Abstract

Seven 5-substituted 3-hydrazinyl derivatives of 3a, 4a-diaza-4,4-difluoro-8-phenyl boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) were prepared for use as bioorthogonal fluorescent labels of aldehydes and ketones. The absorption energies can be tuned to absorb visible light over a large span of wavelengths by changing the nature of the 5-substituent. Optical properties of the hydrazones formed with these molecules are affected by the nature of the electrophile such that aliphatic and aromatic hydrazones can be differentiated from each other and from unreacted fluorophore.

Graphical Abstract

Bioorthogonal labeling of biological molecules involves reactions between functional groups not normally present in a biological molecule or system of interest. For example, reactions between azides and phosphine ligands or alkynes have been successfully exploited to tag proteins, nucleic acid polymers and carbohydrates.1 Aldehyde or ketone moiteties can be introduced into many types of biomolecules through chemical means or through genetic manipulation.2–4 Such functional groups can react with hydrazines or hydroxylamines in aqueous solution to form stable hydrazone or oxime products, respectively. Virtually all commercially available fluorophores that react with aldehydes and ketones, however, possess a hydrazide functional group. Hydrazides are less reactive than corresponding hydrazines and tend to form less stable condensation products.5 In this work, we have synthesized a variety of hydrazine-substituted fluorophores that are suitable for use as bioorthogonal labels of aldehydes and ketones.

Boron dipyrromethene-based fluorescent probes (BODIPY® or BDP) have been widely used to probe biological systems. These fluorophores frequently possess large absorption coefficients, high quantum yields and good photostability.6 Emission energies from the visible to the near IR region of the electromagnetic spectrum are accessible through manipulation of the parent molecule.6–9

The absorption and emission energies of the probe are affected by the nature of the substituents on the dipyrromethene and the boron atom.7–11 Recently, Rohand et al. showed that molecule 1 is amenable to substitution at the 3- and 5- positions by a variety of nucleophiles9 and that the photochemical properties of the BDP are highly dependent on the nature of these substitutents.10 We reasoned that putting a hydrazinyl group at this position would lead to a class of probes that should be very useful as labels for suitably functionalized biomolecules. In addition to being more reactive than hydrazide-containing fluorophores, these probes would be expected to undergo changes in absorption and emission properties depending on the electronic nature of the BDP and the electrophile. Such molecules are particularly useful in biological systems such as cells11 in which background fluorescence from unreacted or non-specifically bound reagent can interfere with observation of the covalent product.

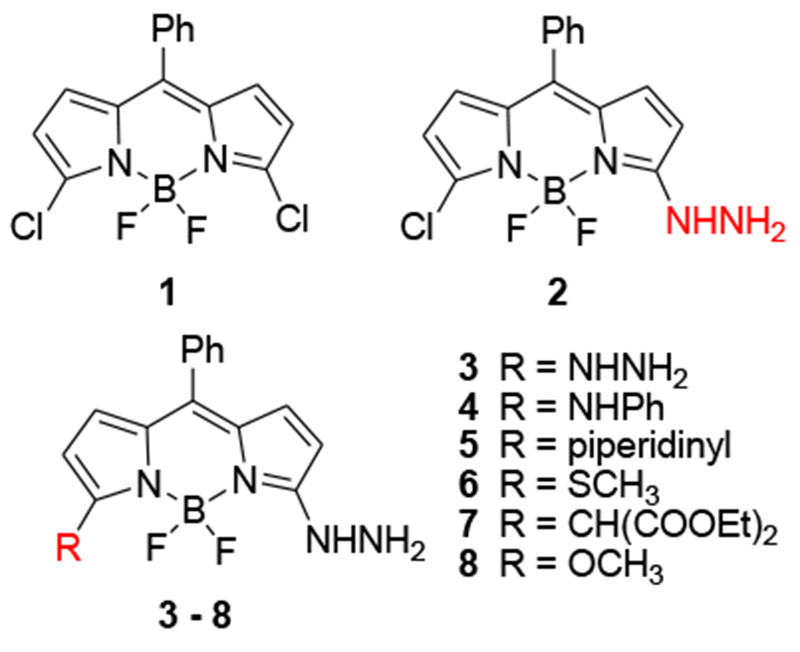

Compound 1 was prepared according to the literature procedure.8 Reaction of 1 with hydrazine under mild conditions cleanly afforded the monohydrazinyl product 2 in good yield (Table 1). Heating the reaction produced the disubstituted product 3 in moderate yield. Compound 2 could serve as a substrate for the preparation of additional monohydrazinyl derivatives (Scheme 1). Moderate to good yields were achieved with nitrogen and sulfur nucleophiles (4, 5, 6). A low yield was obtained when diethylmalonate was employed as a nucleophile (7). A low yield was also obtained when 2 was reacted with sodium methoxide, but this was presumably due to competition between reaction at the 3- and 5- positions, as the major product. of the reaction was 3-chloro-5-methoxy-BDP. Attempts were made to improve the yield, including using 3,5-dimethoxy-BDP as the substrate and hydrazine as the nucleophile. In this case, compound 3 was obtained as the major product. Compound 6 was also synthesized to compare the spectral properties with methoxy-compound 8, but it decomposed so fast due to light and air sensitivity.

Table 1.

Preparation of compounds 2-8

| Nucleophile | Temp (C) | Rxn Time (h) | Product | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrazinea,b | rt | 8.5 | 2 | 85 |

| Hydrazineb | reflux | 5 | 3 | 44 |

| Anilinec | rt | 6.5 | 4 | 87 |

| Piperidinec | rt | 3 | 5 | 57 |

| NaSMec | rt | 8.5 | 6 | 64 |

| Diethylmalonatec | rt | 10 | 7 | 15 |

| NaOMeb | rt | 1 | 8 | 24 |

The substrate for this reaction was compound 1; for all other reactions the substrate was compound 2.

Solvent was methanol.

Solvent was acetonitrile.

Scheme 1.

Structures of BDPs 1-8

Table 1 summarizes the reaction conditions and yields of the hydrazinyl-BDP derivatives.

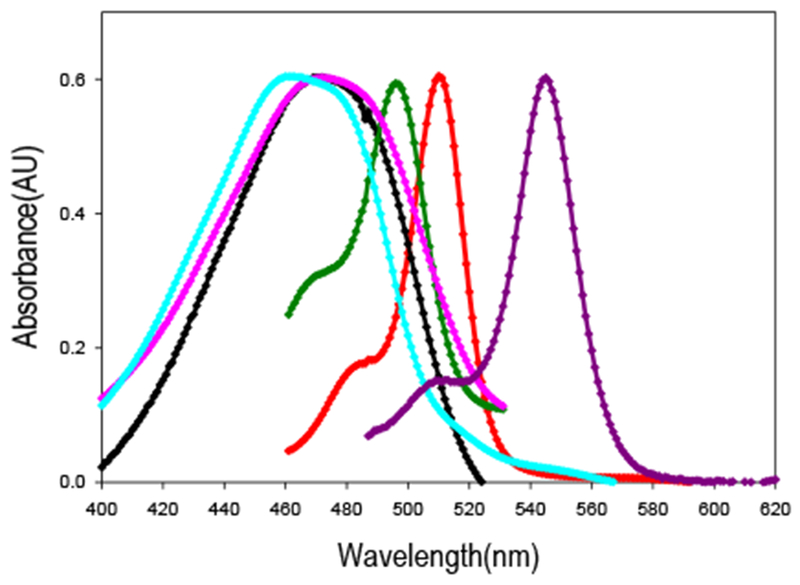

Absorption spectra for compounds 2-8 are shown in Figure 2. Varying the substituent on the 5-position of the 3-hydrazinyl-BPD’s yields absorption maxima that range over 100 nm (450 570 nm in ethanol). Fluorescence emission maxima of the molecules vary over about 60 nm (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Normalized absorption spectra of some compounds in ethanol. From left to right: 7 (cyan), 4 (pink), 2 (black), 8 (dark green),1(red),3(purple).

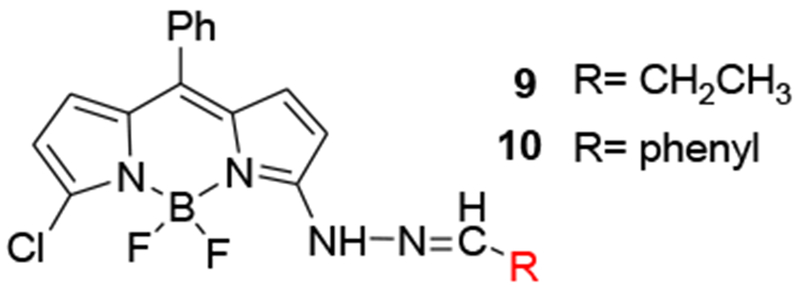

Since the nature of the substituent affects the optical properties of the hydrazine, it was anticipated that hydrazone formation would also affect the absorption and emission spectra of the BDP fluorophore. Model compounds of an aliphatic hydrazone 9 and an aromatic hydrazone 10 were prepared (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Structures of hydrazones of 2

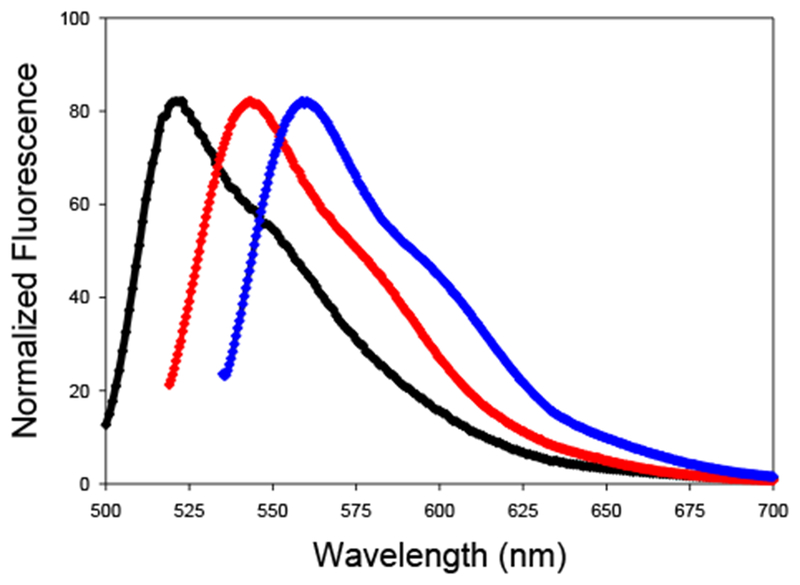

As anticipated, hydrazone formation causes a red shift in the absorption maximum, which is observable by visual inspection of the solution (Figure 3). The red shift is larger for the aromatic hydrazone (478 nm – 531 nm in dioxane) than for the aliphatic hydrazone (478 nm – 513 nm in dioxane). Emission spectra for the hydrazones follow the same pattern (Figure 4). Formation of the aliphatic hydrazone shifts the emission maximum from 522 nm to 543 nm in dioxane, while formation of the aromatic hydrazone red shifts the emission maximum an additional 16 nm. The difference in the energy of the emitted light is also clearly observed by visual inspection (Figure 3). Therefore, background fluorescence due to unreacted hydrazine can be avoided by judicious choice of excitation and emission wavelengths. Covalent labeling of an aromatic aldehyde or ketone, such as a modified phenylalanine or tyrosine, could be distinguished from reactions with aliphatic carbonyls as well as from unreacted reagent.

Figure 3.

Solutions of 2, 9 and 10 in dichloromethane under room light (left) and long wavelength fluorescent light (right).

Figure 4.

Normalized fluorescence emission spectra 2, 9 and 10. From left to right, parent hydrazine 2 (black, λex= 478 nm), aliphatic hydrazone 9 (red, λex= 513 nm), aromatic hydrazone 10 (blue, λex= 531 nm).

The purified and characterized all new BDP derivatives were dissolved in two different solvents to study their spectral properties. All the BDP compounds showed higher quantum yields in apolar solvent, such as dioxane. The shortest wavelength absorption was observed for the monohydrazinyl-BDP product 2, which also had the lowest quantum yields. As compared to 2, compound 3 showed higher quantum yields than the compound 2, because disubstitution on 3 and 5 positions probably changed the photophysics of the molecule, and causing shifts both on absorption and emission spectra. The highest yields were also observed for BDP-hydrazones 9 and 10. This situation can be seen due to the increasing conjugation of the π- system of the fluorophore. Compound 6 and 7 gave also interestingly higher quantum yields compared to other BDP-hydrazines.

In conclusion, 5-substituted 3-hydrazinyl BDP derivatives were prepared for use as bioorthogonal fluorescent labels of aldehydes and ketones. The absorption energies can be tuned to absorb visible light over a large span of wavelengths by changing the nature of the substituent. Optical properties of the hydrazones formed with these BDP’s are conducive to selective labeling. Formation of a hydrazone shifts absorption and emission maxima of the probe to longer wavelength; therefore, the fluorescent signal from the covalently bound fluorophore is observable in the presence of unreacted material. A hydrazone formed with an aliphatic aldehyde has different absorption and emission maxima than one formed with an aromatic aldehyde. Thus, a hydrazone formed by reaction with an unnatural amino acid such as a derivatized phenylalanine or tyrosine should yield a distinct fluorescent signal, even if other carbonylated species are present. Labeling project is under progress in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Absorption and fluorescence emission spectral data of compounds 2-10 in dioxane and methanol.

| Compound | Solvent | λabsmax (nm) |

λemmax (nm) |

ФF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Dioxane | 478 | 522 | 0.004 |

| 2 | Methanol | 463 | 529 | 0.002 |

| 3 | Dioxane | 549 | 567 | 0.136 |

| 3 | Methanol | 546 | 564 | 0.023 |

| 4 | Dioxane | 487 | 545 | 0.027 |

| 4 | Methanol | 475 | 539 | 0.018 |

| 5 | Dioxane | 486 | 526 | 0.016 |

| 5 | Methanol | 473 | 523 | 0.010 |

| 6 | Dioxane | 535 | 563 | 0.183 |

| 6 | Methanol | 525 | 559 | 0.094 |

| 7 | Dioxane | 486 | 522 | 0.105 |

| 7 | Methanol | 460 | 517 | 0.046 |

| 8 | Dioxane | 500 | 516 | 0.034 |

| 8 | Methanol | 495 | 511 | 0.012 |

| 9 | Dioxane | 513 | 543 | 0.108 |

| 9 | Methanol | 502 | 539 | 0.064 |

| 10 | Dioxane | 531 | 559 | 0.214 |

| 10 | Methanol | 521 | 555 | 0.098 |

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Jürgen Schulte for collecting 11B NMR spectra and David Tuttle for photography. We also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Rebecca Kissling for her scientific and personal support. Financial support from NIH (R01 CA69571) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

Experimental procedures and characterization data for 2 - 10.

References:

- (1).Agard NJ; Baskin JM; Prescher JA; Lo A; Bertozzi CR, ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zatsepin TS; Stetsenko DA; Gait MJ; Oretskaya TS, Bioconjug. Chem. 2005, 16, 471–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cornish VW; Hahn KM; Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8150–8151. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang ZW; Smith BAC; Wang L; Brock A; Cho C; Schultz PG, Biochemistry 2003, 42, 6735–6746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sayer J; Peskin M; Jencks W, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 4277–4287. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ziessel R; Ulrich G; Harriman A, New J. Chem 2007, 31, 496–501. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Thoresen LH; Kim HJ; Welch MB; Burghart A; Burgess K, Synlett 1998, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rohand T; Qin WW; Boens N; Dehaen W Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 4658–4663. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rohand T; Baruah M; Qin WW; Boens N; Dehaen W, Chem. Commun. 2006, 266–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Qin WW; Rohand T; Baruah M; Stefan A; Van der Auweraer M; Dehaen W; Boens N, Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 420, 562–568. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lemieux GA; de Graffenried CL; Bertozzi CR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4708–4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.