Abstract

Voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) allow the passage of Ca2+ ions through cellular membranes in response to membrane depolarization. The channel pore-forming subunit, α1, and a regulatory subunit (CaVβ) form a high affinity complex where CaVβ binds to a α1 interacting domain in the intracellular linker between α1 membrane domains I and II (I–II linker). We determined crystal structures of CaVβ2 functional core in complex with the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II linkers to a resolution of 1.95 and 2.0 Å, respectively. Structural differences between the highly conserved linkers, important for coupling CaVβ to the channel pore, guided mechanistic functional studies. Electrophysiological measurements point to the importance of differing linker structure in both CaV1 and 2 subtypes with mutations affecting both voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation and voltage dependence of activation. These linker effects persist in the absence of CaVβ, pointing to the intrinsic role of the linker in VDCC function and suggesting that I–II linker structure can serve as a brake during inactivation.

Introduction

Voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) allow the selective passage of Ca2+ ions through cellular membranes in response to membrane depolarization, playing a major role in many neuronal and other physiological processes (for review, see Jones, 1998). CaV1 and CaV2 comprise two heteromeric VDCC families characterized by high depolarization thresholds required for their activation. α1 is the membrane pore-forming subunit. Consisting of four homologous domains, it forms a pseudo-tetrameric structure. Each domain contains six membrane helical segments, where S1-4 constitute the voltage sensor and S5-6 the ion-selective pore. The cytoplasmic β subunit (CaVβ) is tightly associated with CaV1 and CaV2 α1subunits and robustly modulates their function (for review, see Buraei and Yang, 2010). CaVβ both facilitates channel localization to the plasma membrane and directly modulates its gating properties. Its effects include hyperpolarization of the activation voltage, acceleration of activation kinetics, and increase of channel open probability (Buraei and Yang, 2010). Furthermore, several aspects of both voltage and calcium-dependent inactivation (VDI and CDI) are differentially affected by various CaVβ isoforms. The functional core of CaVβ is composed of two conserved structural domains, a SH3 and a guanylate-kinase (GuK) like domain. The CaVβ GuK domain interacts with a conserved 18-residue region in the intracellular linker between α1 domains I and II, dubbed AID (α1 interacting domain) (Pragnell et al., 1994). Crystallographic studies have shown how the AID α-helix docks into a deep hydrophobic groove in the GuK domain (Chen et al., 2004; Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004).

The cytoplasmic I–II linker/CaVβ interaction is functionally important in all CaV1 and CaV2 channels. Nonetheless, the exact molecular mechanisms leading to its effects on channel gating are not completely understood. The localization of the AID in relation to IS6, a part of the α1 inner pore, suggests that a mechanism of the I–II linker/CaVβ complex may involve constraints on IS6 mobility. As previously suggested, CaVβ association promotes an α-helical conformation on the AID (Opatowsky et al., 2004). This α-helix is predicted to propagate through the proximal linker (PL) to IS6 (Fig. 1A), forming a rigid connection between the GuK of CaVβ and the channel pore, mechanically transducing its binding to channel gating states. (Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004). Thus, gaining structural knowledge of the regions of the I–II linker outside the AID has been an important requirement for further understanding the mechanism of VDCC modulation by the I–II linker/CaVβ complex. We sought to obtain structural features of the intact I–II linker in complex with CaVβ, including whether the PL is one long α-helix. Using I–II linkers from both the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 α1 subunits, we discern distinctive structural variations between I–II linker/CaVβ complexes of these different channel subtypes. While the CaV2.2 PL is mostly α-helical, the CaV1.2 PL helix begins at a downstream glycine conserved in CaV1 channels. We tested the consequences of these subtype-specific structural variations on the biophysical properties of intact VDCCs. Our functional results show divergent, channel-type PL secondary structure to be important for various channel functional properties including VDI, CDI, and the voltage dependence of activation.

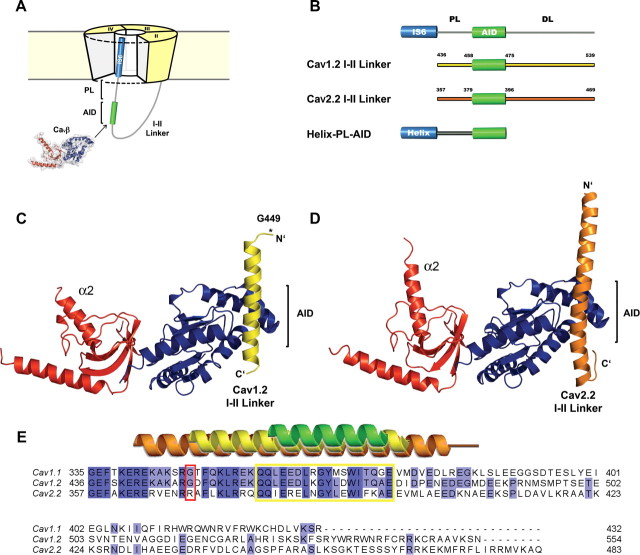

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 core complexes. A, Diagram representation of a VDCC. The PL region bridges the α1 transmembrane IS6 pore α-helix (blue) and the AID (green). B, Schematic illustration of the I–II linker constructs. Both I–II linker constructs used for crystallography were coexpressed with CaVβ2 functional core (Opatowsky et al., 2004). In the Helix-PL-AID constructs used for CD measurements, the blue cylinder represents an 18-residue high helical-propensity sequence (Baldwin, 1995), fused upstream to the PL-AID regions. C–D, Ribbon depiction of the CaV1.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 (C) and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 (D) crystal structures. While in CaV2.2, the helix extends upstream of the AID, almost to its N terminus; the helical extension in the CaV1.2 PL is much shorter and breaks at a conserved glycine (G449). E, Multiple sequence alignment of the rabbit CaV1.1, CaV1.2, and CaV2.2 I–II linkers. Secondary structure of modeled residues from 1T3L (green), CaV1.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 (yellow), and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 (orange), is presented above. The AID region is framed in yellow. The critical PL glycine residues are framed in red.

Materials and Methods

Molecular cloning.

For crystallography, rabbit CaV1.2 (P15381, residues 436–539) and CaV2.2 (Q05152, residues 358–468) I–II linkers were subcloned downstream to a HisTag and a Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site between NcoI and EcoRI restriction sites of pET-Duet-1 (Novagen). The CaVβ2 functional core (Opatowsky et al., 2003) sequence was subcloned between NdeI and KpnI sites. For CD spectroscopy, a maltose-binding protein (MBP) sequence downstream of a HisTag and upstream of a TEV site was inserted between NcoI and BamHI sites of a pET-28a vector (Novagen). A synthetic DNA fragment encoding an 18 aa α-helical peptide (3×AAKAAE) flanked between a BamHI site at its 5′ and sequential NheI and NotI sites at its 3′ was ligated into this vector between BamHI and NotI sites. Subsequently, PL-AID fragments, encoding CaV1.2 residues 436–475 and CaV2.2 357–396, of wild-type (WT) and mutant channel sequences were subcloned between NheI and NotI sites of this modified vector.

For electrophysiology, the following cDNAs were used: rabbit CaV1.2 (X15539), CaVβ2b (L06110), α2δ-1 (P13806) (Shistik et al., 1998), and rabbit CaV2.2 α1(D14157). All constructs included a T7 promoter sequence for RNA transcriptions. RNA transcripts included 5′ and 3′ untranslated sequences of Xenopus β-globin. For further Cav2.2 manipulations, silent mutations were introduced into the gene sequence to generate an EcoRV/SpeI cloning cassette between nucleotides 945–1716. Using either overlapping PCR or site directed mutagenesis, PL mutations were introduced into this cassette. In CaV1.2 PL, the naturally occurring double restriction site for SfiI in this gene sequence was used as a cloning cassette (nucleotides 264–1572 of CaV1.2). m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G capped RNA was prepared by in vitro transcription using the Ribomax Large Scale RNA production system (Promega). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed using MicroSpin G-25 columns (GE Healthcare).

Protein expression and purification.

All expression vectors were transformed into E. coli Tuner (DE3) Codon Plus competent cells. Cells were grown in 2 × YT media plus antibiotics. Expression was induced with IPTG at 16°C. Cells were harvested 12–16 h after induction and stored at −80°C.

Purification of the I–II linker/β2 complexes: Cells suspended in phosphate buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate pH 8.0, 0.3 m NaCl) plus 0.1% Triton X-100, 15 U/ml DNase, lysozyme, and 1 mm PMSF were lysed by microfluidizer and subjected to 1 h centrifugation at 38,700 × g. The soluble fraction was purified by sequential Ni2+ chelate, anion-exchange [Q-Sepharose (GE Healthcare)] and size-exclusion [Superdex-200 HiPrep (GE Healthcare)] column chromatography, including removal of the HisTag by TEV proteolysis. Final buffer conditions were 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 m NaCl, and 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol.

Purification of the Helix-PL-AID peptides: lysate preparation and subsequent purification were similar as above using a phosphate buffer including 20% glycerol without the anion-exchange step. For size-exclusion chromatography a Superdex-75 Hi-prep (GE Healthcare) column was used, with final buffer conditions of 10 mm sodium phosphate pH 8.0, 0.2 m NaCl.

Crystallography.

CaV2.2 I–II linker/β2 complex crystallization: Plate-shaped crystals appeared using vapor diffusion with 0.1 m NaCl, 0.1 m bicine, pH 7.6–8.35, 23–26% PEG 400 (Fluka) at 19°C with a 1:1 protein (13 mg/ml) to reservoir ratio. Macroseeding and microseeding (McPherson, 1999) methods were used to improve crystal dimensions. Before crystal flash-freezing, an eightfold volume of a solution containing 40% (w/v) PEG 400, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 m bicine, 0.1 m NaCl was gently added to the crystallization drop and air dehydrated for 0.5–2 h (Haebel et al., 2001). For the bromide-soaked datasets, after dehydration, crystals were transferred to a drop containing 55% (w/v) PEG 400, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 m bicine, pH 8.05, 0.1 m NaCl, 1 m NaBr and soaked for 30–60 s before flash-freezing in cryo-loops.

CaV1.2 I–II linker/β2 complex crystallization: Prism shaped crystals appeared using vapor diffusion methods at 1.1–1.25 m potassium sodium tartrate, 0.1 m Tris, pH 7.0–8.0, at 19°C at 1:1 protein (8 mg/ml) to reservoir ratio plus microseeding seedstock. To minimize crystal cracking in the cryoprotectant solution, a gentle chemical cross-linking method was used in which glutaraldehyde was introduced into the crystal by vapor diffusion (Lusty, 1999). Immediately after this 1 h process, the crystals were soaked for 30–60 s in 1.25 m potassium sodium tartrate, 0.1 m Tris, pH 7.85, 12% (w/v) sucrose, 1 m NaBr or 1 m KI (for bromide or iodide datasets) and then flash-frozen for data collection.

All x-ray diffraction measurements were conducted at 100° K. For both crystal forms, anomalous data were collected at the Br anomalous absorption peak. Intensities were integrated, scaled, and merged with the HKL2000 software (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Crystal unit cell parameters, crystallographic symmetry, and data statistics are summarized in Table 1. In both cases, cell volumes were appropriate for only one complex per asymmetric unit. Preliminary partial phases of each of the complexes were obtained by molecular replacement (MR) with MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov, 1997), using the CaV1.1 AID/β2 complex [(Opatowsky et al., 2004), PDB:1T3L] as a search model, and rigid body refinement in REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997). Anomalous difference Fourier maps were directly calculated using these partial phases. With the halide substructure of the five highest peaks from each of the difference Fourier maps, phases from SHARP (de La Fortelle and Bricogne, 1997) were computed. Additional halide atom sites were revealed for each of the substructures in residual maps during several rounds of SHARP refinement. The phases were further improved using the programs DM (Cowtan and Zhang, 1999) and SOLOMON (Abrahams and Leslie, 1996) in the SHARP density modification interface.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data collection and phasing statistics | Cav1.2 I–II linker/Cavβ2 core |

Cav2.2 I–II linker/Cavβ2 core |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I−(1) | I−(2) | Br− | Native | Br−(1) | Br−(2) | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.240 | 1.542 | 0.918 | 0.873 | 0.918 | 0.918 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = 52.7 | a = 53.4 | a = 53.3 | a = 36.9 | a = 36.5 | a = 36.9 |

| b = 70.2 | b = 71.0 | b = 70.5 | b = 67.7 | b = 67.6 | b = 68.2 | |

| c = 134.7 | c = 134.6 | c = 134.3 | c = 79.2 | c = 77.5 | c = 78.4 | |

| β = 102.5 | β = 102.0 | β = 102.3 | ||||

| Total reflections | 618109 | 703778 | 1104840 | 583596 | 358991 | 926807 |

| Unique reflections | 22964 | 14694 | 37774 | 26222 | 14590 | 15003 |

| Completeness (%)a | 97.6 (88.2) | 99.1 (99.2) | 91.0 (36.7) | 90.1 (53.6) | 90.1 (55.1) | 90.1 (51.2) |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 6.7 (26.7) | 9.3 (33.4) | 7.9 (38.8) | 7.6 (42.1) | 6.2 (23.9) | 6.7 (22.7) |

| I/σa | 18.7 (3.7) | 15.1 (3.3) | 17.23 (1.2) | 16.4 (1.7) | 18.2 (2.9) | 17.1 (2.8) |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30–2.30 | 30–2.70 | 30–1.95 | 30–2.00 | 30–2.40 | 30–2.40 |

| f'/f″ | −0.21/4.76 | −0.58/6.83c | −8.54/3.82 | −8.54/3.82 | −8.54/3.82 | |

| Phasing power (anomalous) | 1.079 | 1.206 | 0.677 | 0.447 | 0.326 | |

| Phasing power (isomorphous) | 0.727 | 1.266 | 0.412 | 0.750 | ||

| Figure of merit | 0.317 | 0.474 | ||||

| Beamline (ESRF/Homesource) | BM-14 | Raxis-IV | BM-14 | ID-23-2 | BM-14 | BM-14 |

| No. of reflections (working/test) | 34543/1813 | 22583/1235 | ||||

| dmin (Å) | 1.95 | 2.0 | ||||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 19.9/22.9 | 19.8/23.8 | ||||

| Rms deviation from ideality: | ||||||

| Bond lengths | 0.006 | 0.008 | ||||

| Bond angles | 1.03 | 1.032 | ||||

| B factors (Å2) (Rmsd of bonded atoms—main/side chain) | 2.18/3.94 | 2.50/4.53 | ||||

| Averaged B factor (Å2) | 47.05 | 50.79 | ||||

| No. of protein atoms/solvent | 2432/175 | 2666/162 | ||||

aValues of the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses.

bRmerge = ΣhklΣi| Ihkl,i − 〈I〉hkl|/ΣhklΣi |Ihkl,i|, where Ihkl is the intensity of a reflection and 〈I〉hkl is the average of all observations of this reflection.

cf'/f'′ values were refined.

Model building was performed first automatically by the program ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al., 1999) and completed manually by COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). Atomic coordinate refinement was performed by alternating use of Phenix (Müller et al., 2010), CNS (Brünger et al., 1998), or REFMAC5 with rounds of manual rebuilding. Solvent molecules were added by automatic solvent building in ARP/wARP. The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. All molecular graphics were generated using PYMOL (Schrödinger, version 1.3r1). Structure superimposition was done using the “Align” function in PYMOL.

Electrophysiology.

Xenopus laevis maintenance and oocyte preparation were as described previously (Shistik et al., 1998). Oocytes were injected with RNA 3–5 d before the experiment. Due to lower channel surface expression, longer incubation time was used for oocytes not injected with CaVβ (up to 10 d). In all experiments unless specified, β2b and α2δ-1 auxiliary subunits RNAs were coinjected with that of the α1 subunit in equivalent amounts to the injected α1. Amounts of injected RNA per oocyte were as follows: CaV2.2, 0.2–5 ng; CaV1.2, 2.5–5 ng; CaV2.2 (without β), 7.5–20 ng; CaV1.2 (without β), 7.5–20 ng. Whole-cell two-electrode voltage clamp recordings were performed using the Gene Clamp 500 amplifier (Molecular Devices). To block the oocyte endogenous Ca2+-dependent Cl− currents, 25–30 nl of 100 mm of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA were routinely injected into the oocytes 0.5–3 h before current recording. Bath perfusion solution contained 50 mm NaOH, 2 mm KOH, 5 mm HEPES (titrated to pH 7.5 with methanesulfonic acid), and 40 mm of either Ba(OH)2 or Ca(OH)2. Current–voltage (I–V) relations were measured with 500 pulses from holding potential of −80 mV to test potentials of −50 mV to +50 mV in 10 mV steps. For each cell, the net VDCC currents were obtained by subtraction of the residual currents recorded with the same protocols after blocking the channels with 200–400 μm CdCl2.

Data acquisition and analysis were performed using pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices). I–V relations were fitted with a standard Boltzmann equation in the form: I = Gmax(Vm − Vrev)/(1 + exp(−(Vm − V0.5 /Ka))), where V0.5 is the half-maximal activation voltage, Ka is the slope factor, Gmax is the maximal conductance, Vm is membrane voltage, I is the current measured at the specific Vm, and Vrev is the reversal potential. Conductance-voltage (G–V) relations were obtained using the V0.5 and Ka values from the I–V curve fit, using the following form of the Boltzmann equation: G/Gmax = 1/(1+exp((− (Vm−V0.5)/Ka))).

For CDI characterization, (ICa/IBa) to time relations were generated as follows. Normalized traces of the sampled oocytes were separately averaged for either Ba2+ or Ca2+ measured currents producing an average and SEM for each timed sampling point (many of the measurements include Ba2+ and Ca2+ traces produced from the same oocyte). The (ICa/IBa) value for each time point was computed by the division of the above averages. SEM of the (ICa/IBa) ratio was computed using the root mean square of the following relation (Taylor, 1982; Bock and Regler, 1990): (SEMICa/IBa)2 = ((SEMBa/IBa)2 + (SEMCa/ICa)2) × (ICa/IBa)2, where IBa and ICa are the averaged time point Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents and SEMBa, SEMCa are the averaged IBa and ICa SEMs. Graphs and statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot (Systat Software). Comparison between a single test group and the control was calculated using an unpaired t test while comparison between several groups was done using one-way ANOVA (Holm–Sidak test).

CD spectroscopy.

Measurements were performed using a Chirascan CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics). Cuvette path length was 0.1 mm and sample concentrations were 200 μm. Protein buffer contained 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 0.2 m NaCl, and concentrations of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE). The purity and monodispersity of all samples were checked by SDS-PAGE with Tris-Tricine gels and analytical size-exclusion chromatography. Each spectrum was averaged from four repeated scans, ranging between 180 and 300 nm at a scan rate of 1.25 nm/s. Raw data were corrected by subtracting the contribution of the buffer to the signal. Subtracted data were then smoothed and converted to mean residue molar ellipticity units. α-helical content of sampled proteins (% α-helix) was extracted from mean residue molar ellipticity values at 222 nm as described previously (Greenfield and Hitchcock-DeGregori, 1993). All measurements were repeated at least twice.

Results

Structural analysis of the I–II linker/CaVβ2 complexes

Earlier structural studies of the AID/CaVβ complex provided important insights into the CaVβ architecture and its interactions with the α1 anchoring sequence (Chen et al., 2004; Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004). Those results also suggested that the PL might take a helical conformation. To date, a PL helical conformation was suggested by bioinformatics and CD spectroscopy of a CaV2.2-based PL synthetic peptide (Arias et al., 2005). To further test this hypothesis and explore structural determinants of the I–II linker, we coexpressed, purified, and crystallized the CaVβ2 functional core with the I–II linker fragment of either CaV1.2 or CaV2.2 pore forming subunits (Fig. 1B). The CaV1.2 I–II linker/CaVβ crystal structure was determined by SAD at 2.0 Å resolution, using halide soaked crystals. The refined model comprises residues 449–477 of the CaV1.2 I–II linker and residues 35–137, 218–274, and 294–414 of CaVβ2 (Fig. 1C,E). We solved the structure of the CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 complex, using SIRAS to 1.95-Å resolution. This model includes residues 363–407 of the CaV2.2 I–II linker and residues 36–141, 218–281, and 295–413 of CaVβ2 (Fig. 1D,E). The crystallographic statistics are shown in Table 1. Rfree values for the CaV1.2 I–II linker/ CaVβ2 and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 are 22.9% and 23.8%, respectively.

In both structures, the relative orientation is preserved between the two CaVβ domains. The CaVβ GuK domain is the most similar region (RMSD = 0.31 Å for 149 Cα atoms). A small structural subdomain, which replaces the mononucleoside subdomain defined by the first to third short helices of the GuK, referred to as the “ear lobe” (Opatowsky et al., 2004), lacks electron density in both structures. The SH3 domain is also similar between both structures (RMSD = 0.44 Å for 80 Cα atoms). Helix α2 is slightly tilted between structures (Fig. 1C,D). The variability in this α-helix angle relative to the core of the SH3 domain in different β structures demonstrates its flexibility.

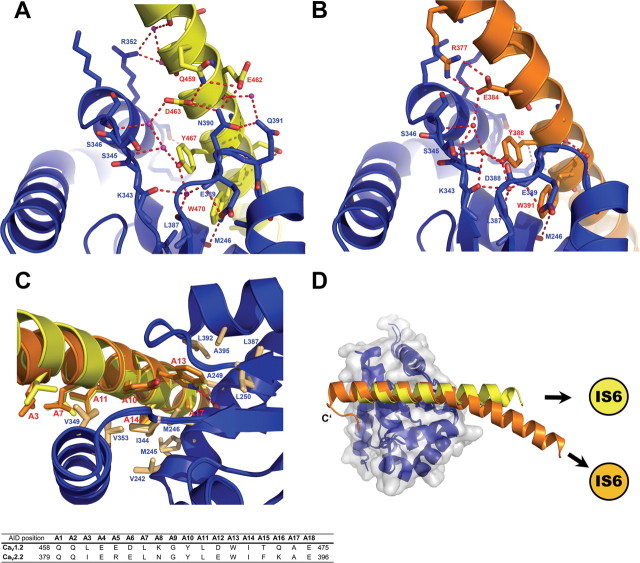

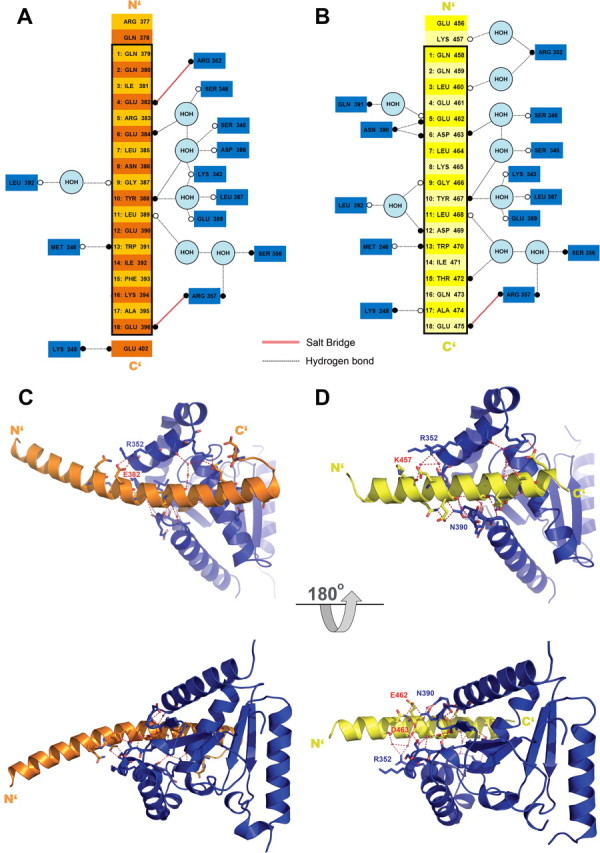

The main I–II linker/CaVβ interaction in both CaV1.2 and 2.2 is mediated through the GuK domain of CaVβ and the highly sequence-conserved AIDs of I–II linkers (Pragnell et al., 1994) (Figs. 1A,E, 2). In general, the high affinity AID/CaVβ interface is structurally conserved where AID takes an α-helical conformation and interacts with the AID binding pocket (ABP) by myriad nonpolar and polar interactions. We now observe the structural origin of this conservation by comparing AIDs from three different channels, CaV1.1 (Opatowsky et al., 2004), 1.2, and 2.2, in complex with CaVβ2. Figure 2 illustrates the conservation of the AID/ABP interface of the two current complex structures. The structures also point to some isoform-specific properties of the I–II linker/CaVβ interfaces. In CaV1.2, the visible PL is a straight continuation of the AID α-helix. On the other hand, this region of the CaV2.2 I–II linker is bent relative to the AID region (Fig. 2D). This curvature is supported by a specific subtype side-chain interaction pattern (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

The AID/CaVβ interface is structurally conserved between CaV1.2 and CaV2.2. A, B, Important polar interactions are conserved between the CaV1.2 (A, yellow) and CaV2.2 (B, orange) I–II linker/CaVβ interfaces. The GuK domain of CaVβ is blue. Important interface residues appear as sticks. C, Superposition of the AID/CaVβ interfaces of the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 crystal structures. Note the conserved position of many nonpolar residues (sticks) important for the interaction from both AID and Cavβ. D, Top view of the superposition of CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II linker/CaVβ2 complexes.

Figure 3.

The CaVβ/AID interface—polar contacts. A, B, A schematic illustration of the polar contacts of the CaVβ/AID interface as observed in the CaV2.2 (A) and CaV1.2 (B) I–II linker/CaVβ2 crystal structures. Schemes represent a perspective of the ABP/AID interaction network using the orientation of C and D (top), rotated 90° counterclockwise. CaVβ residues appear as blue boxes. Residues of the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II linkers are yellow and orange, respectively. Open and closed circles denote backbone and side-chain moieties, respectively. The AID region is framed in black. The numbers appearing before AID residues point to their relative position in the AID positions listed in the table of Figure 2C. C, D, α-helix curvature of CaV2.2 I–II linker and the variation in the polar contacts of its interface. Top (up) and bottom (down) views of the CaV2.2 (C) and CaV1.2 (D) I–II linker/ CaVβ2 interface. In the CaV1.2 complex (D), the N-terminal AID region interacts with helix α6 (R352) of β by water-mediated hydrogen bonds between the backbone carbonyls of CaV1.2 K457 and L460. Hydrogen bonds between β N390 and the I–II linker E462 and D463 support interaction with the other side of the AID. In contrast, in the CaV2.2 complex (C), due to sequence differences, no such interaction is observed with N390 of β. In addition, instead of water-mediated hydrogen bonds, polar interactions are observed between β residue R352 and the AID N terminus E382, allowing closer packing and supporting the curvature of the CaV2.2 I–II linker.

CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 I–II proximal linkers are not structurally identical

The I–II linker α-helical AID regions are clearly observed in both crystal structures. Nevertheless, only 28% of the CaV1.2 and 39% of the CaV2.2 protein could be modeled into electron density (Fig. 1E). The CaV1.2 I–II linker lacks density for 13 aa from its N-terminal end and has no density C-terminal to the AID region (Fig. 1C). The CaV2.2 I–II linker extends as a continuous α-helix upstream of the AID almost to its N-terminal end (Fig. 1D). This isoform also shows density downstream to the AID sequence in a form of a short loop bending the linker back in the direction of the N terminus, but following this loop the density disappears. Since interpretable diffraction data are generated only from stable and conformationally homogeneous regions of the crystallized molecule, this lack of electron density is most simply explained by high flexibility and static disorder.

Working models for VDCC regulation by CaVβ presume the PL to adopt a continuous α-helical conformation, following the AID/CaVβ interaction (Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004; Arias et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008; Findeisen and Minor, 2009). In these models, the PL, serving as a rigid α-helical rod, transduces the binding of CaVβ to movement of IS6 and in turn, to changes in the channel pore. In the CaV2.2 I–II linker structure, the proximal linker region is indeed mostly α-helical. The PL-AID region appears as a single 40-aa-long α-helix bound to the GuK domain of CaVβ at its C terminus (AID). On the other hand, the CaV1.2 PL α-helix, contrary to the working models, is much shorter and breaks at a glycine residue (G449) closer to the AID (Figs. 1C,E, 2D). This variation is most intriguing since a PL stable α-helical conformation is presumably crucial for VDCC function.

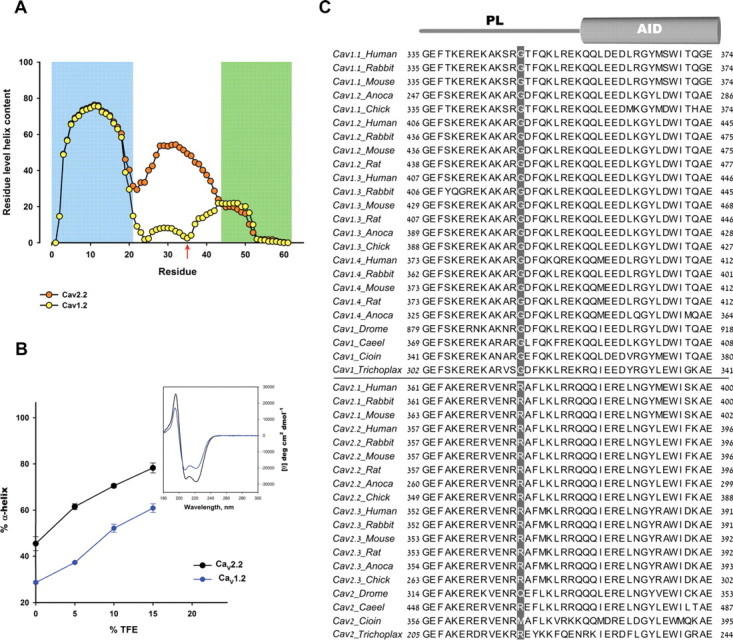

The CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 PL protein sequences are similar (Fig. 1E). However, on closer examination by a helical behavior prediction algorithm (Muñoz and Serrano, 1997), the predicted α-helical content of CaV2.2 PL was significantly higher than that of CaV1.2 (Fig. 4A), consistent with the crystallographic observations. To further compare the secondary structure of the PLs of these channels experimentally and corroborate the crystal structures, we used CD spectroscopy. Arias et al. (2005) have previously shown the high helical content of an isolated peptide representing the CaV2.2 PL, using this method. Although CD spectroscopy is a low resolution structural method, it enables convenient measurement of the degree of α-helical structure in solution. In the intact α1 subunit, the PL region is flanked by known α-helical structures (Fig. 1A). To assess the α-helical propensity of proximal linkers in a more native conformational environment, PL-AID regions of the I–II linkers were expressed downstream of an 18 residue, high helix-propensity sequence [3×AAKAAE (Baldwin, 1995)] (Fig. 1B). In these experiments, increasing TFE, a helix-stabilizing solvent (Hamada et al., 1995), was added to compensate for the lack of CaVβ and mimic the more hydrophobic conditions formed by its interaction with the AID. As presented in Figure 4B, the Helix-CaV1.2 PL-AID protein α-helical content was significantly lower than that observed for Helix-CaV2.2 PL-AID. This difference was preserved with the addition of TFE. Thus, the CD data correlates with the crystallographic observations.

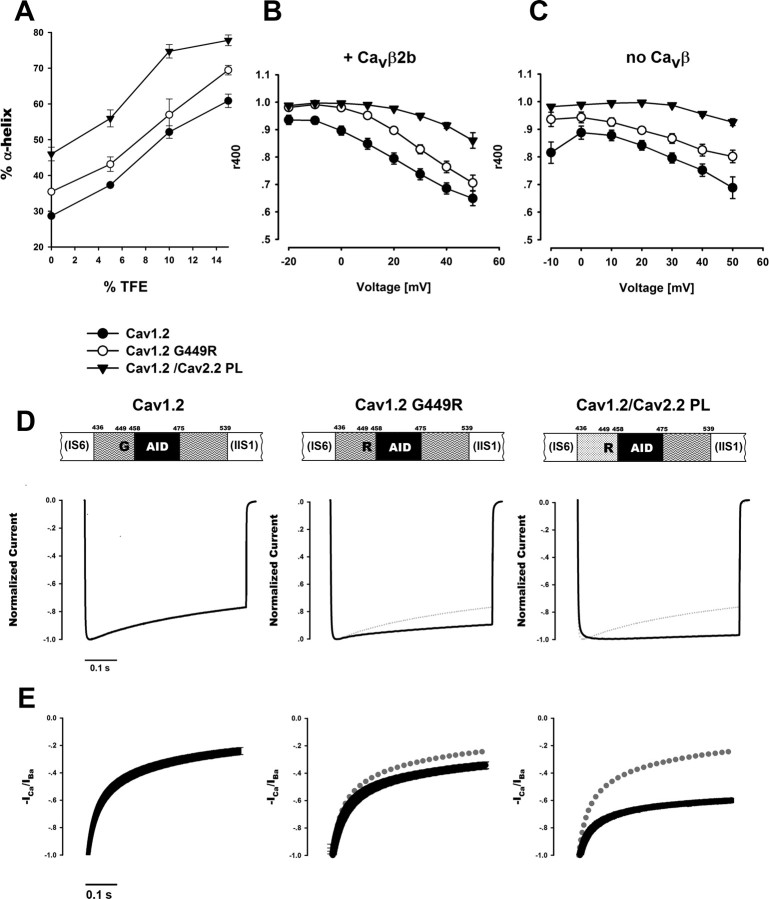

Figure 4.

The CaV1 and CaV2 PLs are not structurally identical. A, Helical content per residue predicted by AGADIR (Muñoz and Serrano, 1997) for the Helix-CaV1.2 PL-AID (yellow) and for Helix-CaV2.2 PL-AID (orange) proteins. Red arrow denotes the CaV1.2 G449/CaV2.2 R370 position. Total Agadir scores were 26.38 for Helix-CaV1.2 PL-AID and 40.11 for Helix-CaV2.2 PL-AID using default parameters. B, α-helical content of CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 Helix-PL-AID proteins at increasing TFE concentrations as measured by CD spectroscopy. Error bars represent SEM. Inset shows representative CD spectra of the CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 Helix-PL-AID proteins (200 μm, 10% TFE). Significantly higher α-helix content for CaV2.2 PL is observed by its higher signal at 222 nm. Although constructs have different but highly homologous AIDs, the PL presents the majority of conformational change between them; compare Figures 5A and 6A wild types versus chimeras. C, Multiple sequence alignment of PL-AID regions for a variety of CaV α1 orthologs and paralogs. Highlighted is the CaV1.2 α-helix-breaking glycine (G449 in Rabbit CaV1.2) position, conserved only in CaV1 channels. The homologous position in CaV2 channels is mostly arginine (all mammalians) or another high α-helix propensity residue. Figure was prepared using JALVIEW (Waterhouse et al., 2009).

The CD spectra show that the PL region may encode some degree of conformational flexibility, depending on channel subtype, suggesting that the working models were too general. The sequence differences between CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 PLs should encode the conformational difference between them. In a multiple sequence alignment between sequences of a wide range of high voltage activated VDCC α1 PLs, such a distinction is observed. Glycine 449 (rabbit CaV1.2), the residue where the PL helix breaks in the crystal structure, is conserved between all CaV1 channels (Fig. 4C). Glycine residues are unique in their lack of side-chain steric interference, permitting a higher flexibility to protein structures (O'Neil and DeGrado, 1990; Creamer and Rose, 1994; Pace and Scholtz, 1998). The homologous position to this glycine in CaV2 channels is generally arginine (all mammalians) or another high α-helix propensity residue. The partition of CaV1 and CaV2 channels, as based on the PL and especially G449, extends even to the very primitive multicellular metazoan, Trichoplax adhaerens. Due to the correlation with structural evidence, this position was subjected to functional mutational analyses to test whether the observed structural feature indeed has functional consequences.

Extension of the CaV1.2 PL α-helical structure decelerates VDI

To examine the implication of the PL conformational differences on channel function, we recorded currents of structure-based channel mutations expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The consequences of extending the CaV1.2 α-helix conformation were examined by mutating the conserved CaV1.2 PL G449 to arginine as appears in the homologous position in CaV2 (Figs. 1E, 4C). In addition, a chimera was prepared wherein the whole CaV1.2 PL was replaced with that of CaV2.2 (CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL). Not surprisingly, the arginine substitution increased the PL helix propensity of CaV1.2 G449R, as assessed by CD spectroscopy (Fig. 5A). The CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL chimera had even higher helix content.

Figure 5.

Extension of the PL α-helix decelerates CaV1.2 inactivation. A, CD measurements of α-helical content for CaV1.2 Helix-PL-AID proteins at increasing TFE. α-helical content increases in the G449R mutant and more so when PL is replaced to that of CaV2.2. B, C, Voltage dependence of CaV1.2 Ba2+ current inactivation kinetics shown with (B) or without (C) CaVβ2b. r400 denotes the residual current at 400 ms from depolarization normalized to peak current. Inactivation is slower for the α-helix favoring mutations. Average values and SEM are plotted. Statistics at +20 mV or +30 mV without CaVβ are presented in Table 2. D, Representative Ba2+ currents of WT CaV1.2, CaV1.2 G449R and CaV1.2 /CaV2.2 PL chimera. Currents were recorded during a depolarizing step from a holding potential of −80 mV. Traces of highest current to depolarization voltage (+20, +20, and +10 mV, respectively) are presented normalized to their peak value. Dotted trace denotes the CaV1.2 WT current for comparison. E, Normalized −ICa/IBa of averaged currents at +20 mV depolarization. Average values and SEM are plotted. When comparing −ICa/IBa values at 400 ms from depolarization, all measured constructs show significant difference in CDI values. (CaV1.2 G449R: p = 0.005 vs WT, p < 0.001 vs others; CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL, p < 0.001 vs all others; one-way ANOVA).

Both mutant channels displayed robust inward Ba2+ currents comparable to WT CaV1.2 when expressed with CaVβ2b. As shown in Figure 5, B and D, CaV1.2 G449R displayed slower inactivation kinetics than the CaV1.2 WT. Likewise, CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL inactivation was even slower. These results demonstrate the importance of the conformation of the PL region for CaV1.2 inactivation kinetics and specifically show that increasing the PL helix propensity results in deceleration of VDI for CaV1. These results are also consistent with the converse findings of Findeisen and Minor (2009), who showed that α-helix destabilizing polyglycine substitution mutations in the CaV1.2 PL accelerated VDI.

As both α1 PL and CaVβ are physically coupled and impact channel activity, we then asked what the PL conformational effects of our mutations are when measured by oocytes injected with α1 and α2δ RNA alone. Xenopus oocytes are known to endogenously express small amounts of CaVβ3, capable of acting upon recombinantly expressed VDCCs. These endogenous proteins are critical for the membrane transport of expressed α1 genes in the absence of exogenously added CaVβ (Tareilus et al., 1997). However, VDCC currents are unaffected by these endogenous CaVβs (Zhang et al., 2008), since in the steady state, their effective concentration is too low for binding the abundant plasma membrane localized channels (He et al., 2007). In all our experiments, the absence of CaVβ at the plasma membrane was apparent by the slower channel expression and lower current amplitudes measured. In addition, for all measured currents, the voltage dependence of activation was relatively depolarized, as expected by the lack of hyperpolarizing shift induced by CaVβ (Table 2). As shown in Figure 5, B and C, the effect of CaV1.2 G449R, as that of CaV1.2/CaV1.2 PL, on inactivation kinetics were similar with or without CaVβ2b. Thus, CaVβ is not required for the effect of PL structure on CaV1.2 inactivation kinetics.

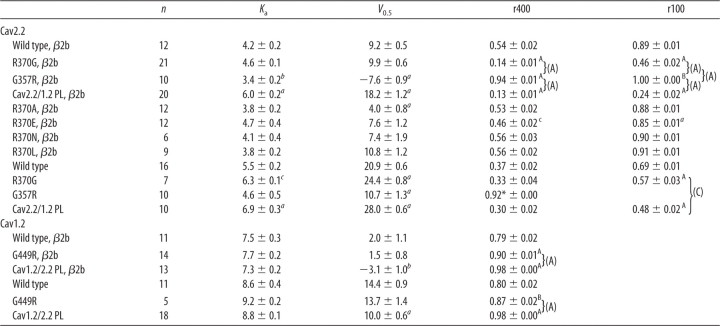

Table 2.

Ba2+ current electrophysiological properties

G–V relation voltage for 50% activation (V0.5) and slope factor (Ka) were calculated from voltage current relations as described in Materials and Methods. r400 and r100 for traces at +20 mV (or 30 mV when CaVβ is absent). Values are presented as mean ± SEM, the number of oocytes appears under “n.”

ap ≤ 0.001, bp ≤ 0.01, cp ≤ 0.05 compared with the corresponding WT (unpaired t test); * indicates that r4900 value is presented instead.

A(p ≤ 0.001), B(p ≤ 0.01), C(p ≤ 0.05) compared with the corresponding WT, (A) (p ≤ 0.001), (B) (p ≤ 0.01), (C) (p ≤ 0.05) (one-way ANOVA).

Extension of the CaV1.2 PL α-helical structure decelerates CDI

CaV1 channel inactivation is thought to take place through two separate but parallel mechanisms, CDI and VDI (Lee et al., 1985; Budde et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2004; Cens et al., 2006). Following the observation that extension of the CaV1.2 PL α-helix decelerates VDI, we also investigated its effect on CDI. When Ca2+ is the permeable ion as in physiological conditions, both CDI and VDI take place. On the other hand, when Ca2+ is replaced with Ba2+, only VDI occurs. The combined analysis of Ba2+ versus Ca2+ currents is thus traditionally used to quantify the isolated effect of CDI (Zühlke and Reuter, 1998; Peterson et al., 1999, 2000; Liang et al., 2003; Mori et al., 2004). Barrett and Tsien (2008), treating VDI and CDI as processes with independent probabilities, suggested using the ratio of normalized (ICa/IBa) to provide a measure of CDI, especially in cases where changes in VDI are observed. We have used this method. As shown in Figure 5E, a small but significant reduction in CDI was observed for the CaV1.2 G449R mutant. A more significant reduction was observed for the CaV1.2/2.2 PL chimera. Together, these data suggest that extension of the CaV1.2 PL α-helix decelerates both CDI and VDI.

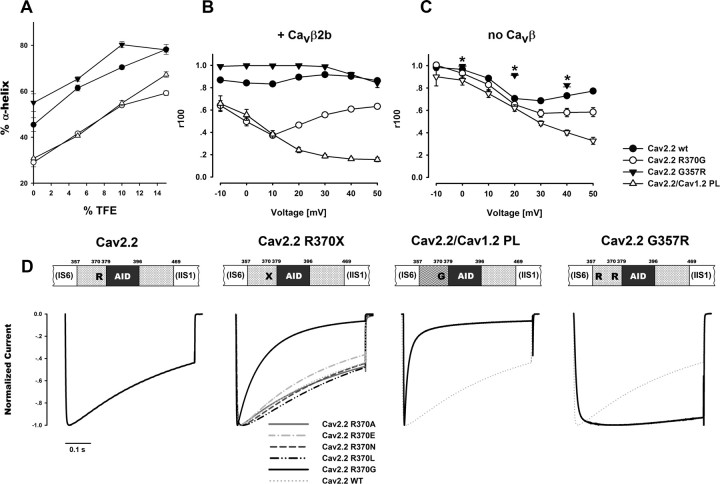

Perturbation of CaV2.2 PL α-helical structure accelerates VDI

Based on the observed effect of the PL conformation on CaV1.2 inactivation, we further extended our investigation to the CaV2.2 channel. As the crystal structure reveals, the PL of this channel isoform is almost a complete, continuous α-helix. We therefore explored the functional consequences of perturbing this α-helical structure. Based on the PL multiple sequence alignment (Fig. 4C), we chose rabbit CaV2.2 R370, conserved in CaV2 and in the homologous position to CaV1.2 G449 as a target for our mutational analyses. As illustrated by Figure 6, B and D, the R370G mutant displayed substantially faster Ba2+ current inactivation kinetics than the CaV2.2 WT channel. On the other hand, mutants R370E, R370L, R370N, or R370A, all coexpressed with CaVβ2b, did not. In addition to a small acceleration in R370E, these mutants were indistinguishable from CaV2.2 WT. Given the results for these five substitutions, we could rule out the importance of side-chain size, hydrophobicity, or charge as factors in the marked effect R370G has upon inactivation kinetics. In the CD assay, the Helix-CaV2.2 R370G PL-AID protein presented a reduction in its α-helix content relative to the WT CaV2.2 (Fig. 6A). We therefore conclude that the destabilizing effect of glycine on the CaV2.2 PL α-helix is the most probable cause for the acceleration of inactivation kinetics.

Figure 6.

Perturbation of the CaV2.2 PL helical structure accelerates VDI. A, CD measurements of α-helical content for CaV2.2 Helix-PL-AID proteins at increasing TFE. CaV2.2 Helix-PL-AID α-helix is destabilized by R370G and when its PL is replaced by that of CaV1.2 but further stabilized when G357 is mutated to arginine. B, C, Voltage dependence of CaV2.2 Ba2+ current inactivation kinetics is shown with (B) or without (C) CaVβ2b. Inactivation is presented as the residual current at 100 ms from depolarization (r100). For the G357R mutant without CaVβ, residual currents at 4900 ms from depolarization are plotted (r4900, asterisks). Since G357R residual current, even at 4900 ms from depolarization, is substantially less than WT at 100 ms, its inactivation is necessarily slower. Average values and SEM are plotted. Statistics at +20 mV (or +30 mV without CaVβ) are presented in Table 2. D, Representative Ba2+ currents of WT CaV2.2, CaV2.2 mutants at positions R370, CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL chimera, and G357R. Currents were recorded during a depolarizing step from a holding potential of −80 mV. Traces of highest current to depolarization voltage (+20, +20, +30 mV, 0 mV, respectively) are presented normalized to their peak value. Dotted trace denotes the CaV2.2 WT current for comparison.

The CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL chimera sequence comprises that of R370G along with nine additional substitutions, seven of which are chemically different residues (Fig. 1E). Relative to the point mutant, this chimeric channel has a comparable disruption of its PL α-helix (Fig. 6A). Ba2+ currents from these CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL channels demonstrated an extremely fast inactivation rate (Fig. 6B,D). These results indicate that the perturbation of the PL α-helix contributes to accelerated inactivation in CaV2.2.

As observed in Figure 6C, the effects of PL α-helix destabilizing mutations on inactivation kinetics persist in the absence of CaVβ, leading us to conclude that they are also CaVβ independent. However, in the presence of CaVβ, the effects of the mutations are potentiated and modified (Fig. 6, compare B,C). These structural perturbations probably alter the mechanical transduction of CaVβ binding to the channel pore. This change in Cavβ effect occurs in conjunction with the intrinsic effect of the PL conformation, accounting for the more pronounced differences between mutants in the presence of CaVβ2b relative to its absence.

Interestingly, the inactivation observed for WT CaV2.2 with CaVβ2b Ba2+ currents did not become faster at higher depolarization potentials, as observed for CaV1.2. Instead, a relative increase in r100 is observed at voltages higher than +10 mV of the r100/voltage relation (Fig. 6C). This phenomenon was previously reported in CaV2.2 studies but its origin is not completely understood (Fox et al., 1987; Jones and Marks, 1989; Patil et al., 1998; Wakamori et al., 1998; Wakamori et al., 1999; Kang et al., 2001; Meuth et al., 2002; Tselnicker et al., 2010). Furthermore, our PL mutations seem to affect this behavior and replacing the PL (CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL) seems to have eliminated it (Fig. 6C).

We saw that disrupting the PL accelerates CaV2.2 VDI, but would stabilizing it further obtain the opposite result? To address this question, we constructed a CaV2.2 mutant bearing a glycine to arginine substitution at the N-terminal G357 of the PL. The G357R mutation significantly increases the CaV2.2 PL helical content (Fig. 6A). Indeed, as observed in Figure 6, B and D, CaV2.2 G357R displayed extremely slow kinetics, uncharacteristic for CaV2.2. As in the other CaV2.2 mutations, the effect of G357R was not dependent on the presence of CaVβ. In the absence of the VDI-accelerating effect of CaVβ2b, the mutation effect of on current kinetics was even more pronounced and resulted in channels with extremely slow macroscopic inactivation kinetics (Fig. 6C).

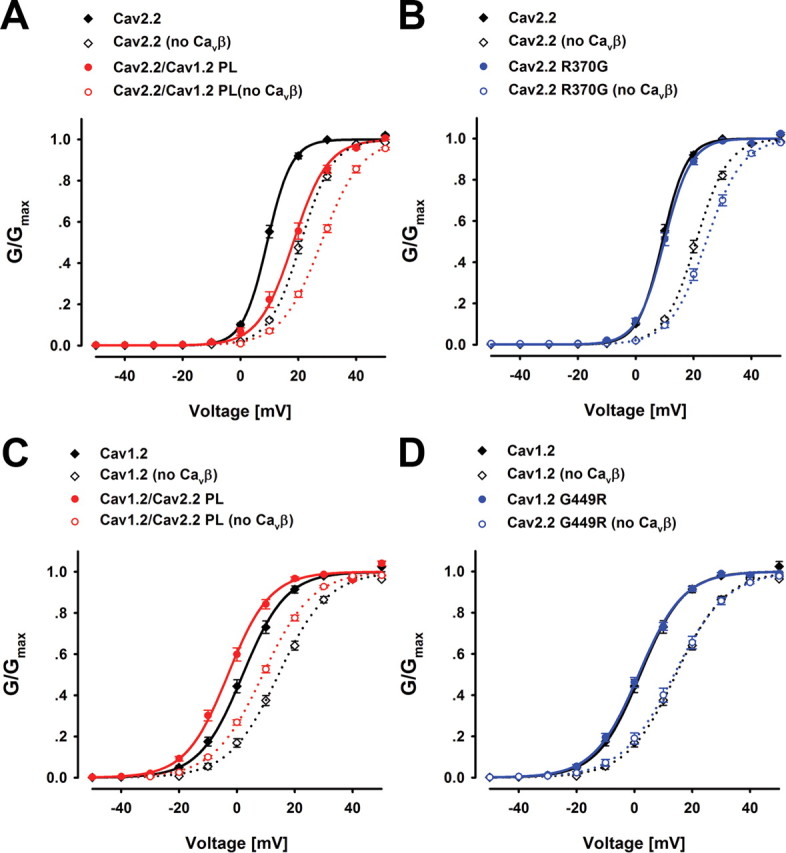

PL conformational effects on the voltage dependence of activation

While previous studies demonstrated the effect of the PL and CaVβ on inactivation kinetics, we reasoned that the same constraints attributed to these structural elements might modulate channel activation. Hence, we analyzed our electrophysiology records for this possibility. Both PL chimeras displayed shifts in their voltage dependence of activation relative to the respective background channel but in opposite directions. While the CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL midpoint of activation was depolarized relative to the CaV2.2 WT, the CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL activation was hyperpolarized relative to CaV1.2 WT (Table 2, Fig. 7A,C). For both the CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL and the CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL chimeras, this shift was not dependent on the presence of CaVβ (Fig. 7A,C). The CaVβ effect on V0.5 (i.e., hyperpolarization) of the activation curves was additive to the effect of the mutations. These results support our hypothesis that the PL regions of both CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 are also important factors in VDCC voltage-dependent activation.

Figure 7.

The effect of PL conformation on the voltage dependence of activation. A–D, Voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL (n = 20/10 +/−CaVβ) (A), CaV2.2 R370G (n = 21/7) (B), CaV1.2/CaV2.2 PL (n = 13/10) (C) and CaV1.2 G449R (n = 14/5) (D), relative to their respective wild types in the presence or absence of CaVβ2b.

A small depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation was observed for the point mutant CaV2.2 R370G relative to the CaV2.2 WT, only in the absence of CaVβ (Fig. 7B), while no significant shift was observed for CaV1.2 G449R (Fig. 7D). These mutations were shown to affect the PL helical content (Figs. 5A, 6A). However, possibly due to a smaller structural effect relative to the chimeras or other factors, their effect on the voltage dependence of activation is smaller or undetectable. This finding correlates with their milder effect on inactivation.

Discussion

The CaV1 and CaV2 proximal linkers are not structurally identical

The PL is located at the heart of a pivotal molecular junction in CaV1 and 2 channels, connected to both the β subunit and the channel gate. To date, a rigid α-helical PL region was posited as a requirement for the direct coupling of CaVβ modulation (Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004). Our findings highlight the importance of PL structure for channel function. However, they indicate that CaV1 and CaV2 PLs are not structurally identical, with consequences for functions like activation and inactivation properties.

In consonance with this functional significance, the CaV1 and CaV2 PL sequences are extremely conserved within subtypes (Fig. 4C). In fact, these protein regions have less sequence variability than their respective AID sequences. Changes in only few positions promote the conformational variation observed. The most critical variation seems to be Cav1.2 G449/Cav2.2 R370 at the fourteenth residue position of the PL. The identity of this residue can be used to partition VDCCs into subtypes, applicable for their entire molecular phylogeny.

In addition to the obvious change in secondary structure, the limited sequence variations between these two isoforms support multiple sequence-specific polar interactions possibly responsible for the different angle between CaVβ and the PL. That each conformation is driven by multiple sequence-specific polar interactions argues that the observed structures represent a genuine conformational variation between the CaV1 and CaV2 subtypes rather than the result of different crystal packing environments. Notably, residues 372–389 of CaV2.2, that include most of the sequence variations directing this conformational change, are known to be functionally important for Gβγ modulation (De Waard et al., 1997). Furthermore, it was shown previously that an intact α-helical PL is required for CaV2.1 regulation by Gβγ (Zhang et al., 2008). Thus, the low helical content of the CaV1 PL may be one of the reasons this regulation does not occur in this channel subtype.

The PL conformation has functional consequences in both subtype contexts

Our mutational analysis indicates that the respective native PL conformation largely affects inactivation kinetics. Perturbation of CaV2.2 PL α-helical structure (R370G) accelerates VDI kinetics. The large effect of a single glycine substitution as opposed to other substitutions strongly supports the conclusion that the observed effect originates, in part, from change in the secondary structure of the PL. In a complementary fashion, we show a similar effect occurs in CaV1.2, where extension of the PL α-helical structure of these channels clearly decelerates VDI. Previous results (Findeisen and Minor, 2009) show that perturbations to the CaV1.2 (and CaV2.1) PL by substitution to multiple glycines accelerate VDI. Thus, despite distinct channel subtypes with distinct functional characteristics, PL conformation seems to have a common role in both CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 inactivation. While PL secondary structure plays a major role it probably is not the exclusive one since the CaV2.2/CaV1.2 PL chimera exhibits even faster inactivation than CaV2.2 R370G despite an apparent identical helix propensity.

The PL structural module plays a significant role but is not the only factor in the inactivation mechanism. WT CaV2.2 channels naturally inactivate faster than WT CaV1.2. Inclusion of the more stable α-helical CaV2.2 PL in CaV1.2 slows and almost eliminates inactivation of these naturally slower inactivating channels. On the other hand, the faster inactivating CaV2.2 inactivates even faster with the CaV1.2 PL. Swapping this region between these channel isoforms does not exchange their inactivation tributes but rather influences their inactivation kinetics in their respective directions, depending to a large extent on the secondary structure of the PL introduced (Figs. 5A, 6A). Since the PL is directly coupled to the IS6 of the inner pore one can reasonably envisage its ability to directly affect the mobility of the IS6. The simplest explanation for these recorded effects is for the PL to affect inactivation through this TM α-helix. In some way, a change in the PLs architecture can be translated to a change in this mobility, which in turn affects the kinetics of channel closing during inactivation.

In our experiments with CaV1.2, changes introduced to the PL affected CDI in a similar direction as VDI. Considering the known role of the CaV1.2 C terminus/CaM complex in CDI (Zühlke and Reuter, 1998; Lee et al., 1999, 2000; Peterson et al., 1999; DeMaria et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2003), the observed changes in CDI by mutations of the PL imply a functional linkage between these two structural modules. Robust evidence for the physical interaction between these channel regions has not yet been presented. Nevertheless, a common role for the PL upon VDI and CDI can be explained if we assume their mechanisms share a common final step involving the mobility of the S6 segments of the channel.

The role of CaVβ

PL structural integrity is important for the mechanism of VDCC modulation by CaVβ. Specifically, other groups showed this modulatory linkage could be broken by multiglycine runs in the PL (Arias et al., 2005; Vitko et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Findeisen and Minor, 2009). In contrast, in all of our mutational findings, CaVβ modulation was not abolished as observed by effects on VDI kinetics (data not shown) and the shift in voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 7, Table 2). We suggest that our mutations were milder than the multiglycine changes, supported by the observation that the PL structure with the lowest helicity was that of WT CaV1.2. Furthermore, all mutations resulted in functional effects persistent also when CaVβ was absent. Hence, PL conformation appears to have two functional consequences, mediation of CaVβ modulation and intrinsic effects observable in the absence of CaVβ.

Our data are consistent with CaVβ promoting the α-helical structure of the PL (Opatowsky et al., 2004). As observed in the GV relations of our channel chimeras, our data exhibits similar trends with mutations that increase the PL helical propensity or the effect of CaVβ binding, i.e., a leftward shift. Similar trends were observed in a recent report where the first 70 I–II linker residues were interchanged between CaV1.2 and CaV2.3 (Gonzalez-Gutierrez et al., 2010). Nonetheless, the persistent effects of the PL mutations in the absence of CaVβ indicate that this region, independent of the binding of CaVβ, has helical secondary structure rather than random coil.

A new working model

As our data indicate, treating the PL as a rigid rod does not apply in all cases. In addition, the CaVβ independent effect exerted by the secondary structure of this region raises the possibility that instead of being only transducer of the CaVβ binding, this region has an intrinsic mechanistic role in the modulation of VDCC function. Assuming that inactivation involves the constriction of the inner pore, by a concerted movement of the four S6 segments (Hoshi et al., 1991; López-Barneo et al., 1993; Richmond et al., 1998; Spaetgens and Zamponi, 1999; Vilin et al., 1999; Findeisen and Minor, 2009), a possible unifying hypothesis may be to view the PL as part of a braking mechanism used to alter movement of one these helices (IS6) during inactivation, as posited for CaV3 channels (Arias-Olguín et al., 2008). Analogous to a shock absorber, such a mechanism involving the I–II linker/CaVβ complex can be illustrated as an effective spring directly coupled to this TM α-helix, which feedbacks a restrained resistance to its movement.

Controlling the PL conformation may be one way of evolution to “fine tune” VDCC inactivation kinetics. In CaV1.2, intrinsically slower inactivating channels, the PL is naturally less ordered. Further stabilizing this α-helix, as observed in our mutations, may completely eliminate inactivation creating malfunctioning channels, which could promote toxic cellular Ca2+ effects. CaV2.2 channels, on the other hand, are naturally faster inactivating channels. A “loosened” brake introduced into these channels allows extremely fast inactivation that might cause a premature termination of the Ca2+ signal.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant 1201/04 and a DIP-DFG Grant to J.A.H., L.A. was supported in part by a Dean's Excellence Scholarship. We thank Efrat Berman for assistance with subcloning, and Moshe Dessau, Reuven Wiener, and the staff at ESRF for help with diffraction data collection. Structure factors and atomic coordinates have been deposited with PDB codes 4DEY and 4DEX.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abrahams JP, Leslie AG. Methods used in the structure determination of bovine mitochondrial F1 ATPase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1996;52:30–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995008754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias JM, Murbartián J, Vitko I, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E. Transfer of beta subunit regulation from high to low voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3907–3912. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Olguín II, Vitko I, Fortuna M, Baumgart JP, Sokolova S, Shumilin IA, Van Deusen A, Soriano-García M, Gomora JC, Perez-Reyes E. Characterization of the gating brake in the I–II loop of Ca(v)3.2 T-type Ca(2+) channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8136–8144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708761200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin RL. Alpha-helix formation by peptides of defined sequence. Biophys Chem. 1995;55:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(94)00146-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Tsien RW. The Timothy syndrome mutation differentially affects voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 l-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710501105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock RK, Regler M. Data analysis techniques for high-energy physics experiments. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge UP; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde T, Meuth S, Pape HC. Calcium-dependent inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:873–883. doi: 10.1038/nrn959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Yang J. The beta subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cens T, Rousset M, Leyris JP, Fesquet P, Charnet P. Voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation in high voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;90:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Li MH, Zhang Y, He LL, Yamada Y, Fitzmaurice A, Shen Y, Zhang H, Tong L, Yang J. Structural basis of the alpha1-beta subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2004;429:675–680. doi: 10.1038/nature02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan KD, Zhang KY. Density modification for macromolecular phase improvement. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;72:245–270. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(99)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer TP, Rose GD. Alpha-helix-forming propensities in peptides and proteins. Proteins. 1994;19:85–97. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Liu H, Walker D, Scott VE, Gurnett CA, Campbell KP. Direct binding of G-protein betagamma complex to voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1997;385:446–450. doi: 10.1038/385446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen F, Minor DL., Jr Disruption of the IS6-AID linker affects voltage-gated calcium channel inactivation and facilitation. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:327–343. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. Kinetic and pharmacological properties distinguishing three types of calcium currents in chick sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1987;394:149–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Contreras G, Neely A, Hidalgo P. Swapping the I–II intracellular linker between l-type CaV1.2 and R-type CaV2.3 high-voltage gated calcium channels exchanges activation attributes. Channels. 2010;4:42–50. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.1.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield NJ, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Conformational intermediates in the folding of a coiled-coil model peptide of the N-terminus of tropomyosin and alpha alpha-tropomyosin. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1263–1273. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haebel PW, Wichman S, Goldstone D, Metcalf P. Crystallization and initial crystallographic analysis of the disulfide bond isomerase DsbC in complex with the alpha domain of the electron transporter DsbD. J Struct Biol. 2001;136:162–166. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada D, Kuroda Y, Tanaka T, Goto Y. High helical propensity of the peptide fragments derived from beta-lactoglobulin, a predominantly beta-sheet protein. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:737–746. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He LL, Zhang Y, Chen YH, Yamada Y, Yang J. Functional modularity of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biophys J. 2007;93:834–845. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 1991;7:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SW. Overview of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1998;30:299–312. doi: 10.1023/a:1021977304001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SW, Marks TN. Calcium currents in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. I. Activation kinetics and pharmacology. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:151–167. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MG, Chen CC, Felix R, Letts VA, Frankel WN, Mori Y, Campbell KP. Biochemical and biophysical evidence for gamma 2 subunit association with neuronal voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32917–32924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Ghosh S, Nunziato DA, Pitt GS. Identification of the components controlling inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:745–754. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Wong ST, Gallagher D, Li B, Storm DR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to and modulates P/Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:155–159. doi: 10.1038/20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation and inactivation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Marban E, Tsien RW. Inactivation of calcium channels in mammalian heart cells: joint dependence on membrane potential and intracellular calcium. J Physiol. 1985;364:395–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, DeMaria CD, Erickson MG, Mori MX, Alseikhan BA, Yue DT. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron. 2003;39:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors Channels. 1993;1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusty CJ. A gentle vapor-diffusion technique for cross-linking of protein crystals for cryocrystallography. J Appl Cryst. 1999;32:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A. Crystallization of biological macromolecules. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meuth S, Pape HC, Budde T. Modulation of Ca2+ currents in rat thalamocortical relay neurons by activity and phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1603–1614. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MX, Erickson MG, Yue DT. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 2004;304:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1093490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CS, Haupt A, Bildl W, Schindler J, Knaus HG, Meissner M, Rammner B, Striessnig J, Flockerzi V, Fakler B, Schulte U. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14950–14957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz V, Serrano L. Development of the multiple sequence approximation within the AGADIR model of alpha-helix formation: comparison with Zimm-Bragg and Lifson-Roig formalisms. Biopolymers. 1997;41:495–509. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19970415)41:5<495::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil KT, DeGrado WF. A thermodynamic scale for the helix-forming tendencies of the commonly occurring amino acids. Science. 1990;250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opatowsky Y, Chomsky-Hecht O, Kang MG, Campbell KP, Hirsch JA. The voltage-dependent calcium channel beta subunit contains two stable interacting domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52323–52332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opatowsky Y, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Hirsch JA. Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta subunit functional core and its complex with the alpha 1 interaction domain. Neuron. 2004;42:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace CN, Scholtz JM. A helix propensity scale based on experimental studies of peptides and proteins. Biophys J. 1998;75:422–427. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(98)77529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil PG, Brody DL, Yue DT. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of l-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, Lee JS, Mulle JG, Wang Y, de Leon M, Yue DT. Critical determinants of Ca(2+)-dependent inactivation within an EF-hand motif of l-type Ca(2+) channels. Biophys J. 2000;78:1906–1920. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I–II cytoplasmic linker of the alpha 1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Featherstone DE, Hartmann HA, Ruben PC. Slow inactivation in human cardiac sodium channels. Biophys J. 1998;74:2945–2952. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shistik E, Ivanina T, Blumenstein Y, Dascal N. Crucial role of N terminus in function of cardiac l-type Ca2+ channel and its modulation by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17901–17909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaetgens RL, Zamponi GW. Multiple structural domains contribute to voltage-dependent inactivation of rat brain alpha(1E) calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22428–22436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR. An introduction to error analysis: the study of uncertainties in physical measurements. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tselnicker I, Tsemakhovich VA, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Stargazin modulates neuronal voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channel Ca(v)2.2 by a Gbetagamma-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20462–20471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F, Clark KA, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel beta-subunit and an alpha-subunit domain. Nature. 2004;429:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature02588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilin YY, Makita N, George AL, Jr, Ruben PC. Structural determinants of slow inactivation in human cardiac and skeletal muscle sodium channels. Biophys J. 1999;77:1384–1393. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76987-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitko I, Shcheglovitov A, Baumgart JP, Arias-Olguín II, Murbartián J, Arias JM, Perez-Reyes E. Orientation of the calcium channel beta relative to the alpha(1)2.2 subunit is critical for its regulation of channel activity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Strobeck M, Niidome T, Teramoto T, Imoto K, Mori Y. Functional characterization of ion permeation pathway in the N-type Ca2+ channel. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:622–634. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Mikala G, Mori Y. Auxiliary subunits operate as a molecular switch in determining gating behaviour of the unitary N-type Ca2+ channel current in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1999;517:659–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0659s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen YH, Bangaru SD, He L, Abele K, Tanabe S, Kozasa T, Yang J. Origin of the voltage dependence of G-protein regulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14176–14188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1350-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zühlke RD, Reuter H. Ca2+-sensitive inactivation of l-type Ca2+ channels depends on multiple cytoplasmic amino acid sequences of the alpha1C subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3287–3294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]