Abstract

The present study analyzed the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in the transport and metabolism of methotrexate (MTX) (RFC1, ABCC1, ABCB1, GGH, FPGS, ATIC, TS, MTHFR, MTRR, MS and MTHFD1) in patients with acute leukemia (AL). The expression levels of the examined genes were analyzed by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) in patients with AL (ALL:50/AML:19) and 66 healthy individuals. The mRNA expression levels of RFC1, MS, MTRR, MTHFR and ABCB1 were decreased (P<0.05), while those of GGH, FPGS, TS and MTHFD1 (P<0.05) were overexpressed in patients with AL. Patients with high mRNA levels of GGH (OR=4.28, 95% CI=1.29–14.14), TS (OR=7.14, 95% CI 1.84–27.81), MTHFR (OR=4.81, 95% CI=1.31–17.64), ABCB1 (OR=4.61, 95% CI=1.33–15.97) and ABCC1 (OR=5.50, 95% CI=1.12–27.06) had a higher chance of relapse. Interestingly, high mRNA levels of RFC1 are a protective factor in the risk of AL relapse (OR=0.22, 95% 0.06–0.80). The results of the present study indicated that deregulation of folate pathway gene expression is associated with poor prognosis in AL and that the expression levels of these markers could serve as novel molecular targets for the treatment of patients with AL.

Keywords: acute leukemia, folate, methotrexate, resistance to methotrexate, relapse

Introduction

Leukemia is the most common childhood cancer. Mexico has one of the highest incidences of childhood leukemia in the world and has significantly higher mortality rates for this disease than do other developed nations (1). Moreover, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common; the second most frequent type of leukemia in childhood is acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (2,3).

Methotrexate (MTX) is currently one of the most widely prescribed drugs for the treatment of ALL (4,5). MTX is a folic acid antagonist, and its efficacy as an antineoplastic treatment is largely attributed to its high affinity for blocking the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines by inhibiting key enzymes (6).

MTX is predominantly transported to the interior of the cell by the reduced folate carrier (RFC/SLC19A1) (7); upon entry into the cell, MTX undergoes polyglutamylation [active methotrexate polyglutamate (MTXPG)], and 2 to 6 glutamate residues are added by folylpolyglutamate synthetase (FPGS) (7,8). The main targets of MTXPG are dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR-also inhibited by MTX monoglutamates), thymidylate synthase (TS), 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase (ATIC) and several enzymes involved in de novo purine synthesis (8). Alternatively, the polyglutamation process competes with deconjugation that converts MTXPG back into MTX by gamma-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) (8), which increases the efflux of MTX by the efflux transporters of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, including ABCC1 and ABCG2 (7,9,10).

Alterations in the transport and metabolism of MTX result in a decrease in its cellular accumulation, and this decrease has been associated with resistance to MTX and compromises its healing effect. MTX resistance has been attributed to downregulation of the RFC gene as well as increased levels of DHFR and TS enzymes (7,9,11,12). However, there are a limited number of studies on the function of the expression levels of genes involved in the transport and metabolism of MTX in patients with childhood acute leukemia (AL). In this study, we analyzed the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in the transport and metabolism of MTX [reduced folate carrier (RFC1), ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 1 (ABCC1), ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1), gamma-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH), folylpolyglutamate synthetase (FPGS), 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase (ATIC), thymidylate synthase (TS), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), methionine transferase reductase (MTRR), methionine synthase (MS) and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (MTHFD1)] in patients with AL; additionally, weanalyzed whether the expression levels of these mRNAs could be used as prognostic markers in AL.

Materials and methods

Study population

A case-control study was carried out in the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine, School of Chemical Biological Sciences, Autonomous University of Guerrero (Chilpancingo, Guerrero, México). Cases included 70 patients diagnosed with AL [ALL: 50 and AML:19] who attended the Pediatric Oncology Service of the State Cancer Institute ‘Dr. Arturo Beltran Ortega’ in the city of Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico, between August 2005 and August 2011. Diagnoses were obtained through bone marrow aspirate based on the combination of clinical features, French-American-British morphological criteria, cytochemical staining properties, molecular genetic features and immunophenotyping of blast cells, and patients were treated with the multiagent chemotherapeutic protocols used in the Cancer Institute from Guerrero State and previously reported by Gómez-Gómez et al (13) and Organista-Nava J et al (14). Controls included 66 healthy individuals (4–10×103 leukocytes/mm3) without a family history of leukemia. In the present study, subjects in both groups, including both genders, were 1–18 years of age and were residents of the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals or their guardians after a detailed briefing of the study aims. The present study and informed consent procedure were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Institute of the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Overall survival (OS) and risk classification were defined according to previous reports (13,14). Briefly, OS time was determined as the time between the day of registration into the study and the day of mortality (from any cause) or the day of last known contact. Relapse or lack of response was defined as recurrence of lymphoblasts of >20% blast cells in the marrow or localized leukemic infiltrates at any site (15). Patients with AL were classified into one of the following two groups: Low-risk, aged between 1 and 10 years with <50,000 leucocytes/mm3 at diagnosis; and High-risk, aged <1 and >10 years with >50,000 leucocytes/mm3 at diagnosis (13).

Specimen collection and total RNA extraction

Bone marrow and/or blood samples were taken from the 135 participants and placed in tubes with an anticoagulant (EDTA). Leukocytes were purified by selective osmotic lysis. Briefly, 1 ml of whole blood or 250 l of bone marrow was added to 4 ml of Red Blood Cell (RBC) Lysis Solution (155 mM ammonium chloride, 10 mM potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). The sample was mixed and incubated for 15 min on ice and was mixed every 5 min by pipetting; the samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 2,000 rpm to 4°C to remove the RBC lysis buffer. Total RNA from leukocytes was extracted according to Chomczynski and Sacchi (16).

cDNA synthesis

Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA by priming with oligo (dT). cDNA synthesis was performed by a SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for RT-PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions. The temperature cycles were as follows: 65°C for 10 min, 22°C for 10 min, 42°C for 90 min and 75°C for 5 min. cDNA was stored at −20°C.

Quantification of gene expression by real-time quantitative PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the protocol provided by the manufacturer. All reactions for the GGH, FPGS, ABCC1, ABCB1, ATIC, TS, MTRR, MS, RFC1, MTHFD1 and MTHFR genes were performed in a CFX95 Real-Time System (BIO RAD, Foster City, CΑ, USA).

The 25 µl reaction volume consisted of 12.5 µl of SYBR Green Master Mix (SYBR Green PCR reagent kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) containing Taq DNA polymerase, reaction buffer, dNTP mix, 1 mM MgCl2 (final concentration), and SYBR Green I dye, as well as 10 mM of each primer, 500 ng of the template and ultrapure water. All primer sequences and product sizes are described in Table I. PCRs were processed through 40 cycles of a 3-step PCR, including 15 sec of denaturation at 95°C, a 60-sec primer-dependent annealing phase [60 or 61°C, and according to previous reports (17–27), Table I], and 60 sec of template-dependent elongation at 72°C.

Table I.

PCR primers sequence used in this work.

| Gene symbol | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Author (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFC1 | CCTCGTGTGCTACCTTTGCTT | TGATCTCGTTCGTGACCTGCT | 125 | Abdel-Haleem et al, (17) |

| GGH | AACCTCTGACTGCCAATTTCCATAA | TCTCTGGATGCCACTGGACAC | 177 | Obata et al, (18) |

| FPGS | GGCTGGAGGAGACCAAGGATGGA | CATGAGTGTCAGGAAGC | 68 | Ogawa et al, (19) |

| TS | GCAAAGAGTGATTGACACCATCAA | CAGAGGAAGATCTCTTGGATTCCAA | 85 | Seitz et al, (20) |

| ATIC | TCTGATGCCTTCTTCCCTTT | AGGTTCGTATGAGCGAGGAT | 149 | Malek et al, (21) |

| MTHFR | GGCCATCTGCACAAAGCTAAG | AACTCACTTCGGATGTGCTTCAC | 140 | Liu et al, (22) |

| MTHFD1 | CGTGGGCAGCGGACTAA | CCTTATTTGCGCGGAGATCT | 76 | Kawakami et al, (23) |

| MTRR | GCCCGGCATTTCTATGACAC | GCCAGAGTCCAGCAATCCAC | 85 | Zhao et al, (24) |

| MS | TAAGATTTGCAAAGGTTGGGTCTGA | CTGGACATACAGGTGGGAGTTGG | 172 | Huang et al, (25) |

| ABCB1 | GCTCAGACAGGATGTGAGTTGG | ATAGCCCCTTTAACTTGAGCAGC | 99 | Yoshida et al, (26) |

| ABCC1 | TACCTCCTGTGGCTGAATCTGG | CCGATTGTCTTTGCTCTTCATG | 138 | Yoshida et al, (26) |

| HPRT | AAGCTTGCTGGTGAAAAGG | AAACATGATTCAAATCCCTGA | 134 | Ramos-Nino et al, (27) |

The expression levels of mRNAs were determined from the threshold cycle (Ct), and the relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method (28). For mRNA quantification, Ct values were normalized to the expression level of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) mRNA.

Detection of translocations

The detection of BCR-ABL, ETV6 RUNX1, AML1-ETO and CBFΒ-MYH11 translocations was realized according to the report by Organista-Nava et al (14).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) or the medians and 25 and 75th interquartiles. Categorical data were compared by Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. The Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison of the differences in mRNA expression levels between the groups. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of all data were performed using SPSS software, v.20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism software (v.5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Population characteristics

From August 2005 to August 2011, 69 patients with AL were included in this study; the mean age was 7.8±4.8 (mean ± SD) years, and the median leukocyte count at diagnosis was 15,000 leukocytes/mm3. At the time of analysis, 51 patients (73.9%) had died, and only 18 patients remained alive (26.1%). Healthy individuals had a mean age of 9.6±5.2 years and a normal leukocyte count (4–10×103 leukocytes/mm3; median 8,000 leukocytes/mm3). The characteristics of all participants are outlined in Table II. Of the 69 cases with AL examined by immunophenotype, the B lineage was the most frequent (66.7%), followed by the myeloid lineage (27.5%; Table II).

Table II.

General characteristics and clinicals of the individuals.

| Variables | AL 69 (100) | Controls 66 (100) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 7.8±4.8 | 9.6±5.2 | 0.019 |

| No. of leukocytes/mm3 at diagnosis | 15,000 (5,300–53,550) | 8,000 (7,000–10,000) | 0.005 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 27 (39.1) | 27 (40.9) | 0.727 |

| Male | 42 (60.87) | 39 (59.1) | |

| Status of individuals | |||

| Alive | 18 (26.1) | 66 (100) | |

| Deceased | 51 (73.9) | – | |

| Type of acute leukemia | |||

| Lymphoblastic | 50 (72.5) | – | |

| Myeloblastic | 19 (27.5) | – | |

| Risk by age and leukocytes at diagnosis | |||

| Low-risk | 27 (39.1) | – | |

| High-risk | 42 (60.9) | – | |

| Relapse | |||

| No | 18 (26.1) | – | |

| Yes | 51 (73.9) | – | |

| Inmunophenotype | |||

| B-lineage | 46 (66.7) | – | |

| T-lineage | 1 (1.5) | – | |

| B/T-lineage | 3 (4.3) | – | |

| Myeloid-lineage | 19 (27.5) | – | |

| Chromosomal translocation | |||

| BCR-ABL [t(9;22)] | 2 (2.9) | – | |

| ETV6-RUNX1 [t(12;21)] | 1 (1.5) | ||

| AML1-ETO [t(8;21)] | 2 (2.9) | ||

| None | 57 (82.6) | – | |

| Not determined | 7 (10.1) | – |

Gene expression

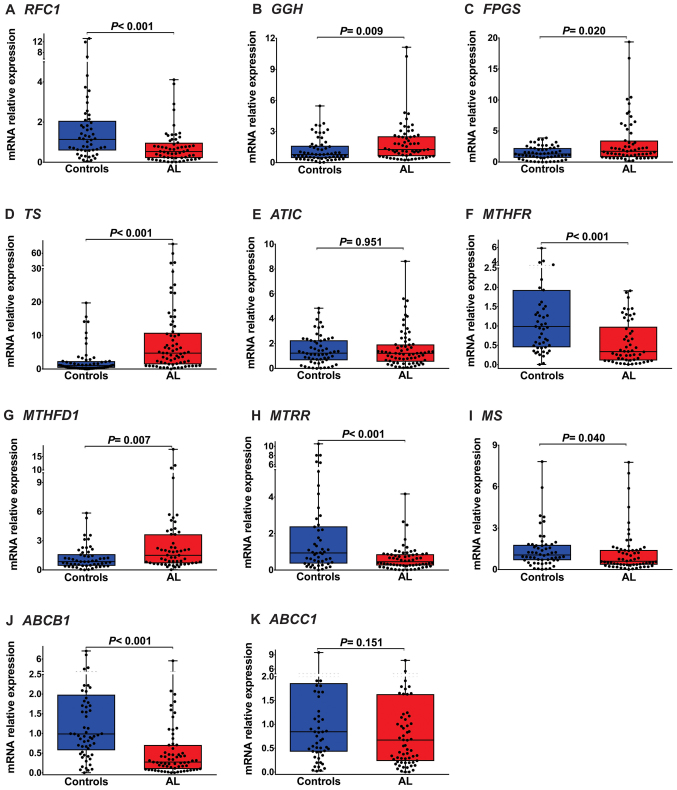

Using RT-qPCR assays, we examined the expression of levels genes involved in the transport and metabolism of MTX (RFC1, ABCC1, ABCB1, ABCC2, ABCG2, GGH, FPGS, ATIC, TS, MTHFR, MTRR, MS and MTHFD1) in patients with AL and healthy individuals. The expression levels of RFC1 (median: 0.53, P<0.001; Fig. 1A and Table III), MTHFR (median: 0.33, P<0.001; Fig. 1F and Table III), MTRR (median: 0.46, P<0.001; Fig. 1H and Table III), MS (median: 0.60, P=0.040; Fig. 1I and Table III) and ABCB1 (median: 0.27, P<0.001; Fig. 1J and Table III) in patients with AL were significantly lower than in healthy individuals. GGH (median: 1.26, P=0.009, Fig. 1B and Table III), FPGS (median: 1.74, P=0.02; Fig. 1C and Table III), TS (median: 4.75, P<0.001; Fig. 1D and Table III) and MTHFD1 (median: 1.51, P=0.007; Fig. 1G and Table III) were highly expressed in the AL group. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table III, we did not observe changes in ATIC (P=0.951; Fig. 1E and Table III) and ABCC1 (P=0.151; Fig. 1K and Table III) expression levels between patients with AL and healthy individuals.

Figure 1.

Folate pathway gene expression in childhood AL. (A) RFC1 mRNA expression was significantly lower in patients with AL than in healthy individuals [median (25–75 percentiles), 0.53 (0.21–0.97); P<0.001]. (B) GGH mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with AL [1.26 (0.62–2.54); P=0.0009]. (C) FPGS expression in patients with AL was significantly higher than that in healthy individuals [1.74 (0.80–3.46); P=0.020]. (D) TS mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with AL [4.75 (1.40–10.83); P<0.001]. (E) ATIC mRNA levels were not significantly different between patients with AL and healthy individuals [1.22 (0.54–1.93); P=0.951]. (F) MTHFR mRNA expression was significantly lower in patients with AL than in healthy individuals [0.33 (0.11–0.98); P<0.001]. (G) MTHFD1 mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with AL [1.51 (0.68–3.66); P=0.007]. (H, I and J) MTRR, MS and ABCB1 mRNA levels were significantly diminished in patients with AL [0.46 (0.25–0.87); P<0.001, 0.60 (0.35–1.41); P=0.040 and 0.27 (0.09–0.71); P<0.001, respectively]. (K) ABCC1 mRNA expression was not significantly different between patients with AL and healthy individuals [0.67 (0.23–1.63); P=0.151]. RFC1, reduced folate carrier; GGH, γ-glutamyl hydrolase; FPGS, folylpolyglutamate synthetase; TS, thymidylate synthase; ATIC, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTHFD1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTRR, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; MS, methionine synthase; ABCB1, ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1; ABCC1, ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 1; AL, acute leukemia.

Table III.

Folate pathway gene expression in childhood AL and healthy individuals.

| Median | 25-75% Percentiles | P-valueφ | Mean | Sth. deviation | Sth. error of mean | 95% CI of mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFC1 | Controls | 1.14 | 0.58–2.06 | <0.001a | 1.81 | 2.50 | 0.35 | 1.12–2.51 |

| AL | 0.53 | 0.21–0.97 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.11 | 0.54–0.98 | ||

| GGH | Controls | 0.78 | 0.44–1.62 | 0.009a | 1.23 | 1.15 | 0.15 | 0.93–1.53 |

| AL | 1.26 | 0.62–2.54 | 1.93 | 1.99 | 0.25 | 1.43–2.43 | ||

| FPGS | Controls | 1.31 | 0.68–2.26 | 0.020a | 1.46 | 1.06 | 0.14 | 1.18–1.74 |

| AL | 1.74 | 0.80–3.46 | 3.21 | 3.84 | 0.50 | 2.21–4.21 | ||

| TS | Controls | 1.02 | 0.37–2.34 | <0.001a | 2.52 | 4.23 | 0.55 | 1.42–3.62 |

| AL | 4.75 | 1.40–10–83 | 9.42 | 13.83 | 1.66 | 6.10–12.74 | ||

| ATIC | Controls | 1.23 | 0.65–2.26 | 0.951 | 1.45 | 1.18 | 0.15 | 1.18–1.80 |

| AL | 1.22 | 0.54–1.93 | 1.60 | 1.56 | 0.19 | 1.23–1.98 | ||

| MTHFR | Controls | 0.99 | 0.45–1.93 | <0.001a | 1.37 | 1.24 | 0.17 | 1.02–1.72 |

| AL | 0.33 | 0.11–0.98 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.41–0.71 | ||

| MTHFD1 | Controls | 0.85 | 0.43–1.62 | 0.007a | 1.27 | 1.23 | 0.17 | 0.93–1.61 |

| AL | 1.51 | 0.68–3.66 | 2.60 | 3.22 | 0.43 | 1.75–3.46 | ||

| MTRR | Controls | 0.94 | 0.36–2.39 | <0.001a | 1.90 | 2.41 | 0.34 | 1.22–2.59 |

| AL | 0.46 | 0.25–0.87 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.47–0.81 | ||

| MS | Controls | 1.05 | 0.68–1.79 | 0.040a | 1.42 | 1.40 | 0.19 | 1.05–1.80 |

| AL | 0.60 | 0.35–1.41 | 1.20 | 1.56 | 0.20 | 0.81–1.60 | ||

| ABCB1 | Controls | 0.99 | 0.57–1.98 | <0.001a | 1.53 | 1.50 | 0.19 | 1.14–1.91 |

| AL | 0.27 | 0.09–0.71 | 0.62 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.40–0.85 | ||

| ABCC1 | Controls | 0.84 | 0.43–1.86 | 0.151 | 1.26 | 1.43 | 0.19 | 0.88–1.64 |

| AL | 0.67 | 0.23–1.63 | 1.10 | 1.36 | 0.17 | 0.75–1.42 |

Obtained by Mann Whitney test

Significant P<0.05; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval.

Gene expression in patients with AL with/without relapse

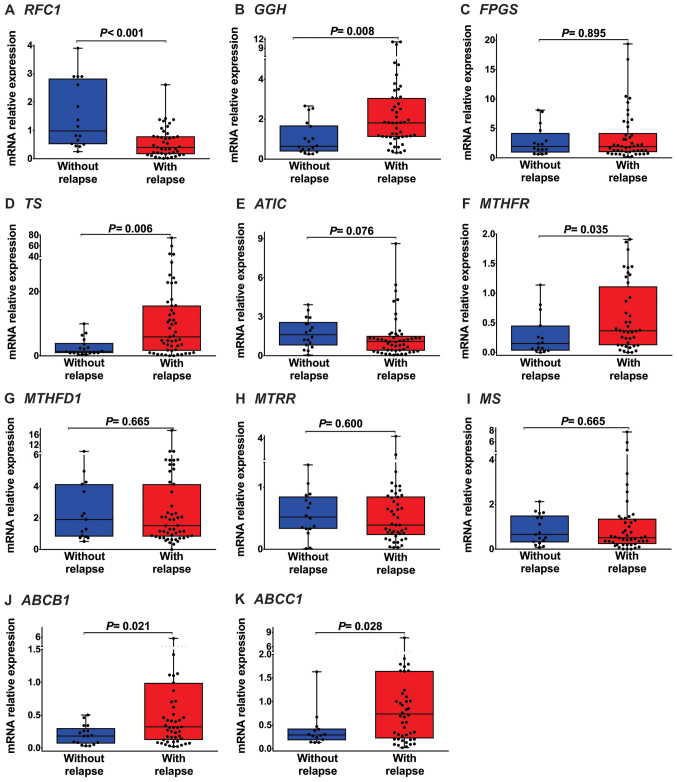

Cases were divided into the following subtype groups: With relapse (51 cases of AL) and without relapse (18 cases of AL). The expression levels of RFC1 (median: 0.40, P<0.001; Fig. 2A and Table IV), were significantly lower in AL patients with relapse than in AL patients without relapse.

Figure 2.

Folate pathway gene expression in patients with AL with and without relapse. (A) RFC1 mRNA expression was significantly lower in patients with AL with relapse than in those without relapse [median (25–75 percentiles), 0.40 (0.16–0.79); P<0.001]. (B) GGH mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with AL with relapse [1.81 (1.12–3.06); P=0.008]. (C) FPGS mRNA expression was not significantly different between patients with AL with and without relapse [1.89 (0.97–4.20); P=0.895]. (D) TS mRNA expression were significantly increased in patients with AL with relapse [5.89 (1.58–15.66); P=0.006]. (E) ATIC mRNA expression was not significantly different between patients with AL with and without relapse [1.09 (0.38–1.52); P=0.076]. (F) MTHFR mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with AL with relapse [0.37 (0.12–1.12); P=0.035]. (G, H and I) MTHFD1, MTRR and MS mRNA expression levels were not significantly different between patients with AL with and without relapse [1.51 (0.82–4.40); P=0.665, 0.40 (0.23–0.86); P=0.600 and 0.51 (0.23–1.36); P=0.665, respectively]. (J and K) ABCB1 and ABCC1 mRNA expression levels were significantly increased in patients with AL with relapse [0.32 (0.12–0.99); P=0.021, 0.76 (0.22–1.65); P=0.028, respectively]. RFC1, reduced folate carrier; GGH, γ-glutamyl hydrolase; FPGS, folylpolyglutamate synthetase; TS, thymidylate synthase; ATIC, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTHFD1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTRR, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; MS, methionine synthase; ABCB1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1; ABCC1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 1; AL, acute leukemia.

Table IV.

Folate pathway gene expression in patients with AL with and without relapse.

| Median | 25-75% Percentiles | P-valueφ | Mean | Sth. Deviation | Sth. error of mean | 95% CI of mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFC1 | Without relapse | 0.98 | 0.51–2.83 | <0.001a | 1.50 | 1.17 | 0.29 | 0.87–2.12 |

| With relapse | 0.40 | 0.16–0.79 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.41–0.74 | ||

| GGH | Without relapse | 0.64 | 0.38–1.68 | 0.008a | 1.03 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.61–1.44 |

| With relapse | 1.81 | 1.12–3.06 | 2.45 | 2.46 | 0.23 | 1.72–3.14 | ||

| FPGS | Without relapse | 1.94 | 0.92–4.22 | 0.895 | 2.81 | 2.49 | 0.62 | 1.49–4.14 |

| With relapse | 1.89 | 0.97–4.20 | 3.45 | 4.17 | 0.61 | 2.25–4.72 | ||

| TS | Without relapse | 1.40 | 0.88–4.00 | 0.006a | 2.66 | 2.74 | 0.65 | 1.30–4.03 |

| With relapse | 5.89 | 1.58–15.66 | 11.97 | 15.53 | 2.17 | 7.61–16.34 | ||

| ATIC | Without relapse | 1.61 | 0.79–2.59 | 0.076 | 1.74 | 1.13 | 0.27 | 1.18–2.30 |

| With relapse | 1.09 | 0.38–1.52 | 1.40 | 1.61 | 0.23 | 0.94–1.85 | ||

| MTHFR | Without relapse | 0.15 | 0.03–0.45 | 0.035a | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.09–0.47 |

| With relapse | 0.37 | 0.12–1.12 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.41–0.78 | ||

| MTHFD1 | Without relapse | 1.90 | 0.82–4.14 | 0.665 | 2.60 | 2.41 | 0.62 | 1.26–3.93 |

| With relapse | 1.51 | 0.82–4.40 | 2.69 | 3.10 | 0.43 | 1.82–3.56 | ||

| MTRR | Without relapse | 0.52 | 0.33–0.85 | 0.600 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.37–0.76 |

| With relapse | 0.40 | 0.23–0.86 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.40–0.83 | ||

| MS | Without relapse | 0.66 | 0.30–1.51 | 0.665 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.53–1.21 |

| With relapse | 0.51 | 0.23–1.36 | 1.10 | 1.55 | 0.23 | 0.65–1.56 | ||

| ABCB1 | Without relapse | 0.18 | 0.07–0.30 | 0.021a | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.12–0.27 |

| With relapse | 0.32 | 0.12–0.99 | 0.73 | 1.04 | 0.15 | 0.44–1.03 | ||

| ABCC1 | Without relapse | 0.29 | 0.18–0.42 | 0.028a | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.17–0.62 |

| With relapse | 0.76 | 0.22–1.65 | 1.01 | 1.33 | 0.19 | 0.70–1.47 |

Obtained by Mann Whitney test

Significant P<0.05; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval.

GGH (median: 1.81, P=0.008; Fig. 2B and Table IV), TS (median: 5.89, P=0.006; Fig. 2D and Table IV), MTHFR (median: 0.37, P=0.035; Fig. 2F and Table IV), ABCB1 (median: 0.32, P=0.021; Fig. 2J and Table IV) and ABCC1 (median: 0.76, P=0.028; Fig. 2K and Table IV). Were highly expressed in the AL patients with relapse. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table IV, we did not observe changes in FPGS (P=0.895; Fig. 2C and Table IV), ATIC (P=0.076; Fig. 2E and Table IV), MTHFD1 (P=0.665, Fig. 2G and Table IV), MTRR (P=0.600; Fig. 2H and Table IV) and MS (P=0.665; Fig. 2I and Table IV) expression levels between AL patients with relapse and AL patients without relapse.

Folate pathway gene expression is associated with AL relapse

To evaluate the correlation between mRNA expression and the risk of relapse to AL, patients were divided into low expression and high expression groups. The media expression levels of RFC1 (0.76-fold), GGH (1.93-fold), FPGS (3.21-fold), TS (9.42-fold), ATIC (1.60-fold), MTHFR (0.56-fold), MTHFD1 (2.60-fold), MTRR (0.64-fold), MS (1.20-fold), ABCB1 (0.62-fold) and ABCC1 (1.10-fold) were used as cut-off points to divide patients with AL into two groups (Table III). Patients with expression lower than the cut-off value were considered to be in the low expression group [RFC1 (n=31), GGH (n=30), FPGS (n=31), TS (n=36), ATIC (n=35), MTHFR (n=27), MTHFD1 (n=30), MTRR (n=34), MS (n=35), ABCB1 (n=36) and ABCC1 (n=39)], while patients with expression higher than the cut-off value were considered to be in the high expression group [RFC1 (n=30), GGH (n=33), FPGS (n=32), TS (n=33), ATIC (n=34), MTHFR (n=32), MTHFD1 (n=30), MTRR (n=30), MS (n=29), ABCB1 (n=33) and ABCC1 (n=24)].

Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the correlation between the mRNA expression levels of genes in the folate pathway and the risk of AL relapse. In this analysis, an association was observed between the mRNA expression levels of RFC1, GGH, TS, MTHFR, ABCB1 and ABCC1 and the risk of relapse in patients with AL (P<0.05). Compared with patients with AL and low mRNA expression, patients with AL and high mRNA expression had a significant increase in the risk of relapse (GGH: OR=4.28, CI95% 1.29–14.14, P=0.017; TS: OR=7.14, CI95% 1.84–27.81, P=0.005; MTHFR: OR=4.81, CI95% 1.31–17.64, P=0.018; ABCB1: OR=4.61, CI95% 1.33–15.97, P=0.016 and ABCC1: OR=5.50, CI95% 1.12–27.06; P=0.036; Table V). In contrast, high mRNA levels of RFC1 had a protective effect (OR=0.22; CI95% 0.06–0.80; P=0.021).

Table V.

Association of folate pathway gene expression and clinical features with the risk of relapse to AL.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (n) | Without relapse n (%) | With relapse n (%) | P-valuea | OR | CI 95% | P-valueb | OR | CI 95% | P-valuec |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 9 | 18 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male | 9 | 33 | 0.400 | 1.83 | 0.62–5.44 | 0.275 | |||

| Risk by age and leukocytes at diagnosis | |||||||||

| Low-risk | 11 | 15 | 1.00 | ||||||

| High-risk | 7 | 36 | 0.024d | 3.77 | 1.23–11.59 | 0.020d | |||

| Immunophenotype | |||||||||

| Lymphoid-lineage | 14 | 36 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Myeloid-lineage | 4 | 15 | 0.761 | 1.14 | 0.41–5.16 | 0.549 | |||

| RFC1 (61) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 4 (25.0) | 27 (60.0) | 0.021d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 12 (75.0) | 18 (40.0) | 0.22 | 0.06–0.80 | 0.021d | 0.23 | 0.06–0.87 | 0.030d | |

| GGH (63) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 13 (72.2) | 17 (37.8) | 0.024d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 5 (27.8) | 28 (62.2) | 4.28 | 1.29–14.14 | 0.017d | 6.53 | 1.65–25.83 | 0.008d | |

| FPGS (63) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 8 (50.0) | 23 (48.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 8 (50.0) | 24 (51.1) | 1.04 | 0.34–3.25 | 0.941 | ||||

| TS (69) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 15 (83.3) | 21 (41.2) | 0.002d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 3 (16.7 | 30 (58.8) | 7.14 | 1.84–27.81 | 0.005d | 7.40 | 1.81–30.33 | 0.005d | |

| ATIC (69) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 6 (33.3) | 29 (56.9) | 0.106 | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 12 (66.7) | 22 (43.1) | 0.38 | 0.12–1.17 | 0.086 | ||||

| MTHFR (59) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 11 (73.3) | 16 (49.1) | 0.037d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 4 (26.7) | 28 (50.9) | 4.81 | 1.31–17.64 | 0.018d | 4.50 | 1.18–17.12 | 0.027d | |

| MTHFD1 (60) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 7 (46.7) | 23 (51.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 8 (53.3) | 22 (48.9) | 0.84 | 0.26–2.69 | 0.766 | ||||

| MTRR (64) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 7 (43.8) | 27 (56.2) | 0.405 | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 9 (56.2) | 21 (43.8) | 0.60 | 0.19–1.89 | 0.388 | ||||

| MS (64) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 8 (47.1) | 27 (57.4) | 0.573 | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 9 (52.9) | 20 (42.6) | 0.66 | 0.22–2.01 | 0.462 | ||||

| ABCB1 (69) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 14 (77.8) | 22 (43.1) | 0.014d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 4 (22.2) | 29 (56.9) | 4.61 | 1.33–15.97 | 0.016d | 5.13 | 1.38–18.98 | 0.014d | |

| ABCC1 (63) | |||||||||

| Low-levels | 13 (86.7) | 26 (54.2) | 0.033d | 1.00 | |||||

| High-levels | 2 (13.3) | 22 (45.8) | 5.50 | 1.12–27.06 | 0.036d | 4.85 | 0.95–24.74 | 0.050d | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

P-value was obtained by the Chi-square test.

P-value was obtained by univariate logistic regression analysis, taking reference to female, 1–10 years/<50,000 leukocytes/mm (low-risk), Lymphoid-lineage and Low-levels (RFC1, GGH, FPGS, TS, ATIC, MTHFR, MTHFD1, MTRR, MS, ABCB1 and ABCC1).

P-value was obtained by multivariate logistic regression analysis between relapse, risk by age and leukocytes at diagnosis and mRNA expression levels of genes involved in the transport (RFC1, ABCB1 and ABCC1) and metabolism (GGH, TS and MTHFR) of MTX.

Significant P<0.05.

The following variables were included in a multivariate analysis: Risk by age and leukocytes at diagnosis and the expression levels of RFC1, GGH, TS, MTHFR ABCB1 and ABCC1 mRNA, to determine whether the mRNA expression of each gene predicts the risk of relapse independently. It was observed that the expression levels of RFC1, GGH, TS, MTHFR ABCB1 and ABCC1 were independent prognostic factors in AL patients (Table V). These data suggest that the mRNA expression levels of folate pathway genes could play an important role in the risk of relapse in this disease.

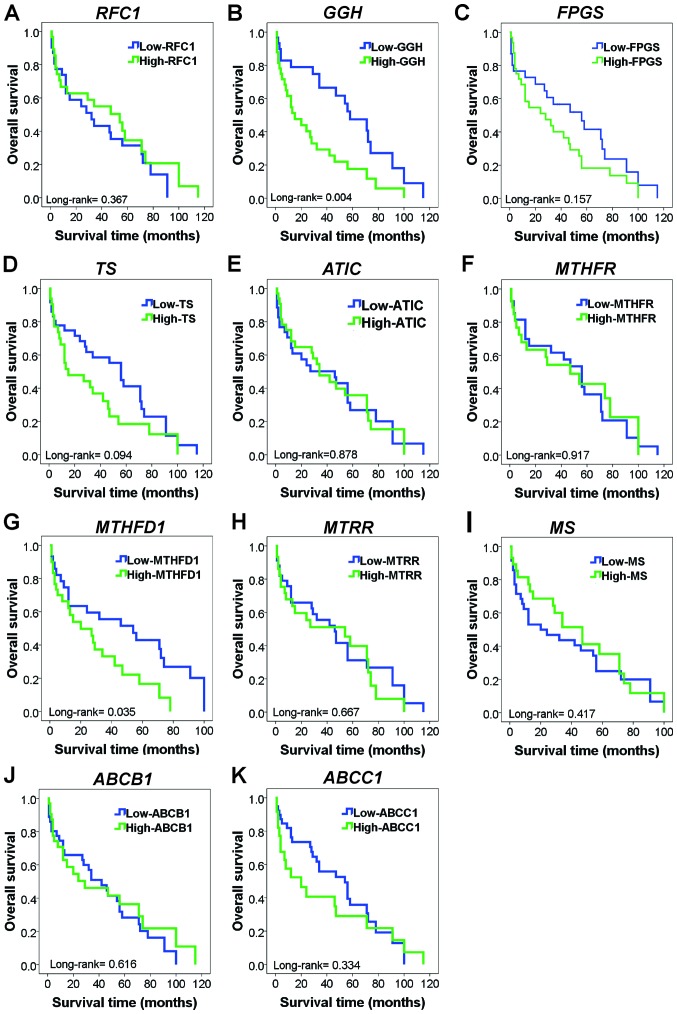

Poor survival based on the mRNA expression levels of folate pathway genes

The association between the mRNA expression levels of folate pathway genes and the survival of patients with AL was investigated. In this analysis, patients with high expression levels of GGH mRNA tended to have lower survival than did those with low expression levels of GGH mRNA (log-rank test, P=0.004; Fig. 3B). Similarly, a difference in survival was evident among individuals with high levels of MTHFD1 mRNA (log-rank test; P=0.035; Fig. 3G). In patients with AL, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed no significance between survival and the mRNA levels of RFC1, FGS, TS, ATIC, MTHFR, MTRR, MS, ABCB1, and ABCC1 (log-rank test; P>0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival showing the influence of folate pathway gene expression in patients with AL. (A) OS in patients with AL with high or low RFC1 mRNA expression (P=0.367). (B) OS in patients with AL with high or low GGH mRNA expression. Patients who exhibited high levels of GGH mRNA expression exhibited significantly decreased OS (P=0.004). (C) OS in patients with AL with high or low FPGS mRNA expression (P=0.157). (D) OS in patients with AL with high or low TS mRNA expression (P=0.094). (E) OS in patients with AL with high or low ATIC mRNA expression (P=0.878). (F) OS in patients with AL with high or low MTHFR mRNA expression (P=0.917). (G) OS in patients with AL with high or low MTHFD1 mRNA expression. Patients who exhibited high levels of MTHFD1 mRNA expression also exhibited significantly decreased OS (P=0.035). (H) OS in patients with AL with high or low MTRR mRNA expression (P=0.667). (I) OS in patients with AL with high or low MS mRNA expression (P=0.417). (J) OS in patients with AL with high or low ABCB1 mRNA expression (P=0.616). (K) OS in patients with AL with high or low ABCC1 mRNA expression (P=0.334). RFC1, reduced folate carrier; GGH, γ-glutamyl hydrolase; FPGS, folylpolyglutamate synthetase; TS, thymidylate synthase; ATIC, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTHFD1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTRR, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; MS, methionine synthase; ABCB1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1; ABCC1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 1; AL, acute leukemia; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

ALs are the most common type of childhood cancer. Despite advancements in therapeutic strategies, the prognosis of patients with AL significantly varies and is difficult to predict. Additionally, different responses to the same therapy are observed among patients with AL (29). Therefore, finding new biomarkers for the identification of patients with a high risk of not responding to treatment is very important to modify therapeutic methods to improve the survival of patients with AL.

MTX was one of the first anticancer therapeutic agents for the treatment of childhood leukemia (4,6). In this study, the expression of RFC1 was significantly lower (P=0.006) in patients with AL with relapse than in those without relapse. According to previous studies, the expression levels of RFC1 mRNA are diminished in HEP-2 cells treated with MTX, and reduced RFC1 leads to decreased intracellular MTX, which is involved in MTX resistance (30,31). Thus, the decreased expression of RFC1 mRNA results in inefficient absorption of antifolates by tumor cells, leading to the development of MTX resistance.

Alternatively, the mRNA expression levels of MTX-metabolizing enzymes, including FPGS and GGH, were elevated in patients with AL, while GGH mRNA was overexpressed in patients who relapsed during treatment with MTX. GGH is responsible for eliminating the glutamate groups from MTXPG, favoring its efflux from cells, and high levels of GGH mRNA are reportedly associated with resistance to MTX (32). Our results are consistent with those of Kim et al (33), who reported that overexpression of GGH is associated with MTX resistance. These results suggest that GGH is related to MTX resistance in patients with AL since its overexpression could favor the exit of MTX from the cell, preventing it from exerting its antineoplastic activity. Similarly, GGH expression is associated with poor prognosis and unfavorable clinical outcomes in breast and prostate cancers and pleural mesothelioma (18,34,35). Consistent with these findings, our data suggest that high mRNA levels of GGH play an important role in survival in patients with AL and that GGH may be a therapeutic target in AL. Additionally, FPGS mRNA was overexpressed in patients with AL with relapse. Similar to previous reports, the expression of FPGS was elevated in AL cell lines (36).

Regarding folate-dependent enzymes, changes were observed in the mRNA expression levels of the MS, MTRR, MTHFR, TS, MTHFD1 and ATIC genes. MTRR is involved in the synthesis of DNA and production of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM); MTRR also plays an important role in carcinogenesis (37). MTRR is an enzyme that controls the activity of MS in the metabolism of folate through the transfer of methyl groups of methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine via MS (24,37,38). No studies have analyzed the expression of MTTR mRNA in patients with AL. In our study, MTRR expression levels were lower in the AL group than in the control group. Nevertheless, significant differences were not observed between patients with and without relapse. In patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer cells, increased expression of MTRR mRNA (37,39) was observed.

MS catalyzes the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine; deficiencies in the activity of MS result in hyperhomocysteinemia (25,40), which is a risk factor for cancer (41). This decrease in MS activity leads to an increase in homocysteine and a reduction in DNA methylation processes and, is an important factor in the development of cancer (42,43). Our results show decreased levels of MS in patients with AL, similar to the findings in ovarian, renal, prostate, breast, colon, leukemia, non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines (44).

Another important enzyme involved in the remethylation of homocysteine is MTHFR, which catalyzes the conversion of 5,10-CH3-THF to 5-CH3-THF for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (22,45). In this study, MTHFR mRNA levels were decreased in patients with AL. We also observed that MTHFR mRNA levels were substantially elevated in patients who relapsed during treatment compared to those in patients who did not relapse. This observation is similar to the findings of Liu et al (22), who observed that the reduced mRNA level of MTHFR had an association with the risk for esophageal cancer. The biological effect of overexpression of MTHFR mRNA is not completely defined, and there are no studies showing its relationship with response to treatment in patients with AL.

TS is a folate-dependent enzyme that plays a central role in deoxythymidine monophosphate synthesis, which is critical for the synthesis and repair of DNA by serving as the main intracellular source of dUTM (46,47). Our results show increased levels of TS mRNA in patients with AL, similar to findings observed in breast cancer (47) and pancreatic cancer (20). We also found that patients with AL with relapse showed increased mRNA expression levels of TS. Our results are in line with previous reports showing a significant aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis (47–49). These data indicate that TS is involved in disease progression and relapse in cancer, which occur because TS is a target enzyme of MTXPG and is overexpressed in AL and in patients with relapse. It is possible that MTX does not inhibit this enzyme, as we did not observe inhibition of TS; thus, DNA synthesis is favored, and cells continue to proliferate uncontrollably.

The ABC transporter family is a group of membrane transporters that transport different molecules through the cell membrane. ABCs are divided into different subgroups (named A-G) and have been associated with multidrug resistance (26,50,51). Regarding the ABC transporter family, we found increased expression levels of ABCB1 and ABCC1 mRNAs in patients with AL who relapsed during treatment. Our findings are similar to those reported by Ho et al (52) and Eadie et al (53), who observed that the overexpression of ABC transporter mRNA (ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2) is correlated with increased cellular resistance of leukemic cells.

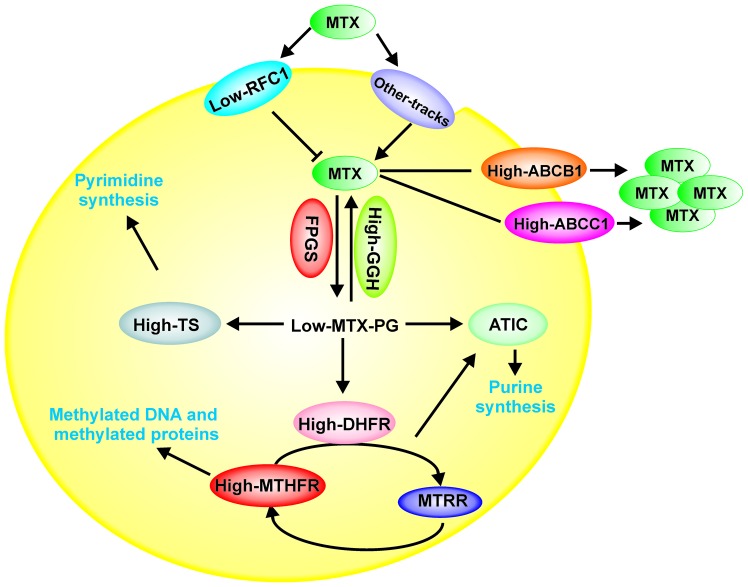

Likewise, in a multivariate analysis, we observed that the expression levels of RFC1, GGH, TS, MTHFR ABCB1 and ABCC1 are independent prognostic factors in AL patients, excluding leukocytes at diagnosis and age (Table V). As shown in Fig. 4, we hypothesize that the high expression levels of ABCB1 and ABCC1 genes play an important role in the resistance to MTX treatment by favoring its efflux from cells. Likewise, decreased levels of RFC1 mRNA will result in MTX not being captured by the cells. In additon, the increase in GGH levels favors the depolyglutamation of MTX, preventing it from exerting its activity. ATIC and TS are overexpressed, indicating that MTXPG does not inhibit these enzymes and, favors cell proliferation in AL patients with relapse (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Model of the possible role of folate pathway gene expression levels involved in the transport and metabolism of MTX in patients with AL with relapse. The decreased levels of RFC1 could favor inhibition of MTX internalization into the cell, while the increase in GGH levels favors MTX depolyglutamation, preventing MTX from exerting its activity, which also affects the levels of ATIC and TS (overexpression). Moreover, high expression levels of ABCB1 and ABCC1 cause the efflux of MTX from the cell. All of these processes favor cell proliferation and survival. RFC1, reduced folate carrier; GGH, γ-glutamyl hydrolase; FPGS, folylpolyglutamate synthetase; TS, thymidylate synthase; ATIC, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTHFD1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTRR, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase reductase; MS, methionine synthase; ABCB1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1; ABCC1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 1.

In conclusion, our data indicate that the deregulation of the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in the transport (RFC1, ABCB1, and ABCC1) and metabolism (GGH, TS, MTHFR) of MTX had impacts on the risk of relapse and survival of AL Mexican patients. However, this analysis was based only on 69 patients and needs to be confirmed in a larger population.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Jorge Organista-Nava (CVU: 236745) and Yazmín Gómez-Gómez (CVU: ٢٣٦٧٢٨) were recipients of postdoctoral fellowships from CONACYT. The present study was supported by grant from CONACYT, México (Fondo Sectorial de Investigación en Salud y Seguridad Social; grant no. A3-S-47392).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JON, YGG, BIA and MALV made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. BIA, ABRR, MVSH, MAJL, OMH and MALV provided the study materials or patients. JON, YGG, JGS and MALV collection and assembled the data. JON, YGG, JGS, ABRR, MVSH, MAJL, OMH and MALV performed the data analysis and interpretation. JON, YGG, BIA and MALV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study and informed consent procedure were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Institute of the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Patients who participated in this research had complete clinical data. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals or their guardians after a detailed briefing of the study aims.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bekker-Méndez VC, Miranda-Peralta E, Núñez-Enríquez JC, Olarte-Carrillo I, Guerra-Castillo FX, Pompa-Mera EN, Ocaña-Mondragón A, Rangel-López A, Bernáldez-Ríos R, Medina-Sanson A, et al. Prevalence of gene rearrangements in mexican children with acute lymphoblastic Leukemia: A population study-report from the mexican interinstitutional group for the identification of the causes of childhood leukemia. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:210560. doi: 10.1155/2014/210560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mejía-Aranguré JM, Pérez-Saldivar MaL, Pelayo-Camacho R, et al. Childhood acute leukemias in Hispanic population: Differences by age peak and immunophenotype. In: Rijeka, editor. Novel Aspects in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. InTech; Croatia: 2011. p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leukemia in Childers. American Cancer Society, 2019, corp-author. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/leukemia-in-children.html. [Mar 10;2019 ];

- 4.Stanulla M, Schrappe M. Treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2009;46:52–63. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hider SL, Bruce IN, Thomson W. The pharmacogenetics of methotrexate. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1520–1524. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assaraf YG. Molecular basis of antifolate resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:153–181. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Beaumais TA, Jacqz-Aigrain E. Intracellular disposition of methotrexate in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:822–834. doi: 10.2174/138920012800840400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonen N, Assaraf YG. Antifolates in cancer therapy: Structure, activity and mechanisms of drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:183–210. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojtuszkiewicz A, Peters GJ, Woerden NL, Dubbelman B, Escherich G, Schmiegelow K, Sonneveld E, Pieters R, van de Ven PM, Jansen G, et al. Methotrexate resistance in relation to treatment outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:61. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothem L, Aronheim A, Assaraf YG. Alterations in the expression of transcription factors and the reduced folate carrier as a novel mechanism of antifolate resistance in human leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8935–8941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jonge R, Hooijberg JH, van Zelst BD, Jansen G, van Zantwijk CH, Kaspers GJ, Peters GJ, Ravindranath Y, Pieters R, Lindemans J. Effect of polymorphisms in folate-related genes on in vitro methotrexate sensitivity in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:717–720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez-Gómez Y, Organista-Nava J, Saavedra-Herrera MV, Rivera-Ramírez AB, Terán-Porcayo MA, Del Carmen Alarcón-Romero L, Illades-Aguiar B, Leyva-Vázquez MA. Survival and risk of relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a Mexican population is affected by dihydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:665–672. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organista-Nava J, Gómez-Gómez Y, Illades-Aguiar B, Del Carmen Alarcón-Romero L, Saavedra-Herrera MV, Rivera-Ramírez AB, Garzón-Barrientos VH, Leyva-Vázquez MA. High miR-24 expression is associated with risk of relapse and poor survival in acute leukemia. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1639–1649. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, Hiddemann W, Sauter S, Henze G, Zimmermann M, Lampert F, Havers W, Niethammer D, et al. Chemotherapy in 998 unselected childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Results and conclusions of the multicenter trial ALL-BFM 86. Blood. 1994;84:3122–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Haleem AM, El-Zeiry MI, Mahran LG, Abou-Aisha K, Rady MH, Rohde J, Mostageer M, Spahn-Langguth H. Expression of RFC/SLC19A1 is associated with tumor type in bladder cancer patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obata T, Tanaka M, Suzuki Y, Sasaki T. The role of thymidylate synthase in pemetrexed-resistant malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. J Cancer Therapy. 2013;4:8. doi: 10.4236/jct.2013.46119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa M, Watanabe M, Mitsuyama Y, Anan T, Ohkuma M, Kobayashi T, Eto K, Yanaga K. Thymidine phosphorylase mRNA expression may be a predictor of response to post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 in patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2463–2468. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seitz U, Wagner M, Neumaier B, Wawra E, Glatting G, Leder G, Schmid RM, Reske SN. Evaluation of pyrimidine metabolising enzymes and in vitro uptake of 3′-[18F]fluoro-3′-deoxythymidine [(18F)FLT] in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1174–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malek RL, Irby RB, Guo QM, Lee K, Wong S, He M, Tsai J, Frank B, Liu ET, Quackenbush J, et al. Identification of Src transformation fingerprint in human colon cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:7256–7265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R, Yin L, Pu Y. Association between gene expression of metabolizing enzymes and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas in china. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:1211–1217. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami K, Ooyama A, Ruszkiewicz A, Jin M, Watanabe G, Moore J, Oka T, Iacopetta B, Minamoto T. Low expression of gamma-glutamyl hydrolase mRNA in primary colorectal cancer with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1555–1561. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao JY, Yang XY, Gong XH, Gu ZY, Duan WY, Wang J, Ye ZZ, Shen HB, Shi KH, Hou J, et al. Functional variant in methionine synthase reductase intron-1 significantly increases the risk of congenital heart disease in the han chinese population clinical perspective. Circulation. 2012;125:482–490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang T, Wahlqvist ML, Li D. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid on gene expression of the critical enzymes involved in homocysteine metabolism. Nutr J. 2012;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida M, Suzuki T, Komiya T, Hatashita E, Nishio K, Kazuhiko N, Fukuoka M. Induction of MRP5 and SMRP mRNA by adriamycin exposure and its overexpression in human lung cancer cells resistant to adriamycin. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:432–437. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos-Nino ME, Scapoli L, Martinelli M, Land S, Mossman BT. Microarray analysis and RNA silencing link fra-1 to cd44 and c-met expression in mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3539–3545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolan T, Hands RE, Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1559–1582. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dulucq S, St-Onge G, Gagné V, Ansari M, Sinnett D, Labuda D, Moghrabi A, Krajinovic M. DNA variants in the dihydrofolate reductase gene and outcome in childhood ALL. Blood. 2008;111:3692–3700. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obuchi W, Ohtsuki S, Uchida Y, Ohmine K, Yamori T, Terasaki T. Identification of transporters associated with etoposide sensitivity of stomach cancer cell lines and methotrexate sensitivity of breast cancer cell lines by quantitative targeted absolute proteomics. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:490–500. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.081083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galbiatti ALS, Castro R, Caldas HC, Padovani JA, Pavarino ÉC, Goloni-Bertollo EM. Alterations in the expression pattern of MTHFR, DHFR, TYMS, and SLC19A1 genes after treatment of laryngeal cancer cells with high and low doses of methotrexate. Tumor Biol. 2013;34:3765–3771. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li WW, Waltham M, Tong W, Schweitzer BI, Bertino JR. Increased Activity of γ-Glutamyl Hydrolase in Human Sarcoma Cell Lines: A Novel Mechanism of Intrinsic Resistance to Methotrexate (MTX) In: Ayling JE, Nair MG, Baugh CM, editors. Chemistry and Biology of Pteridines and Folates. Springer US; Boston, MA: 1993. pp. 635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SE, Cole PD, Cho RC, Ly A, Ishiguro L, Sohn KJ, Croxford R, Kamen BA, Kim YI. γ-Glutamyl hydrolase modulation and folate influence chemosensitivity of cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2175–2188. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shubbar E, Helou K, Kovács A, Nemes S, Hajizadeh S, Enerbäck C, Einbeigi Z. High levels of γ-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) are associated with poor prognosis and unfavorable clinical outcomes in invasive breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melling N, Rashed M, Schroeder C, Hube-Magg C, Kluth M, Lang D, Simon R, Möller-Koop C, Steurer S, Sauter G, et al. High-level γ-glutamyl-hydrolase (GGH) expression is linked to poor prognosis in ERG negative prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E286. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galpin AJ, Schuetz JD, Masson E, Yanishevski Y, Synold TW, Barredo JC, Pui CH, Relling MV, Evans WE. Differences in folylpolyglutamate synthetase and dihydrofolate reductase expression in human B-Lineage versus T-lineage leukemic lymphoblasts: Mechanisms for lineage differences in methotrexate polyglutamylation and cytotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:155–163. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Wang Q, Yin FQ, Zhang W, Yan LH, Li L. MTRR silencing inhibits growth and cisplatin resistance of ovarian carcinoma via inducing apoptosis and reducing autophagy. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:1510–1527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotsopoulos J, Hecht JL, Marotti JD, Kelemen LE, Tworoger SS. Relationship between dietary and supplemental intake of folate, methionine, vitamin B(6) and folate receptor α expression in ovarian tumors. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2191–2198. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.López-Cortés A, Echeverría C, Oña-Cisneros F, Sánchez ME, Herrera C, Cabrera-Andrade A, Rosales F, Ortiz M, Paz-Y-Miño C. Breast cancer risk associated with gene expression and genotype polymorphisms of the folate-metabolizing MTHFR gene: A case-control study in a high altitude Ecuadorian mestizo population. Tumor Biol. 2015;36:6451–6461. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leclerc D, Campeau E, Goyette P, Adjalla CE, Christensen B, Ross M, Eydoux P, Rosenblatt DS, Rozen R, Gravel RA. Human methionine synthase: cDNA cloning and identification of mutations in patients of the cblG complementation group of folate/cobalamin disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu LL, Wu JT. Hyperhomocysteinemia is a risk factor for cancer and a new potential tumor marker. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;322:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Tollefsbol TO. Impact on DNA methylation in cancer prevention and therapy by bioactive dietary components. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:2141–2151. doi: 10.2174/092986710791299966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wajed SA, Laird PW, DeMeester TR. DNA methylation: An alternative pathway to cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:10–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W, Braun A, Bauman Z, Olteanu H, Madzelan P, Banerjee R. Expression profiling of homocysteine junction enzymes in the NCI60 panel of human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1554–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bahari G, Hashemi M, Naderi M, Taheri M. Association between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in an iranian population. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2016;10:130–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erčulj N, Kotnik BF, Debeljak M, Jazbec J, Dolžan V. Influence of folate pathway polymorphisms on high-dose methotrexate-related toxicity and survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1096–1104. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.639880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shan F, Liu YL, Wang Q, Shi YL. Thymidylate synthase predicts poor response to pemetrexed chemotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:3274–3280. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Z, Sun J, Zhen J, Zhang Q, Yang Q. Thymidylate synthase predicts for clinical outcome in invasive breast cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:871–878. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaira K, Okumura T, Ohde Y, Takahashi T, Murakami H, Kondo H, Nakajima T, Yamamoto N. Prognostic significance of thymidylate synthase expression in the adjuvant chemotherapy after resection for pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2763–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vrana D, Hlavac V, Brynychova V, Vaclavikova R, Neoral C, Vrba J, Aujesky R, Matzenauer M, Melichar B, Soucek P. ABC transporters and their role in the neoadjuvant treatment of esophageal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E868. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robey RW, Pluchino KM, Hall MD, Fojo AT, Bates SE, Gottesman MM. Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:452–464. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho MM, Hogge DE, Ling V. MDR1 and BCRP1 expression in leukemic progenitors correlates with chemotherapy response in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eadie LN, Dang P, Saunders VA, Yeung DT, Osborn MP, Grigg AP, Hughes TP, White DL. The clinical significance of ABCB1 overexpression in predicting outcome of CML patients undergoing first-line imatinib treatment. Leukemia. 2016;31:75. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.