Key Points

Question

What is the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy for minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack?

Findings

In this pooled analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials, early and short-term clopidogrel-aspirin treatment was associated with a reduction in the risk of major ischemic events without increasing the risk of major hemorrhage in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. The main net clinical benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy occurred within the first 21 days.

Meaning

This analysis suggests that, in patients with acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack, dual antiplatelet therapy should be initiated as soon as possible, but preferably within 24 hours after symptom onset, and continued for a duration of 21 days.

This pooled analysis combines data from 2 randomized clinical trials to estimate the efficacy and risk of dual antiplatelet therapy after minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Abstract

Importance

Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin is effective for secondary prevention after minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Uncertainties remained about the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy for minor stroke or TIA.

Objective

To obtain precise estimates of efficacy and risk of dual antiplatelet therapy after minor ischemic stroke or TIA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This analysis pooled individual patient–level data from 2 large-scale randomized clinical trials that evaluated clopidogrel-aspirin as a treatment to prevent stroke after a minor stroke or high-risk TIA. The Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial enrolled patients at 114 sites in China from October 1, 2009, to July 30, 2012. The Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial enrolled patients at 269 international sites from May 28, 2010, to December 19, 2017. Both were followed up for 90 days. Data analysis occurred from November 2018 to May 2019.

Interventions

In the 2 trials, patients with minor stroke or high-risk TIA were randomized to clopidogrel-aspirin or aspirin alone within 12 hours (POINT) or 24 hours (CHANCE) of symptom onset.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary efficacy outcome was a major ischemic event (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes). The primary safety outcome was major hemorrhage.

Results

The study enrolled 5170 patients (CHANCE) and 4881 patients (POINT). Analysis included individual data from 10 051 patients (5016 in the clopidogrel-aspirin treatment group and 5035 in the control group) with a median age of 63.2 (interquartile range, 55.0-72.9) years; 6106 patients (60.8%) were male. Clopidogrel-aspirin treatment reduced the risk of major ischemic events at 90 days compared with aspirin alone (328 of 5016 [6.5%] vs 458 of 5035 [9.1%]; hazard ratio [HR], 0.70 [95% CI, 0.61-0.81]; P < .001), mainly within the first 21 days (263 of 5016 [5.2%] vs 391 of 5035 [7.8%]; HR, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.56-0.77]; P < .001), but not from day 22 to day 90. No evidence of heterogeneity of treatment outcome across trials or prespecified subgroups was observed. Major hemorrhages were more frequent in the clopidogrel-aspirin group, but the difference was nonsignificant.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this analysis of the POINT and CHANCE trials, the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy appeared to be confined to the first 21 days after minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy with the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin was shown to reduce the early risk of new stroke in patients with minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in a Chinese population enrolled in the Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial.1 The efficacy of dual antiplatelet therapy was further validated in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand in the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial.2 However, an increase in major hemorrhage observed in the POINT trial led to concerns about bleeding risks in dual antiplatelet therapy.3 Uncertainties remained about the risks and benefits of dual antiplatelet therapy and the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy for minor stroke or TIA. Moreover, the 2 trials were each moderate in size, whereas pooled-data analysis can provide more precise estimates of treatment outcomes. As the investigators from the CHANCE and POINT trials, we sought to address these questions about the risks and benefits of dual antiplatelet therapy after minor ischemic stroke or TIA by analyzing pooled individual patient–level data from the 2 trials.

Methods

Study Inclusion and Participants

All individual patient–level data from the CHANCE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00979589) and the POINT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00991029) were extracted and pooled. Details on the design and major results of the 2 trials have been published elsewhere.1,2 Characteristics of the 2 trials are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement. In brief, both trials were double-blind randomized clinical trials to assess the efficacy and safety of combined treatment with clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone for minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale ≤3) and high-risk TIA (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of symptoms, and presence of diabetes [ABCD2] score ≥4). The CHANCE trial used 21 days of dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel alone from 22 to 90 days in the clopidogrel-aspirin arm, whereas the POINT trial used 90 days of dual antiplatelet therapy in the clopidogrel-aspirin arm. The 2 trials were approved by the ethics committee at each participating site. Each participant or his or her representative provided written informed consent before being enrolled in each trial.

We established a collaborative group to pool individual patient–level data from the 2 trials using data extracted directly from study databases. The study statisticians (Y.P. and J.J.E.) from each trial extracted, collated, and cross checked all data against previous publications.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome in this pooled analysis was a new major ischemic event (eg, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes) at 90 days. The secondary efficacy end points were each component of the primary efficacy outcome, a composite of primary efficacy outcome and major hemorrhage and stroke (whether ischemic or hemorrhagic).

The primary safety outcome was the presence of major hemorrhage at 90 days. The secondary safety outcomes were hemorrhagic stroke, minor hemorrhage, major or minor hemorrhage, and death from any cause.

Major hemorrhage was defined differently in the 2 trials. We did not attempt to reconcile these differences in the pooled analysis because each definition was used in the adjudication process for each trial and because the differences were not substantial. Major hemorrhage in the POINT trial was defined as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, intraocular bleeding causing visual acuity loss, transfusion of 2 or more units of red blood cells or an equivalent amount of whole blood, hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization, or death attributable to hemorrhage.2 Major hemorrhage in the CHANCE trial was defined as moderate to severe bleeding according to the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) definition.1,4 Minor hemorrhage in the POINT trial was defined as all hemorrhagic events leading to an interruption or discontinuation of therapy but not classifiable as major hemorrhagic events, including asymptomatic intracranial hemorrhage and bleeding events associated with surgical procedures but not those associated with accidental trauma.2 Minor hemorrhage in the CHANCE trial was defined as any bleeding that was not classifiable as moderate to severe bleeding by the GUSTO definition.1

Statistical Analysis

All analyses adhered to the intention-to-treat principle based on the randomized treatment assignment. Because the 2 trials were conducted independently in different study sites with different populations, geographic locations, and health systems, we specified fixed effects for trial and treatment assignment and random effects rather than fixed effects for study site to avoid the assumption of a common effect size between the 2 trials. For efficacy and safety outcomes, interaction of trial with treatment assignment was specified as a fixed effect in mixed-effects Cox regression models to account for between-trial differences in treatment outcomes. If the interaction term was not significant, we then used mixed-effects Cox regression models with fixed effects for trial and treatment assignment and random effects for study site to estimate the treatment outcomes.

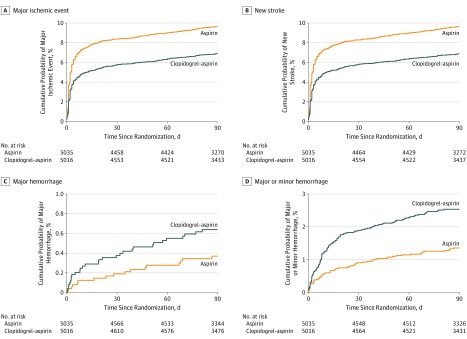

We developed 3 models. In the first model, we adjusted only for the trial. In the second model, we further adjusted for sex, age, race, history of congestive heart failure, known atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or previous smoking status, qualifying event type (ischemic stroke or TIA), and time to randomization. In the third model, lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatments were further adjusted. The third model was only treated as a sensitivity analysis because of missing data on lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatments. We calculated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% CIs, using mixed-effects Cox regression models. For the outcomes of a major ischemic event, new stroke, major hemorrhage, and major or minor hemorrhage, we presented the time to the first event using Kaplan-Meier curves (1 − proportion free of event).

We further tested for heterogeneity of treatment outcome by prespecified, clinically relevant variables using mixed-effects models with interaction terms of treatment by prespecified variable. Prespecified variables included age, sex, race, previous ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or previous smoking status, qualifying event, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, ABCD2 score, and time to randomization. All models were adjusted for the same covariates as the second model used for the primary analyses.

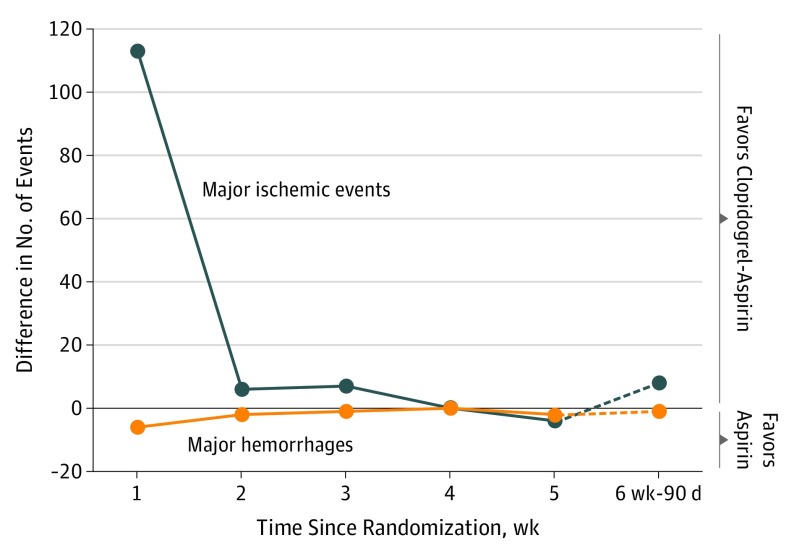

To determine the short-term course of relative risks and benefits of clopidogrel and aspirin, we presented differences in the number of events between the clopidogrel-aspirin group and the aspirin-alone group, stratified by time since randomization for each week for the first 5 weeks and the sixth week (from day 36) to day 90. To account for the different duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in the 2 trials (in that CHANCE used 21 days of dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel alone from 22 to 90 days in the clopidogrel-aspirin arm, whereas POINT used 90 days of dual antiplatelet therapy in the clopidogrel-aspirin arm), separate analyses for the primary efficacy and safety outcomes were performed for 0 to 21 days and 22 to 90 days. We then calculated adjusted HRs with their 95% CIs using mixed-effects Cox regression models for each period. Separate analyses were also performed for 0 to 10 days and 11 to 21 days to explore the efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy from 11 to 21 days.5 For the period between 22 and 90 days, separate analyses were performed for each trial, respectively.

We also calculated the net clinical benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy for the total time frame of the trials and 0 to 21 days and 22 to 90 days. The number of major hemorrhage events attributable to dual antiplatelet therapy was subtracted from the number of major ischemic events prevented by dual antiplatelet therapy with weights of 0.5 to 1.2: net benefit = (major ischemic event in the aspirin group − major ischemic event in the clopidogrel-aspirin group) − major hemorrhage weight × (major hemorrhage in the clopidogrel-aspirin group − major hemorrhage in the aspirin group). The weight accounts for the outcomes associated with a major hemorrhage, compared with a major ischemic event.6 In sensitivity analysis, we also added minor hemorrhage with a weight of 0.1 to 0.5, accounting for the outcomes of a minor hemorrhage compared with a major ischemic event: net benefit = (major ischemic event in the aspirin group − major ischemic event in the clopidogrel-aspirin group) − major hemorrhage weight × (major hemorrhage in the clopidogrel-aspirin group − major hemorrhage in the aspirin group) − minor hemorrhage weight × (minor hemorrhage in the clopidogrel-aspirin group − minor hemorrhage in the aspirin group).

Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data analysis occurred from November 2018 to May 2019.

Results

Study Participants and Characteristics

By pooling data from the 2 trials, we obtained data for 10 051 participants, of whom 5016 patients were assigned to receive clopidogrel-aspirin and 5035 patients were assigned to receive aspirin alone. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the clopidogrel-aspirin group and the aspirin-alone group (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Among these patients, 6106 (60.8%) were male, and the median (interquartile range) age was 63.2 (55.0-72.9) years old; 6498 patients (64.7%) had a minor stroke as the qualifying event, and 3553 (35.3%) presented with TIA.

Efficacy and Safety Outcome

Table 1 shows the efficacy and safety outcomes of the pooled data. A major ischemic event occurred in 328 patients (6.5%) receiving clopidogrel-aspirin and 458 patients (9.1%) receiving aspirin alone at 90 days (adjusted HR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.61-0.81]; P < .001; Table 1 and Figure 1A). At 90 days, a new stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) had occurred in 328 patients (6.5%) receiving clopidogrel-aspirin and 458 patients (9.1%) receiving aspirin alone (adjusted HR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.61-0.80]; P < .001; Table 1 and Figure 1B). Further adjustment for lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatments showed similar results (HR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.60-0.82]; P < .001; Table 1; model 3). No interaction of trial by treatment was observed for the composite primary efficacy outcome (207 of 2584 [8.0%] vs 298 of 2586 [11.5%] in CHANCE; 121 of 2432 [5.0%] vs 160 of 2449 [6.5%] in POINT; P = .45 for interaction) or new stroke (212 of 2584 [8.2%] vs 303 of 2586 [11.7%] in CHANCE; 116 of 2432 [4.8%] vs 156 of 2449 [6.4%] in POINT; P = .56 for interaction). We also found no evidence of heterogeneity of treatment outcome on major ischemic events across the prespecified subgroups (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Efficacy and Safety Outcomes.

| Outcome | Patients, No. (%) | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (n = 5035) | Clopidogrel-Aspirin (n = 5016) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Efficacy Outcomes | ||||||||

| Composite of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from ischemic vascular causes | 458 (9.1) | 328 (6.5) | 0.71 (0.61-0.81) | <.001 | 0.70 (0.61-0.81) | <.001 | 0.70 (0.60-0.82) | <.001 |

| Ischemic stroke | 450 (8.9) | 316 (6.3) | 0.69 (0.60-0.80) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.59-0.79) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.59-0.81) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 9 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) | 1.44 (0.62-3.38) | .40 | 1.40 (0.60-3.29) | .44 | 2.30 (0.60-8.93) | .23 |

| Death from ischemic vascular causes | 7 (0.1) | 9 (0.2) | 1.28 (0.48-3.42) | .63 | 1.22 (0.45-3.29) | .69 | 0.83 (0.20-3.44) | .80 |

| Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke | 458 (9.1) | 328 (6.5) | 0.71 (0.61-0.81) | <.001 | 0.70 (0.61-0.80) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.59-0.81) | <.001 |

| Disabling or fatal stroked | 307 (6.1) | 232 (4.6) | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | <.001 | 0.74 (0.62-0.87) | <.001 | 0.72 (0.60-0.87) | <.001 |

| Nondisabling strokee | 152 (3.0) | 96 (1.9) | 0.63 (0.48-0.81) | <.001 | 0.62 (0.48-0.80) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.47-0.84) | .002 |

| Composite of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, death from ischemic vascular causes, and major hemorrhage | 473 (9.4) | 354 (7.1) | 0.74 (0.64-0.85) | <.001 | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | <.001 | 0.72 (0.62-0.84) | <.001 |

| Safety Outcomes | ||||||||

| Major hemorrhage | 18 (0.4) | 30 (0.6) | 1.67 (0.93-2.99) | .09 | 1.59 (0.88-2.86) | .12 | 1.20 (0.61-2.39) | .60 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 11 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) | 1.16 (0.52-2.60) | .71 | 1.06 (0.47-2.40) | .90 | 0.77 (0.30-1.95) | .58 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 46 (0.9) | 93 (1.9) | 2.02 (1.42-2.88) | <.001 | 2.01 (1.41-2.86) | <.001 | 1.87 (1.26-2.79) | .002 |

| Major or minor hemorrhage | 64 (1.3) | 123 (2.5) | 1.91 (1.41-2.58) | <.001 | 1.88 (1.39-2.54) | <.001 | 1.66 (1.18-2.35) | .004 |

| Death from any cause | 22 (0.4) | 28 (0.6) | 1.26 (0.72-2.21) | .42 | 1.17 (0.66-2.05) | .59 | 1.08 (0.54-2.16) | .82 |

Adjusted for trial, with study site as a random-effect variable in the model.

Adjusted for trial, sex, age, race, history of congestive heart failure, known atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or previous smoking status, qualifying event, and time to randomization, with study site as a random-effect variable in the model.

Adjusted for trial, sex, age, race, history of congestive heart failure, known atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or previous smoker, qualifying event, time to randomization, and lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatments, with study site as a random-effect variable in the model; only 7663 patients (76.2%) were included in the model, because antihypertensive treatment was not collected in the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke trial before 2014.

Defined by a modified Rankin Scale greater than 1.

Defined by a modified Rankin Scale of 0 or 1.

Figure 1. Cumulative Probability of Events by Treatment Assignment.

Major hemorrhage occurred in 30 patients (0.6%) receiving clopidogrel-aspirin and 18 patients (0.4%) receiving aspirin alone (adjusted HR, 1.59 [95% CI, 0.88-2.86]; P = .12; Table 1 and Figure 1C). Patients receiving clopidogrel-aspirin had a higher rate of minor hemorrhage at 90 days compared with those receiving treatment with aspirin alone (93 of 5016 [1.9%] vs 46 of 5035 [0.9%]; adjusted HR, 2.01 [95% CI, 1.41-2.86]; P < .001). No interaction of trial by treatment assignment was observed for the major hemorrhage outcome (7 of 2584 [0.3%] vs 8 of 2586 [0.3%] in CHANCE; 23 of 2432 [1.0%] vs 10 of 2449 [0.4%] in POINT; P = .13) or the minor hemorrhage outcome (53 of 2584 [2.1%] vs 33 of 2586 [1.3%] in CHANCE; 40 of 2432 [1.6%] vs 13 of 2449 [0.5%] in POINT; P = .09). Compared with aspirin, clopidogrel-aspirin was associated with a higher rate of total hemorrhage (major or minor hemorrhage: 123 of 5016 [2.5%] vs 64 of 5035 [1.3%]; adjusted HR, 1.88 [95% CI, −1.39 to 2.54]; P < .001; Table 1 and Figure 1D). Clopidogrel-aspirin treatment increased the risk of total hemorrhage in the POINT trial (adjusted HR, 2.72 [95% CI, 1.68-4.39]; P < .001) but not the CHANCE trial (adjusted HR, 1.42 [95% CI, 0.95-2.11]; P = .09; P = .04 for interaction). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in the rates of hemorrhagic stroke (13 [0.3%] vs 11 [0.2%]; P = .90) or death from any cause (28 of 5016 [0.6%] vs 22 of 5035 [0.4%]; P = .59) (Table 1).

Time-Course Analysis of Risks and Benefits

eTable 3 in the Supplement shows the time-course distribution of major ischemic events and major hemorrhages by treatment assignment. A total of 113, 6, 7, 0, −4 (excess), and 8 fewer major ischemic events occurred in the clopidogrel-aspirin group at the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth week (from day 36) to day 90, respectively (eTable 3 in the Supplement). A total of 6, 2, 1, 0, 2, and 1 excess major hemorrhages occurred in the clopidogrel-aspirin group at the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth week (from day 36) to day 90, respectively (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The absolute numbers of major ischemic events prevented by clopidogrel-aspirin exceeded the increase in major hemorrhages, particularly within the first 3 weeks of treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Difference in Number of Events by Week.

The numbers indicate difference of major ischemic events and major hemorrhage between the group receiving aspirin alone and the group receiving clopidogrel-aspirin.

Within the first 21 days after randomization, during which both trials prescribed clopidogrel-aspirin in the dual antiplatelet therapy arm, patients receiving clopidogrel-aspirin treatment had a lower rate of major ischemic events compared with those receiving aspirin alone treatment (263 of 5016 [5.2%] vs 391 of 5035 [7.8%]; adjusted HR, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.56-0.77]; P < .001; Table 2). Most major ischemic events reduction occurred within the first 10 days. From day 11 to day 21, the clopidogrel-aspirin group had a numerically lower rate of major ischemic events compared with the aspirin-alone group (25 of 4622 [0.5%] vs 34 of 4524 [0.8%]; adjusted HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.43-1.22]; P = .22; Table 2). From day 22 to day 90, during which CHANCE prescribed clopidogrel alone and POINT prescribed clopidogrel-aspirin in the dual antiplatelet therapy arm, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups in the rates of major ischemic event (65 of 4571 [1.4%] vs 67 of 4470 [1.5%]; adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI 0.67-1.32; P = .72; Table 2). Separate analyses of day 22 to day 90 showed that clopidogrel-aspirin therapy was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in major ischemic events in CHANCE (33 of 2384 [1.4%] vs 44 of 2321 [1.9%]; P = .16) and a nonsignificant increase in major ischemic events in POINT (32 of 2187 [1.5%] vs 23 of 2158 [1.1%]; P = .26; P = .07 for interaction; Table 2).

Table 2. Outcomes Associated With Clopidogrel-Aspirin vs Aspirin Alone by Time Since Randomization.

| Period | Major Ischemic Eventa | Major Hemorrhage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin, No. of Events/Total No. of Patients (%) | Clopidogrel-Aspirin, No. of Events/Total No. of Patients (%) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value | Aspirin, No. of Events/Total No. of Patients (%) | Clopidogrel-Aspirin, No. of Events/Total No. of Patients (%) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| 0-21 d | 391/5035 (7.8) | 263/5016 (5.2) | 0.66 (0.56-0.77) | <.001 | 7/5035 (0.1) | 16/5016 (0.3) | 2.11 (0.86-5.17) | .10 |

| 0-10 d | 357/5035 (7.1) | 238/5016 (4.7) | 0.65 (0.55-0.77) | <.001 | 6/5035 (0.1) | 13/5016 (0.3) | 1.97 (0.74-5.26) | .18 |

| 11-21 d | 34/4524 (0.8) | 25/4622 (0.5) | 0.72 (0.43-1.22) | .22 | 1/4624 (0.02) | 3/4682 (0.06) | 2.77 (0.28-27.02) | .38 |

| 22-90 d | 67/4470 (1.5) | 65/4571 (1.4) | 0.94 (0.67-1.32) | .72 | 11/4581 (0.2) | 14/4622 (0.3) | 1.28 (0.58-2.81) | .55 |

| CHANCE | 44/2312 (1.9) | 33/2384 (1.4) | 0.72 (0.46-1.14) | .16 | 6/2305 (0.3) | 1/2362 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.02-1.32) | .09 |

| POINT | 23/2158 (1.1) | 32/2187 (1.5) | 1.36 (0.80-2.33) | .26 | 5/2276 (0.2) | 13/2260 (0.6) | 2.63 (0.94-7.40) | .07 |

| 0-90 d | 458/5035 (9.1) | 328/5016 (6.5) | 0.70 (0.61-0.81) | <.001 | 18/5035 (0.4) | 30/5016 (0.6) | 1.59 (0.88-2.86) | .12 |

Abbreviations: CHANCE, Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events; POINT, Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke.

Major ischemic events included ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from ischemic vascular causes.

Adjusted for trial, sex, age, race, history of congestive heart failure, known atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or previous smoking status, qualifying event, and time to randomization, with study site as a random-effect variable in the model.

Although not statistically significant, clopidogrel-aspirin treatment numerically increased the risk of major hemorrhage both within the first 21 days after randomization (16 of 5016 [0.3%] vs 7 of 5035 [0.1%]; adjusted HR, 2.11 [95% CI, 0.86-5.17]; P = .10) and from day 22 to day 90 (14 of 4622 [0.3%] vs 11 of 4581 [0.2%]; adjusted HR, 1.28 [95% CI, 0.58-2.81]; P = .55; Table 2). Separate analyses showed that clopidogrel-aspirin therapy numerically reduced the risk of major hemorrhage in CHANCE (1 of 2362 [0.04%] vs 6 of 2305 [0.3%]; adjusted HR, 0.16 [95% CI, 0.02-1.32]; P = .09) and numerically increased the risk of major hemorrhage in POINT (13 of 2260 [0.6%] vs 5 of 2276 [0.2%]; adjusted HR, 2.63 [95% CI, 0.94-7.40]; P = .07) from day 22 to day 90 (P = 0.02 for interaction; Table 2).

In analyses of net clinical benefit, clopidogrel-aspirin had a positive net benefit both in the total period of 90 days and within the first 21 days and a negligible net benefit from day 22 to day 90, regardless of whether the weight of a major hemorrhage was chosen to be between 0.5-fold to 1.2-fold that of a major ischemic event (Table 3). Separate analyses showed a positive net benefit in CHANCE but a negative net benefit in POINT from day 22 to day 90. A sensitivity analysis adding minor hemorrhage with a weight of 0.1 to 0.5 in calculating the net benefit showed similar results (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Net Clinical Benefita.

| Weight | Events, No. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0-21 d | 22-90 d | |||

| Total | CHANCE Data Only | POINT Data Only | |||

| 0.5 | 124 | 123.5 | 0.5 | 13.5 | −13 |

| 0.6 | 122.8 | 122.6 | 0.2 | 14 | −13.8 |

| 0.7 | 121.6 | 121.7 | −0.1 | 14.5 | −14.6 |

| 0.8 | 120.4 | 120.8 | −0.4 | 15 | −15.4 |

| 0.9 | 119.2 | 119.9 | −0.7 | 15.5 | −16.2 |

| 1.0 | 118 | 119 | −1 | 16 | −17 |

| 1.1 | 116.8 | 118.1 | −1.3 | 16.5 | −17.8 |

| 1.2 | 115.6 | 117.2 | −1.6 | 17 | −18.6 |

Abbreviations: CHANCE, Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events; POINT, Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke.

Net clinical benefit was calculated as net benefit = (major ischemic event aspirin group − major ischemic event clopidogrel-aspirin group) − weight major hemorrhage × (major hemorrhage clopidogrel-aspirin group − major hemorrhage aspirin group). The weight accounts for the effects of a major hemorrhage compared with a major ischemic event (including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from ischemic vascular causes).

Discussion

In this pooled analysis of individual patient–level data from the CHANCE and POINT trials, we found that clopidogrel-aspirin started within 24 hours of the event significantly reduced the risk of major ischemic events without increasing the risk of major hemorrhage at 90 days in patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA. Major ischemic events prevented by clopidogrel-aspirin mostly occurred within the first 21 days after randomization. A clear net clinical benefit of clopidogrel-aspirin was observed during the first 3 weeks of treatment.

The efficacy of dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention in minor stroke and TIA was observed both in the CHANCE and POINT trials.1,2 A recent comparative effectiveness analysis in Korea also indicated that dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel-aspirin was associated with reduced stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death during 3 months after minor noncardioembolic ischemic stroke who met the CHANCE trial eligibility criteria.7 A recent meta-analysis that combined data from POINT, CHANCE, and the pilot trial Fast Assessment of Stroke and TIA to Prevent Early Recurrence (FASTER),8 using the published survival curves, also indicated that dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel-aspirin for a duration of 21 days (and possibly 10 days) was associated with a reduction in stroke recurrence among patients with minor stroke or TIA.5 Recently, several guidelines recommend early, short-term dual antiplatelet therapy for minor stroke or high-risk TIA,9,10,11 whereas others indicate it as an option12 or do not recommend it.13 The BMJ recently produced a strong rapid recommendation of initiating clopidogrel-aspirin within 24 hours of the symptoms onset and continuing for 10 to 21 days for patients with minor stroke or high-risk TIA.14 This pooled analysis of individual patient–level data provides additional support for recommending dual antiplatelet therapy for patients with minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA over a range of settings and populations. In this study, a potential reduction of major ischemic events was still observed for dual antiplatelet therapy from day 11 to day 21; however, it did not reach significance because of low event rates (25 of 4622 [0.5%] vs 34 of 4524 [0.8%]; adjusted HR, 0.72; [95% CI, 0.43-1.22]; P = .22; power, 24.2%).

The risk of bleeding was a major concern when dual antiplatelet therapy was administered in patients with ischemic stroke or TIA in clinical practice.15 Although similar efficacy was observed, the POINT trial also found a significant increase in the risk of major hemorrhage with clopidogrel-aspirin compared with aspirin alone, which was not found in the CHANCE trial.1,2 A longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (90 days in the POINT trial vs 21 days in the CHANCE trial) and differences in the metabolism of clopidogrel in Asian persons vs non-Asian persons are possible explanations for the difference.3 Previous time-course analyses of the CHANCE trial indicated that the net benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with minor stroke or TIA might be limited to the first 2 weeks.6 A recent meta-analysis indicated that short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (within 1 month) is more effective and equally safe compared with aspirin alone in patients with acute ischemic stroke or TIA.16 Another recent meta-analysis based on published data, mainly from CHANCE and POINT, also indicated that discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy within 21 days and possibly as early as 10 days might maximize benefit and minimize harms in patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA.5 The present pooled analysis shows that the benefits of clopidogrel-aspirin are realized in the first 21 days of treatment and not afterwards, providing further support for a 21-day duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. The inclusion of patients from different settings and populations, and the consistency of results between the 2 trials suggest that the findings are generalizable to a broad range of patients with minor stroke or TIA.

This analysis distinguishes itself from previous studies by using individual patient–level data of the 2 large-scale randomized clinical trials focused on clopidogrel-aspirin treatment in patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA. Although previous meta-analyses have been performed,5,16,17,18 they did not focus on minor stroke or TIA, the specific population most likely to benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy,16,17,18 or they only used study-level data.5,16,17,18 Pooled analyses of individual patient–level data may provide the least biased and most reliable method of addressing clinical questions that have not been satisfactorily resolved by individual clinical trials with adjustment for potential covariates.19 Another strength of this analysis is that it provides a comprehensive time-course analysis of risks and benefits of dual antiplatelet therapy for minor stroke or TIA. Because of the small number of major hemorrhages, previous time-course analysis of the CHANCE trial was based on the risk of any bleeding.6 Although mild bleeding events might also have clinical significance,6 most mild bleeding is reversible, and major or severe bleeding is the main clinical concerns when dual antiplatelet therapy is administered in clinical practice.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, bias may exist because of differences in the trial designs, such as in the definitions of hemorrhage. However, the variance in resulting estimates was modeled by the inclusion of random effects in the mixed-effects models, which should appropriately widen CIs. Second, the 21-day time course of use of combined clopidogrel-aspirin in CHANCE limits the utility of CHANCE data for drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of combined antiplatelet therapy after 21 days. Third, the present study failed to address the risks and benefits of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients because of different causative mechanisms of the index cerebrovascular event. It is possible that patients with different causative subtypes of ischemic stroke and TIA may respond differently to dual antiplatelet therapy.20,21 The 2 original trials did not collect data on event subtypes; however, both enrolled populations heterogeneous for causative mechanism and excluded major cardioembolic causes. Fourth, although sensitivity analyses of net clinical benefit were performed assuming a large range of weights for hemorrhage relative to ischemic events, there is no established weight of a hemorrhage event compared with a major ischemic event. Fifth, this pooled analysis was anticipated during the planning of the CHANCE and POINT trials, but no statistical analysis plan was established prior to trial completion.

Conclusions

This pooled analysis of individual patient–level data found that early, short-term treatment with clopidogrel-aspirin reduced the risk of major ischemic events without increase in the risk of major hemorrhage at 90 days in patients with minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA. The main net clinical benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy occurred within the first 3 weeks.

eFigure 1. Hazard ratios for the primary efficacy outcome in prespecified subgroups

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analysis of net clinical benefit considering minor hemorrhage

eTable 1. Characteristics of the CHANCE and POINT trials

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of the patients

eTable 3. Time course distribution of major ischemic events and major hemorrhages by treatment assignment

References

- 1.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. ; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grotta JC. Antiplatelet therapy after ischemic stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):291-292. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1806043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GUSTO investigators An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(10):673-682. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309023291001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao Q, Tampi M, O’Donnell M, Foroutan F, Siemieniuk RA, Guyatt G. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for acute minor ischaemic stroke or high risk transient ischaemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k5108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y, Jing J, Chen W, et al. ; CHANCE investigators . Risks and benefits of clopidogrel-aspirin in minor stroke or TIA: time course analysis of CHANCE. Neurology. 2017;88(20):1906-1911. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JT, Park MS, Choi KH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of aspirin and clopidogrel versus aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2018;50(1):A118022691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM; FASTER Investigators . Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):961-969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Liu M, Pu C. 2014 Chinese guidelines for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(3):302-320. doi: 10.1177/1747493017694391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulanger JM, Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations for acute stroke management: prehospital, emergency department, and acute inpatient stroke care, 6th Edition, update 2018. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(9):949-984. doi: 10.1177/1747493018786616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroke Foundation Clinical guidelines for stroke management 2017. https://informme.org.au/en/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management-2017. Published 2017. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 13.Royal College of Physicians National clinical guideline for stroke: prepared by the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, 5th edition. https://www.strokeaudit.org/SupportFiles/Documents/Guidelines/2016-National-Clinical-Guideline-for-Stroke-5t-(1).aspx. Published 2016. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 14.Prasad K, Siemieniuk R, Hao Q, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for acute high risk transient ischaemic attack and minor ischaemic stroke: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;363:k5130. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreiro JL, Sibbing D, Angiolillo DJ. Platelet function testing and risk of bleeding complications. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1128-1135. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman H, Khan SU, Nasir F, Hammad T, Meyer MA, Kaluski E. Optimal duration of aspirin plus clopidogrel after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2019;50(4):947-953. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Zhou M, Zhong X, et al. Dual versus mono antiplatelet therapy for acute non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2018;3(2):107-116. doi: 10.1136/svn-2018-000168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding L, Peng B. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy in the elderly for stroke prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(10):1276-1284. doi: 10.1111/ene.13695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart LA, Parmar MK. Meta-analysis of the literature or of individual patient data: is there a difference? Lancet. 1993;341(8842):418-422. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93004-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA; SPS3 Investigators . Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):817-825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing J, Meng X, Zhao X, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke with different infarction patterns: subgroup analysis of the CHANCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(6):711-719. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Hazard ratios for the primary efficacy outcome in prespecified subgroups

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analysis of net clinical benefit considering minor hemorrhage

eTable 1. Characteristics of the CHANCE and POINT trials

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of the patients

eTable 3. Time course distribution of major ischemic events and major hemorrhages by treatment assignment