Abstract

Currently, over 10 million people worldwide are affected by corneal blindness. Corneal trauma and disease can cause irreversible distortions to the normal structure and physiology of the cornea often leading to corneal transplantation. However, donors are in short supply and risk of rejection is an ever-present concern. Although significant progress has been made in recent years, the wound healing cascade remains complex and not fully understood. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine are currently at the apex of investigation in the pursuit of novel corneal therapeutics. This review uniquely integrates the clinical and cellular aspects of both corneal trauma and disease and provides a comprehensive view of the most recent findings and potential therapeutics aimed at restoring corneal homeostasis.

Keywords: corneal trauma, keratoconus, Fuchs’ dystrophy, diabetic keratopathy, regenerative medicine

1. Introduction

Corneal trauma and disease are highly implicated in contributing to corneal fibrosis, which in turn, can lead to significant vision impairment. Corneal blindness has been reported as second only to cataract in the leading causes of blindness (Whitcher 2001). Although ocular trauma is underreported, injuries contribute significantly to corneal blindness, with 1.5 to 2 million estimated new cases of unilateral blindness (Whitcher 2001). Previous review articles have focused on topics that contribute to corneal disease, including corneal trauma (Willmann and Melanson 2018), corneal burns (Eslani et al. 2014) diabetic keratopathy (Abdelkader et al. 2011), keratoconus (Vazirani and Basu 2013), and Fuchs’ dystrophy (Eghrari et al. 2015a).

In this review, we aimed to compile the current knowledge of both corneal trauma and diseases and provide a comprehensive look at cellular responses and clinical implications of disease and trauma, in different layers of the cornea. Additionally, we discuss current prevention and treatment modalities for corneal trauma and disease, and address potential therapeutic options currently under ongoing investigation.

2. Corneal Anatomy

The cornea is the anterior structure of the eye. Its importance to vision cannot be understated, as it is where light first enters the eye, providing refractive power that aids in focusing light rays on the retina. Corneal thickness varies between individuals based on a variety of factors including age, ethnicity, and body stature. Studies report different values for average corneal thickness, with an average central cornea thickness of around 0.550 mm (Brandt et al. 2001; Galgauskas et al. 2012; Jonuscheit et al. 2017). The human cornea has five distinct layers: epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. In order to maintain a healthy cornea and optimal vision, each layer must function properly.

2.1. Epithelium

The epithelium is the outermost, anterior layer of the cornea, with important functions in immunity, protection, and structural stability of the eye. Corneal epithelium is composed of four to six nonkeratinized, stratified squamous epithelial cell layers, closely connected by tight junctions to prevent entry of fluids and microbes (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Outer epithelial cells are covered by a tear film that helps smooth out minor irregularities present in the epithelial layer, and protect the cornea from pathogens (DelMonte and Kim 2011). Epithelial cells express Toll-like receptors and secrete proinflammatory cytokines alongside Langerhans cells in order to prevent entry of pathogens into the eye. A subbasal nerve plexus within the epithelium gives rise to intraepithelial terminals in the superficial cornea, providing sensory innervation to the cornea (Marfurt et al. 2009). Epithelial cells also function as support cells to the neurons within the epithelium, wrapping around axons similarly to a Schwann cell of the peripheral nervous system (Stepp et al. 2018). With a cell lifespan of seven to ten days, epithelial cells undergo constant replacement via stem cells, which originate from the limbal epithelium at the basal layer (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Basal cells are anchored to basement membrane via hemidesmosomes, a specialized cellular structure that provides stability for the basal epithelium to Bowman’s layer. Nonhealing epithelial defects and corneal erosions are potential pathologies tied to inadequate hemidesmosome connections (DelMonte and Kim 2011). Corneal damage, or trauma, that reaches the basement membrane initiates a process of healing and repair that can last up to six weeks (DelMonte and Kim 2011).

2.2. Bowman’s layer

Posterior to the corneal epithelium lies Bowman’s layer, also known as the anterior limiting membrane. This layer is acellular and notably thin, at approximately 15 micrometers thickness that decreases in thickness over time (DelMonte and Kim 2011). Collagen IV is the most prevalent protein, followed by laminin. The organization of these proteins is critical for the overall corneal transparency. (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Bowman’s layer is an attachment site of collagen lamellae from the corneal stroma that lies beneath (Morishige et al. 2006). Nerve fibers from the stroma give penetrate through Bowman’s layer as they travel anteriorly to the epithelium, with greater density in the peripheral cornea (Marfurt et al. 2009). Critically, corneal damage that affects Bowman’s layer (seen in traumatic injury or herpes simplex keratitis) can result in scarring, with very limited regenerative capacity (DelMonte and Kim 2011).

2.3. Stroma

The corneal stroma is the thickest layer of the human cornea, accounting for nearly 90% of the overall thickness (Meek and Knupp 2015). The major cell type of the stroma, the keratocyte, produces proteins that provide structure to the stroma, including collagen, matrix metalloproteinases, and glycosaminoglycans (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Corneal stroma is organized in a framework such that light scattering is prevented. Disturbing the stroma, which may occur in various types of corneal injury/disease, disturbs transparency of the cornea and significantly affects visual acuity. A class of water-soluble proteins known as crystallins are known for their role in preventing distortion of light and therefore vision (Jester 2008). Examples of crystallins include aldehyde dehydrogenase class 3, transketolase, and alpha-enolase. While relatively quiescent after early development, keratocytes can become activated in response to injury and differentiate into myofibroblasts, mediating a cascade of cellular responses discussed later in this review (Moller-Pedersen 2004). Dendritic cells and macrophages, also housed by the corneal stroma, play a role in immunity and inflammation (Hassell and Birk 2010). Stromal nerve bundles from the trigeminal nerve enter the cornea at the corneoscleral limbus, from which they comprise a subepithelial plexus of neurons that go on to penetrate Bowman’s layer (Marfurt et al. 2009).

2.4. Descemet’s Membrane

Descemet’s membrane, also called the posterior limiting membrane, is an acellular layer that lies posterior to the corneal stroma. This is a thin layer (approximately 10 nanometers in the average adult) and is established by the underlying endothelial cells. The anterior portion of Descemet’s membrane is present in utero and consists of banded collagen lamellae, while the posterior portion consists of non-banded collagen which increases in thickness over time (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Descemet’s membrane is composed of collagen type IV and VII (Eghrari et al. 2015b). This layer is key to the relative dehydration of the cornea. Breaks in Descemet’s membrane, can lead to acute corneal edema and vision impairments (DelMonte and Kim 2011).

2.5. Endothelium

The posterior layer of the cornea is a monolayer of simple squamous epithelium. The corneal endothelial layer is crucial to maintain appropriate concentrations of ions in the stroma, as well as providing nourishment to the corneal stroma and epithelium (Van den Bogerd et al. 2018). Na+/K+ and bicarbonate dependent Mg2+ ATPases are the main transporters involved with maintaining a dehydrated corneal stroma (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Aquaporin-1 expression and intracellular carbonic anhydrase also aid in this role (DelMonte and Kim 2011). The endothelial layer is also a barrier to fluid entry from the anterior chamber, with tight junctions in between endothelial cells (Eghrari et al. 2015b). Loss of proper endothelium function results in corneal hydrops and swelling. Endothelial cells have limited ability to regenerate in response to injury, as remaining cells migrate and stretch to fill the deficit left by injury. While there are a few hypotheses as to why the endothelial cells are relatively senescent, insufficient production and binding of growth factors along with oxidative stress appear to be major contributors (Araki-Sasaki et al. 1997; Joyce et al. 2009). Maintaining transparency requires an endothelial cell density of 400–500 cells/mm2, which can be problematic in the setting of significant corneal injury (Joyce 2012).

3. Corneal Reaction to Injury and Disease

The cornea can be afflicted by disease or injury in several ways. While injury to the cornea and the diseased cornea differ in their origins of dysfunction, the integration of both aspects provides insight to the differences and similarities involved. This review will discuss three different types of corneal injuries and three types of common disease. These were selected based on their overall prevalence and their impact on the different cellular layers of the human cornea. This section describes the clinical and cellular aspects of some of those conditions that can ultimately result in corneal fibrosis and possibly vision loss. Table 1 summarizes the etiology, prevention, and treatment of the injuries and diseases discussed in this review.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical aspects of selected corneal injuries and disease

| Disease | Etiology | Primary layer affected | Prevention | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laceration/Perforation | Trauma | Varies (Epithelium to Endothelium) | Eye Protection | Surgical repair of the injury |

| Foreign Bodies | Trauma | Varies (Epithelium to Endothelium) | Shatter-proof eye protection | Removal of foreign body and surgical repair |

| Chemical Burns | Acidic or Alkali Agents | Varies (Epithelium to Endothelium) | Splash protective eyewear, eye washing stations | Irrigation |

| Diabetic Keratopathy | Type I Diabetes: Autoimmune Type II Diabetes: Multifactorial | Epithelium and Bowman’s Layer | Blood glucose control | No treatment; Symptomatic management |

| Keratoconus | Multifactorial | Stroma | Not preventable; avoid UV exposure and rubbing eyes | Lenses, Collagen Crosslinking, Keratoplasty |

| Fuchs’ Dystrophy | Genetic | Endothelium | Not preventable | Dehydration, DSEK/DMEK |

3.1. Clinical aspects of injury and disease

3.1.1. Lacerations and perforations

Corneal lacerations and perforations often occur from similar injuries, and can be differentiated by the depth of injury. Corneal lacerations involve the stroma, while the injury penetrates the endothelium in corneal perforations (Vinuthinee et al. 2015). Corneal lacerations are painful injuries often caused by high-speed, flying objects that disrupt the epithelial layer. When complex lacerations occur, the corneal collagen lamella can shred, which makes it difficult to close the wound properly (Soeken et al. 2018). Perforations to the cornea can be caused by foreign objects, microbial keratitis, and immune disorders (Choudhary and Agrawal 2018). Corneal perforation can lead to a host of complications to the eye, including hyphema, microhyphema, misshapen iris, shallow anterior chamber, and decreased visual acuity (Willmann and Melanson 2018). Closure and repair of the wound is critical in order to reduce the risk of infection and to preserve the clear, smooth surface of the cornea necessary for optimal visual acuity and avoid scarring, as seen in Figure 1. Failure to close the wound properly can result in complications such as endopthalmitis, epithelial ingrowth, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and tissue death. In both laceration and perforation, inflammation can occur which can be sterile or secondary to infection and must be followed closely (Ahmed et al. 2015; Ratzlaff et al. 2017; Choudhary and Agrawal 2018). Corneal lacerations and perforations, like other corneal injuries, require timely management in order to preserve the anatomical integrity of the cornea (Choudhary and Agrawal 2018). A severe corneal laceration affecting the eyelids and resulting in an open globe is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Corneal scarring after corneal laceration. Rigid gas-permeable contact lens has been fitted to improve vision.

Figure 2.

Severe laceration of eyelids and globe after an assault.

3.1.2. Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies can become lodged with various depth in the cornea and can go initially undetected without a high degree of suspicion. This can be aided by slit-lamp examination, as shown in Figure 3. Corneal foreign bodies often present similarly to laceration or perforation, causing pain, tearing, and blepharospasm (Willmann and Melanson 2018). These similar presentations make it possible for small foreign bodies to go initially unnoticed, causing potential for further damage to the eye. If the foreign body becomes lodged under the upper eyelid, repeated trauma can occur from blinking, resulting in numerous linear abrasions to the cornea (Willmann and Melanson 2018). Epithelial defects resulting from foreign body impregnations tend to heal quickly and can be tolerated without any pathological reaction to the cornea (Qin et al. 2018). However, these injuries often fail to heal if any fragments of the foreign body are left behind. This is often seen with metallic foreign bodies due to the accumulation of rust that forms around the metal (Willmann and Melanson 2018). Fungal and bacterial infections are a major risk depending on the foreign body involved, as fungal or bacterial pathogens may be introduced to the cornea (Ahmed et al. 2015). The resulting inflammation or infection can be severe and can potentially lead to endophthalmitis (Ono et al. 2018). Surgical removal of the foreign body is sometimes needed, but the removal of deep fragments may result in significant scarring which can distort the topography of the cornea and disrupt normal vision (Qin et al. 2018).

Figure 3.

Corneal foreign body.

3.1.3. Burns

Chemical burns to the cornea are an ocular emergency that can devastate the cornea. Corneal burns are usually very painful and carry a high risk of blindness, even with treatment (Zhou et al. 2017). Chemical burns are caused, mainly, by acidic or alkaline agents. Alkali burns are often more severe than burns caused by acid due to the lipophilic nature of alkali agents, which allow for deeper penetration into the cornea (Dua et al. 2001). Acid burns tend to cause less damage to the cornea than alkali burns as many corneal proteins bind to the acid and act as a chemical buffer (Ramponi 2017). The most common agents implicated in alkali burns include ammonium hydroxide (used in the production of fertilizer), sodium hydroxide (a cleaning agent), and calcium hydroxide (found in lime plaster and cement) (Ramponi 2017). The most common acid burns reported are caused by sulphuric acid from car batteries and bleaches, and hydrochloric acid from swimming pools (Dua et al. 2001; Singh et al. 2013). Burns can also result in damage to the limbus, carrying a high risk of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). LCSD is characterized by chronic epithelial defects and inflammation that can lead to corneal opacity and poor visual outcomes (Gupta et al. 2018; Utheim et al. 2018). Corneal burns can carry a poor prognosis depending on the severity. Aside from severe pain and discomfort, complications from burns include permanent scarring, dry-eye, vascularization, chemosis of the conjunctiva, infection, visual impairment, and permanent vision loss (Basu et al. 2018; Willmann and Melanson 2018). Scarring that occurs after the initial burn, mediated by the immune response, are a major long term complication that can necessitate corneal transplant in severe cases (Willmann and Melanson, 2018).

3.1.4. Diabetic Keratopathy

Corneal defects are a major clinical concern, afflicting not only those suffering from corneal trauma, but also those with diabetes mellitus (DM). DM can cause abnormal changes to the ocular surface which have been termed diabetic keratopathy (DK) (Sayin et al. 2015). Both type 1 and type 2 DM are known to cause DK, as both conditions have chronic hyperglycemia as a hallmark feature (Misra et al. 2016; Bikbova et al. 2018). DK commonly refers to reduced corneal sensitivity, nerve fiber density, and disrupted/delayed epithelial wound healing (Bikbova et al. 2016). These changes to the normal corneal epithelial structure and physiology can result in a host of conditions related to the cornea, including epithelial defects (shown in Figure 4), weakened epithelial barrier, secondary scarring, edema, infections, loss of sensitivity, dry eye, neurotrophic keratitis, and ultimately vision loss (Sayin et al. 2015; Ljubimov 2017). The prolonged hyperglycemia that accompanies DM has long been known to result in delayed wound healing, and this problem extends to the cornea as well. Corneal injuries and defects often persist for a substantially longer duration than they otherwise would in healthy individuals due to changes in the epithelium described later in the review (Bikbova et al. 2016).

Figure 4.

Corneal epithelial defect in patient with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

3.1.5. Keratoconus

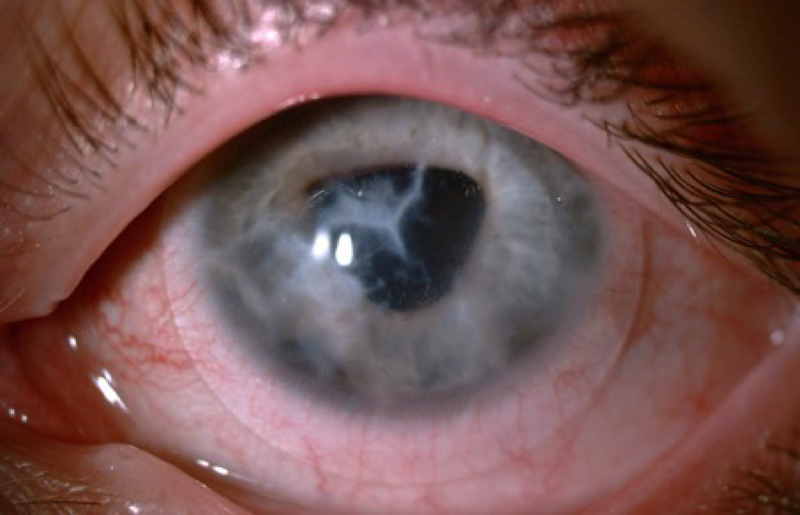

Keratoconus (KC) is a progressive ectatic disease of the cornea (Khaled et al. 2017). Clinically, the central or paracentral corneal stroma undergoes gradual thinning and loss of structural integrity that leads to bulging of the cornea, giving it a cone-shaped appearance (pictured in Figure 5) (Soiberman et al. 2017). KC is associated with poor visual outcomes due to progressive myopia, irregular astigmatism, and corneal thinning (Vazirani and Basu 2013; Mukhtar and Ambati 2018). KC usually has an onset in the second decade of life, initially involving one eye with the other eye involved later in about half of patients (Gordon-Shaag et al. 2015; Li et al. 2004).

Figure 5.

Cone shaped cornea seen in keratoconus.

All corneal layers show histopathological structural changes in KC (Khaled et al. 2017). Studies have shown that basal epithelial cells in KC patients displayed enlargement, irregular arrangement, and a significant reduction in cell density when compared to healthy individuals (Ghosh et al. 2017). Other studies demonstrated either no significant change of corneal epithelium (Erie et al. 2002) or thickened corneal epithelium in KC patients (Hollingsworth et al. 2005; Weed et al. 2007; Bitirgen et al. 2015). In addition, increased visibility of cornea nerve fibers on slit lamp examination can occur in KC (Barr et al. 1999; Sherwin and Brookes 2004). Breaks in Descemet’s membrane can result in acute corneal edema known as corneal hydrops, resulting in blurring of vision due to edema (Fan Gaskin et al. 2014). In several studies, the endothelial layer does not exhibit any changes during KC progression (Weed et al. 2007; Sandali et al. 2013; El-Agha et al. 2014). However, some studies have shown an increase in endothelial cell density in KC (Lema and Duran 2005), while others have reported significant decrease in severe stages of the disease (Ucakhan et al. 2006; Mocan et al. 2008). Finally, studies have shown ruptures within Bowman’s layer and the coexistence of a proliferative collagenous tissue derived from the stroma beneath Bowman’s layer (Sykakis et al. 2012). However, it remains unknown whether Bowman’s layer contributes to the pathogenesis of KC. Overall the pathobiology of KC remains elusive.

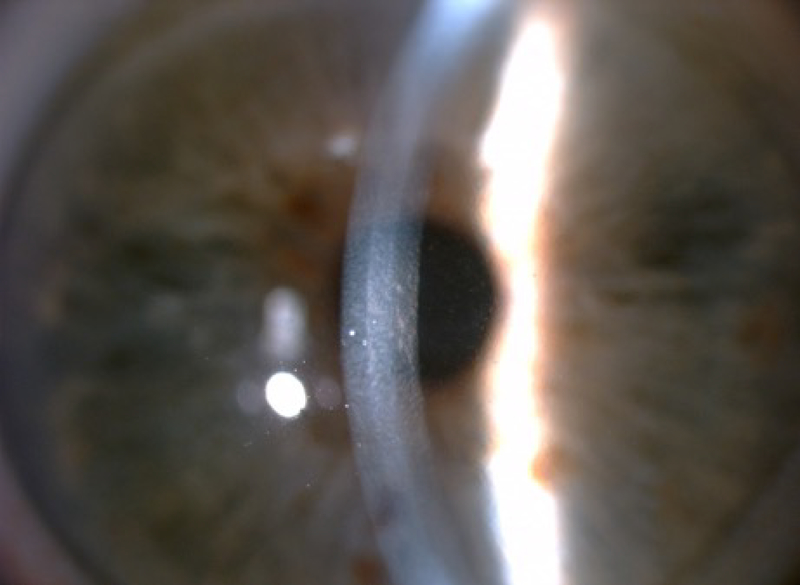

3.1.6. Fuchs’ Dystrophy

Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is a progressive hereditary disease that is characterized by dysfunction of the corneal endothelium (Eghrari et al. 2015a). FECD can be classified into two types: early-onset, which affects a person from early childhood and progresses into their 30s, and late-onset, which generally presents in the fourth or fifth decade (Eghrari et al. 2015a). Fuchs’ is believed to affect 4% of the American population over the age of 40 (Elhalis et al. 2010). When the corneal endothelium cannot properly regulate fluid absorption of the cornea, edema can spread through to the stroma and cause hazy vision. Progressive loss of endothelium results in other structural manifestations, including increased stromal and Descemet’s membrane thickness, worsening stromal and epithelial edema, and, in severe cases, epithelial bullae (Eghrari et al. 2015a). A patient suffering from FECD can experience blurred vision in the mornings that clears up throughout the day, with worsening and prolonged symptoms as the disease progresses (Eghrari et al. 2015a). The most indicative FECD clinical manifestation is the formation of excrescences called “guttae” on the Descemet’s membrane, which can be observed by slit-lamp examination, as shown in Figure 6. Guttae initially appear in the medial cornea and migrate peripherally over time (Eghrari et al. 2015a). The number of guttae and size of the regions with guttae present have been used in clinical diagnosis to stage Fuchs’ dystrophy progression (Gottsch et al. 2006).

Figure 6.

Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy on slit-lamp examination with guttata.

3.2. Cellular responses to injury and disease

3.2.1. Lacerations/perforations, foreign bodies, and burns

Injury to the cornea results in a cascade of events involved in wound healing. The wound healing mechanisms involved in the three cellular layers of the cornea display similarities and differences. The epithelium, stroma, and endothelium exhibit cell responses in reaction to a number of mechanisms including cell proliferation, migration, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and growth factor/cytokine mediation (Ljubimov and Saghizadeh 2015; Sharma et al. 2015; Saghizadeh et al. 2017). Complexity of the wound healing process is compounded by the distinct manner in which each cell type reacts to various injuries.

Epithelial cells undergo regular stem cell regeneration and migration from the limbus. These limbal stem cells (LSCs) differentiate in the limbus and migrate to the center of the cornea as a “sheet” to close the wound (Sejpal et al. 2013). When LSCs are damaged and/or lost, fibrosis can occur. In response to injury, corneal epithelial cells and immune cells secrete a host of cytokines and growth factors that mediate cell migration and adhesion to the site of injury (Karamichos et al. 2014, Ljubimov and Saghizadeh 2015, Menko et al. 2019). In a process that is not fully understood, cytokines, growth factors, and alterations in the basement injury that occur after injury cause LSCs to increase their replication, especially in response to large wounds (Ljubimov and Saghizadeh 2015). After reepithelialization, epithelial cells restore the basement membrane (Menko et al. 2019).

Under normal physiological conditions and when corneal injury is restricted only to the epithelium, the healing process is generally rapid and resolves completely (Ross and Deschenes 2017). The role of hyaluronan in LSC differentiation and function investigated in the context of ECM composition (Gesteira et al. 2017). Hyaluronan (HA) is an ECM component that is naturally synthesized by a class of integral membrane proteins known as hyaluronan synthases (HASs). This study demonstrated that the LSC niche was composed of a specialized HA matrix that differed from those present in the rest of the corneal epithelium. The disruption of the specific HA matrix within the LSC niche leads to compromised corneal epithelial regeneration, suggesting a major role of HA in maintaining the LSC phenotype.

Recently, a group demonstrated the role of β-cellulin (BC) in corneal wound healing (Jeong et al. 2018). BC is an EGF family member that induces extracellular-signal-related kinase (ERK) and Akt pathway signaling. This study found that BC stimulated the phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 pathway, triggering recovery from corneal wounds in mice and also that inhibiting ERK1/2 phosphorylation delayed recovery, suggesting that BC could serve as a potential treatment in corneal epithelial wound healing.

Wound healing that involves the corneal stroma is more complex. When damage extends deeper than the epithelium, stromal keratocytes undergo apoptosis caused by epithelial interleukin-1 (IL-1) (Kaur et al. 2009; Barbosa et al. 2010; Saghizadeh et al. 2017). The keratocytes transform into myofibroblasts that have reduced corneal crystallins, which contributes to corneal opacity. Myofibroblasts proliferate and migrate toward the wound and produce ECM proteins, including collagens I, III, IV, and V, fibronectin and tenascin-C, and disrupt the normal corneal ECM organization (Tandon et al. 2010; Chaurasia et al. 2015). Expression of the fibrotic marker alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) is a key feature of myofibroblasts that augments their contractile activity. The mechano-transduction system enables tractive force to be exerted, spreading the α-SMA positive fibers across the ECM, resulting in tissue distortion and fibrosis (Zhang et al. 1994; Wynn and Ramalingam 2012; Shu and Lovicu 2017). Simultaneously, ECM signals are transduced into intracellular signaling and α-SMA is regulated in part by activated transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), along with growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and specialized ECM proteins, such as fibronectin.

Fibrosis in the cornea can restrict the capacity for clear vision after recovery from injury. To address this problem, many studies have focused on suppressing and reversing corneal fibrosis. Suppression of fibroblast proliferation and inhibition of corneal fibrosis has been demonstrated via decorin, bone morphogenic protein 7, Smad7, pirfenidone, mitomycin C, trichostatin A, and vorinostat (Sharma et al. 2009; Mohan et al. 2011; Tandon et al. 2013; Kim and Keating 2015; Sharma et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2017; Anumanthan et al. 2018). TGF-β has been shown to either induce fibrosis further via TGF-β1 or to ameliorate fibrosis via TGF-β3 (Karamichos et al. 2014; Guo et al. 2016). Activation of TGF-βRI initiates downstream signaling pathways including Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways. Epithelial mesenchymal transitions (EMT) has been tied to both through Smad signaling and non-Smad signaling via Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK), ERK1 and ERK2 (Lebrun 2012; Darby et al. 2014; Karamichos, et al. 2014; Shu and Lovicu 2017). Intermediate-conductance calmodulin/calcium-activated K+ channels 3.1 (KCa3.1) plays a role in corneal wound healing and fibrosis, recently reported by Anumanthan et al. 2018. Their study demonstrated that blocking KCa3.1 channels with TRAM-34 leads to decreased expression of pro-fibrotic factors mediated by TGFβ1. KCa3.1 proteins are activated in response to injury; their expression is found in the mitochondria and cytoplasmic membranes and are known to regulate cell cycle progression and proliferation. KCa3.1 channels seem to increase cellular proliferation by increasing intracellular Ca2+ signaling, altering cell cycle progression (Anumanthan et al. 2018). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells derived from adult bone marrow that provide a beneficial source of cells for tissue repair and regeneration following injury. A recent study investigated the effects of MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM) on corneal stromal cells with the use of a rabbit in vitro model, detecting wound healing mediators, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), PDGF, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), TGFβ1, interleukin 8 (IL8), and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) (Jiang et al. 2017). This study demonstrated that MSC-CM increased wound closure rate, enhanced cell survival, and promoted corneal epithelial wound healing, providing additional insight on recovery from corneal injury.

When corneal injuries or dystrophies affect the endothelium of the cornea, the consequences can be severe. Corneal endothelial cells (CECs) are different from epithelial cells and keratocytes in that they form a monolayer which are mitotically arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. They respond to injury via cell migration and spreading, closing the wound gap without replication (Saghizadeh et al. 2017; Shu and Lovicu 2017). When CECs are damaged or lost, the endothelial barrier can fail and cause the cornea to swell from an influx of fluid. The discovery of corneal endothelial stem cells could be highly beneficial in treating injured/lost endothelial cells. A review by Joko et al. 2017 concluded that promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) expression in cultured CECs was closely related to the formation of cell-cell contact. Additionally, TGFβ2 suppressed proliferation of cultured human CECs while promoting their migration through p38 MAPK activation (Joko et al. 2017). Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) pathway, a signal cascade involved in sensing cell tension, has been implicated in endothelial migration, adhesion, and proliferation. It has been demonstrated that ROCK inhibition enhances wound healing in the presence of Decemet’s membrane (Bhogal et al. 2017). Another study investigated whether injection of CECs supplemented with ROCK inhibitor into the anterior chamber would increase CEC density. They found that CEC density was increased after 24 weeks in 11 patients with bullous keratopathy (Kinoshita et al. 2018). Progress has been achieved in producing CECs in an in vitro two-step process. Chen et al. 2015 demonstrated that mouse Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) induced and expressed CEC differentiation markers after being subjected to the two-step process of cell differentiation. Their findings offer potentially promising development for endothelial replacements associated with CEC dysfunction and wound-related complications (Chen et al. 2015; Saghizadeh et al. 2017).

3.2.2. Diabetic Keratopathy

As described above, DK results from the prolonged hyperglycemia that can cause severe morphological changes to the healthy corneal structure. DK leads to a host of abnormalities in the cornea, including thickening of Bowman’s layer, abnormal adhesion between the stroma and basement membrane, weak attachment between basal epithelial cells and the basement membrane, epithelial fragility, accumulation of sorbitol, decreased oxygen consumption and uptake, increased polyol metabolism, altered epithelial hemidesmosomes, and increased glycosyltransferase activity (Sayin et al. 2015; Ljubimov 2017).

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are toxic compounds deposited in the basement membrane of corneal epithelium that have been partially implicated in the development of DK. AGEs alter the structure and functions of ECM, basement membranes, and blood vessel walls (Kaji 2005; Bejarano and Taylor 2019). Kaji et al. (2000) investigated the laminin of the corneal epithelial basement membrane and found that increased levels of AGEs in 8 human diabetic corneas led to weakened attachment between basal cells and the basement membrane. Calvo-Maroto et al. (2016) reported that AGE accumulation in the basement membrane and stroma of DM corneas were responsible for clinically observed increases in auto-fluorescence. AGEs correspond to their respective receptors (RAGEs) which trigger intracellular signaling with NF-κB activation and formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Kim et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2013; Ljubimov 2017). A recent study investigated eyes of mice with RAGE+/+ and RAGE−/− and observed increased RAGE fluorescent staining and mRNA expression in wounded corneas and concluded that eyes of RAGE−/− mice had slower re-epithelialization than eyes with RAGE+/− and RAGE+/+ genotypes (Nass et al. 2017). Bao et al. (2017) investigated the effected of DM on the biomechanical behavior of the cornea in 20 alloxan-induced rabbits. After 8 weeks, the authors found that corneas of diabetic mice showed significant increases in mechanical stiffness via increases in corneal thickness and tangent modulus with higher blood glucose levels.

DM patients are more susceptible to trauma due to decreased corneal sensitivity. This is believed to be caused by neuronal changes resulting from axonal degeneration of corneal unmyelinated nerves that occurs due to the chronic hyperglycemia (Bikbova et al. 2018). These neuronal changes can cause delayed epithelial wound healing, as corneal nerves release epitheliotropic subtances that are essential in maintaining the integrity of the cornea (Sayin et al. 2015; Bikbova et al. 2016). Recently, Pham et al. (2017) investigated the effects of a combination of the known neuroprotective molecule, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in an in vivo mouse injury model. The study found that atglistatin, a PEDF-R inhibitor, blocked changes to the cornea and trigeminal ganglia (TG), suggesting an active cornea-TG axis driven by PEDF-R activation that fosters axon outgrowth in the cornea. Another recent study demonstrated the application of fibronectin-derived peptide PHSRN on the corneal epithelium facilitated corneal epithelial wound healing in diabetic rats (Morishige et al. 2017). The authors had previously shown that the combination of substance P-derived peptide FGLM-amide and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) promoted corneal epithelial wound closure in diabetic rats. The PHSRN sequence is known to function as a second cell-binding site of fibronectin in addition to arginine, glycine, and aspartic acid sequence of the protein that interacts with integrin α5β1 expressed at the cell surface. The PHSRN peptide was shown to facilitate corneal epithelial migration both in vivo and in vitro (Morishige et al. 2017). A recent study found that encoding soluble epoxide hydrolase (EPHX2) played an important role in contributing to diabetic corneal complications and that EPHX2−/− mice showed enhanced sensory innervation and regeneration in diabetic corneas 1 month after debridement (Sun et al. 2018). These findings suggest that targeting EPHX2 pharmacologically may present new therapies for patients with DK.

3.2.3. Keratoconus

Cellular, protein, genetic, and hormonal variations have been found to be associated with KC (Gordon-Shaag et al. 2015; Sharif et al. 2018). Many studies hypothesize that the trigger for KC lies in the epithelium, where the corneal epithelial basement membrane was reported to be irregular or in some severe cases, absent (Torricelli et al. 2013). An abnormal architecture of the interface between the basal cell layer of the epithelium and the underlying stroma was revealed in KC corneas (Khaled et al. 2017). Reduced collagen XII staining was seen at the level of the epithelial basement membrane in KC corneas, a finding that was later confirmed in a proteomic study of KC (Chaerkady et al. 2013). Collagen type XII is noted to attach the epithelial layer to the underlying stroma (Shetty et al. 2019). These observations on the epithelial-stromal interface, in KCs, do not exclusively explain the classic corneal bulging or stromal thinning seen in these patients.

Overall, KC pathology maybe attributed to abnormal tissue response to various unidentified stimuli, leading to keratocyte depletion, loss of collagen, and eventually result in a biomechanically weak cornea (Naderan et al. 2017). Studies have reported altered matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression in KC. MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13 have been shown to be elevated in tears of KC patients (Khaled et al. 2017). Proteinase inhibitors, on the other hand, which mainly include α1-protease inhibitor, α2-macroglobulin, and tissue inhibitors of MMP, were downregulated in KC (Benjamin and Khalil 2012).

Involvement of various genes has also been reported in KC, including, but not limited to, SOD1 (superoxide dismutase 1), VSX1 (visual system homeobox 1), and DOCK9 (dedicator of cytokinesis 9); genes coding for collagens COL4A3 (type IV collagen alpha3) and COL4A4 (type IV collagen alpha4) have also been studied as potential genes involved in KC pathogenesis (Bykhovskaya et al. 2016; Rong et al. 2017). Recent notable developments in the field of KC genetics is the recognition of polymorphisms in the LOX (lysyl oxidase) gene (Zhang et al. 2015). Studies have reported that changes in LOX distribution and its decreased activity might be potential reasons for the insufficient collagen cross-linking in KC, which is a hallmark of this disease (Dudakova et al. 2012). Moreover, Abo-Amero et al., reported that a mutation in the micro-RNA (miRNA) gene MIR184 (OMIM 613146) was considered to play a role in KC (2015). MIR184 is highly expressed in the cornea, and a mutation in the seed region of MIR184 could substantially affect its function (Hughes et al. 2011). These studies imply the involvement of multiple genes in the pathogenesis of KC, and suggest the importance of deciphering their genetic code in contributing to our knowledge of KC pathogenesis (Gordon-Shaag et al. 2015).

In addition, sex hormones have profound effects on the eye (Bajwa et al. 2012). Androgen and estrogen receptors have been identified in both anterior and posterior segments of the human eye (Gupta et al. 2005). Studies have suggested that KC could be a systemic disease driven by altered hormones leading to corneal stromal thinning. Sex hormone levels in saliva samples from KC patients have detected significantly increased dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) levels and reduced estrone levels in these patients compared to healthy controls (McKay et al. 2016). A recent study reported similar alterations in DHEA, estrone, and estriol in tears, serum, and saliva samples from 147 KC patients when compared to healthy controls (Sharif et al. 2019). These results suggest that altered hormone levels may contribute to stromal thinning in the KC cornea.

3.2.4. Fuchs’ Dystrophy

Despite significant efforts, the etiology of Fuchs’ Dystrophy remains unclear. Signaling mechanisms and pathways, as well as genetic associations have been proposed. FECD has been shown to affect several signaling pathways, including those related to oxidative stress, inflammation, and ECM production (Cui et al. 2018).

Analysis of human corneas with FECD has shown raised levels of AGEs, down-regulation of antioxidants (SOD2, MT3, and TXNDR1,), and decreased levels of peroxiredoxins, all known to be associated with oxidative stress (Nita and Grzybowski 2016). High activity of TGF-β has also been reported, a theorized cause of the elevated production of ECM proteins which result in higher occurrence of unfolded protein response (Okumura et al. 2015). Gene expression analysis of endothelium, post-keratoplasty, revealed altered expression of EMT genes, elevated expression of inflammatory genes, increased ROS activity, and increased production of ECM genes (Cui et al. 2018). Apoptosis occurs in the endothelium, as the disease progresses, which leads to the decreased barrier function that is a hallmark of the FECD (Elhalis et al. 2010). However, Li et al. showed with in-situ end labeling that high levels of apoptotic cells are present not only in the endothelium but in all cell layers of the FECD cornea. Immunohistochemistry of the diseased corneas revealed elevated levels of apoptotic markers such as Fas, FasL, Bcl-2, and Bax. Increased levels of the proteins Clusterin and transforming growth factor-B-induced protein (TGFBIp) has been reported to have a relationship with the increased thickness of the Descemet’s membrane in FECD corneas (Okumura et al. 2017).

Genetic analysis has revealed four loci that exhibit linkage to Fuchs’: FCD1 (13pTel-13q12.13), FCD2 (18q21.2–18q21.32), FCD3 (5q33.1–5q35.2), and FCD4 (9p22.1–9p24.1) (Eghrari et al. 2015a). FCD1 and FCD3 were discovered from analysis of a large single family of Caucasian descent and a large single family of unspecified descent, respectively (Elhalis et al. 2010). A multi-family study consisting of three separate large families revealed FCD2 (Elhalis et al. 2010). FCD4 is the only locus that has been found to interact with another pathological allele, transcription factor-8 (TCF8) (Eghrari et al. 2015a). Other loci not having reached the LOD (logarithm of the odds) threshold of linkage in analysis but that have been found to possibly be involved in the FECD phenotype have been located on chromosomes 1 (rs760594), 7 (rs257376), 10 (rs1889974), 15 (rs352476 and rs235512), and 17 (rs938350) (Eghrari et al. 2015a). Coding mutations have been identified for many genes, including TCF8, which encodes ZEB1, LOXHD1, and AGBL1, a gene involved in posttranslational modification and identified in a single-family study (Eghrari et al. 2015a; Vedana et al. 2016). Mutations in the gene COL8A2 have been found in patients affected by early-onset FECD, on those of Korean descent (Mok et al. 2009). Three missense mutations for SLC4A11, a bicarbonate transporter, have been identified in a set of unrelated patients of Chinese and Indian descent (Eghrari et al. 2015a). Recent large genome-wide association studies have concluded that transcription factor-4 (TCF4) could also be a causative gene in the pathophysiology of FECD, specifically through trinucleotide expansion of the CTG repeat (Nakano et al. 2015; Okumura et al. 2015).

4. Targets and treatment options

4.1. Management of Corneal Injury

Treatment for traumatic injury to the cornea requires rapid, but accurate, triage of the injury to appropriately plan intervention. This begins with obtaining a complete history of the incident and a comprehensive eye examination, preferably with fluorescein dye (Ahmed et al. 2015). Flourescein stains the basement membrane beneath the corneal epithelium as well as cells undergoing apoptosis (Bandamwar et al.2014). Flourescein dye is also useful in assessing for perforation as the clinician assesses for leakage of fluid from the injured area, known as the Seidel test. Due to the extremely painful nature of corneal trauma, a topical anesthetic may be necessary to allow for examination (Ahmed et al. 2015).

4.1.1. Perforations and Lacerations

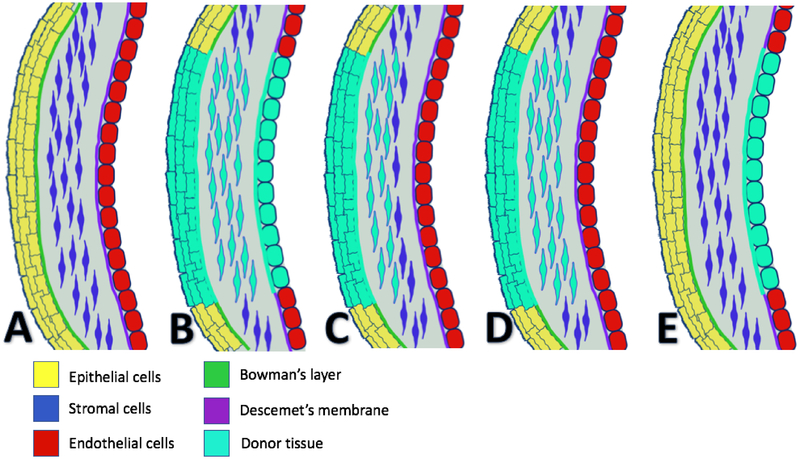

Treatment of corneal injuries differs based upon the severity of the injury. In cases of perforation or laceration, water-tight closure of the cornea at the site of injury is necessary. This can be accomplished with either suture or adhesives, such as cyanoacrylate glue (Ratzlaff et al. 2017). This is an ophthalmologic emergency, and immediate repair is necessary to prevent further damage to the cornea and loss of vision altogether (Choudhary and Agrawal 2018). Application of a pressure patch, a soft pad placed over the closed eyelids and taped down firmly, was once recommended in addition to closure of the injury. This has fallen out of favor, as it does not improve pain and may delay healing of the injury (Lim et al. 2016). Topical antibiotics are necessary to prevent bacterial superinfection. While there are many appropriate choices, it is important to select an antibiotic with coverage for Psuedomonas aeruginosa in contact lens wearers, who are often colonized (Wipperman and Dorsch 2013). If the wound is highly suspicious for infection, which often depends on the object that caused the injury, a culture of the wound may be performed (Vinuthinee et al. 2015). Close follow up is recommended after initial treatment to monitor for complications such as corneal ulcers, bacterial keratitis, or recurrent erosions, and patients should be advised to return to their physician if their symptoms worsen (Brissette et al. 2014). In very severe or complicated cases where initial measures fail, closure of the laceration or perforation is not enough and keratoplasty may need to be performed at a later date to restore vision. Figure 7 is a graphical depiction of different types of keratoplasty used to treat corneal diseases.

Figure 7.

Examples of different corneal transplant procedures. Normal cornea shown in A with epithelium (yellow), Bowman’s layer (green), stroma (blue), Descemet’s membrane (purple), and endothelium (red). Not drawn to scale. Transplanted cornea is indicated by light blue, with types of keratoplasty as follows: Penetrating keratoplasty (B), Superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty (C), Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (D), and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) (E).

4.1.2. Foreign Bodies

Foreign bodies present a few unique challenges in addition to those caused by a corneal trauma without foreign body. Management mentioned above, including closure of the wound and prophylaxis against infection and other complications, still applies. If a foreign body is present in the cornea, there is a higher risk of bacterial keratitis, which may be especially true in certain foreign bodies, such as objects exposed to dirt or water (Vinuthinee et al. 2015). Metallic objects can result in formation of rust in the cornea, especially if the object is present for a prolonged period of time (Ozkurt et al. 2014). Rust can cause corneal scarring with decreased visual acuity. Presence of a foreign body should be suspected in almost all cases of corneal trauma, and may be found by inverting the inner surface of the eyelid (Wipperman and Dorsch 2013). In many cases, this technique allows for removal of the foreign body with a cotton swab. X-ray, ultrasound, and CT are all appropriate imaging modalities when the diagnosis is unclear, and should be followed by the removal of the foreign object and closure of the wound. Prevention with proper eye protection during the most common activities associated with intraocular foreign bodies (chiseling, hammering, grass trimming) is critical to avoid devastating injury to the eye (Serinken et al. 2013). Additionally, supervision and education to ensure proper use of safety equipment is necessary, as one study found that a safety device was in use in 34.2% of corneal foreign body injuries (Gerente et al. 2008).

4.1.3. Chemical Burns

Chemical burns to the cornea can cause irreversible damage, if not handled quickly. The cornerstone of treatment is extensive and prolonged irrigation the eye, preferably within 1–2 minutes (Chau et al. 2010). A delay of even 20 seconds can lead to worse outcomes due to greater magnitude of pH change within the cornea (Rihawi et al. 2006). 30–60 minutes of irrigation is usually recommended, although 15 minutes may be preferred with some buffering solutions together with adequate volume of irrigation (Rihawi et al. 2007). Continuous irrigation causes both dilution of the chemical agent responsible for the burn and reversal of the abnormal pH. Different irrigation fluids have been studied including water, saline, Ringers lactate, and various other buffers- of note, tap water is effective and often readily available (Rihawi et al. 2006). Amphoteric or buffering solutions may be more effective at neutralizing pH after a burn. Borate buffer solution has been shown to reverse pH more rapidly and has FDA approval (Scott et al. 2015). In any case, selection of a buffer should not delay irrigation with a different solution. Additionally, specialized devices to improve irrigation, such as a Morgan lens, can be used in a health care setting (Ramponi 2017). After the acute treatment of the burn, continued monitoring for complications as they arise is imperative. Topical corticosteroids, citrate, and preservative-free tear solutions can be used to promote a healing environment after a chemical burn (Eslani et al. 2014). Ascorbic acid has long been recommended to reduce the risk of corneal ulceration and perforation after a burn (Levinson et al. 1976). With all of the corneal injuries described above, prevention with appropriate eyewear is imperative, especially in high risk populations (construction, chemical engineers, and certain sports or hobbies, to name a few).

4.2. Diabetic Keratopathy

Early diagnosis of DM is imperative, as corneal manifestations occur early in the disease process (Papanas and Ziegler 2013). AGEs mediate the disease, making glucose control important in prevention (Kaji 2005). Maintaining normoglycemia through lifestyle changes and the wide range of available pharmaceutical options is imperative to reducing corneal complications of diabetes. There is some evidence that normoglycemia improves the ability of the cornea to heal (Abdelkader et al. 2011). Glucose control modalities differ between type I and type 2 diabetics, with insulin replacement as the backbone of type 1 diabetes treatment and many existing options for type 2 diabetes, including insulin. Monitoring for keratopathy during regular diabetic examinations is recommended (Gao et al. 2015).

DK-related complications should be treated quickly and aggressively as diabetic patients are at an increased risk. Certain growth factors, such as insulin and nerve growth factor, show some promise in compensating for delayed corneal healing seen in DK (Abdelkader et al. 2011). Aldose-reductase inhibitors, which block an enzyme in the pathway that converts glucose to sorbitol, resulting in osmotic damage to the cornea, have also been used with some effectiveness (Abdelkader et al. 2011). Additionally, as diabetes affects tear synthesis and effectiveness of the tear film, treatment of dry eye with available modalities (lubricants, eye drops, punctate plugs, etc.) may be needed (Gao et al. 2015). Warm compresses (a part of “eyelid hygiene”) are a low risk therapy often recommended for patients with dry eye (Zhang et al. 2017). Recurrent corneal erosions may be treated with epithelial debridement if associated with basement membrane dystrophy (Vo et al. 2015). Nevertheless, current therapies offer only symptomatic treatment without addressing the underlying disease.

4.3. Keratoconus

Keratoconus, when suspected, can be diagnosed with the aid of corneal topography, indicated by abnormal curvature of the cornea (Belin et al. 2014). This progressive disease can be managed early in its course with spectacles and contact lenses to correct vision, though these do not delay KC progression (Brown et al. 2014). Collagen cross-linking (CXL) has been shown to halt changes of KC. CXL involves application of riboflavin eye drops to the cornea, followed by ultraviolet light, resulting in covalent bond formation between collagen proteins that strengthens the cornea (Brown et al. 2014). Reported clinical outcomes include improved visual acuity and subjective visual function and slowing changes in maximum keratometry, a measurement of the steepest part of the cornea used as a parameter to assess progression of the disease (Hersh et al. 2017). As with all therapies, there are side effects, the most common of which is corneal haze. Fortunately, this is usually transient and may be part of the healing process (Hersh et al. 2017).

Traditional CXL involves removing the epithelium before application of riboflavin and UV light. However, recent evidence suggests that a transepithelial approach, which does not remove the epithelium, may provide similar results with decreased risk of complications, with various methods currently being attempted to maximize riboflavin penetration (Wen et al. 2018). It remains to be seen if transepithelial CXL will provide long term stability of the cornea to the extent that standard epithelium-off CXL does. There remains some question regarding how long traditional CXL is effective, as it has been FDA approved in the US since April 2016 and in Europe for over a decade. More studies with long term follow-up are necessary to show long term efficacy and complications that may occur years after the procedure (Brown et al. 2014). Penetrating keratoplasty is also used to treat KC, as the abnormal cornea is replaced with donor cornea, but this is not a first-line treatment due to graft rejection, need for immunosuppression, glaucoma risks, and other surgical complications.

4.4. Fuchs’ Dystrophy

Management of FECD often begins with conservative management that can be escalated as required. As the disorder results in corneal edema, medical management to dehydrate the cornea can provide some benefit, such as hypertonic saline eye drops (Sarnicola et al. 2019). In patients with mild edema that fluctuates throughout the day, having multiple pairs of spectacles to use throughout the day may provide relief (Sarnicola et al. 2019). While these treatments are not curative, they may delay the need for a transplant, perhaps indefinitely. In more severe cases, surgical operations are required. Various surgical techniques can be used to correct vision in FECD. Penetrating keratoplasty replaces the central cornea with a donor cornea, and can take up to 24 months for full visual recovery (Claesson et al. 2002). While this is an option, penetrating keratoplasty for Fuchs’ dystrophy has fallen out of favor, with surgical procedures that replace only the posterior cornea taking its place (Deng et al. 2018). One such technique is Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK), which attaches donor endothelium, Descemet’s membrane, and a thin layer of stroma to the posterior stroma of the host (Bruinsma et al. 2013). This is believed to carry a lower risk of graft rejection compared to penetrating keratoplasty, as there is less tissue transplanted and it lies more posteriorly in a more immune privileged area (Nanavaty et al. 2014). Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) differs from DSEK in that only the donor endothelium and Descemet’s membrane are transplanted (Deng et al. 2018). A recent meta-analysis compared DMEK and DSEK, which showed DMEK to have more favorable outcomes in regards to visual acuity (Marques et al. 2018). Even so, no keratoplasty is without the risk of graft rejection or detachment (Koizumi et al. 2013). There is some question of how much donor tissue must be transplanted in order to correct edema (if any) and if removal of Descemet’s membrane and guttae is sufficient to allow host endothelial stem cells to correct the defect (Bruinsma et al. 2013). Another therapy that has shown some promise is Rho kinase inhibitors, which alters molecular pathways involved in cell replication, migration, and apoptosis (Koizumi et al. 2013). Rho kinase inhibitors may stimulate proliferation of endothelial cells, perhaps providing a treatment without the need for donor tissue.

5. Corneal Bioengineering and Stem Cells

All of the pathologies discussed in this review can potentially be treated with corneal transplantation, which may be warranted in severe cases. Yet, these procedures involve risk, long term follow-ups, and require donor corneas, which are in short supply. A global survey covering 91% of the world’s population found that 12.7 million people were waiting for a donor cornea (Gain et al. 2016). The high demand for donor tissue has created demand for solutions that do not require donor tissue. Current keratoprostheses, such as the Boston type-1 Kpro or osteo-odonto Kpro, can be used, but carry long term and serious complications, including glaucoma, inflammatory conditions, and endophthalmitis (Avadhanam et al. 2015). Longevity and optimal visual acuity are also concerns. Tissue engineering and stem cell treatments may be able to alleviate some of the need for donor corneas, if current research is any indication.

5.1. Corneal tissue engineering

Corneal bioengineering typically involves use of a scaffold, either a decellularized cornea or biomaterial, on which epithelial, stromal, and endothelial cells can be embedded. Using corneal cells, as opposed to a keratoprosthetic, allows better potential for corneal function to be maintained (Chen et al. 2018). Many biomaterials are currently being researched, including collagen, silk fibroin, gelatin, chitosan, and synthetic polymers; of these, collagen is the most used (Chen et al. 2018). Still, difficulty remains in engineering a tissue that has the optical transparency, mechanical properties, and topography of donor cornea (de Araujo and Gomes 2015). Challenges that must be addressed specific to the corneal stroma are achieving proper orientation of the lamellar sheets and maintaining functioning keratocytes (Chen et al. 2018). Innervation and regeneration of the tissue are two problems that are most often overlooked, which will limit longevity of the grafted tissue unless they are addressed (Ghezzi et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2018). This may be addressed with further optimization of use of cells within the engineered tissue, as functioning cells can meet the demand for repair and regeneration of the grafted tissue. Even so, an acellular, biosynthetic implant has safely been used in humans as an alternative to anterior lamellar keratoplasty in a small group of patients (Fagerholm et al. 2010; Islam et al. 2018). This implant did support nerve regeneration and allowed for sensation to corneal touch. Continuing to address these limitations will require more research and innovation, but could provide a solution for the shortage of donor corneas.

5.2. Stem cells

The use of stem cells to treat corneal disease is in varying stages in the three cell types of the cornea. Limbal epithelial stem cell transplants have been performed for decades, most often for limbal stem cell deficiency from chemical burns to the cornea (Saghizadeh et al. 2017; Fernandez-Buenaga et al. 2018). In unilateral conditions, grafted tissue from the unaffected eye can be used. In bilateral conditions, grafted tissue may be allogeneic (from donor cornea) or autologous (from cultivated oral mucosa). Multiple surgical techniques for limbal stem cell transplant are currently in use (Yin and Jurkunas 2017, Fernandez-Buenaga et al. 2018). Generation of limbal epithelium from embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells has not yet been optimized to the point of use in clinical practice and is currently limited by reproducibility, risk of tumorigenesis, and cost (Saghizadeh et al. 2017).

The corneal stroma contains mesenchymal stem cells below the limbus that have been isolated and differentiated into multiple cell types, including corneal keratocytes (Du et al. 2005, Funderburgh et al. 2016, Saghizadeh et al. 2017). Use of autologous stem cells may be able to be used to treat corneal blindness in diseases that affect the stroma, with diminished risk of rejection. Limbal biopsy-derived stromal stem cells from humans have been shown to decrease neovascularization and scarring after corneal injury in mice (Basu et al. 2014). Stromal stem cells have also been used to increase flap adherence after a laser in-situ keratomileusis-like flap was created in sheep corneas, without compromising corneal transparency (Morgan et al. 2016). Additionally, these cells have been used in treatment of corneal opacity in a lumican-null mouse model, resulting in correction of corneal thickness and with restored transparency (Du et al 2009). This suggests that stromal stem cells can remodel the extracellular matrix of the stroma (Funderburgh et al. 2016). Corneal stromal stem cells also have potential in bioengineering, potentially seeded on acellular scaffolding as described above (Funderburgh et al. 2016).

As discussed above, it is currently believed that there are no endothelial stem cells present in the human cornea. Due to this, stem cells may have potential use in treating endothelial dystrophies, such as Fuchs’ dystrophy. Corneal endothelium can be generated from human pluripotent stem cells by first inducing ocular neural crest stem cells by promoting WNT signaling, then suppressing TGF- β and ROCK to produce corneal endothelial cells (Zhao and Afshari 2016). Cultured human embryonic stem cells have been implanted onto damaged Descemet’s membrane in vitro, with the grafted cells taking on a polygonal shape similar to the hexagonal shape seen naturally (Hanson et al. 2017). The authors admit that their system requires more optimization to ensure that all of the cells have endothelial properties. Even so, these discoveries show promise in the use of stem cells to generate endothelium to replace the current need for donor tissue when performing endothelial keratoplasty.

6. Conclusions

Corneal injuries and the diseases discussed carry a significant burden of ocular disease. Fortunately, recent research has given more insight into the molecular mechanisms at work within the cornea. In some cases, such as limbal epithelial stem cell transplant in corneal burns and rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibition in FECD, research into biochemistry has given potential therapeutics. More information is especially needed in diseases where the pathogenesis remains unclear, such as in keratoconus. In reviewing the current and potential therapies for corneal injury and disease, there is a trend toward treatments becoming less invasive and more targeted towards the diseased portion of cornea. Overall, this has resulted in better visual outcomes and less complications for patients. Yet, in some cases, such as diabetic keratopathy, no effective treatment exists. Continued research and clinical attention to these problems, as well as pushing the limitations of stem cells and tissue engineering, will hopefully provide better solutions in the years to come.

Highlights.

Cornea trauma and disease can cause irreversible vision distortions.

Clinical and molecular aspects of cornea trauma and disease are discussed.

Recent findings and therapeutic options are outlined.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute for their continuous support. Images were obtained from the Aarhus University Hospital with appropriate permission to publish.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [EY028888]

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdelkader H, Patel DV, McGhee CNj, and Alany RG 2011. ‘New therapeutic approaches in the treatment of diabetic keratopathy: a review’, Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 39: 259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Amero KK, Helwa I, Al-Muammar A, Strickland S, Hauser MA, Allingham RR, and Liu Y 2015. ‘Screening of the Seed Region of MIR184 in Keratoconus Patients from Saudi Arabia’, Biomed Res Int, 2015: 604508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed F, House RJ, and Feldman BH 2015. ‘Corneal Abrasions and Corneal Foreign Bodies’, Prim Care, 42: 363–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anumanthan G, Gupta S, Fink MK, Hesemann NP, Bowles DK, McDaniel LM, Muhammad M, and Mohan RR 2018. ‘KCa3.1 ion channel: A novel therapeutic target for corneal fibrosis’, PLoS One, 13: e0192145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki-Sasaki K, Danjo S, Kawaguchi S, Hosohata J, and Tano Y 1997. ‘Human hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in the aqueous humor’, Jpn J Ophthalmol, 41: 409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avadhanam VS, Smith HE, and Liu C 2015. ‘Keratoprostheses for corneal blindness: a review of contemporary devices’, Clin Ophthalmol, 9: 697–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa SK, Singh S, and Bajwa SJ 2012. ‘Ocular tissue responses to sex hormones’, Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 16: 488–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandamwar KL, Papas EB, and Garrett Q 2014. ‘Fluorescein staining and physiological state of corneal epithelial cells’, Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 37: 213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao F, Deng M, Zheng X, Li L, Zhao Y, Cao S, Yu A, Wang Q, Huang J, and Elsheikh A 2017. ‘Effects of diabetes mellitus on biomechanical properties of the rabbit cornea’, Exp Eye Res, 161: 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa FL, Chaurasia SS, Kaur H, de Medeiros FW, Agrawal V, and Wilson SE 2010. ‘Stromal interleukin-1 expression in the cornea after haze-associated injury’, Exp Eye Res, 91: 456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr JT, Schechtman KB, Fink BA, Pierce GE, Pensyl CD, Zadnik K, and Gordon MO 1999. ‘Corneal scarring in the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study: baseline prevalence and repeatability of detection’, Cornea, 18: 34–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Hertsenberg AJ, Funderburgh ML, Burrow MK, Mann MM, Du Y, Lathrop KL, Syed-Picard FN, Adams SM, Birk DE, and Funderburgh JL 2014. ‘Human limbal biopsyderived stromal stem cells prevent corneal scarring’, Sci Transl Med, 6: 266ra172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Mohan S, Bhalekar S, Singh V, and Sangwan V 2018. ‘Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) in failed cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation (CLET) for unilateral chronic ocular burns’, Br J Ophthalmol, 102: 1640–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano E, and Taylor A 2019. ‘Too sweet: Problems of protein glycation in the eye’, Exp Eye Res, 178: 255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin MW, Villavicencio OF, and Ambrosio RR Jr. 2014. ‘Tomographic parameters for the detection of keratoconus: suggestions for screening and treatment parameters’, Eye Contact Lens, 40: 326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin MM, and Khalil RA 2012. ‘Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as investigative tools in the pathogenesis and management of vascular disease’, Exp Suppl, 103: 209–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogal M, Lwin CN, Seah XY, Peh G, and Mehta JS 2017. ‘Allogeneic Descemet’s Membrane Transplantation Enhances Corneal Endothelial Monolayer Formation and Restores Functional Integrity Following Descemet’s Stripping’, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 58: 4249–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikbova G, Oshitari T, Baba T, Bikbov M, and Yamamoto S 2018. ‘Diabetic corneal neuropathy: clinical perspectives’, Clin Ophthalmol, 12: 981–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikbova G, Oshitari T, Baba T, and Yamamoto S 2016. ‘Neuronal Changes in the Diabetic Cornea: Perspectives for Neuroprotection’, Biomed Res Int, 2016: 5140823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitirgen G, Ozkagnici A, Bozkurt B, and Malik RA 2015. ‘In vivo corneal confocal microscopic analysis in patients with keratoconus’, Int J Ophthalmol, 8: 534–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt JD, Beiser JA, Kass MA, and Gordon MO 2001. ‘Central corneal thickness in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS)’, Ophthalmology, 108: 1779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette A, Mednick Z, and Baxter S 2014. ‘Evaluating the need for close follow-up after removal of a noncomplicated corneal foreign body’, Cornea, 33: 1193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SE, Simmasalam R, Antonova N, Gadaria N, and Asbell PA 2014. ‘Progression in keratoconus and the effect of corneal cross-linking on progression’, Eye Contact Lens, 40: 331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma M, Tong CM, and Melles GR 2013. ‘What does the future hold for the treatment of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy; will ‘keratoplasty’ still be a valid procedure?’, Eye (Lond), 27: 1115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaya Y, Margines B, and Rabinowitz YS 2016. ‘Genetics in Keratoconus: where are we?’, Eye Vis (Lond), 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Maroto AM, Perez-Cambrodi RJ, Garcia-Lazaro S, Ferrer-Blasco T, and Cervino A 2016. ‘Ocular autofluorescence in diabetes mellitus. A review’, J Diabetes, 8: 619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaerkady R, Shao H, Scott SG, Pandey A, Jun AS, and Chakravarti S 2013. ‘The keratoconus corneal proteome: loss of epithelial integrity and stromal degeneration’, J Proteomics, 87: 122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau JP, Lee DT, and Lo SH 2010. ‘Eye irrigation for patients with ocular chemical burns: a systematic review’, JBI Libr Syst Rev, 8: 470–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasia SS, Lim RR, Lakshminarayanan R, and Mohan RR 2015. ‘Nanomedicine approaches for corneal diseases’, J Funct Biomater, 6: 277–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Chen JZ, Shao CY, Li CY, Zhang YD, Lu WJ, Fu Y, Gu P, and Fan X 2015. ‘Treatment with retinoic acid and lens epithelial cell-conditioned medium in vitro directed the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells towards corneal endothelial cell-like cells’, Exp Ther Med, 9: 351–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, You J, Liu X, Cooper S, Hodge C, Sutton G, Crook JM, and Wallace GG 2018. ‘Biomaterials for corneal bioengineering’, Biomed Mater, 13: 032002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary DS, and Agrawal N 2018. ‘New Surgical Modality for Management of Corneal Perforation Using Bowman Membrane’, Cornea, 37: 919–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson M, Armitage WJ, Fagerholm P, and Stenevi U 2002. ‘Visual outcome in corneal grafts: a preliminary analysis of the Swedish Corneal Transplant Register’, Br J Ophthalmol, 86: 174–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Zeng Q, Guo Y, Liu S, Wang P, Xie M, and Chen J 2018. ‘Pathological molecular mechanism of symptomatic late-onset Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy by bioinformatic analysis’, PLoS One, 13: e0197750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby IA, Laverdet B, Bonte F, and Desmouliere A 2014. ‘Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing’, Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 7: 301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo AL, and Gomes JA 2015. ‘Corneal stem cells and tissue engineering: Current advances and future perspectives’, World J Stem Cells, 7: 806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelMonte DW, and Kim T 2011. ‘Anatomy and physiology of the cornea’, J Cataract Refract Surg, 37: 588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng SX, Lee WB, Hammersmith KM, Kuo AN, Li JY, Shen JF, Weikert MP, and Shtein RM 2018. ‘Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Safety and Outcomes: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology’, Ophthalmology, 125: 295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua HS, King AJ, and Joseph A 2001. ‘A new classification of ocular surface burns’, Br J Ophthalmol, 85: 1379–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, SundarRaj N, and Funderburgh JL 2005. ‘Multipotent stem cells in human corneal stroma’, Stem Cells, 23: 1266–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Carlson EC, Funderburgh ML, Birk DE, Pearlman E, Guo N, Kao WW, and Funderburgh JL 2009. ‘Stem cell therapy restores transparency to defective murine corneas’, Stem Cells, 27: 1635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudakova L, Liskova P, Trojek T, Palos M, Kalasova S, and Jirsova K 2012. ‘Changes in lysyl oxidase (LOX) distribution and its decreased activity in keratoconus corneas’, Exp Eye Res, 104: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eghrari AO, Riazuddin SA, and Gottsch JD 2015. ‘Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy’, Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 134: 79–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eghrari AO, Riazuddin SA, and Gottsch JD 2015. ‘Overview of the Cornea: Structure, Function, and Development’, Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 134: 7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agha MS, El Sayed YM, Harhara RM, and Essam HM 2014. ‘Correlation of corneal endothelial changes with different stages of keratoconus’, Cornea, 33: 707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhalis H, Azizi B, and Jurkunas UV 2010. ‘Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy’, Ocul Surf, 8: 173–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erie JC, Patel SV, McLaren JW, Nau CB, Hodge DO, and Bourne WM 2002. ‘Keratocyte density in keratoconus. A confocal microscopy study(a)’, Am J Ophthalmol, 134: 689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslani M, Baradaran-Rafii A, Movahedan A, and Djalilian AR 2014. ‘The ocular surface chemical burns’, J Ophthalmol, 2014: 196827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm P, Lagali NS, Merrett K, Jackson WB, Munger R, Liu Y, Polarek JW, Soderqvist M, and Griffith M 2010. ‘A biosynthetic alternative to human donor tissue for inducing corneal regeneration: 24-month follow-up of a phase 1 clinical study’, Sci Transl Med, 2: 46ra61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Gaskin JC, Patel DV, and McGhee CN 2014. ‘Acute corneal hydrops in keratoconus - new perspectives’, Am J Ophthalmol, 157: 921–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Buenaga R, Aiello F, Zaher SS, Grixti A, and Ahmad S 2018. ‘Twenty years of limbal epithelial therapy: an update on managing limbal stem cell deficiency’, BMJ Open Ophthalmol, 3: e000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, and Du Y 2016. ‘Stem Cells in the Limbal Stroma’, Ocul Surf, 14: 113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, and Thuret G 2016. ‘Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking’, JAMA Ophthalmol, 134: 167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galgauskas S, Krasauskaite D, Pajaujis M, Juodkaite G, and Asoklis RS 2012. ‘Central corneal thickness and corneal endothelial characteristics in healthy, cataract, and glaucoma patients’, Clin Ophthalmol, 6: 1195–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Zhang Y, Ru YS, Wang XW, Yang JZ, Li CH, Wang HX, Li XR, and Li B 2015. ‘Ocular surface changes in type II diabetic patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy’, Int J Ophthalmol, 8: 358–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerente VM, Melo GB, Regatieri CV, Alvarenga LS, and Martins EN 2008. ‘[Occupational trauma due to superficial corneal foreign body]’, Arq Bras Oftalmol, 71: 149–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesteira TF, Sun M, Coulson-Thomas YM, Yamaguchi Y, Yeh LK, Hascall V, and CoulsonThomas VJ 2017. ‘Hyaluronan Rich Microenvironment in the Limbal Stem Cell Niche Regulates Limbal Stem Cell Differentiation’, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 58: 4407–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi CE, Rnjak-Kovacina J, and Kaplan DL 2015. ‘Corneal tissue engineering: recent advances and future perspectives’, Tissue Eng Part B Rev, 21: 278–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Mutalib HA, Kaur S, Ghoshal R, and Retnasabapathy S 2017. ‘Corneal Cell Morphology in Keratoconus: A Confocal Microscopic Observation’, Malays J Med Sci, 24: 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Shaag A, Millodot M, Shneor E, and Liu Y 2015. ‘The genetic and environmental factors for keratoconus’, Biomed Res Int, 2015: 795738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottsch JD, Sundin OH, Rencs EV, Emmert DG, Stark WJ, Cheng CJ, and Schmidt GW 2006. ‘Analysis and documentation of progression of Fuchs corneal dystrophy with retroillumination photography’, Cornea, 25: 485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Hutcheon AE, and Zieske JD 2016. ‘Molecular insights on the effect of TGF-beta1/-beta3 in human corneal fibroblasts’, Exp Eye Res, 146: 233–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Joshi J, Farooqui JH, and Mathur U 2018. ‘Results of simple limbal epithelial transplantation in unilateral ocular surface burn’, Indian J Ophthalmol, 66: 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PD, Johar K Sr., Nagpal K, and Vasavada AR 2005. ‘Sex hormone receptors in the human eye’, Surv Ophthalmol, 50: 274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Rodier JT, Sharma A, Giuliano EA, Sinha PR, Hesemann NP, Ghosh A, and Mohan RR 2017. ‘Targeted AAV5-Smad7 gene therapy inhibits corneal scarring in vivo’, PLoS One, 12: e0172928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson C, Arnarsson A, Hardarson T, Lindgard A, Daneshvarnaeini M, Ellerstrom C, Bruun A, and Stenevi U 2017. ‘Transplanting embryonic stem cells onto damaged human corneal endothelium’, World J Stem Cells, 9: 127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell JR, and Birk DE 2010. ‘The molecular basis of corneal transparency’, Exp Eye Res, 91: 326–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh PS, Stulting RD, Muller D, Durrie DS, Rajpal RK, and Group United States Crosslinking Study 2017. ‘United States Multicenter Clinical Trial of Corneal Collagen Crosslinking for Keratoconus Treatment’, Ophthalmology, 124: 1259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth JG, Efron N, and Tullo AB 2005. ‘In vivo corneal confocal microscopy in keratoconus’, Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 25: 254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AE, Bradley DT, Campbell M, Lechner J, Dash DP, Simpson DA, and Willoughby CE 2011. ‘Mutation altering the miR-184 seed region causes familial keratoconus with cataract’, Am J Hum Genet, 89: 628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Buznyk O, Reddy JC, Pasyechnikova N, Alarcon EI, Hayes S, Lewis P, Fagerholm P, He C, Iakymenko S, Liu W, Meek KM, Sangwan VS, and Griffith M 2018. ‘Biomaterials-enabled cornea regeneration in patients at high risk for rejection of donor tissue transplantation’, NPJ Regen Med, 3: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong WY, Yoo HY, and Kim CW 2018. ‘beta-cellulin promotes the proliferation of corneal epithelial stem cells through the phosphorylation of erk1/2’, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 496: 359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV 2008. ‘Corneal crystallins and the development of cellular transparency’, Semin Cell Dev Biol, 19: 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]