Abstract

Choline is critical for normative function of 3 major pathways in the brain, including acetylcholine biosynthesis, being a key mediator of epigenetic regulation, and serving as the primary substrate for the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase pathway. Sufficient intake of dietary choline is critical for proper brain function and neurodevelopment. This is especially important for brain development during the perinatal period. Current dietary recommendations for choline intake were undertaken without critical evaluation of maternal choline levels. As such, recommended levels may be insufficient for both mother and fetus. Herein, we examined the impact of perinatal maternal choline supplementation (MCS) in a mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease, the Ts65Dn mouse relative to normal disomic littermates, to examine the effects on gene expression within adult offspring at ∼6 and 11 mo of age. We found MCS produces significant changes in offspring gene expression levels that supersede age-related and genotypic gene expression changes. Alterations due to MCS impact every gene ontology category queried, including GABAergic neurotransmission, the endosomal-lysosomal pathway and autophagy, and neurotrophins, highlighting the importance of proper choline intake during the perinatal period, especially when the fetus is known to have a neurodevelopmental disorder such as trisomy.—Alldred, M. J., Chao, H. M., Lee, S. H., Beilin, J., Powers, B. E., Petkova, E., Strupp, B. J., Ginsberg, S. D. Long-term effects of maternal choline supplementation on CA1 pyramidal neuron gene expression in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: hippocampus, laser capture microdissection, early choline delivery, microarray, trisomic

Choline is an essential nutrient necessary for proper health and development, especially within the brain, where it is required for appropriate function of multiple key pathways. Choline is requisite for biosynthesis of acetylcholine, a critical neurotransmitter that regulates multiple neurodevelopmental niches, including proliferation, migration, and synapse formation among others (1–4). Choline is the primary dietary methyl donor for gene expression regulation through epigenetic programming (5–8). Choline is also a key substrate in the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) pathway, from which several structural membrane phospholipids, including sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine (PC), are generated (9, 10). High demand for choline is found during pregnancy in human and rodent models (11–13), and choline levels were depleted in pregnant dams when consuming chow with standard choline levels (14, 15). These reports support the hypothesis that current dietary recommendations for choline are insufficient, especially during pregnancy and lactation (3, 11, 13, 16). Thus, increasing dietary choline intake during pregnancy may be an inexpensive and well-tolerated approach to improve the healthspan of offspring, particularly those with identified genetic or neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Notably, human trials exploring maternal choline supplementation (MCS) in the third trimester using choline in the normal (480 mg) and upper (930 mg) reference range demonstrate improvement in infant information-processing speed with consistent results obtained from individuals 4–13 mo of age with no known neurodevelopmental abnormalities or delays (11). This study of human gestation shows increased choline levels through MCS do not mitigate the depletion of choline levels seen in mothers (11). Another human trial utilized the choline metabolite PC as a perinatal supplement, which also showed cognitive improvement in infants (17). Recent MCS clinical trials also have shown promise for prenatal alcohol exposure (18, 19), indicating its utility for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders. However, not all MCS-based clinical trials have shown cognitive improvements in offspring (20), suggesting the need for continued preclinical studies to understand the potential underlying mechanisms of action and full translational capability of this nutrient, especially in models of human neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders including Ts65Dn mice.

From a translational perspective, MCS is a well-tolerated, well-established feeding paradigm in which rodent dams are given increased choline in their diet, either in the chow or drinking water, during gestation through weaning. MCS has been shown to positively affect multiple aspects of learning and memory in offspring of both normal rodents and in disease models. For example, benefits of MCS treatment have been observed in numerous rodent models, including aging, seizure disorder, prenatal alcohol syndrome, autism, Down syndrome (DS), and Rett syndrome among others (3, 9).

DS is caused by the triplication of human chromosome 21 (HSA21) and is the primary genetic cause of intellectual disability. Complicating the cognitive deficits seen in DS, these individuals develop pathologic changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in early midlife, including amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)–positive senile plaque formation, neurofibrillary tangles, degeneration of the cholinergic basal forebrain pathway, and early endosomal abnormalities (21–28). Several mouse models of DS have been generated to recapitulate the human trisomic phenotype. For example, the relatively new Dp16 murine model contains 102 protein-coding transcripts orthologous to HSA21, and the Tc1 model contains the partial human HSA21 chromosome with 125 protein-coding transcripts inserted into the mouse genome (29–32). Although the Tc1 model replicates the HSA21 chromosome, mosaic expression is found within different cell types (29, 31, 32). To date, the most widely studied model of DS and AD is the segmental trisomy Ts65Dn mouse line containing 90 protein-coding transcripts orthologous to HSA21 (29, 31, 32). This model closely recapitulates many features of human DS neuropathology (33–40), although these mice do not form senile plaques or neurofibrillary tangles. However, Ts65Dn mice display age-dependent, AD-like, hippocampal-dependent learning and memory deficits and significant basal forebrain cholinergic neuron (BFCN) degeneration during their early midlife, along with septohippocampal circuit vulnerability (21, 38, 40, 41). The overwhelming majority of preclinical DS studies have employed the Ts65Dn mouse model (29, 30).

Several studies of perinatal MCS by our collaborative laboratory group in Ts65Dn mice have shown beneficial effects in septohippocampal-dependent attentional tasks (42, 43) and spatial cognition (44, 45). The cognitive benefits of MCS treatment persist well into midage and old-age (12–17 mo old at testing) (43–45). Likewise, neuronal abnormalities seen in the septohippocampal circuit are also reduced by MCS treatment in adult offspring, including normalization of hippocampal neurogenesis and increases in the size, density, and number of medial septal nucleus BFCNs (2, 44–46). MCS increases metabolic activity of the PEMT pathway in hippocampal and basal forebrain tissue in Ts65Dn and normal disomic (2N) littermates, including de novo synthesis of PC-enriched metabolites associated with docosahexaenoic acid metabolism (10). Notably, MCS had a significantly greater effect on hippocampal and basal forebrain PEMT activity in trisomic mice compared with 2N littermates (10), suggesting its use as a therapeutic in DS. These results indicate that neurodevelopmental disorders, including DS, increase the demand for choline, especially in the brain, giving rise to the idea that neurologic dysfunction may be partially ameliorated by higher choline intake during neurodevelopment.

Although studies have looked at individual gene expression changes in MCS-treated offspring, including cAMP response element-binding protein (Creb) (47), Igf-2 (48, 49), MAPK 1 (Erk2) (47), and nerve growth factor (50) among others, these studies were predominantly performed in rats and only examined a handful of key genes in relatively few pathways. Additionally, these studies examined admixed neuronal, glial, and vascular cell populations and, in some cases, multiple admixed brain regions. Previous work in our lab has shown that MCS attenuated or reversed a subset of transcripts whose aberrant gene expression was seen in the murine DS phenotype (Ts65Dn mice) compared with 2N controls (51). Because of the large and complex datasets emanating from these single population analyses, global MCS gene expression level changes within CA1 pyramidal neurons stratified by age or genotype have not been performed, which are crucial to understand what MCS does mechanistically to gene expression within a vulnerable hippocampal cell type in an aging paradigm relevant toward understanding the pathophysiology of DS and AD. Herein, we examined gene expression changes due to MCS in CA1 pyramidal neurons within 2 mouse phenotypes, Ts65Dn (DS and AD model) and 2N littermates at 2 adult timepoints, ∼6 and 11 mo old, through single population microaspiration via laser capture microdissection (LCM) coupled with custom-designed microarray analysis and gene ontology category (GOC) pathway assessment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and maternal dietary protocol

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Nathan Kline Institute and New York University Langone Medical Center, and were in full accordance with National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) guidelines. Breeder pairs (female Ts65Dn and male C57Bl/6J Eicher × C3H/HeSnJ F1 mice) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and mated at the Nathan Kline Institute. Upon arrival, breeder pairs were assigned to receive 1 of 2 choline-controlled experimental diets: control rodent diet containing 1.1 g/kg choline chloride (AIN-76A; Dyets, Bethlehem, PA, USA) or choline-supplemented diet containing 5.0 g/kg choline chloride (AIN-76A; Dyets), as previously described (40, 43, 52). The choline-supplemented diet provides ∼4.5 times the concentration of choline consumed by the control dams and is within the normal physiologic range (53). The control diet supplies an adequate level of choline. Thus, offspring from dams on the control diet are not choline deficient. Breeder pairs were provided ad libitum access to water and their assigned diets. Standard cages contained paper bedding and several objects for enrichment (i.e., plastic igloo, t-tube, and cotton square nestlet). Mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle under temperature- and humidity-controlled conditions.

Tissue preparation

Pups born to choline-supplemented (designated as Ts+ and 2N+) or unsupplemented maternal choline (designated as Ts and 2N) dams were weaned on postnatal d 21 and provided ad libitum access to water and control diet. Tail clips were taken and genotyped as described by Duchon et al. (54). Pups were aged to ∼6 and 11 mo old and brain tissues accessed. Mice used in this study included: 2N+ n = 11 (∼6 mo old), n = 8 (∼11 mo old); 2N n = 12 (∼6 mo old), n = 7 (∼11 mo old); Ts+ n = 16 (∼6 mo old), n = 8 (∼11 mo old); and Ts n = 19 (∼6 mo old), n = 6 (∼11 mo old). Male and female offspring were utilized. Mice were given an overdose of ketamine (83 mg/kg) and xylazine (13 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde buffered in 0.15 M phosphate buffer. Tissue blocks containing the dorsal hippocampus were paraffin embedded, and 6-μm–thick tissue sections were cut in the coronal plane on a rotary microtome for immunocytochemistry as previously described (55–57). RNase-free precautions were employed, and solutions were made with 18.2 mMega Ohm RNase-Free Water (Nanopure Diamond; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Single-cell microaspiration and terminal continuation RNA amplification

LCM and terminal continuation (TC) RNA amplification procedures have been previously described in detail by our group (55, 58–61). Briefly, individual CA1 pyramidal neurons were microaspirated via LCM (Arcturus PixCell IIe; Thermo Fisher Scientific). One hundred cells were captured per reaction for population cell analysis (57, 58). Microarrays (containing 100 LCM-captured CA1 neurons each) were performed per mouse brain (2–5 times/ mouse; a total of 202 custom-designed arrays for ∼6-mo-old mice and a total of 111 custom-designed arrays total for ∼11-mo-old mice). The full TC RNA amplification protocol is available at the Center for Dementia Reseach database (http://cdr.rfmh.org). This method entails synthesizing first-strand cDNA complementary to the RNA template, reannealing the primers to the cDNA, and, finally, in vitro transcription using the synthesized cDNA as a template. Briefly, microaspirated CA1 neurons were homogenized in Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), chloroform extracted, and precipitated (55, 59, 62, 63). RNAs were reverse transcribed, and single-stranded cDNAs were then subjected to RNase H digestion and reannealing of the primers to generate cDNAs with double-stranded regions at the primer interfaces. Single-stranded cDNAs were digested, and samples were purified by Vivaspin 500 columns (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany). Hybridization probes were synthesized by in vitro transcription using 33P, and radiolabeled TC RNA probes were hybridized to custom-designed cDNA arrays without further purification.

Microarray platforms and hybridization

Array platforms consist of 1 μg of linearized cDNA purified from plasmid preparations adhered to high-density nitrocellulose (Hybond XL; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) using an arrayer robot (VersArray; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) (61, 64). Each cDNA or expressed sequence-tagged cDNA (EST) was verified by sequence analysis and restriction digestion. Mouse and human clones were employed on the custom-designed array. Approximately 576 cDNAs or ESTs were utilized for the ∼6-mo-old cohort, and ∼649 genes were utilized for the ∼11-mo-old cohort, organized into 22 GOC categories. Arrays used for ∼11-mo-old mice included genes newly available or implicated in DS and AD pathology. Additional genes principally composed 3 GOC classifications: protein phosphatases and kinases, stress response markers, and sirtuins. The majority of genes are represented by 1 transcript on the array platform, although the neurotrophin (Ntf) receptors Ntrk1, Ntrk2 and Ntrk3 are represented by ESTs that contain the extracellular domain as well as the tyrosine kinase domain (65, 66).

Quantitative PCR and NanoString nCounter

A second independent, mixed-gender cohort of ∼6-mo-old mice (n = 9/condition for 2N+, 2N, Ts+, and Ts) was perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, and the CA1 subregion was microdissected tissue as previously described (51, 62, 63) and RNA extracted for quantitative PCR (qPCR) and NanoString nCounter (NanoString Technologies; Seattle, WA, USA) analyses. Taqman qPCR primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were utilized for the following genes: CREB binding protein (Crebbp; Mm01342452_m1), embryonic lethal abnormal vision–like 1 (Elavl1; m01243908_m1), and G-protein, α-z polypeptide (Gnaz; Mm01150269_m1). Samples were assayed in triplicate on a real-time qPCR cycler (PikoReal; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 96-well optical plates with coverfilm as previously described (51, 55, 59, 62, 63, 67). Standard curves and Ct were generated using standards obtained from total mouse brain RNA. The ΔΔCt method was employed to determine relative gene level differences between study groups (65, 67, 68). Succinate dehydrogenase A qPCR products were used as a control because this probe demonstrated the least amount of variability of the 3 control primers tested: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Mm99999915_g1), hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Mm01318747_g1), and succinate dehydrogenase A (Mm01352360_m1; unpublished results). Negative controls consisted of the reaction mixture without input RNA. The 4 study groups (Ts+, Ts, 2N+, and 2N) were compared with respect to PCR product synthesis for each gene tested.

NanoString nCounter was performed on codesets designed in conjunction with NanoString Technologies utilizing 55 genes known to be involved in DS and AD pathology with 5 internal negative controls and 5 internal positive housekeeping control genes. Codesets were designed prior to analysis of the present microarray findings and based on previously published reports of gene expression changes in DS and AD pathology. Normalization was performed utilizing the NanoString Reference (housekeeping) gene normalization protocol (69).

Statistical analyses

Statistical procedures for custom-designed microarray analysis have been previously described in detail (51, 62, 63, 70, 71). Gene expression differences due to genotype or dietary condition were assessed with respect to the hybridization signal intensity ratio of the total signal of all array genes. For each gene, the signal intensity ratio was modeled as a function of the mouse study group, using mixed effects models with random mouse effect to account for the correlation between repeated assays on the same mouse (72). Significance was judged at the level α = 0.01 (2-sided). A false discovery rate based on an empirical null distribution due to strong correlation between genes (73, 74) was controlled at level α = 0.1. Venn diagrams were generated utilizing the InteractiVenn web-based tool (http://www.interactivenn.net/) (75), whereas individual gene overlap for identification of positive or negative correlations were performed in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

qPCR product synthesis was modeled as a function of the mouse study group using mixed effects models with random mouse effect to account for the correlation between repeated assays on the same mouse (51, 62, 63, 72). Significance was judged at the level α = 0.05 (2-sided). NanoString nCounter statistical analysis was performed on normalized gene expression levels in a manner similar to the approach for qPCR. Each gene was modeled as a function of the mouse study group using mixed effects models with random mouse effect (62, 63, 72). Significance was judged at the level α = 0.05 (2-sided).

RESULTS

A global assessment of the impact of MCS on gene expression within the septohippocampal circuit to understand the mechanistic effects of MCS during aging and in disease models has not been performed. We examined alterations in expression levels in Ts and 2N littermates within LCM-captured CA1 pyramidal neurons at 2 distinct time points, young mice at ∼6 mo old (prior to BFCN degeneration), and midaged mice at ∼11 mo old (following BFCN degeneration). We posit MCS changes in gene expression, independent of genotype or age, may underlie behavioral benefits seen in Ts and 2N mice (43, 45, 52). Further, we elucidate mechanistic pathways potentially driving the observed delay of age-related cognitive decline in both normal and cognitive degenerative models due to MCS delivery.

Results indicate gene expression levels were altered by MCS at both time points as a function of diet and genotype in each of the 22 GOCs assayed (Table 1). We examined the breakdown of each GOC to determine the genes affected by MCS treatment in both young adult (∼6-mo-old) and midaged (∼11-mo-old) mice stratified by genotype (Table 1). Specifically, we evaluated expression level differences as a function of diet and age. At both ages, gene level changes due to MCS in both genotypes did not differ significantly from each other, with 309 genes in Ts mice and 328 genes in 2N significantly changed (of 576 examined) in ∼6-mo-old mice and 459 genes in Ts mice and 464 genes in 2N significantly changed (of 648 examined) in ∼11-mo-old mice (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Gene expression level changes by MCS in 2N and Ts65Dn mice

| GOC | Young adult mice (∼6 mo old) |

Midaged mice (∼11 mo old) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes assayed (n) | 2N (P < 0.01) | 2N changed (%) | Ts65Dn (P < 0.01) | Ts65Dn changed (%) | Genes assayed (n) | 2N (P < 0.01) | 2N changed (%) | Ts65Dn (P < 0.01) | Ts65Dn changed (%) | |

| AD | 35 | 11 | 31.4 | 14 | 40.0 | 41 | 28 | 68.3 | 30 | 73.2 |

| CD, cell death | 33 | 19 | 57.6 | 15 | 45.5 | 34 | 23 | 67.6 | 23 | 67.6 |

| CH, channels | 24 | 16 | 66.7 | 18 | 75.0 | 24 | 18 | 75.0 | 16 | 66.7 |

| CYT, cytoskeleton | 35 | 19 | 54.3 | 17 | 48.6 | 36 | 23 | 63.9 | 22 | 61.1 |

| DV, development | 22 | 13 | 59.1 | 14 | 63.6 | 23 | 14 | 60.9 | 14 | 60.9 |

| ELAa | 50 | 26 | 52.0 | 28 | 56.0 | 50 | 35 | 70.0 | 36 | 72.0 |

| GABA, | 22 | 15 | 68.2 | 13 | 59.1 | 22 | 15 | 68.2 | 16 | 72.7 |

| GLIA, glial enriched genes | 11 | 5 | 45.5 | 5 | 45.5 | 11 | 6 | 54.5 | 7 | 63.6 |

| GLUC, glucose | 13 | 8 | 61.5 | 8 | 61.5 | 13 | 9 | 69.2 | 7 | 53.8 |

| GLUR, glutamate | 34 | 18 | 52.9 | 15 | 44.1 | 34 | 24 | 70.6 | 26 | 76.5 |

| GP, G-proteins | 33 | 22 | 66.7 | 25 | 75.8 | 33 | 20 | 60.6 | 21 | 63.6 |

| IE, immediate early genes | 7 | 4 | 57.1 | 5 | 71.4 | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 5 | 71.4 |

| MONO, monoamine | 45 | 31 | 68.9 | 24 | 53.3 | 45 | 39 | 86.7 | 40 | 88.9 |

| NT, neurotrophins | 19 | 7 | 36.8 | 9 | 47.4 | 20 | 14 | 70.0 | 12 | 60.0 |

| PEP, peptides | 16 | 9 | 56.3 | 4 | 25.0 | 18 | 15 | 83.3 | 16 | 88.9 |

| PP/K, phosphatase/kinase | 48 | 31 | 64.6 | 30 | 62.5 | 61 | 45 | 73.7 | 44 | 72.1 |

| PROT, proteases | 34 | 16 | 47.1 | 21 | 61.8 | 34 | 17 | 50.0 | 16 | 47.1 |

| SIRT, sirtuins | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 32 | 32 | 100.0 | 30 | 93.8 |

| SR, stress response | 7 | 2 | 28.6 | 3 | 42.9 | 22 | 20 | 90.9 | 17 | 77.3 |

| ST, steroids | 26 | 13 | 50.0 | 9 | 34.6 | 26 | 15 | 57.7 | 20 | 76.9 |

| SYN, synapse | 32 | 23 | 71.9 | 16 | 50.0 | 32 | 23 | 71.9 | 20 | 62.5 |

| TF, transcription factors | 29 | 20 | 69.0 | 16 | 55.2 | 30 | 23 | 76.7 | 21 | 70.0 |

| Totalb | 576 | 328 | 57.1 | 309 | 53.6 | 649 | 464 | 71.2 | 459 | 70.6 |

ELA endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy.

Totals for the number of genes assayed include the Bluescript vector (pBs), which is not in any GOC.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams of gene expression level changes within CA1 pyramidal neurons due to MCS in Ts mice and 2N littermates at ∼6 and 11 mo old. A) In ∼6-MO mice, 328 genes are differentially regulated because of MCS in 2N mice and 309 in Ts mice, with 220 genes overlapping between genotypes, of which 51.4% are down-regulated and 48.6% are up-regulated. Only 1 overlapping gene (0.04%) has an expression level change in the opposite direction (mismatch) between genotypes. B) Mice at ∼11 mo display larger numbers of MCS-responsive genes, with 464 differentially regulated in 2N mice and 459 in Ts mice, respectively, with 396 genes overlapping between genotypes, of which 35.4% are down-regulated and 63.4% are up-regulated. Only 5 overlapping genes (1.3%) were mismatched. Arrows indicate down-regulated and up-regulated gene percentages, respectively, with ≠ indicating the low gene percentages that are in the opposite direction.

The ∼6-mo-old cohort had approximately half of the genes queried significantly impacted by MCS in both disomic (328/576 genes; 57%) and trisomic (309/576 genes; 54%) mice compared with the normal choline diet cohort (Fig. 1A), and ∼70% of overlapping genes with significant expression level changes in both genotypes (220 genes, Fig. 1A and Table 1). MCS caused both up-regulation (106 genes; 48.6% in Ts and 2N) and down-regulation (113 genes; 51.4% in Ts and 2N) of select transcripts (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. S1A). Key differentially regulated transcripts (a full list of differentially regulated genes in both genotypes at ∼6 mo old is presented in Supplemental Table S1) included several endosomal-lysosomal genes, notably up-regulation of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (Lamp2), cathepsin G, cathepsin H, and sortilin 1 and down-regulation of Rab11b, cathepsin B (Ctsb), cathepsin E, and early endosome antigen 1. In contrast, several Ntf genes were up-regulated, including Ntf5 and Ntrk3, along with several Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A (GABAA) receptor subunits, including GABAA receptor subunit-α (Gabra) Gabra1, Gabra3, Gabra6, GABAA receptor subunit-β1, and GABAA receptor subunit-δ (Gabrd). Down-regulation was also observed in AD-related genes neprilysin (Nep) and β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1, whereas up-regulation of select synaptic-related markers including synaptosomal-associated protein 25 kDa (Snap25) and syntaxin 7 was found.

The ∼11-mo-old cohort (post-BFCN degeneration) showed significantly higher numbers of genes affected by MCS in both disomic (464/649 genes; 72%) and trisomic (459/649 genes; 71%) mice compared with the normal choline diet cohort, with ∼86% of overlapping genes displaying significant expression level changes (396 genes, Fig. 1B and Table 1). Similar to ∼6-mo-old animals, MCS caused both up-regulation (251 genes; 63.4% in Ts and 2N) and down-regulation (140 genes; 35.4% in Ts and 2N) in ∼11-mo-old mice (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. S1B). With 72 additional genes for the ∼11-mo-old cohort, many transcripts not queried in the younger cohort revealed gene expression level changes, including the neurodegeneration-associated genes A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain–containing proteins (ADAM) Adam9, Adam10, and Adam17, along with dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation–regulated kinases (Dyrk) Dyrk1a and Dyrk3. Select genes showing no changes in the ∼6-mo-old cohort but MCS responsiveness in the ∼11-mo-old cohort included the endosomal-lysosomal rab GTPases Rab5 and Rab7 and up-regulation of the Ntf brain-derived neurotrophic factor and Ntf3. Ntf5 was MCS-responsive in both the ∼6- and 11-mo-old cohorts. Additionally, several protein kinase transcripts not affected (2 of 3) or not queried (7 of 7) in the ∼6-mo-old cohort showed significant down-regulation by MCS in the ∼11-mo-old cohort. Differential gene expression profiles revealed that MCS had a stronger effect on aged animals (a full list of differentially regulated genes in both genotypes at ∼11 mo old is presented in Supplemental Table S2).

Because we were most interested in the lifelong effects of MCS treatment, we determined possible interactions between aging and maternal dietary treatment in the offspring. Accordingly, we curated genes altered by MCS by age in both genotypes. Analysis of genes from ∼6- to 11-mo-old mice revealed similar percentages of genes altered by MCS in both genotypes, with 231 genes (2N) and 213 genes (Ts) showing differential expression during aging and MCS (Fig. 2A, B). Unlike comparisons at both ages due to diet and genotype seen in Fig. 1, the mosaic of gene changes due to age fell into 2 distinct categories: up-regulation or down-regulation in both ∼6- and 11-mo-old mice (convergent expression) and divergent expression with either up-regulation in ∼6-mo-old mice and down-regulation in ∼11-mo mice or down-regulation in ∼6-mo-old mice and up-regulation in ∼11-mo-old mice (Fig. 2C). Convergently expressed genes displayed a similar differential regulation in 2N (77% up-regulation and 23% down-regulation; Fig. 2C and Supplemental Table S3) and Ts mice (68% up-regulation and 32% down-regulation; Fig. 2C and Supplemental Table S4). Moreover, 2N mice (49.8%) and Ts mice (58.7%) displayed a substantial number of genes with divergent expression levels (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 2.

Venn diagrams of gene expression level changes within CA1 pyramidal neurons due to MCS in Ts mice and 2N littermates by comparing ages. A) In 2N mice, 328 genes are differentially regulated by MCS in young, ∼6-mo-old mice, and 464 genes are differentially regulated by MCS in older ∼11-mo-old mice, with 231 overlapping between age points. However, 121 of these MCS-responsive gene changes occur in the same direction, whereas 110 of these MCS-responsive gene changes occur in the opposite directions during aging. B) In Ts mice, 309 genes are differentially regulated by MCS in young, ∼6-mo-old mice, and 459 genes are differentially regulated by MCS in older ∼11-mo-old mice, with 213 overlapping between age points. Similar to 2N mice, less than half (88) of these MCS-responsive gene changes occur in the same direction, whereas 125 of these MCS-responsive gene changes occur in the opposite directions during aging. C) Color-coded heatmaps illustrating relative expression changes in 2N (left panel) and Ts (right panel) mice that have convergent expression because of MCS and age (top portion of the panel) or divergent (mismatched) expression because of MCS and age (bottom portion of the panel). Arrows indicate down-regulated and up-regulated gene totals, respectively.

Convergently expressed genes impacted by MCS treatment regardless of age or genotype were of particular interest because these differentially regulated genes represent a population of MCS-responsive genes during the adult lifespan. We curated genes that displayed significant differences following MCS in relation to both age and genotype (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table S5). Although hundreds of genes showed significant expression level changes within the 4 genotypes or ages examined (∼6-mo-old Ts and 2N and ∼11-mo-old Ts and 2N; Figs. 1 and 2), 129 genes were significantly altered in all of the subsets (Supplemental Fig. S2 and Supplemental Table S5). Out of these 129 gene candidates, 53 genes, representing 9.2% of the ∼6-mo-old and 8.2% of the ∼11-mo-old total genes assayed, were changed in the same direction regardless of age or genotype (Fig. 4B and Table 2). We examined these 53 genes and observed that several key GOCs were highly represented, including GABAA receptors, endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy markers, monoamines, protein phosphatases and kinases, and transcription factors (Fig. 4A and Table 2). We posit these genes and the molecular pathways therein are likely to be key regulators of behavioral benefits previously shown by MCS treatment and are worthy of additional in-depth follow-up using a variety of molecular, cellular, and morphologic techniques.

Figure 3.

Illustration of gene expression level changes within CA1 pyramidal neurons. Genes that were changed by MCS in 2N ∼6-mo-old mice (purple; 328 genes) and 2N ∼11-mo-old mice (red; 464 genes), Ts ∼6-mo-old mice (green; 309 genes) and Ts ∼11-mo-old mice (yellow; 459 genes) are shown, with overlapping genes affected in multiple cohorts (age + MCS or genotype + MCS). Genes displaying MCS effects regardless of age or genotype are shown in the central overlap of 129 genes. Of these 129 genes, less than half (53) are altered by MCS in the same direction (See Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

Depiction of MCS-responsive genes within CA1 pyramidal neurons in relevant GOC pathways. A) Pie chart illustrating expression level changes driven by MCS independent of age and genotype by GOC. B) Color-coded heatmap of key MCS-responsive genes that display convergent gene expression changes. Of these 53 transcripts, 13 are significantly down-regulated by MCS, and 40 genes are significantly up-regulated by MCS independently of age or genotype.

TABLE 2.

Genes regulated by MCS independent of age and genotype

| Gene name | Gene description | GOC | Regulation by MCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCNG1 | cyclin G1 | CD | Up |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | CD | Down |

| KCNA1 | potassium voltage-gated channel A1 | CH | Down |

| KCNIP | Kv channel-interacting protein | CH | Up |

| AP1S1 | adaptor related protein complex 1 subunit-σ1 | CYT | Up |

| AFP | α-fetoprotein | DV | Up |

| ATG4B | autophagy-related 4B cysteine peptidase | ELA | Up |

| CTSB | cathepsin B | ELA | Down |

| LAMP2 | lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 | ELA | Up |

| MYO5B | myosin VB | ELA | Up |

| PPT1 | palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 | ELA | Up |

| RAB27 | RAB27, member RAS oncogene family | ELA | Up |

| GABRA1 | GABAA receptor-α1 subunit | GABA | Up |

| GABRA3 | GABAA receptor-α3 subunit | GABA | Up |

| GABRA6 | GABAA receptor-α6 subunit | GABA | Up |

| GABRB1 | GABAA receptor-β1 subunit | GABA | Up |

| GABRD | GABAA receptor-δ subunit | GABA | Up |

| SLC2A1 | solute carrier (glucose) 2A1 | GLUC | Up |

| GLRA3 | glycine receptor-α3 subunit | GLUR | Down |

| GRIK4 | glutamate receptor ionotropic kainate 4 | GLUR | Up |

| GNAT2 | G-protein subunit-α transducin 2 | GP | Up |

| ARC | activity regulated cytoskeleton associated protein | IE | Up |

| CART | cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript | MONO | Up |

| CHRM4 | cholinergic receptor muscarinic 4 | MONO | Down |

| CHRNA4 | cholinergic receptor nicotinic-α4 | MONO | Up |

| DRD5 | dopamine receptor D5 | MONO | Up |

| HTR2B | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2B | MONO | Up |

| MAOA | monoamine oxidase A | MONO | Up |

| MAOB | monoamine oxidase B | MONO | Up |

| PAM | peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase | MONO | Up |

| SLC18A3 | solute carrier 18A3; VACHT | MONO | Up |

| GDNF | glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor | NT | Up |

| IGF2 | IGF 2 | NT | Up |

| NTF5 | neurotrophin 5 | NT | Up |

| CAMK2A | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-IIα | PP/K | Down |

| FYN | FYN proto-oncogene kinase | PP/K | Down |

| ITPKC | inositol-trisphosphate 3-kinase C | PP/K | Down |

| MAPK1 | MAPK 1; ERK2 | PP/K | Down |

| MAPK8 | MAPK 8; JNK | PP/K | Down |

| PPP3CB | protein phosphatase 3 catalytic subunit β | PP/K | Down |

| MME | membrane metallo-endopeptidase; neprilysin | PROT | Down |

| PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | PROT | Up |

| DNAJC5 | DnaJ heat shock protein C5 | SR | Up |

| HSC70 | heat shock cognate 70 | SR | Up |

| NCOA3 | nuclear receptor coactivator 3 | ST | Up |

| NR3C1 | nuclear receptor 3C1; glucocorticoid receptor | ST | Up |

| NR4A3 | nuclear receptor 4A3 | ST | Up |

| SNAP25 | synaptosome-associated protein 25 | SYN | Up |

| AFF4 | AF4/FMR2 family member 4 | TF | Up |

| CREBBP | CREB binding protein | TF | Down |

| CREM | cAMP-responsive element modulator | TF | Up |

| ERCC1 | excision repair cross-complementing 1 | TF | Up |

| SUV39H1 | suppressor of variegation 3–9 1 | TF | Up |

CD, cell death; CH, channel; CYT, cytoskeleton; DV, development; ELA, endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy; GLUC, glucose; GLUR, glutamate; GP, G-protein; IE, immediate early gene; MONO, monoamine; NT, neurotrophin; PP/K, phosphatase/kinase; PROT, protease; SR, stress response; ST, steroid; SYN, synapse; TF, transcription factor

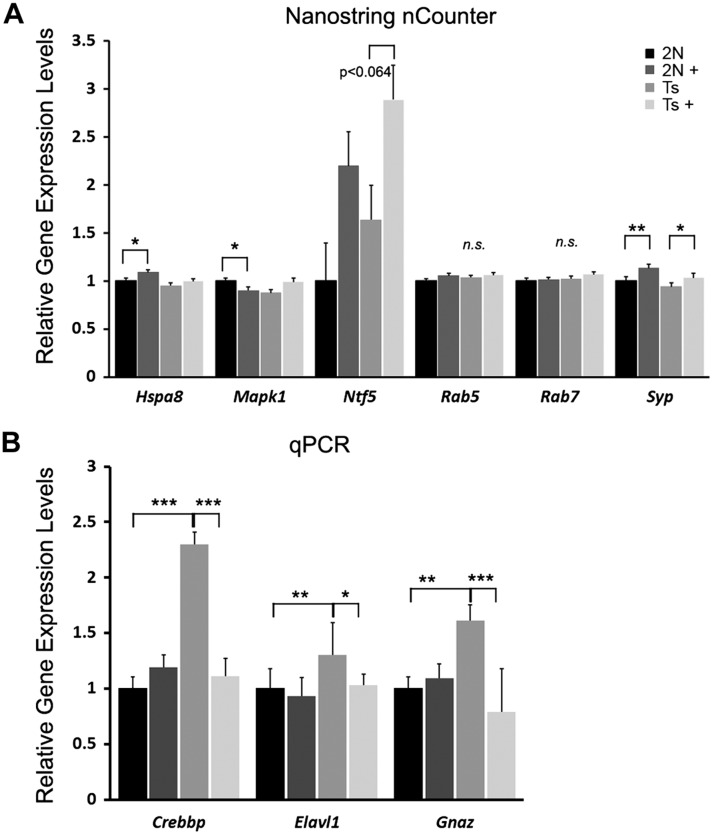

Validation of select transcripts at ∼6 mo old was performed by qPCR and by NanoString nCounter through CA1 subregional analysis and not single population analysis because single population analysis does not generate the RNA sample volume necessary for either qPCR or NanoString nCounter (51, 62, 63, 76–79). Subregional analysis by NanoString nCounter (the codeset is listed in Supplemental Table S6) revealed concurrent expression level changes in glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 4 (Gria4) and synaptophysin and trend-level changes in Ntf5 that matched the custom-designed microarray findings (Fig. 5A). NanoString nCounter for MAPK 1 (Mapk1) matched MCS Ts but not MCS 2N microarray findings, whereas NanoString nCounter for heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 8 (Hspa8) matched for MCS 2N but not MCS Ts microarray findings (Fig. 5A). Moreover, Rab5 and Rab7 did not show changes due to MCS in the ∼6-mo-old cohort by either microarray or NanoString nCounter (Fig. 5A). Several MCS-responsive genes observed by microarray analysis were not validated by NanoString nCounter, including Ctsb and the GABAA receptor subunit Gabra1, GABAA receptor subunit-β1, and Gabrd, likely because of the admixed tissue source for NanoString nCounter analysis (Fig. 5A). qPCR analysis of several genes showing MCS responsiveness in the ∼6-mo-old animals included Gnaz and Elavl1, which matched microarray findings (Fig. 5B). Similar to the NanoString nCounter results for Mapk1, Crebbp qPCR matched MCS Ts but not MCS 2N microarray findings (Fig. 5B). Validation in the ∼11-mo-old cohort by NanoString nCounter was similar to the results for Hspa8 in the ∼6-mo-old cohort because Gabrd (up-regulated) and Ctsb (down-regulated) matched for MCS 2N but not MCS Ts microarray findings (unpublished results). Because of constraints, including RNA quantity, availability, and cost considerations, not all genes showing MCS responsiveness by custom-designed microarray analysis could be feasibly analyzed by either NanoString nCounter or qPCR analyses.

Figure 5.

Validation of select expression level changes observed by single population microarray analysis in an independent cohort of ∼6-mo-old Ts and 2N mice. A) NanoString nCounter analysis corroborated microarray findings for Hspa8 and Mapk1 for 2N MCS-treated offspring and synaptophysin (Syp) for both 2N and Ts MCS-treated offspring, with a trend for Ntf5 gene expression from subregional CA1 dissections but no significant alterations in Rab5, and Rab7, confirming microarray findings. B) qPCR analysis validated Crebbp, Elavl1, and Gnaz custom-designed microarray observations because they were up-regulated in Ts mice and attenuated in Ts+ mice. Arrows indicate significant changes that are in the opposite direction of the single population microarray findings. N.s., nonsignificant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Through profiling single populations of vulnerable CA1 pyramidal neurons via LCM and custom-designed microarray analysis, we found profuse gene expression level changes in younger (∼6-mo-old) and midaged (∼11-mo-old) mice by MCS in Ts mice and their 2N littermates. This MCS treatment paradigm has previously been used for behavioral and septohippocampal immunohistological studies and has shown beneficial effects in both cognition and brain morphometry (42–45). Previous work by our group has shown a subset of genes with aberrant expression levels in trisomic mice that are reversed or attenuated by MCS (51). These observations parallel benefits of MCS in regards to hippocampal-dependent learning by both spatial recognition and attentional tasks in Ts65Dn mice (43, 45, 52). Herein, we examined underlying gene expression changes caused by MCS, which supersede genotypic gene changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons, a key component of the septohippocampal circuit. We found expression level mosaics are both overlapping and divergent, depending on genotype and age of the animals, indicating the complexity of gene regulation following early choline delivery. Individual genes can be tracked in the Supplemental Tables to verify their specific MCS responsiveness. Because there were literally hundreds of genes regulated by MCS, we chose to highlight those that were either up-regulated or down-regulated regardless of age or genotype (Supplemental Fig. S4).

To examine MCS-responsive genes, we curated results to find differentially regulated genes in each cohort (Supplemental Fig. S2 and Supplemental Table S5). Of these genes queried, 53 genes showed significant changes in expression due to MCS treatment regardless of age or genotype (Fig. 4B and Table 2), representing ∼8–9% of the total number of genes queried that persisted throughout adult life. A subset of these genes was represented in 5 GOC pathways: GABAA receptors, endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy, apoptosis, learning, memory and cognition, and protein phosphatase and kinase activity. From both a neurologic standpoint as well as an aging standpoint, the major causes of cellular dysfunction clearly relate to these pathways. We discuss several of the longitudinally MCS-responsive genes in the context of the circuitry of these 5 functional GOCs.

Patients with DS have documented GABAergic dysfunction, which results in impairments of synaptic plasticity and an imbalance of excitation and inhibition (80, 81). Trisomic mice mimic GABAergic dysfunction seen in human DS, including changes in subcellular localization of GABAA receptors away from the dendritic shaft to the spine neck and increases of GABA-evoked firing (81, 82). We demonstrated up-regulation of several GABAA receptor subunits, including α1, α3, α6, β1, and δ via MCS. Previous work has shown no changes in α1 and α3 immunoreactivity within the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice (81). However, we saw increases in both these subunit mRNAs by MCS, regardless of genotype or age. Notably, δ-subunit–containing GABAA receptors in the hippocampal CA1 region are mediated by picrotoxin, a potential treatment in DS for recovery of cognition and long-term potentiation (83), and have been shown to modulate slow-acting and tonic inhibitory currents, limiting the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons (84). The ability of MCS to increase expression of select GABAA receptor subunits may be critical for repairing the excitatory-inhibitory synaptic imbalance in DS, which is thought to impair synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory.

Several endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy genes were MCS-responsive, including endosomal-lysosomal markers Ctsb, Lamp2, palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (Ppt1), autophagy genes tumor protein p53 (Tp53), and autophagy-related 4B cysteine peptidase (Atg4b). Interestingly, Ctsb expression is down-regulated by MCS, and previous work has shown that knockout of Ctsb in an APP mouse model improves memory deficits (85, 86), which was linked to Aβ reduction (85, 87). Lamp2 expression is up-regulated by MCS, which is involved in fusing the lysosome to the autophagosome to facilitate autophagy (88). Lamp2 is decreased in AD apolipoprotein E4/E4 brains, potentially driving early onset AD pathology (89). Ppt1, which is up-regulated by MCS, has been linked to both endosomal dysfunction and increased apoptotic pathway activity in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (90). In PPT1 knockout or knockdown models, there is an increased level of cholesterol biosynthesis, postulating a role for Ppt1 in both lysosomal function and in lipid metabolism (91). MCS up-regulates Snap25, which promotes Snap receptor–mediated endocytosis (92–94). MCS also down-regulates Tp53, a multifunctional transcription factor shown to control autophagic function through up-regulation of AMPK and phosphatase and tensin homolog, inhibitors of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (95, 96). Atg4b is both partially regulated by Tp53 and up-regulated by MCS. Atg4b is localized to the autophagosome and is the cysteine protease of Lc3 (97, 98). The cleavage of Lc3 by Atg4b allows the Lc3 C-terminal fragment to conjugate to lipids within the autophagosome (98, 99). Collectively, these endosomal-lysosomal and autophagy gene expression changes provide a compelling argument for the lifelong beneficial effects of MCS toward AD-related pathology in this established DS-AD model.

Apoptotic function also appears to be impacted by MCS treatment because select prosurvival pathways are stimulated. This includes up-regulation of several genes [i.e., DnaJ heat shock protein family (heat shock protein 40) member C5, Ppt1, and Hspa8] whose encoded proteins interact with each other to promote cellular survival (90, 94, 100). Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 3, also up-regulated by MCS, is a known prosurvival gene (101, 102). Cellular stress and nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 3 (NR4a3) knockdown are also associated with increased apoptosis in hypoxic cells (101). Thus, MCS increased expression of negative regulators of apoptotic function, suggesting that MCS promotes a mechanism of neuroprotection through decreased cell death pathway activation and increased neuronal survival signaling.

Multiple genes associated with learning and memory are also impacted by MCS. These include down-regulation of muscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 (Chrm4), which plays a key regulatory role in the hippocampus for glutamatergic signaling and is dysregulated in schizophrenia (103). By contrast, solute carrier family 18 member A3 (Slc18a3), the vesicular acetylcholine transporter, is up-regulated by MCS and is associated with hippocampal-dependent learning. Decreased Slc18a3 signaling has deleterious effects on working memory and synaptic plasticity (104, 105). Likewise, Ntf5 is up-regulated by MCS, whereas decreases in the human homolog, Ntf4, have been previously shown by our group within CA1 pyramidal neurons in mild cognitive impairment and AD (106). Further, in Ntf4 and Ntf5 knockout mice, traumatic brain injury causes increased cell death, and reversal of Ntf4 and Ntf5 deficiency reduces cell loss (107). Snap25, in addition to its role in endocytosis, has a critical role in neurotransmission, neuromodulation, and memory formation (108, 109). Snap25 has altered expression in several neurodegenerative disorders, including AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and DS (109, 110). Nep is down-regulated by MCS, and Nep dysfunction increases toxic Aβ species, impairs synaptic plasticity, and increases cognitive abnormalities in an AD mouse model (111). Normalizing Nep expression by MCS may help to restore aberrant synaptic plasticity seen in DS and AD. Expression level changes due to MCS may underlie the beneficial effects seen on both hippocampal-dependent spatial and attentional tasks (3, 43–45, 52).

In several neurodegenerative disorders, multiple key regulators of kinase activity show aberrant increased expression, including Mapk1 (112, 113) and Mapk8 (114, 115). In MCS-treated offspring, expression levels of Mapk1 and Mapk8 were down-regulated, notably in midaged mice. These kinases are expressed as a consequence of cellular stress, and down-regulation by MCS may indicate attenuated cellular stress levels. Down-regulation of Crebbp was also observed following MCS, consistent with previous observations demonstrating aberrant Crebbp acetylation is associated with neurodegeneration in AD and Parkinson’s disease (116). Up-regulation of cAMP-responsive element modulator (Crem), a modulator of cAMP, has also been shown in the dentate gyrus in AD (117), a relatively spared hippocampal region in the AD brain. Crem up-regulation in a potentially resilient area may indicate a positive role for Crem in neuroprotection that is likewise seen in the hippocampus of MCS-treated offspring. Further, Fyn proto-oncogene (Fyn), a key molecule in AD pathology both in mediating the synaptotoxic effects of Aβ and in hyperphosphorylation of tau (118–120), was down-regulated by MCS. Fyn knockdown has also previously been shown to be neuroprotective (119, 121). Modulation of kinase and phosphatase activity is critical for normal neuronal function, and MCS may provide beneficial changes to key regulators of phosphatase and kinase pathways.

In summary, MCS provides lifelong benefits to DS mice and normal offspring littermates within a key hippocampal neuronal cell type. Gene expression changes were greater by diet (i.e., MCS) relative to aging and genotype, which is an uncommon finding. Positive benefits of MCS not only impact the behavioral profile of trisomic mice (3, 43–45, 52), but also affects the molecular profile of vulnerable cell populations in the brain, as seen here. Although this study was performed specifically examining RNA expression level changes due to MCS within a vulnerable hippocampal cell type, future studies examining changes in key encoded protein levels (at the regional level) and potentially in additional DS models, including the Dp16 model, await initiation. Demonstrated benefits of MCS in the established Ts65Dn model for gene expression of neuroprotective transcripts and reduction of apoptotic signaling as well as several other key GOC pathways within vulnerable CA1 pyramidal neurons indicate a profound need for choline during neurodevelopment, which has lifelong consequences for brain health. Accordingly, MCS studies in both human and mouse models have demonstrated the pressing need for choline supplementation in the developing brain (3, 11), and our single population analysis supports these contentions at the molecular and cellular level. Thus, current recommended levels of choline, in both cognitively normal and neurologic disease states, need to be further explored from translational and clinical trial perspectives, especially within cell types and circuits vulnerable to DS and AD pathology.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Arthur Saltzman at the Nathan Kline Institute for expert technical assistance. This study was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging Grants AG014449, AG043375, AG055328, and AG107617 and the Alzheimer’s Association. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 2N

normal disomic offspring

- 2N+

normal disomic maternal choline supplemented offspring

- Aβ

amyloid-β peptide

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain–containing protein

- Atg4b

autophagy-related 4B cysteine peptidase

- BFCN

basal forebrain cholinergic neuron

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- Crebbp

CREB binding protein

- Crem

cAMP-responsive element modulator

- Ctsb

cathepsin B

- DS

Down syndrome

- Dyrk

dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation–regulated kinase

- Elavl1

embryonic lethal, abnormal vision–like 1

- EST

expressed sequence-tagged cDNA

- Fyn

Fyn proto-oncogene kinase

- GABA

gamma aminobutyric acid

- Gabra

GABAA receptor subunit α

- Gabrd

GABAA receptor subunit-δ

- Gnaz

G-protein, α-z polypeptide

- GOC

gene ontology category

- Gria4

glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 4

- HSA21

human chromosome 21

- Hspa8

heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 8

- Lamp2

lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- MCS

maternal choline supplementation

- Nep

neprilysin

- Ntf

neurotrophin

- Ntrk1

neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1

- Ntrk2

neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- Ntrk3

neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 3

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PEMT

phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

- Ppt1

palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Slc18a3

solute carrier family 18 member A3

- Snap25

synaptosome-associated protein 25kDa

- TC

terminal continuation

- Tp53

tumor protein p53

- Ts

Ts65Dn, unsupplemented maternal choline offspring

- Ts+

Ts65Dn, maternal choline supplemented offspring

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M. J. Alldred, B. J. Strupp, and S. D. Ginsberg designed the research; M. J. Alldred, H. M. Chao, J. Beilin, and B. E. Powers performed the research; M. J. Alldred, H. M. Chao, S. H. Lee, E. Petkova, and S. D. Ginsberg analyzed data; and M. J. Alldred, H. M. Chao, and S. D. Ginsberg wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meck W. H., Smith R. A., Williams C. L. (1989) Organizational changes in cholinergic activity and enhanced visuospatial memory as a function of choline administered prenatally or postnatally or both. Behav. Neurosci. 103, 1234–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley C. M., Ash J. A., Powers B. E., Velazquez R., Alldred M. J., Ikonomovic M. D., Ginsberg S. D., Strupp B. J., Mufson E. J. (2016) Effects of maternal choline supplementation on the septohippocampal cholinergic system in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13, 84–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strupp B. J., Powers B. E., Velazquez R., Ash J. A., Kelley C. M., Alldred M. J., Strawderman M., Caudill M. A., Mufson E. J., Ginsberg S. D. (2016) Maternal choline supplementation: a potential prenatal treatment for Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeisel S. H., Klatt K. C., Caudill M. A. (2018) Choline. Adv. Nutr. 9, 58–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blusztajn J. K. (1998) Choline, a vital amine. Science 281, 794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blusztajn J. K., Mellott T. J. (2013) Neuroprotective actions of perinatal choline nutrition. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 51, 591–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan P. O., Meaney M. J., Szyf M. (2008) Diet and the epigenetic (re)programming of phenotypic differences in behavior. Brain Res. 1237, 12–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwan S. T. C., King J. H., Grenier J. K., Yan J., Jiang X., Roberson M. S., Caudill M. A. (2018) Maternal choline supplementation during normal murine pregnancy alters the placental epigenome: results of an exploratory study. Nutrients 10, E417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blusztajn J. K., Slack B. E., Mellott T. J. (2017) Neuroprotective actions of dietary choline. Nutrients 9, E815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan J., Ginsberg S. D., Powers B., Alldred M. J., Saltzman A., Strupp B. J., Caudill M. A. (2014) Maternal choline supplementation programs greater activity of the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) pathway in adult Ts65Dn trisomic mice. FASEB J. 28, 4312–4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caudill M. A., Strupp B. J., Muscalu L., Nevins J. E. H., Canfield R. L. (2018) Maternal choline supplementation during the third trimester of pregnancy improves infant information processing speed: a randomized, double-blind, controlled feeding study. FASEB J. 32, 2172–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davenport C., Yan J., Taesuwan S., Shields K., West A. A., Jiang X., Perry C. A., Malysheva O. V., Stabler S. P., Allen R. H., Caudill M. A. (2015) Choline intakes exceeding recommendations during human lactation improve breast milk choline content by increasing PEMT pathway metabolites. J. Nutr. Biochem. 26, 903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz A. B., Cohen V. V., Swersky C. C., Stover J., Vitiello G. A., Lovesky J., Chuang J. C., Shields K., Fomin V. G., Lopez Y. S., Mohan S., Ganti A., Carrier B., Malysheva O. V., Caudill M. A. (2017) Genetic variation in choline-metabolizing enzymes alters choline metabolism in young women consuming choline intakes meeting current recommendations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeisel S. H. (2013) Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of choline. Int. J. Womens Health 5, 193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwee M. C., Sim M. K. (1978) Free choline concentration and cephalin-N-methyltransferase activity in the maternal and foetal liver and placenta of pregnant rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 5, 649–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline (1998) Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin and Choline, National Academy Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross R. G., Hunter S. K., McCarthy L., Beuler J., Hutchison A. K., Wagner B. D., Leonard S., Stevens K. E., Freedman R. (2013) Perinatal choline effects on neonatal pathophysiology related to later schizophrenia risk. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 290–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson S. W., Carter R. C., Molteno C. D., Meintjes E. M., Senekal M. S., Lindinger N. M., Dodge N. C., Zeisel S. H., Duggan C. P., Jacobson J. L. (2018) Feasibility and acceptability of maternal choline supplementation in heavy drinking pregnant women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 42, 1315–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson S. W., Carter R. C., Molteno C. D., Stanton M. E., Herbert J. S., Lindinger N. M., Lewis C. E., Dodge N. C., Hoyme H. E., Zeisel S. H., Meintjes E. M., Duggan C. P., Jacobson J. L. (2018) Efficacy of maternal choline supplementation during pregnancy in mitigating adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and cognitive function: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 42, 1327–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheatham C. L., Goldman B. D., Fischer L. M., da Costa K. A., Reznick J. S., Zeisel S. H. (2012) Phosphatidylcholine supplementation in pregnant women consuming moderate-choline diets does not enhance infant cognitive function: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 96, 1465–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cataldo A. M., Peterhoff C. M., Troncoso J. C., Gomez-Isla T., Hyman B. T., Nixon R. A. (2000) Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartley D., Blumenthal T., Carrillo M., DiPaolo G., Esralew L., Gardiner K., Granholm A. C., Iqbal K., Krams M., Lemere C., Lott I., Mobley W., Ness S., Nixon R., Potter H., Reeves R., Sabbagh M., Silverman W., Tycko B., Whitten M., Wisniewski T. (2015) Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: common pathways, common goals. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 700–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartley S. L., Handen B. L., Devenny D. A., Hardison R., Mihaila I., Price J. C., Cohen A. D., Klunk W. E., Mailick M. R., Johnson S. C., Christian B. T. (2014) Cognitive functioning in relation to brain amyloid-β in healthy adults with Down syndrome. Brain 137, 2556–2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leverenz J. B., Raskind M. A. (1998) Early amyloid deposition in the medial temporal lobe of young Down syndrome patients: a regional quantitative analysis. Exp. Neurol. 150, 296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann D. M., Yates P. O., Marcyniuk B., Ravindra C. R. (1986) The topography of plaques and tangles in Down’s syndrome patients of different ages. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 12, 447–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sendera T. J., Ma S. Y., Jaffar S., Kozlowski P. B., Kordower J. H., Mawal Y., Saragovi H. U., Mufson E. J. (2000) Reduction in TrkA-immunoreactive neurons is not associated with an overexpression of galaninergic fibers within the nucleus basalis in Down’s syndrome. J. Neurochem. 74, 1185–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wisniewski K. E., Dalton A. J., McLachlan C., Wen G. Y., Wisniewski H. M. (1985) Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome: clinicopathologic studies. Neurology 35, 957–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai F., Williams R. S. (1989) A prospective study of Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome. Arch. Neurol. 46, 849–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta M., Dhanasekaran A. R., Gardiner K. J. (2016) Mouse models of Down syndrome: gene content and consequences. Mamm. Genome 27, 538–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamlett E. D., Boger H. A., Ledreux A., Kelley C. M., Mufson E. J., Falangola M. F., Guilfoyle D. N., Nixon R. A., Patterson D., Duval N., Granholm A. C. (2016) Cognitive impairment, neuroimaging, and Alzheimer neuropathology in mouse models of Down syndrome. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 13, 35–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardiner K., Fortna A., Bechtel L., Davisson M. T. (2003) Mouse models of Down syndrome: how useful can they be? Comparison of the gene content of human chromosome 21 with orthologous mouse genomic regions. Gene 318, 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturgeon X., Gardiner K. J. (2011) Transcript catalogs of human chromosome 21 and orthologous chimpanzee and mouse regions. Mamm. Genome 22, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holtzman D. M., Santucci D., Kilbridge J., Chua-Couzens J., Fontana D. J., Daniels S. E., Johnson R. M., Chen K., Sun Y., Carlson E., Alleva E., Epstein C. J., Mobley W. C. (1996) Developmental abnormalities and age-related neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13333–13338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Insausti A. M., Megías M., Crespo D., Cruz-Orive L. M., Dierssen M., Vallina I. F., Insausti R., Flórez J. (1998) Hippocampal volume and neuronal number in Ts65Dn mice: a murine model of Down syndrome. Neurosci. Lett. 253, 175–178; erratum: 258:190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurt M. A., Davies D. C., Kidd M., Dierssen M., Flórez J. (2000) Synaptic deficit in the temporal cortex of partial trisomy 16 (Ts65Dn) mice. Brain Res. 858, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granholm A. C., Sanders L., Seo H., Lin L., Ford K., Isacson O. (2003) Estrogen alters amyloid precursor protein as well as dendritic and cholinergic markers in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Hippocampus 13, 905–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saran N. G., Pletcher M. T., Natale J. E., Cheng Y., Reeves R. H. (2003) Global disruption of the cerebellar transcriptome in a Down syndrome mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2013–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belichenko P. V., Kleschevnikov A. M., Masliah E., Wu C., Takimoto-Kimura R., Salehi A., Mobley W. C. (2009) Excitatory-inhibitory relationship in the fascia dentata in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol. 512, 453–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belichenko P. V., Masliah E., Kleschevnikov A. M., Villar A. J., Epstein C. J., Salehi A., Mobley W. C. (2004) Synaptic structural abnormalities in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down Syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol. 480, 281–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley C. M., Powers B. E., Velazquez R., Ash J. A., Ginsberg S. D., Strupp B. J., Mufson E. J. (2014) Maternal choline supplementation differentially alters the basal forebrain cholinergic system of young-adult Ts65Dn and disomic mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 1390–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Granholm A. C., Sanders L. A., Crnic L. S. (2000) Loss of cholinergic phenotype in basal forebrain coincides with cognitive decline in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. Exp. Neurol. 161, 647–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon J., Chen M., Gandhy S. U., Strawderman M., Levitsky D. A., Maclean K. N., Strupp B. J. (2010) Perinatal choline supplementation improves cognitive functioning and emotion regulation in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Behav. Neurosci. 124, 346–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powers B. E., Kelley C. M., Velazquez R., Ash J. A., Strawderman M. S., Alldred M. J., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Strupp B. J. (2017) Maternal choline supplementation in a mouse model of Down syndrome: effects on attention and nucleus basalis/substantia innominata neuron morphology in adult offspring. Neuroscience 340, 501–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ash J. A., Velazquez R., Kelley C. M., Powers B. E., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Strupp B. J. (2014) Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial mapping and increases basal forebrain cholinergic neuron number and size in aged Ts65Dn mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 70, 32–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Velazquez R., Ash J. A., Powers B. E., Kelley C. M., Strawderman M., Luscher Z. I., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Strupp B. J. (2013) Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial learning and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 58, 92–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelley C. M., Powers B. E., Velazquez R., Ash J. A., Ginsberg S. D., Strupp B. J., Mufson E. J. (2014) Sex differences in the cholinergic basal forebrain in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 24, 33–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mellott T. J., Williams C. L., Meck W. H., Blusztajn J. K. (2004) Prenatal choline supplementation advances hippocampal development and enhances MAPK and CREB activation. FASEB J. 18, 545–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Napoli I., Blusztajn J. K., Mellott T. J. (2008) Prenatal choline supplementation in rats increases the expression of IGF2 and its receptor IGF2R and enhances IGF2-induced acetylcholine release in hippocampus and frontal cortex. Brain Res. 1237, 124–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mellott T. J., Kowall N. W., Lopez-Coviella I., Blusztajn J. K. (2007) Prenatal choline deficiency increases choline transporter expression in the septum and hippocampus during postnatal development and in adulthood in rats. Brain Res. 1151, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandstrom N. J., Loy R., Williams C. L. (2002) Prenatal choline supplementation increases NGF levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of young and adult rats. Brain Res. 947, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alldred M. J., Chao H. M., Lee S. H., Beilin J., Powers B. E., Petkova E., Strupp B. J., Ginsberg S. D. (2018) CA1 pyramidal neuron gene expression mosaics in the Ts65Dn murine model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease following maternal choline supplementation. Hippocampus 28, 251–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powers B. E., Velazquez R., Kelley C. M., Ash J. A., Strawderman M. S., Alldred M. J., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Strupp B. J. (2016) Attentional function and basal forebrain cholinergic neuron morphology during aging in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 4337–4352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Detopoulou P., Panagiotakos D. B., Antonopoulou S., Pitsavos C., Stefanadis C. (2008) Dietary choline and betaine intakes in relation to concentrations of inflammatory markers in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 424–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duchon A., Raveau M., Chevalier C., Nalesso V., Sharp A. J., Herault Y. (2011) Identification of the translocation breakpoints in the Ts65Dn and Ts1Cje mouse lines: relevance for modeling Down syndrome. Mamm. Genome 22, 674–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alldred M. J., Duff K. E., Ginsberg S. D. (2012) Microarray analysis of CA1 pyramidal neurons in a mouse model of tauopathy reveals progressive synaptic dysfunction. Neurobiol. Dis. 45, 751–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ginsberg S. D. (2005) Glutamatergic neurotransmission expression profiling in the mouse hippocampus after perforant-path transection. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 13, 1052–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ginsberg S. D. (2010) Alterations in discrete glutamate receptor subunits in adult mouse dentate gyrus granule cells following perforant path transection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 397, 3349–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alldred M. J., Che S., Ginsberg S. D. (2008) Terminal continuation (TC) RNA amplification enables expression profiling using minute RNA input obtained from mouse brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9, 2091–2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alldred M. J., Che S., Ginsberg S. D. (2009) Terminal continuation (TC) RNA amplification without second strand synthesis. J. Neurosci. Methods 177, 381–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Che S., Ginsberg S. D. (2004) Amplification of RNA transcripts using terminal continuation. Lab. Invest. 84, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ginsberg S. D. (2008) Transcriptional profiling of small samples in the central nervous system. Methods Mol. Biol. 439, 147–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alldred M. J., Lee S. H., Petkova E., Ginsberg S. D. (2015) Expression profile analysis of vulnerable CA1 pyramidal neurons in young-middle-aged Ts65Dn mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 523, 61–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alldred M. J., Lee S. H., Petkova E., Ginsberg S. D. (2015) Expression profile analysis of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in aged Ts65Dn mice, a model of Down syndrome (DS) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 2983–2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ginsberg S. D. (2005) RNA amplification strategies for small sample populations. Methods 37, 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ginsberg S. D., Alldred M. J., Counts S. E., Cataldo A. M., Neve R. L., Jiang Y., Wuu J., Chao M. V., Mufson E. J., Nixon R. A., Che S. (2010) Microarray analysis of hippocampal CA1 neurons implicates early endosomal dysfunction during Alzheimer’s disease progression. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 885–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ginsberg S. D., Che S., Wuu J., Counts S. E., Mufson E. J. (2006) Down regulation of trk but not p75NTR gene expression in single cholinergic basal forebrain neurons mark the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 97, 475–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang Y., Mullaney K. A., Peterhoff C. M., Che S., Schmidt S. D., Boyer-Boiteau A., Ginsberg S. D., Cataldo A. M., Mathews P. M., Nixon R. A. (2010) Alzheimer’s-related endosome dysfunction in Down syndrome is Abeta-independent but requires APP and is reversed by BACE-1 inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1630–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Applied Biosystems (2004) Guide to performing relative quantitation of gene expression using real-time quantitative PCR. Applied biosystems product guide, 1-60. Available at: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/cms_042380.pdf

- 69.Nanostring nCounter (2017) nCounter expression data analysis guide, MAN-C0011-04. Available at: https://www.nanostring.com/download_file/view/251/3779

- 70.Ginsberg S. D. (2014) Considerations in the use of microarrays for analysis of the CNS. In Reference Module in Biomedical Research, pp. 1-7, Elsevier, New York [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer M. J., Dolgalev I., Alldred M. J., Heguy A., Ginsberg S. D. (2015) Calorie restriction suppresses age-dependent hippocampal transcriptional signatures. PLoS One 10, e0133923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCulloch C. E., Searle S. R., Neuhaus J. M. (2011) Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 73.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Efron B. (2007) Correlation and large-scale simultaneous significance testing. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 102, 93–103 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heberle H., Meirelles G. V., da Silva F. R., Telles G. P., Minghim R. (2015) InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics 16, 169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Counts S. E., He B., Che S., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J. (2008) Galanin hyperinnervation upregulates choline acetyltransferase expression in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 5, 228–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Counts S. E., He B., Che S., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J. (2009) Galanin fiber hyperinnervation preserves neuroprotective gene expression in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 18, 885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ginsberg S. D., Alldred M. J., Gunnam S. M., Schiroli C., Lee S. H., Morgello S., Fischer T. (2018) Expression profiling suggests microglial impairment in human immunodeficiency virus neuropathogenesis. Ann. Neurol. 83, 406–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Veldman-Jones M. H., Brant R., Rooney C., Geh C., Emery H., Harbron C. G., Wappett M., Sharpe A., Dymond M., Barrett J. C., Harrington E. A., Marshall G. (2015) Evaluating robustness and sensitivity of the NanoString technologies nCounter platform to enable multiplexed gene expression analysis of clinical samples. Cancer Res. 75, 2587–2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Araujo B. H., Torres L. B., Guilhoto L. M. (2015) Cerebal overinhibition could be the basis for the high prevalence of epilepsy in persons with Down syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 53, 120–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Contestabile A., Magara S., Cancedda L. (2017) The GABAergic hypothesis for cognitive disabilities in Down syndrome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11, 54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deidda G., Parrini M., Naskar S., Bozarth I. F., Contestabile A., Cancedda L. (2015) Reversing excitatory GABAAR signaling restores synaptic plasticity and memory in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Nat. Med. 21, 318–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fernandez F., Morishita W., Zuniga E., Nguyen J., Blank M., Malenka R. C., Garner C. C. (2007) Pharmacotherapy for cognitive impairment in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 411–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee V., Maguire J. (2014) The impact of tonic GABA-A receptor-mediated inhibition on neuronal excitability varies across brain region and cell type. Front. Neural Circuits 8, 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kindy M. S., Yu J., Zhu H., El-Amouri S. S., Hook V., Hook G. R. (2012) Deletion of the cathepsin B gene improves memory deficits in a transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model expressing AβPP containing the wild-type β-secretase site sequence. J. Alzheimers Dis. 29, 827–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun B., Zhou Y., Halabisky B., Lo I., Cho S. H., Mueller-Steiner S., Devidze N., Wang X., Grubb A., Gan L. (2008) Cystatin C-cathepsin B axis regulates amyloid beta levels and associated neuronal deficits in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 60, 247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hook G., Yu J., Toneff T., Kindy M., Hook V. (2014) Brain pyroglutamate amyloid-β is produced by cathepsin B and is reduced by the cysteine protease inhibitor E64d, representing a potential Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic. J. Alzheimers Dis. 41, 129–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ghavami S., Shojaei S., Yeganeh B., Ande S. R., Jangamreddy J. R., Mehrpour M., Christoffersson J., Chaabane W., Moghadam A. R., Kashani H. H., Hashemi M., Owji A. A., Łos M. J. (2014) Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 112, 24–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Parcon P. A., Balasubramaniam M., Ayyadevara S., Jones R. A., Liu L., Shmookler Reis R. J., Barger S. W., Mrak R. E., Griffin W. S. T. (2018) Apolipoprotein E4 inhibits autophagy gene products through direct, specific binding to CLEAR motifs. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 230–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Henderson M. X., Wirak G. S., Zhang Y. Q., Dai F., Ginsberg S. D., Dolzhanskaya N., Staropoli J. F., Nijssen P. C., Lam T. T., Roth A. F., Davis N. G., Dawson G., Velinov M., Chandra S. S. (2016) Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis with DNAJC5/CSPα mutation has PPT1 pathology and exhibit aberrant protein palmitoylation. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 621–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kollmann K., Uusi-Rauva K., Scifo E., Tyynelä J., Jalanko A., Braulke T. (2013) Cell biology and function of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-related proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832, 1866–1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burré J., Sharma M., Tsetsenis T., Buchman V., Etherton M. R., Südhof T. C. (2010) Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sharma M., Burré J., Bronk P., Zhang Y., Xu W., Südhof T. C. (2012) CSPα knockout causes neurodegeneration by impairing SNAP-25 function. EMBO J. 31, 829–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharma M., Burré J., Südhof T. C. (2011) CSPα promotes SNARE-complex assembly by chaperoning SNAP-25 during synaptic activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 30–39; erratum: 182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Feng Y., He D., Yao Z., Klionsky D. J. (2014) The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 24, 24–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maiuri M. C., Galluzzi L., Morselli E., Kepp O., Malik S. A., Kroemer G. (2010) Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Oshitani-Okamoto S., Ohsumi Y., Yoshimori T. (2004) LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2805–2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang Z., Wilkie-Grantham R. P., Yanagi T., Shu C. W., Matsuzawa S., Reed J. C. (2015) ATG4B (autophagin-1) phosphorylation modulates autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 26549–26561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang L., Li J., Ouyang L., Liu B., Cheng Y. (2016) Unraveling the roles of Atg4 proteases from autophagy modulation to targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 373, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fontaine S. N., Zheng D., Sabbagh J. J., Martin M. D., Chaput D., Darling A., Trotter J. H., Stothert A. R., Nordhues B. A., Lussier A., Baker J., Shelton L., Kahn M., Blair L. J., Stevens S. M., Jr., Dickey C. A. (2016) DnaJ/Hsc70 chaperone complexes control the extracellular release of neurodegenerative-associated proteins. EMBO J. 35, 1537–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]