Abstract

Background

Although COPD affects both men and women, its prevalence is increasing more rapidly in women. Disease outcomes appear different among women with more frequent dyspnea and anxiety or depression but whether this translates into a different prognosis remains to be determined. Our aim was to assess whether the greater clinical impact of COPD in women was associated with differences in 3-year mortality rates.

Methods

In the French Initiatives BPCO real-world cohort, 177 women were matched up to 458 menon age (within 5-year intervals) and FEV1 (within 5% predicted intervals). 3-year mortality rate and survival were analyzed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

For a given age and level of airflow obstruction, women with COPD had more severe dyspnea, lower BMI, and were more likely to exhibit anxiety. Nevertheless, three-year mortality rate was comparable among men and women, respectively 11.2 and 10.8%. In a multivariate model, the only factors significantly associated with mortality were dyspnea and malnutrition but not gender.

Conclusion

Although women with COPD experience higher levels of dyspnea and anxiety than men at comparable levels of age and FEV1, these differences do not translate into variations in 3-year mortality rates.

Trial registration

04–479.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Survival, Gender differences

Background

Influence of gender on COPD expression and outcomes is an area of sustained interest [1, 2]. Although COPD affects both men and women, its prevalence is increasing more rapidly in women, particularly in younger women [1]. Women are more likely to be misdiagnosed [3], whereas there is increasing evidence suggesting gender-related differences in COPD risk. For example, female smokers are at greater risk of airflow obstruction than male smokers [4]. Disease progression and outcomes appear different among women and men with COPD [5, 6]. Younger women with COPD have a greater likelihood of more severe dyspnea and airflow limitation, and exhibit a higher risk of exacerbations [7, 8]. In COPD populations, several longitudinal studies showed an association between higher levels of symptoms and poorer prognosis [9]. Of interest, studies have found discrepant results regarding the relationship between gender and survival [10].

As shown in other studies [10, 11], previous analysis of the Initiatives BPCO cohort found that women suffer from higher levels of dyspnea and anxiety even after matching on age and FEV1 [12]. Whether these gender-related differences in symptoms translate into differences in survival remains unknown. Our aim was to assess whether the greater clinical impact of COPD in women was associated with differences in 3-year mortality rates.

Methods

As previously described, Initiatives BPCO is a rolling cohort of patients with COPD followed at French University Hospitals [13]. The primary aim of the cohort was to study COPD phenotypes, as previously reported [13]. The following data are collected as part of routine practice at inclusion: demographic and anthropometric characteristics, occupational exposures, smoking history, chronic bronchitis, exacerbation frequency, dyspnea assessed by mMRC dyspnea scale, health status, physician diagnosed comorbidities (asthma, rhinitis, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes, mechanical limitation, psychological status), medications and post-bronchodilator spirometry (FEV1, FVC).

Men and women were matched up to 3:1 on age (within 5-year intervals) and FEV1 (within 5% predicted intervals) leading to a small loss of sample size. Three-year mortality rate and survival were analyzed using logistic regression and Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test, respectively. Univariate comparisons between matched men and women were performed by chi2 and t-test. To identify which risk factors play a critical role as determinants of mortality in the studied population, we performed a multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis with the following tested covariates: cumulative smoking, chronic bronchitis, mMRC grade, FEV1% predicted, exacerbation history during the year prior to inclusion, allergic rhinitis, associated asthma, nutritional status, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, left heart failure, diabetes, sleep apnea syndrome and age. Data are provided as median [Q1 – Q3] or n (%), as appropriate.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Versailles (France), trial registration #04–479, and all subjects provided informed written consent.

Results

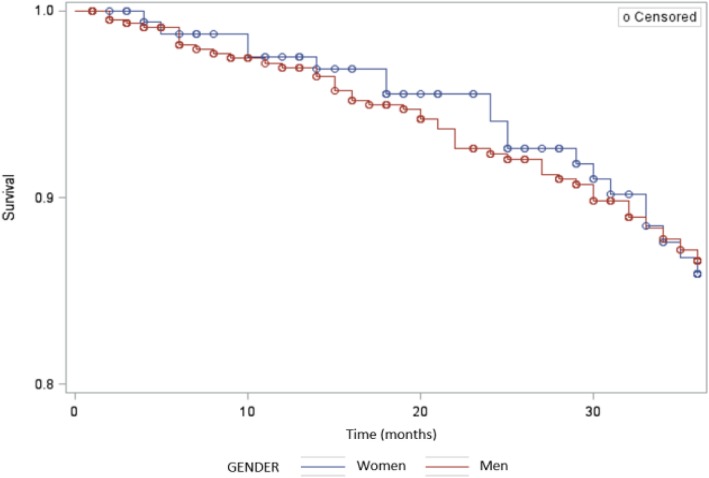

Among 954 patients (226 women) with COPD included at the time of the analyses, 177 women were matched to 458 men. Unmatched (non-included) women did not differ from matched (included) ones except for age and FEV1, which were the matching criteria (data not shown). Median values of age and percent predicted (pp) FEV1 were 63 years and 53%, respectively. Women had lower body mass index (BMI), higher mMRC dyspnea grade, resulting in a higher BOD (BMI, airflow obstruction, dyspnea) index, and a greater proportion of anxiety (defined by a hospital anxiety-depression-A subscore≥10). Rhinitis was more frequent in women, while coronary heart disease and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome were less frequent in women (Table 1). Three-year mortality rates were 11.2% in men and 10.8% in women with no significant difference (OR for men vs. women 0.9; 95% confidence interval [0.5–1.7]). Age at death was 68 years in men and 72 years in women with no significant difference. Survival was also comparable (Log-rank p = 0.9724, Fig. 1). In multivariate analysis, mortality was independently associated with only malnutrition (p = 0.02) and mMRC (p = 0.03), with cumulative smoking being retained in the model although of borderline significance (p = 0.06). Conversely, gender was not retained (p = 0.68).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studied population and univariate comparisons between age- and FEV1-matched (3:1 ratio) men (n = 458) and women (n = 177)

| Variables | Women | Men | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 177 | 458 | |

| Age (years) | 62 [56–70] | 63 [57–71] | 0.4171 |

| BMI | 23.2 [20.2–27.1] | 25.5 [22.1–29.0] | < 0.0001 |

| Malnutrition (BMI < 18 kg/m2) | 25 (14.1%) | 31 (6.8%) | 0.003 |

| Smoking (Pack-years) | 38.0 [24.8–57.0] | 41 [27–56] | 0.4080 |

| FEV1 (%) | 54 [37–69] | 53 [36–67] | 0.4257 |

| Number of moderate to severe exacerbations in the previous year | 1 [0–3] | 1 [0–2] | 0.1209 |

| mMRC | 2 [1–3] | 1 [1–2] | 0.0014 |

| mMRC ≥ 2 | 100 (56.5%) | 212 (46.3%) | 0.021 |

| BOD index | 3 [1–4] | 2 [1–4] | 0.0831 |

| SGRQ | 46 [32–57] a | 43 [28–59] a | 0.5776 |

| Asthma history | 28 (15.8%) | 52 (11.4%) | 0.128 |

| Rhinitis | 29 (16.4%) | 42 (9.2%) | 0.010 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 118 (66.7%) | 302 (65.9%) | 0.862 |

| Hypertension | 59 (33.3%) | 159 (34.7%) | 0.742 |

| Left heart failure | 16 (9%) | 54 (11.8%) | 0.321 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 11 (6.2%) | 79 (17.2%) | 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (9%) | 58 (12.7%) | 0.202 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 4 (2.3%) | 40 (8.7%) | 0.004 |

| HAD total score | 15 [11–21] b | 12 [8–17] b | < 0.0001 |

| Anxiety HAD A ≥ 10 | 65 (44.5%)b | 92 (27.6%)b | 0.0001 |

| Depression HAD D ≥ 10 | 34 (23.6%)b | 59 (17.7%)b | 0.136 |

| 3-year mortality | 19 (10.8%) | 51 (11.2%) | 0.896 |

| Age at death | 72 [66–79] | 68 [63–76] | 0.1691 |

BMI body mass index, HAD hospital anxiety and depression scale, mMRC modified medical respiratory council, SGRQ Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Data are provided as median [Q1 – Q3] or n (%), as appropriate

aMissing data for SGRQ, n = 28 in women, n = 116 in men

bMissing data for HAD scores: n = 33 in women, n = 131 in men

Fig. 1.

Survival according to gender, Kaplan Meier analysis, women in blue, men in red

Discussion

Several studies have been performed to assess gender-related differences in COPD expression and many found more severe manifestations of the disease in women [6, 10]. Some studies suggest that women with chronic bronchitis have significantly worse survival [14] whereas others have demonstrated that survival does not vary among men and women in smaller cohorts [15]. In a previous analysis of the Initiatives BPCO cohort, for a given age and level of airflow obstruction, women with COPD had higher BOD (BMI, airflow obstruction, dyspnea) scores due to greater dyspnea and lower BMI, suggesting the possibility of worse prognosis in women. However, the present data showed no difference in survival between men and women matched for age and ppFEV1, both in univariate analyses. Furthermore, even after multivariate analyses confirming a link between worse prognosis, malnutrition and breathlessness, in accordance to BODE, gender was neither validated. Similar findings were reported in the TORCH study, in which the risk of death was similar among men and women once analyses were adjusted for differences in baseline confounders [10]. Previous data comparing 265 women and 272 men with COPD matched using BODE score have shown that all-cause mortality was higher in males than females. However, women and men were not matched on age and women were significantly younger (63 vs 67 years, p < 0.001) [16]. Even if this age difference is small, it can have an influence on mortality. To exclude this bias, men and women were matched on age in our study.

One limitation of this study is the relatively short-term survival analysis and the absence of available data regarding specific causes of mortality, which prevents from analyzing whether some specific mortality rates differ between men and women. Our results suggest that differences between men and women in prognostic scores (here, the BOD score) and burden of symptoms (exacerbation number and dyspnea) do not translate into higher mortality in women. Finally, as in other studies [2, 6, 12], male gender was associated with a more frequent history of cardiovascular disease (here, ischemic heart disease), maybe explaining why the risk of mortality is similar among men and women despite women exhibiting more symptoms.

Conclusion

In the present study, COPD expression differed between men and women, with women experiencing more dyspnea and anxiety, and less diagnosed coronary heart disease and sleep apnea. These differences did not translate into significant differences in 3-year mortality rates and survival.

Acknowledgements

We thank the initiatives BPCO study group P.R.Burgel (Paris), G. Deslee (Reims), P. Surpas (Charnay), O. Le Rouzic (Lille), T.Perez (Lille), N. Roche (Paris), G. Brinchault-Rabin (Rennes), D. Caillaud (Clermont-Ferrand), P. Chanez (Marseille), I. Court-Fortune (Saint-Etienne), R. Escamilla (Toulouse), G. Jebrak (Paris), P.Nesme-Meyer (Lyon), M. Zysman (Nancy), C. Pinet (Toulon) and Brigitte Risse (ARAIRLOR, Association régionale d’aide aux insuffisants respiratoires de Lorraine, Nancy).

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FEV1

Forced Expiratory volume in one second

- GOLD

Global initiative for obstructive lung disease

- HAD

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

- mMRC

Modified Medical Research Council

- OSAS

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

Authors’ contributions

Every author made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; has given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

The Initiatives BPCO cohort is supported by Boehringer Ingelheim France since its creation and has been funded by Pfizer until 2015, in the form of unrestricted grant. The sponsors fund the database, statistical analyses, meetings and submission fees when required. They do not participate in decisions regarding collected data, analyses, article writing and submission. For all these aspects, the Initiatives BPCO group works in total independence.

An abstract describing the results presented here was presented at ERS International Congress 2018 Paris/France, and published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Versailles Saint Quentin University, authorization number 04–479, for protection of human beings involved in biomedical research. The study has also been approved by CCTIRS (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé), on the 6th January, 2005 (04–479). All patients provided written consent.

Consent for publication

All patients provided written consent. All authors provided consent to publication.

Competing interests

MZ reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Chiesi, and personal fees from GSK outside the submitted work.

PRB reports personal fees from Aptalis, personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Vertex, personal fees from Zambon, outside the submitted work.

ICF reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work.

GBR reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, outside the submitted work.

PNM reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from NOVARTIS, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, outside the submitted work.

PS reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work.

GD reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from BTG/PneumRx, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work.

TP reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work.

OLR reports grants and personal fees personal fees and non-financial support from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Lilly and Novartis; non-financial support from Glaxo Smith Kline, MundiPharma, Pfizer, Teva, Santelys Association, Vertex and Vitalaire, all outside the submitted work.

GJ reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Menarini, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Chiesi, outside the submitted work.

PC reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from ALK, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees and non-financial support from SNCF, outside the submitted work.

JLP reports grants from iBPCO association, during the conduct of the study.

DC has nothing to disclose.

NRreports grants and personal fees from Boehringe rIngelheim, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Mundipharma, personal fees from Cipla, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Sandoz, personal fees from 3 M, personal fees from Zambon, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maeva Zysman, Phone: +33.6.17.25.87.93, Email: maeva55@club-internet.fr.

on behalf of the Initiatives BPCO scientific committee and investigators:

P. R. Burgel, G. Deslee, P. Surpas, O. Le Rouzic, T. Perez, N. Roche, G. Brinchault-Rabin, D. Caillaud, P. Chanez, I. Court-Fortune, R. Escamilla, G. Jebrak, P. Nesme-Meyer, M. Zysman, C. Pinet, and Brigitte Risse

References

- 1.Jenkins CR, Chapman KR, Donohue JF, Roche N, Tsiligianni I, Han MK. Improving the management of COPD in women. Chest. 2017;151:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han MK, Arteaga-Solis E, Blenis J, Bourjeily G, Clegg DJ, DeMeo D, et al. Female sex and gender in lung/sleep health and disease. Increased understanding of basic biological, pathophysiological, and behavioral mechanisms leading to better health for female patients with lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:850–858. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0168WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman KR, Tashkin DP, Pye DJ. Gender bias in the diagnosis of COPD. Chest. 2001;119:1691–1695. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral AFS, Strachan DP, Burney PGJ, Jarvis DL. Female smokers are at greater. Risk of airflow obstruction than male smokers. UK biobank. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1226–1235. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1545OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naberan K, Azpeitia A, Cantoni J, Miravitlles M. Impairment of quality of life in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2012;106:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raherison C, Tillie-Leblond I, Prudhomme A, Taillé C, Biron E, Nocent-Ejnaini C, et al. Clinical characteristics and quality of life in women with COPD: an observational study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMeo DL, Ramagopalan S, Kavati A, Vegesna A, Han MK, Yadao A, et al. COPDGene investigators. Women manifest more severe COPD symptoms across the life course. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3021–3029. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S160270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aryal S, Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. Influence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1145–1154.12. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S54476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, Oga T, on Behalf of the Kansai COPD Registry and Research Group in Japan Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-yearsurvival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002;121:1434–1440. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celli B, Vestbo J, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Ferguson GT, Calverley PM, et al. Investigators of the TORCH Study. Sex differences in mortality and clinical expressions of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The TORCH experience. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:317–322. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0665OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Marco F, Verga M, Reggente M, Maria Casanova F, Santus P, Blasi F, et al. Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severity. Respir Med. 2006;100:1767–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche N, Deslée G, Caillaud D, Brinchault G, Court-Fortune I, Nesme-Meyer P, Surpas P, Escamilla R, Perez T, Chanez P, Pinet C, Jebrak G, Paillasseur JL, Burgel PR, INITIATIVES BPCO Scientific Committee Impact of gender on COPD expression in a real-life cohort. Respir Res. 2014;15:20. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgel PR, Paillasseur JL, Caillaud D, Tillie-Leblond I, Chanez P, Escamilla R, Court-Fortune I, Perez T, Carré P, Roche N, Initiatives BPCO ScientificCommittee Clinical COPD phenotypes: a novel approach using principal componentand cluster analyses. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:531–539. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00175109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahousse L, Seys LJM, Joos GF, Franco OH, Stricker BH, Brusselle GG. Epidemiology and impact of chronic bronchitis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1602470. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02470-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prudente R, Franco EAT, Mesquita CB, Ferrari R, de Godoy I, Tanni SE. Predictors of mortality in patients with COPD after 9 years. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;17(13):3389–3398. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S174665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Torres JP, Cote CG, López MV, Casanova C, Díaz O, Marin JM, et al. Sex differences in mortality in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:528–535. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00096108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.