Key Points

Question

Which electronic health record (EHR) design and use factors are associated with clinician stress and burnout?

Findings

In this survey study of 282 clinicians, clinician stress and burnout were associated with 7 EHR design and use factors. These 7 plus 2 other design and use factors collectively accounted for a modest amount of the variance in stress (12.5%) and burnout (6.8%); models incorporating other work conditions (such as chaotic work atmosphere and workload control) accounted for considerably more of the variance in stress (58.1%) and burnout (36.2%).

Meaning

While EHR design and use factors may appropriately be targeted by health systems and EHR designers to address stress and burnout, other non-EHR issues, especially clinician work conditions, appear to play a substantial role in adverse clinician outcomes.

This survey study determines which electronic health record (EHR) design and use factors are associated with clinician stress and burnout and identifies other sources that contribute to this problem.

Abstract

Importance

Many believe a major cause of the epidemic of clinician burnout is poorly designed electronic health records (EHRs).

Objectives

To determine which EHR design and use factors are associated with clinician stress and burnout and to identify other sources that contribute to this problem.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study of 282 ambulatory primary care and subspecialty clinicians from 3 institutions measured stress and burnout, opinions on EHR design and use factors, and helpful coping strategies. Linear and logistic regressions were used to estimate associations of work conditions with stress on a continuous scale and burnout as a binary outcome from an ordered categorical scale. The survey was conducted between August 2016 and July 2017, with data analyzed from January 2019 to May 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinician stress and burnout as measured with validated questions, the EHR design and use factors identified by clinicians as most associated with stress and burnout, and measures of clinician working conditions.

Results

Of 640 clinicians, 282 (44.1%) responded. Of these, 241 (85.5%) were physicians, 160 (56.7%) were women, and 193 (68.4%) worked in primary care. The most prevalent concerns about EHR design and use were excessive data entry requirements (245 [86.9%]), long cut-and-pasted notes (212 [75.2%]), inaccessibility of information from multiple institutions (206 [73.1%]), notes geared toward billing (206 [73.1%]), interference with work-life balance (178 [63.1%]), and problems with posture (144 [51.1%]) and pain (134 [47.5%]) attributed to the use of EHRs. Overall, EHR design and use factors accounted for 12.5% of variance in measures of stress and 6.8% of variance in measures of burnout. Work conditions, including EHR use and design factors, accounted for 58.1% of variance in stress; key work conditions were office atmospheres (β̂ = 1.26; P < .001), control of workload (for optimal control: β̂ = −7.86; P < .001), and physical symptoms attributed to EHR use (β̂ = 1.29; P < .001). Work conditions accounted for 36.2% of variance in burnout, where challenges included chaos (adjusted odds ratio, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.10-1.75; P = .006) and physical symptoms perceived to be from EHR use (adjusted odds ratio, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.48-2.74; P < .001). Coping strategies were associated with only 2.4% of the variability in stress and 1.7% of the variability in burnout.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although EHR design and use factors are associated with clinician stress and burnout, other challenges, such as chaotic clinic atmospheres and workload control, explain considerably more of the variance in these adverse clinician outcomes.

Introduction

The adoption of the electronic health record (EHR) has occurred alongside the dramatic and troubling rise in clinician stress and burnout.1,2,3 This association has fueled the debate over the extent to which EHRs are associated with the epidemic of clinician stress and burnout. Technostress (ie, the stress related to technological tools in numerous industries) is real,4 but the degree to which it is a factor in medicine is largely unknown.

The introduction of EHRs has resulted in shifting many clerical tasks to clinicians (eg, billing, coding, and quality control) as well as creating new tasks to be performed during clinical encounters (eg, data entry, computerized decision support, computerized order entry, and electronic prescribing). These new tasks have increased the cognitive and physical load on the clinician in many ways.5,6 For example, e-prescribing, which has benefits, has also created an additional burden by requiring clinicians to know where to route prescriptions at the time they prescribe. This may be a relatively small burden, but repeated multiple times per day and added to the myriad other tasks shifted to clinicians, these technology-enabled tasks have considerably increased clinician workload. In fact, an entirely new medical scribe industry has arisen in order to ameliorate the additional workload.7

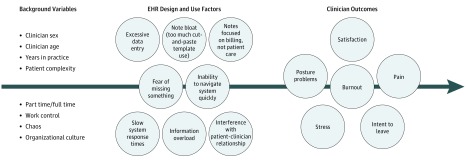

We designed this study (Minimizing Stress, Maximizing Success of the Electronic Health Record) to identify the relative contribution of aggregated EHR burdens compared with other burdens (ie, workplace chaos, control of workload) associated with clinician stress and burnout. This work is based on a conceptual framework derived from prior work (Figure).8 Our hypothesis was that EHR-associated stress adds to overall stress and could lead to burnout—which may play a role in the quality of patient care. In this study, we aim to understand which EHR design and use factors are associated with stress and burnout. The potentially challenging EHR design and use factors included in the survey instrument were identified through physician focus groups conducted in the first phase of the study.9 The design and use factors studied were intentionally limited to those over which clinicians and their institutions might have some control. This in no way minimizes other societal factors, such as governmental regulation and malpractice, that could be associated with clinician stress and burnout.10,11,12 This survey phase of our study quantifies the association of these EHR design and use factors with clinician stress and burnout to address the following questions: (1) what specific EHR design and use factors are most strongly associated with clinician stress and burnout? (2) What amount of overall stress and burnout is associated with EHRs? And, (3) what coping strategies or organizational solutions did respondents feel are important in addressing stress and burnout?

Figure. Conceptual Framework of Association of Work Conditions and Electronic Health Record (EHR) Design and Use Factors With Clinician Outcomes.

Methods

Identification of Challenging EHR Design and Use Factors

The methods for this study have been previously reported.9 In brief, physician focus groups at 3 institutions (Stanford Hospital and Clinics, Stanford, California; University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; and Centura Health Physician Group, Westminster, Colorado) identified EHR design and use factors that were perceived as successful and those that were associated with user stress, burnout, or unintended physical symptoms. We also identified commonly used coping strategies by the clinicians.

Survey and Sampling

The EHR design and use factors identified in prior clinician focus groups informed the design of the survey instrument, which is freely available.13 The instrument included questions from previously validated instruments to measure stress, burnout, and other challenges identified by Motowidlo,14 the Physician Worklife Survey,15 the Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome Study,16 and the Healthy Work Place Study.17,18 Questions also focused on workplace characteristics such as workload control19 and work atmosphere (a single item measure from the Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome Study)20 as well as patient complexity and organizational culture, including value alignment between leaders and clinicians. This survey study complied with the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.

The study survey instrument was pilot tested on 10 clinicians at Hennepin County Medical Center (Minneapolis, Minnesota). We then deployed the finalized instrument in 2 waves at the 3 focus group sites from August 9, 2016, through July 7, 2017. The institutional review boards at all participating institutions approved the study, and completing the survey was considered providing consent.

We used REDCap version 8.10.7 (Vanderbilt University) to deploy an electronic version of the instrument. Nonresponders to the REDCap electronic survey were mailed paper instruments. The electronic instrument used continuous slider bars for respondents to indicate a score from 0 to 100, where 0 indicated not at all and 100 indicated to a great extent. The paper instrument used Likert scales mapped to the scale of 0 to 100 for analysis (ie, 1, not at all, mapped to 15; 2 mapped to 40; 3 mapped to 60; and 4, to a great extent, mapped to 85).

The survey’s design attempted to determine the following: (1) perceived EHR successes, (2) EHR design and use factors associated with clinician stress and burnout, (3) perceived adverse personal outcomes (eg pain or anxiety), (4) things that could improve the EHR experience (eg, greater staff support, scribes, or fewer clicks per task), and (5) coping strategies (eg, exercise or setting boundaries). We sampled clinicians (physicians and advanced practice clinicians, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants) at 3 institutions from 5 disciplines: general internal medicine, medical subspecialties, general pediatrics, pediatric subspecialties, and family medicine. We excluded residents, as we thought they could have dissimilar experiences of stress and burnout than practicing clinicians. We determined respondent stress levels using the 4-item validated measures from Motowidlo,14 a continuous measure that ranges from 4 to 20, and burnout using the single-item validated measure from the Physician Worklife Study, in which a score of 3 or more indicates burnout.21 While a binary approach to burnout has been controversial,22,23 this measure has been used and validated in many settings and among thousands of respondents for 20 years, and it is associated with adverse work conditions and adverse clinician outcomes, such as intent to leave the practice. We ran additional analyses using the 5-choice measure of burnout as an ordered categorical (as opposed to binary) outcome and found no substantive differences between the 2 methods.

Statistical Analysis

Answers to survey questions were analyzed as standard summary statistics. We reported continuous variables as mean and SD and categorical variables as number of respondents and percentages of total sample.

Linear regression was used to determine the association of focus group–identified variables (eg, work conditions, EHR design and use factors, and coping strategies) with clinician-reported stress, which we scored according to the Motowidlo 4-item measure,14 and burnout. β̂ was used to estimate the magnitude and direction of association, and it was calculated using the least-square estimation technique. We used logistic regression with stepwise selection, which is a combination of the forward and backward selection techniques, to estimate the association of focus group–identified variables with the odds of clinician-reported burnout, which we measured as a binary outcome based on a single question (with burnout representing endorsement of any choice with the word burnout in it).14 We used construct variables created to summarize the associations of variables within the same domain with stress and burnout. To develop the final regression model for stress, variables with R2 greater than 0.10 in the univariate analysis or that were determined to be of special interest were considered candidate variables for the multivariable model. The final logistic regression model for burnout used a stepwise selection technique, which was determined to be the most comprehensive method because it combines both forward and backward selection. To justify lumping together different types of clinicians and specialties, 1-way analysis of variance was used to examine if statistically significant differences existed in the means of outcome measures across clinician type (ie, MD, DO, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) or specialty (ie, primary care, nonprocedural specialist, or procedural specialist). Diagnostics done on the regression and logistic models were the Breusch-Pagan test for constant variance and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fit, noting that P > .05 indicates having constant variance for the regression model and correct fit for the logistic model respectively. (These showed that the models were well calibrated.) Finally, we performed a statistical factor analysis using the varimax rotation method on 9 EHR design and use items to summarize the association of EHRs with stress and burnout. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) for all analyses. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, and all tests were 2-tailed.

Results

Sample and Work-Life Balance Description

Between August 2016 and July 2017, we surveyed 640 clinicians from 3 institutions, with 282 (44.1%) responding (208 [73.8%] electronically and 74 [26.2%] on paper); 160 (56.7%) were women, 241 (85.5%) were physicians (MDs and DOs), and 193 (68.4%) worked in primary care (Table 1). Overall, 256 respondents (90.8%) answered at least 95 of the 105 survey questions. The 1-way analysis of variance showed no significant difference in mean (SD) burnout between clinician types (DO, 2.33 [0.52]; MD, 2.54 [0.94]; nurse practitioner, 2.14 [0.53]; physician assistant, 2.45 [0.94]; P = .42) or between practice types (primary care, 2.51 [0.52]; nonprocedural specialist, 2.48 [0.82]; procedural specialist 2.59 [0.76]; P = .86). Therefore, neither of these components was controlled for in the analysis. Most participants noted stressful work conditions: 210 (74.5%) reported time pressure for documentation, and 170 (60.2%) spent moderately high or excessive time on the EHR at home (Table 1). Overall, 142 (50.4%) felt they had insufficient personal time, and 134 (47.5%) reported having minimal coverage for their EHR inboxes when needed. Only 95 (33.7%) reported that their practices emphasized work-life balance, while 215 (76.2%) said that productivity was overemphasized. Half (140 [49.6%]) reported marginal or poor control over workload, and 143 (50.7%) judged their office atmospheres as chaotic or tending toward chaotic. Almost half (127 [45.0%]) described symptoms of burnout, and 117 (41.5%) indicated they were moderately to definitely likely to leave their practices within 2 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Respondent Demographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50 (11) |

| NR | 5 (1.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 118 (41.8) |

| Female | 160 (56.7) |

| NR | 46 (16.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic, any race | 30 (10.6) |

| White non-Hispanic | 191 (67.7) |

| Asian | 43 (15.3) |

| Other or NRa | 18 (6.4) |

| Clinician type | |

| MD | 241 (85.5) |

| PA | 20 (7.1) |

| NP | 14 (5.0) |

| DO | 6 (2.1) |

| NR | 1 (0.4) |

| Practice type | |

| Primary care | 193 (68.4) |

| Nonprocedural specialist | 53 (18.8) |

| Procedural specialist | 28 (9.9) |

| Multiple practice types | 5 (1.8) |

| Not specified | 45 (13.0) |

| NR | 3 (1.1) |

| Roles | |

| Full time | 226 (80.1) |

| Part time | 54 (19.1) |

| NR | 2 (0.7) |

| % of patients, mean (SD) [NR] | |

| With ≥3 complex medical problems | 64.4 (27.2) [0] |

| With complex psychosocial problems | 50.4 (26.8) [1] |

| Non-English speaking | 18.8 (18.4) [0] |

| Likelihood of leaving practice in 2 y | |

| None | 75 (26.6) |

| Slight | 89 (31.6) |

| Moderate | 59 (20.9) |

| Likely | 36 (12.8) |

| Definitely | 22 (7.8) |

| NR | 1 (0.4) |

| Enough time for personal and family life | |

| Strongly disagree | 50 (17.7) |

| Disagree | 92 (32.6) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 54 (19.2) |

| Agree | 78 (27.7) |

| Strongly agree | 8 (2.8) |

| NR | 0 |

| Inbox coverage when out of office | |

| Slight or none | 62 (22.0) |

| Some | 72 (25.5) |

| Moderate | 78 (27.7) |

| Great | 68 (24.1) |

| NR | 2 (0.7) |

| Enough time for charting at work | |

| Poor | 86 (30.5) |

| Marginal | 124 (44.0) |

| Satisfactory | 51 (18.1) |

| Good | 17 (6.0) |

| Optimal | 1 (0.4) |

| NR | 3 (1.1) |

| Time spent on EHR at home | |

| Excessive | 61 (21.6) |

| Moderately high | 109 (38.7) |

| Satisfactory | 20 (7.1) |

| Modest | 40 (14.2) |

| Minimal or none | 52 (18.4) |

| NR | 0 |

| Workplace emphasizes work-life balance | |

| Slight or none | 74 (26.2) |

| Some | 113 (40.1) |

| Moderate | 77 (27.3) |

| Great | 18 (6.4) |

| NR | 0 |

| Workplace emphasizes productivity | |

| Slight or none | 11 (3.9) |

| Some | 56 (19.9) |

| Moderate | 131 (46.5) |

| Great | 84 (29.8) |

| NR | 0 |

| Control over workload | |

| Poor | 46 (16.3) |

| Marginal | 94 (33.3) |

| Satisfactory | 94 (33.3) |

| Good | 44 (15.6) |

| Optimal | 4 (1.4) |

| NR | 0 |

| Office atmosphere | |

| Calm | 5 (1.8) |

| Tending to be busy | 15 (5.3) |

| Busy, but reasonable | 77 (27.3) |

| Tending to be chaotic | 110 (39.0) |

| Hectic, chaotic | 33 (11.7) |

| NR | 42 (14.9) |

| Symptoms of burnout | |

| No symptoms | 28 (9.9) |

| Occasionally stressed but not burned out | 126 (44.7) |

| Burning out with ≥1 symptom | 94 (33.3) |

| Burnout symptoms will not go away | 22 (7.8) |

| Completely burned out and wonder if I can go on | 11 (3.9) |

| NR | 1 (0.4) |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; NP, nurse practitioner; NR, no response; PA, physician assistant.

Other category included Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, or other.

Success and Challenges of the EHR

The EHR successes participants identified included the ability to message colleagues electronically (197 [69.9%]), access to the EHR from home (213 [75.5%]), and the opportunity to share results with patients (136 [48.2%]). The most troublesome EHR design and use factors reported were excessive data entry requirements (245 [86.9%]), “note bloat” (unnecessarily long cut-and-pasted progress notes; 212 [75.2%]), inaccessible information from other institutions (206 [73.1%]), notes geared toward billing rather than patient care (206 [73.1%]), problems with work-life balance (178 [63.1%]), and 2 physical items that respondents attributed to EHR use: posture issues (144 [51.1%]) and pain (134 [47.5%]).

Association of EHR Use and Design Factors With Stress and Burnout

The EHR design and use factors significantly associated with high clinician stress were information overload (β̂ = 0.37; P < .001), slow system response times (β̂ = 0.42; P < .001), excessive data entry (β̂ = 0.43; P < .001), inability to navigate the system quickly (β̂ = 0.38; P < .001), note bloat (β̂ = 0.24; P = .01), fear of missing something (β̂ = 0.34; P < .001), interference with the patient-clinician relationship (β̂ = 0.29; P < .01), and notes geared toward billing (β̂ = 0.41; P < .001) (Table 2). In our analyses, burnout was used as a dichotomous as well as an ordered categorical variable, and there were no substantive differences between the 2 approaches. All of the previously listed EHR design and use factors were independently associated with burnout except fear of missing something. These factors collectively accounted for 12.5% and 6.8% of the variance in stress and burnout (as a binary outcome), respectively. Physical symptoms attributed to EHR use increased odds of burnout (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.01; 95% CI, 1.48-2.75; P < .001)

Table 2. Design and Use Factors of EHRs Associated With Stress and Burnout.

| Design and Use Factora | Stress, Continuous | Burnout, Binary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β̂b | P Value | R2, %c | OR (95% CI) | P Value | AUC | R2, %c | |

| How challenging are the following aspects of your EHR? | |||||||

| Information overload | 0.37 | <.001 | 6.2 | 1.18 (1.06-1.30) | .002 | 0.61 | 5.1 |

| Lack of access to patient information from multiple institutions | 0.14 | .08 | 1.1 | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) | .85 | 0.50 | 0.1 |

| Slow system response times | 0.42 | <.001 | 8.9 | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) | .01 | 0.59 | 3.2 |

| Excessive data entry | 0.43 | <.001 | 6.8 | 1.24 (1.10-1.40) | <.001 | 0.65 | 6.3 |

| Inability to navigate the system quickly | 0.38 | <.001 | 6.7 | 1.12 (1.02-1.24) | .02 | 0.59 | 2.7 |

| Note bloat, ie, progress notes too complex to read | 0.24 | .01 | 2.4 | 1.16 (1.04-1.28) | .006 | 0.60 | 3.7 |

| Fear of missing something | 0.34 | <.001 | 5.4 | 1.06 (0.96-1.17) | .22 | 0.55 | 0.8 |

| Interference with the patient-clinician relationship | 0.29 | .002 | 3.7 | 1.14 (1.03-1.27) | .01 | 0.60 | 3.3 |

| Notes geared toward billing not patient care | 0.41 | <.001 | 8.8 | 1.26 (1.14-1.40) | <.001 | 0.67 | 10.6 |

| EHR challenges construct variable, per 10-unit increased | 0.80 | <.001 | 12.5 | 1.35 (1.15-1.58) | <.001 | 0.64 | 6.8 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiving operating characteristic curve; EHR, electronic health record; OR, odds ratio.

Each factor has the possible value of 0 to 100, where 0 indicates not challenging at all and 100 indicates challenging to a great extent.

Indicates the rate of change in the EHR challenges construct variable per 10-unit increase in the independent variable.

Percentage of variability in the primary outcome explained by the design and use factor.

Created by averaging the response values for all questions yielding a possible range from 0 to 100 for the construct score.

Other Factors Associated With Stress and Burnout

Factors not related to EHRs associated with high levels of variance in stress were office atmospheres (β̂ = 1.26; P < .001), control of workload (for optimal control: β̂ = −7.86; P < .001), time for personal and family life (for disagree: β̂ = −2.30; P < .001), time for documentation at work (for satisfactory: β̂ = −2.93; P < .001), value alignment with leaders (for agree strongly: β̂ = −4.73; P < .001), professional and personal life balance (β̂ = −1.56; P < .001), physical symptoms attributed to EHR use (β̂ = 1.29; P < .001) and hours worked per week (β̂ = 0.78; P < .001). Within a multivariable linear regression model (Table 3), these variables, along with the EHR design and use factors listed in Table 2, consequences of EHR use, and EHR use at home, accounted for 58.1% of variance in clinician-reported stress and 36.2% of variance in burnout (Table 4). A chaotic work environment increased the odds of burnout (aOR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.10-1.75; P = .006).

Table 3. Univariate and Multivariable Models for Stress.

| Factor | Univariate Models | Multivariable Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted β̂a | P Value | R2, %b | Adjusted β̂a | P Value | |

| EHR challenges construct variable, per 10-unit increase | 0.80 | <.001 | 12.5 | 0.13 | .36 |

| Office atmosphere, per 10-unit increasec | 1.26 | <.001 | 34.3 | 0.66 | <.001 |

| Workload control | NA | <.001 | 28.7 | NA | .01 |

| Poor | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Marginal | −1.40 | .01 | NA | 0.22 | .71 |

| Satisfactory | −4.25 | <.001 | NA | −1.06 | .14 |

| Good | −5.16 | <.001 | NA | −1.18 | .17 |

| Optimal | −7.86 | <.001 | NA | −5.48 | .004 |

| Work schedule leaves enough time for my personal and family life | NA | <.001 | 24.0 | NA | .10 |

| Strongly disagree | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Disagree | −2.30 | <.001 | NA | −0.05 | .94 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | −4.62 | <.001 | NA | −1.69 | .03 |

| Agree | −4.54 | <.001 | NA | −5.73 | .49 |

| Strongly agree | −6.23 | <.001 | NA | −6.26 | .67 |

| Compensated roles | NA | .14 | 0.78 | NA | .74 |

| Part-time | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Full-time | 0.83 | .14 | NA | −0.21 | .74 |

| Sufficiency of time for documentation at work | NA | <.001 | 12.69 | NA | .50 |

| Poor | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Marginal | −1.99 | <.001 | NA | −0.53 | .32 |

| Satisfactory | −2.93 | <.001 | NA | −0.58 | .43 |

| Good | −4.48 | <.001 | NA | −0.16 | .90 |

| Optimal | −2.72 | .43 | NA | 3.70 | .21 |

| Professional values are well aligned with those of departmental or clinical leaders | NA | <.001 | 11.45 | NA | .62 |

| Strongly disagree | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Disagree | −2.33 | .03 | NA | −1.12 | .20 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | −2.93 | .005 | NA | −1.05 | .26 |

| Agree | −4.44 | <.001 | NA | −1.34 | .11 |

| Agree strongly | −4.73 | <.001 | NA | −1.09 | .29 |

| Professional and personal life balance, per 1-unit increase | −1.56 | <.001 | 14.06 | −0.40 | .12 |

| Consequences construct variable, per 100-unit increased | 1.29 | <.001 | 22.53 | 0.69 | <.001 |

| Amount of time spent on EHR at home | NA | <.001 | 8.26 | NA | .58 |

| Excessive | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Moderately high | −2.18 | <.001 | NA | −0.10 | .86 |

| Satisfactory | −3.08 | <.001 | NA | −0.92 | .37 |

| Modest | −2.86 | <.001 | NA | 0.50 | .51 |

| Minimal or none | −2.51 | <.001 | NA | 0.54 | .48 |

| Total average hours worked per week, per 10-unit increase | 0.78 | <.001 | 8.25 | −0.01 | .96 |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; NA, not applicable.

Indicates the rate of change in the EHR challenges construct variable by 1-, 10-, or 100-unit increase in the independent variable when the independent variable is continuous. When the independent variable is categorical, β̂ indicates the rate of change in stress from 1 category relative to the reference category. Adjusted β̂ assumes that all other variables in the model are held constant.

Percentage of variability in the primary outcome explained by the factor for the univariate model. R2 in the primary outcome explained by the set of factors for the multivariable model was 58.1.

The values of atmosphere range from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating calm and 100 indicating hectic or chaotic.

The values of the consequences construct range from 0 to 600, with 0 indicating not at all and 600 indicating to a great extent. It is composed from the total of the responses of 6 variables (pain, headache or eye strain, posture problems, sleep difficulties, anxiety or depression, and interference with work-life balance).

Table 4. Univariate and Multivariable Models for Burnout.

| Factor | Univariate Models | Multivariable Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value | AUCa | R2, %b | Adjusted OR (95 %CI) | P Value | |

| EHR challenges construct variable, per 10-unit increasec | 1.35 (1.15-1.59) | <.001 | 0.65 | 6.8 | 0.91 (0.71-1.17) | .48 |

| Race/ethnicity | NA | >.99 | 0.51 | 0.02 | NA | .19 |

| White Non-Hispanic | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Asian | 0.99 (0.51-1.93) | .93 | NA | NA | 0.47 (0.17-1.30) | .83 |

| Hispanic, any race | 0.91 (0.42-1.99) | .87 | NA | NA | 0.37 (0.12-1.15) | .45 |

| Other or unknownd | 0.96 (0.36-2.53) | .98 | NA | NA | 0.39 (0.09-1.63) | .63 |

| Office atmosphere, per 10-unit increasee | 1.73 (1.42-2.11) | <.001 | 0.72 | 20.0 | 1.39 (1.10-1.75) | .006 |

| Consequences construct variable, per 100-unit increasef | 1.94 (1.56-2.40) | <.001 | 0.73 | 21.2 | 2.01 (1.48-2.74) | <.001 |

| Primary care practice type | NA | .15 | 0.54 | 1.0 | NA | .19 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 0.68 (0.41-1.14) | .15 | NA | NA | 0.58 (0.26-1.31) | .19 |

| Procedural specialist practice type | NA | .04 | 0.54 | 2.1 | NA | .34 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 2.21 (1.04-4.72) | .04 | NA | NA | 1.72 (0.57-5.21) | .34 |

| Complex patient construct variable, per 50-unit increaseg | 1.20 (0.94-1.53) | .14 | 0.55 | 1.1 | 0.96 (0.68-1.36) | .83 |

| Importance construct variable, per 1-unit increaseh | 0.83 (0.76-0.91) | <.001 | 0.65 | 7.5 | 0.91 (0.80-1.03) | .14 |

| No. of years since completing training, per 1-unit increase | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .02 | 0.58 | 2.8 | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | .20 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiving operating characteristic curve; EHR, electronic health record; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Accuracy rate of the model as it determines the discriminatory power of its estimation. For the multivariable model, the AUC was 0.81.

Percentage of variability in the primary outcome explained by the factor for the univariate models. R2 in the primary outcome explained by the set of factors for the multivariable model was 36.2%.

Created by averaging the response values from 9 questions yielding a possible range from 0 to 100 for the construct score.

Other category included Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, or other.

Ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating calm and 100 indicating hectic or chaotic.

Ranges from 0 to 600, with 0 indicating not at all and 600 indicating to a great extent. It is composed from the total of the responses of 6 variables (pain, headache and eye strain, posture problems, sleep difficulties, anxiety or depression, and interference with work-life balance).

Ranges from 0 to 300, with 0 indicating having a low percentage of complex patients and 300 indicating having very high percentage of complex patients. It is composed of the total of responses to 3 variables (patients with ≥3 complex medical problems, patients with complex or numerous psychosocial problems, and patients non-English speaking).

Ranges from 0 to 20, with 0 indicating a practice setting emphasizing slight or no importance and 20 indicating emphasizing great importance. It is composed from the total of responses to 5 variables (care for underserved populations, teamwork, information technology training, balancing professional and personal life, and productivity).

Coping Strategies

Coping strategies for reducing stress felt to be associated with the EHR included talking with others (194 [68.8%]), exercise (192 [68.1%]), setting work boundaries (161 [57.1%]), discussing EHR messages with others rather than pinging electronic messages back and forth (149 [52.8%]), and writing shorter notes (142 [50.4%]). As a combined variable, coping strategies accounted for only 2.4% and 1.7% of the variability in stress and burnout respectively (data not shown). Setting boundaries (β̂ = −0.02; P < .01) and taking breaks (β̂ = −0.02, P = .006) were independently associated with reductions in overall stress, while exercise (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00; P = .04) and taking breaks (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00; P = .003) were associated with reductions in the odds of burnout.

Factor Analysis of EHR Stress Items

We performed a statistical factor analysis using the varimax rotation method on the 9 EHR design and use factors listed in Table 2. We found that the first 2 statistical factors from the factor analysis accounted for 52.2% of the variability in EHR design and use items. We characterize these 2 factors as follows: (1) interference with patient care (eg, note bloat, interference with patient-clinician relationships, and notes geared toward billing) and (2) inefficient systems (eg, slow system response times, inability to navigate the system quickly, and excessive data entry). Thus, more than half of the variance in EHR issues associated with clinician stress and burnout stemmed from interference with patient care and inefficient EHR systems.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional survey of 282 clinicians from 3 health systems, we identified 7 EHR design and use factors associated with high stress and burnout. These were information overload, slow system response times, excessive data entry, inability to navigate the system quickly, note bloat, interference with the patient-clinician relationship, fear of missing something, and notes geared toward billing. While previous studies have identified several of these EHR design and use items as challenging to clinicians,9,24,25 we believe this study is the first to show an association between these factors and objectively validated stress and burnout scales.

In this study, 45.0% of participants described symptoms of burnout, consistent with the findings of the national survey by Shanafelt et al2 in which 44% of physicians reported at least 1 symptom of burnout. The amounts of variation in stress and burnout associated with the EHR design and use factors listed in Table 2 were 12.5% and 6.8%, respectively. Thus, other sources of burnout aside from the EHR (such as lack of control of workload, chaotic environments, lack of attention to work-life balance, and ineffective teamwork) will also need to be addressed as medical practices seek to reduce burnout.

Many of the identified EHR design and use factors may be remediable through a combination of improvements by EHR vendors, local improvements by information technology personnel, and training of clinicians in the clinical environment. However, some of the identified factors may require higher-level actions on the part of clinic or governmental policy makers, for example, by allowing notes to be more geared toward clinical care than billing practices. Documentation requirements for billing purposes is an EHR design characteristic associated with both stress and burnout. The length of clinical notes has essentially doubled since the enactment of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act.26 Physicians outside the United States are more likely to report satisfaction with their EHRs, where clinical documentation is significantly shorter and contains much less information in support of billing and compliance.26 The American Medical Informatics Association has recently called for a long-term strategy from the US Department of Health and Human Services to decouple clinical documentation from billing, regulatory, and administrative compliance requirements.27

Information overload may be associated with EHR design in which too much clinically unnecessary information is displayed. The aviation industry has a user interface design philosophy called quiet dark, where information is not displayed until something goes wrong or needs the pilot’s attention.28 In other words, the default state of all indicator lights is off during normal conditions. Applying this philosophy to EHR design could potentially reduce the amount of unnecessary data displayed based on particular users’ need and context, reducing the information overload problem. Arguably, the current state of EHR design is loud bright, where virtually all information, normal or otherwise, appears in relatively the same manner regardless of its importance to the clinician or patient. Although abnormal results from laboratory tests are highlighted, all normal values are typically displayed and occupy the same amount of space and are given the same prominence as abnormal results. Given the proliferation of standardized templates as a time-saving tool for data entry, the amount of unnecessary, repetitive, normal information (ie, note bloat) is increasing vs a design where an economy of information relevant to the patient’s current needs and context is used.29

The data entry problem has created the scribe movement and produced promising results, at least in terms of clinician and patient satisfaction.30 However, scribes only help with data entry during office visits and not with EHR tasks at other times and in other venues. A more comprehensive approach is to use specially trained medical assistants (MAs) to relieve the clinician from clinic tasks (eg, responding to routine in-basket messages, refilling some prescriptions per protocol, completing paperwork). Before the clinician meets the patient, the MA completes prework (eg, medication reconciliation, review of systems, documentation of chief concern, and any protocolized clinical measurements, such as peak flows or pulse oximetry). The MA scribes during the clinician encounter, and after the clinician leaves the room, the MA can review the plan of care, deliver patient education, process referral requests, and schedule follow-up appointments.31

Some of the troublesome EHR design and use factors, such as the inability to navigate the system quickly, are attributable to computer-human interaction problems. In fact, most of the current EHR user interface designs are still based on 2-dimensional paper metaphors (eg, tabs, flowsheets, tables, and forms) and do not take advantage of the potential of graphics capabilities now in the most basic computers.32 More research to determine what display metaphors beyond paper are most efficient could help. Complaints of interference with the patient-clinician relationship is evidence that clinicians are troubled by their excessive focus on the screen rather than the patient. While most studies have shown the presence of the EHR in the exam room does not adversely affect patient satisfaction,9,33,34 clinicians feel that EHRs requiring clinically irrelevant data entry take away from their relationships with their patients.35 Our study shows that this is significantly associated with clinician stress and burnout.

The proportion of clinicians reporting pain (47.5%) and posture issues (51.1%) attributed to EHR use was high. Ergonomics are rarely addressed in most clinical settings. Clinicians often must work at several workstations, with different heights and seat structures. Collaboration with employee health groups skilled at ergonomics could potentially have a substantive effect on the health outcomes of our clinician workforce.36 This is an area ripe for further quality improvement studies.

Coping strategies clinicians suggested to reduce EHR-associated stress included exercise (used by 68.1% of our sample), verbally discussing issues with other clinicians (68.8%), and setting boundaries for work while at home (57.1%). Setting boundaries, exercise, and taking breaks were significantly associated with reductions in overall stress and burnout and may be useful components to incorporate into stress reduction interventions. It is not clear how many of these strategies clinicians actually used or how effective they were at using them.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include surveying a diverse group of clinicians, including academic, community-based, and rural institutions and practices, physicians and advanced practice clinicians, and a mix of specialists and nonspecialty ambulatory care clinicians. In addition, the list of the EHR design and use factors the clinicians rated in the survey was defined by clinicians in multi-institutional focus groups.9 The survey response rate (44.1%) was reasonable for large clinician-based studies with no financial incentive. The design of the instrument included questions previously validated in studies of physicians about stress and burnout.

This study has limitations, including its cross-sectional nature and the use of self-reported metrics. One needs to consider response bias, given the 44.1% response rate. The relatively modest sample size limits validity. As respondents came from only 3 institutions, these results may not be more widely generalizable. The mapping of the paper instrument’s Likert scales to the REDCap slider bars scale may have introduced some bias. Despite using validated instruments to measure burnout and stress, the survey relied on the respondents’ own definitions. Self-reported metrics may underrepresent the numbers at risk. As Knox et al37 found, a self-defined, single-item burnout measure identified significantly fewer physicians most at risk of burning out compared with the Maslach Burnout Inventory. All respondents were grouped together for this analysis, which does not account for possible intragroup differences, such as between physicians and advanced practice clinicians.37

Conclusions

Stress and burnout associated with EHRs is prevalent and may be at least partly remediable at the local level. The issues identified in our list of EHR-associated challenges may provide designers, government regulators, and clinical leaders with targets for improvement of EHR design. Other work conditions are associated with stress and burnout in clinicians and deserve equal attention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Office-based physician electronic health record adoption. https://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/physician-ehr-adoption-trends.php. Accessed February 26, 2019.

- 2.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. . Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;S0025-6196(18)30938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. . Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarafdar M, Tu Q, Ragu-Nathan B, Ragu-Nathan T. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J Manage Inf Syst. 2007;24(1):301-328. doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222240109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinsky CA, Privitera MR. Creating a “manageable cockpit” for clinicians: a shared responsibility. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):741-742. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holden RJ. Cognitive performance-altering effects of electronic medical records: an application of the human factors paradigm for patient safety. Cogn Technol Work. 2011;13(1):11-29. doi: 10.1007/s10111-010-0141-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra-Hebert AD, Amah L, Rabovsky A, et al. . Medical scribes: how do their notes stack up? J Fam Pract. 2016;65(3):155-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. ; MEMO (Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome) Investigators . Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28-36, W6-9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, et al. . The electronic elephant in the room: physicians and the electronic health record. JAMIA Open. 2018;1(1):49-56. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooy016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brett AS. New guidelines for coding physicians’ services: a step backward. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(23):1705-1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iezzoni LI. The demand for documentation for Medicare payment. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(5):365-367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RA, Burge S, Kumar KA, Wilson J. The full scope of family physicians’ work is not reflected by current procedural terminology codes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(6):724-732. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.06.170155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, et al. MS-Squared Survey Instrument V 2.0. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ms2/3/. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- 14.Motowidlo SJ, Packard JS, Manning MR. Occupational stress: its causes and consequences for job performance. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(4):618-629. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. ; SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine . Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. Med Care. 1999;37(11):1140-1154. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. . Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100-e106. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. . A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105-1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linzer M, Poplau S, Brown R, et al. . Do work condition interventions affect quality and errors in primary care? results from the Healthy Work Place Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):56-61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3856-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linzer M, Gerrity M, Douglas JA, McMurray JE, Williams ES, Konrad TR. Physician stress: results from the Physician Worklife Study. Stress Health. 2002;18(1):37-42. doi: 10.1002/smi.917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez HR, Beyrouty M, Bennett K, et al. . Chaos in the clinic: characteristics and consequences of practices perceived as chaotic. J Healthc Qual. 2017;39(1):43-53. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75-79. doi: 10.1002/smi.1002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckleberry-Hunt J, Kirkpatrick H, Barbera T. The problems with burnout research. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):367-370. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwenk TL, Gold KJ. Physician burnout: a serious symptom, but of what? JAMA. 2018;320(11):1109-1110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. . Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014;3(4):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinsky CA, Beasley JW, Simmons GE, Baron RJ. Electronic health records: design, implementation, and policy for higher-value primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):727-728. doi: 10.7326/M13-2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA. Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: are we ignoring the real cause? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):50-51. doi: 10.7326/M18-0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fridsma DB. Comments to the ONC and CMS. American Medical Informatics Association. https://www.amia.org/sites/default/files/AMIA-Response-to-ONC-HIT-Burden-Reduction-Strategy.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2019.

- 28.Novacek P. Design displays for better pilot reaction. http://aea.net/AvionicsNews/ANArchives/DesignDisplayOct03.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2019.

- 29.Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. . Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):745-751. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.100255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gidwani R, Nguyen C, Kofoed A, et al. . Impact of scribes on physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and charting efficiency: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):427-433. doi: 10.1370/afm.2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milford J, Strasser MR, Sinsky CA. TEAM approach reduced wait time, improved “face” time. J Fam Pract. 2018;67(8):E1-E8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zahabi M, Kaber DB, Swangnetr M. Usability and safety in electronic medical records interface design: a review of recent literature and guideline formulation. Hum Factors. 2015;57(5):805-834. doi: 10.1177/0018720815576827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkureishi MA, Lee WW, Lyons M, et al. . Impact of electronic medical record use on the patient-doctor relationship and communication: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):548-560. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3582-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart RF, Kroth PJ, Schuyler M, Bailey R. Do electronic health records affect the patient-psychiatrist relationship? a before & after study of psychiatric outpatients. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenzel RP. RVU medicine, technology, and physician loneliness. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):305-307. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1810688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ergonomic considerations loom large as hospitals and other health care organizations rapidly adopt IT tools. ED Manag. 2013;25(3):31-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knox M, Willard-Grace R, Huang B, Grumbach K. Maslach Burnout Inventory and a self-defined, single-item burnout measure produce different clinician and staff burnout estimates. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1344-1351. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4507-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]