ABSTRACT

Postnatal alveolar formation is the most important and the least understood phase of lung development. Alveolar pathologies are prominent in neonatal and adult lung diseases. The mechanisms of alveologenesis remain largely unknown. We inactivated Pdgfra postnatally in secondary crest myofibroblasts (SCMF), a subpopulation of lung mesenchymal cells. Lack of Pdgfra arrested alveologenesis akin to bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a neonatal chronic lung disease. The transcriptome of mutant SCMF revealed 1808 altered genes encoding transcription factors, signaling and extracellular matrix molecules. Elastin mRNA was reduced, and its distribution was abnormal. Absence of Pdgfra disrupted expression of elastogenic genes, including members of the Lox, Fbn and Fbln families. Expression of EGF family members increased when Tgfb1 was repressed in mouse. Similar, but not identical, results were found in human BPD lung samples. In vitro, blocking PDGF signaling decreased elastogenic gene expression associated with increased Egf and decreased Tgfb family mRNAs. The effect was reversible by inhibiting EGF or activating TGFβ signaling. These observations demonstrate the previously unappreciated postnatal role of PDGFA/PDGFRα in controlling elastogenic gene expression via a secondary tier of signaling networks composed of EGF and TGFβ.

KEY WORDS: Pdgfra, Alveolar formation, Elastogenesis, Lung development, Secondary crest myofibroblast, Mouse, Human

Summary: A cell-targeted genetic approach has revealed a previously unrecognized role of the PDGFA/PDGFRa axis, mediated through a complex and interdependent cross regulatory network of multiple signaling pathways that converge to regulate postnatal alveologenesis.

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian lung is an efficient gas exchange organ. This capability is owed to the vast surface area, generated during postnatal development by a process known as alveolar formation or alveologenesis. At completion, alveologenesis in human lungs produces millions of alveoli, expanding the functional gas exchange surface area to nearly 100 m2. Perturbations in development or destruction of alveoli are causative or associative of a wide spectrum of both neonatal and adult human pulmonary diseases (Husain et al., 1998; Boucherat et al., 2016).

Alveologenesis in humans occurs mostly, and in mice entirely, postnatally. In contrast to the many key regulators of early lung morphogenesis (i.e. branching morphogenesis), the identity and the mechanisms of action of various molecules in postnatal lung development, and assembly of alveoli remain largely unknown. Alveologenesis requires the formation of structures known as ‘secondary crests’. These comprise cells with distinct lineage histories, including a highly specialized mesodermal cell type known as the secondary crest myofibroblast (SCMF, also known as alveolar myofibroblast). SCMFs are initially PDGFRαpos, but late in embryonic development become αSMApos and are found localized at the tip of the alveolar septa in close proximity to deposits of elastin (ELN). Until recently, SCMFs remained inaccessible to isolation and analysis. We, and others, have shown that SCMFs are a subclass of lung mesodermal cells that are targeted by hedgehog signaling, and thus can be tagged and isolated using Gli1-creERT2, a high-fidelity hedgehog reporter (Ahn and Joyner, 2004; Li et al., 2015; Kugler et al., 2017).

Platelet-derived growth factor is crucial for normal vertebrate development (Soriano, 1997). In lung morphogenesis, PDGFA, and its sole receptor PDGFRα, constitute an axis of cross-communication between endodermal and mesodermal cells (Boström et al., 1996). The ligand is expressed by endodermal cells (Boström et al., 1996) and PDGFRα is ubiquitously expressed throughout the lung mesoderm (Orr-Urtreger and Lonai, 1992). Recently, single cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) showed PDGFRαpos cells are made up of cell lineages that make distinct contributions to lung maturation and response to injury (Endale et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Homozygous deletion of Pdgfa results in alveolar hypoplasia and lethality at birth (Boström et al., 1996; Lindahl et al., 1997). Germline lack of PDGFRα is even more profoundly lethal and Pdgfra null mice die before embryonic day (E) 16 (Boström et al., 2002). Cell-targeted inactivation of Pdgfra in transgelin (SM22, also known as TAGLN)-expressing cells also leads to a phenotype of alveolar hypoplasia (McGowan and McCoy, 2014). In the latter studies, deletion of Pdgfa or Pdgfra caused extensive cell death, making it impossible to rule out the possibility that the alveolar phenotype is the consequence of cell death, rather than directly related to lack of PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling. In addition, the genetic approaches, using germline deletion or conditional inactivation of Pdgfa or Pdgfra, were not specific to the alveolar phase of lung development. Thus, the specific function of Pdgfra in postnatal alveologenesis, particularly in SCMF, the key mesodermal cell type in this process, has remained unclear.

In the present study, we utilized Gli1-creERT2 to generate conditional homozygous mice carrying a deletion of Pdgfra exons 1-4 in SCMF during postnatal lung development. This approach enabled us to examine the role of Pdgfra specifically during the process of alveologenesis and in a cell-targeted manner. The results illustrate a complex and interdependent cross-regulatory network, composed of multiple signaling pathways that converge to regulate normal elastogenesis in SCMF during postnatal development. Furthermore, the findings provide evidence for the potential nature and the mechanism of ELN fiber defects observed in various human alveolar pathologies, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).

RESULTS

Postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra in SCMF

To examine the role of PDGFA/PDGFRα in SCMF during postnatal alveologenesis, we generated Pdgfraflox/flox; Gli1-creERT2;ROSA26mTmg mice (PdgfraGli1, see Materials and Methods) and induced recombination by tamoxifen (TAM) on postnatal day (P) 2. Oral application of TAM worked reproducibly without loss of newborn mice, an important obstacle in such studies. Therefore, this regimen was adopted throughout the rest of this study.

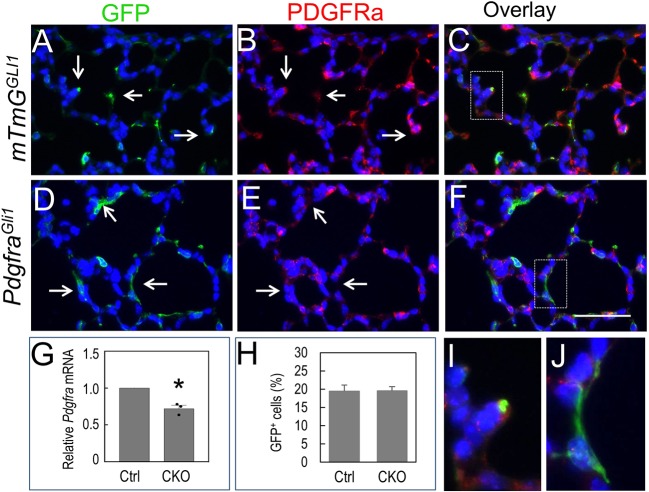

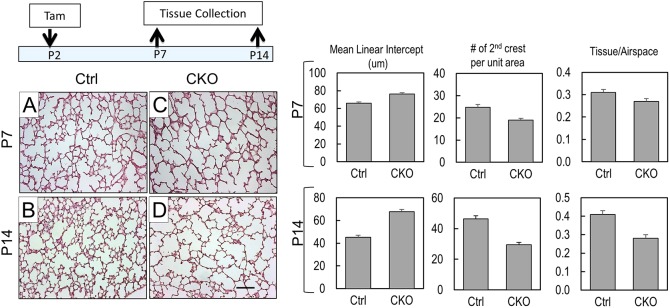

Inactivation of Pdgfra on P2 caused ∼30% reduction in total lung Pdgfra mRNA (Fig. 2). This is consistent with selective inactivation of Pdgfra by Gli1-creERT2 in SCMFs that, as a subpopulation, make up ∼20% of the total alveolar cell population (Fig. 2). Histology of multiple biological replicates of PdgfraGli1 lungs at P7 and P14 showed profoundly arrested alveolar phenotype (Fig. 1). Morphometric analysis revealed a 1.2- to 1.5-fold increase in mean linear intercept (MLI, P<0.05 for P7 and P14), coupled to 23% to 36% decrease in the number of secondary crests per unit area (P<0.05 for P7 and P14). Thus, postnatal Pdgfra inactivation selectively in SCMF is sufficient to produce an arrested phenotype nearly comparable with germline global deletion of Pdgfa reported by previous studies, indicating the importance of this cell type in alveologenesis (Boström et al., 1996; Lindahl et al., 1997).

Fig. 2.

PDGFRα is targeted in SCMF of P14 PdgfraGli1 lungs. (A-F) Double immunostaining of GFP and PDGFRα in P14 control (mTmGGli, A-C) and PdgfraGli1 conditional knockout (D-F) lungs. Arrows in A-C indicate PDGFRα-positive staining in GFPpos SCMF cells of control lungs. Arrows in D,E indicate PDGFRα-negative staining in GFPpos SCMF cells of PdgfraGli1 lungs. I and J show higher magnification of boxed areas in panels C and F, respectively. (G) Relative Pdgfra mRNA levels are reduced in PdgfraGli1 lungs (n=3). (H) Ratios of GFPpos cells to DAPIpos alveolar cells are similar between the control and mutant lungs. Multiple images from three Ctrl and three CKO lungs were analyzed (Ctrl: n=11; CKO: n=11). *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). Scale bar: 50 µm (A-F); 11.6 µm (I,J).

Fig. 1.

Pdgfra deficiency disrupts alveologenesis in PdgfraGli1 lungs. (A-D) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining of control (Ctrl; A,B) and PdgfraGli1 conditional knockout (CKO; C,D) lungs. Neonatal mice were treated with tamoxifen (TAM) on P2 and lungs were analyzed on P7 (A,C) and P14 (B,D). (Right) Multiple H&E images from three Ctrl and three CKO lungs were analyzed for mean linear intercept (MLI), number of secondary crests per unit area, and tissue/airspace ratio (P7: Ctrl, n=15; CKO, n=20. P14: Ctrl, n=13; CKO, n=13). Error bars represent s.e.m. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Proliferation and apoptosis in PdgfraGli1 lungs

PDGFA/PDGFRα is a known regulator of cell proliferation (Kimani et al., 2009). We examined whether the observed PdgfraGli1 phenotype is caused by alterations in cell proliferation or apoptosis. Quantification of Ki67pos cells using multiple samples of three independent biological replicates, showed a trend consistent with increased proliferation in the mutant lungs, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07, Fig. S1). Similarly, although there was a seemingly decreased number of TUNELpos cells, the difference was not significant (P=0.13, Fig. S1). Although these direct analyses indicate that conditional postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra does not result in significant cell death in PdgfraGli1 lungs, transcriptomic data showed cell survival as a major functional pathway associated with loss of Pdgfra (Fig. 5). It is possible that this discrepancy may simply reflect the resolution of RNA-seq technology compared with the other two more direct and specific analyses described in this section. To test this possibility, we defined the fate of targeted SCMF lacking PDGFRα activity, beginning on P2 by comparing, in parallel, the relative ratio of GFPpos cells with total alveolar cell counts in control and mutant lungs. This analysis revealed no change in the relative ratio of GFPpos cells in the two lungs, indicating absence of selective loss of mutant SCMF (Fig. 2). Thus, these observations indicate that the consequences of conditional inactivation of Pdgfra in the postnatal period contrast sharply with the previously reported significant loss of PDGFRαpos cells resulting from global deletion of Pdgfa (Boström et al., 1996), suggesting potential differences between the embryonic versus postnatal function of PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling.

Fig. 5.

Transcriptome of GFPpos SCMF. (A-E) GFPpos SCMF were isolated from P14 control (mTmGGli) and PdgfraGli1 lungs by FACS and used for RNA-seq analyses. (A) Principle component analyses of three control (Ctl) and two mutant samples. (B) Volcano plot shows the upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes (P<0.05, fold changes≥2) in the mutant samples compared with that of controls. (C) Top disrupted molecular and cellular functions identified by IPA analyses. (D) Top upstream regulators identified by IPA analyses. (E) Heatmap of elastogenic genes.

Cell differentiation in PdgfraGli1 lungs

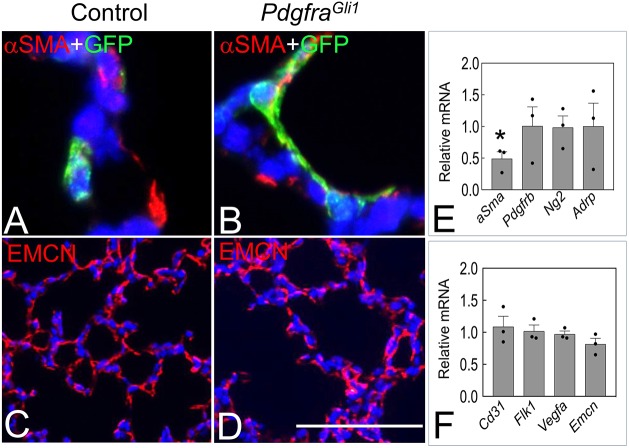

Information on postnatal cross-communication among various cell types that make up the secondary crest structures during alveologenesis is lacking. To determine whether blocked PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling in SCMF disrupts cross-communication that may be required for maintenance or differentiation of other cell types, we used quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to measure the expression of various cell type-specific markers. Sftpc, a marker of alveolar epithelial type 2 cells (AT2) was statistically unchanged (relative mRNA ratio: 0.90) (Fig. 3E). However, actual cell counts for AT2 cells, using multiple tissue preparations immunostained with anti-SFTPC antibody, revealed that the average number of SFTPCpos cells as a fraction of total alveolar cells was significantly reduced in the mutant lungs (15.8±1.1% in control versus 12.2±0.8% in mutants, P<0.05) (Fig. 3F). The decrease in SFTPCpos ratio was not associated with a decrease in proliferating SFTPCpos cells as determined by double immunostaining using Ki67 and SFTPC antibodies (Fig. 3G). Quantitative RT-PCR showed no significant change in mRNA for multiple AT1 cell markers, including Aqp5, Pdpn, Hopx and Rage (also known as Mok) (Fig. 3E). Consistent with the RNA results, ratio of HOPXpos to total alveolar cells was not significantly changed between the control and mutant lungs (Fig. 3H). Thus, postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra in SCMF reduces the relative abundance or differentiation of AT2 cells. In mesodermal lineages, the only detectable impact was on aSma (Acta2) (0.49, P<0.05), whereas markers for pericytes [i.e. Ng2 (Cspg4), Pdgfrb] and endothelial cells [CD31 (Pecam1), Flk1 (Kdr), Vegfa, Emcn] remained unchanged (Fig. 4). Consistent with these results, there was no discernible difference between control and mutant lungs in the endomucin (EMCN) expression pattern (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Epithelial cell differentiation in P14 PdgfraGli11 lungs. (A-D) Immunostaining of SFTPC (A,B) and HOPX (C,D) in P14 control (A,C) and PdgfraGli1 lungs (B,D). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Arrows indicate SFTPCpos cells in panels A and B, and HOPXpos cells in panels C and D. (E) qRT-PCR showing relative ratios of AT1 and AT2 markers in P14 PdgfraGli1 to control lungs (n=3). (F) Ratios of SFTPCpos to DAPIpos alveolar cells (Ctrl, n=19; CKO, n=27). (G) Ratios of Ki67pos/SFTPCpos to SFTPCpos cells (Ctrl, n=18; CKO, n=18). (H) Ratios of HOPXpos to DAPIpos alveolar cells (Ctrl, n=14; CKO, n=18). Data derived from multiple images from three control (Ctrl) and three PdgfraGli1 conditional knockout (CKO) P14 lungs. *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). Each bar represents mean± s.e.m. Scale bar: 32 µm.

Fig. 4.

Mesenchymal cell differentiation in PdgfraGli11 lungs. (A,B) Double immunostaining of GFP and αSMA in P14 control (A) and PdgfraGli1 lungs (B). (C,D) Immunostaining of EMCN in P14 control (C) and PdgfraGli1 lungs (D). (E,F) qRT-PCR of relative mRNA levels of fibroblast markers (E) and endothelial markers (F) in P14 PdgfraGli1 to control lungs (n=3). *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). Each bar represents mean±s.e.m. Scale bar: 22 µm (A,B); 100 µm (C,D).

Secondary crest formation requires Pdgfra activity

Secondary crests are identifiable as structures that physically arise from the primary septa and protrude into and divide the saccular space into smaller alveoli. In control lungs, we found immunoreactively positive cells for both GFP, marking SCMF, and PDGFRα localized to histologically identifiable secondary crest structures (Fig. 2). In contrast, many of the GFPpos cells in the PdgfraGli1 lungs were PDGFRαneg (Fig. 2). These mutant GFPpos cells were flat in shape compared with the controls that were round and localized to the tip of the normally formed secondary crests (Fig. 2). The flat-shaped cells likely represent progenitors or nascent SCMFs that remained within the primary septa and failed to give rise to secondary crests owing to lack of PDGFRα activity. They account for the differences in the total number of secondary crests between the control and the mutant lungs, as shown in Fig. 1. Thus, formation of the secondary crests during postnatal alveologenesis requires the activity of PDGFRα.

Transcriptome of isolated PdgfraGli1 SCMF

Cell-specific targets of the PDGFA/PDGFRa signaling network are not adequately known. In addition, these potential downstream targets, particularly in the neonatal lung, have remained largely uncharacterized. Availability and access to GFP-labeled SCMF, lacking Pdgfra, and appropriate controls presented the opportunity to define the gene expression profile of mutant SCMF and investigate the potential downstream targets of PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling by comparative transcriptomic analysis. GFPpos SCMF were isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from control (mTmGGli) and PdgfraGli1 lungs. The relative abundance of GFPpos cells recovered by FACS from either control or mutant lungs was ∼2% of the total sorted lung cells, again validating lack of significant cell death in PdgfraGli1 lungs as shown in the previous sections (Fig. S1). Isolated GFPpos cells were subjected to RNA-seq and the data were analyzed by PartekFlow, Heatmapper and IPA.

Principal component analysis using two variables revealed significant differences in gene expression between the control and PdgfraGli1 SCMF samples (Fig. 5A). There was a total of 1808 differentially expressed genes, of which 866 increased and 942 decreased in the mutant SCMF (Fig. 5B). Functional enrichment analysis indicated that the mutant SCMF were altered in multiple biological processes. These include cellular movement, cell survival and connective tissue development and functions (Fig. 5C). IPA analysis on potential upstream regulators showed alterations in multiple signaling pathways related to lung development. Interestingly, the top selected signaling pathways included many purported regulators of the elastogenic process, including TGFβ, FGF2, IGF1 and EGF (reviewed by Sproul and Argraves, 2013) (Fig. 5D). A heatmap representation of the elastogenic gene cluster, shown in Fig. 5E, illustrates a clear trend towards decreased expression of this class of genes in the PdgfraGli1 SCMFs.

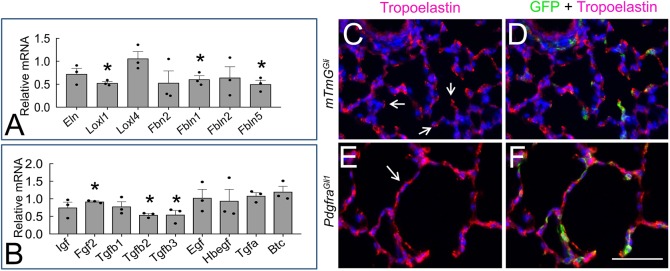

Pdgfra regulates genes in the postnatal elastogenesis pathway

Formation of secondary crests is dependent on expression and spatially correct distribution of ELN. Alterations in production and/or deposition of elastic fibers may be an important factor leading to arrested alveolar formation, such as that found in BPD (Bourbon et al., 2005). The RNA-seq analysis indicated alterations in a number of genes involved in production, assembly and deposition of ELN in PdgfraGli1 lungs. To validate the RNA-seq data, qRT-PCR was performed using RNA extracted from P14 control and PdgfraGli1 lungs. The relative ratio of total Eln mRNA was ∼28% lower in mutant lungs than in control lungs (P=0.09, Fig. 6A), even though no significant changes in Eln were detected by RNA-seq analysis. There was also reduced expression of lysyl oxidase-like 1 (Loxl1) (0.53, P<0.05, Fig. 6). In addition, there was quantifiable reduction in the relative abundance of Fbn2 (0.53, P=0.14), Fbln1 (0.61, P<0.05) and Fbln5 (0.50, P<0.05) in the mutant lungs. These data point to an encompassing dysregulation of multiple components of the elastogenic system in the PdgfraGli1 lungs, consistent with the SCMF RNA-seq data. Thus, although efficient Eln expression in the postnatal period is dependent on PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling, this pathway has a far-reaching impact on the complex elastogenic pathway.

Fig. 6.

ELN distribution is disrupted in P14 PdgfraGli1 lungs. (A,B) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic genes (A) and signaling molecules that regulate elastogenesis (B) in P14 control and mutant lungs (n=3). Each bar represents average ratio (mutant versus control)±s.e.m. *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). (C-F) Double immunostaining of GFP and tropoelastin in P14 control (C,D) and PdgfraGli1 lungs (E,F). Arrows in C indicate ELN deposition at the tips of secondary crests. Arrow in E indicates strong ELN staining in primary septa. Scale bar: 50 µm.

To determine whether dysregulation of elastogenic genes resulted in alterations in processing or deposition of ELN fibers, we performed immunohistochemistry with anti-tropoelastin antibodies on P14 lungs. In control lungs, tropoelastin was organized with a low-to-high gradient from primary septa to the tip of the secondary crest, where it forms concentrated moieties (Fig. 6, arrows). In contrast to this pattern, ELN fibers in the PdgfraGli1 lungs were flat and spread along the walls of enlarged alveoli. This abnormal pattern of ELN deposition presumably is related to, or the cause of, failure in septation and the consequent blocked alveolar phenotype in the mutant lungs (Fig. 1).

Lack of Pdgfra in SCMF alters expression of ligands in secondary signaling pathways

To further examine the underlying causes of abnormal ELN distribution in PdgfraGli1 lungs, we examined the expression of signaling molecules uncovered by RNA-seq analysis in Fig. 5D. A number of signaling networks are reported to be associated with elastogenesis (reviewed by Sproul and Argraves, 2013). Among these are TGFβ, IGF1, FGF2 and EGF. In PdgfrαGli1 lungs, transcripts for Tgfb1 were not significantly changed (0.78, P=0.18) but there was a significant reduction in relative abundance of both Tgfb2 (0.54, P<0.05) and Tgfb3 (0.55, P<0.05). We also found a slight reduction in Fgf2 (0.92, P<0.05), although no significant change was detectable in Igf1 and EGF family members (Fig. 6).

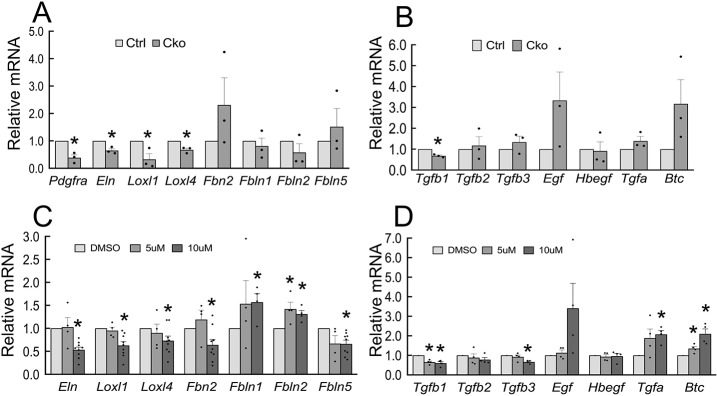

To determine the direct impact of PDGFRα deficiency on SCMF, we prepared RNA from control and mutant FACS-isolated SCMFs (GFPpos). qRT-PCR analysis showed significant reduction in Pdgfra (0.39, P<0.05), Eln (0.65, P<0.05), Loxl1 (0.33, P<0.05), Loxl4 (0.67, P<0.05). Fbn2 (2.31, P=0.32), Fbln1 (0.81, P=0.58), Fbln2 (0.58, P=0.32) and Fbln5 (1.52, P=0.52) also changed but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7A). There was also a quantifiable reduction in Tgfb1 (0.68, P<0.05), whereas transcripts for several EGF family members [Egf (3.34, P=0.16), Tgfa (1.39, P=0.21) and Btc (3.17, P=0.13)] were increased in mutant SCMFs (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Pdgfra deficiency disrupts elastogenic gene expression. (A,B) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic genes and related signaling molecules in sorted GFP+ cells of P14 control and PdgfraGli1 lungs (n=3). (C,D) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic genes and related signaling molecules in primary lung fibroblasts cultured in the presence of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide, carrier, as control), and either 5 μm or 10 μm of imatinib (n=4-9). *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). Each bar represents mean±s.e.m.

The results of these in vivo findings suggest that PDGFA signaling regulates elastogenic gene expression. To test the validity of these findings, we isolated primary fibroblasts from P5 lungs and cultured them in the presence or absence of two doses of imatinib, a well-established and widely used pharmacological inhibitor of the PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling pathway (McGowan and McCoy, 2011). As shown in Fig. 7C, 10 µM of imatinib reduced Eln (0.53, P<0.05), Loxl1 (0.63, P<0.05), Loxl4 (0.73, P<0.05), Fbn2 (0.64, P<0.05) and Fbln5 (0.66, P<0.05). Importantly, imatinib decreased all three TGFβ transcripts [Tgfb1 (0.60, P<0.05), Tgfb2 (0.78, P=0.11), Tgfb3 (0.66, P<0.05)], and increased mRNA for several EGF family members, including Egf (3.41, P=0.11), Tgfa (2.07, P<0.05), and Btc (2.10, P<0.05) (Fig. 7D).

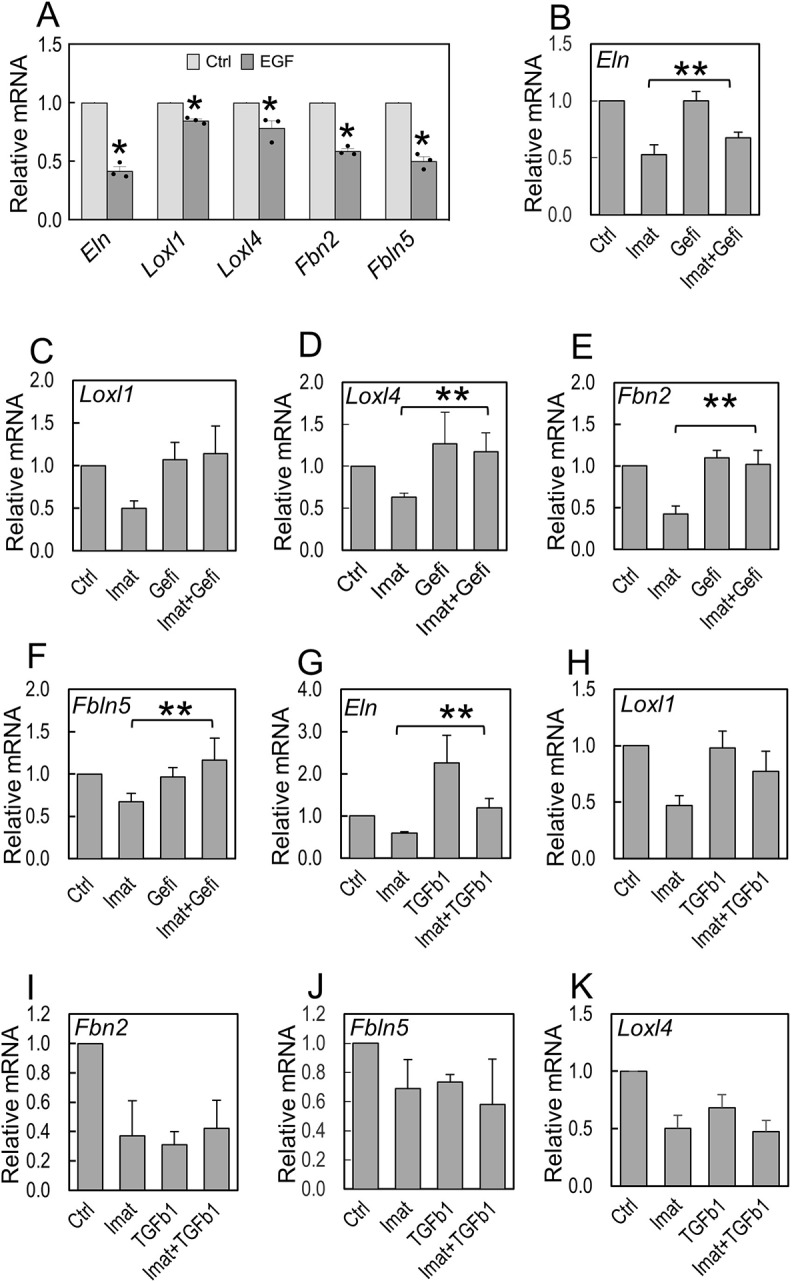

Blocking EGF rescues ELN abnormalities in lung fibroblasts

The observation that members of the EGF family of genes were increased in isolated PdgfraGli1 SCMF in association with ELN abnormalities prompted us to investigate whether the impact of Pdgfra inactivation is mediated via EGF signaling. To this end, we first examined whether recombinant EGF inhibited expression of the elastogenic genes which we found to be dysregulated in PdgfraGli1 lungs. In cultured P5 primary lung fibroblasts, 20 ng/ml of human recombinant EGF repressed the steady state level of Eln (0.42, P<0.05), Loxl4 (0.78, P<0.05), Fbn2 (0.59, P<0.05) and Fbln5 (0.5, P<0.05), but had minor impact on Loxl1 (0.85, P<0.05) (Fig. 8A). We next examined whether treatment of P5 cells with gefitinib, a potent pharmacological inhibitor of EGFR, could rescue the impact of imatinib-inhibition on the same elastogenic genes. In each case, 1 µM of gefitinib almost completely reversed the inhibitory effect of imatinib and almost restored normal levels of Loxl1, Loxl4, Fbn2 and Fbln5 (Fig. 8C-F). However, gefitinib failed to rescue imatinib-induced inhibition of Eln (Fig. 8B). Thus, with the exception of Eln, increased EGF mediates repression of this cluster of elastogenic genes induced by inhibition of PDGFA signaling. We next addressed the role of TGFβ signaling by examining whether recombinant TGFβ1 could rescue the imatinib-inhibited elastogenic gene cluster. As shown in Fig. 8G, TGFβ1 increased Eln expression, and more importantly, overcame the inhibitory effect of imatinib. TGFβ1 also partially rescued Loxl1 but failed to rescue other elastogenic genes (Fig. 8H-K). Therefore, lack of signaling via PDGFRα alters EGF and TGFβ, which differentially regulate elastogenic genes in lung fibroblasts. In sum, EGF negatively regulates Loxl1, Loxl4, Fbn2 and Fbln5, whereas TGFβ1 positively regulates Eln and Loxl1. These findings illustrate the complex role of PDGFA/PDGFRα in a multi-signaling interactive regulatory network that ultimately controls the expression of a battery of elastogenic genes that are necessary for normal alveolar formation in the postnatal period.

Fig. 8.

EGF and TGFβ differentially regulate elastogenic gene expression. (A) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic gene expression in primary lung fibroblasts cultured in presence of carrier (Ctrl) or 20 ng/ml of human EGF (n=3). *P<0.05 (two tailed Student's t-test). (B-F) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic gene expression in primary lung fibroblasts cultured in presence of carrier (Ctrl), 10 µM imatinib (Imat), 1 µM of gefitinib (Gefi), or imatinib plus gefitinib (Imat+Gefi) (n=5). (G-K) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic gene expression in primary lung fibroblasts cultured in the presence of carrier (Ctrl), 10 µM imatinib (Imat), 2 ng/ml TGFβ1, or imatinib plus TGFβ1 (n=5). **P<0.05 when compared with Imat only condition (2nd bar in each group; two tailed Student's t-test)). Each bar represents mean±s.e.m.

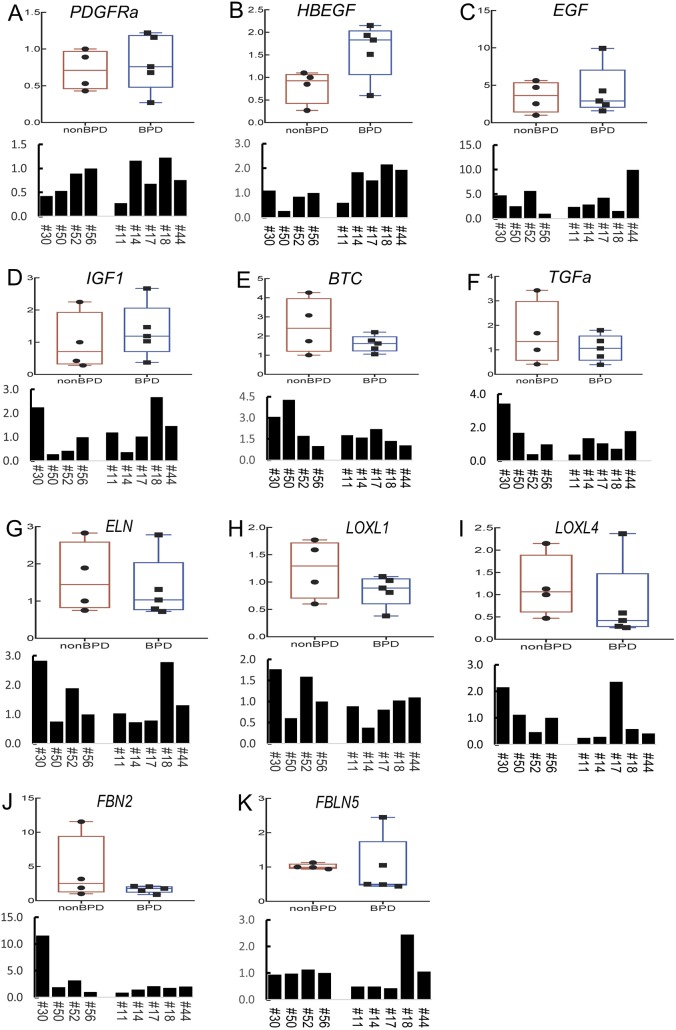

Dysregulated elastogenic gene cluster in human BPD

To examine the relevance of our mouse findings to human lung alveolar diseases, we analyzed expression of the elastogenic genes described above in de-identified human BPD samples. Histological assessment of BPD is consistent with a phenotype of arrested alveolar development (Husain et al., 1998). This feature has been phenocopied in neonatal mice by various injuries, including exposure to hyperoxia (Dasgupta et al., 2009). We used lung samples from a total of nine individuals who died in the neonatal period. Four of the samples, including #30, #50, #52 and #56, were from neonates who died with ‘no or very mild Respiratory Distress Syndrome or RDS’ (death due to non-pulmonary causes). We chose these samples as ‘control’ because, although ‘normal’ early embryonic human samples are available from abortions, bioethical reasons make postnatal samples extremely rare. qRT-PCR of the mouse elastogenic genes in human BPD samples showed the expected large variability among different human samples. Despite this variability, there was a general trend towards decreased expression of LOXL1, LOXL4 and FBN2 as shown by the boxplots in Fig. 9H-J. However, expression of HBEGF, a member of the EGF family, was significantly increased in human BPD samples (P<0.05, Fig. 9B). Of interest, the direction of change in sample #14, an early BPD sample, was always consistent with the mouse data (Fig. 9). On the whole, the findings in what is admittedly a limited number of human BPD samples appears to generally recapitulate the findings in the PdgfraGli1 mouse model.

Fig. 9.

Elastogenic gene expression in human BPD lungs. (A-K) qRT-PCR analyses of elastogenic genes and related signaling molecules in human BPD lung samples. Collection and processing of the lung samples from the deceased were conducted at the University of Rochester and were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board. Samples #11, #14, #17, #18 and #44 were from BPD patients. Samples #30, #50, #52 and #56 were from patients not diagnosed with BPD. The column chart shows relative mRNA levels of the tested gene (indicated in the chart) compared with that of #56 (arbitrarily set as 1). The boxplots show data distribution of non-BPD (left) and BPD (right) samples. Top bar indicates maximum value and bottom bar minimum value. Box represents first (bottom) to third (top) quartile. Dots represent individual samples and median is marked by a horizontal line.

DISCUSSION

Alveolar formation in the mouse occurs exclusively in the postnatal period. Few studies have addressed the specific postnatal mechanisms that underlie this vitally important process. The first clues that the PDGFA/PDGFRα axis may have a role in alveologenesis came from global (null) deletions of Pdgfa or Pdgfra (Boström et al., 1996; Lindahl et al., 1997). However, the null genetic approach in general precludes the possibility of ascertaining whether a phenotype is the consequence of interrupting postnatal processes or embryonic ones that precede it. Pdgfra is expressed throughout the lung mesoderm from the onset of its morphogenesis. In addition, the previous null deletion studies were postnatally lethal and resulted in ubiquitous lack of the PDGFA/PDGFRα pathway and depletion of PDGFRαpos cells due to widespread cell death (Lindahl et al., 1997). Thus, the role, if any, of the PDGFA/PDGFRα pathway in alveolar formation had remained unknown. Recently, postnatal depletion of PDGFRαpos cells was shown to cause alveolar hypoplasia (Li et al., 2018). Although this was a clear demonstration that the PDGFRαpos cell population is specifically required for alveolar formation, the study could not address the specific function of PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling, also owing to cell death.

In the present study, we show that postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra targeted to SCMF, a sub-lineage of lung PDGFRαpos cells, causes an arrested alveolar phenotype, comparable with that caused by null mutations of Pdgfa or Pdgfra. Importantly however, unlike the previous studies, the arrested alveologenesis in PdgfraGli1 lungs occurs without widespread loss of GFPpos SCMFs (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, early postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra in SCMF did not appear to block their differentiation as shown by positive staining for αSMA in GFPpos cells (Fig. 4B). Whether αSMA immuno-intensity represents aSma RNA changes observed by qRT-PCR remains unknown owing to the inherent non-quantifiable nature of immunostaining (Fig. 4E). Nevertheless, the findings of the present study have enabled us to draw two important conclusions regarding the function of PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling in lung development that were previously unrecognized. First, abrogation of PDGFA signaling via conditional inactivation of Pdgfra in the postnatal period does not alter the relative abundance of GFPpos SCMFs. This contrasts with significant loss of SCMFs in Pdgfa−/− lungs (Boström et al., 1996). Second, owing to the absence of cell death, the results provide the first direct evidence that postnatal signaling via PDGFRα is required for alveologenesis.

Alveologenesis requires significant cell migration as the secondary crests emerge from the primary septa to form alveoli. PDGFA/PDGFRα signaling regulates migration of lung mesenchymal cells (McGowan and McCoy, 2018). The conditional targeted genetic approach used in this study found alterations in gene expression that were consistent with defects in SCMF migration in PdgfraGli1 lungs. A large number of SCMFs in PdgfraGli1 lungs were flat in shape and spread out on primary septa, indicating the strong possibility of failed secondary crest eruption. IPA analysis of RNA-seq data revealed migration as the top affected cellular function in mutant SCMF (Fig. 5). Cell migration is regulated by multiple genes, an important class of which encode members of the extracellular matrix proteins (ECM). We found robust and widespread changes in various collagen mRNAs. Of the 112 ECM genes examined, 106 were changed greater than 2-fold, with a P-value <0.05. With the exception of Col6a4, which in many organs is associated with fibrosis, we found decreased ECM molecules in PdgfraGli1 lungs. Collagen type IV isoforms including Col4a3, Col4a4 and Col4a6 were significantly decreased. Type IV collagens localize to the basement membrane of epithelial and interstitial endothelial cells where SCMFs are anchored. In previous reports, postnatal inactivation of Type IV collagen caused defective ELN production and deposition, and defects in alveologenesis and epithelial cell differentiation (Loscertales et al., 2016). In our study, we also found significant changes in multiple integrins (e.g. Itga4: 0.54, FDR 6.99E-02; Itga7: 0.39, FDR 4.80E-09; Itga8: 0.35, FDR 3.27E-14; Itgb8: 0.46, FDR 5.76E-04), which mediate cell-ECM interactions and are crucial for cell migration. Alterations in lung collagen levels and disorganization of ECM fibers have been reported in preterm infants with BPD (Thibeault et al., 2003).

A recognized feature of alveolar defects that is associated with lack of Pdgfa or Pdgfra in various reported models is reduced or absent ELN synthesis and/or abnormal deposition (Lindahl et al., 1997; McGowan and McCoy, 2014). The mechanisms have remained unknown. There is now reliable evidence that ELN synthesis and deposition occur in a biphasic manner (Branchfield et al., 2016). Global Pdgfa deletion, although not affecting tropoelastin before birth, is reported to cause complete postnatal absence of tropoelastin that is associated with widespread loss of PDGFRαpos cells (Boström et al., 1996; Lindahl et al., 1997). Thus, whether or not PDGFA is required for Eln expression during alveologenesis had remained unknown. In our study, postnatal inactivation of Pdgfra did not cause widespread cell death, but reduced Eln expression in isolated SCMF. Therefore, PDGFA signaling appears to be at least partly required for efficient expression of Eln in SCMF (Fig. 7). In addition, deposition of ELN fibers was clearly abnormal (Fig. 6). Elastogenesis is a complex and highly regulated process (Sproul and Argraves, 2013). Disrupted elastogenesis leads to abnormal alveologenesis (Wendel et al., 2000; McGowan and McCoy, 2014; Li et al., 2017). In the lung, the mechanisms that functionally link PDGFRα and elastogenic genes had remained unknown. Of the five lysyl oxidases required for integrity and elasticity of mature ELN, Loxl1 was significantly reduced in PdgfraGli1 lungs (Fig. 6). In addition, we found dysregulation of Fbn2, Fbln1 and Fbln5 mRNA, which encode three ECM proteins implicated in ELN assembly and deposition (Fig. 6). In the mouse hyperoxia model, which also causes alveolar arrest, tropoelastin was dysregulated, whereas Loxl1, Fbn2 and Fbln5 remained unchanged (Bland et al., 2008). Thus, although ELN abnormalities may be a hallmark of alveolar injury, the underlying mechanisms and whether it involves dysregulated elastogenic genes may depend on the mode of experimentally induced injury. In support of this hypothesis, we found that even though Eln, Loxl1 and Loxl4 were consistently reduced under all PDGF-deficient conditions, there was differential impact on Fbn2, Fbln1, Fbln2 and Fbln5, depending on the experimental conditions (Figs 6, 7 and 8).

PDGFRA controls a second tier of signaling networks

The transcriptome of control and mutant SCMF revealed alterations in key signaling networks implicated in the elastogenic process. We show that two such networks, EGF and TGFβ, regulate the expression of elastogenic genes. The EGF family members Egf, Tgfa and Btc were increased in both mutant SCMF (Fig. 7B) and P5 fibroblasts treated with imatinib (Fig. 7D). A number of EGF ligands, including EGF, HBEGF, BTC and TGFα, interact with the tyrosine kinase receptor EGFR to affect proliferation, differentiation and survival (Siddiqui et al., 2012). EGF/EGFR signaling is a crucial regulator of lung morphogenesis (Miettinen et al., 1997; Plopper et al., 1992). Disrupted expression of EGFR and its ligands EGF, TGFα and BTC have been reported in BPD (Strandjord et al., 1995; Cuna et al., 2015). In mice, our findings are consistent with the report that overexpression of Btc disrupts alveologenesis (Schneider et al., 2005). In contrast to mice, we found decreased BTC in human BPD samples (Fig. 9E). Decreased BTC has been reported in other human BPD studies (Cuna et al., 2015) and likely reflects a failed compensatory response, particularly in late BPD samples. Intriguingly, and again in contrast to the mouse lung, transcripts for HBEGF, an EGF family member in human BPD lungs, were increased, whereas EGF remained unchanged. In support of a role for EGF, we show that recombinant EGF treatment of P5 lung fibroblasts inhibits Eln, Loxl1, Loxl4, Fbn2 and Fbln5. Furthermore, we show that gefitinib, a potent EGFR inhibitor, can rescue and almost completely reverse the imatinib-induced inhibition of the same elastogenic genes, except Eln. In conclusion, regardless of the specific ligand, overactivation of the EGF pathway appears to be a common molecular mechanism in both human BPD and PdgfraGli1 mouse lungs.

Several studies have shown that EGF signaling indeed negatively regulates elastogenesis (Ichiro et al., 1990; Le Cras et al., 2004; DiCamillo et al., 2006; Bertram and Hass, 2009). Further analyses revealed that activation of ERK mediates EGF inhibition of elastogenesis. Inhibition of ERK blocked EGF effects on elastogenesis (Liu et al., 2003; DiCamillo et al., 2002; DiCamillo et al., 2006), whereas activation of ERK inhibited elastogenesis (Lannoy et al., 2014). Consistent with these reports, we found that levels of p-ERK were indeed increased in the PdgfraGli1 lungs (Fig. S2), in which elastogenic gene expression was decreased. Finally, as a first attempt, we examined whether blocking EGF signaling in vivo would reverse the alveolar hypoplasia phenotype in PdgfraGLi1 lungs. PdgfraGLi1 pups were treated by oral gavage with gefitinib on P4. As shown in Fig. S3, gefitinib failed to rescue the hypoplastic phenotype of PdgfraGLi1 lungs. This is likely because of the pleiotropic role of EGF in many important processes including cell proliferation and migration, which are also crucial for alveologenesis.

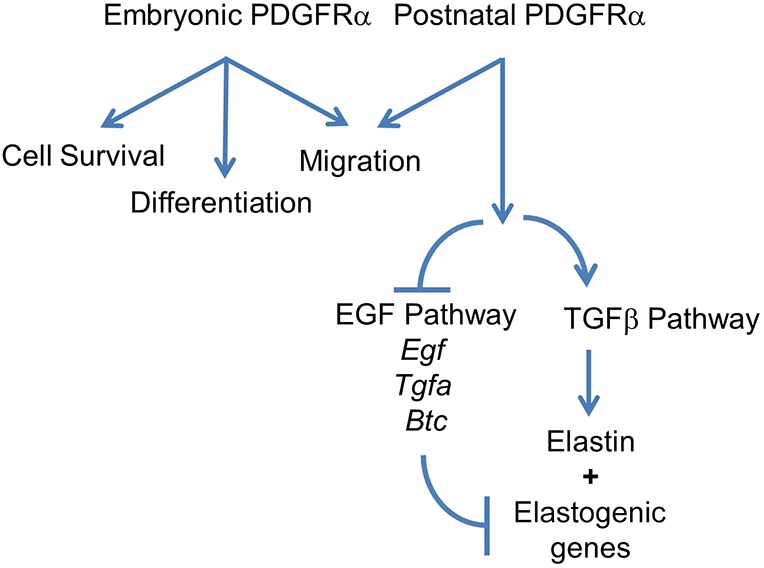

The other second tier pathway affected by lack of PDGFRα is TGFβ. In the lung, the role of TGFβ appears to be dose- and time-dependent. Application of a supraphysiological dose of TGFβ, or TGFβ induced via hyperoxia, arrests alveolar formation (Vicencio et al., 2004). In contrast, one study has shown that antibody-blockade of TGFβ disrupts alveologenesis in lung explants (Pieretti et al., 2014). We found TGFβ signaling in SCMFs to be important in regulating elastic fiber formation. Interestingly, our results show that TGFβ and EGF each regulate a distinct group of elastogenic genes, with partial overlap. TGFβ controls Eln and Loxl1, whereas EGF regulates Loxl1, Loxl4, Fbn2, Fbln1 and Fbln5. This illustrates the requirement for integration of multiple convergent signaling pathways in the genetic architecture of the elastogenesis regulatory network, the overall function of which is essential for normal alveolar formation in the postnatal period (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Simplified model illustrating PDGFRα functions in elastogenesis. Previous studies have shown that PDGFA is essential for migration and survival of PDGFRαpos cells during embryonic development (Bostrom et al., 1996; Lindahl et al., 1997). The current study revealed the cell type-specific function of PDGFRα during alveologenesis. Postnatal PDGFRα is crucial in the regulation of elastogenesis, which involves EGF and TGFβ signaling. Arrows indicate positive regulation. Lines indicate inhibition.

Finally, we were intrigued by the findings that alterations in SCMF affect the AT2 cell abundance, represented by the reduced ratio of SFTPCpos cells in the PdgfraGli lungs (Fig. 3). In 3D organoid cultures, unfractionated PDGFRapos cells are known to exhibit unique properties in supporting and promoting adult AT2 cell proliferation and differentiation (Barkauskas et al., 2013). In the adult lung, PDGFRαpos cells were reported to be spatially located in close juxtaposition to AT2 cells, suggesting they are components of the alveolar epithelial niche environment (Nabhan et al., 2018; Zepp et al., 2017). These observations support an active functional cross-talk between PDGFRαpos and AT2 cells in adult lung. PDGFRα is expressed by lipofibroblasts and myofibroblasts in both neonatal and adult lungs (Barkauskas et al., 2013; McGowan and McCoy, 2014; Endale et al., 2017). However, the Gli1-creERT2 driver line used in the present study to inactivate Pdgfra is not known to target lipofibroblasts (Li et al.; 2015). Therefore, it is highly likely that the reduced number of AT2 cells in PdgfraGli1 lungs is causally linked to lack of Pdgfra in SCMF. Thus, the mechanism must involve alterations in signaling molecules that are expressed by mutant SCMF that otherwise mediate the process of cross-talk with the epithelial cells. Recent studies have identified several signaling candidates that regulate AT2 cell abundance. For example, canonical WNT signaling mediates maintenance of the SFTPCpos/Axin2pos alveolar epithelial progenitor pool (Frank et al., 2016). RNA-seq data generated in our study showed a mixed response of WNT ligands to Pdgfra deficiency (Wnt4: 0.61, FDA 9.72 E-2; Wnt5a: 2.04, FDA 5.14 E-47; Wnt6: 3.62, FDA 3.57 E-2). The net effect of the latter changes on WNT activity in AT2 cells is difficult to predict and remains to be determined more specifically in future studies. Other signaling pathways such as FGF10, HGF and Notch have also been shown to regulate epithelial cell proliferation during development and during injury repair (Panos et al., 1996; McQualter et al., 2010; Vaughan et al., 2015). Interestingly, levels of Fgf10 (0.33, FDA 3.74 E-10), Hgf (0.30, FDA 4.56 E-01) and the NOTCH ligand Jag1 (0.47, FDA 5.93 E-10) were all decreased in the PDGFRα-deficient SCMF cells. More detailed and directed studies that are needed to identify the ligand/receptor complements and the mechanisms that mediate the SCMF-AT2 cross-talk are currently underway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse breeding and genotyping

All animals were maintained and housed in pathogen-free conditions according to a protocol approved by The University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Gli1-creERT2;Rosa26mTmG mice (mTmGGli) were generated by breeding Gli1-creERT2 (Ahn and Joyner, 2004) and Rosa26mTmG mice [Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato-EGFP)Luo/J, The Jackson Laboratory]. mTmGGli mice were then bred with the Pdgfraflox/flox mice (The Jackson Laboratory, 006492) to generate Gli1-creERT2;Rosa26mTmG;Pdgfraflox/flox (PdgfraGli1) mice on C57BL genetic background. Genotyping of the transgenic mice was performed using PCR with genomic DNA isolated from mouse tails. Forward (F) and reverse primers (R) for transgenic mouse genotyping were: Gli1-creERT2 F 5′-TAAAGATATCTCACGTACTGACGGTG-3′ and R 5′-TCTCTGACCAGAGTCATCCTTAGC-3′; Pdgfraflox/flox F 5′-CCCTTGTGGTCATGCCAAAC-3′, wild-type R 5′-GCTTTTGCCTCCATTACACTGG-3′ and flox-R 5′-ACGAAGTTATTAGGTCCCTCGAC-3′. Both male and female mice were used in each of the experiments.

Human neonatal lung samples

Human lung tissue samples were obtained postmortem by expedited autopsy of preterm infants having the diagnoses of mild RDS, evolving and established BPD, and term infants as controls (no lung disease). Consent for autopsy, including a release of tissue for research, was obtained before collection of tissues. The study meets the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (privacy) compliance. Collection and processing of the lung samples as from the deceased were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board. Selected clinical details have been previously published (Bhattacharya, et al., 2012).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed as previously described (Li et al., 2009). Paraffin sections of the lung tissue at 5 µm were deparaffinized and rehydrated using an ethanol gradient series to water. After antigen retrieval with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) tissue sections were blocked with normal serum and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. A combination of fluorescein anti-mouse and Cy3 anti-rabbit or anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, ING) was applied to detect specific primary antibodies. After washing with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, the sections were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to counterstain nuclei. Primary antibodies used in this study were authenticated by the commercial source or validated in our own preliminary studies. The antibodies are listed in Table S2.

Tamoxifen administration

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, 8 mg/ml in peanut oil) was administered by oral gavage to neonates at P2 (400 µg each pup) with a plastic feeding needle (Instech Laboratories). Lungs of PdgfraGli1 and littermate controls were collected at P7 to P14 for morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular biological analyses.

Neonatal lung fibroblast isolation and treatment

Wild-type neonatal lungs at P5 were dissected in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Gibco, 24020-117). Lungs were inflated with dispase, tied at the trachea and then digested by continuous shaking in dispase at 37°C for 15 min. At the end of the incubation, lung lobes were isolated by dissection, cut into small pieces, transferred into Miltenyi tubes in 5 ml HBSS and dissociated using a gentle MACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). The dissociated cells were diluted in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), filtered through a 40 µm cell strainer to remove tissue debris and then pelleted by centrifugation at 1200 rpm (248 g) for 5 min. After washing with PBS, cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS, plated in cell culture plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. After removing floating cells, the attached fibroblasts were washed with PBS and cultured in fresh medium. When the fibroblasts grew to near confluency, they were trypsinized and seeded on 12-well plates at 100,000 cells/well. At 80% confluency, the cells were washed with PBS and then treated with growth factor or inhibitors as indicated in each experiment in DMEM containing 1% FBS. After 48 h, the cells were collected for RNA analyses. The cells were authenticated for absence of contaminations.

RNA-seq analyses

mTmGGli and PdgfraGli1 lungs, which received TAM at P2, were dissected at P14. GFPpos cells were sorted by flow cytometry directly into RLT define buffer at the University of Southern California Stem Cell Flow Cytometry Facility using the FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) cell sorter. RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Micro kit and then submitted to the Millard and Muriel Jacobs Genetics and Genomics Laboratory at Caltech for sequencing, which was run at 50 bp, single end, and 30 million reading depth. The unaligned raw reads from aforementioned sequencing were processed on the PartekFlow platform. In brief, read alignment, and gene annotation and quantification, were based on mouse genome (mm10) and transcriptome (GENECODE genes-release 7). Tophat2 and Upper Quartile algorithms were used for mapping and normalization. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using PartekFlow's Gene Specific Analysis module (GSA). The exported differential gene expression dataset was further processed for visualization, gene ontology and pathway analysis using software including XLSTAT (an add-on of Microsoft Excel), Panther Classification System, Heatmapper (Babicki et al., 2016) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Expression of selected genes was quantified by qRT-PCR using a LightCycler with LightCycler Fast Start DNA Master SYBR Green I Kit (Roche Applied Sciences) as previously described (Li et al., 2005). Relative ratios of a target gene transcript in PdgfraGli1 and littermate control lungs were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Primers for qRT-PCR were designed using the program of Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center from Roche Applied Sciences. The primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

At least three biological replicates for each experimental group and at least two or more biological replicates for the control lungs were used for each morphometric analysis, cell counting and qRT-PCR analyses. Multiple images as indicated in each figure legend were used to count MLI, the number of secondary crests and tissue/airspace ratios (10× magnification), GFPpos cell ratio (40× magnification), SFTPCpos cell ratio (40× magnification), Ki67pos/SFTPCpos cell ratio (40× magnification), HOPXpos cell ratio (20× magnification), Ki67pos cell ratio (20× magnification) and TUNELpos cell ratio (10× magnification). MLI and the number of secondary crests were measured manually. Tissue/airspace ratios were measured using ImageJ. Quantitative data are mean±s.e.m. P values were calculated using the two tailed Student's t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Hongyan Chen, Claudia Wang and Kim Ngo for their excellent technical support. We thank Dr Alexandra Joyner (Sloan Kettering Institute, NY, USA) for providing and Dr Arturo Alvarez-Buylla (University of California San Francisco, CA, USA) for making available the Gli1-creERT2 mice.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.L., S.B., P.M.; Methodology: C.L., M.K.L., F.G., P.M.; Investigation: C.L., M.K.L., F.G., S.W., H.D., J.D., C.-Y.Y., N.B., N.P., G.P., S.M.S., P.M.; Writing - original draft: C.L., P.M.; Writing - review & editing: C.L., G.P., Z.B., S.B., P.M.; Supervision: C.L., P.M.; Project administration: C.L., P.M.; Funding acquisition: C.L., Z.B., P.M.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [HL122764, HL143059, HL144932 to C.L. and P.M.; HL135747 to Z.B. and P.M.] and the Hastings Foundation. Z.B. is Ralph Edgington Chair in Medicine and P.M. is Hastings Professor of Pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data have been deposited with GEO under the accession number GSE126457.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.176354.supplemental

References

- Ahn S. and Joyner A. L. (2004). Dynamic changes in the response of cells to positive hedgehog signaling during mouse limb patterning. Cell 118, 505-516. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babicki S., Arndt D., Marcu A., Liang Y., Grant J. R., Maciejewski A. and Wishart D. S. (2016). Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W147-W153. 10.1093/nar/gkw419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkauskas C. E., Cronce M. J., Rackley C. R., Bowie E. J., Keene D. R., Stripp B. R., Randell S. H., Noble P. W. and Hogan B. L. M. (2013). Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3025-3036. 10.1172/JCI68782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram C. and Hass R. (2009). Cellular senescence of human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC) is associated with an altered MMP-7/HB-EGF signaling and increased formation of elastin-like structures. Mech. Ageing Dev. 130, 657-669. 10.1016/j.mad.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Go D., Krenitsky D. L., Huyck H. L., Solleti S. K., Lunger V. A., Metlay L., Srisuma S., Wert S. E., Mariani T. J. et al. (2012). Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals connective tissue mast cell accumulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 186, 349-358. 10.1164/rccm.201203-0406OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland R. D., Ertsey R., Mokres L. M., Xu L., Jacobson B. E., Jiang S., Alvira C. M., Rabinovitch M., Shinwell E. S. and Dixit A. (2008). Mechanical ventilation uncouples synthesis and assembly of elastin and increases apoptosis in lungs of newborn mice. Prelude to defective alveolar septation during lung development? Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 294, L3-L14. 10.1152/ajplung.00362.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boström H., Willetts K., Pekny M., Levéen P., Lindahl P., Hedstrand H., Pekna M., Hellström M., Gebre-Medhin S., Schalling M. et al. (1996). PDGF-A signaling is a critical event in lung alveolar myofibroblast development and alveogenesis. Cell 85, 863-873. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81270-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boström H., Gritli-Linde A. and Betsholtz C. (2002). PDGF-A/PDGF alpha-receptor signaling is required for lung growth and the formation of alveoli but not for early lung branching morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 223, 155-162. 10.1002/dvdy.1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucherat O., Morissette M. C., Provencher S., Bonnet S. and Maltais F. (2016). Bridging lung development with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. relevance of developmental pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 193, 362-375. 10.1164/rccm.201508-1518PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbon J., Boucherat O., Chailley-Heu B. and Delacourt C. (2005). Control mechanisms of lung alveolar development and their disorders in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Res. 57, 38R-46R. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159630.35883.BE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchfield K., Li R., Lungova V., Verheyden J. M., McCulley D. and Sun X. (2016). A three-dimensional study of alveologenesis in mouse lung. Dev. Biol. 409, 429-441. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuna A., Halloran B., Faye-Petersen O., Kelly D., Crossman D. K., Cui X., Pandit K., Kaminski N., Bhattacharya S., Ahmad A. et al. (2015). Alterations in gene expression and DNA methylation during murine and human lung alveolar septation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 53, 60-73. 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0160OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta C., Sakurai R., Wang Y., Guo P., Ambalavanan N., Torday J. S. and Rehan V. K. (2009). Hyperoxia-induced neonatal rat lung injury involves activation of TGF-β and Wnt signaling and is protected by rosiglitazone. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 296, L1031-L1041. 10.1152/ajplung.90392.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCamillo S. J., Carreras I., Panchenko M. V., Stone P. J., Nugent M. A., Foster J. A. and Panchenko M. P. (2002). Elastase-released epidermal growth factor recruits epidermal growth factor receptor and extracellular signal-regulated kinases to down-regulate tropoelastin mRNA in lung fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18938-18946. 10.1074/jbc.M200243200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCamillo S. J., Yang S., Panchenko M. V., Toselli P. A., Naggar E. F., Rich C. B., Stone P. J., Nugent M. A. and Panchenko M. P. (2006). Neutrophil elastase-initiated EGFR/MEK/ERK signaling counteracts stabilizing effect of autocrine TGF-beta on tropoelastin mRNA in lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 291, L232-L243. 10.1152/ajplung.00530.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endale M., Ahlfeld S., Bao E., Chen X., Green J., Bess Z., Weirauch M., Xu Y. and Perl A. K. (2017). Dataset on transcriptional profiles and the developmental characteristics of PDGFRα expressing lung fibroblasts. Data Brief 13, 415-431. 10.1016/j.dib.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D. B., Peng T., Zepp J. A., Snitow M., Vincent T. L., Penkala I. J., Cui Z., Herriges M. J., Morley M. P., Zhou S. et al. (2016). Emergence of a wave of Wnt signaling that regulates lung alveologenesis by controlling epithelial self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Rep. 17, 2312-2325. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain A. N., Siddiqui N. H. and Stocker J. T. (1998). Pathology of arrested acinar development in postsurfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum. Pathol. 29, 710-717. 10.1016/S0046-8177(98)90280-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiro T., Tajima S. and Nishikawa T. (1990). Preferential inhibition of elastin synthesis by epidermal growth factor in chick aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 168, 850-856. 10.1016/0006-291X(90)92399-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimani P. W., Holmes A. J., Grossmann R. E. and McGowan S. E. (2009). PDGF-Ralpha gene expression predicts proliferation, but PDGF-A suppresses transdifferentiation of neonatal mouse lung myofibroblasts. Respir. Res. 10, 119 10.1186/1465-9921-10-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler M. C., Loomis C. A., Zhao Z., Cushman J. C., Liu L. and Munger J. S. (2017). Sonic Hedgehog signaling regulates myofibroblast function during alveolar septum formation in murine postnatal lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 57, 280-293. 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0268OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannoy M., Slove S., Louedec L., Choqueux C., Journé C., Michel J.-B. and Jacob M.-P. (2014). Inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation: a new strategy to stimulate elastogenesis in the aorta. Hypertension 64, 423-430. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cras T. D., Hardie W. D., Deutsch G. H., Albertine K. H., Ikegami M., Whitsett J. A. and Korfhagen T. R. (2004). Transient induction of TGF-alpha disrupts lung morphogenesis, causing pulmonary disease in adulthood. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 287, L718-L729. 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Hu L., Xiao J., Chen H., Li J. T., Bellusci S., Delanghe S. and Minoo P. (2005). Wnt5a regulates Shh and Fgf10 signaling during lung development. Dev. Biol. 287, 86-97. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li A., Li M., Xing Y., Chen H., Hu L., Tiozzo C., Anderson S., Taketo M. M. and Minoo P. (2009). Stabilized beta-catenin in lung epithelial cells changes cell fate and leads to tracheal and bronchial polyposis. Dev. Biol. 334, 97-108. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li M., Li S., Xing Y., Yang C.-Y., Li A., Borok Z., De Langhe S. and Minoo P. (2015). Progenitors of secondary crest myofibroblasts are developmentally committed in early lung mesoderm. Stem Cells 33, 999-1012. 10.1002/stem.1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Herriges J. C., Chen L., Mecham R. P. and Sun X. (2017). FGF receptors control alveolar elastogenesis. Development 144, 4563-4572. 10.1242/dev.149443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Bernau K., Sandbo N., Gu J., Preissl S. and Sun X. (2018). Pdgfra marks a cellular lineage with distinct contributions to myofibroblasts in lung maturation and injury response. eLife 7, e36865 10.7554/eLife.36865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P., Karlsson L., Hellstrom M., Gebre-Medhin S., Willetts K., Heath J. K. and Betsholtz C. (1997). Alveogenesis failure in PDGF-A-deficient mice is coupled to lack of distal spreading of alveolar smooth muscle cell progenitors during lung development. Development 124, 3943-3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Rich C. B., Buczek-Thomas J. A., Nugent M. A., Panchenko M. P. and Foster J. A. (2003). Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor regulates elastin and FGF-2 expression in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 285, L1106-L1115. 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscertales M., Nicolaou F., Jeanne M., Longoni M., Gould D. B., Sun Y., Maalouf F. I., Nagy N. and Donahoe P. K. (2016). Type IV collagen drives alveolar epithelial-endothelial association and the morphogenetic movements of septation. BMC Biol. 14, 59 10.1186/s12915-016-0281-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S. E. and McCoy D. M. (2011). Fibroblasts expressing PDGF-receptor-alpha diminish during alveolar septal thinning in mice. Pediatr. Res. 70, 44-49. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31821cfb5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S. E. and McCoy D. M. (2014). Regulation of fibroblast lipid storage and myofibroblast phenotypes during alveolar septation in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 307, L618-L631. 10.1152/ajplung.00144.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S. E. and McCoy D. M. (2018). Neuropilin-1 and platelet-derived growth factor receptors cooperatively regulate intermediate filaments and mesenchymal cell migration during alveolar septation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 315, L102-L115. 10.1152/ajplung.00511.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQualter J. L., Yuen K., Williams B. and Bertoncello I. (2010). Evidence of an epithelial stem/progenitor cell hierarchy in the adult mouse lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1414-1419. 10.1073/pnas.0909207107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen P. J., Warburton D., Bu D., Zhao J.-S., Berger J. E., Minoo P., Koivisto T., Allen L., Dobbs L., Werb Z. et al. (1997). Impaired lung branching morphogenesis in the absence of functional EGF receptor. Dev. Biol. 186, 224-236. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan A. N., Brownfield D. G., Harbury P. B., Krasnow M. A. and Desai T. J. (2018). Single-cell Wnt signaling niches maintain stemness of alveolar type 2 cells. Science 359, 1118-1123. 10.1126/science.aam6603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A. and Lonai P. (1992). Platelet-derived growth factor-A and its receptor are expressed in separate, but adjacent cell layers of the mouse embryo. Development 115, 1045-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panos R. J., Patel R. and Bak P. M. (1996). Intratracheal administration of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor stimulates rat alveolar type II cell proliferation in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 15, 574-581. 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.5.8918364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti A. C., Ahmed A. M., Roberts J. D. Jr and Kelleher C. M. (2014). A novel in vitro model to study alveologenesis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 50, 459-469. 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0056OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plopper C. G., St George J. A., Read L. C., Nishio S. J., Weir A. J., Edwards L., Tarantal A. F., Pinkerton K. E., Merritt T. A., Whitsett J. A. et al. (1992). Acceleration of alveolar type II cell differentiation in fetal rhesus monkey lung by administration of EGF. Am. J. Physiol. 262, L313-L321. 10.1152/ajplung.1992.262.3.L313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. R., Dahlhoff M., Herbach N., Renner-Mueller I., Dalke C., Puk O., Graw J., Wanke R. and Wolf E. (2005). Betacellulin overexpression in transgenic mice causes disproportionate growth, pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome, and complex eye pathology. Endocrinology 146, 5237-5246. 10.1210/en.2005-0418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui S., Fang M., Ni B., Lu D., Martin B. and Maudsley S. (2012). Central role of the EGF receptor in neurometabolic aging. Int J Endocrinol 2012, 739428 10.1155/2012/739428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. (1997). The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development 124, 2691-2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproul E. P. and Argraves W. S. (2013). A cytokine axis regulates elastin formation and degradation. Matrix Biol. 32, 86-94. 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandjord T. P., Clark J. G., Guralnick D. E. and Madtes D. K. (1995). Immunolocalization of transforming growth factor-alpha, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and EGF-receptor in normal and injured developing human lung. Pediatr. Res. 38, 851-856. 10.1203/00006450-199512000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibeault D. W., Mabry S. M., Ekekezie I. I., Zhang X. and Truog W. E. (2003). Collagen scaffolding during development and its deformation with chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 111, 766-776. 10.1542/peds.111.4.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan A. E., Brumwell A. N., Xi Y., Gotts J. E., Brownfield D. G., Treutlein B., Tan K., Tan V., Liu F. C., Looney M. R. et al. (2015). Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature 517, 621-625. 10.1038/nature14112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicencio A. G., Lee C. G., Cho S. J., Eickelberg O., Chuu Y., Haddad G. G. and Elias J. A. (2004). Conditional overexpression of bioactive transforming growth factor-beta1 in neonatal mouse lung: a new model for bronchopulmonary dysplasia? Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 31, 650-656. 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0092OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel D. P., Taylor D. G., Albertine K. H., Keating M. T. and Li D. Y. (2000). Impaired distal airway development in mice lacking elastin. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 23, 320-326. 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.3906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zepp J. A., Zacharias W. J., Frank D. B., Cavanaugh C. A., Zhou S., Morley M. P. and Morrisey E. E. (2017). Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell 170, 1134-1148.e1110. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.