Abstract

This cohort study examines data from the WONDER database for all deaths attributed primarily to cerebrovascular disease between 2003 and 2017 to examine trends in location of death.

Advances in treatments have improved survival in patients with cerebrovascular disease, although little is known about the end-of-life experience of these patients.1 A critical patient-centric aspect of the end-of-life experience is location of death, with most patients preferring to die at home.2 However, the prevalence of locations of death and the factors determining location of death and hospice use in patients who died of stroke are unknown. We analyzed a national database to assess location of death for all patients who died from cerebrovascular disease in the United States from 2003 to 2017.

Methods

We used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database.3 Location of death categories for patients dying of cerebrovascular disease (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes I60-I69) included hospital, home, nursing facility, inpatient hospice facility, and other (outpatient medical facility, emergency department, and dead on arrival at the hospital). We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate associations between decedent characteristics and location of death for years in which we had individual level data from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2017. Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15.0 (Stata Corp), and data were analyzed between April 12, 2019, and April 24, 2019. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Duke University institutional review board owing to the use of deidentified and publicly available database data.

Results

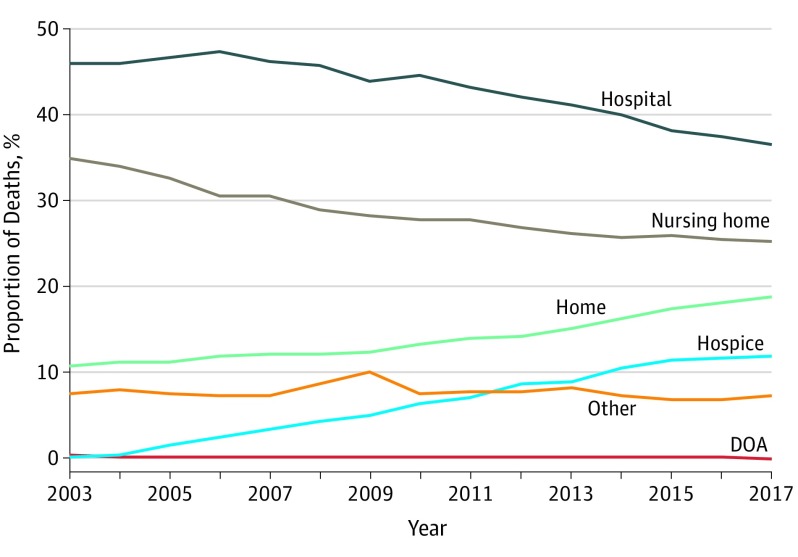

Between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2017, 2 065 286 deaths were attributed primarily to cerebrovascular disease, and during this period, deaths in hospitals and nursing facilities decreased and deaths at home and in hospice facilities increased (Figure). Cerebrovascular deaths occurring in the hospital decreased from 72 691 (46.1%) to 53 467 (36.5%) and nursing facility deaths fell from 55 156 (35.0%) to 37 127 (25.4%) while home deaths increased from 17 093 (10.8%) to 27 684 (18.9%) and hospice facility deaths increased from 271 (0.2%) to 17 364 (11.9%). Odds of hospital deaths decreased with age (odds ratio [OR] for patients aged 65-74 years, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.53-0.57] vs patients older than 85 years, 0.19 [95% CI, 0.18-0.21]) while odds of home deaths (OR for patients aged 65-74 years, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.26-1.41] vs patients older than 85 years, 2.21 [95% CI, 2.00-2.45]), in nursing facilities (OR for patients aged 65-74 years, 2.18 [95% CI, 2.13-2.23] vs patients older than 85 years, 4.69 [95% CI, 4.38-5.03]), and hospice facilities (OR for patients aged 65-74 years, 1.61 [95% CI, 1.57-1.66] vs patients older than 85 years, 1.86 [95% CI, 1.78-1.95]) increased with age (Table). Male decedents had greater odds of hospital death (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.06) and lower odds of home death (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99) relative to female decedents. Compared with white and non-Hispanic decedents, nonwhite and Hispanic decedents had reduced rates of death in a nursing facility (black decedents: OR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.78-0.81]; American Indian decedents: OR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.83-0.92]; Asian decedents: OR 0.63 [95% CI, 0.61-0.65]); Hispanic decedents: OR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.53-0.56]) or hospice facility (black decedents: OR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.89-1.00]; American Indian decedents: OR, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.54-0.69]; Asian decedents: OR 0.44 [95% CI, 0.42-0.46]); Hispanic decedents: OR, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.78-0.85]) and increased rates of death at home (black decedents: OR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.09-1.23]; American Indian decedents: OR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.00-1.33]; Asian decedents: OR 1.14 [95% CI, 1.09-1.20]); Hispanic decedents: OR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.39-1.48]) or in the hospital (black decedents: OR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.06-1.15]; American Indian decedents: OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.13-1.33]; Asian decedents: OR 1.66 [95% CI, 1.65-1.67]; Hispanic decedents, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.24-1.33]). Married decedents had increased odds of death in a hospital (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.32-1.36) or at home (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14-1.23) and reduced odds of death in a nursing facility (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.60-0.62) relative to nonmarried decedents. Decedents with some college had reduced odds of death in a nursing facility (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.98-1.02) and increased odds of death at home (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09) relative to decedents with less than high school education.

Figure. Trends in Location of Deaths for Individuals With Cerebrovascular Disease, 2003-2017.

DOA indicates dead on arrival at hospital.

Table. Association Between Decedent Characteristics and Location of Death, 2013-2017.

| Characteristc | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital vs All Other Locations of Death | Home vs All Other Locations of Death | Nursing Facility vs All Other Locations of Death | Hospice Facility vs All Other Locations of Death | |

| No. | 636 230 | 636 230 | 636 230 | 636 230 |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤64 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 65-74 | 0.55 (0.53-0.57)a | 1.33 (1.26-1.41)a | 2.18 (2.13-2.23)a | 1.61 (1.57-1.66)a |

| 75-84 | 0.35 (0.33-0.37)a | 1.74 (1.61-1.88)a | 3.17 (3.03-3.31)a | 1.87 (1.79-1.95)a |

| ≥85 | 0.19 (0.18-.21)a | 2.21 (2.00-2.45)a | 4.69 (4.38-5.03)a | 1.86 (1.78-1.95)a |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.05 (1.04-1.06)a | .98 (.97-.99)a | .991 (.979-1.00) | 1.02 (1.00-1.05) |

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 1.10 (1.06-1.15)a | 1.14 (1.06-1.23)b | 0.80 (0.78-0.81)a | 0.94 (0.89-1.00)c |

| American Indian | 1.23 (1.13-1.33)a | 1.15 (1.00-1.33) | 0.88 (0.83-0.92)a | 0.61 (0.54-0.69)a |

| Asian | 1.66 (1.65-1.67)a | 1.14 (1.09-1.20)a | 0.63 (0.61-0.65)a | 0.44 (0.42-0.46)a |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Hispanic | 1.29 (1.24-1.33)a | 1.44 (1.39-1.48)a | 0.55 (0.53-0.56)a | 0.81 (0.78-0.85)a |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Married | 1.34 (1.32-1.36)a | 1.19 (1.14-1.23)a | 0.61 (0.60-0.62)a | 1.02 (.989-1.05) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Some college or more | 1.00 (.98-1.02) | 1.07 (1.04-1.09)a | 0.90 (0.89-0.91)a | 1.02 (.99-1.05) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

P < .001.

P < .01.

P < .05.

Discussion

Our analysis provides novel insights into the end-of-life experience of patients who die from cerebrovascular disease. While the majority of patients had a stroke die in the hospital, our data suggest that the proportion of patients who had a stroke die at home, a location preferred by patients,2 has increased substantially. However, the experience of patients who had a stroke dying at home, and that of their caregivers, remains underinvestigated. Furthermore, we demonstrate that hospice facility use has also increased. The study’s primary limitations were reliance on death certificates alone for ascertaining location of death and inability to know whether hospice services were delivered for patients dying at home or in nursing facilities.

Finally, we noted important disparities. Patients who had a stroke who were nonwhite or Hispanic, while more likely to die at home or in a hospital, were less likely to die in a hospice facility than white and non-Hispanic patients. Lower use of palliative care and hospice services has been reported among minorities for other conditions and our analysis demonstrates consistency of this trend in stroke patients.4 Further research is needed to elucidate if racial and ethnic disparities in location of death represent a lack of access to home supports or hospice services or if they reflect differences in culture and care preferences.

References

- 1.Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Clinical Cardiology . Palliative and end-of-life care in stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(6):1887-1916. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov. Published 2017. Accessed April 14, 2019.

- 4.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329-1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]