Abstract

Objective

In England, two primary care incentive schemes were introduced to increase dementia diagnosis rates to two‐thirds of expected levels. This study assesses the effectiveness of these schemes.

Methods

We used a difference‐in‐differences framework to analyse the individual and collective impacts of the incentive schemes: (1) Directed Enhanced Service 18 (DES18: facilitating timely diagnosis of and support for dementia) and (2) the Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS). The dataset included 7529 English general practices, of which 7142 were active throughout the 10‐year study period (April 2006 to March 2016). We controlled for a range of factors, including a contemporaneous hospital incentive scheme for dementia. Our dependent variable was the percentage of expected cases that was recorded on practice dementia registers (the “rate”).

Results

From March 2013 to March 2016, the mean rate rose from 51.8% to 68.6%. Both DES18 and DIS had positive and significant effects. In practices participating in the DES18 scheme, the rate increased by 1.44 percentage points more than the rate for non‐participants; DIS had a larger effect, with an increase of 3.59 percentage points. These combined effects increased dementia registers nationally by an estimated 40 767 individuals. Had all practices fully participated in both schemes, the corresponding number would have been 48 685.

Conclusion

The primary care incentive schemes appear to have been effective in closing the gap between recorded and expected prevalence of dementia, but the hospital scheme had no additional discernible effect. This study contributes additional evidence that financial incentives can motivate improved performance in primary care.

Keywords: dementia, incentive, primary health care, reimbursement

Key points.

Receiving a timely formal diagnosis of dementia can allow patients and their carers to access appropriate care and support packages, prevent avoidable health crises, and plan ahead more effectively.

The combined effect of two incentive schemes was to increase GP dementia registers nationally by around 40 000 cases; this figure would have been almost 50 000 if all practices had taken part.

The schemes had the intended impact on dementia care, suggesting that financial incentives can enhance performance in primary care and may be useful for other disease areas where underdiagnosis is problematic.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a devastating long‐term condition that is projected to place increasing demands on health and care services.1 In the absence of curative treatments, efforts are focused on reducing risk, timely diagnosis, and early intervention.2 General practitioners (GPs) are uniquely placed to coordinate health and social care services for people with dementia and to address the support needs of the family and friends who care for them.

The English Department of Health's Dementia strategy (2009)3 and the Dementia Challenge (2012)4 highlighted the problem of “underdiagnosis”: It was estimated that around half of those with dementia did not have a formal diagnosis. Anticipated benefits of a formal diagnosis included improved access to relevant care and support services; empowering patients and their families to plan their lives better; prevention of avoidable health crises and further cognitive decline (when these are due to vascular risk factors)5; and improvements in the delivery of care and in communication between providers, patients, and carers.6

NHS England, the organisation that leads the National Health Service (NHS) in England, announced a £90M package to improve dementia diagnosis and care.7 The raft of measures included two financial incentive schemes in primary care and one hospital scheme. The aim of these “tools and levers” was to increase diagnosis rates to the level of 67% of the expected number of people with the condition by March 2015 (the so‐called two‐thirds ambition).8 Whilst some interventions were designed to improve dementia care directly, financial incentives have been shown to be powerful levers in effecting behavioural changes in primary and secondary care.9, 10 The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of these financial incentives on diagnostic rates of dementia in primary care.

1.1. Incentive schemes

The two primary care schemes for tackling underdiagnosis were the Directed Enhanced Service 18 (DES18) and the Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS). The schemes were facilitated by a separate pay‐for‐performance scheme, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). Since 2006, the QOF has incentivised good quality care for people with dementia, primarily via a face‐to‐face annual review11, 12, 13 and requires practices to maintain a dementia register. We measured the schemes' effectiveness in tackling underdiagnosis by the gap between the “reported” (recorded) and “expected” numbers on practices' QOF dementia registers.14

DES18 ran from April 2013 to March 2016.15 The scheme encouraged a proactive approach to timely assessment of individuals at risk of dementia, followed‐up by advanced care planning for newly diagnosed patients and a health check for carers. Participating practices received an upfront payment and an annual end‐of‐year payment based on the proportion of national assessments the practice undertook. These payments were funded centrally by annual budgets of £21M for each of the 2 payments, making a total budget of £126M over the 3 years DES18 operated.

DIS operated for 6 months from September 30, 2014, to March 31, 2015, and was intended to support and complement DES18.16 NHS England paid GP practices £55 for each additional patient included on the QOF dementia register, based on the differential between the register at September 30, 2014, and March 31, 2015. Funding available for this scheme totalled £5M.17

A third scheme that incentivised hospitals (FAIR) ran in parallel with the primary care schemes, and we controlled for this in our analyses.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

Details of the datasets analysed are in Appendix S1, and summary statistics for the outcome and control variables in our model are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the outcome and explanatory variables: balanced panel, 2006‐2007 to 2015‐2016

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded dementia register | 39.75 | 36.46 | 0 | 631 | 71 420 |

| Expected dementia register | 80.91 | 64.34 | 0.02 | 1135.91 | 71 420 |

| Mean “rate” (100a recorded/expected) | 49.07 | 21.28 | 0 | 100 | 71 420 |

| DES18 participation, %: 3 y | 79.11 | 71 420 | |||

| DES18 participation, %: 2 y | 15.93 | 71 420 | |||

| DES18 participation, %: 1 y | 3.43 | 71 420 | |||

| DIS participation, % | 75.93 | 71 420 | |||

| Hospital effort (2013‐2014 to 2015‐2016 only)a | 86.06 | 17.14 | 0 | 100 | 21 426 |

| Practice list size (1000) | 7.28 | 4.23 | 0.01 | 60.38 | 71 420 |

| Practice patients 65 or older, % | 16.05 | 5.74 | 0.00 | 47.99 | 71 420 |

| Weighted achievement on the QOF clinical domain | 80.73 | 4.63 | 0.05 | 99.79 | 71 420 |

| GMS contract | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 71 420 |

| Full‐time equivalent GPsb per 1000 patients | 0.57 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 266.67 | 71 420 |

| Patients living in 20% most deprived areas, % | 23.12 | 26.20 | 0.00 | 99.65 | 71 420 |

| Patients living in urban areas, % | 82.71 | 32.45 | 0 | 100 | 71 420 |

Abbreviations. DES18, Directed Enhanced Service 18; DIS, Dementia Identification Scheme; GMS, General Medical Services; GP, General practitioner; N = practice‐years; QOF, Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Hospital effort assumed to be 0 from 2006‐2007 to 2012‐2013.

Excluding retainers/registrars.

2.1.1. Study sample

To be included in our study, practices had to have a QOF dementia register so that recorded and expected numbers of dementia patients could be calculated. We compiled a panel of all eligible English practices that were open during the study period 2006‐2007 to 2015‐2016.

For our base case analyses, our sample was a balanced panel of 7142 practices that contributed data in all 10 years. We undertook two sensitivity analyses. First, we re‐estimated using an unbalanced panel of 7529 practices totalling 74 241 practice‐year observations: this includes practices that closed, opened, split, or merged during the study period. Second, we tested the implications of assuming that the effect of DES18 persisted after a practice had exited the scheme.

2.1.2. Dependent variable

For two practices with identical dementia registers but with very different expected registers, the risk of an “event” (adding a patient to the dementia register) can vary considerably because practices with larger expected registers have greater capacity to improve. We defined our dependent variable as the percentage of expected cases of dementia that was recorded on the dementia register (the “rate”).

The numerator was the number of people recorded on the GP practice's dementia register. The denominator was the expected number of patients aged 65 and over with dementia, which was based on the number, age, and sex of a practice's registered patients living in a nursing home and on the number, age, and sex of the remaining practice patients. We distinguished nursing home patients from community‐dwelling patients because the prevalence of dementia differs between the two groups.18

The General and Personal Medical Services dataset publishes annual data on the number, age, and sex of a practice's registered patients. NHS Digital publishes annual data on the number of nursing home patients in a practice but not by age and sex. We therefore estimated the number of nursing home patients in each age/sex band using values for the national care home population taken from the 2011 Census. Appendix S1 (found in the Supporting Information) details the data sources used for these calculations.

2.1.3. Defining participation

Our key explanatory variables were practice participation in the two schemes. We used the following rules to define participation.

Practices were deemed to have participated in DES18 in a particular year in the period 2013‐2014 to 2015‐2016 if they reported data on the number of dementia assessments undertaken that year, even if that number was zero. Practices not reporting assessment data were deemed to be non‐participants.

Practices participating in DIS were required to report monthly data on recorded dementia diagnoses for September 2014 and for at least one month from October 2014 to March 2015.16 However, some practices that submitted monthly data did not take part in DIS. NHS England provided us with a DIS participant list based on information collected by Local Area Teams for payment purposes.

2.1.4. Covariates

One of the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) national targets,19 the hospital incentive scheme FAIR was also designed to increase diagnostic rates for dementia.

For all patients aged 75 and over who had an emergency admission involving a hospital stay of at least 72 hours, FAIR rewarded hospitals according to their performance on three indicators (1) Find, (2) Assess and Identify, and (3) Refer individuals for specialist diagnosis and follow‐up. Each indicator was scored 0% to 100%, with payment triggered by achieving at least 90% on all 3 indicators in any consecutive 3 months.

To control for the effect of FAIR on QOF dementia registers, we derived a time‐varying measure of hospital effort based on the first two FAIR indicators only, because the third indicator (“Refer”) was defined differently in the final year, and its performance data were not published.

We converted the two hospital trust‐level scores to weighted GP practice average values. To match the CQUIN target population, we extracted Hospital Episode Statistics data on the number of emergency admissions in each GP practice for all people 75 and over with inpatient stays of at least 72 hours. We attributed hospital “effort” to the practice as the weighted average CQUIN score, where the weights were the proportion of each practice's emergency admissions (as defined above) to each hospital. The CQUIN scheme operated from 2012‐2013, but data were not collected that year. Therefore, this variable was set to zero for all practices for the period before 2013‐2014.

As dementia registers are affected by factors other than incentive schemes, the analysis also adjusted for the following time‐varying practice characteristics: practice list size (ie, number of registered patients), the proportion of patients aged 65 and over, a measure of overall achievement on the QOF clinical domains,20 whether the practice had a General Medical Services contract, deciles of the practice doctor/patient ratio (full‐time equivalent GPs per 1000 registered patients), practice deprivation (the percentage of practice patients living in the 20% most deprived small areas in England), and a measure of access (the percentage of patients living in urban areas).

To adjust for regional effects, we included variables for each practice's Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) using NHS England's list of active practices. CCGs for practices that had closed were identified by linking a National Audit Office mapping file to the Office for National Statistics' Postcode Directory.

2.2. Statistical modelling

Our unit of analysis was the GP practice. We modelled the two practice schemes, DES18 and DIS, as binary participation indicators and evaluated their impact on the rate as defined above. Our econometric design needed to accommodate multiple incentive schemes as well as the different times the schemes were introduced and taken up.

We identified different types of participants for the 3‐year DES18 scheme and for the 6‐month DIS scheme, distinguishing practices into categories according to the number and order of years of participation (Table 2). For example, a practice that only participated in the first two years of DES18 (but not the third year) was categorised as “Y/Y/N.”

Table 2.

Participation in DES18 or DIS: balanced panel, 2006‐2007 to 2015‐2016a

| Practice‐years | Percent | Mean Dementia Register | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DES18 participationb | |||

| Years of participation: 3 | 56 500 | 79.11 | 42.67 |

| Y/Y/Y | 56 500 | 79.11 | 42.67 |

| Years of participation: 2 | 11 380 | 15.93 | 29.29 |

| Y/Y/N | 1280 | 1.79 | 33.08 |

| Y/N/Y | 1420 | 1.99 | 28.31 |

| N/Y/Y | 8680 | 12.15 | 28.89 |

| Years of participation: 1 | 2450 | 3.43 | 25.54 |

| Y/N/N | 440 | 0.62 | 31.82 |

| N/Y/N | 700 | 0.98 | 22.85 |

| N/N/Y | 1310 | 1.83 | 23.63 |

| No participation | 1090 | 1.53 | 31.09 |

| N/N/N | 1090 | 1.53 | 31.09 |

| Total | 71 420 | 100 | 39.75 |

| DIS participation | |||

| No | 17 190 | 24.07 | 34.45 |

| Yes | 54 230 | 75.93 | 41.43 |

| Total | 71 420 | 100 | 39.75 |

Abbreviations: DES18, Directed Enhanced Service 18; DIS, Dementia Identification Scheme.

As this is a balanced panel, the number of practices contributing data can be inferred by dividing practice‐years by 10.

Participation is indicated by Yes (Y), non‐participation by No (N).

Our methodological framework was a “difference‐in‐differences” (DID) design.21 We compared the difference in rates before and after the introduction of the schemes by participation type using linear mixed effects models. These models assume that, in the absence of the intervention, outcome differences between participants and non‐participants are constant over time. Therefore, any differences in rates observed in the postintervention period over and above the time trend can be attributed to the incentive scheme. This effect is measured by the coefficient on the policy variable. We applied a DID model with multiple periods22, 23, 24 (technical details are in Appendix S2).

The postestimation “predict” function was used to derive predicted rates under hypothetical participation scenarios, enabling us to estimate the national impact on dementia registers. Analyses were undertaken in Stata v14.2.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive analysis

From March 2013 to March 2016, the total number of people listed on GP dementia registers in England increased from 309 461 to 432 727, ie, a net rise of 123 266 individuals. The number diagnosed will be higher than this figure, because some newly diagnosed patients replaced individuals on the register who died.

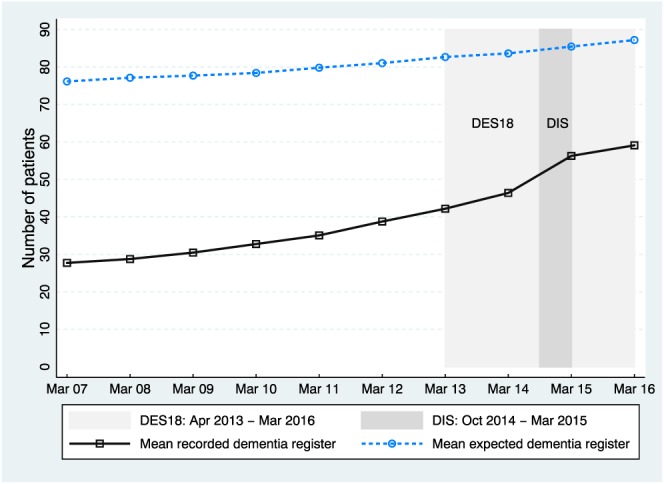

Figure 1 shows how the gap between the mean expected and mean recorded dementia registers varied over time. There was an upward trend in recorded dementia disease registers, whereas the rate of increase in expected values was lower. Consequently, the gap between recorded and expected registers has narrowed. The periods when DES18 and DIS were active are shown as shaded areas.

Figure 1.

Gap between mean recorded dementia register and mean expected dementia register. Abbreviation: DES18, Directed Enhanced Service 18; DIS, Dementia Identification Scheme [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

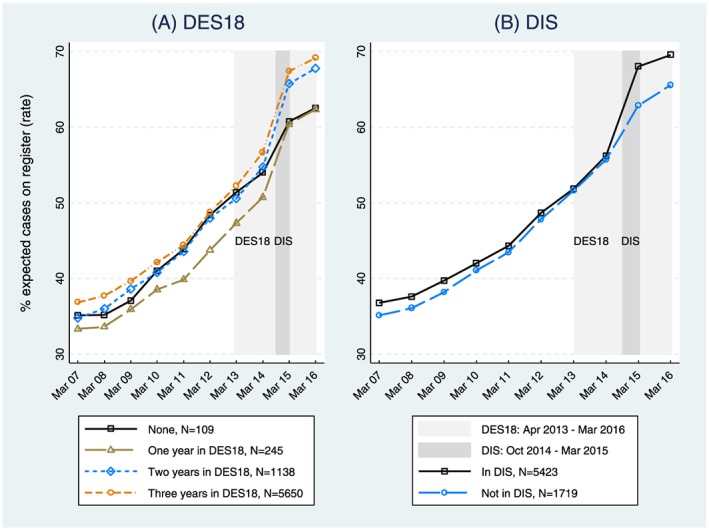

From March 2013 to March 2016, the mean percentage of expected cases that was recorded on GP dementia registers increased from 51.8% to 68.6%. Figure 2 shows how this rate varied by participation in (a) DES18 and (b) DIS. By March 2016, practices participating in DES18 in all 3 years had a smaller gap between recorded and expected registers (ie, a higher outcome rate) on average than other practices. When comparing participation in DIS, the unadjusted data show a distinct divergence in trends around the time the intervention was introduced.

Figure 2.

Trends in mean practice outcome rates by years of participation in A, Directed Enhanced Service 18 (DES18) and B, Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Regression analysis

Whilst the unadjusted data suggested that practices participating in the schemes closed the gap between their recorded and expected registers at a faster rate than non‐participants, the DID analysis tested whether the observed differences were explained by confounding factors.

Table 3 shows results from the linear random effects regression model applied to the balanced panel. The upward trend in the rates shown in Figure 2 is reflected in the increasing coefficients of the year dummies (beta coefficients; Appendix S2). Relative to its value in 2006‐2007, the rate increased by 0.35 percentage points in 2007‐2008, by 16.4 percentage points by 2012‐2013, and by 31.0 percentage points by 2015‐2016.

Table 3.

Linear random effects results: balanced panel, 2006‐2007 to 2015‐2016

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| FY is 2006‐2007 (ref) | ||

| FY is 2007‐2008 | 0.345** | [0.096, 0.593] |

| FY is 2008‐2009 | 2.397*** | [2.073, 2.721] |

| FY is 2009‐2010 | 5.795*** | [5.427, 6.162] |

| FY is 2010‐2011 | 7.908*** | [7.508, 8.307] |

| FY is 2011‐2012 | 12.556*** | [12.121, 12.992] |

| FY is 2012‐2013 | 16.419*** | [15.934, 16.903] |

| FY is 2013‐2014 | 19.022*** | [17.563, 20.482] |

| FY is 2014‐2015 | 26.562*** | [24.814, 28.311] |

| FY is 2015‐2016 | 30.977*** | [29.329, 32.624] |

| Practice participation in DES18 in 2013‐2014/2014‐2015/2015‐2016a | ||

| N/N/N (ref) | ||

| Y/Y/Y | 2.010 | [‐0.638, 4.658] |

| Y/Y/N | 1.275 | [‐2.411, 4.960] |

| Y/N/Y | ‐0.207 | [‐3.562, 3.148] |

| Y/N/N | ‐0.909 | [‐5.114, 3.295] |

| N/Y/Y | ‐0.720 | [‐3.523, 2.082] |

| N/Y/N | ‐1.843 | [‐6.382, 2.695] |

| N/N/Y | ‐3.438* | [‐6.843, ‐0.033] |

| Participation in DIS | 0.770 | [‐0.030, 1.570] |

| Policy variable (DES18) | 1.439*** | [0.669, 2.210] |

| Policy variable (DIS) | 3.594*** | [2.785, 4.403] |

| Hospital effort (FAIR) | 0.008 | [‐0.007, 0.024] |

| Practice list size (in 1000) | 0.255*** | [0.172, 0.338] |

| % of practice patients 65 or older | ‐0.559*** | [‐0.651, ‐0.467] |

| QOF achievement in the clinical domain | 0.301*** | [0.253, 0.349] |

| GMS contract | ‐0.650* | [‐1.187, ‐0.112] |

| Deciles of FTE GPs per 1000 patients | ||

| Decile 1 (ref) | ||

| Decile 2 | 0.096 | [‐0.590, 0.781] |

| Decile 3 | ‐0.013 | [‐0.702, 0.675] |

| Decile 4 | 0.077 | [‐0.609, 0.764] |

| Decile 5 | ‐0.066 | [‐0.756, 0.624] |

| Decile 6 | 0.182 | [‐0.515, 0.879] |

| Decile 7 | 0.294 | [‐0.397, 0.985] |

| Decile 8 | 0.168 | [‐0.534, 0.871] |

| Decile 9 | 0.385 | [‐0.348, 1.118] |

| Decile 10 | 0.518 | [‐0.287, 1.322] |

| % of practice patients living in 20% most deprived areas | 0.033** | [0.012, 0.054] |

| % of practice patients living in urban areas | 0.019** | [0.007, 0.031] |

| Within R‐squared | 0.489 | |

| Between R‐squared | 0.196 | |

| Overall R‐squared | 0.360 | |

| Standard deviation of practice random effect (sigma_u) | 12.204 | |

| Intraclass correlation (rho) | 0.508 | |

Abbreviations. DES18, Directed Enhanced Service 18; DIS, Dementia Identification Scheme; FAIR, Find, Assess and Identify, and Refer; FTE, full‐time equivalent; FY, financial year; GMS, General Medical Services; GP, General practitioner; QOF, Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Participation is indicated by yes (Y), non‐participation by no (N).

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001; models also adjust for Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) (results not shown).

The estimates for the DES18 participation groups showed no difference between the rates of practices that never participated in DES18 and the other practice groups in the preintervention period, with the exception of practices that participated only in the final year of the scheme (participation variables are the gamma coefficients; Appendix S2). Similarly, the rates for DIS participants did not differ significantly from those of non‐participants in the preintervention period.

The policy variables (delta coefficients; Appendix S2) for DES18 were positive and significant. The DES18 scheme increased the rate for the intervention practices by 1.44 percentage points more than the increase in the rate for non‐participating practices. DES18 had a significant effect in reducing the gap between recorded and expected registers (P < .001). The effect of DIS was larger with an estimated 3.59 percentage points increase in the rate (P < .001).

The effect of the hospital scheme (FAIR) was not statistically significant. Higher overall achievement on the QOF clinical domain presumably reflected better overall practice quality that helped close the gap between the recorded and expected prevalence of dementia. Practices with larger proportions of patients living in urban areas and practices with more disadvantaged patients had smaller gaps between recorded and expected dementia registers (ie, higher rates). Practices with a higher proportion of individuals aged 65 and above had significantly lower rates (P < .001), as did practices with a General Medical Services contract (P < .05).

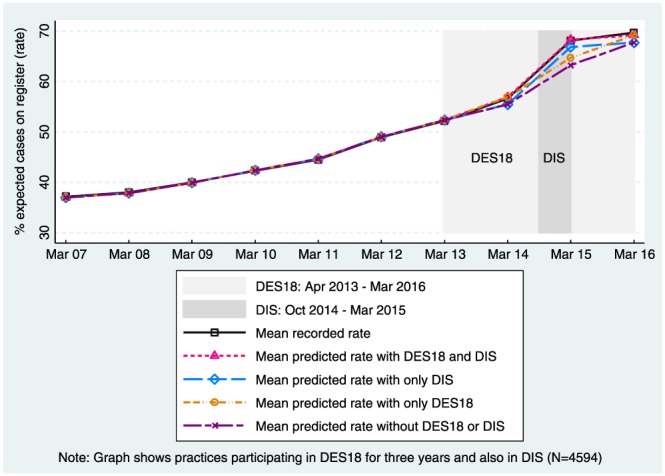

To quantify the added value of the schemes, we predicted the rates under hypothetical participation scenarios. Figure 3 shows the effects of the schemes for the 4594 practices that participated in DES18 in all 3 years and that also participated in DIS. The black line shows the mean recorded rate. The other 4 lines depict the predicted rates under 4 scenarios of practice participation: (1) both in DES18 and DIS, (2) only in DIS, (3) only in DES18, (4) neither in DES18 nor in DIS.

Figure 3.

Trends in mean of the recorded and predicted practice outcome rates: Directed Enhanced Service 18 (DES18) and Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The first scenario is the mean predicted rate assuming practices participated fully in both DES18 and DIS (as they did in this subsample). The last three scenarios are hypothetical (predicted) counterfactuals; for instance, the fourth scenario predicts the rates that would have been observed had these practices not participated in either scheme.

Had all practices in the unbalanced panel participated fully in both schemes, these predicted values suggest that national dementia registers would have increased by 48 685. As participation levels were suboptimal, the net effect of the schemes was to increase registers by 40 767 (59% of which was attributable to DES18).

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

The results were robust to two sensitivity analyses (results are shown in Appendix S3). First, we applied the model to the unbalanced panel of 7529 practices totalling 74 241 practice‐year observations. Both policy variables remained significant with the size of the effects very similar to the estimates from the balanced panel analysis.

The base case analysis assumed that the effects of the schemes did not persist beyond the period of active participation. In the second sensitivity analysis, we estimated a model that assumed the effect of the DES18 persisted after the practice exited the scheme. In this specification, four types of practices were defined by the year in which the practice entered the scheme (if at all). Under this design, the change in rate between 2012‐2013 and 2015‐2016 for each of the participating groups relative to the change in rate for the non‐participating group did not vary by participation status each year, as in our base model. The DES18 policy effect (1.38) was significant and similar in size to the effect estimated in our base model (1.44).

4. DISCUSSION

This national study of two primary care financial incentive schemes provides evidence that they helped to tackle the problem of underdiagnosis in dementia. On average, a practice's QOF dementia register rose from 28 individuals (March 2007) to 42 prior to the first scheme's introduction (March 2013) and stood at 59 when the schemes ended (March 2016). Participation in DES18, which incentivised timely assessment and support by general practice, contributed to these numbers by increasing dementia registers amongst participating practices by 1.17 individuals each year on average. Participation in the DIS, which paid practices £55 for each “net” addition to the dementia register over a 6‐month period, had an even larger impact, delivering an average net increase in registers of 2.98.

In common with most evaluations of pay‐for‐performance schemes, this study faced several methodological challenges,9 10 which we discuss below.

Ideally, participation in the schemes would have been randomly allocated to minimise the risk of known and unknown biases affecting results. However, DID analysis is a good alternative when randomisation is not possible because policies have been rolled out nationally. Difference‐in‐differences assumes the intervention groups have a common trend with the control group, and the regression analysis (participation coefficients) supports that assumption. We controlled for practice characteristics we believed could affect diagnosis rates but cannot rule out the possibility that other factors we could not measure, such as the availability of memory clinics, may have influenced results.

A key challenge in this study was defining participation in the schemes. Some practices could be clearly identified as participants or non‐participants, but others were “grey” practices that signed up to the DES18 scheme but then, apparently, did nothing—or so the assessments data suggest. Are these practices “failed” participants (as we assumed) or non‐participants? This matters because our models presuppose a clear distinction between the intervention and control groups. For DIS, NHS England provided a list of participants. The list was based on data provided by their Local Area Teams for payment purposes and was subject to numerous checks.

Our study relied on administrative datasets that are subject to the usual challenges in relation to coding errors and missing data. Data on FAIR were only available for 2 of the 3 indicators in 2015/2016, so our measure only partially captures hospitals' efforts in diagnosing dementia patients. For approximately 15% of practices that had fewer than 6 patients in nursing homes, data were suppressed to prevent disclosure. We imputed these missing data with random values between 1 and 5. In addition, the age/sex distribution of nursing home patients in practices is unknown, so we imputed national distributions (Appendix S1).

We do not know of any previous studies quantifying the impact of schemes to boost diagnosis rates of dementia. However, the targeting of financial incentives on GPs in order to achieve quality improvements underpins the major policy initiative of the QOF programme. Research on the QOF suggests that overall, this policy has been successful in promoting quality improvements—although at relatively modest levels which tend to reduce over time—in the incentivised conditions.12, 13, 25, 26 In our study, both DES18 and the DIS schemes appeared effective. The impact of DIS is unsurprising given the direct and time‐limited nature of the incentive, which was designed to focus attention on the issue of underdiagnosis of dementia. There were calls from doctors for DIS to be withdrawn,27 criticising it as “cash for diagnosis”28 and “unethical and dangerous for patients,”29 nonetheless, over three‐quarters of practices opted in. We also found evidence suggesting the effects of both schemes persisted after practices had exited the schemes, which supports findings from an evaluation of the withdrawal of QOF indicators.30

The hospital CQUIN scheme, FAIR, appears not to have had the expected trickledown effect on GP registers. Previous research has found little evidence of any effect of CQUIN schemes aside from those involving hip fracture.31

NHS England achieved its two‐thirds ambition for dementia in November 2015.5 During the years when the schemes were active, total numbers on the dementia registers increased by 123 266. However, only one‐third (40 767) of these additional cases are attributable to the 2 schemes. The schemes' effect on the number of newly diagnosed individuals will be higher than this figure, because some additions to the register replace individuals who have died.

Total expenditure on the schemes has not been published, but we estimate the budget to be around £131M, comprising £5M for DIS17 and £42M available in each of the 3 years for DES18.32 Despite the controversy over DIS, our results illustrate that direct, targeted, and time‐limited financial incentives for GPs work, and as a result, quality of care has likely been enhanced for those individuals whose dementia was identified through the schemes. We also found evidence suggesting that the impact of the schemes persists after they ended, although our evaluation had limited follow‐up. Policymakers may consider repeating this approach either for dementia or for other disease areas where early diagnosis is considered beneficial.

Remaining gaps in the evidence base include the wider benefits and unintended consequences of the schemes and the true cost of delivering the schemes, as opposed to the budgeted expenditure. Although our study demonstrated the schemes were successful in closing the diagnosis gap, a comprehensive assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of using financial incentives to improve diagnosis rates would require further research in these two key areas.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supporting information

Data S2 Supporting information

Data S3 Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank participants at the Health Economics Study Group (HESG) meeting in Birmingham (January 2017) for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper, our advisory groups for valuable insights and advice, and NHS England for providing the list of DIS participants. We are also grateful to two reviewers for their insightful comments.

The paper is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme (Economics of Social and Health Care; PRP Ref: 103 0001). The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, arm's length bodies, or other government departments.

Mason A, Liu D, Kasteridis P, et al. Investigating the impact of primary care payments on underdiagnosis in dementia: A difference‐in‐differences analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:1090–1097. 10.1002/gps.4897

Footnotes

Numbers of practices with imputed random value: 2009/2010: 1085 (15.2%), 2010/2011: 1107 (15.5%), 2011/2012: 1102 (15.4%).

REFERENCES

- 1. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):102 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor JP. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350. h3029. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health . Living Well With Dementia: A national dementia strategy. London: Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health . The Prime Minister's Challenge on Dementia: Delivering Major Improvements in Dementia Care and Research by 2015. London: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burns A, Bagshaw P. A New Dementia Currency in Primary Care, 2 March. NHS England: blog; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. NHS England . Dementia identification scheme: guidance and frequently asked questions In: Operations NEC Eds. In: Gateway reference number: 02504. 2014th ed.; 2014:9. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health . NHS to tackle long waits for dementia assessments. Press Release; 2014.

- 8. NHS England . Everyone Counts : Planning for Patients 2014/15 to 2018/19. NHS England: Leeds; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, et al. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7). CD009255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9). CD008451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goddard M, Kasteridis P, Jacobs R, Santos R, Mason A. Bridging the gap: the impact of quality of primary care on duration of hospital stay for people with dementia. J Integr Care. 2016;24(1):15‐25. 10.1108/JICA-11-2015-0045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kasteridis P, Mason A, Goddard M, et al. The influence of primary care quality on hospital admissions for people with dementia in England: a regression analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kasteridis P, Mason A, Goddard M, et al. Risk of care home placement following acute hospital admission: effects of a pay‐for‐performance scheme for dementia. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 2016;11(5):e0155850 10.1371/journal.pone.0155850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. NHS England . General Practice Outcome Standards: Methodology for Assessing Variation (Version 2.1). An Introduction to an England Approach to Improve Quality. NHS England: Access and Patient Experience in General Practice; 2016:13. [Google Scholar]

- 15. NHS Commissioning Board . Enhanced service specification: facilitating timely diagnosis and support for people with dementia: NHS Commissioning Board, 2013:10.

- 16. NHS England . Enhanced Service Specification: Dementia Identification Scheme. 15 Leeds: NHS England; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Millett D. Practices to earn £55 per extra patient diagnosed with dementia. GP Online, 2014.

- 18. Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, et al. A two‐decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the cognitive function and ageing study I and II. Lancet. 2013;382(9902):1405‐1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NHS Commissioning Board . Commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN): 2013/14 guidance, 2012:37.

- 20. Santos R, Gravelle H, Propper C. Does quality affect Patients' choice of doctor? Evidence from England. Econ J. 2017;127(600):445‐494. 10.1111/ecoj.12282 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ashenfelter O, Card D. Using the longitudinal structure of earnings to estimate the effect of training programs. Rev Econ Stat. 1985;67(4):648‐660. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences‐in‐differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119(1):249‐275. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hansen CB. Generalized least squares inference in panel and multilevel models with serial correlation and fixed effects. J Econometr. 2007;140(2):670‐694. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wooldridge J. New developments in econometrics. Lecture 11: Difference‐in‐differences estimation. Cemmap Lecture Notes, 2009.

- 25. Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):368‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doran T, Kontopantelis E, Valderas JM, et al. Effect of financial incentives on incentivised and non‐incentivised clinical activities: longitudinal analysis of data from the UK quality and outcomes framework. BMJ. 2011;342(7814):d3590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3590). [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brunet M. An open letter to Simon Stevens, NHS chief executive, and Alistair Burns, national clinical lead for dementia. BMJ. 2014;349 10.1136/bmj.g6666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kmietowicz Z. Doctors condemn "unethical" 55 payment for every new dementia diagnosis. BMJ. 2014;349:g6424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kmietowicz Z. Axe the £55 payment for dementia diagnosis, say doctors. BMJ. 2014;349:g6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kontopantelis E, Springate D, Reeves D, et al. Withdrawing performance indicators: retrospective analysis of general practice performance under UK quality and outcomes framework. BMJ. 2014;348, g330. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McDonald R, Zaidi S, Todd S, et al. Evaluation of the commissioning for quality and innovation framework: Final report: University of Nottingham, University of Manchester, 2013.

- 32. NHS England . NHS England, government and BMA agree new GP contract for 2016/17. NHS England News, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Supporting information

Data S2 Supporting information

Data S3 Supporting information