Abstract

Background:

Although single or multiple sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on the prefrontal cortex over a few weeks improved cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), effects of repeated tDCS over longer period and underlying neural correlates remain to be elucidated.

Objective:

This study investigated changes in cognitive performances and regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (rCMRglc) after administration of prefrontal tDCS over 6 months in early AD patients.

Methods:

Patients with early AD were randomized to receive either active (n = 11) or sham tDCS (n = 7) over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) at home every day for 6 months (anode F3/cathode F4, 2 mA for 30 minutes). All patients underwent neuropsychological tests and brain 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans at baseline and 6-month follow-up. Changes in cognitive performances and rCMRglc were compared between the two groups.

Results:

Compared to sham tDCS, active tDCS improved global cognition measured with Mini-Mental State Examination (p for interaction = 0.02) and language function assessed by Boston Naming Test (p for interaction = 0.04), but not delayed recall performance. In addition, active tDCS prevented decreases in executive function at a marginal level (p for interaction < 0.10). rCMRglc in the left middle/inferior temporal gyrus was preserved in the active group, but decreased in the sham group (p for interaction < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Daily tDCS over the DLPFC for 6 months may improve or stabilize cognition and rCMRglc in AD patients, suggesting the therapeutic potential of repeated at-home tDCS.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Transcranial direct current stimulation, Cognition, Positron emission tomography, Regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent type of dementia, affecting 5.5 million individuals over age 65 in the US alone [1]. Although AD is primarily characterized by progressive loss of memory, other cognitive domains such as language, visuospatial skills, and executive functions are also frequently impaired [2]. Despite its increasing prevalence and debilitating impact of AD, current treatment strategies demonstrate limited efficacy in preventing, slowing, or stopping the progression of the disease. Therefore, the exploration and development of novel treatments for AD are of highest importance.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that delivers a weak electrical current to the brain through scalp electrodes. Previous research has indicated that tDCS can modulate cerebral cortical function by inducing changes in cortical excitability [3]. Compared to other brain stimulation methods such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), tDCS is relatively safe, simple, portable, and inexpensive to administer [4].

An increasing number of studies have reported cognitive enhancing effects of tDCS in both healthy individuals and patients with cognitive impairment. While some studies targeted the temporal lobe [5–7], several other studies targeted the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) since it has widespread connections to cortical and subcortical regions and is involved in various cognitive functions including executive control and memory [8]. In particular, the left DLPFC may play crucial roles in self-initiation of memory strategy use and consolidation of information for the formation of long-term memory trace [9, 10]. In healthy individuals, tDCS over the left DLPFC have shown to improve long-term memory, working memory, verbal fluency, and planning ability [11–14]. In patients with AD, recognition memory was enhanced by a single session (2mA for 30 minutes) of tDCS in the left DLPFC [15]. Multiple tDCS sessions of the left DLPFC were also tried in AD patients and global cognition was improved after 10 daily sessions (2mA for 25 minutes) [16]. A case report suggested that global cognitive function of a mild AD patient remained stable over 3 months after 10 daily sessions of tDCS over the left DLPFC (2mA for 20 minutes) combined with cognitive training [17]. However, effects of multiple tDCS sessions over longer period are needed to be further investigated, although a case study reported that 8 months of daily tDCS in the temporal lobe (2mA for 30 minutes) improved memory and stabilized cognitive decline in an early-onset AD patient [18]. Recently, it has been suggested that home-based tDCS may be effective for repeated administrations over long periods [19].

Neuroimaging studies in early-stage AD have indicated structural and functional deficits mainly in the temporal and parietal regions [20]. However, neural correlates underlying the effects of tDCS in AD remain to be investigated. Our previous 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) study in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) showed that 9 sessions of tDCS in the DLPFC over 3 weeks (2mA for 30 minutes) improve subjective memory functioning and regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (rCMRglc) in multiple brain areas such as the prefrontal, anterior cingulate, insular, hippocampal, and parahippocampal regions [21]. These results suggest that effects of tDCS may not be limited to the target site, but spread to other brain areas.

This study aimed to examine effects of home-based daily sessions of tDCS in the DLPFC over 6 months on cognitive function and rCMRglc in patients with early-stage AD, using neuropsychological tests and brain FDG-PET. We used bi-hemispheric stimulation (anode F3/cathode F4) based on our previous study in MCI [21] and following considerations. Bilateral prefrontal resources are often recruited for some cognitive processes such as working memory [22] and inhibitory effects of cathodal stimulation on cognition are weak or nonexistent [23]. In addition, bilateral stimulation may deliver current more deeply and broadly due to interhemispheric interactions and therefore may have wider effects on brain networks [24, 25].

Methods

Participants

Patients between the ages of 60 and 85 years with early-stage probable AD were recruited at the Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital (Incheon, South Korea) during the period from July to September 2017. The diagnosis of early-stage probable AD was made if the patient had a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0.5 or 1, and met the diagnostic criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV [26] and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria [27]. Participants were excluded from the study if they had contraindications to tDCS (e.g., metallic implants in the head or history of seizure), history of head trauma, epilepsy, stroke, mixed or vascular dementia, or other neurological or psychiatric disorders. All patients had not received tDCS before enrollment and were being treated with donepezil at a dosage of 5 mg/day during the study period. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Since no prior study examined effects of tDCS over several months in AD, sample size calculation was based on a previous study, whereby MMSE was improved after 10 daily sessions of tDCS over the left DLPFC in patients with AD [16]. At 2-month follow-up, the estimated effect size was 1.33 (Cohen’s d). With an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.8, the sample size was calculated as 10 patients for each group. Assuming both potentially larger effect sizes and follow-up loss over the longer stimulation period in this study, we aimed to recruit 10 patients per group.

Study protocol

This study used a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled design consisting of active or sham tDCS treatment. Participants visited the hospital on at least seven different days including one baseline visit, three hospital-based tDCS sessions, two regular check-up visits (2-month post-stimulation & 4-month post-stimulation), and one 6-month post-stimulation follow-up visit. After enrollment, a research nurse who was not involved in the evaluation and analysis randomly assigned the patients into active or sham tDCS group using a computer program and set the tDCS devices to active or sham stimulation mode. The first three tDCS sessions were completed at the hospital under the supervision of the research nurse. At the first session, the research nurse provided the training and made sure a family caregiver could independently set up and use the tDCS device at home. Participants underwent cognitive assessment and brain FDG-PET imaging before the first stimulation (baseline) and after the end of the treatment period (6-month post-stimulation follow-up).

Transcranial direct current stimulation

Active or sham tDCS was applied via two surface electrodes with saline-soaked sponges (6 cm in diameter) every day for 6 months using the YDS-301N device (YBrain Inc, South Korea). The anodal electrode was placed over the left DLPFC (F3; 10 – 20 EEG system) and the cathodal electrode over the right DLPFC (F4). For the active condition, the current was ramped up to 2.0 mA (current density, 0.07 mA/cm2) over 30 seconds, remained at 2.0 mA for 29 minutes, and ramped down to 0 mA over 30 seconds. For the sham condition, the current was ramped up to 2 mA over 30 seconds and ramped down over next 30 seconds. The devices were set to be used only once a day and the usage logs were automatically stored after each session. We checked the logs after the patients returned the devices at the follow-up visits.

Neuropsychological assessment

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [28] and neuropsychological test battery were administered at baseline and 6-month follow-up. The latter consists of subtests that assess multiple cognitive domains including attention (Digit Span Test: forward and backward), language (Boston Naming Test [BNT]; repetition), visuospatial function (Rey Complex Figure Test [RCFT]: copy; Clock Drawing Test), memory (Seoul Verbal Learning Test [SVLT]: immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition; RCFT: immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition), and executive function (Contrasting Program; Go-no go Test; Controlled Oral Word Association Test [COWAT]: animal, supermarket, and Korean letters; Stroop Test: word reading, and color reading) (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, we administered the CDR [29] and CDR-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SOB). Neuropsychological testing was conducted by a licensed neuropsychologist.

Image acquisition and analysis

Brain FDG-PET scans were performed using a Discovery PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) at baseline and 6-month follow-up. After intravenous injection of 185 to 259 MBq of FDG, participants rested in a supine position with eyes closed in a quiet, dimly lit room for 40 minutes. Forty-seven transaxial images were acquired with a matrix of 128 × 128 and a slice thickness of 3.27 mm (pixel size = 1.95 × 1.95 mm2) using 3D acquisition mode. Sixteen slices of CT images were also obtained for attenuation correction. The total scan time was 15 minutes. Standard filtering and ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm were applied for the reconstruction of PET images.

PET images were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK). All images were spatially normalized to the SPM PET template (Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada), resliced with a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3, and smoothed with an 8 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel. Then, the images were scaled to the mean uptake of the pons [30] using proportional scaling, followed by grand mean scaling to 50.

To compare changes in rCMRglc between the two groups, group-by-time interaction effects were tested on a voxel-by-voxel basis. The voxel-wise significance threshold was set at p < 0.005 with a minimum cluster size of 100 contiguous voxels.

Computational modeling

When applying tDCS, the current distribution may be partially influenced by stimulation parameters and anatomical characteristics of the brain. Thus, computational modelling was performed to verify that the current reaches the targeted brain regions. Finite element method (FEM) models of two older adults of Asian ethnicity (S12, S13) from the ADNI database (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI) were created to predict cortical electric field generated during tDCS. High-resolution T1-weighted images were segmented into six tissue/material masks by adapting the ROAST pipeline [31] for older adult anatomy. Segmentation initiated with SPM 8 [32] and automatic touch-up on the segmentation results were performed. Residual errors were patched by manual segmentation (ScanIP, Synopsys Inc., Mountain View, USA). Previously validated compartment conductivities were assigned, virtual bilateral (F3, F4) electrodes positioned and energized (left electrode: 2 mA inward current; right electrode: ground) corresponding to the experimental dose, and volumetric anatomy converted to mesh for numerically solving the Laplace equation [33].

Statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between the groups. Linear mixed models with robust standard errors were used to test for group-by-time interaction effects on cognitive test scores. To check the robustness of the models, the residuals were tested for normality by visual inspection and Shapiro-Wilk tests. In case of skewed residuals, Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to compare pre-post changes between two groups. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the exploratory character of the current study, no correction for multiple comparisons was made. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

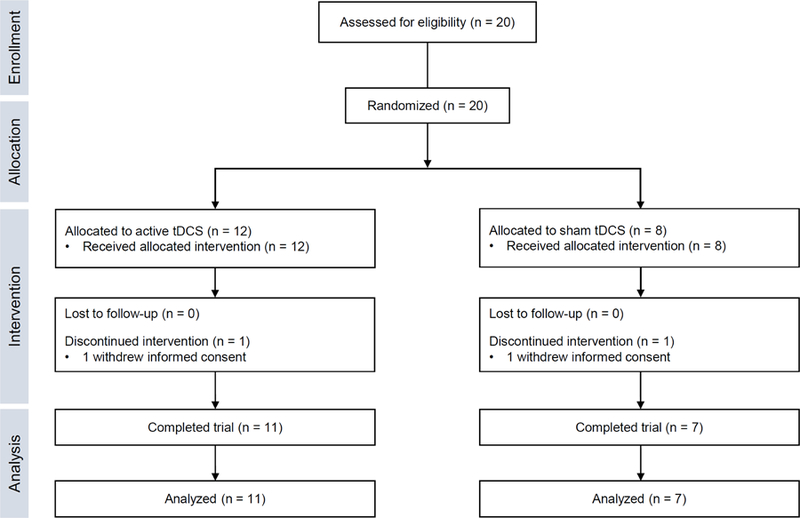

A total of 20 patients with early AD were recruited and randomized into either the active tDCS group (n = 12) or the sham tDCS group (n = 8). Two participants dropped out of the study due to refusal or time conflict of a care giver (one in the active group and one in the sham group). Thus, 11 participants in the active group and 7 participants in the sham group completed the study and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants who completed the study are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups in baseline characteristics including age, sex, education, handedness, MMSE, CDR, and CDR-SOB.

Figure 1. Flow diagram.

tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participantsa

| Characteristics | Treatment groups |

Test statisticb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active tDCS (n = 11) | Sham tDCS (n = 7) | ||

| Age, years | 71.9 ± 9.2 | 74.9 ± 5.0 | z = −0.41, p = 0.68 |

| Female:male, n | 10:1 | 5:2 | p = 0.33 |

| Education, years | 6.3 ± 3.8 | 5.4 ± 5.9 | z = 0.60, p = 0.55 |

| Right handedness, n | 11 | 7 | |

| MMSE | 20.1 ± 3.8 | 22.1 ± 4.6 | z = −1.32, p = 0.19 |

| CDR | p = 1.00 | ||

| 0.5 | 10 | 7 | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| CDR-SOB | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | z = 0.24, p = 0.81 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n.

Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CDR-SOB, Clinical Dementia Rating - Sum of Boxes; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Effects of tDCS on cognitive performance

Results from cognitive assessments at baseline and follow-up are presented in Table 2. There were no significant baseline differences in any individual tests between the groups.

Table 2.

Results of neuropsychological tests before and after 6-month transcranial direct current stimulationa

| Test | Active tDCS (n=11) |

Sham tDCS (n=7) |

p (baseline)b | p (interaction) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |||

| MMSE | 20.1 ± 3.8 | 21.2 ± 4.4 | 22.1 ± 4.6 | 20.6 ± 4.5 | 0.19 | 0.02c |

| Attention | ||||||

| DST: forward | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 0.13 | 0.12c |

| DST: backward | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 0.60 | 0.88c |

| Language | ||||||

| BNT | 28.3 ± 12.7 | 32.0 ± 13.3 | 26.4 ± 10.8 | 26.6 ± 9.6 | 0.82 | 0.04c |

| Repetition | 14.8 ± 0.4 | 14.8 ± 0.4 | 14.1 ± 1.9 | 14.4 ± 1.1 | 0.53 | 0.44d |

| Visuospatial Function | ||||||

| RCFT: copy | 26.2 ± 9.5 | 21.8 ± 12.1 | 19.1 ± 13.3 | 21.4 ± 8.3 | 0.17 | 0.08c |

| Clock Drawing Test | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 0.92 | 0.63c |

| Memory | ||||||

| SVLT: immediate recall | 12.3 ± 5.3 | 13.1 ± 5.2 | 9.3 ± 5.3 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 0.19 | 0.07c |

| SVLT: delayed recall | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 2.0 ± 3.1 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.06 | 0.16c |

| SVLT: recognition | 15.1 ± 5.9 | 15.6 ± 4.0 | 17.7 ± 1.4 | 16.6 ± 4.0 | 0.27 | 0.44d |

| RCFT: immediate recall | 2.6 ± 3.8 | 3.2 ± 2.9 | 3.5 ± 3.7 | 4.0 ± 4.7 | 0.30 | 0.49d |

| RCFT: delayed recall | 3.3 ± 4.9 | 3.3 ± 4.1 | 1.4 ± 3.4 | 3.0 ± 3.9 | 0.55 | 0.48d |

| RCFT: recognition | 14.1 ± 5.4 | 15.2 ± 3.5 | 17.3 ± 2.2 | 15.6 ± 1.9 | 0.14 | 0.15d |

| Executive Function | ||||||

| Contrasting Program | 15.5 ± 6.9 | 15.5 ± 6.9 | 14.3 ± 7.9 | 10.3 ± 7.8 | 0.75 | 0.07d |

| Go-no go Test | 15.7 ± 5.9 | 15.3 ± 7.1 | 10.7 ± 7.4 | 8.3 ± 8.3 | 0.12 | 0.36c |

| COWAT: animal | 8.8 ± 4.0 | 8.9 ± 3.3 | 8.1 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 0.49 | 0.65c |

| COWAT: supermarket | 10.5 ± 5.7 | 11.4 ± 5.9 | 7.4 ± 5.7 | 7.7 ± 4.6 | 0.25 | 0.78c |

| COWAT: phonemic | 12.9 ± 8.4 | 12.9 ± 8.4 | 14.7 ± 9.7 | 14.7 ± 9.7 | 0.96 | 0.71c |

| Stroop Test: word reading | 91.4 ± 32.8 | 85.2 ± 36.3 | 97.8 ± 23.1e | 66.7 ± 25.5e | 0.77 | 0.09d |

| Stroop Test: color reading | 41.7 ± 28.6 | 39.5 ± 33.6 | 45.5 ± 26.5e | 50.8 ± 32.7e | 0.61 | 0.46c |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

p for comparisons of baseline scores using Mann-Whitney test

p for group-by-time interaction from linear mixed model

Mann-Whitney test for changes between groups due to skewed residuals of linear mixed model

n = 6

BNT, Boston Naming Test; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; DST, Digit Span Test; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; RCFT, Rey Complex Figure Test; SVLT, Seoul Verbal Learning Test; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

After tDCS sessions, scores of MMSE (p for interaction = 0.02) and BNT (p for interaction = 0.04) were improved in the active tDCS group compared to the sham group. In addition, the active tDCS stabilized some measures of executive function including Contrasting Program (p for interaction = 0.07) and Stroop word reading test (p for interaction = 0.09) at a marginal level, while these scores were decreased in the sham group.

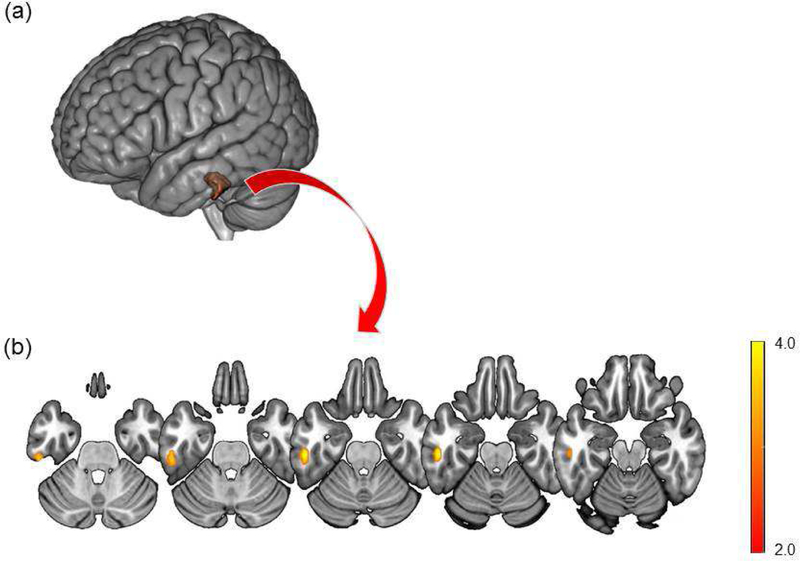

Effects of tDCS on rCMRglc

In comparison of changes in rCMRglc between the two groups, a significant group-by-time interaction effect was found in the left middle/inferior temporal gyrus (peak t = 4.70, peak p < 0.001, peak coordinates = −54, −24, −24, cluster size = 135 voxels; Fig. 2). The relative rCMRglc from this significant cluster remained stable in the active group (67.3 ± 8.3 to 67.7 ± 7.9), but decreased in the sham group (76.6 ± 9.4 to 72.7 ± 10.5).

Figure 2.

Brain areas with significant group-by-time interaction effects of regional cerebral glucose metabolism are overlaid on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 template rendered in (a) 3D and (b) axial slices. Images are displayed in neurological convention. Color bar represents the voxel-level t-values.

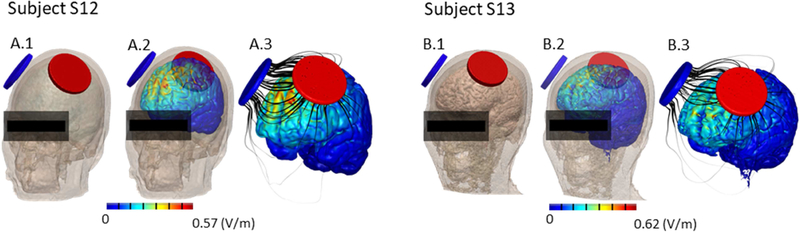

High-resolution computational models

The induced electric field magnitude was calculated across the cortical surface using high-resolution subject-specific models (Fig. 3). The distribution of electric field across the frontal cortex and peak magnitudes (Subject S12: 0.57 V/m. Subject S13: 0.62 V/m) were within the range previously reported for adults [34, 35].

Figure 3.

Prediction of cortical current and electrical field during transcranial direct current stimulation using the F3-F4 montage (6 cm diameter electrodes, anode left) in two older adults of Asian ethnicity (S12, S13). A.1 and B.1 show the montage on the subjects, while A.2, A.3, B.2, and B.3 show the electric field maps (false color) and flux lines (black) generated across outer cortical regions.

Discussion

The current study investigated effects of home-based daily tDCS in the DLPFC over 6 months on cognition among patients with early-stage AD. In addition, we tried to examine underlying neural correlates of tDCS treatment using FDG-PET. Our findings indicate that the tDCS have significant beneficial effects on global cognition, language function, and rCMRglc in AD patients.

First, we found improved global cognitive performance assessed by the MMSE after active tDCS. Particularly, the mean MMSE score was increased by 1.1 points in the active group, whereas it was decreased by 1.5 points in the sham group over the 6-month treatment period. As reported previously, MMSE score is expected to decline 2 to 4 points per year in untreated patients with mild to moderate AD [36, 37]. Considering the expected annual decline of MMSE score, our finding may suggests that repeated tDCS over 6 months not only prevents the decline of global cognitive functioning but also improves it in patients with early-stage AD. Our findings are in line with the previous study, whereby 10 daily sessions of tDCS enhanced MMSE scores in AD patients [16]. However, since the MMSE was originally developed as a brief screening instrument, our result should be cautiously interpreted with other cognitive and neuroimaging findings.

Scores of BNT was also increased in the active tDCS group compared to the sham group. Anomia is commonly found in the early stage of AD. A previous study in healthy adults reported that anodal tDCS of the left DLPFC enhanced naming performance and this effect was not due to a general increase in arousal [38]. In addition, high-frequency repetitive TMS of the left and right DLPFC improved accuracy in action naming in AD patients [39]. These results suggest that the DLPFC may be a part of the cerebral network involved in lexical retrieval and selection processing in naming and tDCS over this region can ameliorate language deficits in patients with AD.

At a trend-level significance, performances in executive function and attention (Contrasting Program and Stroop word reading test) remained stable in the active tDCS group in contrast to reductions in the sham group. Besides memory impairment, executive and attentional deficits are thought to be integral components of the cognitive dysfunction in AD and these deficits are usually one of the earliest cognitive domains to be affected in AD patients [40–42]. Moreover, deficits in executive functioning and attention, key indicators of need for supervision and care among AD patients, are closely linked to inability to carry out daily activities and caregiver burden [40, 43]. However, changes in delayed recall performance was not significantly different between the two groups, although an impairment in this function is one of the core characteristics of early AD. In addition, group-by-time interaction effects of RCFT copy and SVLT immediate recall also showed a marginal significance in favor of the sham group. These results may be due to the small sample size and relatively lower baseline scores in the sham group although the baseline differences were not significant.

Compared to the sham tDCS, the active treatment prevented decreases of rCMRglc in the left middle/inferior temporal gyrus. These areas have important interconnections with medial temporal cortex and are affected in early pathological stages of AD [44]. Furthermore, atrophy in the lateral temporal lobe was found in AD patients and correlated with the severity of memory and language deficits [45]. A previous FDG-PET study in early AD patients demonstrated associations between verbal semantic memory and rCMRglc in the left inferior temporal gyrus [46] Effects of tDCS have been known to spread beyond the target site [47]. In this study, tDCS may have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism in the middle/inferior temporal regions and, in turn, cognitive functions. Potential mechanisms of tDCS on neural activity include NMDA receptors and dopaminergic and serotonergic systems [48]. In addition, a previous study using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy suggested that anodal tDCS increases cellular consumption of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and synthesis of ATP and phosphocreatine by mitochondria [49].

Our study has some limitations. First, the small sample size and the unequal number of patients in each group might decrease the statistical power. Second, all patients were taking medication for AD during the study period. Although the medication status was not different between the groups, possible medication effects cannot be ruled out. Third, we did not check at the end of the study whether the patients or caregivers noticed the stimulation type from evoked sensations. Lastly, multiple comparison corrections were not applied for the analysis. Thus, further studies should use more stringent statistical thresholds.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that home-based daily tDCS over 6 months may be beneficial for global cognitive performance, language function, and rCMRglc in patients with early-stage AD, suggesting the therapeutic potential of repeated at-home tDCS. Our findings are preliminary and need to be replicated in larger samples with longer follow-up periods.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examined effects of 6-month at-home tDCS over the DLPFC in AD patients.

tDCS improved global cognition and language function.

tDCS prevented decreases in glucose metabolism in the middle/inferior temporal gyrus.

Repeated at-home tDCS may be a promising treatment option for AD.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2015M3C7A1064832, 2017R1C1B2011802) and by the National Institutes of Health (NIHNIMH 1R01MH111896, NIH-NINDS 1R01NS101362).

Financial Disclosures

The City University of New York (CUNY) has IP on neurostimulation system and methods with Marom Bikson as inventor. Marom Bikson has equity in Soterix Medical Inc and serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All other authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018;14(3):367–429. [Google Scholar]

- [2].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, Priori A, Lang N, Antal A, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimul 2008;1(3):206–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Poreisz C, Boros K, Antal A, Paulus W. Safety aspects of transcranial direct current stimulation concerning healthy subjects and patients. Brain Res Bull 2007;72(4–6):208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Roncero C, Kniefel H, Service E, Thiel A, Probst S, Chertkow H. Inferior parietal transcranial direct current stimulation with training improves cognition in anomic Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3(2):247–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Boggio PS, Ferrucci R, Mameli F, Martins D, Martins O, Vergari M, et al. Prolonged visual memory enhancement after direct current stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Stimul 2012;5(3):223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ferrucci R, Mameli F, Guidi I, Mrakic-Sposta S, Vergari M, Marceglia S, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation improves recognition memory in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008;71(7):493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Frith C, Dolan R. The role of the prefrontal cortex in higher cognitive functions. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 1996;5(1–2):175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rossi S, Innocenti I, Polizzotto NR, Feurra M, De Capua A, Ulivelli M, et al. Temporal dynamics of memory trace formation in the human prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 2011;21(2):368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hawco C, Berlim MT, Lepage M. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a role in self-initiated elaborative cognitive processing during episodic memory encoding: rTMS evidence. PLoS One 2013;8(9):e73789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dockery CA, Hueckel-Weng R, Birbaumer N, Plewnia C. Enhancement of planning ability by transcranial direct current stimulation. J Neurosci 2009;29(22):7271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fregni F, Boggio PS, Nitsche M, Bermpohl F, Antal A, Feredoes E, et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Exp Brain Res 2005;166(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iyer MB, Mattu U, Grafman J, Lomarev M, Sato S, Wassermann EM. Safety and cognitive effect of frontal DC brain polarization in healthy individuals. Neurology 2005;64(5):872–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Javadi AH, Cheng P. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) enhances reconsolidation of long-term memory. Brain Stimul 2013;6(4):668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Boggio PS, Khoury LP, Martins DC, Martins OE, de Macedo EC, Fregni F. Temporal cortex direct current stimulation enhances performance on a visual recognition memory task in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80(4):444–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Khedr EM, Gamal NF, El-Fetoh NA, Khalifa H, Ahmed EM, Ali AM, et al. A double-blind randomized clinical trial on the efficacy of cortical direct current stimulation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2014;6:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Penolazzi B, Bergamaschi S, Pastore M, Villani D, Sartori G, Mondini S. Transcranial direct current stimulation and cognitive training in the rehabilitation of Alzheimer disease: A case study. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2015;25(6):799–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bystad M, Rasmussen ID, Gronli O, Aslaksen PM. Can 8 months of daily tDCS application slow the cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease? A case study. Neurocase 2017;23(2):146–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Knotkova H, Clayton A, Stevens M, Riggs A, Charvet LE, Bikson M. Home-Based Patient-Delivered Remotely Supervised Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Practical Guide to Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Springer; 2019, p. 379–405. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Varghese T, Sheelakumari R, James JS, Mathuranath P. A review of neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Asia 2013;18(3):239–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yun K, Song IU, Chung YA. Changes in cerebral glucose metabolism after 3 weeks of noninvasive electrical stimulation of mild cognitive impairment patients. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016;8(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Owen AM, McMillan KM, Laird AR, Bullmore E. N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2005;25(1):46–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jacobson L, Koslowsky M, Lavidor M. tDCS polarity effects in motor and cognitive domains: a meta-analytical review. Exp Brain Res 2012;216(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kwon YH, Jang SH. Onsite-effects of dual-hemisphere versus conventional single-hemisphere transcranial direct current stimulation: A functional MRI study. Neural Regen Res 2012;7(24):1889–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lindenberg R, Nachtigall L, Meinzer M, Sieg MM, Floel A. Differential effects of dual and unihemispheric motor cortex stimulation in older adults. J Neurosci 2013;33(21):9176–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [27].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34(7):939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc 1997;15(2):300–8. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989;39(9):1159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Minoshima S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. Preserved pontine glucose metabolism in Alzheimer disease: a reference region for functional brain image (PET) analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995;19(4):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huang Y, Datta A, Bikson M, Parra LC. Realistic vOlumetric-Approach to Simulate Transcranial Electric Stimulation--ROAST--a fully automated open-source pipeline. bioRxiv 2017:217331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 2005;26(3):839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Datta A, Bansal V, Diaz J, Patel J, Reato D, Bikson M. Gyri-precise head model of transcranial direct current stimulation: improved spatial focality using a ring electrode versus conventional rectangular pad. Brain Stimul 2009;2(4):201–7, 7 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Datta A, Truong D, Minhas P, Parra LC, Bikson M. Inter-Individual Variation during Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation and Normalization of Dose Using MRI-Derived Computational Models. Front Psychiatry 2012;3:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Seibt O, Brunoni AR, Huang Y, Bikson M. The Pursuit of DLPFC: Non-neuronavigated Methods to Target the Left Dorsolateral Pre-frontal Cortex With Symmetric Bicephalic Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Brain Stimul 2015;8(3):590–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brooks JO 3rd, Yesavage JA, Taylor J, Friedman L, Tanke ED, Luby V, et al. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: elaborating on the nature of the longitudinal factor structure of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Int Psychogeriatr 1993;5(2):135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Salmon DP, Thal LJ, Butters N, Heindel WC. Longitudinal evaluation of dementia of the Alzheimer type: a comparison of 3 standardized mental status examinations. Neurology 1990;40(8):1225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fertonani A, Rosini S, Cotelli M, Rossini PM, Miniussi C. Naming facilitation induced by transcranial direct current stimulation. Behav Brain Res 2010;208(2):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cotelli M, Manenti R, Cappa SF, Geroldi C, Zanetti O, Rossini PM, et al. Effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation on action naming in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2006;63(11):1602–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Perry RJ, Hodges JR. Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review. Brain 1999;122 ( Pt 3):383–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Baudic S, Barba GD, Thibaudet MC, Smagghe A, Remy P, Traykov L. Executive function deficits in early Alzheimer’s disease and their relations with episodic memory. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2006;21(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Binetti G, Magni E, Padovani A, Cappa SF, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M. Executive dysfunction in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60(1):91–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Patterson MB, Mack JL, Geldmacher DS, Whitehouse PJ. Executive functions and Alzheimer’s disease: problems and prospects. Eur J Neurol 1996;3(1):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82(4):239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pantel J, Schroder J, Schad LR, Friedlinger M, Knopp MV, Schmitt R, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological functions in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Psychol Med 1997;27(1):221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, Imamura T, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, et al. Neuronal substrates for semantic memory: a positron emission tomography study in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2001;12(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Nitsche MA. Beyond the target area: remote effects of non-invasive brain stimulation in humans. J Physiol 2011;589(Pt 13):3053–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Stagg CJ, Nitsche MA. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 2011;17(1):37–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rae CD, Lee VH, Ordidge RJ, Alonzo A, Loo C. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation increases brain intracellular pH and modulates bioenergetics. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16(8):1695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.