Abstract

The secreted Ly-6/uPAR related protein-1 (SLURP1) is an anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory peptide highly expressed by the mucosal epithelial cells. SLURP1 is abundantly expressed by the corneal epithelial cells and is significantly downregulated when these cells are transformed and adapted for culture in vitro. Here we studied the effect of overexpressing SLURP1 in Human Corneal Limbal Epithelial (HCLE) cells cultured in vitro. The expression of DSP1, DSG1, TJP1 and E-Cadherin was significantly upregulated in two different SLURP1-overexpressing HCLE cell (HCLE-SLURP1) clones. HCLE-SLURP1 cells also displayed a significant decrease in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-induced upregulation of (i) IL-8 from 7.4- to 2.9- and 2.1-fold, (ii) IL-1β from 4.9- to 3.9- and 2.9-fold, (iii) CXCL1 from 9- to 3.3- and 5.5-fold, and (iv) CXCL2 from 4.8- to 2.1- and 2.8-fold. ELISAs revealed a concomitant decrease in IL-8 levels in cell culture supernatants from 789 pg/ml in the control, to 503 and 352 pg/ml in HCLE-SLURP1 cells. Consistently, cytosolic IκB expression was elevated in HCLE-SLURP1 cells with a concurrent suppression of TNF-α-activated nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Collectively, these results elucidate the beneficial effects of SLURP1 in stabilizing the HCLE intercellular junctions and suppressing the TNF-α-induced upregulation of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing NF-κB nuclear translocation.

Keywords: Corneal Epithelium, SLURP1, TNF-α, NF-κB, Cell junctions

1. Introduction

The secreted Ly6/urokinase type plasminogen activator receptor related protein-1 (SLURP1) is an 88 amino acids peptide member of the leukocyte antigen-6 (Ly6) family that is structurally similar to snake venom neurotoxins with distinct disulfide bonding pattern between 10 cysteine residues [1,2]. Deletions or mutations in SLURP1 cause Mal-de-Meleda, an autosomal recessive palmoplantar keratopathy [3,4,5], features of which are recapitulated in the Slurpl-null mice [6]. SLURP1 serves as a ligand for α7 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) exerting antiproliferative effects on epithelial cells [7,8,9]. It is believed to fine-tune the physiologic regulation of keratinocyte functions through nAChR-mediated cholinergic pathways [10,11]. SLURP1 facilitates functional development of T cells, and suppresses TNF-α production by T-cells, IL-1 β and IL-6 secretion by macrophages, IFN-γ-induced upregulation of ICAM-1, and IL-8 secretion by human intestinal enterocytes by serving as an allosteric antagonist of α7-nAchR [8,12,13],

SLURP1 is expressed abundantly in the corneal epithelium (CE), moderately in other mucosal epithelia, and at a relatively low level in the immune cells and sensory neurons, and secreted into the tear film, saliva, sweat, urine and plasma [1,2,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. SLURP1 expression is markedly decreased in transformed cells suggesting that it protects against malignant transformation [20]. Consistently, SLURP1 can overcome the tumorigenic effect of tobacco-derived nitrosamine on immortalized oral epithelial cells in vitro and in nude mice in vivo [21,22]. Slurp1 is one of the most highly expressed transcripts in the mouse cornea [14,15]. Our previous studies demonstrated that SLURP1 contributes to the corneal immune privilege by serving as an immunomodulatory molecule. SLURP1 scavenges extracellular urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) [7,15,23], impedes with TNF-α-activated human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) tube formation [24] and suppresses neutrophil binding, chemotaxis, and transmigration through human umbilical vein endothelial cells [25]. Though these studies elucidated the anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory functions of SLURP1, the influence of SLURP1 on corneal epithelial cells where it is produced in abundance was not clear. In this report, we attempted to fill this gap by evaluating the effect of overexpressing SLURP1 on human corneal limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells cultured in vitro. Our results presented in this report elucidate the beneficial effects of SLURP1 on HCLE cells in stabilizing the intercellular junctions and suppressing the TNF-α-induced upregulation of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing nuclear translocation of NF-κB, the master regulator of inflammation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human donor corneas and cell culture

All studies with human tissues were conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki principles. Human corneas were sourced from donor corneal tissues rejected for transplants, following the procedures approved by the University of Pittsburgh Committee for Oversight of Research and Clinical Training Involving Decedents (CORID ID # 889; PI: Swamynathan). Generation of Human Corneal Limbal Epithelial (HCLE) cells expressing SLURP1 (HCLE-SLURP1) by lentiviral transduction of CMV promoter-SLURP1 expression cassette followed by blasticidin selection was described previously [7]. HCLE [26] and HCLE-SLURP1 cells were cultured in keratinocytes-serum free medium (KSFM) supplemented with calcium chloride (0.3 M), epidermal growth factor (0.2 ng/mL), and brain pituitary extract as earlier [7,26]. For studies with TNF-α treatment, medium was changed to KSFM with calcium chloride without epidermal growth factor (EGF) and brain pituitary extract for 16 hours before treating with TNF-α (10 ng/ml).

2.2. RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human donor corneas rejected for transplants or HCLE cells using EZ-10 mini-prep kit (Bio Basic Inc. Amherst, NY), cDNA was synthesized using Mouse Moloney Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) and QPCR assays performed in duplicate using SYBRGreen reagents (Applied Biosystems) and validated primers with TBP as endogenous control as described previously [25]. The oligonucleotide sequence of the primers used is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

2.3. Immunoblots, Immunofluorescent Staining and ELISAs

Details of the antibodies used are provided in Supplemental Table 2. Equal quantity of proteins as quantified by bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) were electrophoretically separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and subjected to immunoblot analysis, and imaged using an Odyssey Scanner (LiCor Technologies) as described earlier [25].

Immunofluorescent staining was employed for visualizing the differences in expression and subcellular localization of different proteins. Confluent or near confluent HCLE or HCLE-SLURP1 cells grown in 48 well plates were subjected to immunofluorescent staining and imaged using an Olympus IX81 confocal microscope (Center Valley, PA) as earlier [25].

To quantify IL-8 in culture supernatants, DuoSet ELISA development system for human IL-8 was used following the protocol suggested by the manufacturer (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN. Catalog # DY208–05). Supernatant was collected from HCLE and SLURP1-expressing clones treated with TNF-α (10ng/ml) for 4 hours.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Mean values from at least three independent replicates with standard error bars or representative data from an individual experiment with at least three similar replicates are presented here. Statistical significance was measured using Student’s t-test, and differences deemed statistically significant if p values are less than or equal to 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. SLURP1 is abundantly expressed in the human cornea and is significantly downregulated in HCLE cells cultured in vitro

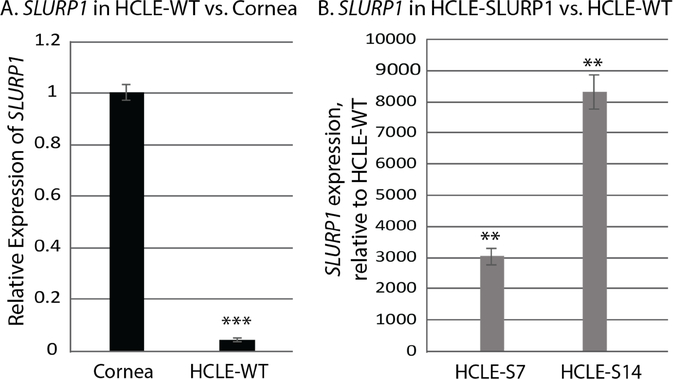

SLURP1, normally highly expressed in mucosal epithelial tissues, is downregulated in rapidly proliferating transformed cells derived from these tissues [7,8,9]. Consistent with these reports, SLURP1 was significantly downregulated in the HCLE cells to 4.3% of that in the human corneas (Fig. 1A). To determine the beneficial effects of high level of SLURP1 expression in CE cells, we lentivirally transduced HCLE cells with a CMV promoter-driven SLURP1 expression cassette and selected two different single-cell derived clones (HCLE-S7 am HCLE-S14) as described earlier [7]. QPCR revealed a significant increase in SLURP1 expressio in these cells compared with the wild type HCLE (HCLE-WT) cells (Fig. 1B). Thus, HCLE-WT HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells provide a good model to evaluate the effects of SLURP1 on CE cells and are employed in the rest of the experiments reported here.

Figure 1. SLURP1 expression in the human cornea, HCLE and HCLE-SLURP1 cells.

A). Comparison of SLURP1 expression in human cornea with that in the HCLE-WT cells by QPCR. B). Comparison of SLURP1 expression in HCLE-SLURP1 cells relative to that in the HCLE-WT cells (n=3; mean +/− standard error of mean shown). Statistical significance (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.005 and ***, p<0.005) is indicated.

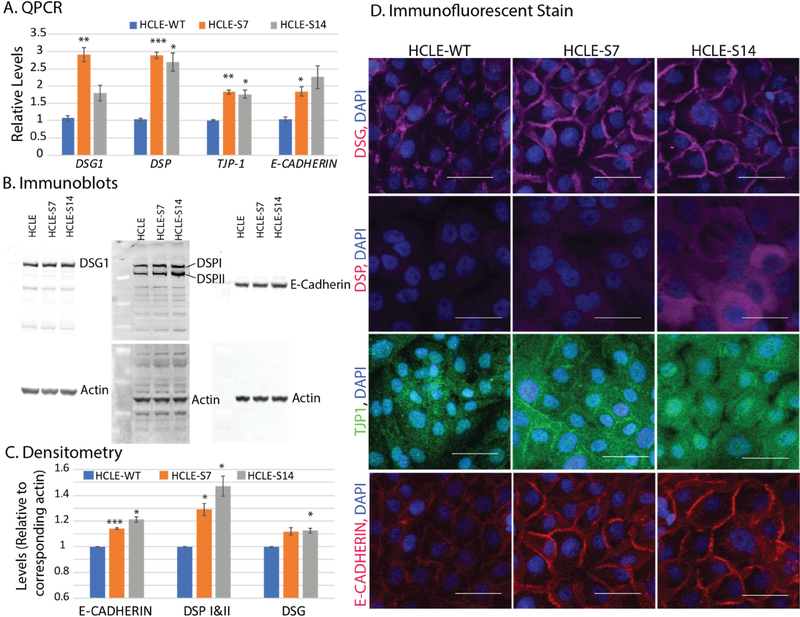

3.2. Overexpression of SLURP1 in HCLE cells stabilizes HCLE cell junctions

Considering that Slurp1-null mice develop palmoplantar keratoderma with water barrier defect [6], we tested if overexpression of SLURP1 stabilizes the HCLE cell junctions. QPCR revealed significantly increased expression levels of DSG1, DSP, TJP1 and E-Cadherin transcripts in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells relative to that in HCLE-WT (Fig. 2A). Immunoblots and their densitometric measurements using corresponding β-actin signal intensities confirmed the increased expression levels of DSG1, DSP-I, DSP-II, and E-Cadherin proteins in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells (Fig. 2B and 2C). Consistent with these results, immunofluorescent stain revealed sharply increased expression of DSG1, DSP, TJP1 and E-CADHERIN at cell junctions of confluent HCLE-S7, and HCLE-S14 compared with the HCLE-WT cells (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that SLURP1 stabilizes the epithelial cell junctional complexes and consequently, their barrier function.

Figure 2. SLURP1 stabilizes HCLE cell junctions.

A). Expression levels of DSG1, DSP, TJP1 and E-Cadherin transcripts in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells relative to that in HCLE-WT, measured by QPCR (n=6). B). Expression levels of DSG1, DSP-I, DSP-II, and E-Cadherin in HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells, detected by immunoblots (n=3; representative images shown). The blots were re-probed with anti-β-actin antibody for normalization of loading. C). Densitometry showing relative levels of E-CADHERIN, DSP-I and DSP-II, and DSG1, normalized to actin levels in corresponding blots (n=3; mean +/− standard error of mean shown). Statistical significance of the difference in expression levels between HCLE-S7 or HCLE-S14 and HCLE-WT is indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.005 and ***, p<0.005). D). Immunofluorescent stain for DSG1, DSP, TJP1 and E-CADHERIN in confluent HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7, and HCLE-S14 cells (n=3; representative images shown). Scale bar: 50 μm.

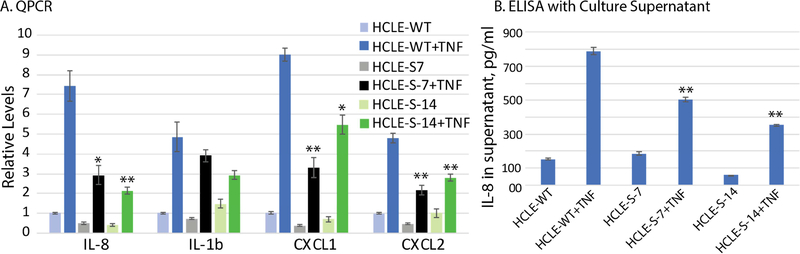

3.3. Overexpression of SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2

As our previous studies identified an immunomodulatory role for SLURP1 [7,15,23,24,25], next we evaluated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells. Sub-confluent HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells were stimulated with TNF-α for 4h, total RNA isolated and IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts quantified by QPCR. Though TNF-α stimulated the expression of these cytokines in all cell types, overexpression of SLURP1 resulted in a significant suppression of the TNF-α-stimulated expression of IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 compared with the HCLE-WT cells (Fig. 3A). Consistent with these results, ELISAs using cell culture supernatants revealed that SLURP1 overexpression resulted in a significant suppression of the TNF-α-stimulated secretion of IL-8 from 789 pg/ml in HCLE-WT, to 503 and 352 pg/ml in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells, respectively (Fig. 3B). Collectively, these results suggest that SLURP1 suppresses the TNF-α-stimulated production of inflammatory cytokines in HCLE cells.

Figure 3. SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced upregulation of IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2.

A). QPCR quantification of cytokine expression. HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells were stimulated with TNF-α for 4h, total RNA isolated and IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts quantified by QPCR (n=6; mean +/− standard error of mean shown). B). ELISA for IL-8 in cell culture supernatants. Cell culture supernatants from unstimulated and TNF-α-stimulated HCLE-WT and HCLE-SLURP1 cells were subjected to ELISA for IL-8 (n=3; mean +/− standard error of mean shown). Statistical significance of the response of HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 to TNF-α, compared with that of HCLE-WT is indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.005 and ***, p<0.005).

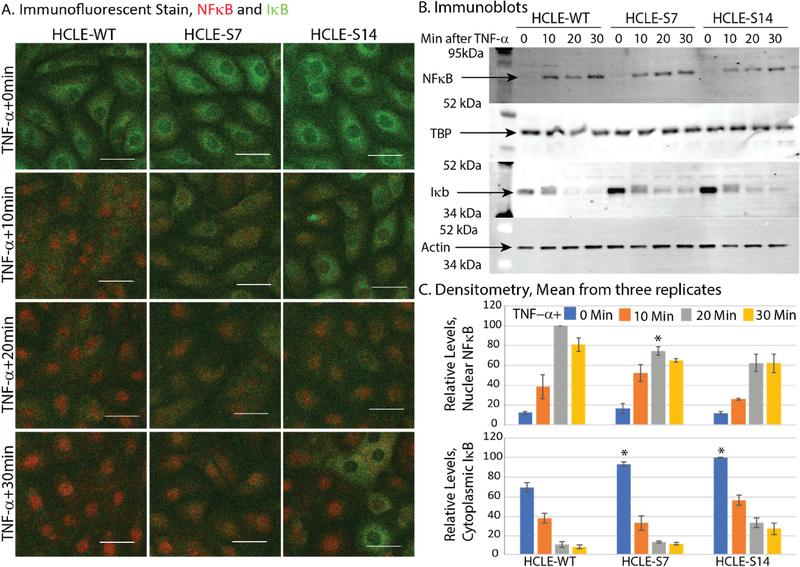

3.4. SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB in HCLE-SLURP1 cells by stabilizing cytosolic IκB

Given that NFκB is a master regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokine production [27,28], we next evaluated NFκB activity in these cells at different time points after stimulating with TNF-α. Immunofluorescent stain with anti-p65 antibody revealed that TNF-α-stimulation resulted in efficient nuclear localization of NFκB within 30 minutes in HCLE-WT which appeared to be incomplete in HCLE-S7 or HCLE-S14 cells (Fig. 4A). These differences were much more striking at 10 and 20 minutes after TNF-α-treatment (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescent stain also revealed relatively higher IκB expression in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cytoplasm compared with the control HCLE-WT (Fig. 4A). To further confirm this, we performed immunoblots with nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates prepared from HCLE-WT, HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells stimulated with TNF-α for 0, 10, 20 and 30 minutes with anti-NFκB and anti-IκB antibodies. Consistent with the lower level of NFκB activation in HCLE-SLURP1 cells suggested by immunofluorescent stain, immunoblots revealed decreased quantity of NFκB in nuclear lysate, with a concomitant increase in the IκB levels in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 compared with the HCLE-WT cytosol (Fig. 4B). Immunoblots with the nuclear and cytosolic fractions were re-probed with anti-TATA binding protein (TBP) and anti-β-actin antibody, respectively, for normalization of loading. Densitometric quantification of immunoblots confirmed relatively lower levels of nuclear NFκB (normalized to corresponding TBP levels) and higher levels of cytosolic IκB (normalized to corresponding β-actin levels) in HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 cells compared with HCLE-WT (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB by stabilizing cytosolic IκB.

Figure 4. SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB by stabilizing cytosolic IκB in HCLE cells.

A). Immunofluorescent stain with anti-p65 antibody revealed that TNF-α-stimulation resulted in rapid nuclear localization of NFκB (red) within 30 minutes in HCLE-WT, which was suppressed in HCLE-SLURP1 cells. Concomitantly, IκB (green) expression was relatively more intense in HCLE-SLURP1 cytoplasm compared with the HCLE-WT cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. B). Immunoblots. Nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates were prepared from HCLE-WT and HCLE-SLURP1 cells stimulated with TNF-α for 0, 10, 20 and 30 minutes, and probed with anti-NFκB or anti-IκB antibodies, respectively. Immunoblots with the nuclear and cytosolic fractions were re-probed with anti-TATA binding protein (TBP), and anti-β-actin antibody, respectively, for normalization of loading. C). Densitometry of immunoblots. Relative levels of nuclear NFκB (normalized to corresponding TBP levels) and cytosolic IκB (normalized to corresponding β-actin levels) are shown (n=3; mean +/− standard error of mean shown). Statistical significance of the response of HCLE-S7 and HCLE-S14 to TNF-α, compared with the response of HCLE-WT at the same time point is indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.005 and ***, p<0.005).

4. Discussion

Previously, we demonstrated that SLURP1 contributes to corneal angiogenic- and immune-privilege in healthy corneas where it is highly expressed [7,15,23,24,25]. Though SLURP1 is abundantly expressed in vivo by the corneal epithelial cells, it is significantly downregulated when these cells are transformed and adapted for culture in vitro. In this report, we demonstrate that SLURPl-overexpressing HCLE cells display (i) stabilization of cell junctions as evidenced by elevated expression of DSP1, DSG1, TJP1 and E-Cadherin, (ii) decrease in TNF-α-induced upregulation of IL-8, IL-1β, CXCL1 and CXCL2, and (iii) elevated expression of cytosolic IκB with a concurrent suppression of TNF-α-activated nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Collectively, these results elucidate the beneficial effects of SLURP1 on HCLE cells in stabilizing the intercellular junctions and suppressing the TNF-α-induced upregulation of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing NF-κB nuclear translocation.

Mucosal epithelial barrier safeguards the body against external toxins, antigens and infectious agents at multiple sites including the ocular surface. The CE barrier function, like that of other mucosal epithelial tissues, depends on protein complexes including desmosomes, adherens junctions and tight junctions that mechanically link adjacent cells and seal the intercellular space [29,30]. The data presented in this report provide evidence that SLURP1 stabilizes the CE barrier function by promoting the expression of desmosomal DSG and DSP, adherens junction component E-Cadherin, and tight junction component TJP1. These results are consistent with the loss of water barrier function in Slurp1-null mice [6], and maintenance of skin and CE barrier function by KLF4 [31,32] which also promotes SLURP1 expression [23].

Our previous work [7,15,23,24,25] added SLURP1 to a class of molecules that regulate corneal angiogenic- and immune-privilege by impeding with angiogenic and inflammatory response to mild insults and are down-regulated in response to acute insults allowing protective inflammation [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Many of these molecules feed into the NFκB pathway that plays a key role in inflammation [27,28]. In resting cells, cytosolic IκB inhibits NFκB from translocating to the nucleus. Upon stimulation, IκB is degraded allowing nuclear localization of NFκB where it upregulates pro-inflammatory gene expression [27,28]. The data presented here provide evidence that SLURP1 suppresses the TNF-α-stimulated production of inflammatory cytokines in HCLE cells by stabilizing cytosolic IκB and suppressing the TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB. This effect of SLURP1 appears to be independent of cell type, considering that SLURP1 has a similar effect on NFκB nuclear translocation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells [24]. As neutrophil chemokines IL-8, IL-1β, CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 are direct transcriptional targets of NFκB [27,28], a decrease in their TNF-α-stimulated expression is consistent with a decreased NFκB activity. This effect of SLURP1 in moderating inflammatory cytokine release further establishes the role of SLURP1 as an anti-inflammatory molecule that provides immune privilege to the ocular surface [7,23,24].

To summarize, our findings elucidate the beneficial effects of SLURP1 on HCLE cells in stabilizing the intercellular junctions by promoting the expression of proteins forming the junctional desmosomes, adherens junctions and tight junctions, and suppressing the TNF-α-induced upregulation of inflammatory cytokines by impeding with NF-κB nuclear translocation. Such beneficial effects of SLURP1 may not be limited to corneal epithelial cell types. Considering that these junctional complexes and NFκB-mediated regulation of cytokine production are equally important in other mucosal epithelia such as the skin, colon and lung where SLURP1 is also expressed, we predict that the beneficial effects of SLURP 1 are not only limited to the cornea but also extend to other mucosal epithelia.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

SLURP1 is expressed highly abundantly in the human cornea and is significantly downregulated in human corneal limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells cultured in vitro.

Overexpression of SLURP1 in HCLE cells stabilizes HCLE cell junctions.

Overexpression of SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-8, IL-1b, CXCL1 and CXCL2 in HCLE-SLURP1 cells.

SLURP1 suppresses TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB in HCLE-SLURP1 cells by stabilizing cytosolic IκB.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH Grant R01EY022898 (SKS), NEI Core Grant P30 EY08098, and by unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness and the Eye and Ear Foundation of Pittsburgh. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We are grateful to John Gnalian for technical help, and Kira Lathrop (Imaging Core Facility) for help with imaging.

Abbreviations used

- SLURP1

Secreted Ly-6/uPAR related protein-1

- DSP1

Desmoplakin-1

- DSG1

Desmoglein-1

- TJP1

Tight junction protein-1

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- CXCL

chemokine ligand

- HCLE

human corneal limbal epithelial cell

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB

- TBP

TATA-binding protein

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: S. Swamynathan (Patent); S.K. Swamynathan, (Patent) (Patent number: 9,731,014 Issued in Aug 2017 Titled ‘Use of SLURP1 as an Immunomodulatory Molecule in the Ocular Surface’. Gregory Campbell, None; Anil Tiwari, None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Adermann K, Wattier F, Wattier S, Heine G, Meyer M, Forssmann WG, Nehls M, Structural and phylogenetic characterization of human SLURP-1, the first secreted mammalian member of the Ly-6/uPAR protein superfamily, Protein Sci 8 (1999) 810–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Loughner CL, Bruford EA, McAndrews MS, Delp EE, Swamynathan S, Swamynathan SK, Organization, evolution and functions of the human and mouse Ly6/uPAR family genes, Hum Genomics 10 (2016) 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fischer J, Bouadjar B, Heilig R, Huber M, Lefevre C, Jobard F, Macari F, Bakija-Konsuo A, Ait-Belkacem F, Weissenbach J, Lathrop M, Hohl D, Prud’homme JF, Mutations in the gene encoding SLURP-1 in Mal de Meleda, Hum Mol Genet 10 (2001) 875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Eckl KM, Stevens HP, Lestringant GG, Westenberger-Treumann M, Traupe H, Hinz B, Frossard PM, Stadler R, Leigh IM, Nurnberg P, Reis A, Hennies HC, Mal de Meleda (MDM) caused by mutations in the gene for SLURP-1 in patients from Germany, Turkey, Palestine, and the United Arab Emirates, Hum Genet 112 (2003) 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ward KM, Yerebakan O, Yilmaz E, Celebi JT, Identification of recurrent mutations in the ARS (component B) gene encoding SLURP-1 in two families with mal de Meleda, J Invest Dermatol 120 (2003) 96–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Adeyo O, Allan BB, Barnes RH 2nd, Goulbourne CN, Tatar A, Tu Y, Young LC, Weinstein MM, Tontonoz P, Fong LG, Beigneux AP, Young SG, Palmoplantar keratoderma along with neuromuscular and metabolic phenotypes in Slurp1-deficient mice, J Invest Dermatol 134 (2014) 1589–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Swamynathan S, Swamynathan SK, SLURP-1 modulates corneal homeostasis by serving as a soluble scavenger of urokinase-type plasminogen activator, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55 (2014) 6251–6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lyukmanova EN, Shulepko MA, Kudryavtsev D, Bychkov ML, Kulbatskii DS, Kasheverov IE, Astapova MV, Feofanov AV, Thomsen MS, Mikkelsen JD, Shenkarev ZO, Tsetlin VI, Dolgikh DA, Kirpichnikov MP, Human Secreted Ly-6/uPAR Related Protein-1 (SLURP-1) Is a Selective Allosteric Antagonist of alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor, PLoS One 11 (2016) e0149733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lyukmanova EN, Shulepko MA, Bychkov ML, Shenkarev ZO, Paramonov AS, Chugunov AO, Arseniev AS, Dolgikh DA, Kirpichnikov MP, Human SLURP-1 and SLURP-2 Proteins Acting on Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Reduce Proliferation of Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma HT-29 Cells, Acta Naturae 6 (2014) 60–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Webber RJ, Grando SA, Biological effects of SLURP-1 on human keratinocytes, J Invest Dermatol 125 (2005) 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chimienti F, Hogg RC, Plantard L, Lehmann C, Brakch N, Fischer J, Huber M, Bertrand D, Hohl D, Identification of SLURP-1 as an epidermal neuromodulator explains the clinical phenotype of Mal de Meleda, Hum Mol Genet 12 (2003) 3017–3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Favre B, Plantard L, Aeschbach L, Brakch N, Christen-Zaech S, de Viragh PA, Sergeant A, Huber M, Hohl D, SLURP1 is a late marker of epidermal differentiation and is absent in Mal de Meleda, J Invest Dermatol 127 (2007) 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Horiguchi K, Horiguchi S, Yamashita N, Irie K, Masuda J, Takano-Ohmuro H, Himi T, Miyazawa M, Moriwaki Y, Okuda T, Misawa H, Ozaki H, Kawashima K, Expression of SLURP-1, an endogenous alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric ligand, in murine bronchial epithelial cells, J Neurosci Res 87 (2009) 2740–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Norman B, Davis J, Piatigorsky J, Postnatal gene expression in the normal mouse cornea by SAGE, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45 (2004) 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Swamynathan S, Delp EE, Harvey SA, Loughner CL, Raju L, Swamynathan SK, Corneal Expression of SLURP-1 by Age, Sex, Genetic Strain, and Ocular Surface Health, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56 (2015) 7888–7896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fujii T, Horiguchi K, Sunaga H, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Kasahara T, Tsuji S, Kawashima K, SLURP-1, an endogenous alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric ligand, is expressed in CD205(+) dendritic cells in human tonsils and potentiates lymphocytic cholinergic activity, J Neuroimmunol 267 (2014) 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Matsumoto H, Shibasaki K, Uchigashima M, Koizumi A, Kurachi M, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Kawashima K, Watanabe M, Kishi S, Ishizaki Y, Localization of acetylcholine-related molecules in the retina: implication of the communication from photoreceptor to retinal pigment epithelium, PLoS One 7 (2012) e42841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Moriwaki Y, Watanabe Y, Shinagawa T, Kai M, Miyazawa M, Okuda T, Kawashima K, Yabashi A, Waguri S, Misawa H, Primary sensory neuronal expression of SLURP-1, an endogenous nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligand, Neurosci Res 64 (2009) 403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mastrangeli R, Donini S, Kelton CA, He C, Bressan A, Milazzo F, Ciolli V, Borrelli F, Martelli F, Biffoni M, Serlupi-Crescenzi O, Serani S, Micangeli E, El Tayar N, Vaccaro R, Renda T, Lisciani R, Rossi M, Papoian R, ARS Component B: structural characterization, tissue expression and regulation of the gene and protein (SLURP-1) associated with Mal de Meleda, Eur J Dermatol 13 (2003) 560–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Grando SA, SLURP-1 and −2 in normal, immortalized and malignant oral keratinocytes, Life Sci 80 (2007) 2243–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Grando SA, Overexpression of SLURP-1 and −2 alleviates the tumorigenic action of tobacco-derived nitrosamine on immortalized oral epithelial cells, Biochem Pharmacol 74 (2007) 1315–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Bernard HU, Grando SA, Reciprocal effects of NNK and SLURP-1 on oncogene expression in target epithelial cells, Life Sci 91 (2012) 1122–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Swamynathan S, Buela KA, Kinchington P, Lathrop KL, Misawa H, Hendricks RL, Swamynathan SK, Klf4 regulates the expression of Slurp1, which functions as an immunomodulatory peptide in the mouse cornea, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53 (2012) 8433–8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Swamynathan S, Loughner CL, Swamynathan SK, Inhibition of HUVEC tube formation via suppression of NFkappaB suggests an anti-angiogenic role for SLURP1 in the transparent cornea, Exp Eye Res 164 (2017) 118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Swamynathan S, Tiwari A, Loughner CL, Gnalian J, Alexander N, Jhanji V, Swamynathan SK, The secreted Ly6/uPAR-related protein-1 suppresses neutrophil binding, chemotaxis, and transmigration through human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Sci Rep 9 (2019) 5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Argueso P, Tisdale A, Spurr-Michaud S, Sumiyoshi M, Gipson IK, Mucin characteristics of human corneal-limbal epithelial cells that exclude the rose bengal anionic dye, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47 (2006) 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lan W, Petznick A, Heryati S, Rifada M, Tong L, Nuclear Factor-kappaB: central regulator in ocular surface inflammation and diseases, Ocul Surf 10 (2012) 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lawrence T, The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1 (2009) a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kinoshita S, Adachi W, Sotozono C, Nishida K, Yokoi N, Quantock AJ, Okubo K, Characteristics of the human ocular surface epithelium, Prog Retin Eye Res 20 (2001) 639–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Proksch E, Brandner JM, Jensen JM, The skin: an indispensable barrier, Exp Dermatol 17 (2008) 1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Segre JA, Bauer C, Fuchs E, Klf4 is a transcription factor required for establishing the barrier function of the skin, Nat Genet 22 (1999) 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Swamynathan S, Kenchegowda D, Piatigorsky J, Swamynathan SK, Regulation of Corneal Epithelial Barrier Function by Kruppel-like Transcription Factor 4, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52 (2011) 1762–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Niederkorn JY, Stein-Streilein J, History and physiology of immune privilege, Ocul Immunol Inflamm 18 (2010) 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Azar DT, Corneal angiogenic privilege: angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in corneal avascularity, vasculogenesis, and wound healing (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis), Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 104 (2006) 264–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hazlett LD, Hendricks RL, Reviews for immune privilege in the year 2010: immune privilege and infection, Ocul Immunol Inflamm 18 (2010) 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Barabino S, Chen Y, Chauhan S, Dana R, Ocular surface immunity: homeostatic mechanisms and their disruption in dry eye disease, Prog Retin Eye Res 31 (2012) 271–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Clements JL, Dana R, Inflammatory corneal neovascularization: etiopathogenesis, Semin Ophthalmol 26 (2011) 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gronert K, Resolution, the grail for healthy ocular inflammation, Exp Eye Res 91 (2010) 478–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ambati BK, Nozaki M, Singh N, Takeda A, Jani PD, Suthar T, Albuquerque RJ, Richter E, Sakurai E, Newcomb MT, Kleinman ME, Caldwell RB, Lin Q, Ogura Y, Orecchia A, Samuelson DA, Agnew DW, St Leger J, Green WR, Mahasreshti PJ, Curiel DT, Kwan D, Marsh H, Ikeda S, Leiper LJ, Collinson JM, Bogdanovich S, Khurana TS, Shibuya M, Baldwin ME, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, De Falco S, Witta J, Baffi JZ, Raisler BJ, Ambati J, Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1, Nature 443 (2006) 993–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cursiefen C, Chen L, Saint-Geniez M, Hamrah P, Jin Y, Rashid S, Pytowski B, Persaud K, Wu Y, Streilein JW, Dana R, Nonvascular VEGF receptor 3 expression by corneal epithelium maintains avascularity and vision, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (2006) 11405–11410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].El Annan J, Goyal S, Zhang Q, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Dana R, Regulation of T-cell chemotaxis by programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in dry eye-associated corneal inflammation, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51 (2010) 3418–3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.