Abstract

Antiretroviral therapy is successfully administered to people living with HIV while they are incarcerated in most U.S. prison systems, but interruptions in treatment are common after people are released. We undertook an observational cohort study designed to examine the clinical and psychosocial factors that influence linkage to HIV care and viral suppression after release from a single state prison system. In this report we describe baseline characteristics and 6-month post-incarceration HIV care outcomes for 170 individuals in Wisconsin. Overall, 114 (67%) individuals were linked to outpatient HIV care within 180 days of release from prison, and of these, 90 (79%) were observed to have HIV viral suppression when evaluated in the community. The strongest predictor of linkage to care in this study was participation in a patient navigation program: Those who received patient navigation were linked to care 84% of the time, compared to 60% of the individuals who received only standard release planning (adjusted OR=3.69, 95% CI: 1.24, 10.96; P<0.01). Findings from this study demonstrate that building and maintaining intensive patient navigation programs that support individuals releasing from prison is beneficial for improving transitions in HIV care.

Keywords: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Linkage to Care, Viral Suppression, Incarceration, Reentry

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a chronic viral infection requiring sustained access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in order to prevent viral transmission and progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Globally, incarcerated persons represent a key priority population for HIV control efforts because of their high prevalence of HIV and comorbidities such as viral hepatitis and tuberculosis [1]. There is also a high concentration of transmission risk behaviors in criminal justice settings, creating environments which can fuel the HIV epidemic and thwart population-level interventions to reduce HIV transmission [2].

In the United States, criminal justice-involved adults have a substantially higher prevalence of HIV infection than the general population [3]. ART is widely available for infected individuals incarcerated in state and federal prisons in the United States, although access to ART is less well documented and may be sporadic in many local jails and other short-term detention facilities. Prior studies have shown that patients treated for HIV while in prison tend to have comparable treatment outcomes to people treated in community-based clinics [4, 5]. Other studies have documented, however, that continuity of HIV care is extremely poor for people who are released from prison and must transition from prison-based care to a community-based provider. In this context, patients often miss HIV-related clinical appointments [6], experience frequent lapses in treatment adherence [7, 8] and develop virologic failure [6, 9].

Improving care for people living with HIV (PLWH) following incarceration is important for the health of these individuals and the communities to which they return. Antiretroviral treatment interruptions can lead to higher community rates of HIV transmission and can increase the prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance [10]. Optimizing the HIV care continuum by ensuring efficient linkage to care for PLWH, providing universal access to ART and promoting uninterrupted medication adherence, is viewed as the foundation of global programs striving to end the HIV epidemic [11]. Addressing continued management of HIV infections within formerly incarcerated people upon community re-entry has been identified as a critically important component of these efforts [12, 13].

The process of community re-entry poses significant challenges to managing HIV, including risk of substance use relapse, poor access to mental health care, and lack of employment, housing, transportation, and education [14, 15]. The purpose of this study is to describe the HIV care experiences and outcomes of a cohort of criminal justice-involved adults living with HIV as they transition to community life during the first six months after release from prison. By enhancing our understanding of the specific challenges encountered during this critically important period, this study aims to inform the development of future interventions and policy changes that can improve retention in HIV care. In this report, we describe baseline characteristics and post-release HIV outcomes for participants in this cohort.

Methods

Study setting

Wisconsin is a medium-sized state in the Great Lakes region of the United States, with a low-to-moderate HIV prevalence. In 2017, there were 7,123 people living with diagnosed HIV in Wisconsin [16], corresponding to a prevalence rate of 121 per 100,000 persons. Despite an overall low HIV prevalence, Wisconsin has substantial racial and geographic disparities. Milwaukee County, the state’s main urban center, accounts for 17% of the state’s population but 51% of all new HIV diagnoses [16, 17]. The HIV diagnosis rate among Black men in Wisconsin is 13-fold greater than that of White men, and the diagnosis rate among Black women in Wisconsin is 22-fold greater than White women [16]. Wisconsin also has the United States’ widest racial disparity in the rate of incarceration [18], making it a valuable context in which to study social factors influencing the HIV care continuum.

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections (WI DOC) houses an adult prison population of approximately 22,600 individuals, with an estimated HIV prevalence of 7 per 1,000 incarcerated persons [19]. PLWH in WI DOC prisons receive clinical care at the University of Wisconsin HIV/AIDS Comprehensive Care Clinic (UWCCC), which also served as the venue for recruiting participants for this study. The standard of care at WI DOC is for individuals to be dispensed a 30 day supply of all chronically-prescribed medications at the time of release, and this practice remained constant throughout the study period.

Study participants

In this retrospective cohort study, individuals were included if they were released from a Wisconsin state prison between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015 and met the following inclusion criteria: (1) were 18 years of age or older, (2) could speak and understand English, (3) were incarcerated for at least 30 days, and (4) received ART for HIV infection while incarcerated.

Data Collection

Using a standardized data collection form, researchers collected past medical history from the UWCCC electronic health record (EHR) system, including dates of HIV/AIDS-related diagnoses, receipt of antiretroviral medications, and prior diagnoses of co-morbid chronic medical conditions, mental health problems and substance use disorders. To create a comprehensive record of prior HIV care for each participant, data were extracted from clinic encounters occurring during the period of incarceration, during prior instances of incarceration outside the study period, and during health care encounters at UWCCC occurring at times when the participant was not incarcerated.

After executing a data use agreement with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) and establishing a mechanism for secure, encrypted and HIPAA-compliant data transfer, we obtained participant-level data contained in the enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS) database. eHARS data were used to describe demographic characteristics, risk behaviors obtained at the time of initial diagnosis, and all subsequent laboratory data (i.e. quantitative HIV RNA levels) reported through mandated laboratory-based reporting. DHS also queried vital records and provided dates of death for deceased study participants.

Data describing periods of incarceration were obtained through a data sharing agreement with WI DOC. Again using an encrypted file transfer protocol, WI DOC staff provided dates of admission and release from all Wisconsin prisons for all study participants. This allowed us to define the period(s) of time that each participant was incarcerated, and ultimately to determine whether individuals were engaging in HIV care and adhering to ART after periods of incarceration. For cases where participants were incarcerated multiple times during the study period, we evaluate in this paper the outcomes related to the most recent eligible incarceration period.

The study protocol was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the Wisconsin Department of Corrections Research Committee. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained through the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Study Outcomes

We used eHARS surveillance data to define two main study outcomes. The first, linkage to care, was defined as having the results of a quantitative HIV RNA test obtained at any community-based provider reported to eHARS within 180 days of release from prison. The second outcome, viral suppression, was measured as a validated indicator of medication adherence [20]. Viral suppression was ascertained only for participants who achieved linkage to care, and was defined as having an HIV RNA level less than 200 copies/mL for all quantitative HIV RNA tests reported within 180 days of release from prison (with a minimum of one test reported). For participants who were re-incarcerated within 180 days of release, linkage to care and viral suppression were assessed only during the period in which they resided in the community. That is, HIV RNA test results reported to eHARS that corresponded to a date on which a participant was residing in a WI DOC facility did not constitute evidence of linkage to care.

Covariates considered as potential predictors of post-release engagement in care included the clinical and behavioral variables obtained through UWCCC chart reviews, demographic and pre-release viral suppression obtained using eHARS, and prison release year obtained from the WI DOC database. Individuals were considered virally suppressed prior to release from prison if the last HIV RNA laboratory result reported prior to their release occurred during their incarcerated period and was less than 200 copies/mL. In addition to these, we considered whether participants enrolled in an intensive case management program designed to improve retention in care for vulnerable patients, named the WI Linkage to Care Program [17]. Beginning in June 2013, incarcerated PLWH being released to one of the two largest cities in Wisconsin, Madison and Milwaukee, were invited to enroll in this time-limited, high-contact, patient navigation model that provided support for medical appointment access and management, treatment adherence, housing, social services, emotional wellbeing, and health education, as described in detail previously [21]. This initiative, along with similar efforts in five other states, were supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Special Projects of National Significance Program’s Systems Linkages and Access to Care for Populations at High Risk of HIV Infection Initiative. Lastly, between October 2013 and December 2015, a subset of participants participated in a prospective, mixed-methods study aiming to investigate in-depth the transitional care experiences of PLWH after release from prison. Participation in this study involved receipt of a mobile phone and monthly telephone interviews for six months following release from prison. The methods and qualitative findings of this sub-study have been reported previously [22, 23]. Acknowledging that the WI Linkage to Care Program and this prospective research study likely influence linkage to care and viral suppression, we included participation in these programs as independent variables in our analysis.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics and main study outcomes were calculated using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Bivariate analyses were conducted to assess whether any individual characteristics were independently associated with the two main study outcomes, linkage to care and viral suppression, using Pearson chi-square (when all expected cell sizes are > 5) or Fisher Exact tests (when one or more expected cell sizes are ≤ 5) for categorical variables, and the two-sample unpaired t-test (when normally distributed) or the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (when non-normally distributed) for continuous variables. For individuals who experienced more than one incarceration during the study timeframe, we used eHARS viral load data corresponding to the last incarceration period that lasted at least 30 days during the study timeframe (January 1, 2011-December 31,2015). Variables that were at least suggestive to be independent predictors of linkage to care and viral suppression (P≤0.2) were considered candidates for analysis using multiple logistic regression. To evaluate whether any characteristics influence how promptly individuals were linked to care after release from prison, we created survival plots using Kaplan-Meier estimation to compare the time elapsed between the date of release and the first evidence of HIV care engagement across subgroups of participants defined by characteristics determined to be statistically significantly associated with linkage to care (P≤0.05). Re-incarcerated individuals with no HIV RNA tests reported prior to re-incarceration were censored. All other individuals were assumed to be living in the community and eligible for linkage to care for 180 days, unless the vital records data showed a date of death during this time period. Individuals who did not die or receive a HIV RNA test 180 days after release from prison (i.e. did not achieve HIV linkage to care) were administratively censored.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015, there were 170 unique individuals who were released one or more times from a WI DOC prison after being incarcerated for at least 30 days. The median length of stay in prison, not including prior or future incarcerations, was 541 days (1.5 years), ranging from 32 to 6,951 days (19.0 years). Eleven individuals were re-incarcerated within 180 days of release from prison. Re-incarceration among these 11 individuals occurred from 16 to 169 days after release (mean: 76 days). No deaths occurred among this population within 180 days of release from prison.

Baseline descriptive characteristics of the study population are displayed in Table I. The sample was 91% male and 58% Black/African-American. The mean age was 41, ranging from 20 to 68. The primary mode of HIV transmission reported was heterosexual contact (42%), followed by male-to-male sexual contact (31%) and injection drug use (17%). Of the 170 individuals included in this analysis, 146 (86%) had a viral load laboratory result in eHARS prior to their release from prison, of which 126 (86%) were virally suppressed at this time. The majority of the sample had never been diagnosed with AIDS (72%) and were receiving ART (57%) prior to incarceration. The most commonly identified co-morbid chronic diseases were hypertension (22%) and hepatitis C infection (19%). Depression (37%) and anxiety (20%) were the most commonly listed mental health problems.

Table I.

Description of cohort (N=170)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 155 (91.2) |

| Cisgender female | 11 (6.5) |

| Transgender female | 4 (2.4) |

| Age at release from prison | |

| 20-29 | 19 (11.2) |

| 30-39 | 52 (30.6) |

| 40-49 | 71 (41.8) |

| 50-59 | 21 (12.4) |

| 60-68 | 7 (4.1) |

| Prison release year | |

| 2011 | 25 (14.7) |

| 2012 | 36 (21.2) |

| 2013 | 35 (20.6) |

| 2014 | 37 (21.8) |

| 2015 | 37 (21.8) |

| Race | |

| Black/African-American | 98 (57.6) |

| White/Caucasian | 57 (33.5) |

| Native American | 7 (4.1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (1.2) |

| Other | 6 (3.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 158 (92.9) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (7.1) |

| IDU | |

| No | 139 (81.8) |

| Yes | 31 (18.2) |

| MSM | |

| No | 114 (67.1) |

| Yes | 56 (32.9) |

| Chronic disease diagnoses | |

| COPD | 5 (2.9) |

| Cirrhosis | 0 (0.0) |

| Cancer | 6 (3.5) |

| Diabetes | 8 (4.7) |

| Heart Disease | 5 (2.9) |

| Hepatitis B | 7 (4.1) |

| Hepatitis C | 33 (19.4) |

| Hypertension | 38 (22.4) |

| Kidney Disease | 6 (3.5) |

| Mental health diagnoses | |

| Anxiety or panic disorder | 34 (20.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 21 (12.4) |

| Depression | 62 (36.5) |

| Psychotic disorder | 2 (1.2) |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (4.1) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 17 (10.0) |

| Opioid use disorder | 18 (10.6) |

| Cocaine use disorder | 28 (16.5) |

| Methamphetamine use disorder | 3 (1.8) |

| Number of diagnoses | |

| At least 1 chronic disease diagnosis | 73 (42.9) |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosis | 97 (57.1) |

| 3 or more total diagnoses | 47 (27.6) |

| Virally suppressed prior to release from prisona | |

| No | 20 (13.7) |

| Yes | 126 (86.3) |

| Ever had AIDS-defining conditiona | |

| No | 121 (71.6) |

| Yes | 48 (28.4) |

| Received HIV care prior to incarcerationa | |

| No | 68 (40.5) |

| Yes | 100 (59.5) |

| Participated in prospective research study | |

| No | 120 (70.6) |

| Yes | 50 (29.4) |

| Enrolled in WI Linkage to Care Program | |

| No | 119 (70.0) |

| Yes | 51 (30.0) |

Missing pre-release viral load data for 24 individuals, AIDS data for one individual and prior HIV care data for two individuals.

Main Study Outcomes

Of 170 individuals released from prison during the study, 114 (67%) were linked to care within 180 days of release from prison. Of the 11 individuals who were re-incarcerated within 180 days, six were linked to care prior to re-incarceration. Associations between baseline characteristics and linkage to care are displayed in Table II. Bivariate analyses revealed that individuals who ever enrolled in the WI Linkage to Care Program (n=51) were significantly more likely to be linked to care compared to those who never enrolled (84% vs 60%, P=0.002). Similarly, individuals who participated in the prospective research study were significantly more likely to be linked to care compared to those who did not (78% vs 63%, P=0.050). Individuals who were virally suppressed before release from prison were significantly more likely to be linked to care in the community than those with elevated HIV RNA prior to release (76% vs 55%, P=0.047). Of the 11 individuals who were not virally suppressed prior to release and who linked to care in the community within 180 days, six remained unsuppressed at the time of the linkage and five had achieved viral suppression. Although not statistically significant, we observed a trend toward improved linkage to care among individuals released from prison in later years of the study (P=0.077).

Table II.

Associations between individual characteristics and linkage to care (N=170)

| Characteristic | Linked to care, N (%a) | Not Linked to care, N (%a) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 114 (67.1) | 56 (32.9) | |

| Prison release year | |||

| 2011 (N=25) | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) | 0.077 |

| 2012 (N=36) | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | |

| 2013 (N=35) | 25 (71.4) | 10 (28.6) | |

| 2014 (N=37) | 26 (70.3) | 11 (29.7) | |

| 2015 (N=37) | 27 (73.0) | 10 (27.0) | |

| Male | |||

| No (N=15) | 9 (60.0) | 6 (40.0) | 0.572 |

| Yes (N=155) | 105 (67.7) | 50 (32.3) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 42 (9.8) | 41 (9.2) | 0.468 |

| Black/African-American | |||

| No (N=72) | 45 (62.5) | 27 (37.5) | 0.278 |

| Yes (N=98) | 69 (70.4) | 29 (29.6) | |

| Duration of incarceration | |||

| ≤365 days (N=56) | 35 (62.5) | 21 (37.5) | 0.375 |

| >365 days (N=114) | 79 (69.3) | 35 (30.7) | |

| IDU | |||

| No (N=139) | 91 (65.5) | 48 (34.5) | 0.350 |

| Yes (N=31) | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | |

| MSM | |||

| No (N=114) | 77 (67.5) | 37 (32.5) | 0.848 |

| Yes (N=56) | 37 (66.1) | 19 (33.9) | |

| At least 1 chronic disease diagnosis | |||

| No (N=97) | 66 (68.0) | 31 (32.0) | 0.753 |

| Yes (N=73) | 48 (65.8) | 25 (34.2) | |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosis | |||

| No (N=73) | 49 (67.1) | 24 (32.9) | 0.988 |

| Yes (N=97) | 65 (67.0) | 32 (33.0) | |

| At least 3 comorbid conditions | |||

| No (N=123) | 86 (69.9) | 37 (30.1) | 0.199 |

| Yes (N=47) | 28 (59.6) | 19 (40.4) | |

| Virally suppressed prior to release from prisonb | |||

| No (N=20) | 11 (55.0) | 9 (45.0) | 0.047 |

| Yes (N=126) | 96 (76.2) | 30 (23.8) | |

| Diagnosed with AIDSb | |||

| No (N=121) | 81 (66.9) | 40 (33.1) | 0.973 |

| Yes (N=48) | 32 (66.7) | 16 (33.3) | |

| Received HIV care prior to incarcerationb | |||

| No (N=68) | 44 (64.7) | 24 (35.3) | 0.560 |

| Yes (N=100) | 69 (69.0) | 31 (31.0) | |

| Participated in a prospective research study | |||

| No (N=120) | 75 (62.5) | 45 (37.5) | 0.050 |

| Yes (N=50) | 39 (78.0) | 11 (22.0) | |

| Enrolled in WI Linkage to Care Program | |||

| No (N=119) | 71 (59.7) | 48 (40.3) | 0.002 |

| Yes (N=51) | 43 (84.3) | 8 (15.7) |

Percentages present the proportion linked to care / not linked to care with that characteristic.

Missing pre-release viral load data for 24 individuals, AIDS data for one individual and prior HIV care data for two individuals.

In an analysis limited to the 114 individuals linked to care within 180 days, 90 (79%) participants were determined to have achieved HIV viral suppression, indicating sustained adherence to ART during the transition period. As shown in Table III, the only variable significantly predictive of viral suppression after release from prison is viral suppression prior to release (94% vs 75%, P=0.007). We also observed a trend toward increased viral suppression among participants within several subgroups: Participants who were Black/African-American (84% vs 71%, P=0.097), those who had never received an AIDS diagnosis (83% vs 69%, P=0.102), and those who received HIV care for the first time while in prison (86% vs 74%, P=0.115), all appeared more likely to have viral suppression after they were released.

Table III.

Associations between individual characteristics and viral suppression among those linked to care (N=114)

| Characteristic | Virally Suppressed, N (%a) | Not Virally Suppressed, N (%a) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 90 (78.9) | 24 (21.1) | |

| Prison release year | |||

| 2011 (N=12) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0.619 |

| 2012 (N=24) | 19 (79.2) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 2013 (N=25) | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | |

| 2014 (N=26) | 21 (80.8) | 5 (19.2) | |

| 2015 (N=27) | 21 (77.8) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Male | |||

| No (N=9) | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0.682 |

| Yes (N=105) | 82 (78.1) | 23 (21.9) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 42 (10.1) | 43 (8.7) | 0.691 |

| Black/African-American | |||

| No (N=45) | 32 (71.1) | 13 (28.9) | 0.097 |

| Yes (N=69) | 58 (84.1) | 11 (15.9) | |

| Duration of Incarceration | |||

| ≤180 days (N=35) | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | 0.753 |

| >180 days (N=79) | 63 (79.8) | 16 (20.3) | |

| IDU | |||

| No (N=91) | 72 (79.1) | 19 (20.9) | 1.000 |

| Yes (N=23) | 18 (78.3) | 5 (20.8) | |

| MSM | |||

| No (N=77) | 62 (80.5) | 15 (19.5) | 0.553 |

| Yes (N=37) | 28 (75.7) | 9 (24.3) | |

| At least 1 chronic disease diagnosis | |||

| No (N=66) | 51 (77.3) | 15 (22.7) | 0.607 |

| Yes (N=48) | 39 (81.3) | 9 (18.8) | |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosis | |||

| No (N=49) | 41 (83.7) | 8 (16.3) | 0.283 |

| Yes (N=65) | 49 (75.4) | 16 (24.6) | |

| At least 3 comorbid conditions | |||

| No (N=86) | 68 (79.1) | 18 (20.9) | 0.955 |

| Yes (N=28) | 22 (78.6) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Virally suppressed prior to release from prisonb | |||

| No (N=11) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.6) | 0.007 |

| Yes (N=96) | 78 (81.3) | 18 (18.8) | |

| Diagnosed with AIDSb | |||

| No (N=81) | 67 (82.7) | 14 (17.3) | 0.102 |

| Yes (N=32) | 22 (68.8) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Received HIV care prior to incarcerationb | |||

| No (N=44) | 38 (86.4) | 6 (13.6) | 0.115 |

| Yes (N=69) | 51 (73.9) | 18 (26.1) | |

| Participated in prospective research study | |||

| No (N=75) | 58 (77.3) | 17 (22.7) | 0.558 |

| Yes (N=39) | 32 (82.1) | 7 (18.0) | |

| Enrolled in Wisconsin Linkage to Care Program | |||

| No (N=71) | 55 (77.5) | 16 (22.5) | 0.618 |

| Yes (N=43) | 35 (81.4) | 8 (18.6) |

Percentages present the proportion virally suppressed / not virally suppressed with that characteristic.

Missing pre-release viral load data for 7 individuals, AIDS data for one individual and prior HIV care data for one individual.

Multiple Logistic Regression

Variables that appeared to be associated with either linkage to care or viral suppression at a significance level of 0.2 were included in the final model and include Black/African American race, prison release year (treated as a continuous variable), 3 or more comorbidities diagnosed, having an AIDS diagnosis, receiving HIV care prior to incarceration, being virally suppressed prior to release, enrollment in the WI Linkage to Care Program, and participation in the prospective research study. After adjusting for these variables (Table IV), enrollment in the WI Linkage to Care Program remained the strongest predictor of linkage to care after release from prison. Individuals who enrolled in the WI Linkage to Care Program, on average, had 3.7 times greater odds of linkage to care than non-participants when all other variables are held constant (aOR 3.7; 95% C.I. 1.2-11.0). Although not statistically significant, individuals who were virally suppressed prior to release from prison were 2.7 times more likely to achieve linkage to care (aOR 2.7; 95% C.I. 0.9-7.6).

Table IV.

Adjusted odds ratios of being linked to care after release from prison

| Adjusted ORa | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black/African American vs non-Black/African American | 1.186 | 0.520 | 2.705 | 0.685 |

| At least 3 disease diagnoses vs less than 3 | 0.674 | 0.263 | 1.723 | 0.410 |

| Diagnosed with AIDS vs no AIDS diagnosis | 0.657 | 0.279 | 1.548 | 0.337 |

| Engaged in pre-incarceration HIV care vs not | 0.904 | 0.398 | 2.049 | 0.808 |

| Enrolled in WI Linkage to Care Program vs not | 3.689 | 1.241 | 10.959 | 0.019 |

| Prison release year (continuous, 2011-2015) | 1.063 | 0.747 | 1.512 | 0.735 |

| Virally suppressed prior to release from prison vs not | 2.677 | 0.940 | 7.627 | 0.065 |

| Participated in prospective research study vs not | 0.762 | 0.240 | 2.421 | 0.645 |

Adjusted for Black/African American race, 3 or more comorbidities diagnosed, having an AIDS diagnosis, receiving HIV care prior to incarceration, prison release year, pre-release viral suppression, enrollment in the WI Linkage to Care Program, and participation in the prospective research study.

Time to Linkage to Care

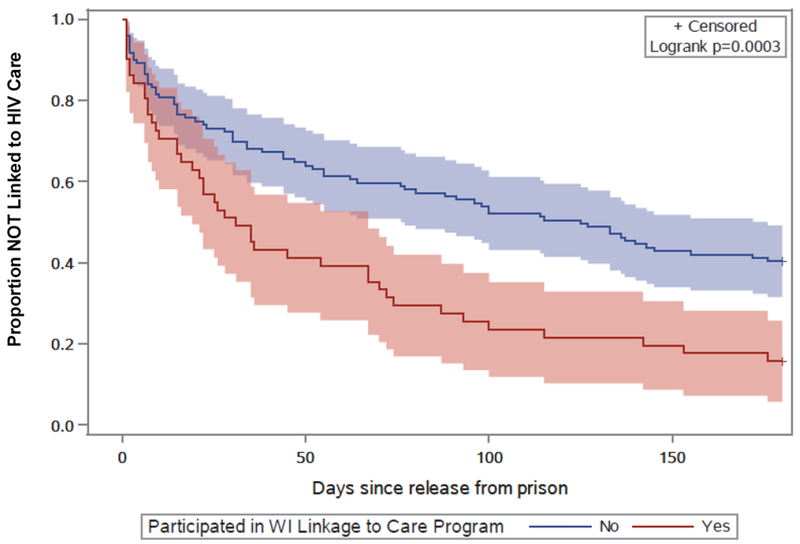

Sixty-one (36%) individuals had been linked to care by 30 days post-release, 89 (52%) individuals were linked to care by 90 days, 99 (58%) individuals were linked to care by 120 days, and 114 (67%) individuals were linked to care by 180 days. Among the 114 individuals who were linked to care within 180 days, the median time to linkage was 28 days (IQR: 7-77 days). As shown in Figure 1, individuals who participated in the WI Linkage to Care Program established HIV care significantly earlier than those who did not participate in the program (P=0.0003; logrank test). The median time to linkage among the 43 individuals who were linked to care and in the WI Linkage to Care Program was 22 days (IQR: 7-67 days), compared to a median of 30 days (IQR: 7-96 days) among the 71 individuals who were linked to care but did not participate in the program.

Figure 1:

Time to linkage to HIV care, by participation in the WI Linkage to Care Program, with 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

The goal of this study was to build a better understanding of the HIV care experiences and outcomes among a cohort of criminal justice-involved adults living with HIV as they transition from prison to community life. We found that out of the 170 individuals with HIV who released from prison, 114 (67%) were linked to care within 180 of release and 90 (53%) were virally suppressed. Estimated rates of engagement in HIV care after release from incarceration have varied substantially in the literature. A systematic review [24] identifying 12 studies that reported on engagement in HIV care after release from incarceration found that the proportion linked to care in 3 months (90 days) ranged from 28%-60% and the proportion linked to care in 6 months (180 days) ranged from 58%-85%. Our estimates of 52% and 67% at 90 and 180 days, respectively, fall within these ranges. The low proportion (36%) of individuals in this study linked to care within 30 days of release demonstrates the need for interventions that improve the timeliness of linkage and prevent lapses in medication adherence. To better understand lapses in HIV treatment following release from prison, future studies are needed that measure the number of doses individuals leave prison with, and how promptly prescriptions are refilled.

Linkage to care upon release from prison was significantly greater for individuals who participated in the WI Linkage to Care Program. Involvement in this program was observed to also positively influence how quickly HIV-positive individuals linked to care after release. Because individuals were not randomized to the WI Linkage to Care Program, the outcome (linkage to care) may reflect predisposing interest in being linked to care versus disinterest in immediately addressing one’s personal health following release. However, during the first three years the WI Linkage to Care Program was offered, only two individuals who released from prison and were offered the program refused to participate (data provided by UWCCC Inmate Social Worker). This suggests willingness to accept such services even among those who may not choose to prioritize their health during the reentry period. Thus, while this study was not designed to formally evaluate the effectiveness of the Linkage to Care Program, the findings support the potential benefits of individualized, patient-centered care coordination strategies in the context of HIV care during re-entry.

While not statistically significant, our findings also suggest that individuals with co-morbid medical and mental health conditions may have poorer continuity of HIV care after release from prison. Participants with at three or more comorbid diagnoses appeared to be less likely to be engaged in HIV care compared with those with fewer than three diagnoses. Individuals with at least one mental health diagnosis also appeared less likely to achieve viral suppression compared to individuals without any mental health conditions. Inferior HIV outcomes among individuals with comorbid conditions have been reported in previous studies [25–27] and suggest more aggressive and comprehensive clinical management is needed for persons suffering from HIV and other psychiatric and chronic comorbidities.

Research has shown that incarcerated populations are more likely to experience periods of homelessness [28], and those who are homeless or living in marginal conditions are more likely to be infected with HIV and less likely to access HIV medical care and treatment [29–31]. We were unable to ascertain the housing status of our study population through the data sources used in this study. Controlling for homelessness in the multivariable analysis could have either mitigated or exacerbated some of the effect that enrollment in the WI Linkage to Care Program had on linkage to care after release from prison. Future studies should examine the role housing status plays in these causal relationships.

This study is subject to additional limitations. Although researchers frequently use HIV viral load surveillance data to assess medical care engagement [32, 33], receipt of a viral load test is an imperfect construct for linkage to HIV care. This operationalization assumes that a viral load test was conducted at each HIV-related care appointment and that each viral load test conducted was during an outpatient appointment with an HIV or primary care provider. This method may not reflect HIV care visits among former WI DOC individuals who move out of state upon community re-entry. Likewise, viral suppression is an imperfect way to measure medication adherence, as individuals respond at different rates when lapses in medication occur. When ART is stopped completely, however, HIV RNA rebounds within days [34]. Lastly, this study has a relatively small sample size, precluding meaningful subgroup analyses and limiting our ability to test hypothesized relationships among variables with precision. The generalizability of the study’s findings to other geographic areas may be further limited because of the heterogeneous nature of correctional health care systems and the complex social determinants influencing HIV treatment outcomes.

Strengths of this study design include the incorporation of multiple data sources and the high proportion of eligible individuals contributing data through chart-reviews and administrative data analysis. Furthermore, since all PLWH in WI DOC prisons receive care in a single health system prior to release, the cohort followed in this study reflects the post-incarceration HIV care experience of all patients in the state.

This study supports the need for care coordination strategies that account for numerous types of barriers and challenges faced by PLWH during the post-incarceration period. Findings from this study add to the existing literature describing complex challenges to retention in HIV care after release from prison, and support further development of patient-centered interventions aimed at reducing barriers to care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA032306). KRH receives support from the Lifespan/Brown Criminal Justice Research Program on Substance Use, HIV, and Comorbidities, funded by the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R25DA037190). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: Participant data was collected for this study under a waiver of informed consent.

References

- 1.Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. The Lancet, 2016. 388(10049): p. 1089–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altice FL, Azbel L, Stone J, et al. The perfect storm: incarceration and the high-risk environment perpetuating transmission of HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The Lancet, 2016. 388(10050): p. 1228–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2001-2010. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Report No: NCJ 238877. Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp10.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2018 Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springer SA, Friedland GH, Doros G, Pesanti E, Altice FL. Antiretroviral treatment regimen outcomes among HIV-infected prisoners. HIV Clin Trials, 2007. 8(4): p. 205–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of human immunodeficiency virus treatment during incarceration: viral suppression at the prison gate. JAMA Intern Med, 2014. 174(5): p. 721–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westergaard RP, Kirk GD, Richesson DR, Galai N, Mehta SH. Incarceration predicts virologic failure for HIV-infected injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis, 2011. 53(7): p. 725–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA, 2009. 301(8): p. 848–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, et al. Dose-response Effect of Incarceration Events on Nonadherence to HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Among Injection Drug Users. J Infect Dis, 2011. 203(9): p. 1215–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Springer SA, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL. HIV in people reincarcerated in Connecticut prisons and jails: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV, 2014. 1(2): p. e77–e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Ragland K, et al. Treatment interruptions predict resistance in HIV-positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS, 2007. 21(8): p. 965–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNAIDS, 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanigan TP. Jails: the new frontier. HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care after release. AIDS Behav, 2013. 17 Suppl 2: p. S83–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyrer CA, Kamarulzaman A, McKee M. Prisoners, prisons, and HIV: time for reform. Lancet, 2016. 388(10049): p. 1033–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Small W, Wood E, Betteridge G, Montaner J, Kerr T. The impact of incarceration upon adherence to HIV treatment among HIV-positive injection drug users: a qualitative study. AIDS Care, 2009. 21(6): p. 708–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkley-Rubinstein L Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health & Justice, 2013. 1(1): p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisconsin Department of Health Services, D.o.P.H.A.H.P., Wisconsin HIV Surveillance Annual Review. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisconsin Department of Health Services, D.o.P.H., AIDS/HIV Program,. Linkage to Care Specialist Program Manual: A Patient Navigation Program for People Living with HIV and AIDS. 2015; Available from: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p01089.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawasarat JQ, Lois M, Wisconsin’s Mass Incarceration of African American Males, Summary. ETI Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Publi Health AIDS/HIV Program. Wisconsin HIV: Integrated Epidemiology Profile 2010-2014. Available at: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p01294.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization; Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/en/ Accessed December 27, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schumann CL, Westergaard RP, Meier AE, Ruetten ML, Vergeront JM. Developing a Patient Navigation Program to Improve Engagement in HIV Medical Care and Viral Suppression: A Demonstration Project Protocol. AIDS Behav, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1727-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun S, Crooks N, Kemnitz R, Westergaard RP. Re-entry experiences of Black men living with HIV/AIDS after release from prison: Intersectionality and implications for care. Soc Sci Med, 2018. 211: p. 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemnitz R, Kuehl TC, Hochstatter KR. Manifestations of HIV stigma and their impact on retention in care for people transitioning from prisons to communities. Health & justice, 2017. 5(1): p. 7–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iroh PA, Mayo H, and Nijhawan AE. The HIV Care Cascade Before, During, and After Incarceration: A Systematic Review and Data Synthesis. Am J Public Health, 2015. 105(7): p. e5–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu C, Umanski G, Blank A, Meissner P, Grossberg R, Selwyn PA. Comorbidity-Related Treatment Outcomes among HIV-Infected Adults in the Bronx, NY. J Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 2011. 88(3): p. 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK, et al. Co-Morbidities in Persons Infected with HIV: Increased Burden with Older Age and Negative Effects on Health-Related Quality of Life. AIDS Patient Care STDs, 2013. 27(1): p. 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2011. 58(2): p. 181–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Homelessness in the state and federal prison population. Crim Behav Ment Health, 2008. 18(2): p. 88–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerker BD, Bainbridge J, Kennedy J, et al. A population-based assessment of the health of homeless families in New York City, 2001-2003. Am J Public Health, 2011. 101(3): p. 546–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson MJ, Clark RA, Charlebois ED, et al. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. Am J Public Health, 2004. 94(7): p. 1207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milloy MJ, Marshall BD, Montaner J, Wood E. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 2012. 9(4): p. 364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montague BT, John B, Sammartino C, et al. Use of viral load surveillance data to assess linkage to care for persons with HIV released from corrections. PLOS ONE, 2018. 13(2): p. e0192074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hochstatter KR, Hull SJ, Stockman LJ, et al. Using database linkages to monitor the continuum of care for hepatitis C virus among syringe exchange clients: Experience from a pilot intervention. Int J Drug Policy, 2017. 42: p. 22–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrigan PR, Whaley M, Montaner JS. Rate of HIV-1 RNA rebound upon stopping antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 1999. 13(8): p. F59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]