Abstract

Objectives

Examine correlates of initiation of e-cigarette use among smokers and determine the impact of e-cigarette use on cessation among smokers in a national U.S. consumer panel.

Methods

This study used the Nielsen Homescan Panel data from 2011 to 2013, augmented with state-specific measures of tobacco control activities, to examine 1) correlates of single and repeat e-cigarette purchasing among panelists currently purchasing cigarettes; and 2) correlates of “cessation”. Participating panelists scanned all retail purchases, and Nielsen recorded over 3 million product types. The key explanatory variable for cessation was e-cigarette purchase. Parallel analysis was conducted for conventional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) purchase. Cessation was defined as no purchases for at least 6 months and no subsequent purchases until the end of 2013. Analysis was conducted in 2015. E-cigarettes tracked by Nielsen during this period were cig-a-like products resembling tobacco cigarettes in appearance.

Results

Single e-cigarette purchase was associated with whether the panelist resided in a single person male household and bought a higher volume of cigarettes. Repeat purchase was associated with higher state cigarette taxes, less stringent state public smoke-free policies, lower cigarette prices, and more frequent cigarette purchasing. Cessation was associated with repeat e-cigarette purchasing, repeat NRT purchasing, younger age, lower monthly cigarette volume, less frequent purchasing of cigarettes, less recent cigarette purchase at baseline, and single e-cigarette purchase before baseline.

Conclusions

Both individual and policy variables were associated with e-cigarette use. Repeat e-cigarette purchase was associated with cigarette purchase discontinuation, as were various smoking intensity measures.

INTRODUCTION

There are limited conclusive data about which smokers are most likely to use e-cigarettes and whether e-cigarettes help or hinder cessation efforts. This study used an observational, longitudinal cohort design to examine which cigarette smokers purchase e-cigarettes – either experimentally or repeatedly – and the potential harm reduction impact of e-cigarettes on smokers by following a cohort of smokers over time.

The first important questions to address are: which smokers experiment with e-cigarettes and which are likely to become regular users of e-cigarettes? Answering these questions requires documenting differences in smoking behaviors among smokers. The type (e.g., menthol vs. non-menthol), price, and volume of cigarettes consumed at baseline might correlate with e-cigarette initiation and may impact the likelihood of continued use of e-cigarettes. For example, heavy smokers may be more likely to become intensive e-cigarette users than light smokers (1).

Additionally, understanding one’s motivation for using e-cigarettes and potentially quitting them is important. One study (2) noted that “curiosity” was the most commonly reported reason for initially trying e-cigarettes and that the most common reason for discontinuing e-cigarette use was that participants were “just experimenting” with them. Another study (3) documented that the most common reasons current and former smokers used e-cigarettes were for harm reduction and cessation. The most common reason for discontinued e-cigarette use among current smokers was because they were using other tobacco products, while the most common reason for discontinued e-cigarette use among former smokers was because they quit the use of all nicotine/tobacco (3). These findings suggest that indicators regarding motivation to quit smoking, such as prior NRT purchasing or previous gaps in cigarette purchase (potentially marking prior quit attempts), may be important correlates of e-cigarette initiation and regular use. Prior research has found that e-cigarette users report a higher number of previous quit attempts and intention to quit (4).

From a broader socioecological perspective, little is known about the impact of the tobacco control environment on initiation and continued use of e-cigarettes. For example, stricter policies could promote denormalization of tobacco and nicotine use altogether or promote the use of e-cigarettes in order to facilitate cessation. Accounting for these contextual findings may provide a more comprehensive account of how these factors might impact e-cigarette use over time.

In terms of the effect of e-cigarette use on smoking cessation, findings have been mixed. Two cohort studies found that e-cigarette use was negatively associated with cessation (5,6). Another six cohort studies found no significant association between e-cigarette use and cessation (7–12). Lastly, two studies documented that certain types of e-cigarette use were associated with cessation. A UK study found that daily tank users had increased odds of cessation, nondaily cig-a-like users have decreased odds, and all others demonstrated no difference in odds of cessation from nonusers of e-cigarettes (13). Another study of smokers in the US cities of Dallas and Indianapolis from 2011–2014 found an increase in the odds of smoking cessation among intensive e-cigarette users but no effect among intermittent e-cigarette users (1). These findings indicate that quantifying and characterizing e-cigarette use is important.

Given disparate findings reported by these prior observational studies, attention must be paid to the potential reasons for these differences. First is the timing and frequency of assessments. Some studies measure e-cigarette use only at baseline (5,6,8,9). If a study focuses on a cohort that is smoking at baseline and measures e-cigarette use at baseline only, ex-smokers who experienced an e-cigarette-associated quit pre-baseline would be excluded, biasing the results (14). Others measure e-cigarette use only at follow up, which limits the ability to determine sequencing of events in some cases (7,10,11). Second, some studies distinguished between different types of e-cigarette users (1,8,13), while others did not (5–7,9–12). This is important for two reasons: 1) experimenters versus more intensive users may have different characteristics at baseline (1,2); and 2) as with NRT, the causal impact of e-cigarette use on cessation is likely low among those that only briefly experiment with them. Greater attention must be given to understanding the characteristics of smokers who use e-cigarettes as well as characteristics of their use.

Given the aforementioned literature, the aims of the current study were: 1) to examine correlates of single and repeat e-cigarette purchasing among panelists that consistently purchasers cigarettes at baseline, and 2) to identify whether e-cigarette purchasing is associated with tobacco cigarette smoking cessation (defined as no purchases for at least 6 months and no subsequent purchases until the end of 2013) in a longitudinal national U.S. consumer panel. All household purchases were scanned by the panelists under study. Nielsen then keeps a record of the scanned purchases that match a database of over 3 million UPC codes including over 400 e-cigarette products from 49 different brands. In support of the study aims, we also examined whether cigarette purchase discontinuation was concurrent with the initiation of e-cigarette purchasing. Lastly, we presented trends in NRT purchasing to assess whether the growth in e-cigarette purchases reduced the amount of households purchasing NRT.

METHODS

The consumer purchasing data for our study, conducted in 2015, were derived from the Nielsen Homescan Panel. This dataset provides a record of consumer packaged goods purchases for a national panel of U.S. households. Consumers opted into this panel by applying, at which point they were added to a waiting list until a spot that matched their “demographic profile” opened up. At that point, panelists were sent a scanning device that they used to scan all household purchases. Nielsen households earned “points” by scanning items that are redeemable for prizes. Nielsen recorded the date and time of each purchase along with the price of each item.

Nielsen did not record all products that were scanned. In 2013, Nielsen tracked over 3 million products, including over 400 e-cigarette products across 49 distinct e-cigarette brands. However, all e-cigarette products tracked were either disposable or refillable cig-a-like products. Tank-style e-cigarettes and e-liquid purchases were not tracked during this period, and so many purchases from vape shops and online were not recorded by Nielsen.

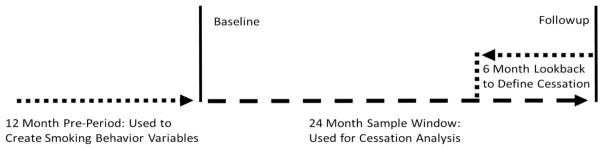

A sample of cigarette purchasers was constructed from the Nielsen panel. Households that had gaps of over 180 days between cigarette purchases were excluded from the sample. This was because “cessation” is a key study outcome and is defined by prolonged discontinuation of cigarette purchasing, and one cannot confidently ascertain whether an intermittent cigarette purchaser has changed their purchase behavior in a meaningful way. The effective “baseline” of the sample period was the beginning of 2012, with “follow up” at the end of 2013. Data from 2011 were used to both initiate a set of smoking behavior variables pre-baseline and to verify that a household had previously purchased cigarettes at baseline. Figure 1 shows the timeline of the pre-baseline period and the study observation window. The sample of smoking households was filtered to include only households who were in the sample in 2011 (N=62,092), remained through 2013 (N=43,828), and bought cigarettes at some point (25.2%, N=11,060). The sample was further restricted to households who: 1) purchased at least four cigarette packs between 2011 and 2013 (N=7,159); 2) made at least two cigarette purchases before baseline (in 2011) and at least one cigarette purchase after baseline (in 2012 or 2013, N=4,619); and 3) made consistent enough purchases that there are no gaps of greater than 180 days between purchases (N=2,868). Households with nonsensical price data (priced below tax level or above $20 per pack) were also removed, leaving a final analytic sample of 2,854 panelists.

Figure 1.

Study Timeline

Measures

Outlined below are the variables included in this analysis.

Smoking Cessation

The primary outcome for the second study aim was tobacco cigarette smoking cessation. Panelists were categorized to have “quit” if they did not purchase a pack of cigarettes for at least 180 days at any point during the observational window and did not purchase cigarettes again subsequently until the end of the observation window.

E-Cigarette Use

E-cigarette purchase was the primary outcome for the first study aim and the primary explanatory variable of interest for the second aim. E-cigarette purchasing households were stratified into single purchasers and repeat purchasers, following other studies that have found different motivations (2) and effects (1,8,13) between experimenters versus more intensive users.

For the analyses focusing on cessation, e-cigarette purchasing was also split into pre-baseline purchases (2011) and post-baseline purchases (2012–13), depending on when a panelist initiated e-cigarette purchasing. Note that a repeat purchasing household that initiated in 2011 was categorized as a pre-baseline repeat purchaser whether or not they continued using after baseline. This was done to accurately capture the prospective effect of e-cigarette purchase without ignoring past purchases or erroneously treating past purchasers as never-purchasers. E-cigarette purchases made in the last 180 days of 2013 were excluded from cessation analyses because there were insufficient data to prospectively follow these households for 180 days in order to determine whether a cessation had occurred.

NRT Use

Households that purchased NRT were stratified into single and repeat purchasers. Although this construction mirrors that of the e-cigarette use variables, the meaning of single NRT purchase may be different because a single purchase may include an entire recommended schedule for NRT. As with e-cigarettes, NRT use is also split into mutually exclusive pre-baseline and post-baseline purchasing categories. A repeat purchasing household that initiated in 2011 was categorized as a 2011 repeat purchaser whether or not they continued using into 2012 or 2013. Purchases during the final 180 days were excluded for the cessation analysis paralleling the treatment of e-cigarette purchases.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Precision regarding sociodemographics is limited because the panel operates at the level of the household. Age, race/ethnicity, household composition, and household income level were included. Specifically, either the age of single adult household members or the average age of the heads of household in multiple adult households was used. Exploratory analyses indicated that quit rates among Black panelists were significantly different from other races, and so race/ethnicity was categorized as Black versus other races. Hispanic ethnicity was included as well, along with variables for single male, single female, and multiple adult households.

State Tobacco Control Environment

Individual consumer information was augmented with data on state-level tobacco control funding, cigarette excise taxes, and smoke-free restrictions per the US Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) System. The variable for % CDC control funding was defined as the state’s level of funding divided by funding recommended by CDC. To assess smoke-free restrictions, each smoker was matched to their respective state’s level of smoke-free olicies in six venues – restaurants, bars, government workplaces, private workplaces, multi-unit housing common areas, and multi-unit housing living areas. In each venue, smoke-free restrictions were assigned one of three values: 0 for no restriction, .5 for partial, and 1 for a complete. We took the average of the smoke-free restrictions across bars, restaurants, workplaces, and homes. Cigarette excise taxes were defined as the state level of cigarette taxes.

Purchasing Characteristics

Purchase-related variables were calculated from pre-baseline data to prevent reverse causal effects of e-cigarette or NRT purchase after baseline. These variables include menthol (the only legal flavored cigarette in the US), 20-pack price, monthly cigarette volume, purchase frequency, and recency. Menthol purchasing was operationalized based on whether at least 50% of a participants’ cigarette spending was allocated to menthol cigarettes. 20-Pack price was defined as the average price paid per pack. Monthly cigarette volume was calculated as the number of packs purchased per month. Purchase frequency was operationalized as the average number of days between purchases. Recency was operationalized as the gap in time between baseline and the most recent purchase before baseline.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of participant baseline characteristics were conducted. Bivariate analyses were conducted examining correlates of single and repeat e-cigarette purchase at any point from 2011–13. For continuous variables, statistical significance was assessed using ordered logistic regression. For categorical variables, a standard Chi-square test was used. Next, a multinomial logistic regression was used to determine correlates of single and repeat e-cigarette purchase in 2012 or 2013. After that, a bivariate analysis was conducted examining correlates of cessation in 2012–13 (using bivariate logistic regression). Binary logistic regression was used for the multivariable analyses, jointly examining all correlates of cessation. Following the cessation analysis, an investigation was undertaken to determine whether quitting was occurring at or around first purchase of e-cigarettes or NRT. Lastly, an exploration of whether e-cigarette purchases appeared to displace NRT purchases in this population was conducted. All statistical models were estimated using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

Household Characteristics

The average age of the heads of household was 58.86 years old (SD=9.72) and was 10.65% Black, 84.37% White, and 3.50% Hispanic. Overall, 73.09% lived in multiple adult households; the average income was $47,926 (SD=$27,487; Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate analyses examine predictors of cessation among consistent smokers

| Variable | All Consistent Smokers | No Cessation | Cessation | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N=2854 | N=2370 | N=484 | |||||

| M or N | SD or % | M or N | SD or % | M or N | SD or % | ||

| Sociodemographics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age (SD) | 58.86 | 9.72 | 59.18 | 9.51 | 57.27 | 10.55 | <0.001 |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| Black | 304 | 10.65% | 262 | 11.05% | 42 | 8.68% | 0.122 |

| White | 2408 | 84.37% | 1982 | 83.63% | 426 | 88.02% | 0.015 |

| Asian | 30 | 1.05% | 27 | 1.14% | 3 | 0.62% | 0.307 |

| Other | 112 | 3.92% | 99 | 4.18% | 13 | 2.69% | 0.124 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 100 | 3.50% | 82 | 3.46% | 18 | 3.72% | 0.778 |

| Non-Hispanic | 2754 | 96.50% | 2288 | 96.54% | 466 | 96.28% | 0.778 |

| Household Composition (%) | |||||||

| Single female | 519 | 18.19% | 443 | 18.69% | 76 | 15.70% | 0.120 |

| Single male | 249 | 8.72% | 213 | 8.99% | 36 | 7.44% | 0.271 |

| Multiple adults | 2086 | 73.09% | 1714 | 72.32% | 372 | 76.86% | 0.040 |

| Income (SD) | $47,926 | $27,487 | $47,725 | $27,431 | $48,909 | $27,763 | 0.388 |

|

| |||||||

| State Tobacco Control Environment | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| % CDC control funding (SD) | 17.61% | 13.68% | 17.55% | 13.73% | 17.89% | 13.46% | 0.621 |

| State cigarette tax (SD) | $1.28 | $0.82 | $1.27 | $0.82 | $1.33 | $0.81 | 0.132 |

| Smoke-free policy index (SD) | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.055 |

|

| |||||||

| Smoking Characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Menthol (%) | 925 | 32.41% | 775 | 32.70% | 150 | 30.99% | 0.464 |

| 20-Pack price (SD) | $4.92 | $1.40 | $4.91 | $1.38 | $4.97 | $1.50 | 0.391 |

| Monthly cigarette volume (SD) | 21.28 | 20.76 | 22.77 | 21.24 | 14.00 | 16.43 | <0.001 |

| Purchase frequency (SD) | 16.60 | 18.29 | 14.54 | 15.23 | 26.69 | 26.75 | <0.001 |

| Recency (SD) | 16.35 | 23.39 | 14.62 | 21.19 | 24.80 | 30.72 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| E-cigarette and NRT Purchasing | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| E-cigarette purchases (%) | |||||||

| Never | 2567 | 89.94% | 2136 | 90.13% | 431 | 89.05% | 0.919 |

| Single, 2011 | 12 | 0.42% | 7 | 0.30% | 5 | 1.03% | 0.022 |

| Repeat, 2011 | 19 | 0.67% | 15 | 0.63% | 4 | 0.83% | 0.633 |

| Single, 2012–13 | 117 | 4.10% | 103 | 4.35% | 14 | 2.89% | 0.142 |

| Repeat, 2012–13 | 139 | 4.87% | 109 | 4.60% | 30 | 6.20% | 0.136 |

| NRT purchases (%) | |||||||

| Never | 2540 | 89.00% | 2126 | 89.70% | 414 | 85.54% | 0.004 |

| Single, 2011 | 53 | 1.86% | 42 | 1.77% | 11 | 2.27% | 0.457 |

| Repeat, 2011 | 103 | 3.61% | 84 | 3.54% | 19 | 3.93% | 0.682 |

| Single, 2012–13 | 76 | 2.66% | 57 | 2.41% | 19 | 3.93% | 0.058 |

| Repeat, 2012–2013 | 82 | 2.87% | 61 | 2.57% | 21 | 4.34% | 0.034 |

Note: M is the mean, N is the count, SD is the standard deviation around the mean, % is the share of the total sample represented by the count

E-Cigarette Purchasing

Bivariate analyses indicated that e-cigarette purchase was correlated with lower levels of smoke-free policies (P=0.025), lower cigarette prices (P<0.001), higher monthly cigarette volume (P<0.001), higher purchase frequency (P=0.004), greater likelihood of NRT purchasing (P=0.022), and greater likelihood of cessation. Single purchasers had the lowest quit rates and repeat purchasers having the highest (P=0.043; Supplementary Table 1). In multivariable analysis, single e-cigarette purchase was associated with whether the panelist resided in a single male household (P=0.046) and bought a higher volume of cigarettes (P=0.042; Table 2). Repeat purchase was associated with higher cigarette taxes (P=0.022), less stringent public smoke-free policies (P=0.014), lower cigarette prices (P=0.017), and more frequent cigarette purchasing (P=0.017).

Table 2.

Results from a multinomial logistic regression predicting single or repeat e-cigarette purchase among consistent smokers and binary logistic regression predicting smoking cessation

| Single E-cigarette Use | Repeat E-cigarette Use | Smoking Cessation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| CI | CI | CI | ||||||||||

| Variables | OR | Lower | Upper | p | OR | Lower | Upper | p | OR | Lower | Upper | p |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.099 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.400 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.001 |

| Black (vs. other) | 1.21 | 0.64 | 2.26 | 0.559 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 1.16 | 0.109 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 1.08 | 0.122 |

| Hispanic (vs. non) | 1.40 | 0.55 | 3.59 | 0.479 | 1.47 | 0.65 | 3.31 | 0.358 | 0.83 | 0.48 | 1.44 | 0.505 |

| Single female household (vs. multiple) | 1.41 | 0.85 | 2.34 | 0.187 | 1.34 | 0.84 | 2.15 | 0.224 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 1.05 | 0.106 |

| Single male household (vs. multiple) | 1.82 | 1.01 | 3.26 | 0.046 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.90 | 0.962 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 1.37 | 0.695 |

| Income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.490 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.142 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.999 |

| State Tobacco Control Environment | ||||||||||||

| % CDC control funding | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.578 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.152 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.867 |

| Cigarette tax | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.38 | 0.997 | 1.40 | 1.05 | 1.86 | 0.022 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.28 | 0.334 |

| Smoke-free policy index | 0.75 | 0.32 | 1.71 | 0.488 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.014 | 1.41 | 0.88 | 2.26 | 0.160 |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Menthol | 1.01 | 0.67 | 1.52 | 0.963 | 1.11 | 0.76 | 1.61 | 0.602 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 1.23 | 0.832 |

| 20-Pack price | 0.92 | 0.76 | 1.11 | 0.381 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.96 | 0.017 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.501 |

| Monthly cigarette volume | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.042 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.081 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | <.0001 |

| Purchase frequency | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.429 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.017 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | <.0001 |

| Recency | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.980 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.470 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.001 |

| NRT Purchase (vs. never) | ||||||||||||

| Single | 1.30 | 0.62 | 2.74 | 0.490 | 1.48 | 0.77 | 2.84 | 0.235 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Repeat | 1.45 | 0.74 | 2.84 | 0.283 | 1.45 | 0.80 | 2.65 | 0.224 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| E-cigarette purchases (vs. never) | ||||||||||||

| Single, 2011 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4.36 | 1.26 | 15.07 | 0.020 |

| Repeat, 2011 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.54 | 0.48 | 4.92 | 0.464 |

| Single, 2012–13 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.66 | 0.36 | 1.20 | 0.176 |

| Repeat, 2012–13 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.77 | 1.14 | 2.75 | 0.011 |

| NRT purchases (vs. never) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Single, 2011 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4.36 | 1.26 | 15.07 | 0.020 |

| Repeat, 2011 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.54 | 0.48 | 4.92 | 0.464 |

| Single, 2012–13 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.66 | 0.36 | 1.20 | 0.176 |

| Repeat, 2012–2013 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2.10 | 1.23 | 3.60 | 0.007 |

Cessation

Cessation was associated with younger age (P<0.001), being White (P=0.015), residing in a multiple-person household (P=0.040), purchasing fewer cigarettes per month (P<0.001), purchasing cigarettes less frequently (P<0.001), purchasing cigarettes less recently (P<0.001), making a single e-cigarette purchase before cessation (P=0.022), and making repeat NRT purchases after baseline (P=0.034; Table 1). In multivariable analyses (Table 2), repeat e-cigarette purchase (P=0.011) and repeat NRT purchase (P=0.007) after baseline were both associated with cessation. Younger age (P=0.001), lower monthly cigarette volume (P<0.001), less frequent purchasing of cigarettes (P<0.001), less recent cigarette purchase at baseline (P=0.001), and single e-cigarette purchase before baseline (P=0.020) were also associated with cessation.

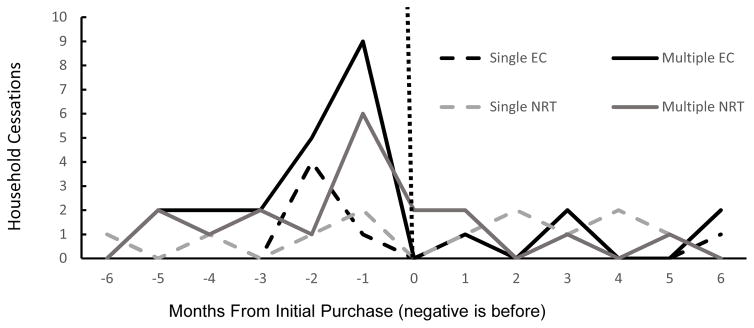

Figure 2 uses the time granularity of this dataset to show the time between the initial e-cigarette or NRT purchase and the final cigarette purchase. The final cigarette purchase over time is plotted, with the initial e-cigarette or NRT purchase considered to be time 0. There was a spike in final cigarette purchases close to e-cigarette or NRT initiation date. The precise date of cessation was likely to occur sometime after the final cigarette purchase date because the purchase may take several days or weeks to consume. Initial NRT purchase was most frequently within 1 month after the final cigarette purchase; and initial e-cigarette purchase was estimated at 1–2 months after final cigarette purchase.

Figure 2.

Temporal proximity of last cigarette purchase to first e-cigarette/NRT purchase

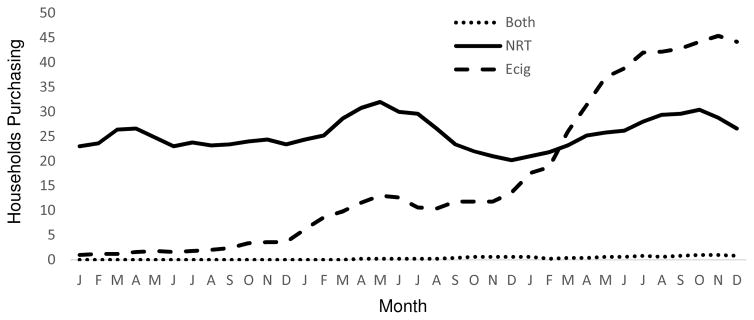

NRT Displacement

Figure 3 estimates how NRT purchasing was affected by the emergence of e-cigarettes. Overall, e-cigarettes did not appear to substantially displace NRT purchases. Although 16.5% of e-cigarette purchasers also purchased NRT, there was not an obvious reduction in the amount of NRT purchases over time

Figure 3.

Households Making E-cigarette and NRT purchases, Jan 2011 to Dec 2013

DISCUSSION

This study was the first cohort study using consumer purchase data to examine correlates of e-cigarette initiation and repeated purchase as well as the impact of e-cigarette purchase on cessation. The main finding was that repeat e-cigarette purchasing was associated with smoking cessation, while single e-cigarette purchase was not. Moreover, repeat e-cigarette purchase was associated with more frequent cigarette purchases before baseline, suggesting that these households have lower propensity to quit at baseline. However, multivariable analysis suggested significantly higher likelihood of quitting. It is important to interpret these findings with caution. This study design cannot discern causality. It is possible that repeat e-cigarette purchase selects for motivated smokers who may have quit regardless of e-cigarette use.

There are other findings related to cessation that are worth noting. All smoking intensity variables were associated with decreased odds of cessation. Although previous studies have examined the relationship between smoking cessation and over-the-counter NRT in real-world samples (15–17), previous looks at NRT in the Nielsen sample had not examined the impact on cessation (18). Cessation was associated with repeat NRT purchase. As in the case of e-cigarettes, we could not disentangle the degree to which NRT purchase selects for quit intention. Single e-cigarette purchase before baseline was also associated with cessation. There were only twelve single e-cigarette purchasing households before baseline, of which five quit after baseline, so this result may not hold outside of this sample. To the extent that the relationship found among these 12 smokers is meaningful, it might indicate a selection effect among smokers who chose to purchase e-cigarettes in 2011. It is difficult to identify a clear causal mechanism that would apply to single purchasers but not repeat purchasers. Such a mechanisms has yet to emerge in the e-cigarette literature.

Additionally, e-cigarette purchase was associated with smoking intensity measures, similar to prior findings (1). Specifically, higher volume smokers were more likely to make a single e-cigarette purchase, while more frequent cigarette purchasers were more likely to make repeat e-cigarette purchases. Repeat e-cigarette purchase was associated with lower per-pack cigarette cost, suggesting that e-cigarettes might appeal to more price-sensitive smokers. As for policy, some of the associations found between e-cigarette purchase and policy are intuitive (higher cigarette taxes were associated with repeat e-cigarette use, suggesting increased substitution where cigarette prices are higher). Others may be more surprising. The finding that higher levels of smoke-free policies were associated with lower rates of repeat e-cigarette purchase is interesting. This may be explained by cultural differences between states that pass more comprehensive smoke-free policies versus those lagging in that area. It may also be easier to vape indoors in states that do not have smoking bans, since the applicability of smoke-free policies to e-cigarettes was often not stipulated during this period.

Figure 2 underscores the need to pick up the change in e-cigarette or NRT purchase between baseline and follow up to avoid selecting out successful quits that occurred right as these products were initiated (14). It also suggests the possibility that e-cigarettes were more likely than NRT to be initiated in the midst of a quit attempt as opposed to the outset, perhaps as relapse prevention. The finding that e-cigarette purchases did not seem to displace NRT purchase (Figure 3) echoes findings from a UK sample (19).

The current study has important implications for research and practice. In research, characterization of e-cigarette types and usage patterns is necessary, especially with rapidly proliferating new product types (20). More detailed study of the interrelationships between quit intention, quit propensity, and e-cigarette purchase is also necessary to better control for selection effects. Additionally, other forms of verification beside purchase scanning are necessary in order to have more specific and precise measures of product usage. In practice, clinicians need better resources to aid them in discussions with patients about the state of the science regarding e-cigarettes and cessation.

Limitations

Limitations include the lack of ability to verify that households used the items that they purchased, including the possibility that households may have made purchases for non-household members. It is also possible that heavier smokers may have finished and disposed of cigarette packs before scanning or otherwise refrained from scanning cigarette purchases. This adds potential measurement error to measures of cigarette purchasing. Filtering out smokers who purchased intermittently mitigates this weakness. Similarly, some households may have received NRT directly from quit lines or healthcare providers, and so many households that are coded as non-NRT purchasers may in fact have used NRT. If these missing NRT users were more likely to have purchased e-cigarettes (as was the case with measured NRT purchasers), then the resultant confounding might create a bias toward a finding that e-cigarettes are associated with smoking cessation. Nielsen did not record all scanned products, most notably tank-style and e-liquid purchases. Previous studies have found cig-a-likes to have a lower association with smoking cessation than other product types (13).

In addition, data were collected at the household level, and it is not clear how many smokers lived in multi-person households. This may have biased cessation rates downward for both purchasers and non-purchasers of e-cigarettes because a multi-smoker household where one smoker discontinued cigarette purchases but the other did not was coded as a continuing cigarette purchaser. It is also possible that a nonsmoking household member was purchasing e-cigarettes rather than the smoking member. This would bias the results toward a finding that e-cigarettes are unrelated to quitting, either positively or negatively, because the smoker was not the one purchasing e-cigarettes as had been assumed. Also, there was a lack of psychosocial measures, particularly those related to quit intention and reasons for using e-cigarettes. An arbitrary determination of eligibility criteria, cessation outcome, e-cigarette usage variables, etc. was necessary although sensitivity to these decisions was tested and they did not impact the core conclusions. The older average age of this sample may not allow for generalizability to younger populations. The largely White non-Hispanic sample may not generalize to non-White populations. Moreover, Nielsen does not include a racial category for mixed race individuals or households, who may decide to mark “Other” when asked about their racial identity. Also, looking only at Nielsen participants who were willing to scan all of their purchases may limit generalizability. Some tobacco control policies were not included, such as vehicle bans, as there was little variability compared to the policies that were included.

Lastly, as in previous studies (21,22), the use of consumer purchase data required the construction of variables defined specifically for this analysis, most notably variables that served as proxies use of e-cigarettes, NRT, and tobacco smoking behaviors including cessation. Although this data does not rely on memory as in the case with self-report data, use of these proxies introduces potential measurement error of a different sort. Purchase data also makes it difficult to give a precise quit date for any smoker in the sample since the dataset only recorded the last date that a cigarette purchase was made. Depending on the size of that purchase and the smoking intensity of the household, the true cessation date could have been a month or more after the final purchase.

Conclusions

The key finding is that repeat e-cigarette purchasing was associated with discontinuation of cigarette purchasing in a cohort of mostly older smokers, as is the case with NRT. This design does not allow for causal conclusions about the effectiveness of e-cigarettes or NRT. Other results include that higher cigarette taxes and greater smoking intensity were associated with more e-cigarette use, while paying more per pack and facing stricter smoke-free policies were associated with less e-cigarette use. Further research is needed to add to these findings and inform policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our funders for their support. These results are Calculated (or Derived) based on data from The Nielsen Company (US), LLC and marketing databases provided by the Kilts Center for Marketing Data Center at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Information about the data and access are available at http://research.chicagobooth.edu/nielsen/

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1R21CA198455-01, PI: Berg; U01CA154282-01, PI: Kegler). The funders had no role in the analyses or interpretation of the study or its results.

Footnotes

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Contributorship Statement

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the research aims and analytic plan as well as the interpretation of the results. ZC and RH conducted the data analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. ML, YW, and CB contributed to the writing. CB finalized the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

No additional data available.

Ethics Statement

The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Disclaimer

Any views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their affiliated organizations.

References

- 1.Biener L, Hargraves JL. A Longitudinal Study of Electronic Cigarette Use Among a Population-Based Sample of Adult Smokers: Association With Smoking Cessation and Motivation to Quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 Feb 1;17(2):127–33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for Starting and Stopping Electronic Cigarette Use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014 Oct 3;11(10):10345–61. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg CJ. Preferred flavors and reasons for e-cigarette use and discontinued use among never, current, and former smokers. Int J Public Health. 2015 Nov;18:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0764-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutten LJF, Blake KD, Agunwamba AA, Grana RA, Wilson PM, Ebbert JO, et al. Use of E-Cigarettes Among Current Smokers: Associations Among Reasons for Use, Quit Intentions, and Current Tobacco Use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 Oct;17(10):1228–34. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grana RA, Popova L, Ling PM. A longitudinal analysis of electronic cigarette use and smoking cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 May;174(5):812–3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Delaimy WK, Myers MG, Leas EC, Strong DR, Hofstetter CR. E-Cigarette Use in the Past and Quitting Behavior in the Future: A Population-Based Study. Am J Public Health. 2015 Apr 16;105(6):1213–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Hyland A, Borland R, Yong H-H, et al. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Mar;44(3):207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, West R, McNeill A. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2015 Jul 1;110(7):1160–8. doi: 10.1111/add.12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borderud SP, Li Y, Burkhalter JE, Sheffer CE, Ostroff JS. Electronic cigarette use among patients with cancer: characteristics of electronic cigarette users and their smoking cessation outcomes. Cancer. 2014 Nov 15;120(22):3527–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson JL, Stanton CA, Cha S, Niaura RS, Luta G, Graham AL. E-Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation: Insights and Cautions From a Secondary Analysis of Data From a Study of Online Treatment-Seeking Smokers. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2015 Oct;17(10):1219–27. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gmel G, Baggio S, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen J-B, Studer J. E-cigarette use in young Swiss men: is vaping an effective way of reducing or quitting smoking? Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14271. doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JJ, Grana RA. E-Cigarette Use among Smokers with Serious Mental Illness. PLoS ONE [Internet] 2014 Nov 24;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113013. [cited 2016 Oct 18] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4242512/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J, Robson D, McNeill A. Associations Between E-Cigarette Type, Frequency of Use, and Quitting Smoking: Findings From a Longitudinal Online Panel Survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 Apr 20;:ntv078. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajek P, McRobbie H, Bullen C. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation. Lancet Respir Med. 2016 Jun;4(6):e23. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiffman S, Rolf CN, Hellebusch SJ, Gorsline J, Gorodetzky CW, Chiang Y-K, et al. Real-world efficacy of prescription and over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy. Addiction. 2002 May;97(5):505–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West R, Zhou X. Is nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation effective in the “real world”? Findings from a prospective multinational cohort study. Thorax. 2007 Nov;62(11):998–1002. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.078758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotz D, Brown J, West R. “Real-world” effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments: a population study. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2014 Mar;109(3):491–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiffman S, Hughes JR, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL. Persistent use of nicotine replacement therapy: an analysis of actual purchase patterns in a population based sample. Tob Control. 2003 Sep;12(3):310–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard E, Brown J, McNeill A, Michie S, West R. Has growth in electronic cigarette use by smokers been responsible for the decline in use of licensed nicotine products? Findings from repeated cross-sectional surveys. Thorax. 2015 Jul 24; doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206801. thoraxjnl-2015-206801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, Cummins SE, Gamst A, Yin L, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014 Jul 1;23(suppl 3):iii3–iii9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis M, Wang Y, Berg CJ. Tobacco control environment in the United States and individual consumer characteristics in relation to continued smoking: Differential responses among menthol smokers? Prev Med. 2014 Aug;65:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis M, Wang Y, Cahn Z, Berg CJ. An exploratory analysis of cigarette price premium, market share and consumer loyalty in relation to continued consumption versus cessation in a national US panel. BMJ Open [Internet] 2015 Nov 3;5(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008796. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4636604/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.