Abstract

The widespread occurrence of natural and synthetic organic chemicals in surface waters can cause ecological risks and human health concerns. This study measured a suite of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in water samples collected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 8 around the Denver, Colorado, metropolitan area. The results showed that 109 of 144 analyzed pharmaceutical compounds, 42 of 55 analyzed waste-indicator compounds (e.g., flame retardants, hormones, and personal care products), and 39 of 72 analyzed pesticides were detected in the water samples collected monthly between April and November in both 2014 and 2015. Pharmaceutical compounds were most abundant in the surface waters and their median concentrations were measured up to a few hundred nanograms per liter. The CEC concentrations varied depending on sampling locations and seasons. The primary source of CECs was speculated to be wastewater effluent. The CEC concentrations were corre-lated to streamflow volume and showed significant seasonal effects. The CECs were less persistent during spring runoff season compared with baseflow season at most sampling sites. These results are useful for providing baseline data for surface CEC monitoring and assessing the environmental risks and potential human exposure to CECs.

Keywords: Contaminants of emerging concern, Pharmaceuticals, Personal care products, Flame retardants, Hormones, Pesticides

1. Introduction

The most critical challenges of urbanization are to supply fresh water to metropolitan areas and to dispose of wastewater without jeopardizing water resources and the environment. Most traditional water quality investigations have focused on nutrients, bacteria, heavy metals, and priority pollutants with known health effects such as pesticides, industrial chemicals, and petroleum hydrocarbons (Pal et al., 2014). In the past several decades, research has revealed the occurrence of hundreds of wastewater organic contaminants that could be a threat to the ecosystem after being released to surface waters. These contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) belong to diverse chemical classes and are typically detected at trace (i.e., ng/L or μg/L) levels in surface and subsurface waters. The high production and widespread use of synthetic chemicals for various purposes (e.g., pharmaceuticals and personal care products [PPCPs], illicit drugs, flame retardants, fragrances, plasticizers, and preservatives) result in their continuous release and ubiquitous distribution in the environment (Jobling et al., 1998; Focazio et al., 2008). The health effects of subtle, chronic human exposure to these contaminants include the development of anti-biotic resistance, endocrine disruption, and carcinogenicity (Cunningham et al., 2009; Brausch et al., 2012).

Many studies have reported the presence of CECs in surface waters worldwide (Stan and Heberer, 1997; Kolpin et al., 2002; Ternes et al., 2002; Lin and Reinhard, 2005; Ellis, 2006; Bu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). In the United States, a nationwide survey reported that 82 of the 95 wastewater organic contaminants that were analyzed were detected in 80% of the 139 streams sampled (Kolpin et al., 2002). Pharmaceutical compounds were detected in drinking water in Berlin, Germany (Stan and Heberer, 1997; Heberer, 2002), and 24 of the 28 major cities that were sampled in the United States (Loeb, 2008). Additionally, CECs have been widely monitored and found in groundwater in Italy (Meffe and de Bustamante, 2014), Africa (Sorensen et al., 2015), Spain (Jurado et al., 2012), and the United States (Fram and Belitz, 2011).

Rivers and water supply reservoirs in urban areas are typically used for drinking water and recreation activities, both of which are the most significant routes for human exposure. Sources of CECs in an urban watershed include households, hospitals, construction, landscaping, transportation, animal feeding, and municipal waste disposal (Pal et al., 2014). Water quality in an urban watershed is highly influenced by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) (Barber et al., 2013), which release wastewater effluents that contain complex mixtures of biologically active organic chemicals. Municipal WWTPs are not obligated to remove CECs, and therefore, except for the most biodegradable and/or hydrophobic compounds, treated wastewater inevitably contains a suite of CECs (Miao et al., 2002, 2004; Soulet et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2005; Lubliner et al., 2010) that becomes a significant concern once it is discharged into nearby surface water bodies. Most recently, Baalbaki et al. (2017) evaluated the removal of 23 CECs in two WWTPs and reported that the removal rate was >70% for all CECs using activated sludge treatment. Drug consumption patterns in large cities in Italy (Maida et al., 2017) and Spain (Mastroianni et al., 2017) have reported that alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine were the most consumed illicit and legal drugs, which may end up in the WWTPs and contaminate downstream waters.

Therefore, understanding the occurrence and distribution of complex organic contaminants helps predict and mitigate their potential effects on ecological and human health in aquatic envi-ronments. The study area—located in Denver, Colorado—has approximately three million residents and represents a typical urban watershed that is affected by municipal wastewater discharge, urban runoff across various land use types, and interactions with a river (i.e., the South Platte River) and its tributaries. Various aquatic species in the adjacent Colorado River and Mississippi River watersheds are documented as undergoing endocrine disruption (Bevans et al., 1996; Patino et al., 2003; Barber et al., 2015). This research will help find links between the presence of the organic contaminants and their health impacts in the downstream aquatic ecosystems. The objective is to determine the detection frequencies, concentrations, types, spatial and temporal distribution, and seasonality of pharmaceutical compounds, personal care products, flame retardants, pesticides, hormones, and other organic contaminants in this typical urban watershed that is affected by human activities. This information will be useful to provide data on CEC monitoring in surface water worldwide and help assess the potential exposure and risks.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

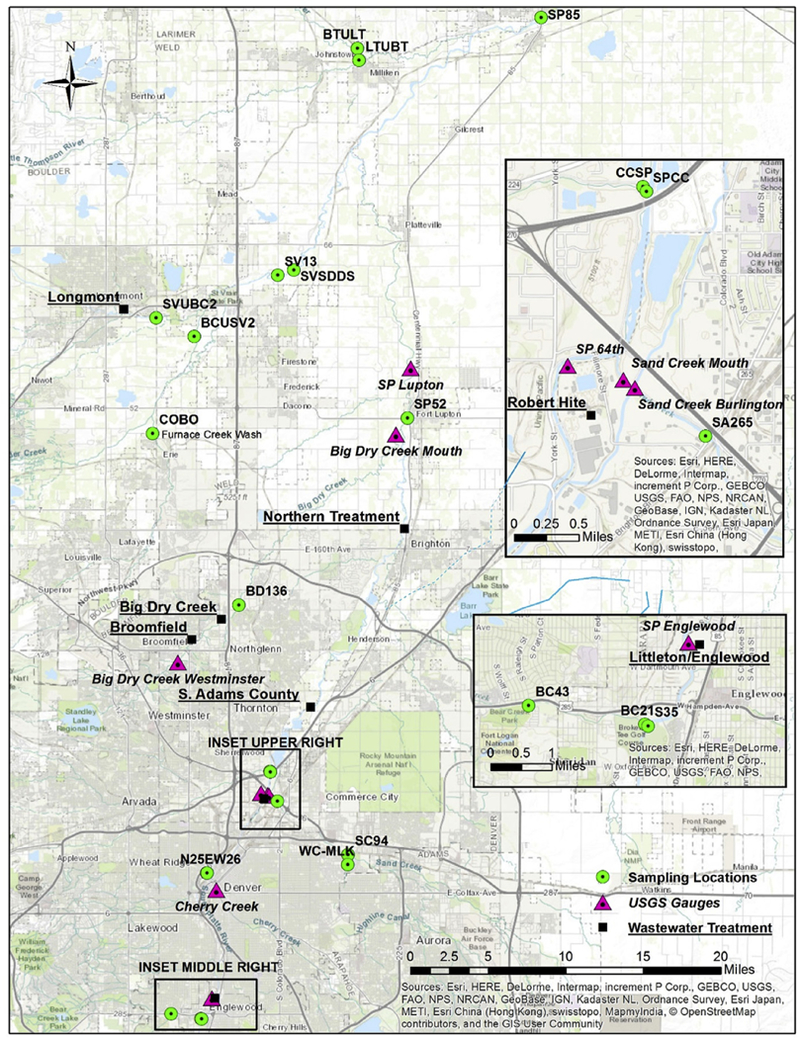

The study area is located in Denver, Colorado, and it is drained by the South Platte River and its tributaries, which are all sourced in the nearby Rocky Mountains. The river and tributaries experience fluctuation of flows throughout the year, but especially during spring melt conditions. To gain a better understanding of stream-flow and fluctuation, monthly averages of streamflow data were downloaded from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Information System (NWIS) Mapper (https://maps.waterdata.usgs.gov/mapper/index.html accessed in March, 2017). In this study, all NWIS data were used in their original format and no efforts were made to perform quality assurance beyond that of the reporting agency. Fig. 1 shows the map of the sampling sites, stream gauges, and adjacent WWTPs. Table S1 (Supporting Information) describes the 20 sampling sites, which represent various land cover types, such as residential, recreational, industrial, and commercial areas. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region 8 has collected water samples at these locations along the South Platte River and its tributaries as they flow through the metropolitan area.

Fig. 1.

Map of sampling sites, nearby USGS gauges, and wastewater treatment facilities at the study sites in Denver, Colorado.

The study area is highly influenced by snowmelt during the spring season, so streamflow was evaluated based on spring runoff (May, June, and July) and baseflow (the other months of the year). Table S2 (Supporting Information) summarizes the USGS gauges in the Denver area that are in proximity of the EPA sampling locations. Spring runoff and baseflow are listed in separate columns to show the variation of streamflow between the different seasons. The WWTPs in the metropolitan area, which are considered primary point sources of contaminants in downstream waters, are also mapped in Fig. 1 and summarized in Table S3 (Supporting Information).

2.2. Water sample collection

Water samples were collected by the EPA Region 8 at each site monthly from April to November in both 2014 and 2015. For the majority of sampling, grab samples were taken, and several composite samples were only collected at 4 selected sites over 5 days in September, 2014. The purpose of this monitoring effort was to provide information on the occurrence and frequency of CECs throughout the Denver surface water by collecting grab samples at the same monitoring locations over time. In spite of the limitations of grab samples, the consistent and frequent sampling at locations within this urban watershed provides relevant information on the occurrence, frequency, and levels of CECs during the times of collection at these sites. Several field blanks and duplicates were taken for quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC). Water samples for waste-indicator compound analysis were collected in either 250 mL or 1 L amber glass bottles. Water samples for pesticide and PPCP analysis were collected in sterile 40 mL amber glass Volatile Organic Analysis (VOA) vials. Samples were immediately transported on ice to the laboratory and stored at 4 °C until further analysis. A total of 144 and 167 samples were collected and analyzed for 2014 and 2015, respectively.

2.3. Chemical analysis

Chemical analysis followed the EPA Region 8 Laboratory Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for PPCPs, pesticides and herbi-cides, and waste-indicator compounds. Detailed information on the analytical methods and QA/QC can be found in the Supporting Information.

Method 1:

Following the EPA Region 8 Laboratory SOP for PPCPs (i.e., EPA Method 1694), 144 pharmaceutical compounds were analyzed in water using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The EPA Method 1694 includes the detection of a broad class of PPCPs by direct injection in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode LC-MS/MS. Briefly, 3 mL of water sample was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane filter (Whatman®, Piscataway, NJ), 25 μL of internal standard was added to a 1 mL aliquot of the filtered sample, and 50 μL of the sample was injected directly to UHPLC. The UHPLC-MS/MS used was Agilent 1290/6460 series (Palo Alto, CA), and the column used was Acquity BEH C18 (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) for ES1+ and Restek Ultra II Aromax (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.9 μm particle size) for ESI-.

Method 2:

Following the EPA Region 8 Laboratory technical SOP, 72 pesticides and herbicides were measured using direct aqueous injection in UHPLC-MS/MS. The method is similar to the PPCP analysis (Method 1) except for different UHPLC liquid conditions (see Supporting Information).

Method 3:

After passing through liquid-liquid extraction with methylene chloride, 55 waste-indicator compounds were measured in the water samples using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS, HP 6890 and HP 5975 MSD equipped with a triple axis detector and a 30 mm × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness silicone-coated, fused-silica capillary column). The waste-indicator compounds in this study only represent the compounds that were analyzed using Method 3, but not defined by scientific meanings.

2.4. Data analysis

All analytes with at least one detection above the method reporting limit (MRL) were presented and statistically analyzed. The significance between data was determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Student’s t-test was used to determine whether there were significant differences between levels. The results were statistically significant when p values were less than 0.05 (95% confidence interval). The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the seasonality of CECs with respect to streamflow. The values of correlation and the corresponding strength of correlation were interpreted as: ≥ 0.6 strong; 0.4–0.6 moderate; < 0.4 weak (Helsel and Hirsch, 2002). All statistical analysis was done using Minitab (version 17.0, Minitab, Inc.) and JMP (version 13.0, SAS 1nstitute, 1nc.).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Occurrence and persistence of CECs

3.1.1. Pharmaceuticals

Of all the 109 detected pharmaceutical compounds, Table 1 summarizes the top 30 most frequently detected compounds and their typical use, median and maximum concentration, frequency of detection, and ecotoxic index (i.e., lethal concentration [LC50]) based on fish species, as reported by the U.S. EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase (https://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/ accessed in March 2017). The detection frequencies of the 30 compounds ranged from 43.8% to 100% in the two years of sampling. These 30 compounds represent a wide variety of drug classes and origins. Anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensives, and beta-blockers are the classes that are found most often, which is likely because of their high water solubility and low metabolic rates in human body, wastewater treatment processes, and the natural environment.

Table 1.

Summary of the selected analytes that were most frequently detected in water samples collected in 2014 and 2015 in the Denver area; n = number of samples; MRL = method reporting limit (ng/L); Med = median concentration (ng/L); Max = maximum concentration (ng/L); LC50 = lowest 50% lethal concentration (μg/L) on indicator fish species (U.S. ECOTOX Knowledgebase); ND = not detected; NA = not applicable; d = day.

| Pesticides (Method 1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 (n = 144) | 2015 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| Analyte | Typical use | CAS | MRL | Med | Max | Frequency | Med | Max | Frequency | LC50 |

| Atenolol | Beta blocker | 29122-68-7 | 10 | 104 | 1850 | 77.1% | 46.8 | 1150 | 73.7% | 755000a |

| Caffeine | Stimulant | 58-08-2 | 25 | 111 | 3760 | 71.5% | 68.2 | 1390 | 57.5% | 40000b |

| Carbamazepine | Anticonvulsant | 298-46-4 | 10 | 40.1 | 390 | 77.8% | 38.5 | 229 | 77.2% | 16800b |

| Cotinine | Nicotine metabolite | 486-56-6 | 10 | 22.5 | 639 | 61.1% | 18.1 | 120 | 59.3% | NA |

| DEET | Insect repellent | 134-62-3 | 10 | 56.8 | 639 | 91.7% | 59.4 | 3970 | 92.8% | 110000b |

| Desmethyl-venlafaxine | Antidepressant | 93413-62-8 | 10 | 159 | 1100 | 87.5% | 148 | 1280 | 83.8% | NA |

| Diclofenac | Anti-inflammatory | 15307-86-5 | 10 | 50.3 | 444 | 45.1% | 26.1 | 4830 | 40.1% | 70980c |

| Gabapentin | Antiepileptic | 60142-96-3 | 10 | 682 | 11 200 | 97.9% | 440 | 4730 | 99.4% | 8550000d |

| Gemfibrozil | Antihyperlipidemic | 25812-30-0 | 10 | 50.9 | 677 | 49.3% | 32.3 | 409 | 42.5% | 851d |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Antihypertensive | 58-93-5 | 10 | 112 | 819 | 77.8% | 112 | 1470 | 82.6% | 29774e |

| Hydroxybupropion | Antidepressant | 92264-81-8 | 10 | 79.8 | 526 | 83.3% | 67 | 549 | 80.8% | NA |

| Hydroxycarbamazepine | Anticonvulsant | 29331-92-8 | 10 | 91.6 | 652 | 86.1% | 132 | 993 | 79.6% | NA |

| Lamotrigine | Antiepileptic | 84057-84-1 | 10 | 258 | 2390 | 93.8% | 318 | 2200 | 93.4% | NA |

| Levorphanol | Pain reliever | 77-07-6 | 10 | 76.2 | 668 | 70.1% | 41.3 | 269 | 54.5% | NA |

| Lidocaine | Antiarrhythmic | 137-58-6 | 10 | 52.1 | 395 | 74.3% | 58.9 | 382 | 73.1% | NA |

| Meprobamate | Antianxiety | 57-53-4 | 10 | 43.8 | 202 | 70.1% | 36.1 | 203 | 68.9% | NA |

| Metformin | Antidiabetic | 657-24-9 | 10 | 343 | 5450 | 95.1% | 366 | 7130 | 100.0% | NA |

| Metoprolol | Beta blocker | 37350-58-6 | 10 | 57.2 | 499 | 68.1% | 42.4 | 336 | 67.1% | NA |

| Oxcarbazepine | Anticonvulsant | 28721-07-5 | 10 | 34.2 | 267 | 45.8% | 32.5 | 273 | 55.7% | NA |

| Oxycodone | Pain reliever | 76-42-6 | 10 | 29.5 | 126 | 54.2% | 26.6 | 113 | 53.3% | NA |

| Phenytoin | Antiepileptic | 57-41-0 | 10 | 27.5 | 145 | 51.4% | 22.2 | 130 | 45.5% | 63075d |

| Pregabalin | Antiepileptic | 148553-50-8 | 10 | 42.0 | 252 | 58.3% | 42.2 | 196 | 53.3% | NA |

| Sotalol | Beta blocker | 959-24-0 | 10 | 32.8 | 111 | 59.7% | 27.8 | 122 | 58.7% | NA |

| Sulfamethoxazole | Antibiotic | 723-46-6 | 10 | 119 | 727 | 87.5% | 90 | 772 | 87.4% | 562500a |

| Temazepam | Antianxiety | 846-50-4 | 10 | 24.4 | 212 | 56.3% | 29.5 | 231 | 42.5% | NA |

| Tramadol | Pain reliever | 27203-92-5 | 10 | 91.1 | 854 | 84.0% | 81 | 635 | 86.2% | NA |

| Triamterene | Antihypertensive | 396-01-0 | 10 | 35.5 | 1440 | 52.1% | 26.6 | 1880 | 50.9% | NA |

| Trimethoprim | Antibiotic | 738-70-5 | 10 | 40.8 | 633 | 68.8% | 32.9 | 274 | 60.5% | 3000f |

| Valsartan | Antihypertensive | 137862-53-4 | 10 | 46.7 | 483 | 43.8% | 23 | 292 | 50.3% | NA |

| Venlafaxine | Antidepressant | 93413-44-6 | 10 | 59.4 | 481 | 75.0% | 51.1 | 434 | 74.3% | NA |

| Waste Indicator Compounds (Method 3) | ||||||||||

| 2014 (n = 144) | 2015 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| Analyte | Typical use | CAS | MRL | Med | Max | Frequency | Med | Max | Frequency | LC50 |

| 1,4-Dichlorobenzene | Disinfectant | 106-46-7 | 50 | 192 | 327 | 8.3% | 104 | 151 | 4.2% | 1100c |

| Acetophenone | Precursor | 98-86-2 | 50 | 81.0 | 520 | 25.7% | 89.8 | 187 | 13.8% | 155000b |

| Benzophenone | UV blocker | 119-61-9 | 50 | 91.9 | 574 | 21.5% | 83.5 | 288 | 16.2% | 10890b |

| Bisphenol A | Plastic | 80-05-7 | 50 | 150 | 923 | 31.3% | 139 | 705 | 50.9% | 3600b |

| Butylated hydroxyanisole | Food additive | 25013-16-5 | 100 | ND | ND | 0.0% | 475 | 482 | 44.9% | 1000f |

| Galaxolide | Musk | 1222-05-5 | 50 | 275 | 3300 | 65.3% | 270 | 2720 | 70.1% | NA |

| Phenol | Precursor to plastic | 108-95-2 | 50 | ND | ND | 0.0% | 90.8 | 542 | 33.5% | 4000c |

| Tonalide | Musk | 21145-77-7 | 50 | 125 | 201 | 6.9% | 84.9 | 198 | 19.2% | NA |

| Tri (2-butoxyethyl) Phosphate | Flame retardant | 78-51-3 | 50 | 564 | 6880 | 61.8% | 978 | 10100 | 71.9% | NA |

| Tri (2-chloroethyl) Phosphate | Flame retardant | 115-96-8 | 50 | 113 | 450 | 50.0% | 113 | 274 | 50.9% | NA |

| Tri (dichloroisopropyl) Phosphate | Flame retardant | 13674-87-8 | 50 | 216 | 956 | 88.2% | 162 | 773 | 75.4% | NA |

| Tributyl phosphate | Plasticizer | 126-73-8 | 50 | 178 | 1730 | 23.6% | 109 | 602 | 13.8% | 4200f |

| Triclosan | Antibacterial | 3380-34-5 | 50 | 165 | 872 | 18.8% | 92.4 | 430 | 11.4% | 180b |

| Triethyl citrate | Food additive | 77-93-0 | 50 | 194 | 1620 | 51.4% | 185 | 1800 | 55.7% | NA |

| Triphenyl phosphate | Flame retardant | 115-86-6 | 50 | 73.7 | 160 | 22.2% | 66.2 | 120 | 13.2% | 280c |

| Hormones (Method 3) | ||||||||||

| 2014 (n = 144) | 2015 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| Analyte | Typical use | CAS | MRL | Med | Max | Frequency | Med | Max | Frequency | LC50 |

| 17β-Estradiol | Estrogen | 50-28-2 | 100 | 612 | 1960 | 5.6% | 393 | 1670 | 11.4% | 0.002a |

| Estrone | Estrogen | 53-16-7 | 100 | 164 | 165 | 0.7% | 112 | 124 | 1.2% | NA |

| 17α-Ethinylestradiol | Birth control | 57-63-6 | 100 | 431 | 431 | 0.7% | 228 | 358 | 9.6% | 0.1g |

| Pesticides (Method 2) | ||||||||||

| 2014 (n = 144) | 2015 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| Analyte | Typical use | CAS | MRL | Med | Max | Frequency | Med | Max | Frequency | LC50 |

| 2,4-D | Herbicide | 94-75-7 | 10 | 114 | 3790 | 97.9% | 73.8 | 2730 | 97.6% | 5100c |

| Atrazine | Herbicide | 1912-24-9 | 10 | 28.2 | 1250 | 41.0% | 14.7 | 70.3 | 40.1% | 15000b |

| Bromacil | Herbicide | 314-40-9 | 50 | 80.8 | 1190 | 13.2% | 74.7 | 257 | 10.8% | 185000b |

| Carbaryl | Insecticide | 63-25-2 | 10 | 19.2 | 154 | 11.1% | 30.1 | 221 | 9.0% | 5210b |

| Diuron | Herbicide | 330-54-1 | 20 | 52.4 | 1310 | 52.1% | 40.6 | 581 | 45.5% | 14200b |

| Pesticides (Method 1) | ||||||||||

| 2014 (n = 144) | 2015 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| Analyte | Typical use | CAS | MRL | Med | Max | Frequency | Med | Max | Frequency | LC50 |

| Imidacloprid | Insecticide | 138261-41-3 | 20 | 40.1 | 339 | 27.1% | 30.2 | 298 | 12.6% | 194000d |

| MCPP | Herbicide | 7085-19-0 | 20 | 58.6 | 976 | 58.3% | 53.6 | 789 | 51.5% | 10000f |

| Metolachlor | Herbicide | 51218-45-2 | 10 | 17.3 | 778 | 25.7% | 22 | 233 | 21.6% | 8400b |

| Metolachlor ESA | Herbicide | 947601-85-6 | 20 | 90.0 | 1040 | 37.5% | 113 | 742 | 40.1% | NA |

| Triclopyr | Herbicide | 55335-06-3 | 20 | 47.4 | 5210 | 25.0% | 38.2 | 330 | 16.8% | 7500h |

Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) – 4 day exposure.

Fathead minnow (Pimephalespromelas) – 2 d exposure.

Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) – 4 d exposure.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) – 4 d exposure.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) – 5 d exposure, LC25.

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) – 5 d exposure.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) – 28 d exposure.

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) – 4 d exposure.

The highest median concentration of pharmaceutical compounds was measured for gabapentin (559.5 ng/L), and then met-formin (356.0 ng/L), lamotrigine (305.5 ng/L), desmethylvenlafaxine (152.0 ng/L), hydrochlorothiazide (112.0 ng/ L), sulfamethoxazole (104.0 ng/L), and hydroxycarbamazepine (103.0 ng/L). The antiepileptic gabapentin had the highest detection frequencies and concentrations of all of the pharmaceuticals analyzed. However, according to toxicological tests on fish, gaba-pentin has a high LC50 (i.e., 8550 mg/L), indicating that it may not be a significant concern to aquatic species despite its high levels in surface waters. Compounds measured at concentrations that are a few orders of magnitude lower than the reported LC50 may not be a threat to aquatic wildlife, especially for short-term exposure. Chronic, subtle exposure may still cause adverse effects to aquatic organisms, but so far this is unclear. Of the highly detected pharmaceutical compounds, gemfibrozil and trimethoprim are relatively more toxic compared with the other analytes summarized in Table 1 due to their low LC50, and therefore understanding their fate and transport is of greater concern. To fully evaluate the health risks associated with CECs in surface waters, each compound needs to be tested on various aquatic organisms to determine its ecotoxic effects. However, the lack of ecotoxic data for some compounds hinders understanding their potential ecological risks. The effects of mixed pharmaceutical compounds differ from the effects of individual compounds. Therefore, using the individual compound data may result in underestimating the ecological risks, which is one of the biggest challenges in environmental risk assessment.

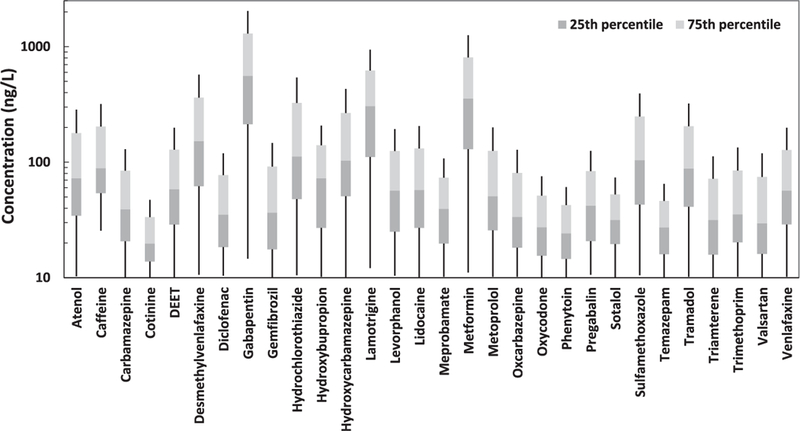

Fig. 2 shows box plots of the concentration distribution for the 30 pharmaceutical compounds. The concentrations ranged between the MRL (i.e., 10 or 25 ng/L) to several thousand nanograms per liter. These contaminants have also been reported at high levels and frequencies of detection in other surface and subsurface waters worldwide. For example, the stream survey conducted by Kolpin et al. (2002) in the United States reported that the median con-centration for sulfamethoxazole, metformin, gemfibrozil, and trimethoprim was 66 ng/L (detection frequency = 19%), 110 ng/L (detection frequency = 4.8%), 48 ng/L (detection frequency = 3.6%), and 150 ng/L (detection frequency = 12.5%), respectively. Boyd and Furlong (2002) monitored selected pharmaceuticals in Lake Mead and the Las Vegas Wash—which are located in southern Nevada-—and found that carbamazepine ranged from 2 to 140 ng/L, sulfa-methoxazole ranged from 30 to 200 ng/L, and trimethoprim ranged from 15 to 98 ng/L. A more recent study (Wilson and Jones-Lepp, 2013)measured CECs in groundwater from the Colorado River Mile 221 and Thompson Bay/Lake Havasu monitoring wells near Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and found that carbamazepine averaged 4.0 and 3.1 ng/L, gemfibrozil averaged 0.52 and 0.41 ng/L, trimeth-oprim averaged 0.4 and 0.4 ng/L, sulfamethoxazole averaged 12.5 and 9.5 ng/L, and meprobamate average10.9 and 10.7 ng/L, respectively. The Southern Nevada Water Authority (2015) moni-tored selected pharmaceuticals in Lake Mead, Nevada, and the median concentration was 14, 6.3, 3.2, and 3.1 ng/L for sulfameth-oxazole, meprobamate, carbamazepine, and primidone, respectively. The authors previously monitored selected PPCPs in a wetland (i.e., Las Vegas Wash) downstream of four major WWTPs in the Las Vegas Valley and found that sulfamethoxazole and car-bamazepine were 360 and 110 ng/L, respectively (Bai and Acharya, 2017). The results of this study further documented the ubiquitous occurrence of various pharmaceutical compounds in surface water systems in urban areas, which can be useful data for predicting their fate, transport, and ecological risks.

Fig. 2.

Measured concentrations of top 30 most frequently detected pharmaceutical compounds. Box plots show concentration distribution at the reporting level.

This study found that metabolites of commonly prescribed pharmaceutical drugs were also among the most frequently detected analytes. The frequent detection of hydrox-ycarbamazepine (metabolite of carbamazepine), cotinine (metab-olite of nicotine), desmethylvenlafaxine (metabolite of venlafaxine), hydrochlorothiazide (metabolite of thiazide), and hydroxybupropion (metabolite of bupropion) demonstrated the occurrence of CEC metabolites in the hydrologic system. Therefore, the predominant metabolites should be monitored (Kolpin et al., 2002) to accurately assess their fate, transport, and adverse effects on human and environmental health (such as pathogen resistance), especially considering that most metabolites are usually more hydrophilic and mobile in aquatic environments than their parent compounds.

3.1.2. Waste-indicator compounds and hormones

A group of waste-indicator compounds—including flame re-tardants, musks, hormones, UV blockers, and plasticizers—was also analyzed in all of the samples. Table 1 summarizes the top 15 most frequently detected indicator compounds of the 42 compounds analyzed. Of all the waste-indicator compounds in the sampled watershed, the flame retardants tri (2-butoxyethyl) phosphate, tri (2-chloroethyl) phosphate, and tri (dichloroisopropyl) phosphate were found at the highest concentrations and frequencies. Unlike pharmaceutical compounds, flame retardants and personal care products are applied externally and do not undergo any metabolic changes prior to their release to the aquatic environment (Pal et al.,2014). However, because of their extensive daily use, they are widely observed in surface waters and have the potential of bio-accumulation in aquatic species (Brausch and Rand, 2011 ). Flame retardants are widely used in thermostats, textiles, furniture and electronics coatings, and thermoplastics and they are widespread in the environment. Tri (2-chloroethyl) phosphate was reported from 900 to 1000 ng/L in secondary wastewater effluents and from 900 to 1400 ng/L in tertiary wastewater effluents (Lubliner et al.,2010). In surface waters, tri (2-chloroethyl) phosphate and tri (dichloroisopropyl) phosphate were both reported at a median concentration of 100 ng/L with detection frequencies of 57.6% and 12.9% in the 139 sampled streams (Kolpin et al., 2002). Additionally, flame retardants are easily accumulated in biomass and documented to be present in human and animal tissues, blood, and milk because of their high hydrophobicity (Houtman, 2010; Ela et al.,2011).

Triclosan is one of the most commonly found personal care products in the environment that has the lowest LC50 value compared with other waste indicators (Table 1). Triclosan is an antimicrobial that is widely used in toothpaste, soap, and deodorant, which was measured at levels of up to 805 and 77 ng/L in secondary and tertiary wastewater effluent, respectively (Lubliner et al., 2010). In the Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi River regions, triclosan was reported ranging from <100 to 1400 ng/ L in wastewater effluent samples (Barber et al., 2015). Triclosan was detected in 57.6% of the 139 sampled streams in the United States at a median concentration of 140 ng/L (Kolpin et al., 2002). Triclosan was also measured at 8.0 ng/L in the Las Vegas Wash (Bai and Acharya, 2017). Triclosan can be rapidly taken up by freshwater algal species (Bai and Acharya, 2016, 2017) and the bio-accumulation factor is reported at 900—2100 in alga Cladophora spp. (Coogan et al., 2007), indicating its high bioaccumulation and biomagnification potentials within the food web.

Although hormones were found at much lower frequencies compared with other CECs because of the high method detection limits (i.e., 50 ng/L), they are also listed in Table 1 because of their significant health effects at extremely low levels. Estrogenic hor-mones can cause adverse effects on fish at levels as low as a few nanograms per liter, and the reported LC50 values of estrogens are 2–100 ng/L (Table 1), which are several orders of magnitude lower than other CECs listed. Naturally occurring hormones are currently known to be the most potent endocrine disrupting chemicals, and their persistence in the environment is of great concern. The detection frequencies of estrogenic hormones ranged from 7.1% to 15.7% in U.S. streams, and the median concentrations were 9–160 ng/L(Kolpin et al., 2002). The current results showed higher concentrations but lower detection frequencies of hormones compared with the previous national stream survey (Kolpin et al., 2002), which suggests that more sophisticated sampling regimes and sensitive analytical methods—such as using passive samplers for hydrophobic compounds (Rosen et al., 2010)—may be necessary to accurately monitor hormones in surface waters. Additionally, this study did not attempt to measure conjugated estrogens, which can be a precursor to the release of free estrogens in the environment (Shrestha et al., 2012; Bai et al., 2013, 2015). In future studies, conjugated estrogens should be monitored because they are more mobile in water and more resistant to biodegradation compared with free estrogens.

3.1.3. Pesticides

The widespread use of pesticides in agriculture, landscaping, horticulture, golf courses, and other amenities results in the transport of pesticides from the land surface to surface water and groundwater via runoff and percolation (Pal et al., 2014). This study found 39 pesticides with at least one detection. Table 1 lists the top 10 most frequently detected pesticides. The pesticide 2,4-D was the most abundant in the watershed, with a nearly 98% detection frequency at median concentrations of 114 ng/L and 73.8 ng/L in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Overall, pesticides were less abundant than pharmaceuticals and other organic contaminants found in the water samples.

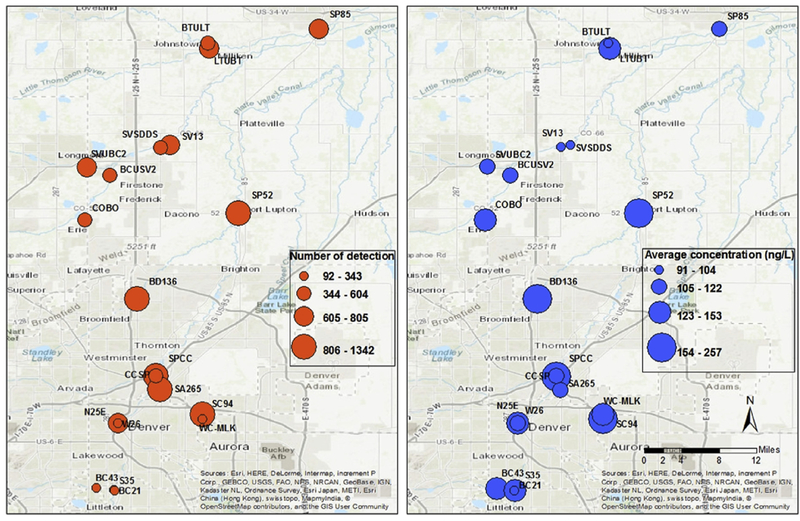

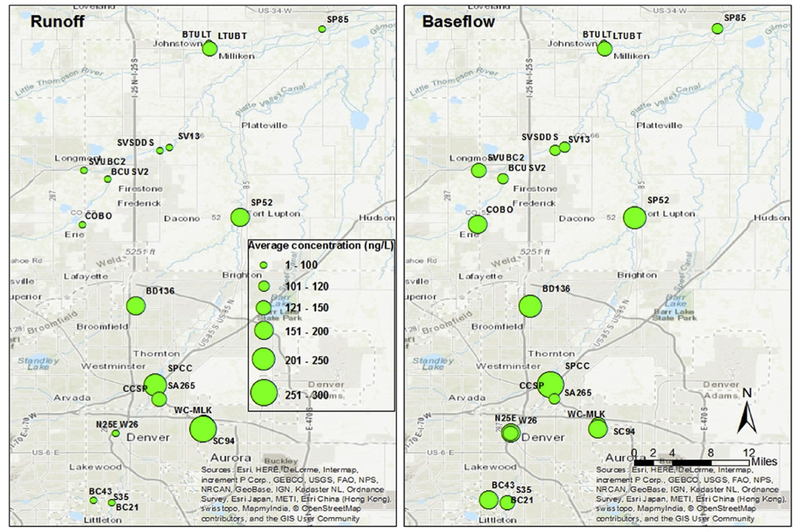

3.2. Spatial variation of CECs

The 20 sampling sites in the watershed represent various land use and land cover types, as well as population density. The results showed that the CEC concentrations varied significantly depending on sampling locations (p < 0.0001). Fig. 3 shows the number of detections and concentrations of CECs. The sampling sites with both the highest CEC detections and concentrations are the South Platte River and Clear Creek Confluence (SPCC), Big Dry Creek (BD136), South Platte 52 (SP52), and the Sand Creek and Westerly Creek Confluence (SC94). The maps show that the highly contam-inated areas are the central (along the South Platte River) and southeastern (along the Sand Creek) metropolitan areas. Anthropogenic-derived contaminants can increase in surface water as the population density increases (Barber et al., 2006). More sampling sites should be selected along the South Platte River and the Sand Creek to obtain a better understanding of the CEC distribution.

Fig. 3.

Map of the number of detection and average concentration of all analytes in the sampled area during both 2014 and 2015.

Site SPCC recorded the highest CEC concentrations and detection and it is downstream of the Robert Hite Treatment Facility, which is the largest wastewater treatment facility in the entire Denver metropolitan area (Fig. 1 ). The facility treats approximately 130 million gallons of wastewater each day from 1.8 million people in the Denver area and upon discharge, the treated wastewater can make up 85% of the South Platte River flow (Metro Wastewater Reclamation District http://www.metrowastewater.com). Site BD136 receives treated wastewater from the Westminster’s Big Dry Creek Wastewater Treatment Facility, which has the capacity to treat up to 12 million gallons a day. Numerous untreated contaminants are released into the watershed via wastewater discharge, which most likely includes pharmaceuticals, personal care products, flame retardants, and hormones. Therefore, wastewater effluent is considered the largest CECs input in this area. Water quality downstream of WWTPs is determined by dilution with upstream water, hydraulic residence times, and in-stream attenu-ation processes (Barber et al., 2013). All of those parameters need to be monitored to fully understand the transport of CECs from WWTPs to downstream waterbodies.

Sites SP52 and SC94 are not located immediately downstream of a WWTP, and therefore the sources of CECs at these two locations may be more complex. Site SP52 is the farthest downstream on the South Platte River that receives runoff from the Denver metropolitan area and may be most representative of the complex urban setting, which is affected by various land cover types. It is presumed that the large areas of agricultural lands surrounding SP52 bring pesticides and herbicides to the watershed via surface runoff. Site SC94 is located at the confluence of the tributaries Sand Creek and Westerly Creek, where upstream recreation parks, forests, and golf courses maybe the primary sources of CECs. Interestingly, site SA265 (Sand Creek d/s of Hwy 265-Brighton Blvd) shows lower CECs compared with its upstream counterpart SC94, which suggests CEC attenuation as the Sand Creek flows through. The farthest downstream site along the South Platte River—SP85 (South Platte River at US Hwy 85 in Greeley)—receives inflow from St. Vrain and Boulder Creeks, as well as numerous tributaries around and above the community of Loveland and had lower CECs levels than the upstream sites. The natural attenuation of CECs from upstream to downstream (i.e., sites SP52 to SP85 and SC94 to SA265) may be attributed to biotic and abiotic transformations, bioaccumulation, and photodegradation caused by intense solar radiation as the CECs travel along the river.

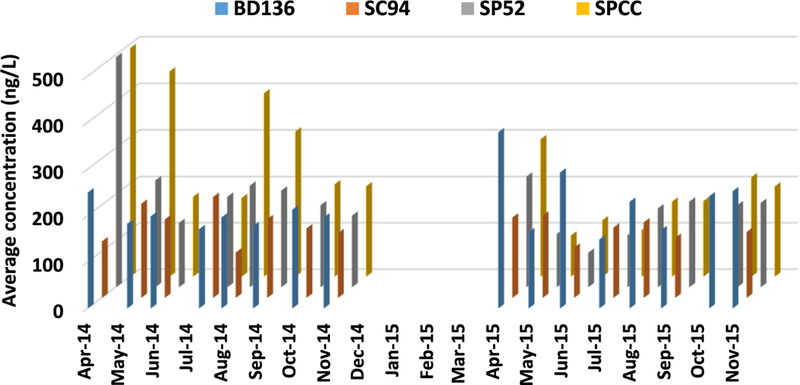

3.3. Seasonal effects on CEC concentrations

Fig. 4 shows a time series of average CEC concentrations in the four most contaminated sites: SPCC, BD136, SP52, and SC94. A visually discernible trend shows that the CEC concentrations varied depending on sampling time, especially for sites SPCC and SP52. The lowest CEC concentrations occurred during the largest streamflow increases in May, June, and July. The study area is highly influenced by snowmelt during spring, and therefore the seasonal effects are evaluated based on spring runoff (May, June, and July) versus baseflow (other months) seasons. The CEC concentrations showed significant seasonal effects (p = 0.018). Fig. 5 shows the CEC concentrations during spring runoff versus baseflow seasons, from which CECs were at much higher concentrations in the baseflow season compared with the spring runoff season for most sampling sites. Furthermore, the sites with the most apparent CEC reduction during spring runoff are the tributaries far away from the central metropolitan area, which receive snowmelt runoff (e.g., COBO, SVSDDS, and BCUSV2 in Fig. 5). In the spring and early summer, increased streamflow of the Colorado River from snowmelt could contribute to the dilution and attenuation of the contaminants, and other factors such as algal blooms may help remove the contami-nants in the surface water via promoted bioaccumulation and photodegradation (Bai and Acharya, 2016, 2017). A previous study also documented that the maximum contaminant load occurs during the baseflow season in the Boulder Creek watershed in the Colorado Front Range, which receives snowmelt runoff from the Rocky Mountains (Barber et al., 2006). Additionally, using a more sophisticated sampling method is recommended in future studies. Grab samples only represent an instantaneous measurement and a snapshot of conditions at a specific location and time. Therefore, grab samples may not capture analytes and concentrations that are highly variable over time. Increasing the frequency of sampling can ameliorate some of these limitations and provide useful information on the spatial and temporal variation of the contaminants.

Fig. 4.

Time series of average CEC concentrations in the top four most contaminated sites (BD136, SC94, SP52, and SPCC).

Fig. 5.

Map of the seasonal effects on CEC concentrations during the spring runoff (May, June, and July) and baseflow (other months) seasons.

The correlation between CEC concentrations and streamflow volume measured at the nearby gauges was determined for the four most contaminated sites (Table S4; Supporting Information). The results showed weak to moderate correlation (i.e., ≥0.6 strong; 0.4–0.6 moderate; < 0.4 weak) for all sites, and all correlation co-efficients were negative except for site SC94. The negative correlation indicates that CEC concentration decreases as streamflow increases, and vice versa. The positive correlation indicates that CEC concentration increases as streamflow increases and CEC decreases as streamflow decreases. The different relationship at SC94 suggests that CECs at this site may originate from varied sources compared with the other sites. As discussed earlier, site SC94 is affected by the adjacent land cover types, including golf course, dog parks, and recreation parks and surface runoff is likely the major source of CECs. Therefore, increased streamflow during the spring runoff season likely introduces more CECs from the land surface to surface waters, which results in higher CEC concentrations.

4. Conclusions

This study measured complex organic contaminants in the water samples collected from the Denver urban area in Colorado. The goal was to gain knowledge on the occurrence of CECs in surface waters to better understand and mitigate the potential environmental risks. There were numerous CECs detected in this urban watershed and the median concentrations measured up to several hundred nanograms per liter depending on the drug class, chemical type, sampling season, and location. Pharmaceutical compounds, personal care products, flame retardants, and pesticides were widely distributed in the sampled areas. Combined with their toxicological index, the ecological risks associated with these CECs can be evaluated using the monitoring data, and significant attention should be given to the high toxic compounds with frequent detection. The spatial variation of the detected CECs suggests that municipal wastewater discharge is the primary CEC source and that CEC distribution may also be affected by land cover types and surface runoff. The most contaminated areas are located in the central and southeastern metropolitan areas along the South Platter River and Sand Creek. The CEC concentrations and distri-butions also showed significant seasonality between spring runoff and baseflow seasons. At most sampling sites, spring runoff would facilitate the removal of CECs, and CECs were more persistent in the surface waters during the entire baseflow season of the year. The results demonstrate that CECs are ubiquitous in aquatic environ-ments and the long-term health effects and ecological risks need to be further evaluated.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Emerging contaminants were monitored in an urban watershed for two years.

109 of 144 analyzed pharmaceutical compounds were detected.

42 of 55 analyzed waste-indicator compounds were detected.

39 of 72 analyzed pesticides were detected.

Emerging contaminants showed clear spatial variability and seasonality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the U.S. EPA Region 8 Laboratory, especially to Karl Hermann. This study was funded by the Desert Research Institute under an Institute Project Assignment grant.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.106.

References

- Baalbaki Z, Sultana T, Metcalfe C, Yargeau V, 2017. Estimating removals of contaminants of emerging concern from wastewater treatment plants: the critical role of wastewater hydrodynamics. Chemosphere 178, 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Acharya K, 2016. Removal of trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, and triclosan by thegreen alga Nannochloris sp. J. Hazard Mater. 315, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Casey FX, Hakk H, DeSutter TM, Oduor PG, Khan E, 2015. Sorption and degradation of 17beta-estradiol-17-sulfate in sterilized soil-water systems. Chemosphere 119, 1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Casey FXM, Hakk H, DeSutter TM, Oduor PG, Khan E, 2013. Dissipation and transformation of 17β-estradiol-17-sulfate in soil-water systems. J. Hazard Mater. 260, 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai XL, Acharya K, 2017. Algae-mediated removal of selected pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) from Lake Mead water. Sci. Total Environ. 581, 734–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber LB, Keefe SH, Brown GK, Furlong ET, Gray JL, Kolpin DW, Meyer MT, Sandstrom MW, Zaugg SD, 2013. Persistence and potential effects of complex organic contaminant mixtures in wastewater-impacted streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber LB, Loyo-Rosales JE, Rice CP, Minarik TA, Oskouie AK, 2015. Endocrine disrupting alkylphenolic chemicals and other contaminants in wastewater treatment plant effluents, urban streams, and fish in the Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi River Regions. Sci. Total Environ. 517, 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber LB, Murphy SF, Verplanck PL, Sandstrom MW, Taylor HE, Furlong ET, 2006. Chemical loading into surface water along a hydrological, biogeochemical, and land use gradient: a holistic watershed approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans HE, Goodbred S, Miesner J, Watkins S, Gross T, Denslow N, Choeb T, 1996. Synthetic Organic Compounds and Carp Endocrinology and Histology in Las Vegas Wash and Las Vegas and Callville Bays of Lake Mead, Nevada, 1992 and 1995. US Dept. of the Interior, US Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RA, Furlong ET, 2002. Human-health Pharmaceutical Compounds in Lake Mead, Nevada and Arizona, and Las Vegas Wash, Nevada, October 2000–August 2001. U.S. Geological Survey, Carson City, Nevada. [Google Scholar]

- Brausch JM, Connors KA, Brooks BW, Rand GM, 2012. Humanpharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment: a review of recent toxicological studies and considerations for toxicity testing Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 218, 1–99, 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch JM, Rand GM, 2011. A review of personal care products in the aquatic environment: environmental concentrations and toxicity. Chemosphere 82, 1518–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu QW, Wang B, Huang J, Deng SB, Yu G, 2013. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the aquatic environment in China: a review. J. Hazard Mater. 262, 189–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan MA, Edziyie RE, La Point TW, Venables BJ, 2007. Algal bio-accumulation of triclocarban, triclosan, and methyl-triclosan in a North Texas wastewater, treatment plant receiving stream. Chemosphere 67,1911–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham VL, Binks SP, Olson MJ, 2009. Human health risk assessment from the presence of human pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 53, 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ela WP, Sedlak DL, Barlaz MA, Henry HF, Muir DCG, Swackhamer DL, Weber EJ, Arnold RG, Ferguson PL, Field JA, Furlong ET, Giesy JP, Halden RU, Henry T, Hites RA, Hornbuckle KC, Howard PH, Luthy RG, Meyer AK, Saez AE, vom Saal FS, Vulpe CD, Wiesner MR, 2011. Toward identifying the next generation of superfund and hazardous waste site con-taminants. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JB, 2006. Pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) in urban receiving waters. Environ. Pollut. 144,184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focazio MJ, Kolpin DW, Barnes KK, Furlong ET, Meyer MT, Zaugg SD, Barber LB, Thurman ME, 2008. A national reconnaissance for pharmaceuti-cals and other organic wastewater contaminants in the United States-II) Un-treated drinking water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 402, 201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fram MS, Belitz K, 2011. Occurrence and concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds in groundwater used for public drinking-water supply in California. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3409–3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberer T, 2002. Tracking persistent pharmaceutical residues from municipal sewage to drinking water. J. Hydrol. 266, 175–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel D, Hirsch R, 2002. Statistical Methods in Water Resources Techniques of Water Resources Investigations, Book 4, Chapter A3. U.S. Geological Survey; https://pubs.usgs.gov/twri/twri4a3/pdf/twri4a3-new.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Houtman CJ, 2010. Emerging contaminants in surface waters and their relevance for the production of drinking water in Europe. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 7, 271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Jobling S, Nolan M, Tyler CR, Brighty G, Sumpter JP, 1998. Widespread sexual disruption in wild fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar]

- Jones OAH, Voulvoulis N, Lester JN, 2005. Human pharmaceuticals in waste-water treatment processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 401–427. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado A, Vazquez-Sune E, Carrera J, de Alda ML, Pujades E, Barcelo D, 2012. Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater in Spain: a review of sources, recent occurrence and fate in a European context. Sci. Total Environ. 440, 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpin DW, Furlong ET, Meyer MT, Thurman EM, Zaugg SD, Barber LB, Buxton HT, 2002. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in US streams, 1999–2000: a national reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 1202–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AYC, Reinhard M, 2005. Photodegradation of common environmental pharmaceuticals and estrogens in river water. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 24, 1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb BL, 2008. AP probe finds drugs in drinking water. Ozone Sci. Eng. 30, 173–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lubliner B, Redding M, Ragsdale D, 2010. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Municipal Wastewater and Their Removal by Nutrient Treatment Technologies. Washington State Department of Ecology, Olympia, WA: Publication number 10–03-004. http://www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/1003004.html. [Google Scholar]

- Maida CM, Di Gaudio F, Tramuto F, Mazzucco W, Piscionieri D, Cosenza A, Viviani G, 2017. Illicit drugs consumption evaluation by wastewater-based epidemiology in the urban area of Palermo city (Italy). Annali Dell Istituto Superiore Di Sanita 53,192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroianni N, Lopez-Garcia E, Postigo C, Barcelo D, de Alda ML, 2017. Five-yearmonitoring of 19 illicit and legal substances of abuse at the inlet of a wastewater treatment plant in Barcelona (NE Spain) and estimation of drug consumption patterns and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 609, 916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffe R, de Bustamante I, 2014. Emerging organic contaminants in surface water and groundwater: a first overview of the situation in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 481, 280–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao XS, Bishay F, Chen M, Metcalfe CD, 2004. Occurrence of antimicrobials in the final effluents of wastewater treatment plants in Canada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 3533–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao XS, Koenig BG, Metcalfe CD, 2002. Analysis of acidic drugs in the effluents of sewage treatment plants using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 952, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A, He YL, Jekel M, Reinhard M, Gin KYH, 2014. Emerging contaminants of public health significance as water quality indicator compounds in the urban water cycle. Environ. Int. 71, 46–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patino R, Goodbred SL, Draugelis-Dale R, Barry CE, Foott JS, Wainscott MR, Gross TS, Covay KJ, 2003. Morphometric and histopathological parameters of gonadal development in adult common carp from contaminated and reference sites in Lake Mead, Nevada. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 15, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MR, Alvarez DA, Goodbred SL, Leiker TJ, Patino R, 2010. Sources and distribution of organic compounds using passive samplers in Lake Mead national recreation area, Nevada and Arizona, and their implications for potential effects on aquatic biota. J. Environ. Qual. 39, 1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha SL, Casey FXM, Hakk H, Smith DJ, Padmanabhan G, 2012. Fate and transformation of an estrogen conjugate and its metabolites in agricultural soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 11047–11053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JPR, Lapworth DJ, Nkhuwa DCW, Stuart ME, Gooddy DC, Bell RA, Chirwa M, Kabika J, Liemisa M, Chibesa M, Pedley S, 2015. Emerging contaminants in urban groundwater sources in Africa. Water Res. 72, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulet B, Tauxe A, Tarradellas J, 2002. Analysis of acidic drugs in Swiss waste-waters. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 82, 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Southern Nevada Water Authority, 2015. Water Analysis Summary of Pharmaceuticals and Other Emerging Contaminants. https://www.snwa.com/wq/facts_pharma.html.

- Stan HJ, Heberer T, 1997. Pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. Analusis 25, M20–M23. [Google Scholar]

- Ternes TA, Meisenheimer M, McDowell D, Sacher F, Brauch HJ, Gulde BH, Preuss G, Wilme U, Seibert NZ, 2002. Removal of pharmaceuticals during drinking water treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 3855–3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DC, Jones-Lepp TL, 2013. Emerging contaminant sources and fate in recharged treated wastewater, Lake Havasu city, Arizona. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 19, 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QQ, Ying GG, Pan CG, Liu YS, Zhao JL, 2015. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 6772–6782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.