Abstract

Background

Although stem cell transplantation has been successfully performed for cerebral palsy (CP) related to oxygen deprivation, clinical trials involving the use of stem cell transplantation for CP related to neonatal icterus have not been reported. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of transplantation of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell (BMMC) for improving gross motor function and muscle tone in children with CP related to neonatal icterus.

Methods

This open-label, uncontrolled clinical trial, which included 25 patients with CP related to neonatal icterus who had a Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) score between level II and level V, was conducted between July 2014 and July 2017 at Vinmec International Hospital (Vietnam). BMMC were harvested from the patients’ iliac crests. Two procedures involving BMMC transplantation via the intrathecal route were performed: the first transplantation was performed at baseline, and the second transplantation was performed 6 months after the first transplantation. Gross motor function and muscle tone were measured at three time points (baseline, 6 months, and 12 months) using the Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM) and the Modified Ashworth Scale.

Results

In this trial, we observed significant improvement in gross motor function and a significant decrease in muscle tone values. Total score on the 88-item GMFM (GMFM-88), scores on each GMFM-88 domain, and the 66-item GMFM (GMFM-66) percentile were significantly enhanced at 6 months and 12 months after the first transplantation compared with the corresponding baseline measurements (p-values < 0.05). In addition, a significant reduction was observed in muscle tone score after the transplantations (p-value < 0.05).

Conclusion

Autologous BMMC transplantation can improve gross motor function and muscle tone in children with CP related to neonatal icterus.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03123562. Retrospectively registered on December 26, 2017.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12887-019-1669-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Stem cells, Neonatal icterus, Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation

Background

Neonatal icterus is a physiological condition that affects 60–70% of newborns worldwide [1]. It is estimated that 50% of term infants and 80% of preterm infants develop icterus, which typically manifests 2–4 days after birth. In general, neonatal icterus responds well to phototherapy, albumin infusion, or blood exchange [2, 3]. However, neonates with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can develop acute encephalopathy with focal necrosis of neurons and glia. Loss of axon neurites and myelin fibres and increased blood vessel density with poorly defined lumen structures have been observed in autopsied brain tissue from premature infants with kernicterus [4–12]. Acute bilirubin encephalopathy affects long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Bilirubin-induced damage to the brain can result in CP, deafness, and/or hearing loss [5–13]. In previous research, the risk for CP in neonates with hyperbilirubinemia was found to be 0.57 per 100,000 births [14].

The traditional treatment for CP is physiotherapy, which exhibits limited efficacy. The benefits of stem cell transplantation as a treatment for CP have recently been reported [15–36]. However, no clinical trials involving the use of stem cell transplantation for CP related to neonatal icterus have been reported. Since 2014, autologous BMMC transplantation for patients with CP related to neonatal icterus has been performed at Vinmec International Hospital. The aim of this study was to assess improvement in gross motor function and muscle tone in children with CP related to neonatal icterus after BMMC transplantation.

Methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria

Sex: either sex.

Age: from 2 to 15 years.

Gross Motor Function Classification System [37] score: between level II and level V.

Previous history of icterus during the neonatal period.

Exclusion criteria

Coagulation disorder.

Severe health condition such as cancer; failure of the heart, lungs, liver, or kidneys; or an active infection.

Study design

An open-label, uncontrolled clinical trial.

Research setting and duration

The study carried out at Vinmec Times City International Hospital from July 2014 to July 2017.

Sample size

A study (2013) revealed that the mean of GMFM-66 score was 42.6 ± 15.59 [27]. We expected that it increases by 20.5% after 12 months intervention.

Alpha = 0.05, Power = 80%, N = 25.

During the study period, 33 patients with CP related to neonatal icterus were screened, 25 patients met the inclusion criterial.

Clinical assessment

A comprehensive clinical examination with a particular focus on gross motor function and muscle tone was performed by an experienced physiotherapist at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after treatment. Gross motor function was classified into 5 different levels according to Gross Motor Function Classification System.

Changes in gross motor function were evaluated using the 88-item Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM-88) [38], which consists of 88 items categorized into five domains: A. Lying and Rolling; B. Sitting; C. Crawling and Kneeling; D. Standing; E. Walking, Running and Jumping. The Gross Motor Ability Estimator (GMAE) was used to enter individual item scores, calculate GMFM-88 scores and convert these scores to 66-item Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM-66) scores [39]. GMFM-66 percentile was used to illustrate the relative motor function of each participant compared to children of the same age with the same GMFCS level, excluding interference induced by improvement with age.

Muscle tone was assessed using the Modified Ashworth Scale [40].

The GMFM-88 and GMFM-66 percentiles were primary outcomes, and the Modified Ashworth Scale score was the secondary outcome.

Laboratory and imaging diagnostics

All participants were tested for HIV, Hepatitis B virus, and Hepatitis C virus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography of the brain were also performed to assess the extent of brain injury.

Isolation of BMMCs

Bone marrow aspiration was conducted under general anesthesia in an operating theater at Vinmec International Hospital. The required bone marrow volume was calculated in accordance with each participant’s body weight. Based on our prior experience, this volume was determined as follows: 8 mL/kg for patients who weighed less than 10 kg and [80 mL + (body weight in kg - 10) × 7 mL] for patients who weighed more than 10 kg, with a total volume of no more than 200 mL [16]. BMMC separation was performed using density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll [41]. The number of hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+ cells) and the viability of BMMC were evaluated using flow cytometry.

Transplantation of BMMCs

Each patient underwent two BMMC transplantations, the first of which was performed immediately after harvested bone marrow was processed. The remaining BMMC were stored in liquid nitrogen at − 196 °C. The second transplantation was performed 6 months after the first transplantation. The average numbers of mononuclear cells and CD34+ cells per kg body weight were 17.4 ± 11.9 × 106 and 1.5 ± 1.4 × 106, respectively, for the first transplantation and 15.0 ± 12.8 × 106 and 1.1 ± 1.1 × 106, respectively, for the second transplantation. The average cell viabilities before the first and second transplantations were 96.9 and 71%, respectively. Each dose of cells was mixed with physiological saline to a volume of 10 mL for administration. Cells were then intrathecally infused into the space between the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae using an 18-gauge needle. This procedure was conducted in the recovery room by an experienced anesthesiologist and lasted 30 min.

Rehabilitative therapy

After stem cell transplantation, all children received extensive rehabilitative therapy by rehabilitative physicians and physiotherapists for 12 days (1 h per day) at the rehabilitative center of Vinmec Times City International Hospital. Parents were instructed on how to perform continuous rehabilitative at home.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are used to illustrate the demographics of children with CP related to neonatal icterus. Gross motor function and muscle tone at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months were compared using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

A t-test was used to assess changes in the mean GMFM-88 score, GMFM-66 percentile, and Modified Ashworth Scale score at 12 months after stem cell transplantation by gender.

Changes in these mean scores by age group (< 36 months, 36–72 months, > 72 months) and GMFCS level were evaluated at 12 months after stem cell transplantation by one-way ANOVA. Bonferroni test in Post Hoc was used to determine the difference in the mean of each age group or the GMFCS level.

A p-value less than 0.05 was considered the threshold for significance. Data analyses were performed using STATA software version 12.0.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Twenty-five patients with CP related to neonatal icterus, including 15 males and 10 females, were enrolled in this study. The median age for all study subjects was 5.4 years (range: 2–15 years). All patients suffered from bilateral spastic CP. The severities of patients’ conditions based on GMFCS level are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient severity according to GMFCS classification

| GMFCS level | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| II | 2 | 8.0 |

| III | 3 | 12.0 |

| IV | 6 | 24.0 |

| V | 14 | 56.0 |

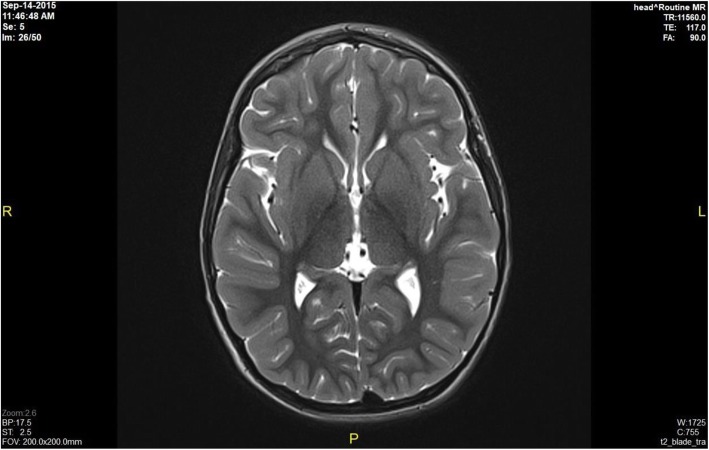

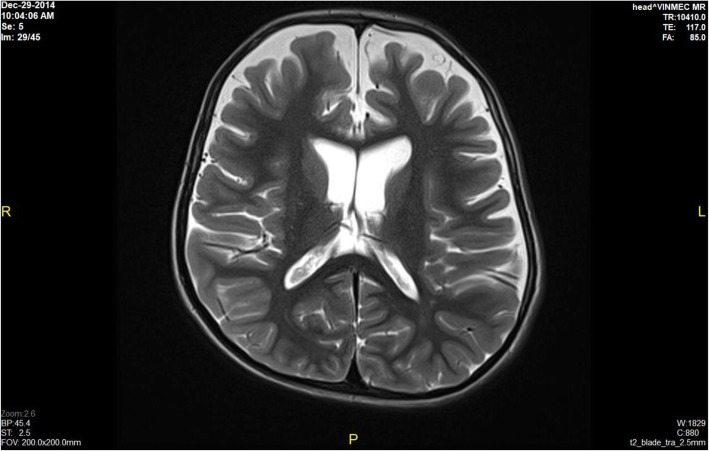

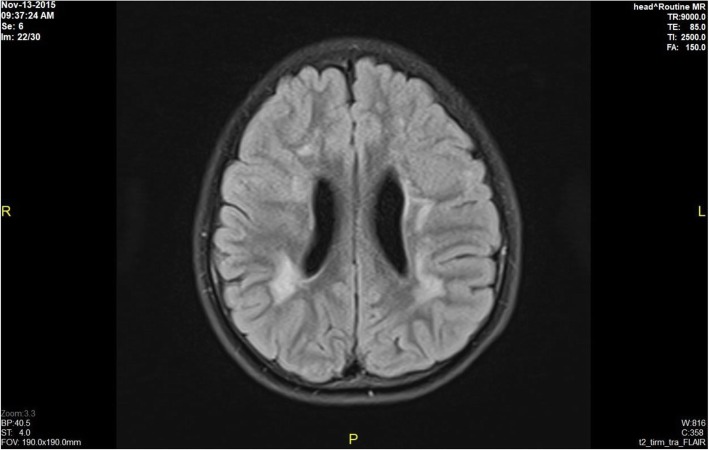

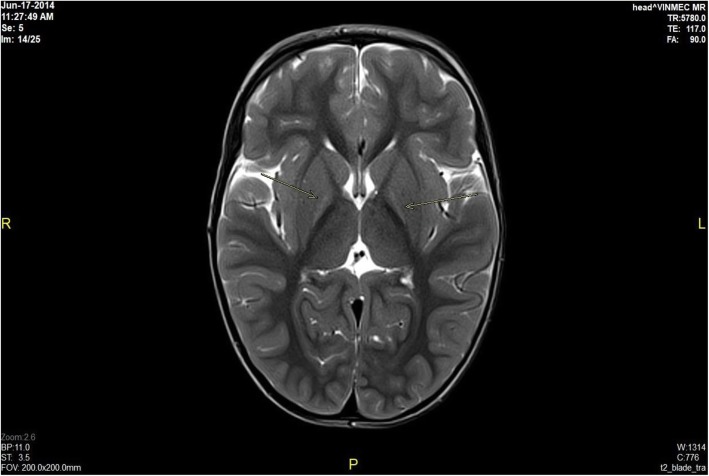

Brain MRI results revealed bilateral globus pallidus lesions, mild cerebral atrophy in the supratentorial area, periventricular white matter lesions, and no abnormalities in 60, 8, 8, and 24% of the patients, respectively. Information related to MRI scans showing brain damage is described detail in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Fig. 1 - Normal brain, Fig. 2 - Mild cerebral atrophy in the supratentorial region, Fig. 3 - Periventricular white matter lesions, Fig. 4 - Bilateral globus pallidus lesions).

Fig. 1.

Normal brain

Fig. 2.

Mild cerebral atrophy in the supratentorial region

Fig. 3.

Periventricular white matter lesions

Fig. 4.

Bilateral globus pallidus lesions

Gross motor function and muscle tone at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after stem cell transplantation

Overall, gross motor function was markedly improved at 6 and 12 months after stem cell transplantation, with median scores of 35.8 (27.6) and 53.2 (28.2), respectively, versus 18.3 (17.6) at baseline. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test indicated that the GMFM-66, GMFM-88 and sub-domain median scores were significantly higher after transplantation than at baseline (p-value < 0.05).

The GMFM-66 percentile was significantly enhanced at 6 and 12 months after stem cell transplantation, with median scores of 22.5 (22.6) and 40.1 (5.5), respectively, compared to the median baseline score of 19.3 (19.6) (p-value < 0.05).

Muscle tone decreased significantly from a median Modified Ashworth Scale score of 4.0 (0.25) at baseline to 3.3 (0.63) at 6 months after stem cell transplantation and 3.0 (0.25) at 12 months after stem cell transplantation (p-values < 0.05). This observed improvement in gross motor functions and muscle tone is presented in greater detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gross motor function improvement after stem cell transplantation

| Baseline Median (IQR) |

6 months post-transplantation Median (IQR) |

p-value at 6 months | 12 months post-transplantation Median (IQR) |

p-value at 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total GMFM-88 score | 18.3 (17.6) | 35.8 (27.6) | 0.0003 | 53.2 (28.2) | 0.0000 |

| Lying and rolling | 34.0 (26.0) | 48.0 (10.0) | 0.0011 | 51.0 (2.0) | 0.0000 |

| Sitting | 15.0 (24.0) | 38.0 (31.0) | 0.0003 | 56.0 (9.0) | 0.0000 |

| Crawling and kneeling | 0.0 (5.0) | 9.0 (28.0) | 0.0001 | 29.0 (27.0) | 0.0000 |

| Standing | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (4.0) | 0.0084 | 3.0 (14.0) | 0.0003 |

| Walking, running and jumping | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0256 | 0.0 (5.0) | 0.0084 |

| GMFM-66 score | 26.7 (14.8) | 38.4 (12.9) | 0.0003 | 45.6 (10.7) | 0.0000 |

| GMFM-66 percentile | 19.3 (19.6) | 22.5 (22.6) | 0.0002 | 40.1 (5.5) | 0.0000 |

| Ashworth score | 4.0 (0.25) | 3.3 (0.63) | 0.0000 | 3.0 (0.25) | 0.0000 |

IQR Interquartile range

*Significant at p ≤ 0.05

Relationships between patient characteristics and changes in gross motor function and muscle tone

The result showed no relationship between improvement in gross motor function and muscle tone based on patient age, sex, or GMFCS level (p-value > 0.05) (see details in Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in gross motor function and muscle tone after stem cell transplantation according to patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Change in GMFM-88 score Mean [95% CI] |

Change in GMFM-66 percentile Mean [95% CI] |

Change in Ashworth score Mean [95% CI] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | ||||||

| Male | 32.4 [25.2; 39.5] | p-value = 0.808 | 20.2 [16.7; 23.6] | p-value = 0.593 | 1.0 [0.7; 1.2] | p-value = 0.301 |

| Female | 31.1 [26.8;36.9] | 18.7 [13.5; 23.9] | 0.8 [0.3; 1.2] | |||

| Ageb | ||||||

| < 36 months | 37.1 [31.9; 42.3] | p-value = 0.368 | 21.7 [16.2; 27.1] | p-value = 0.776 | 0 | p-value = 0.393 |

| 36–72 months | 30.9 [22.4; 39.5] | 17.9 [13.7; 22.1] | 0.8 [0.6; 1.0] | |||

| > 72 months | 31.9 [25.1; 38.7] | 21.0 [17.1; 25.0] | 0.9 [0.5; 1.4] | |||

| GMFCSb | ||||||

| Level II | 8.9 [6.0; 11.8] | p-value = 0.574 | 9.6 [1.1; 18.1] | p-value = 0.929 | 0.8 [0.7; 0.9] | p-value = 0.316 |

| Level III | 21.1 [12.6; 29.5] | 13.9 [6.9; 20.8] | 0.6 [0.04; 1.2] | |||

| Level IV | 39.5 [31.8; 47.2] | 18.6 [15.0; 22.2] | 1.0 [0.9; 1.0] | |||

| Level V | 34.2 [28.9; 39.4] | 22.6 [19.5; 25.7] | 0.9 [0.6; 1.3] | |||

at-test

bone-way ANOVA test (Bonferroni test for Post Hoc analysis)

Adverse events

No severe complications occurred during the study period. Minor complications occurred and were managed with standard medications. Adverse events included vomiting (32%), local pain (16%), and mild fever without any identified infection (4%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this report describes the first clinical trial to assess the impact of autologous BMMC transplantation on motor function and muscle tone in children with CP related to neonatal icterus.

Overall, observations from this clinical trial indicate that gross motor function was significantly improved at 6 and 12 months after stem cell transplantation. The GMFM-88 score increased by 17.5 and 34.9 at 6 months, and 12 months after transplantation than that at baseline, respectively. This level of improvement was higher than the study of Wang [27] but lower than our previous study [16]. The GMFM-88 score in Wang’s study increased by 7.89 at 6 months after transplantation than baseline scores. The GMFM-88 in our study in using stem cell transplantation for CP related to oxygen deprivation increased by 25.1 at 6 months after the transplantation.

In 2016, Kulak conducted a systematic review 7 studies on stem cell treatment for cerebral palsy with fives studies using the GMFM-88 score as a primary outcome. The improvement in the GMFM-88 scale was noted in all five studies after transplantation. However, the causes of cerebral palsy were not identified in those study [42].

In accordance to previous studies using stem cell transplantation for children with CP, we observed a significant reduction in the median Ashworth score in patients at 6 and 12 months after transplantation [16, 20, 22], indicating the effectiveness of the therapy on muscle spastic reduction in the patients.

Our results indicated that autologous intrathecal BMMC transplantation was safe for children with CP related to neonatal icterus. No complications occurred during bone marrow harvesting or BMMC infusion. During hospitalization after stem cell transplantation, only 4.2% of the patients exhibited mild fever with no signs of infection, and 34% of the patients experienced intermittent vomiting. All adverse events were easily managed with medical treatment. These findings were similar to those obtained in previous clinical trials in which autologous BMMC transplantation was used to treat for children with CP [16, 20, 22].

Adverse events were less severe in our series than in previously reported trials that involved the use of allogenic stem cells from umbilical cord blood. In such studies, severe adverse events such as pneumonia, influenza, urinary tract infection and even death were observed [32]. One explanation for this difference could be suppression of the immune system due to the use of immunosuppressive medications in allogenic umbilical cord blood transplantations. In our patients, stem cells were administered via the intrathecal route, as described in our previous report [16]. The outcomes again confirmed that this route is minimally invasive, safe and effective.

This study has some limitations. There was no control group. In addition, the follow-up time of 6 months after the 2nd stem cell transplantation was relatively short.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, we can conclude that gross motor function and muscle tone in children with CP related to neonatal icterus were remarkably improved at 6 months and 12 months after BMMC transplantation. However, these finding should be confirmed in larger, multicenter, placebo-controlled trials.

Additional file

Stem cell transplantation for children with cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus. This is a dataset file of study on autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus. The data includes demographic data, gross motor function of patients with cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus such as GMFM-88 total score, GMFM-66 percentile. The dataset consists of 25 observations and 93 variables. (XLSX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge American journal experts for editing English for our manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BMMC

Bone marrow mononuclear cell

- CP

Cerebral palsy

- GMAE

Gross Motor Ability Estimator

- GMFCS

Gross Motor Function Classification System

- GMFM

Gross Motor Function Measure

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

Authors’ contributions

LNT, KNT, CVD, DNV, ABV: participated in the study concept, design and data collection. KNT, PNH: did data analysis. LNT, KNT, CVD, ABV, ANTP, MND participated in acquisition and interpretation of the data, drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

We did not receive any funding to conduct this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional file 1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vinmec International Hospital on March 10, 2014. The reference number for the ethics committee is 381/2015/QD-VINMEC. The committee evaluated the ethical aspects of the study in accordance with The World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. The study was explained in detail to parents of the participants. Parental written informed consent was obtained well before patient enrollment in all cases.

Consent for publication

Parental written informed consent was obtained well before patient enrollment in all cases. This consent included their agreement to the publication of indirect identifiers for patients, such as age and gender.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liem Nguyen Thanh, Email: v.liemnt@vinmec.com.

Kien Nguyen Trung, Email: v.kiennt25@vinmec.com.

Chinh Vu Duy, Email: v.chinhvd@vinmec.com.

Doan Ngo Van, Email: v.doannv1@vinmec.com.

Phuong Nguyen Hoang, Email: v.phuongnh9@vinmec.com.

Anh Nguyen Thi Phuong, Email: v.anhntp@vinmec.com.

Minh Duy Ngo, Email: v.minhnd@vinmec.com.

Thinh Nguyen Thi, Email: v.thinhnt@vinmec.com.

Anh Bui Viet, Email: v.anhbv@vinmec.com.

References

- 1.David K, Phyllis A, Susan R. Understanding newborn jaundice. J Perinatol. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S21–S24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le LT, Partridge JC, Tran BH, Le VT, Duong TK, Nguyen HT, et al. Care practices and traditional beliefs related to neonatal jaundice in northern Vietnam: a population-based, cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:264. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali R, Ahmed S, Qadir M, Ahmad K. Icterus Neonatorum in near-term and term infants: an overview. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(2):153–160. doi: 10.12816/0003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson L, Bhutani VK, Karp K, Sivieri EM, Shapiro SM. Clinical report from the pilot USA kernicterus registry (1992 to 2004) J Perinatol: official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2009;29(Suppl 1):S25–S45. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukhopadhyay K, Chowdhary G, Singh P, Kumar P, Narang A. Neurodevelopmental outcome of acute bilirubin encephalopathy. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56(5):333–336. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okumura A, Kidokoro H, Shoji H, Nakazawa T, Mimaki M, Fujii K, et al. Kernicterus in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e1052–e1058. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasul CH, Hasan MA, Yasmin F. Outcome of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh. Malays J Med Sci. 2010;17(2):40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maimburg RD, Bech BH, Bjerre JV, Olsen J, Moller-Madsen B. Obstetric outcome in Danish children with a validated diagnosis of kernicterus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(9):1011–1016. doi: 10.1080/00016340903124917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro SM. Chronic bilirubin encephalopathy: diagnosis and outcome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15(3):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan M, Bromiker R, Hammerman C. Severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and kernicterus: are these still problems in the third millennium? Neonatology. 2011;100(4):354–362. doi: 10.1159/000330055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farouk ZL, Muhammed A, Gambo S, Mukhtar-Yola M, Umar Abdullahi S, Slusher TM. Follow-up of Children with Kernicterus in Kano, Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 2017;64(3):176–182. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmx041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wusthoff CJ, Loe IM. Impact of bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction on neurodevelopmental outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20(1):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro SM. Bilirubin toxicity in the developing nervous system. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29(5):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YW, Kuzniewicz MW, Wickremasinghe AC, Walsh EM, Wi S, McCulloch CE, et al. Risk for cerebral palsy in infants with total serum bilirubin levels at or above the exchange transfusion threshold: a population-based study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):239–246. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantake M, Hirano A, Sano M, Urushihata N, Tanemura H, Oki K, et al. Transplantation of allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a cerebral palsy patient (retracted) Regen Med. 2017;12(5):575. doi: 10.2217/rme-2017-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen LT, Nguyen AT, Vu CD, Ngo DV, Bui AV. Outcomes of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for cerebral palsy: an open label uncontrolled clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0859-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park KI, Lee YH, Rah WJ, Jo SH, Park SB, Han SH, et al. Effect of intravenous infusion of G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells on upper extremity function in cerebral palsy children. Ann Rehabil Med. 2017;41(1):113–120. doi: 10.5535/arm.2017.41.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Fu X, Dai G, Wang X, Zhang Z, Cheng H, et al. Comparative analysis of curative effect of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell and bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation for spastic cerebral palsy. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abi Chahine NH, Wehbe TW, Hilal RA, Zoghbi VV, Melki AE, Habib EB. Treatment of cerebral palsy with stem cells: a report of 17 cases. Int J of Stem Cells. 2016;9(1):90–95. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2016.9.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bansal H, Singh L, Verma P, Agrawal A, Leon J, Sundell IB, et al. Administration of Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells for treatment of cerebral palsy patients: a proof of concept. J Stem Cells. 2016;11(1):37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng M, Lu A, Gao H, Qian C, Zhang J, Lin T, et al. Safety of allogeneic umbilical cord blood stem cells therapy in patients with severe cerebral palsy: a retrospective study. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:325652. doi: 10.1155/2015/325652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, Sane H, Gokulchandran N, Kulkarni P, Gandhi S, Sundaram J, et al. A clinical study of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for cerebral palsy patients: a new frontier. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:905874. doi: 10.1155/2015/905874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zali A, Arab L, Ashrafi F, Mardpour S, Niknejhadi M, Hedayati-Asl AA, et al. Intrathecal injection of CD133-positive enriched bone marrow progenitor cells in children with cerebral palsy: feasibility and safety. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(2):232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Hu H, Hua R, Yang J, Zheng P, Niu X, et al. Effect of umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells on motor functions of identical twins with cerebral palsy: pilot study on the correlation of efficacy and hereditary factors. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Huang L, Gu J, Zhou X. Therapy for Cerebral Palsy by Human Umbilical Cord Blood Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation Combined With Basic Rehabilitation Treatment: A Case Report. Glob Pediatr Health. 2015;2:2333794X15574091. doi: 10.1177/2333794X15574091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shroff G, Gupta A, Barthakur JK. Therapeutic potential of human embryonic stem cell transplantation in patients with cerebral palsy. J Transl Med. 2014;12:318. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Cheng H, Hua R, Yang J, Dai G, Zhang Z, et al. Effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells on gross motor function measure scores of children with cerebral palsy: a preliminary clinical study. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(12):1549–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren C, Geng RL, Ge W, Liu XY, Chen H, Wan MR, et al. An observational study of autologous bone marrow-derived stem cells transplantation in seven patients with nervous system diseases: a 2-year follow-up. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;69(1):179–187. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon JH, Kim MJ, Song SY, Lee YJ, Choi YY, Kim SH, et al. Safety and efficacy of G-CSF mobilization and collection of autologous peripheral blood stem cells in children with cerebral palsy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013;49(3):516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen A, Hamelmann E. First autologous cell therapy of cerebral palsy caused by hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in a child after cardiac arrest-individual treatment with cord blood. Case Rep Transplant. 2013;2013:951827. doi: 10.1155/2013/951827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Ji H, Zhou J, Xie J, Zhong Z, Li M, et al. Therapeutic potential of umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells transplantation for cerebral palsy: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2013;2013:146347. doi: 10.1155/2013/146347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min K, Song J, Kang JY, Ko J, Ryu JS, Kang MS, et al. Umbilical cord blood therapy potentiated with erythropoietin for children with cerebral palsy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Stem Cells. 2013;31(3):581–591. doi: 10.1002/stem.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purandare C, Shitole DG, Belle V, Kedari A, Bora N, Joshi M. Therapeutic potential of autologous stem cell transplantation for cerebral palsy. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:825289. doi: 10.1155/2012/825289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He S, Luan Z, Qu S, Qiu X, Xin D, Jia W, et al. Ultrasound guided neural stem cell transplantation through the lateral ventricle for treatment of cerebral palsy in children. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7(32):2529–2535. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.32.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Li M, Yu A, Zhang F, Dai G, Cheng H, Wang X, et al. Treatment of one case of cerebral palsy combined with posterior visual pathway injury using autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Transl Med. 2012;10:100. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma A, Gokulchandran N, Chopra G, Kulkarni P, Lohia M, Badhe P, et al. Administration of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in children with incurable neurological disorders and injury is safe and improves their quality of life. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(Suppl 1):S79–S90. doi: 10.3727/096368912X633798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(4):214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dianne R, Peter R. Gross motor function measure score sheet [https://canchild.ca/system/tenon/assets/attachments/000/000/218/original/gmfm-88_and_66_scoresheet.pdf]. Accessed 15 May 2016.

- 39.Foundation Cs. Gross Motor Ability Estimator (GMAE-2) Scoring Software for the GMFM [https://canchild.ca/en/resources/191-gross-motor-ability-estimator-gmae-2-scoring-software-for-the-gmfm]. Accessed 25 June 2016.

- 40.Richard B, Melissa S. Modified Ashworth Scale Instructions [http://www.rehabmeasures.org/PDF%20Library/Modified%20Ashworth%20Scale%20Instructions.pdf]. Accessed 5 May 2016.

- 41.Sally AQ. Isolation of Human Blood Mononuclear Cells using Ficoll-Hypaque Density Gradient Centrifugation [https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/medialibraries/urmcmedia/rochester-human-immunology-center/documents/HIC-1-0020Approved.pdf]. Accessed May 2017.

- 42.Kulak-Bejda A, Kulak P, Bejda G, Krajewska-Kulak E, Kulak W. Stem cells therapy in cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Brain and Development. 2016;38(8):699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Stem cell transplantation for children with cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus. This is a dataset file of study on autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus. The data includes demographic data, gross motor function of patients with cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus such as GMFM-88 total score, GMFM-66 percentile. The dataset consists of 25 observations and 93 variables. (XLSX 20 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional file 1.