs of similar treatments for the same indication (Espin 2007).

Reimbursement decisions and pricing for new drugs can also be based on economic evaluations of the new treatment compared with existing options (Espin 2007).

Each of these interventions could generate important potential adverse effects or unintended effects that should be addressed.

Why it is important to do this review

Recently Galizzi 2011 provided an updated survey of original scientific studies on the effect of reference pricing policies in OECD countries, including results from searches of the PubMed database from 1966 to September 2009, EconLit and Web of Knowledge from 1979 to September 2009. This survey of the literature included theoretical and empirical studies.

There are recent reviews on some pricing policies, like reference pricing (Danzon 2008; Puig‐Junoy 2010), and systematic reviews of pharmaceutical policies that include some pricing policies (Faden 2011; Puig‐Junoy 2010a). Most of these reviews are limited in scope and identified poor quality studies with limited internal and external validity.

Complementary reviews on other pharmaceutical policies include Cochrane reviews of caps and copayments, financial incentives for prescribers, and restrictions on reimbursement (including prior authorisation policies) (Aaserud 2006a; Austvoll‐Dahlgren 2008; Green 2010; Sturm 2007) and another systematic review of prior authorisation of pharmaceutical prescriptions (Puig‐Junoy 2007).

The cost of pharmaceuticals has a tremendous impact on health systems and hence on population health. This is true for high‐income countries and is critical for low‐ and middle‐income countries, where prioritisation of resources is even more essential. Most European countries have adopted reference pricing systems and some Latin American countries, such as Brazil (Espin 2011) and Colombia (Vacca 2011), have pricing policies that use external price referencing.

To our knowledge other systematic reviews of pricing and purchasing policies have not been kept up to date. Our aim was to support informed decisions about pharmaceutical policies and to guide future evaluations by updating a comprehensive summary of what is known from well‐designed research about the effects of alternative pricing and purchasing policies on drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes and costs (expenditures).

Objectives

To determine the effects of pharmaceutical pricing and purchasing policies on health outcomes, healthcare utilisation, drug expenditures (costs) and drug use.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, interrupted time series (ITS) studies (with or without a control group), repeated measures (RM) studies (that is ITS studies where each individual contributed data to each point in time), controlled RM (CRM) and controlled before‐after (CBA) studies.

We only included ITS and RM studies if they had a clearly defined time of intervention and at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention. If a natural transition period was not apparent from the description of the implementation of the intervention a common transition period of two months was used, understood as the period immediately after the intervention point.

For this update we only included CBA and CRM studies if there were at least two sites in each comparison group, due to the EPOC Group recommendation (EPOC 2013a): "We recommend only including cluster randomised trials, non‐randomised cluster trials, and CBA studies with at least two intervention sites and two control sites".

Types of participants

Healthcare consumers and providers within a large jurisdiction or system of care. Jurisdictions could be regional, national or international. Studies within organisations, such as health maintenance organisations, were included if the organisation had multiple sites and served a large population.

Types of interventions

Policies on price and purchasing: policies that determine or are intended to affect the price that is paid for drugs. Included in this category are price control, maximum prices, price negotiations, rebates, reference pricing, index pricing, volume‐based pricing, and procurement policies.

Policies in this review were defined as laws, rules, financial and administrative orders made by governments, non‐government organisations or private insurers. Interventions applied at the level of a single facility were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

To be included a study had to include an objective measure of at least one of the following outcomes:

drug use (prescribed, dispensed or actually used);

healthcare utilisation;

health outcomes;

costs (expenditures), including drug costs and prices, other healthcare costs and policy administration costs.

Any important potential adverse effects of the intervention(s) were addressed.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

· Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), 2012, Issue 10, part of The Cochrane Library. www.thecochranelibrary.com (including the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Register) (searched 22/10/2012)

· MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and MEDLINE 1946 to present, Ovid (searched 22/10/2012)

· EconLit 1969 ‐ , ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012)

· PAIS International, Public Affairs Information Service 1914 ‐ , ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012)

· Worldwide Political Science Abstracts 1975 ‐ , ProQuest (searched 22/10/2012)

· INRUD Bibliography (searched 22/10/2012)

· Embase 1980 to 2010 Week 49, Ovid (searched 14/12/2010)

· NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED) 2010, Issue 4, part of The Cochrane Library.www.thecochranelibrary.com (searched 08/12/2010)

· LILACS, VHL (searched 14/12/2010)

· International Political Science Abstracts (IPSA) 1951 ‐ , Ebsco (searched (17/12/2010)

Searching other resources

Grey Literature

· OpenSIGLE (now called OpenGrey): http://www.opengrey.eu/ (searched 21/12/2010)

· WHOLIS, WHO (the WHO library database): http://dosei.who.int/uhtbin/cgisirsi/Thu+Jul++5+16:26:22+MEST+2012/0/49 (searched 17/12/2010)

· World Bank (Documents and Reports): http://www.worldbank.org/ (searched 21/12/2010)

· Jolis Library Catalog (The Library Network serving the World Bank Group and IMF): http://external.worldbankimflib.org/external.htm (searched 09/10/2011)

· Global Jolis, online catalog for the World Bank Country Office PIC/Libraries (searched 09/10/2011)

· OECD: http://www.oecd.org/ (searched 30/08/2005)

· OECD iLibrary (formerly SourceOECD): http://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/ (searched 30/08/2005)

· World Bank eLibrary: http://elibrary.worldbank.org/ (searched 21/12/2010)

· WHO ‐ The Essential Drugs and Medicines web site: http://www.who.int/medicines/en/ (browsed 21/12/2010)

Trial Registries

· International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Word Health Organization (WHO) http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (searched 23/04/2013)

· ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) http://clinicaltrials.gov/ (searched 23/04/2013)

We also

· We screened the reference lists of all of the relevant reports that we retrieved

· Conducted cited reference searches for all included studies in Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index 1975 ‐ , ISI Web of Knowledge (searched 22/12/2012)

The search strategies for databases and websites are reported in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update six authors (AA, AC, DD, MOA, MM, VV) independently reviewed all of the search results, abstracts and reference lists of relevant reports. The full texts of potentially relevant reports were retrieved (if one or both authors thought they were potentially relevant) and the same two authors independently assessed the relevance of those studies and the limitations of included studies. The lead author (AA) extracted data from new included studies in collaboration with one other author (CV). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, when necessary, including another author (AC) in the discussion. The study selection was performed using Early Review Organizing Software (EROS), a web‐based programme (Ciapponi 2011; Glujovsky 2010).

Data extraction and management

Tables were prepared for each subcategory of interventions including the following information: study identification, characteristics of the intervention, drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes, and costs. These tables formed the basis for the primary analyses. We described potential mechanisms through which the policies were intended to affect drug use and costs and postulated mechanisms for other effects, both intended and unintended. We also briefly listed and described important policy options for which no evaluations were found.

The following information, in addition to details for risk of bias assessment, was extracted from included studies using a standardised data extraction form.

Type of study (randomised trial, non‐randomised trial, repeated measures study, ITS study, CBA study).

Study setting (country, key features of the healthcare system and concurrent pharmaceutical policies).

The sponsors of the study.

Characteristics of the participants (consumers, physicians, practices, hospitals, etc.).

Characteristics of the policies.

Main outcome measures and study duration.

The results for the main outcome measures.

If the study presented results for more than one outcome in each of the four outcome groups (drug use and costs), we chose what we considered the most important outcome in each group, either as specified by the authors or based on discussions among the review authors. We aimed to be parsimonious. However, in cases where additional outcomes might lead to different conclusions, we also included these. We did not otherwise decide which outcomes to include based on the direction or size of effect, or whether a finding was statistically significant.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Five review authors (AA, AC, AM, VC, VV) independently assessed the risk of bias for each new study that was included using the ‘risk of bias’ tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and additional criteria developed by the Cochrane EPOC Group (EPOC 2013a).

The same two review authors updated the risk of bias assessments for studies included in the previous version of this review. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, involving a third review author (AC) if necessary.

For controlled ITS and controlled RM studies, the time series analyses were assessed independently from the controlled comparison, using the above criteria for ITS and CBA studies respectively. If the controlled comparison had a high risk of bias, it was not included and only the ITS analysis was used.

The risk of bias for each bias item and outcome was assessed using the approach described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

| Risk of bias | Interpretation |

| Low risk of bias | Plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results |

| Unclear risk of bias | Plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results |

| High risk of bias | Plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results |

Some setting dependent judgement (that is judgement dependent on knowledge of the setting in which a study was done) was used when assessing overall limitations. Where setting dependent judgement has been used, the explanations are provided in the Risk of bias in included studies (that is part of the Characteristics of included studies tables).

We generated 'risk of bias' summary figures using RevMan 2011.

Measures of treatment effect

ITS and RM studies

The preferred analysis method for ITS and RM studies was either a regression analysis with time trends before and after the intervention, which adjusted for autocorrelation and any periodic changes, or ARIMA analysis. The results of these analyses include changes along two dimensions: change in level and change in slope. Change in level is the immediate effect of the policy and is measured as the difference between the fitted value for the first post‐intervention data point (two months after the intervention) minus the predicted value one month after the intervention based on the pre‐intervention slope only.

Change in slope is the change in the trend from pre‐ to post‐intervention and reflects the 'long' term effect of the intervention. Since the interpretation of change in slope could be difficult, we chose to present the long term effects similarly to the way we calculated and presented the immediate effects. We presented the effects after half a year as the difference between the fitted value for the sixth month post‐intervention data point (half a year after the intervention) minus the predicted outcome six months after the intervention based on the pre‐intervention slope only. The effects after one year and two years were measured similarly. For drug expenditures, we also identified in some included studies cumulative expenditures outcomes (increase or decrease in measures) or if possible we calculated the cumulative savings after a half year, one year and two years as the area between the predicted expenditures curves and the actual expenditures.

Given that policy changes are often announced some months prior to official implementation, we defined a transition phase as the six months from the official announcement. If the included ITS and RM studies stated a different transition phase, we used two months of transition period. All results excluded the transition phase data.

Unit of analysis issues

Comparisons that allocate clusters (for example jurisdictions) but do not account for clustering in the analysis have a potential unit of analysis error, resulting in overly low P values and overly narrow confidence intervals. We planned to reanalyse this kind of comparison if we could extract the intra‐cluster coefficient or obtain missing information from the investigators. However, none of the included studies had unit of analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original investigators to request missing data. If we could not obtain the missing data, we did not make any assumptions about missing data or attempt to impute the missing data.

Data synthesis

If papers with ITS data did not provide an appropriate analysis or reporting of results but presented the data points in a scannable graph or in a table, we (JOJ) reanalysed the data using methods described in Ramsay 2003 and EPOC 2013b. The following segmented time series regression model was specified: Y(t) = B0 + B1*Pre‐slope + B2*Post‐slope + B3*intervention + e(t), where Y(t) is the outcome in month t. Pre‐slope is a continuous variable indicating time from the start of the study up to the last point in the pre‐intervention phase and coded constant thereafter. Post‐slope is coded 0 up to and including the first point post‐intervention and coded sequentially from 1 thereafter. Intervention is coded 0 for pre‐intervention time points and 1 for post‐intervention time points. In this model, B1 estimates the slope of the pre‐intervention data, B2 estimates the slope of the post‐intervention data, and B3 estimates the change in level of outcome as the difference between the estimated first point post‐intervention and the extrapolated first point post‐intervention if the pre‐intervention line was continued into the post‐intervention phase. The difference in slope is calculated by B2 ‐ B1. The error term e(t) was assumed to be first order autoregressive. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated for all effect measures.

In a repeated measures design, the data are repeated outcome measures from many individual patients. If the study did not report appropriate results we did not reanalyse the data from the summary graphs because no estimate of within patient variability could be obtained from the summary graphs and any reanalysis would underestimate or overestimate the standard error of the effect sizes. Therefore, for RM studies we used the results reported in the original papers only.

We conducted a structured synthesis, as described in the EPOC resources for review authors (EPOC 2013c). We anticipated that the included studies would vary with respect to the characteristics of the interventions and the targeted drugs and did not plan on undertaking meta‐analyses. The results of studies of similar interventions (reference pricing, index pricing and maximum prices) that reported similar outcomes were summarised in tables. For reference pricing, the only intervention for which we identified more than one study, we reported median effects and the range of effects. We prepared summary of findings tables using methods developed by the GRADE Working Group (Balshem 2011), described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and recommended by EPOC (EPOC 2013d). We used the GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There was an insufficient number of comparisons for similar outcomes across studies to allow for meaningful exploration of heterogeneity. The following potential explanatory factors were considered: differences in the characteristics of the policies, differences in the settings, and differences in risk of bias (Table 7).

3. Factors that could modify the effects of reference drug pricing.

| FACTOR | CONDITION | POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF CONDITIONS NOT FULFILLED |

| Equivalence of drugs | The drugs in the reference drug group should be therapeutically similar. If they are not, the patients may have to pay more to get the most effective drug ‐ or they may choose less effective drugs | Drug use: Less shift towards cheaper drugs Health: Decrease Healthcare utilisation: Increase Patient drug expenditures: Increased |

| Incentives | Adequate incentives for patients, physicians, pharmacists and pharmaceutical companies to comply with the reference price system | Drug use: Less shift towards cheaper drugs Drug expenditures: Less savings Drug prices: Less reductions |

| Exemptions | Reasonable mechanisms for exemptions for patients that need such for medical reasons. Too limited exemptions could lead to higher co‐payments of the most effective drug and to prescribing of less effective drugs by physicians. Too generous exemptions could reduce the savings, by not shifting the drug use towards cheaper drugs | Drug use: Less shift towards cheaper drugs Health: Decrease Healthcare utilisation: Increase Patient drug expenditures: Increased |

| Availability of drugs | The reference drugs and other cheap drug choices of the reference groups should be available. If not, more expensive drugs would be used | Drug expenditures: Less savings Drug prices: Less reductions |

| Price levels | To achieve savings there should be significant price differences between the drugs in a reference group before the reference price system is introduced, with relatively high prices on the drugs most used | Drug expenditures: Less savings Drug prices: Less reductions |

| Electronic information systems | The administration costs, like time use for identifying, prescribing and dispensing the reference drugs and for handling exemption cases should be as low as possible. An electronic processing system would be useful and potentially time saving | Drug use: Less shift towards cheaper drugs Drug expenditures: Less savings Drug prices: Less reductions |

In addition, we attempted to identify important factors that might be taken into consideration by anyone contemplating implementing any of the policy alternatives, including: possible trade‐offs (of the expected benefits versus harms and costs), short versus long term effects, indications and contraindications for when the polices might be used, limitations of the available evidence, and other important factors that might affect the translation of the available evidence into practice in specific settings.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

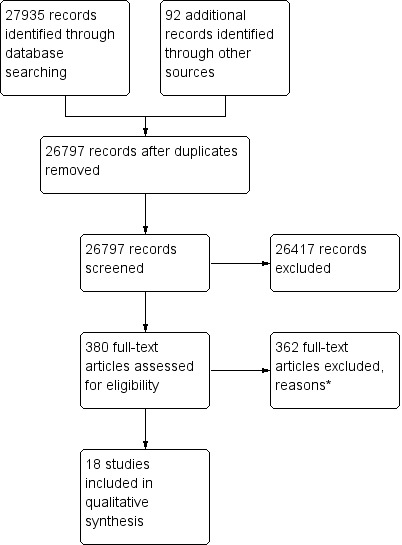

The literature search for pharmaceutical pricing policies in databases and websites, including reference lists from relevant studies and reports, resulted in 26,797 references after removing duplicates(9265 of them identified through the new search). We identified and retrieved in full text a total of 380 papers (134 of them from the new search) that were potentially relevant; 362 (125 from the current update) of these papers were excluded, most of them because they did not meet the study design inclusion criterion. They were primarily reviews, editorials, modelling studies, cross‐sectional studies, and before‐after studies without a control group. Finally 18 studies were included (seven from the current update): Brekke 2011; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Kibicho 2012; Moreno‐Torres 2011; Puig 2007; Stargardt 2010 (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

* Out of 125 full‐text reports excluded in the update, 49 did not meet study design criteria, 64 did not meet intervention criteria, 3 did not meet outcome criteria, 2 were duplicated and 4 for other reasons.

Two studies (Huang 2012; Lee 2006) were identified and judged to possibly meet the inclusion criteria. These studies are listed amongst studies awaiting assessment because responses following contacting the first author and additional information are still pending. These two references described multiple pricing policy interventions from Tawian (1997 to 2002): stepwise price adjustments, external reference pricing, and internal reference pricing for generic drugs groups. Because of the short period before and after each intervention the review authors required more information about interventions and the size and effects of outcomes.

Included studies

Eighteen papers met the inclusion criteria (Aronsson 2001; Brekke 2003; Brekke 2011; Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Kibicho 2012; Marshall 2002; McManus 2001; Moreno‐Torres 2011; Narine 2001; Pavcnik 2002; Puig 2007; Sawyer 1983; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003; Stargardt 2010).

Study designs

None of the studies were randomised or non‐randomised trials. All 18 included studies used ITS or RM analyses. Some of the studies had more than one design, that is different designs for different outcomes. Four studies included in the original review used a CRM or CBA studies design to assess the health outcome or healthcare utilisation outcomes (Grootendorst 2002; Hazlet 2002; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003); these studies were excluded from summary of findings (SOF) tables and from the main report in this update according to an EPOC Group recommendation (August 2013): “We recommend only including cluster randomised trials, non‐randomised cluster trials, and CBA studies with at least two control sites”. See Characteristics of included studies.

Characteristics of settings and patients

Seven of the reference pricing studies (Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Marshall 2002; Narine 2001; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003) were from Canada (British Columbia), two were from Germany (Pavcnik 2002; Stargardt 2010), and there was one study from each of the following countries: the USA (Maryland) (Sawyer 1983), Australia (McManus 2001), Sweden (Aronsson 2001) and Spain (Puig 2007). The index pricing study was from Norway (Brekke 2003) and the maximum prices study was from Spain (Puig 2007). The setting in all the Canadian studies was the British Columbia Ministry of Health's drug subsidy program, Pharmacare. The patients in all these studies were Pharmacare beneficiaries: senior citizens aged 65 years and older. The settings in the other studies were the national drug insurance plans, including all beneficiaries (Australia, Norway, Sweden), the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) plan (Germany) and Medicaid (USA). The SHI plan in Germany covers about 88% of the population. It is compulsory for workers with incomes under a certain level, for unemployed and retired people, and for specific population groups such as farmers, artists and students. The state specific Medicaid programs in the USA provide medical benefits to low‐income groups, medically needy groups, or special groups.

Setting

Canada (eight studies: Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Marshall 2002; Narine 2001; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003); German (two studies: Pavcnik 2002; Stargardt 2010); US (two studies: Kibicho 2012; Sawyer 1983); Spain (two studies: Moreno‐Torres 2011; Puig 2007); Norway (two studies: Brekke 2003; Brekke 2011); Sweden (one study: Aronsson 2001); Australia (one study: McManus 2001).

Characteristics of interventions

In 17 studies the effects of reference drug pricing were analysed (Aronsson 2001; Brekke 2011; Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Kibicho 2012; Marshall 2002; McManus 2001; Moreno‐Torres 2011; Narine 2001; Pavcnik 2002; Puig 2007; Sawyer 1983; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003; Stargardt 2010). One of these studies (Puig 2007) analysed maximum prices policy. The one other study analysed effects of index pricing (Brekke 2003). See Characteristics of included studies for more details.

Policies in the first included studies were mainly introduced in the 1990s, except for the Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) policy in Maryland, USA (1970s). The years of introduction of policies of the new included studies were 1995 to 1997 for Grootendorst 2005 and Grootendorst 2006; 2000 for Moreno‐Torres 2011; 2003 for Brekke 2011 and Kibicho 2012; 2004 for Puig 2007; and 2005 for Stargardt 2010.

The setting in all the Canadian studies was the British Columbia Ministry of Health’s drug subsidy program, Pharmacare. The patients in all these studies were the Pharmacare beneficiaries, senior citizens aged 65 years and older (Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Marshall 2002; Narine 2001; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003). The settings in the other studies were the National Public Insurance from Sweden and Norway (Aronsson 2001; Brekke 2003; Brekke 2011), the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme from Australia (McManus 2001). Germany has two types of settings: the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) in Germany covers about 88% of the population that is compulsory for workers with income under a certain level, for unemployed and retired people, and for specific population groups such as farmers, artists and students (Pavcnik 2002); and the Techniker Krakenkasse (TK), a sickness fund with more than 5.8 million insured members in 2005, which is 82% of German residents with public health insurance (Stargardt 2010). The state specific Medicaid programs in the USA provide medical benefits to low‐income groups, medically needy groups, and special groups; one study setting was from the Maryland State (Sawyer 1983), and other from Michigan State (Kibicho 2012). Spanish settings corresponded to the National Health System (Moreno‐Torres 2011; Puig 2007) and the Andalusian Public Health Service (Puig 2007). See 'Additional table 2' for further details.

For all seven British Columbia studies RP policy interventions and outcomes were for large therapeutic groups of analogue drugs: angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), nitrates used for long term prophylaxis, histamine‐2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), opiates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; Marshall 2002; Narine 2001; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003). Other studies were a German study for statins (Stargardt 2010), a German study for oral antidiabetics and antiulcer drugs (Pavcnik 2002), and a US study for antihypertensive and antihyperlipidaemic drugs (Kibicho 2012). No information was given on the infrastructure around the policies, for example what kind, if any, of electronic systems for prescription claims. For all included drug classes there were special authority exemptions, which were valid indefinitely and given after the physician had applied and provided a valid reason for exemption, for example in British Columbia there were several exemptions in the reference price system.

Some studies described RP policies applied for international non‐proprietary name drugs: one Australian study for ranitidine (McManus 2001); acetaminophen‐codeine (Grootendorst 2005); and atorvastatin (Stargardt 2010). Other studies reported intervention with a RP policy for generic grouping drugs: one Spain study (Moreno‐Torres 2011) and one Norwegian study (Brekke 2011) for citalopram, omeprazole and cetirizine brand names and generic drugs. One US study described RP applied for dosage forms of multisource chemical entities (Sawyer 1983). No information was provided for exemptions with this type of drug included in the analysis.

A Norwegian study (Brekke 2003) included an index pricing policy for six groups of active substances: cetirizin (treatment of allergy), citalopram (antidepressant), enalapril (antihypertensive), lisinopril (antidepressant), loratadin (treatment of allergy) and omeprazol (treatment of gastro‐intestinal disorders). An exemption to this intervention was the case when the prescribing physician proscribed substitution of a generic in the pharmacies. A Spanish study (Puig 2007) reported maximum prices for 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐ conenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase inhibitors and a group of six particular compounds (statins) sold primarily in oral dosage forms (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, and cerivastatin). No information was provided for exemptions with this type of drugs included in the analysis. See 'Additional table 2' for further details.

There was little information on specific incentives in the studies. The general incentives in reference pricing systems are described in the 'Background' section.

Few of the included studies reported the size of the difference between the reference price and other drugs in the relevant drug groups. Not much specific information was given in the studies on what incentives the physicians or pharmacists had to spend time on identifying and retrieving the reference drug, or whether this was facilitated in some way (for example through an automated system). However, in British Columbia the reference drug program was introduced at the same time as a province‐wide online pharmacy network was established. The pharmacy network kept track of exempt patients, indicated the portion of the drug price that PharmaCare would cover, and relieved the patient of the responsibility of submitting claims to PharmaCare and of the need to understand complicated policies (Pharmanet 2003; Pharmanet 2005).

Characteristics of outcomes

None of the studies presented data on all outcomes. The studies provided data on cumulative drug expenditures (six studies: Brekke 2011; Grootendorst 2002; Kibicho 2012; Marshall 2002; Puig 2007; Moreno‐Torres 2011); third party (insurance) drug expenditures (eight studies: Brekke 2011; Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Marshall 2002; Sawyer 1983; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003); drug use, that is either the number of dispensed doses or the number of dispensed prescriptions (10 studies: Grootendorst 2002; Grootendorst 2005; Grootendorst 2006; Hazlet 2002; McManus 2001; Moreno‐Torres 2011; Narine 2001; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003; Stargardt 2010); and drug prices (four studies: Aronsson 2001; Brekke 2011; Kibicho 2012; Pavcnik 2002). One study (Grootendorst 2005) reported patient costs but no other study reported other costs (either intervention costs or costs in other parts of the health services sector) using one of the study designs specified in our inclusion criteria.

Excluded studies

The excluded studies table provides the reasons for exclusion of 24 studies about which it was plausible to expect that a reader would question why the study was not included, that are well known but did not meet all of the inclusion criteria, or ITS studies that met all inclusion criteria except that there were too few data points. See Characteristics of excluded studies for more details.

Risk of bias in included studies

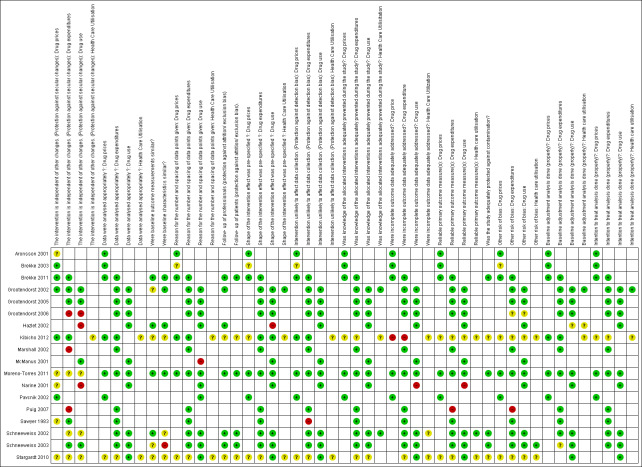

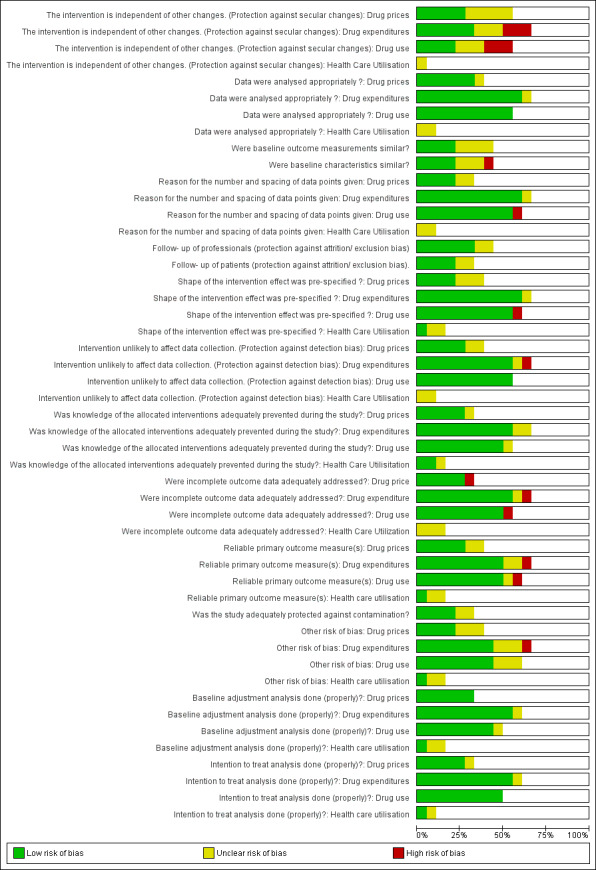

See: Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

In August 2013 the EPOC Cochrane Group recommended only including cluster randomised trials, non‐randomised cluster trials, and CBA studies with at least two intervention sites and two control sites to reduce the risk of bias. Due to this recommendation we excluded four originally included studies (Grootendorst 2002; Hazlet 2002; Schneeweiss 2002; Schneeweiss 2003) from the SOF tables and from the main report on outcomes for healthcare utilisation; and included only two of these studies for mortality (Grootendorst 2002; Schneeweiss 2002).

For the reference pricing the following studies presented high risk of bias in certain domains: Hazlet 2002 (protection of secular changes, and shape of the curve not pre‐specified); Kibicho 2012 (incomplete outcome data adequately addressed); Marshall 2002 (protection of secular changes); Narine 2001 (protection of secular changes, management of incomplete data, and reliable outcome measurement); Sawyer 1983 (protection against detection bias); and Schneeweiss 2003 (similar baseline characteristics) (see Figure 2 and Characteristics of included studies).

The included ITS study (Puig 2007) for maximum pricing policy had limitations in assessing drug expenditures: the intervention could be not be protected from secular changes, the outcome could not be measured in a reliable way, and the use of overall volume of sales as a proxy for public expenditure data.

The included ITS study (Brekke 2003) for index pricing had some limitations (the source of data collection changed during the study period).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Reference pricing policy compared to no reference pricing.

| Reference pricing policy compared to no reference pricing | |||

| Population: Patients with drug insurance Settings: Canada, US, Germany Intervention: Reference pricing Comparison: No reference pricing | |||

| Outcomes |

Impact Median relative effect (range) |

No of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Insurer's cumulative drug expenditures one year after the transition period | Reference drugs + cost share drugs: Median relative cumulative drug expenditures of ‐18% (range: from ‐36% to 3%) | 2 studies1 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Insurer's drug expenditures one year after the transition period | Reference drugs + cost share drugs: Median relative drug expenditures of ‐10% (range: from ‐53% to 4%) | 4 studies2 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Drug use one year after the transition period | Reference drugs: Median relative change in prescriptions of 15% (range: from ‐14% to 166%) | 4 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Cost share drugs: Median relative change in prescriptions of ‐39% (range: from ‐87% to ‐17%) | 3 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Healthcare utilisation | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health outcomes | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Reference drugs: drugs that determine the reference price level. There is no cost share by the patients for these drugs, which are fully reimbursed. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to an increase in use of these drugs.

Cost share drugs: drugs in the same group as the reference drugs that cost more. Patients have to pay the difference between reference price drugs and the price of these drugs. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to a decrease in use of these drugs. Reference drugs + cost share drugs: both the reference drugs and the cost share drugs. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to little or no change in the overall use of these drugs. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1. Puig 2007 was not considered for the median because this study reported the outcome different than the other two studies (mean monthly savings of total lovastatin and simvastatin sales).

2. We only included Pharmacare data from Grootendorst 2005.

Summary of findings 2. Index pricing compared to no index pricing.

| Index pricing compared to no index pricing | |||

| Population: Norwegian citizens taking one of the following drugs: citalopram (depression), omeprazol (antiulcer), cetirizin (allergy), loratadin (allergy), enalapril (high blood pressure) and lisinopril (high blood pressure), simvastatin (high cholesterol) or amlodipin (high blood pressure) Settings: Norway Intervention: Index pricing Comparison: No index pricing | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Drug use 6 months after policy start date | Generic citalopram: 55% (95% CI 11 to 98%) Brand citalopram: ‐43% (95% CI ‐67 to ‐18%) |

1 study | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Drug prices 6 months after policy start date | Generic drug prices: ‐5.3% (95% CI NA) Brand drugs prices: ‐1.1% (95% CI NA) |

1 study | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Drug expenditures | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Healthcare utilisation | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health outcomes | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| CI: Confidence interval | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Summary of findings 3. Maximum prices compared to no maximum prices for drug expenditures.

| Maximum prices compared to no maximum prices for drug expenditures | |||

| Population: Patients taking statins Settings: Andalusia, Spain Intervention: Maximum prices Comparison: No maximum prices | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Drug expenditure one year after the transition period | 21.4% (95% CI 19.0 to 23.7%) in volume of sales for total statins | 1 study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1 |

| Drug prices | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Healthcare utilisation | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health outcomes | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Drug use | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events | No studies meeting the inclusion criteria were found | ‐ | ‐ |

| CI: Confidence interval | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 High risk of bias due to the intervention not being independent of other changes.

Summary of findings 4. Reference pricing versus no reference pricing: drug expenditures.

| STUDY ID | REFERENCE PRICE FOR | EFFECTS ON EXPENDITURES OF*** | OUTCOME | ABSOLUTE CHANGE LEVEL, IMMEDIATE AFTER TRANSITION PERIOD (95% CI) | RELATIVE CHANGE IN LEVEL, IMMEDIATE AFTER TRANSITION PERIOD (95% CI) | RELATIVE CHANGE IN LEVEL, 1/2 YEAR AFTER TRANSITION PERIOD (95% CI) | RELATIVE CHANGE IN LEVEL, 1 YEAR AFTER TRANSITION PERIOD (95% CI) | RELATIVE CHANGE IN LEVEL, 2 YEARS AFTER TRANSITION PERIOD (95% CI) | NOTES |

| Grootendorst 2002* | ACE inhibitors | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | ACE inhibitors. Pharmacare expenditure per 100,000 senior citizens. Canadian dollar per month | 18,203 (‐1611 to 38,017) | 5% (0% to 10%) | 5% (‐2% to 10%) | 4% (‐3% to 10%) | 1% (‐8% to 9%) | Price year not specified in study papers |

| CCBs | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | CCBs. Pharmacare expenditure per 100,000 senior citizens. Canadian dollar per month | ‐91,547 (‐122,082 to ‐61,011) | ‐19% (‐26% to ‐13%) | ‐18% (‐30% to ‐5%) | ‐16% (‐36% to 5%) | ‐14% (‐51% to 23%) | Price year not specified in study papers | |

| Nitrates | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | Nitrates. Pharmacare expenditures per 100,000 senior citizens. Canadian dollar per month | ‐66,473 (‐72,620 to ‐60,326) | ‐50% (‐55% to ‐46%) | ‐47% (‐52% to ‐41%) | ‐ | ‐ | Price year not specified in study papers | |

| Grootendorst 2005 | NSAIDs (RP 1) | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | Average monthly expenditure per day of therapy dispensed (Canadian dollars 2004) for Pharmacare (Ph) and Patient (Pa) | Ph:‐0.08 (‐0.12 to ‐0.04) Pa: 0.00 (‐0.03 to 0.02) |

Ph: ‐9.6% (95% CI NA) Pa: NA |

‐ | Ph: ‐8.8% (95% CI NA) Pa: 690% (95% CI NA) |

Ph: ‐8.3% (95% CI NA) Pa: 571% (95% CI NA) |

Last estimated effect at 19 months |

| NSAIDs (RP 2) | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | Average monthly expenditure per day of therapy dispensed (Canadian dollars 2004) for Pharmacare (Ph) and Patient (Pa) | Ph:‐0.31 (‐0.36 to ‐0.27) Pa: 0.07 (0.04 to 0.10) |

Ph: ‐37% (95% CI NA) Pa: 550% (95% CI NA) |

‐ | Ph: ‐53% (95% CI NA) Pa: 500% (95% CI NA) |

‐ | ||

| Marshall 2002* | H2RAs | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | H2RAs. Pharmacare expenditures per 100000 senior citizens. Canadian dollar per month | ‐45,139 (‐50,096 to ‐40,183) | ‐39% (‐44% to ‐35%) | ‐38% (‐44% to ‐31%) | ‐35% (‐45% to ‐25%) | ‐30% (‐48% to ‐12%) | Price year not specified in study papers |

| Grootendorst 2006 | ACE inhibitors | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | All ACE inhibitors. Drug plan expenditures per DDD dispensed. CAD | ‐0.04 (‐0.09 to 0.02) | ‐4% (95% CI NA) | ‐7% (95% CI NA) | ‐11% (95% CI NA) | Price specified in study papers | |

| CCBs | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | All CCBs. Drug plan expenditures per DDD dispensed. CAD | ‐0.20 (‐0.25 to ‐0.15) |

‐16% (95% CI NA) | ‐10% (95% CI NA) | ‐4% (95% CI NA) | Price year not specified in study papers | ||

| Sawyer 1983 | 52 dosage forms of 25 multisource chemical entities | Reference drugs + cost share drugs | Monthly Medicaid drug expenditures in Maryland. USD | ‐291276 (‐478,458 to ‐104,094) | ‐0.87 per month (95% CI NA) | Price year not specified in study papers | |||

| Brekke 2011 | The RP covered six chemical substances: Citalopram, Omeprazol, Cetirizin, Loratadin, Enalapril and Lisinopril . The system was later extended with two additional substances; simvastatin and amlodipin | Cost share drugs | Change in copayments NOK | Generic copayment ‐12.92 (95% CI NA) Brand‐name copayment ‐6.37 (95% CI NA) |

Generic copayment ‐12.76% (95% CI NA) Brand‐name copayment ‐14.82% (95% CI NA) |

||||

*Results from reanalysis by reviewers.

**NA = Not available.

***EFFECTS ON EXPENDITURES OF:

Reference drugs, drugs that determine the reference price level. There is no cost share by the patients for these drugs, which are fully reimbursed. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to an increase in use of these drugs. Cost share drugs, drugs in the same group as the reference drugs that cost more. Patients have to pay the difference between reference price drugs and the price of these drugs. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to a decrease in use of these drugs.

Reference drugs + cost share drugs, both the reference drugs and the cost share drugs. The expectation is that reference pricing will lead to little or no change in the overall use of these drugs.

Detailed results for the included studies are provided in the 'Additional tables' (Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13; Table 14). None included reference reported adverse effects caused by pricing policy interventions. There was no information in the included studies regarding the differential effects of the interventions on resource‐disadvantaged populations.

4. Reference pricing versus no reference pricing: Cumulative drug expenditures.