Abstract

Giant cell tumor of bone is a benign, primary skeletal neoplasm that has an unpredictable pattern of biologic aggressiveness, and cytogenetically demonstrates genetic instability by exhibiting telomeric associations. Molecular analysis of telomeres from giant cell tumor of bone demonstrated reduction of telomere length (average loss of 500 base pairs) in eight individuals when compared with their leukocyte DNA. Those tumors which exhibited telomeric associations were found to have a greater reduction in telomere length than tumors not exhibiting them. For comparison, eleven cytogenetically healthy control individuals (7 females and 4 males, age range 2 weeks to 70 years) were included in this study. They demonstrated loss of telomere size (average 40 base pairs per year) with advancing age and the greatest rate of telomere reduction was identified in the young. Thus, the functional consequences of telomere shortening in a neoplastic cell may prove fundamental to sustaining the transformed phenotype in giant cell tumor of bone.

INTRODUCTION

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCT) is a primary skeletal neoplasm which demonstrates a high rate of local recurrence after surgical resection and exhibits the ability of benign pulmonary metastases in about two percent of patients [1, 2, 3]. It typically occurs in the ends of long bones around major joints in young adults. Wide surgical resections performed in an attempt to lower the recurrence rate often necessitates compromising musculoskeletal performance and function.

Cytogenetic analyses of GCT have repeatedly demonstrated telomeric associations (tas) [4–14]. This rare cytogenetic phenomenon represents the fusion of the termini of chromosomes. In our experience with 20 GCT patients, approximately 10–30% of tumor cells examined showed tas in 12 of the 20 patients. In a recent study and review of literature by Bridge et al. [11], 48 of 66 GCT specimens (75%) exhibited tas. The demonstration of telomeric association in GCT supports the hypothesis of chromosomal instability in tumorigenesis.

The telomere is that region of DNA at the end of a linear chromosome required for replication and stability of the chromosome. DNA at the terminal ends of all chromosomes have a special structure to avoid binding to the ends of DNA from other chromosomes, thus preventing end-to-end fusions or tas. Telomeric DNA consists of terminal repeat arrays (TRAs) of base pairs characterized by clusters of G residues in the 3’ strand (TTAGGG)n and have been isolated from telomeres in humans [15, 16]. TRAs are highly conserved in nature and are found in the termini of linear chromosomes from plants, animals, protists and fungi [17].

Reduction in telomere length has been identified during the in vitro senescence of human fibroblasts [18]. The maintenance of telomeric integrity is fundamental for a fibroblast to repeatedly undergo mitosis and for a neoplastic cell to propagate its transformed phenotype. We hypothesize that molecular changes in the telomeres of chromosomes from GCT are present and speculate about their contribution to genetic instability and oncogenesis. As an external control, we explored the molecular structure of the telomere in the aging process of healthy individuals to compare rates of telomere reduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor samples were obtained intraoperatively from eight patients (4 males and 4 females: age range 12 to 53 years) with histopathologically confirmed GCT and tumor cell cultures immediately established following routine protocols [9]. Concomitant peripheral blood samples were also obtained from each GCT subject as an internal control. No patient had pulmonary metastasis, preoperative radiation or chemotherapy. Four patients (50%) had tas observed cytogenetically from short term cultured tumor cells (less than 6 weeks) but no chromosomal abnormalities were identified in their leukocytes. Clinical and cytogenetic data of patients with giant cell tumor of bone are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and cytogenetic data on patients with giant cell tumor of bone

| Patient | Lanesa | Age (years) | Gender | Tumor location | No. of cells examined | Telomeres involved in tasb (No. of occurrences) | Other abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–2 | 23 | F | Scapula | 20 | 3p(1), 11q(1), 13q(l), 17p(2), 19p(1), 20q(2) | 1–double ring |

| 2 | 3–4 | 25 | F | Proximal tibia | 15 | None | None |

| 3 | 5–6 | 39 | M | Proximal tibia | 25 | None | None |

| 4 | 7–8 | 53 | M | Distal femur | 30 | 5p(1), 5q(2), 6p(1), 11p(1), 13q(1), 14q(5), 17q(1), 19q(1), 20q(1), 21q(3), 22q(1) | 1–double ring 1–double minute 1–acrocentric marker 2–4N cells |

| 5 | 9–10 | 40 | F | Proximal tibia | 60 | 2q(1), 10p(2), 19q(1), 20p(1), Xq(1) | 1–acrocentric marker 1–ring 13 2–ring 17 1–ring 20 5–4N cells 1–8N cell |

| 6 | 11–12 | 12 | F | Sacrum | 100 | None | 2–4N cells |

| 7 | 13–14 | 20 | M | Distal femur | 47 | 11q(1), 12p(1), 14p(1), 15p(1), 16p(3), 16q(2), 18p(1), 19p(1), 19q(1), 20p(1), 20q(1), 21p(2), 21q(1), 22p(2), 22q(1) | 2–monosomy 22 2–markers 7–4N cells |

| 8 | 15–16 | 47 | M | Distal femur | 27 | None | None |

Numbers correspond to lanes seen in Figure 1.

tas = telomeric association.

Isolation of human telomeric DNA is accomplished using the restriction enzyme, HinfI, which does not cut within the repeat telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n [19]. Quantitative Southern hybridization was performed following established protocols [6, 19] comparing tumor DNA to internal control leukocyte DNA in dual lanes from the same patient using a 32P radiolabeled (TTAGGG)50 telomeric probe synthesized by polymerase chain reaction and commercially available from Oncor, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD).

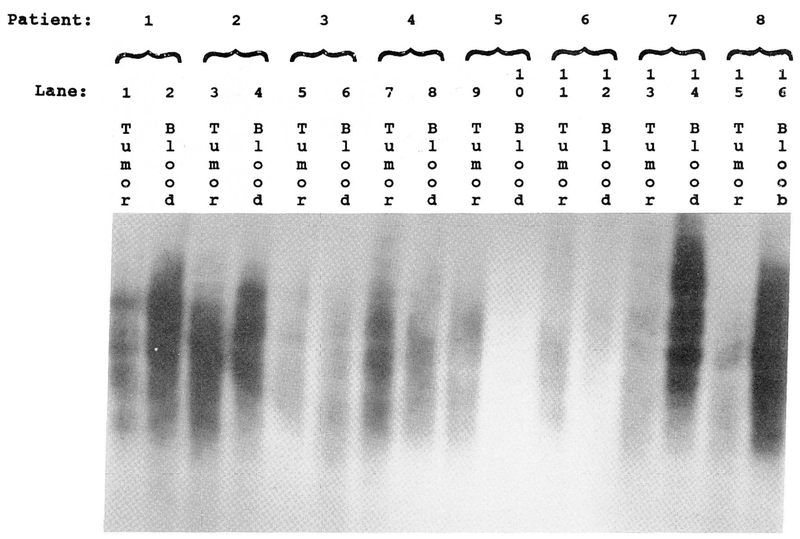

Genomic DNA was isolated from GCT cells cultured for less than six weeks and from peripheral blood samples following standard protocols [6, 19]. Five micrograms of DNA was digested from each sample with HinfI, at 37°C for four hours. A minigel electrophoresis was performed to check for completeness of digestion. DNA was then loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel and electrophoresis performed for five hours at 58 volts. The gel was then blotted to Gene Screen Plus nylon membrane and hybridized with the 32P-nick-labeled (TTAGGG)50 telomeric probe. Hybridization was performed at 42°C for two days and the filter washed in an SSC/SDS mixture at 42°C. The filters were then exposed to high performance autoradiographic film. The exposed autoradiographs were analyzed using an LBK soft laser spectrophotometer to determine the maximum DNA peak, length of hybridization signal, and the total area under the DNA absorption curve (Fig. 1). Peak intensity and migration distance were then analyzed from DNA isolated from both GCT and leukocytes on each patient. DNA fragments migrating farther, as detected by the hybridized radio-labeled telomere probe, represented shortened telomeres (telomeric reduction). GCT DNA expressing tas was also compared with tumors not demonstrating tas.

Figure 1.

Southern hybridization analysis of the telomere region in giant cell tumor of bone paired with leukocyte DNA from the same patient (5 μg per lane). DNA from smaller telomere regions migrate farther by electrophoresis and thus show a longer signal length. Tumor DNA shows significantly increased telomere reduction when compared to leukocyte (blood) DNA from the same patient.

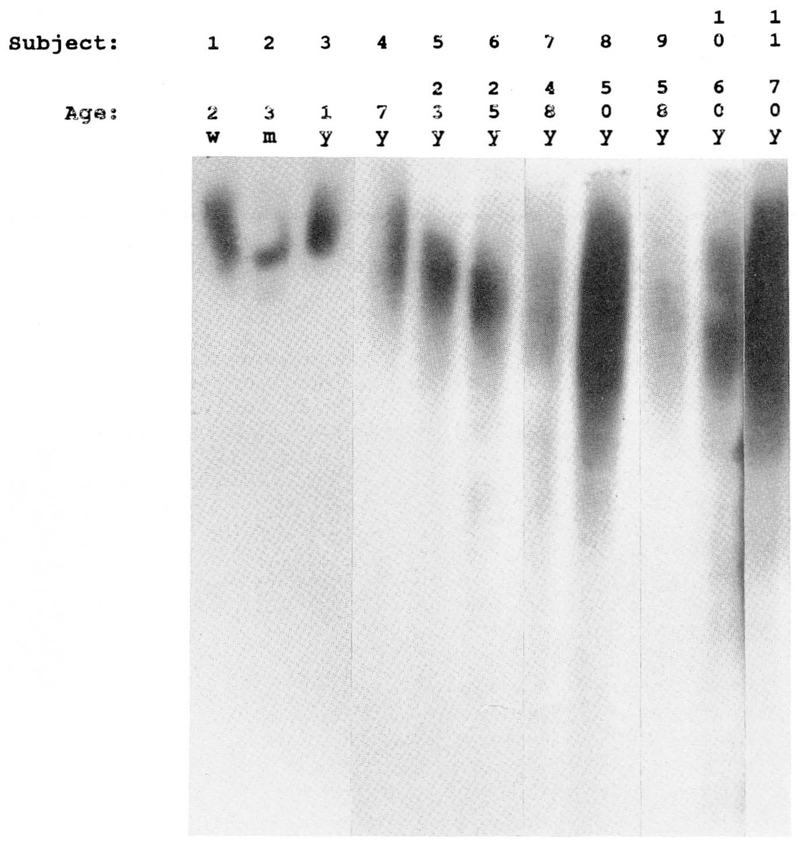

In addition, telomeric reduction as a function of aging was examined in DNA isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes of 11 healthy control subjects (7 females, 4 males) ranging in age from 2 weeks to 70 years. Using similar methodology, quantitative Southern hybridization with the radiolabeled telomeric probe was utilized in this external control aging study (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Southern hybridization analysis of the telomere region in 11 healthy controls with age ranging from 2 weeks (far left) to 70 years (far right). As the age of the subject increases, the length of the telomere decreases (with an average loss of 40 base pairs per year) thus a longer migration pattern is observed.

RESULTS

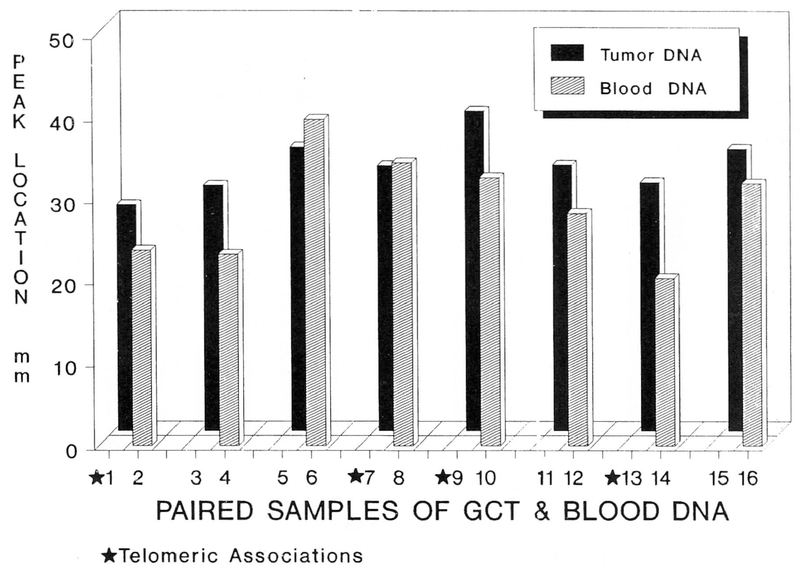

Autoradiographs of the radiolabeled hybridized filters were densitometrically scanned producing peaks for each DNA lane. Peak migration distance was calculated from each DNA lane. Graphic representation of the GCT Southern blot is illustrated in Figure 3. Optical density recorded by the scanner signifies radio-labeled probe hybridization at a known kilobase (kb) migration distance. The kb migration length was established using markers of known size. A mean peak intensity was calculated for each of the eight patient’s tumor DNA and leukocyte DNA. Tumor DNA from the eight GCT patients showed more telomeric reduction in the tumor DNA than that observed in DNA isolated from their respective leukocytes [using DNA densitometry peak location, tumor DNA showed significantly greater telomere reduction (matched t-test = −1.91, p < 0.05; one-tailed test)] than leukocyte (blood) DNA from the same patient (tumor DNA mean = 32.7 mm ± 1.2 (S.E.M.); blood DNA mean = 29.3 mm ± 2.2 (S.E.M.)]. Peak density determination of the DNA lanes indicates an average estimated decrease of 500 base pairs in telomeric length for the tumor DNA as compared with DNA from blood in the same patient (p < 0.05; independent t-test).

Figure 3.

Telomere migration in 8 patients with GCT. Paired samples of GCT and leukocyte (blood) DNA from each patient. Telomere reduction is significantly greater in GCT versus blood from the same patient in 6 of 8 patients. Numbers on the horizontal axis represent lanes as seen in Figure 1.

In order to examine for molecular telomere differences in patients with tas and those without tas, we divided the patients into two groups. The first group consisted of four patients (age 20, 23, 40, and 53 years) whose tumor DNA exhibited cytogenetic telomeric associations, while the second group contained four patients (age 12, 25, 39 and 47 years) who did not show tas. Interestingly, the patients with telomeric associations showed more of a reduction in telomeric size (625 fewer base pairs) but not statistically different when compared with patients not expressing telomeric associations (400 fewer base pairs).

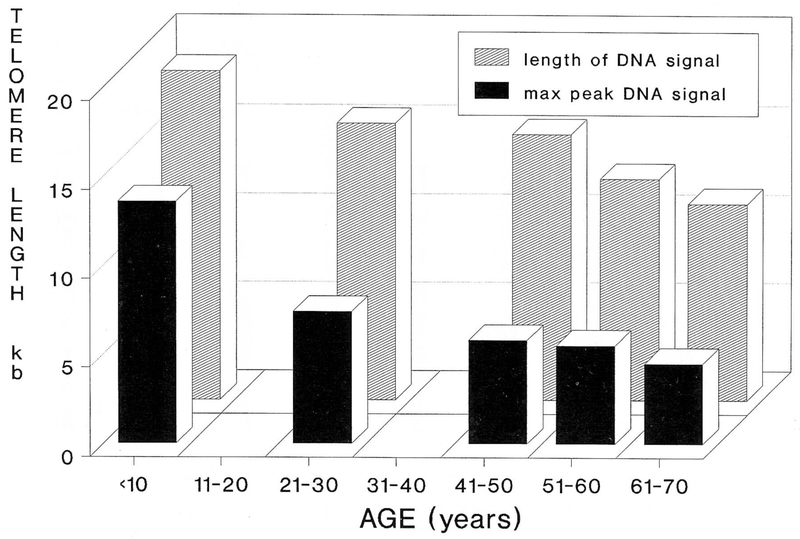

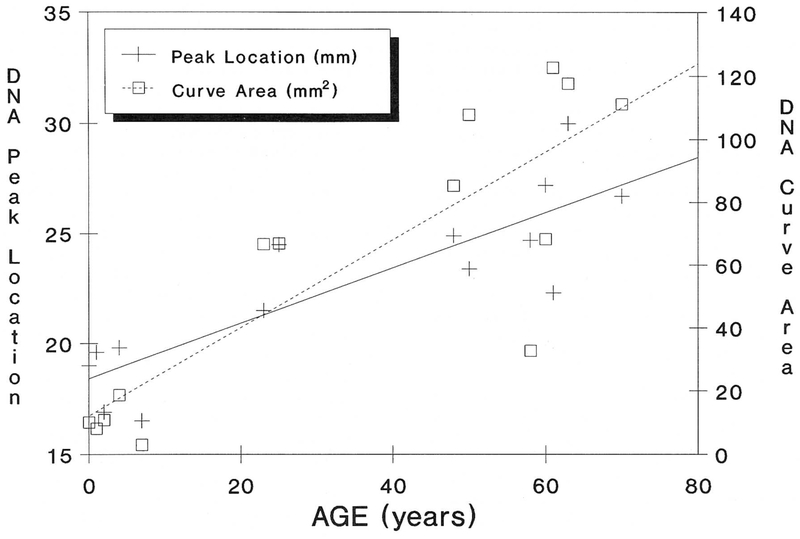

Telomere reduction with advancing age in healthy control individuals was also identified. Figure 4 illustrates telomere length averaged by decade while Figure 5 demonstrates the relationship of TRA migration length as a function of aging. The TRA distance was plotted as a function of age. Our data indicates a decrease in telomere size with advancing age and a significant Spearman rank correlation value of 0.69 (p < 0.05; one-tailed test). The slope of the regression line indicates a loss of 40 base pairs per year from the telomere region (from individuals 23 to 70 years of age). Our data supports previously reported telomeric aging studies of a loss of 33 base pairs per year [19]. Interestingly, this loss increases to 77 base pairs per year when younger patients (<20 years of age) are analyzed; thus, a greater rate of telomere reduction in younger individuals.

Figure 4.

Mean size estimates of telomere length in kb per decade determined by both length of DNA hybridization signal and maximum peak of the DNA signal. Advancing age results in a decrease in telomere size. The rate of the telomere reduction is greater in younger individuals.

Figure 5.

Both maximum DNA peak location and curve area demonstrate increased migration and greater telomere reduction (degradation) with age. The best fitting line was produced by regression analysis. Spearman rank correlation values were 0.69 (p < 0.05; one-tailed test) for both peak location and curve area.

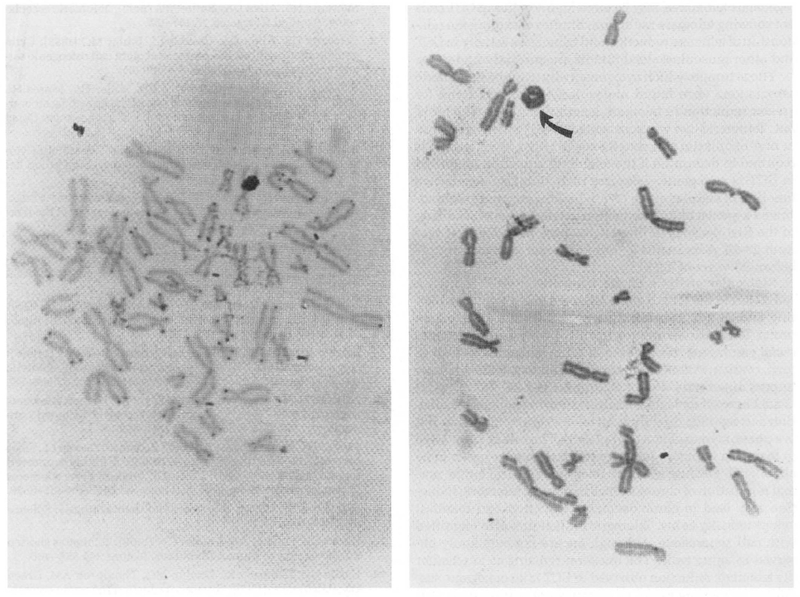

In situ hybridization using a commercially available biotin-labeled all human telomere probe (TTAGGG)n from Oncor, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD) produces a signal at the distal end of each human chromatid. This probe has been used to detect terminal deletions of abnormal chromosomes.

Slides containing metaphase spreads from control fibroblasts and tumor cells from GCT patients were treated and hybridized with the biotin-labeled all telomere probe. Hybridization of the probe was for 16 hours at 37°C in a humidified chamber and detection of probe hybridization was achieved through a series of treatments involving enzymatic conjugation and visualization using a light microscope after staining with Giemsa following manufacturers’ protocols (Oncor, Inc.). Standardization was undertaken on ten control fibroblast cultures and tumor cultures established from six GCT patients and cells analyzed by the same experienced technician. Over 300 metaphases were examined from both GCT cells and control fibroblasts grown in identical culture conditions. Representative metaphases from control fibroblasts and GCT cells showing the hybridization signal with all human telomere probe are shown in Figure 6. The hybridization signal was visually analyzed from the telomere region and was easily observed in control fibroblasts but decreased in GCT cells. This subjective observation is consistent with a decrease in telomere size; thus, a reduction in the in situ hybridization signal.

Figure 6.

Light in situ hybridization using a biotin-labeled telomere probe on both GCT and control fibroblasts. The signal from the telomere region is easily observed on most chromosomes in control fibroblasts (left), but absent or decreased on most chromosomes in GCT (right). Arrow designates a ring chromosome.

DISCUSSION

GCT is a unique tumor characterized by variable biologic aggressiveness. It is overtly benign in some patients but may aggressively spread in others. Histologically, its stromal cells and syncytial giant cells do not possess sufficient atypia to be classified as malignant. This benign cytological appearance masquerades its true aggressive clinical behavior which manifests as a high local recurrence rate and a two percent rate of benign pulmonary metastases. Histologic grading systems, histopathologic correlative studies, and flow cytometry have failed to differentiate clinically aggressive from non-aggressive subtypes [20–25]. A more sensitive marker system, such as that provided by cytogenetics or molecular analyses, is required before an understanding and prediction of biological aggressiveness for this neoplasm are determined.

In our study, telomere reduction was identified in six of eight patients with GCT and was significantly different from internal and external controls. Thus, not all GCT patients exhibited telomeric reduction when compared with controls. More research is needed to account for the lack of difference between DNA peak migration distance for tumor and blood DNA of the two GCT patients (one with tas and one without tas) not showing a reduction in the size of the telomere.

Recently, Nurnberg et al. [26] reported that among 60 intracranial tumors 42% showed telomere elongation, 22% showed telomere reduction and 37% exhibited equal lengths of the telomeres when compared with the patient’s peripheral blood leukocytes. Thus, there appears to be variability in telomere size in cells from different intracranial tumors. Similarly, we found that 25% of our GCT tumors did not show telomere reduction compared with their leukocyte DNA. Possibly, telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein enzyme needed to regenerate telomeres, may be more highly active in GCT cells not showing telomere reduction. Studies to explore the relationship of telomere reduction and telomerase activity in GCT and other musculoskeletal tumors are currently underway.

Those tumors which cytogenetically exhibited telomeric associations were found molecularly to show a trend for greater reduction in telomere length than those which did not. Telomeric loss was accelerated in GCT when compared to non-neoplastic cell senescence. Further investigation is required to determine if the telomeric reduction identified in GCT is oncogenic. Telomere reduction also occurs as a function of cellular aging [27], which in our study, demonstrated a greater annual reduction in telomere size occurring in the first decades of life (i.e., 40 base pairs loss per year from 23–70 years versus 77 base pairs per year for controls before 20 years of age).

Molecular analysis of the telomere in GCT showed a reduction in the length of the telomere using Southern blotting and in situ hybridization of the all human telomere probe. Telomeric shortening has also been observed in colorectal carcinoma, blast phase of acute leukemia, as well as lung, ovarian, Wilms’ and intracranial tumors, although these tumors apparently do not exhibit tas [19, 26, 28]. Thus, it is not known if molecular analysis showing telomeric reduction corresponds directly with telomeric association or if it is a phenomenon of most neoplasms. The role of telomerase to maintain telomere integrity in these tumors needs to be elucidated. Because telomere integrity is critical for the normal replication of chromosomes in mitosis, telomeric reduction may lead to chromosomal dysfunction and manifest cytogenetically as tas. Telomeric reduction is also identified with cell senescence, although tas are not commonly observed in aging cells. The question remains as to whether the telomeric reduction observed in GCT is an oncogenic sustaining or inciting event, or an artifact of culture time. Cellular aging, telomerase activity and additional chromosome in situ hybridization studies of the telomere region in GCT cells are underway. Determining the functional effects on the cell of telomere reduction may prove fundamental to understanding its relationship to tumorigenesis and normal cell growth and division.

Acknowledgments

Aided by the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Orthopedic Research & Educational Foundation Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanesa A (1987): Giant cell tumor of bone. JBJS 69A:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald DJ, Sim FH, McLeod RA, Dahlin DC (1986): Giant cell tumor of bone. JBJS 68A: 235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rock MG, Pritchard DJ, Unni KK (1984): Metastases from histologically benign giant cell tumor of bone. JBJS 66A:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardi G, Pandis N, Mandahl N, Heim J, Sfikas K, Willen H, Parragiotopoulos G, Rydholm A, Mitelman F (1991): Chromosome abnormalities in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 57:161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridge JA, Neff JR, Bhatia PS, Sanger WG, Murphy MD (1990): Cytogenetic findings and biologic behavior of giant cell tumors of bone. Cancer 65:2697–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler MG, Dahir GA, Schwartz HS (1993): Molecular analysis of transforming growth factor beta in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet, 66:108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz HS, Allen GA, Butler MG (1990): Telomeric associations. Applied Cytogenet 16:133–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz HS, Allen GA, Chudoba I, Butler MG (1992): Cytogenetic abnormalities in a rare case of giant cell osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 58:60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz HS, Butler MG, Jenkins RB, Miller DA, Moses HL (1991): Telomeric associations and consistent growth factor over-expression detected in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 56:263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz HS, Jenkins RB, Dahl RJ, Dewald GW (1989): Cytogenetic analyses on giant cell tumor of bone. Clin Orthop Rel Res 240:250–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridge JA, Neff JR, Mouron BS (1992): Giant cell tumor of bone. Chromosomal analysis of 48 specimens and review of the literature. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 58:2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguera R, Llombart-Bofch A, Lopez-Gines C, Carda C, Fernandez CI (1989): Giant cell tumor of bone, stage II, displaying translocation t(12;19)(q13;q13). Virchows Archive A Pathol Anat 415:377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su CC, Tzeng CC, Chow NH, Lin CJ (1991): Tissue culture, DNA flow cytometric and cytogenetic studies of a giant cell tumor of bone. Chin Med J 48:419–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dewald GW, Dahl RJ, Spurbeck JL, Carney JA, Gordon H (1987): Chromosomally abnormal clones and non-random telomeric translocations in cardiac myxomas. Mayo Clin Proc 62:558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allshire RC, Dempster M, Hastie ND (1989): Human telomeres contain at least three types of G-rich repeats distributed non-randomly. Nucleic Acids Res 17:4611–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moyzis RK, Buckingham JM, Cram LS, Dani M, Deaven LL, Jones MD, Meyne J, Ratliff RF, Wu J-R (1988): A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:6622–6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackburn EH (1990): Telomeres and their synthesis. Science 249:489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW (1990): Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345:458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hastie ND, Dempster M, Dunlop MG, Thompson AM, Green DK, Allshire RC (1990): Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with aging. Nature 346:866–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukunaga M, Nikaido T, Shimoda T, Ushigome S, Nakomori K (1992): A flow cytometric DNA analysis of giant cell tumors of bone including two cases with malignant transformation. Cancer 70:1886–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helio H, Karaharju E, Nordling S (1985): Flow cytometric determination of DNA content in malignant and benign bone tumors. Cytometry 6:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreicbergs A, Silvfersward C, Tribukait B (1984): Flow DNA analysis of primary bone tumors. Relationship between cellular DNA content and histopathologic classification. Cancer 53:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mankin HJ, Connor JF, Schiller AL, Perlmutter N, Alho A, McGuire M (1985): Grading of bone tumors by analysis of nuclear DNA content using flow cytometry. JBJS 67A:404–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Present D, Bertoni F, Hudson T, Enneking WF (1986): The correlation between the radiologic staging studies and histopathologic findings in aggressive stage 3 giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer 57:237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiang JH, Spanier SS, Benson NA, Braylan RC (1987): Flow cytometric analysis of DNA in hone and soft tissue tumors using nuclear suspensions. Cancer 59:1951–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nurnberg P, Thiel G, Weber F, Epplen JT (1993): Changes of telomere lengths in human intracranial tumors. Hum Genet 91:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsey J, McGill NI, Lindsey LA, Green DK, Cooke HJ (1991): In vivo loss of telomeric repeats with age in humans. Mutat Res 256:45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamson DJA, King DJ, Haites NE (1992): Significant telomere shortening in childhood leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 61:204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]