Abstract

Previous research has repeatedly shown both personality and psychological stress to predict gastrointestinal disorders and chronic diarrhea in humans. The goal of the present research was to evaluate the role of personality, as well as psychological stressors (i.e., housing relocations and rearing environment), in predicting chronic diarrhea in captive rhesus macaques, with particular attention to how personality regulated the impact of such stressors. Subjects were 1,930 rhesus macaques at the California National Primate Research Center reared in a variety of environments. All subjects took part in an extensive personality evaluation at approximately 90–120 days of age. Data were analyzed using generalized linear models to determine how personality, rearing condition, housing relocations, and personality by environment interactions, predicted both diarrhea risk (an animal’s risk for having diarrhea at least once) and chronic diarrhea (how many repeated bouts of diarrhea an animal had after their initial bout). Much like the human literature, we found that certain personality types (i.e., nervous, gentle, vigilant, and not confident) were more likely to have chronic diarrhea, and that certain stressful environments (i.e., repeated housing relocations) increased diarrhea risk. We further found multiple interactions between personality and environment, supporting the “interactionist” perspective on personality and health. We conclude that while certain stressful environments increase risk for chronic diarrhea, the relative impact of these stressors is highly dependent on an animal’s personality.

Keywords: primate, diarrhea, personality, temperament, macaque

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diarrhea is a persistent problem in primate facilities, and has been reported to occur in 3.6–31.6% of individuals in various macaque subpopulations in captivity (Hird, Anderson, & Bielitzki, 1984; Munoz-Zanzi, Thurmond, Hird, & Lerche, 1999; Prongay, Park, & Murphy, 2013; Russell et al., 1987; Wilk, Maginnis, Coleman, Lewis, & Ogden, 2008). Monkeys experiencing chronic diarrhea are prone to dehydration, weight loss, and malnutrition, which if untreated can lead to death or the need for humane euthanasia (Holmberg et al., 1982; Howell et al., 2012; Munoz-Zanzi et al., 1999; Wilk et al., 2008). Chronic diarrhea associated mortality in captive macaques reportedly occurs in 3.2% of outdoor housed animals (Prongay et al., 2013), and, in the past, has accounted for up to 34% of non-experimental deaths at some facilities (Holmberg et al., 1982). Although diarrhea in macaques has been correlated with the enteric pathogens Campylobacter spp. (Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni species), Shigella flexneri, Yersinia enterocolitica and Strongyloides fulleborni (Sestak et al., 2003), many cases are believed to be non-pathogenic and of unknown origin (Holmberg et al., 1982; Russell et al., 1987; Wilk et al., 2008). With the direct cause of diarrhea often unknown, determining which individuals may be at high risk is a key step in preventing and managing this problem.

Psychological stress and stressful life events have long been predictive of gastrointestinal disorders and associated bouts of chronic diarrhea in humans (For reviews see Maunder, 2005; Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005). In retrospective surveys, for example, stressful life events and emotional disturbance have been shown to frequently occur prior to the onset and exacerbation of gastrointestinal disorders (Fava & Pavan, 1977; Mc Kegney, Gordon, & Levine, 1970; Tocchi et al., 1997; Whybrow, Kane, & Lipton, 1968). Prospective studies with human patients have similarly shown stressful life events to positively predict exacerbation of gastrointestinal disorders, as well as onset of acute episodes of diarrhea (Bennett, Tennant, Piesse, Badcock, & Kellow, 1998; Bitton, Sewitch, Peppercorn, Edwardes, & Shah, 2003; Duffy et al., 1991; Garrett, Brantley, Jones, & McKnight, 1991; Greene, Blanchard, & Wan, 1994). Furthermore, short term stress has experimentally induced colonic motility in humans (Rao, Hatfield, Suls, & Chamberlain, 1998), and gastrointestinal inflammation in animal models (S. M. Collins et al., 1996; Gue et al., 1997; Qiu, Vallance, Blennerhassett, & Collins, 1999).

There are many pathways by which psychological stress can affect gastrointestinal function. Broadly speaking, chronic exposure to stress can have generalized immunosuppressive actions on the body, putting individuals at higher risk for gastrointestinal disorders, as well as enteric pathogen colonization and growth (Bailey & Coe, 1999; Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005; Sapolsky, Romero, & Munck, 2000). Acute stressors can increase intestinal mucin and ion secretion, increase epithelial permeability, and induce intestinal inflammation, triggering individual episodes of diarrhea and reactivating pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders (Stephen M Collins, 2001; Hart & Kamm, 2002; Maunder, 2005).

Although many previous studies have focused on the relationship between stressful events and diarrhea, it is likely to be an individual’s perception of events that truly predicts their specific risk (Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005). When using the “Perceived Stress Questionnaire” (PSQ), a measure of individual perceived stress developed specifically for psychosomatic research (Levenstein et al., 1993), Levenstein and colleagues found PSQ better predicted exacerbation of colitis than specific stressful life events (Levenstein et al., 2000). Thus if multiple individuals experience the same life event (e.g., loss of a job), it is the individuals that perceive this event as particularly stressful and challenging that are at highest risk for disorder onset or exacerbation. Therefore two individuals that experience the same event are at different risk for chronic diarrhea depending on individual differences in how they perceive the event.

Personality, defined as an individual’s basic position towards environmental change and challenge that emerges early in life and typically remains consistent throughout development (Coleman, 2012), can account for many observed differences in individual response to environmental stressors. Research on human personality has reliably demonstrated a correlation between personality and gastrointestinal disorders; individuals are generally at greater risk if they are highly neurotic, introverted, nervous, and/or anxious (Robertson, Ray, Diamond, & Edwards, 1989; Tanum & Malt, 2001; Tocchi et al., 1997). Personality has been extensively studied in captive rhesus macaques (for a review see Freeman & Gosling, 2010), and has been used to reliably predict multiple health-related outcomes, including disease progression (Capitanio et al., 2008; Capitanio, Mendoza, & Baroncelli, 1999), immune function (Capitanio, 2011; Sloan, Capitanio, Tarara, & Cole, 2008), and HPA activity (Capitanio, Mendoza, & Bentson, 2004). Similar to humans, personality may predict gastrointestinal disease in rhesus macaques; colitis was recently shown to occur more frequently in adult rhesus that were below average in the personality measures of hostility, gregariousness, exploration, detachment, and sensitivity (Howell et al., 2012).

At an early age captive rhesus macaques can face a wide range of environmental stressors, which are largely determined by their rearing environment. Rhesus are traditionally raised in either outdoor social groups, or indoors in relatively small controlled environments that provide limited social interactions. Each rearing environment presents a unique set of life stressors and adversities: while group housed outdoor animals face social challenges such as aggression and establishment of social hierarchies (Flack & de Waal, 2004), indoor animals may lack proper socialization, and face potentially stressful day-to-day husbandry events such as cage cleaning and health checks (Line, Markowitz, Morgan, & Strong, 1991), as well as more invasive procedures such as blood draws and veterinary procedures necessary for health or research purposes (Novak, 2003; Rommeck, Anderson, Heagerty, Cameron, & McCowan, 2009). Indoor rearing and housing has been shown to be a risk factor for behavioral problems indicative of psychological stress such as motor stereotypic behaviors and self-abusive behaviors (Gottlieb, Capitanio, & McCowan, 2013; Novak, Meyer, Lutz, & Tiefenbacher, 2006; Rommeck et al., 2009). Similarly, reported rates of diarrhea are higher in animals raised and housed indoors compared to those in outdoor social groups (Hird et al., 1984). Among indoor raised monkeys, those reared in a nursery (i.e., separated from their dam at an early age) are at highest risk of developing chronic diarrhea (Elmore, Anderson, Hird, Sanders, & Lerche, 1992; Hird et al., 1984; but see Elfenbein et al., 2016, who propose that gestation location, rather than postnatal environment, per se, may be the more important factor for indoor-reared monkeys). When housed outdoors, monkeys show the lowest rates of diarrhea in large social groups (i.e., 125–250 animals) compared to smaller social groups (i.e., 22–54 animals) (Prongay et al., 2013).

Regardless of an individual’s rearing environment, it is common for captive rhesus macaques to be temporarily or permanently removed from their current housing environment, (Capitanio & Lerche, 1998). Monkeys may be relocated due to injuries, illness, assignment to projects, or general colony management needs. These relocations can occur fairly frequently, and are believed to be a potentially stressful life event (Capitanio & Lerche, 1998). Experimentally relocating an animal to a novel environment can elevate corticosteroid secretion, disrupt sleep patterns, and decrease appetite and activity (Crockett, Bowers, Sackett, & Bowden, 1993; Crockett et al., 1995; Mitchell & Gomber, 1976; Phoenix & Chambers, 1984). Management related relocations have been shown to positively predict the development of abnormal behaviors (Gottlieb et al., 2013; Rommeck et al., 2009), and progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease (Capitanio & Lerche, 1998), and thus are believed to represent a source of stress in captivity.

Personality does not always uniformly predispose individuals to specific health outcomes. Rather, from an “interactionist” perspective, personality may only influence disease when combined with factors such as stress and other environmental conditions (Eysenck, 1991). The goal of the present research was to evaluate the role of personality and environmental stressors in predicting chronic diarrhea in captive rhesus macaques. We hypothesized that individual personality, rearing environment and relocations would all predict chronic diarrhea in rhesus macaques. More importantly, although some personality types may generally place monkeys at higher risk for chronic diarrhea, we hypothesized that the relative impact of rearing environment and relocations would be highly dependent on an individual’s personality, supporting the interactionst perspective on human health and personality. Therefore, to more accurately capture the effect of personality on diarrhea, we further evaluated interactions between personality and rearing environment and relocations.

METHODS

All subjects were cared for in compliance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California Davis, adhered to the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act and US Department of Agriculture regulations (USDA, 1991) and adhered to the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Non Human Primates.

Data Collection

Subjects were 1,930 (791 male and 1129 female) rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) born at the CNPRC between January 2001 and August 2007. All bouts of diarrhea were coded from the date of birth through to the end date (see next paragraph) by examining computerized and hand-written health records for animals. A diarrhea bout began when an animal was relocated into the hospital to treat diarrhea, or treated for diarrhea in their current location (e.g., anti-biotic treatment, sub-Q fluids, supplements, etc.), and ended when the animal was released by veterinary staff. When an animal was given a second round of antibiotics without having been released, this was counted as the same bout.

Data were collected on each individual until they a) were put on a research project, b) were shipped to another facility, c) died or were euthanized for health reasons, or d) reached August 1st of their third year at the CNPRC (animals are typically born between February and August, therefore data collection ended at the latest when animals were between 35 and 42 months old). For all analyses, individual animal time in the study was included as a covariate or offset.

Subjects were raised in one of four conditions: field cage, corn crib, indoor mother reared, or nursery reared. Field cages are large ½ acre outdoor enclosures that house approximately 50–200 animals, while corn cribs are roughly 400 square foot outdoor enclosures that house approximately 15–30 animals. Field cage and corn crib reared animals were raised in their respective outdoor enclosure with their biological or foster mother. Indoor mother reared and nursery reared animals were raised indoors with no social group. Indoor mother reared animals were housed in a cage with their biological or foster mother, and at most one additional adult female and infant macaque pair. Nursery reared animals were individually housed until 3 weeks of age, at which time they were given visual access to an infant of the same age, and eventually paired with this peer at 5 weeks. [We note that there is overlap in subjects for indoor mother- and nursery-reared animals with analyses reported by Elfenbein et al., 2016, which focused on gestation location and other variables on diarrhea rates for indoor-reared animals. For the present analysis, we have retained those animals in order to make a direct comparison between all four rearing conditions. We note in the appropriate places below when our results duplicate those of Elfenbein et al., 2016, to insure the reader does not regard our results for these animals as an independent replication].

Relocation data were collected from an internal Oracle database of animal histories. A relocation was defined as any instance in which an individual was relocated from an outdoor cage (field cage or corn crib) to an indoor room, from an indoor room to an outdoor cage, or from one indoor room to new indoor room. Relocations were not included in the analysis if they were into or out of hospital rooms, as they may have been directly caused by an episode of diarrhea, or if they were from one cage in a room to another cage in the same room.

Personality data were collected from a BioBehavioral Assessment (BBA) that took place between the ages of approximately 90–120 days. The procedures involved in the BBA have previously been described in detail (Capitanio, 2017; Golub, Hogrefe, Widaman, & Capitanio, 2009); briefly, infants were temporarily separated from their mothers and/or social partners and relocated to individual indoor cages for the 25-hour testing period, where they took part in multiple behavioral and physiological assessments. We focused on three sets of measures that reflect different aspects of personality – a) behavioral responsiveness to being in a novel environment alone, b) extent to which animals interacted with an unfamiliar and novel object, and c) ratings of overall temperament, based on the impressions of the technician who conducted the assessments. (see Table 1 for a full list of personality measures included in the analyses).

Table 1:

Personality and temperament measurements from BioBehavioral Assessment

| BBA Measurement | Variable Measured | Definition of Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Holding Cage Score | Day 2 Activity | Factor score comprised of the following variables from day 2 of testing: locomotion, not hanging from top/side of cage, environmental explore, eat, drink, crouch |

| Day 2 Emotionality | Factor score comprised of the following variables from day 2 of testing: vocal coo, vocal bark, scratch, threat, lipsmack | |

| Novel Object Response | Novel Object Contact | Mean number of 15-second intervals in which the subject touched novel object during an average 5-minute period during the daytime |

| Temperament Score | Gentle | Factor score comprised of the following temperament ratings: gentle, calm, flexible, curious |

| Vigilant | Factor score comprised of the following temperament ratings: vigilant, not depressed, not tense, not timid | |

| Confident | Factor score comprised of the following temperament ratings: confident, bold, active, curious, playful | |

| Nervous | Factor score comprised of the following temperament ratings: nervous, fearful, timid, not calm, not confident |

For details on factor analyses and methods, see Golub et al. [2009].

Each individual’s behavioral responsiveness to the relocation and 25-hr period in the holding cage was indicated by scores for “activity” and “emotionality” for Day 1 and Day 2 of the testing period. Scores were created based on 5-minute focal animal observations performed by a single live observer at the beginning (Day 1) and end (Day 2) of the 25-hour period. The observer recorded multiple behaviors, including both activity states and events, and exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses indicated a two-factor model described the data well, and factor scores were computed for each factor (named “Activity” and Emotionality;” see Table 1 for a listing of component behaviors) for Day 1 and for Day 2 (Golub et al., 2009). Day 2 Activity and Emotionality scores represent an animal’s ability to adapt to the temporary BBA testing situation, and may reflect a broader ability to cope with environmental change. For example, although substantial variation exists, by Day 2, animals generally reduce the amount of time they spend hanging from the side of the cage, and increase their locomotion and eating (all are measures of Activity); similarly, animals also show less cooing and threatening, and more scratching (all are measures of Emotionality) on Day 2 compared to Day 1, suggesting development of a more regulated emotional response to the situation. In our analyses we specifically evaluated Activity and Emotionality scores from only Day 2.

Responses to a novel object were assessed by placing a small, cylindrical plastic object (3.5” length × 1.5” diameter) containing an accelerometer into the cage. The object was available immediately when the animals were placed in their cages. Novel object use was recorded as the mean proportion of 15-second intervals in which the subject touched the object during an average 5-minute period between 9:45AM – 4:20PM.

At the end of the 25-hour period the technician who performed the tests and handled the infants scored each individual on a 7-point Likert scale for multiple behavioral measures of temperament. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis indicated that these behavioral measures could be well described by a four-factor model of temperament: “Gentle,” “Vigilant,” “Confident,” and “Nervous” (Golub et al., 2009) (for a detailed description of each factor see Table 1).

All personality measures, except novel object scores, were z-scored across all subjects in each given year. Therefore the average score for each personality measure is approximately 0, with a SD of 1.

Analyses

Data were analyzed using two distinct modeling frameworks. In the first model, the outcome was a dichotomous (yes/no) indicator of whether an animal ever had a bout of diarrhea over the observation period. This model utilized all subjects (N=1930), including animals housed in corn cribs, field cages, and indoor cages. This model estimates an animal’s risk of ever having a bout of diarrhea, and is not necessarily representative of chronic diarrhea; we refer to this as Model 1: Diarrhea Risk. After being treated for diarrhea some animals remain healthy, while others repeatedly return to the hospital for diarrhea and dehydration. To evaluate risk of chronic diarrhea, the second model’s outcome was count of diarrhea after an individual’s 1st diarrhea case (e.g., if an animal had 3 bouts of diarrhea this would count in the model as 2 repeated bouts of diarrhea). This model utilized only subjects who had diarrhea at least once over the course of the study (N=693). Since the age at first diarrhea varied between monkeys, the time remaining on study after first diarrhea was different for each subject. To account for this inequality, “total days on project after first diarrhea” was included in the model as an offset. On average, subjects were on project for 634 ± SD 392 days after first diarrhea. We refer to the second model as Model 2: Chronic Diarrhea.

All data were analyzed by fitting generalized linear models, using “glm” function in R (R, version 3.0.2, the R Foundation). For each model, variable selection was performed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), a popular information criterion used to compare candidate models, in which models are rewarded for goodness of fit and penalized for over-complexity (Akaike, 1987). Predictors were dropped iteratively until deleting predictors would increase the AIC beyond the AIC of the saturated model. Once the final models were selected, remaining variables with a P-value equal to or less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All P-values were calculated by the Wald procedure, and correspond to two-sided tests. For a full list of variables included in the full models see Table 2. Diarrhea Risk (Model 1) was analyzed assuming a binomial distribution for the outcome variable presence/absence of diarrhea over the course of the study. Chronic Diarrhea (Model 2) was analyzed assuming a Poisson distribution for the outcome variable count of diarrhea after initial bout. For both analyses, the variable “relocations” was centered on the average number of relocations for the sample (Model 1: 4.22, Model 2: 3.06).

Table 2:

List of variables included in the full models.

| Sex |

| Rearing Condition |

| Relocations |

| Day 2 Activity |

| Day 2 Emotionality |

| Novel Object Contact |

| Gentle |

| Vigilant |

| Confident |

| Nervous |

| Rearing Condition X Day 2 Activity |

| Rearing Condition X Day 2 Emotionality |

| Rearing Condition X Novel Object Contact |

| Rearing Condition X Gentle |

| Rearing Condition X Vigilant |

| Rearing Condition X Confident |

| Rearing Condition X Nervous |

| Relocations X Day 2 Activity |

| Relocations X Day 2 Emotionality |

| Relocations X Novel Object Contact |

| Relocations X Gentle |

| Relocations X Vigilant |

| Relocations X Confident |

| Relocations X Nervous |

| Age at End of Study (Model 1 only) |

| Days indoors (Offset, Model 2 only). |

Variables in italics are interaction terms.

RESULTS

Rates of Diarrhea

Of the 1,930 subjects, 693 (36%) had at least one bout of diarrhea. Of the 693 subjects that had diarrhea, on average each subject had 2.01± SD 1.58 bouts of diarrhea. For a full list of rates of diarrhea by rearing environment see Table 3.

Table 3:

Rates of diarrhea by rearing condition and sex.

| Variable | N | Subjects with diarrhea (%) | Average count of diarrhea (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rearing Condition | |||

| Field Cage | 1456 | 474 (33%) | 1.82 (1.38) |

| Corn Crib | 160 | 55 (34%) | 1.89 (1.62) |

| Indoor Mother | 97 | 50 (52%) | 2.86 (2.33) |

| Nursery | 217 | 114 (53%) | 2.46 (1.71) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 728 | 411 (36%) | 2.01 (1.59) |

| Male | 509 | 282 (36%) | 2.01 (1.55) |

| Study Population | 1930 | 693 (36%) | 2.01 (1.58) |

Average count of diarrhea and corresponding standard errors (SE) are calculated using only animals that were recorded having diarrhea at least once.

Diarrhea Models

All reported results are assuming any variables not discussed are held constant. Unless otherwise noted, references to the “average” monkey refer to monkeys that were field cage reared with average temperament scores and average number of relocations.

Model 1: Diarrhea Risk

The final model for diarrhea risk (i.e., an animal’s risk for having diarrhea over the course of the study) included main effects for the measures Vigilant, Gentle, Confident, Nervous, and daytime Novel Object Contact, as well as rearing condition and relocations. The model also included interaction terms between relocations and the four temperament measures, as well as an interaction term between Nervous and rearing condition. The variable “sex” was not included in the final model, nor were the measures Day 2 Activity or Emotionality. For a full list of parameter estimates, standard errors, and corresponding P-values, see Table 4.

Table 4:

Variables included in the final models for diarrhea risk and diarrhea count together with parameter estimates, corresponding standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values.

| Variable | ß Estimate (SE) | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Diarrhea Risk. Diarrhea (Yes/No) ~ vigilant, gentle, confident, nervous, contact novel object, relocations, rearing, age, relocations x vigilant, relocations x gentle, relocations x confident, relocations x nervous, rearing x nervous | ||||

| Vigilant score | 0.02 (0.08) | −0.14 | 0.17 | 0.81 |

| Gentle score | −0.003 (0.08) | −0.16 | 0.15 | 0.96 |

| Confident score | 0.07 (0.08) | −0.09 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| Nervous score | −0.02 (0.08) | −0.18 | 0.15 | 0.84 |

| Novel object contact | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Relocations | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.10 | 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| Rearing | ||||

| Field Cage | – | – | – | – |

| Corn Crib | −0.36 (0.21) | −0.76 | 0.05 | 0.84 |

| Indoor Mother | 0.13 (0.24) | −0.35 | 0.61 | 0.58 |

| Nursery | 0.16 (0.25) | −0.32 | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| Relocations x Vigilant score | −0.05 (0.03) | −0.11 | 0.004 | 0.07 |

| Relocations x Gentle score | −0.07 (0.03) | −0.13 | −0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Relocations x Confident score | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.02 | 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| Relocations x Nervous score | −0.09 (0.03) | −0.15 | −0.02 | < 0.05 |

| Corn Crib x Nervous score | −0.37 (0.19) | −0.75 | 0.01 | 0.054 |

| Indoor Mother x Nervous score | 0.13 (0.20) | −0.26 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| Nursery x Nervous score | 0.62 (0.21) | 0.20 | 1.04 | < 0.01 |

| Model 2: Diarrhea Count. Diarrhea Count ~ vigilant, gentle, confident, nervous, day 2 activity, day 2 emotionality, novel object contact, relocations, rearing, relocations x confident, relocations x day 2 activity, relocations x day 2 emotionality, relocations x novel object contact, rearing x gentle, rearing x confident, rearing x day 2 activity, rearing x day 2 emotionality, rearing x gentle, rearing x novel object contact | ||||

| Vigilant score | 0.24 (0.07) | 0.10 | 0.38 | < 0.001 |

| Gentle Score | 0.22 (0.08) | 0.06 | 0.38 | < 0.01 |

| Confident Score | −0.18 (0.09) | −0.36 | 0.00 | < 0.05 |

| Nervous Score | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.01 | 0.25 | < 0.05 |

| Day 2 Activity | 0.1 (0.06) | −0.02 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| Day 2 Emotionality | −0.05 (0.05) | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

| Novel Object Contact | −0.11 (0.04) | −0.19 | −0.03 | < 0.01 |

| Relocations | 0.06 (0.04) | −0.02 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Rearing | ||||

| Field Cage | – | – | – | – |

| Corn Crib | −0.4 (0.37) | −1.13 | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| Indoor Mother | 0.56 (0.3) | −0.03 | 1.15 | 0.06 |

| Nursery | 0.38 (0.26) | −0.13 | 0.89 | 0.15 |

| Relocations x Confident score | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.09 | < 0.01 |

| Relocations x Day 2 Activity | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.09 | < 0.05 |

| Relocations x Day 2 Emotionality | 0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Relocations x Novel Object Contact | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.04 | 0.00 | < 0.05 |

| Corn Crib x Confident Score | 0.66 (0.29) | 0.09 | 1.23 | < 0.05 |

| Corn Crib x Day 2 Activity | 0.29 (0.22) | −0.14 | 0.72 | 0.18 |

| Corn Crib x Day 2 Emotionality | −0.38 (0.22) | −0.81 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Corn Crib x Gentle Score | −0.03 (0.22) | −0.46 | 0.4 | 0.89 |

| Corn Crib x Novel Object Contact | 0.02 (0.1) | −0.18 | 0.22 | 0.85 |

| Indoor Mother x Confident Score | −0.11 (0.2) | −0.5 | 0.28 | 0.57 |

| Indoor Mother x Day 2 Activity | −0.46 (0.19) | −0.83 | −0.09 | < 0.05 |

| Indoor Mother x Day 2 Emotionality | 0.38 (0.18) | 0.03 | 0.73 | < 0.05 |

| Indoor Mother x Gentle Score | −0.05 (0.19) | −0.42 | 0.32 | 0.79 |

| Indoor Mother x Novel Object Contact | 0.21 (0.08) | 0.05 | 0.37 | < 0.01 |

| Nursery x Confident Score | −0.09 (0.16) | −0.4 | 0.22 | 0.58 |

| Nursery x Day 2 Activity | −0.25 (0.18) | −0.6 | 0.1 | 0.16 |

| Nursery x Day 2 Emotionality | −0.17 (0.17) | −0.5 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Nursery x Gentle Score | −0.63 (0.15) | −0.92 | −0.34 | < 0.001 |

| Nursery x Novel Object Contact | 0.12 (0.08) | −0.04 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

Baseline factor levels for categorical variables are indicated with a dash. Relocations has been centered at 4.22. Age at end of study was included in model 1 as a covariate, and time indoors was included in model 2 as an offset, but are not included in the table.

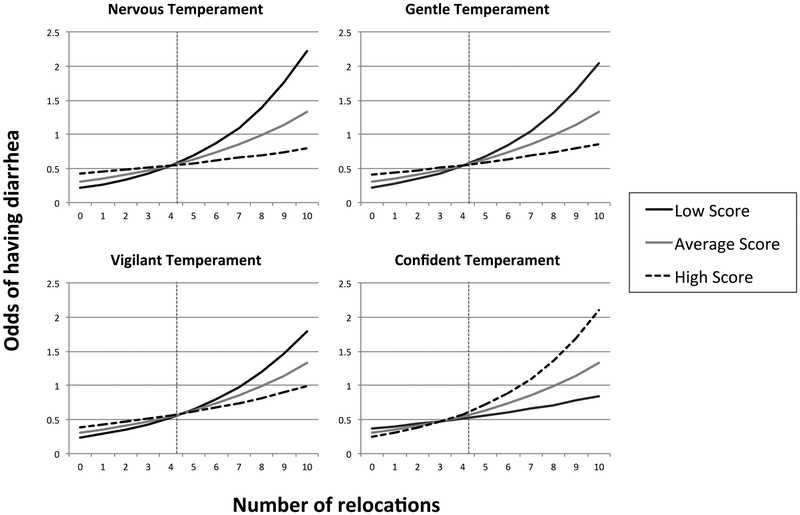

There were no significant main effects for any of the temperament measures (P > 0.05, exact P-values given in Table 4). The variable Novel Object Contact was a near-significant predictor (P = 0.06), with subjects that had higher novel object contact less likely to have diarrhea than subjects with identical scores on all other variables. Number of relocations was a significant predictor of diarrhea risk (P < 0.001). On average each subject had 4.22 ± SD 2.67 relocations during this study. For an animal with average temperament measures, odds of having diarrhea increased by 0.16 for each relocation. The impact of relocations was significantly affected by temperament: there were significant interactions between relocations and temperament measures Gentle (P < 0.01), Confident (P < 0.05), and Nervous (P < 0.05), as well as an interaction between relocations and Vigilant that approached significance (P = 0.07). As Figure 1 indicates, a higher count of relocations increased the odds of ever having diarrhea, particularly for animals that were low on Nervous, Gentle, and Vigilant temperament, and for animals that were high on Confident temperament.

Figure 1:

Interaction between temperament and relocations for odds of having diarrhea based on fitted model in Table 4: Each plots includes three curve representing the odds of having diarrhea with low, average, or high scores of the respective temperament. Low and high temperament scores are calculated as one standard deviation below or above average temperament of the study population. The vertical lines indicate the average number of relocations in the study population (4.22 relocations). Odds are determined assuming animals are field cage reared, and are average for other personality measures and time on project.

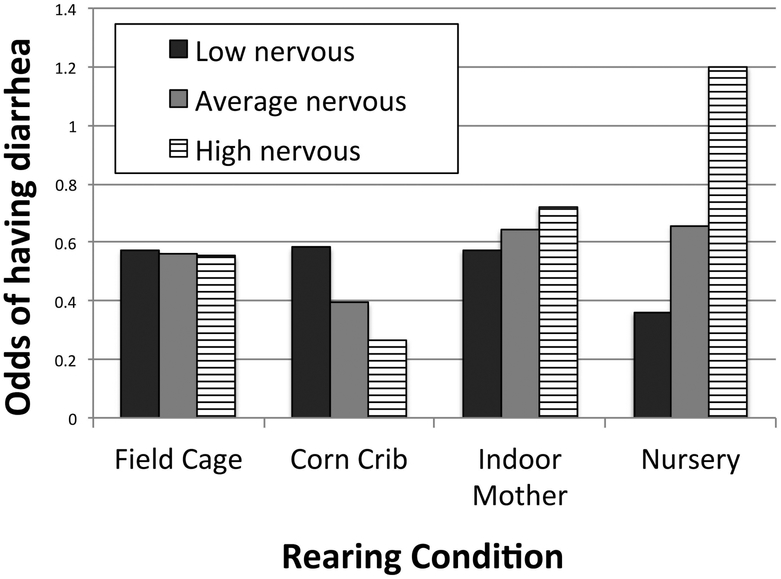

There were no significant main effects of rearing condition on risk of diarrhea, however there was a significant interaction between nursery rearing and the temperament measure Nervous (P < 0.001); Figure 2 indicates that for the average nursery-reared animal, the odds of ever having diarrhea were greatest for animals high on Nervous temperament (this result was also reported by Elfenbein et al., 2016). The analysis also revealed that the interaction between corn crib rearing and nervous approached significance (P = 0.054).

Figure 2:

Interaction between nervous temperament and rearing condition for odds of having diarrhea based on fitted model in Table 4: For each rearing condition, odds of having diarrhea are displayed for animals with low, average, and high values of nervous temperament. Low and high temperament score are calculated as one standard deviation below or above average nervous temperament of the study population. Odds are determined assuming animals are average for other personality measures, as well as number of relocations, and time on project.

Model 2: Chronic Diarrhea

The final model for chronic diarrhea (i.e., how many repeat cases of diarrhea an animal was expected to have after their initial bout) included main effects for the temperament measures Vigilant, Gentle, Confident, Nervous, Day 2 Activity, Day 2 Emotionality, Novel Object Contact, as well as rearing condition and relocations. The model also included a number of interaction terms. The variable “sex” was not included in the final model. For a full list of parameter estimates, standard errors, and corresponding P-values, see Table 4.

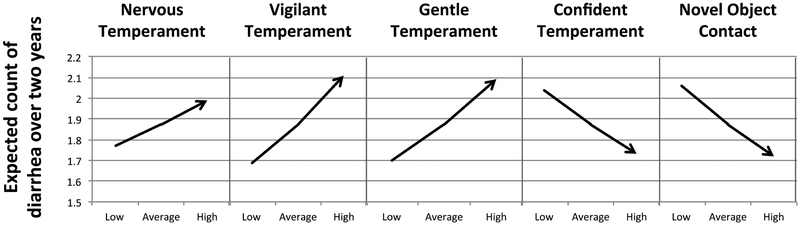

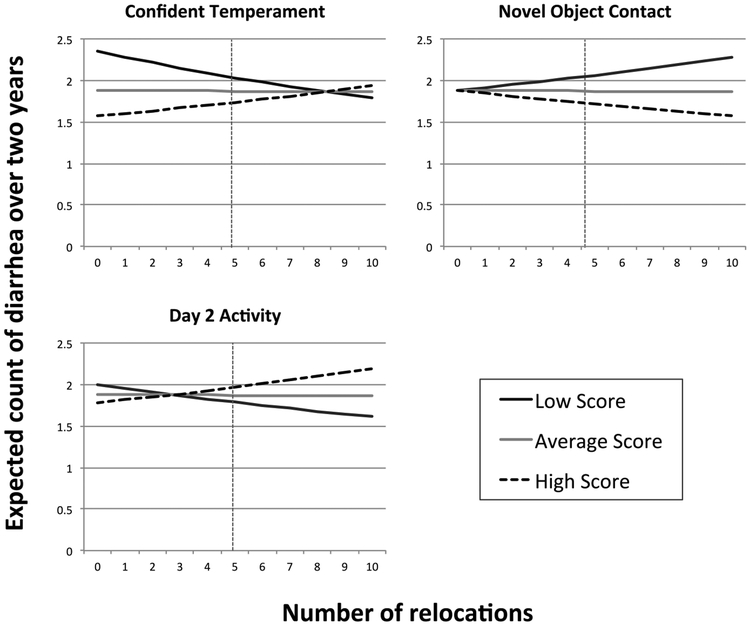

There were significant main effects of the temperament measures Vigilant (P < 0.001), Gentle (P < 0.001), Confident (P < 0.001), Nervous (P < 0.001), and Novel Object Contact (P < 0.001) on expected count of diarrhea. The average subject (i.e., field cage reared with average number of relocations) was more likely to have repeated diarrhea if they had high Vigilant, Gentle, and/or Nervous scores, while they were at lower risk with high Confident and/or Novel Object Contact scores (Figure 3). Number of relocations approached significance (P = 0.08), with expected count of diarrhea increasing by 6% for each relocation for animals with average temperament scores. On average each subject had 3.06 ± SD 2.84 relocations during this study. The impact of relocations was significantly affected by temperament: there were significant interactions between relocations and the measures Confident (P < 0.01) Day 2 Activity (P < 0.05), and Novel Object Contact (P < 0.05), with the interaction between relocations and Day 2 Emotionality approaching significance (P = 0.09). As Figure 4 suggests, for otherwise average animals that experienced very few relocations, repeated bouts of diarrhea were more frequent among animals that were low in Confidence. For otherwise average animals that experienced a high number of relocations, repeated bouts of diarrhea were more frequent in animals that were low on Novel Object Contact and that were high on Day 2 Activity.

Figure 3:

Main effects of temperament on expected count of diarrhea over two years based on the fitted model in Table 4: Low and high temperament score are calculated as one standard deviation below or above average temperament of the study population. Expected counts are determined assuming animals are field cage reared, and are average for other personality measures, as well as number of relocations, and time on project.

Figure 4:

Interaction between temperament and relocations on expected count of diarrhea over 2 years based on the fitted model in Table 4: Model was fit using only monkeys that had at least one occurrence of diarrhea. Each plots includes three curves representing the expected count of diarrhea with low, average, or high values of the respective temperament. Low and high temperament score are calculated as one standard deviation below or above average temperament of the population. The vertical lines indicate the average number of relocations in the study population (4.88 relocations). Expected counts are determined assuming animals are field cage reared, and are average for other personality measures and time on project.

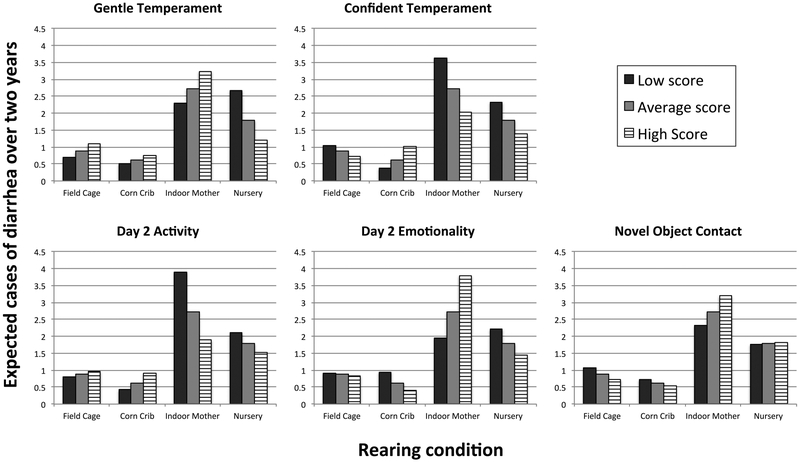

The main effect of indoor mother rearing approached significance (P = 0.06), with the expected count of repeat diarrhea for indoor mother reared animals with average temperament measures 75% higher than for field cage reared monkeys. The effect of indoor mother rearing was significantly impacted by temperament: indoor mother reared animals that were expected to have most numerous repeat diarrhea were low on Day 2 Activity (P < 0.05), high on Day 2 Emotionality (P < 0.05), and/or high on Novel Object contact (P < 0.01). Finally, among nursery-reared animals, more frequent repeat bouts were seen for animals low on Gentle temperament (P < 0.001), while among corn crib-reared animals, more frequent bouts were seen among animals high in Confidence (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Interaction between temperament and rearing condition for expected count of diarrhea over 2 years based on fitted model in Table 4: Model was fit using only monkeys that had at least one occurrence of diarrhea. Each plots represents the expected count of diarrhea with low, average, or high values of the respective temperament. Low and high temperament score are calculated as one standard deviation below or above average temperament of the study population. Expected counts are determined assuming animals are average for other personality measures, as well as number of relocations, and time on project.

DISCUSSION

To evaluate the effects of personality and environment on the occurrence of diarrhea within the first three years of life in captive rhesus macaques we evaluated two models: diarrhea risk (an animal’s risk for having diarrhea at least once) and chronic diarrhea (how many repeated bouts of diarrhea an animal is expected to have after their initial bout). We hypothesized that individual personality, rearing environment and relocations would all predict chronic diarrhea in rhesus macaques, but that the relative impact of rearing environment and relocations would be highly dependent on an individual’s personality. Similar to the human literature we found that certain personality types (e.g., nervous, timid, and not confident) were more likely to have chronic diarrhea, and that certain stressful environments (e.g., frequent relocations) increased diarrhea risk. Perhaps most importantly, we found significant interactions between management practices, such as rearing environment and housing relocations, and temperament. This supports our hypotheses, and suggests that management practices do not impact all animals equally. Rather, the relative impact of colony management practices on diarrhea risk, and chronic diarrhea, is dependent on individual personality.

Model 1: Diarrhea Risk

Diarrhea risk and relocations

As expected, the more times an average animal was relocated during the study period the higher their risk for having diarrhea. As previously noted, this does not include relocations into or out of a hospital, therefore this relationship was not simply an artifact of sick animals relocating into the hospital for medical care. Rather, these results demonstrate that relocating an animal, an event known to be stressful for captive primates, generally increases their relative risk for diarrhea. This relationship is similar to that found in humans, in which stressful life events increase individual risk for gastrointestinal disorders and associated bouts of chronic diarrhea (For reviews see Maunder, 2005; Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005). Of course, the effect of more relocations on diarrhea risk might be the result of greater exposure to pathogens; while we cannot rule out this possibility, cage sanitation practices and our facility’s experience that different parts of the facility generally to do not show different prevalences of relevant pathogens might argue against such an interpretation. We recognize that more data would help distinguish between these interpretations.

Interestingly, although all four temperament scores (Vigilant, Gentle, Confident, and Nervous) were included in the final model for diarrhea risk, none of the measures were statistically significant on their own. There were, however, significant interactions between all four temperament scores and the number of times an animal was relocated. As suggested in Figure 1, temperament scores did not significantly predict risk of diarrhea for monkeys with an average number of relocations (4.22). Rather, temperament score only predicted diarrhea risk when monkeys were more frequently relocated (a relatively “stressful” experience); a much smaller effect of temperament was seen among animals that were rarely relocated (a relatively “low stress” experience). These results support the “interactionist” perspective on personality and health, in which personality is only expected to influence disease when combined with other factors such as stress and environment (Eysenck, 1991).

To understand the relationship between personality, risk of diarrhea, and relocations, it is important to recognize that characteristics of specific personality types can be evolutionarily beneficial in one environment, and yet maladaptive and harmful in another (Sih, Bell, & Johnson, 2004; Sih, Bell, Johnson, & Ziemba, 2004; Weinstein, Capitanio, & Gosling, 2008). For example, animals with a “proactive” personality type tend to thrive in stable environments, while those with “reactive” personalities are often better adapted to unstable, changing environments. Proactive animals are typically aggressive, bold, and attempt to manipulate or control their environment (Sih, Bell, & Johnson, 2004; Sih, Bell, Johnson, et al., 2004); these traits are beneficial in relatively constant environments, yet can hinder one’s ability to adjust to changing conditions (Sih, Bell, & Johnson, 2004; Sih, Bell, Johnson, et al., 2004). In contrast, reactive animals are typically cautious, highly attentive to external stimuli, and respond passively to their environments, making them relatively adapted to changing environmental conditions (Sih, Bell, & Johnson, 2004; Sih, Bell, Johnson, et al., 2004). In the current study, monkeys were overall most likely to have diarrhea in a relatively unstable environment (i.e., frequent relocations). Under those conditions, however, individuals with the least risk for diarrhea were those that were high on the temperament scales for nervous (nervous, fearful, timid, not calm, not confident), gentle (gentle, calm, flexible, curious), and/or vigilant (vigilant, not depressed, not tense, timid) (although it should be noted that the interaction between vigilant and relocations only approached statistical significance at P = 0.07). Similar to reactive temperaments, these temperaments traits appear to benefit monkeys in unpredictable, frequently changing environments. In contrast, animals with high values for Confident were at greatest risk in these “unstable” environments. Much like proactive individuals, confident monkeys may best thrive in relatively constant environments. Finally, as Figure 1 indicates, when housed in a relatively stable environment (i.e., few relocations), the effect of temperament on the odds of diarrhea was small.

Diarrhea risk and rearing history

Surprisingly, we found no significant main effects of rearing history on risk of diarrhea. Previous research found diarrhea to be lowest in outdoor reared monkeys, and highest in indoor or nursery raised individuals. Of outdoor-housed animals, large social groups (equivalent to the field cage animals in our study) have been shown to have less diarrhea than smaller social groups (equivalent to corn cribs animals in our study) (Prongay et al., 2013). While our final model did not include significant main effects of rearing history, it is of note that the trend of diarrhea risk was similar to all previous published reports; in our data (Table 3), diarrhea was lowest in outdoor-reared animals (field cage and corncrib) and highest for indoor-reared animals (indoor mother-, and nursery-reared).

The model resulted in only one significant interaction between temperament and rearing; nervous temperament score positively predicted diarrhea risk in nursery reared animals with an average number of relocations (Figure 2), a result that we reported elsewhere (Elfenbein et al., 2016). Previous research has demonstrated nursery rearing to lead to a suite of behavioral and physiological changes, including abnormal regulation of the HPA axis (e.g., John P. Capitanio, Mason, Mendoza, DelRosso, & Roberts, 2006), increased emotionality (e.g., Gottlieb & Capitanio, 2013), and increased risk of pathological behaviors (e.g., Rommeck et al., 2009). Our result suggests that the abilities of nursery-reared animals to cope with everyday events may be particularly limited for those with a Nervous temperament.

Model 2: Chronic Diarrhea

Diarrhea count and temperament

Unlike the model of diarrhea risk, the model of chronic diarrhea demonstrated significant main effects of the temperament measures Vigilant, Gentle, Confident, Nervous, and Novel Object Contact. While not directly comparable (due to differences in age and temperament measures utilized), these result are supportive of Howell and colleagues (2012), who similarly found main effects of personality measures in adult rhesus macaques on risk of chronic idiopathic colitis. Although there are additional interactions that complicate the picture, our results demonstrate that once an individual had its first bout of diarrhea, the “average” monkey (i.e., field cage reared with average number of relocations) was expected to have more bouts of diarrhea if they were high on the temperament measures Nervous (nervous, fearful, timid, not calm, not confident), Gentle (gentle, calm, flexible, curious), and/or Vigilant (vigilant, not depressed, not tense, timid) and low on the measures Confident (confident, bold, active, curious, playful) and/or Novel Object Contact (a behavioral test frequently used as a measure of boldness and confidence) (Figure 3). In the human literature, people are at greater risk for gastrointestinal disorders if they are neurotic, introverted, nervous, and/or anxious. Although our measures of temperament in rhesus macaques are not completely analogous to these human measures (though see Capitanio, Mendoza, & Cole, 2011), it is notable that similar to humans, rhesus macaques were at higher risk for chronic diarrhea if they were nervous, timid, and not confident.

Diarrhea count and relocations

Unlike the first model, there was no significant main effect of relocations alone on expected counts of diarrhea. There were, however, many significant interactions in the second model between relocations and personality measures. As suggested in Figure 4, number of relocations did not significantly predict expected count of diarrhea in monkeys with average measures of Confidence, Day 2 Activity, and Novel Object Contact. In contrast, animals that were particularly high or low on either of these three personality measures were strongly affected by relocations, once again supporting the interactionist perspective on personality and health. Thus it appears that while frequent relocations put all personality types at higher risk for a single bout of diarrhea, the long term health effects of frequent relocations (i.e., chronic diarrhea or health recovery) was largely dependent on an animals’ personality.

Diarrhea count and rearing history

Similar to Model 1, we found no significant main effects of rearing history on diarrhea count. However, much like the model of diarrhea risk, the data demonstrate a clear pattern of higher expected count of recurring diarrhea episodes in indoor raised monkeys (nursery and indoor mother reared) compared to outdoor raised monkeys (corn crib and field cage) (Figure 5), consistent with previously published reports (Hird et al., 1984).

We found multiple significant interactions between rearing and personality measures, exposing relationships between temperament and chronic diarrhea that are unique for each rearing environment at the CNPRC. These results are particularly difficult to interpret; previous research has demonstrated an animal’s rearing condition can significantly influence their personality (John P. Capitanio et al., 2006; Gottlieb & Capitanio, 2013). Still, the results reported here are informative in demonstrating the predictive nature of various personality types given an animals rearing environment. Below we discuss and speculate on the causality of these interactions, however we recognize that further research is needed to truly determine why specific temperaments lead to increased risk of chronic diarrhea in some, but not all rearing environments.

Corn crib rearing.

Corn crib reared animals that had diarrhea once were expected to have increased bouts of diarrhea if they were high on the personality measure Confident (Figure 5). Like field cage reared animals, corn crib reared animals are raised in social groups. Unlike field cages, however, corn cribs are relatively small (15–30 individuals) with limited physical space (400 sq. feet). Previous research has demonstrated relatively higher rates of aggression and injury in socially housed rhesus macaques caged in smaller housing environments, compared to large field cage like housing (Prongay, personal communication). Assuming similar social dynamics were operating in our facility it would appear that overly confident animals may have an increased health risk in this environment.

Nursery rearing.

Nursery reared animals that had diarrhea once were expected to have increased bouts of diarrhea if they were low on Gentle temperament, which involves having been rated low for the individual traits of gentle, calm, flexible, and curious (Figure 5). Elsewhere, we have argued that low values for Gentle temperament reflect a tendency toward an active style of responding – such animals are at higher risk for developing motor stereotypy, for example (Gottlieb et al., 2013). Beyond just greater activity, however, a low value for Gentle suggests that activity may be somewhat agitated – such animals were rated less calm, less flexible. It may be that this more agitated/active style of behavior, when combined with early social restriction, results in a poor outcome when individuals are put into social groups later in their first year of life, such as happens at our facility. It would be instructive to have quantified behavioral data on how such individuals fare in such a situation.

Indoor mother rearing.

Indoor mother reared animals showed the most unique relationships between personality and chronic diarrhea. Unlike other monkeys, indoor mother reared subjects with average relocations that had diarrhea once were expected to have increased bouts of diarrhea if they were low on Day 2 Activity, high on Day 2 Emotionality, and high on Novel Object Contact (Figure 5). As described above, the common response to participating in the BBA program is to increase activity (locomotion, eating) on Day 2 and to decrease affective responding (coo, bark, lipsmack) on Day 2, a pattern that we believe reflects good adaptation to the BBA situation. Consistent with this idea, our results indicate that indoor mother reared animals that show this pattern of good adaptation are expected to have less bouts of diarrhea compared to indoor mother reared animals that show poor adaptation during BBA. The relative inactivity of the animals low on Day 2 Activity may have kept them in proximity to the novel object, resulting in higher scores for manipulation of the object. We recognize that this interpretation is speculative, and again acknowledge that behavioral data on such animals in their social groupings would be very useful to confirm our suggestion.

As the human literature suggests, we found that stressful experiences, specifically animal relocations, increased risk for experiencing at least one bout of diarrhea. Also similar to humans, we found that nervous, and not confident monkeys were at highest risk for chronic diarrhea. Interestingly, however, there were strong interactions between personality and environment, where the relative impact of these stressful environments was highly dependent on an animal’s personality. These results can be used to help identify high-risk individuals, and to inform selection of animals for various research projects or housing environments. For example, it is widely agreed that indoor rearing is more stressful and less desirable for rhesus macaque wellbeing than social group rearing. While our models found trends of both higher risk, and higher rates of diarrhea in indoor reared macaques, these relationships were magnified for animals that were nervous, agitated, or showed poor adaptation during BBA. From a practical standpoint, these individuals are at highest risk, and in order to catch and treat the problem in the early stages should be closely monitored for signs of diarrhea. Further, these animals should be avoided when selecting subjects for research projects in which diarrhea may be a confounding factor. This example highlights the fact that not all stressful environments increase risk of diarrhea and chronic diarrhea equally in all individuals. Rather, it is the individuals that presumably perceive these environments as stressful, or have personalities less ideally suited for these environments, that are at highest risk for diarrhea

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Center for Research Resources (R24RR019970 to J.P.C. and P51RR000169 to CNPRC) and is currently supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/OD (R24OD010962 and P51OD011157, respectively). The authors thank Laura Calonder for technical assistance with the BBA program, and the CNPRC animal care and veterinary staffs for support.

REFERENCES

- Akaike H (1987). Factor-analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. doi: 10.1007/bf02294359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MT, & Coe CL (1999). Maternal separation disrupts the integrity of the intestinal microflora in infant rhesus monkeys. Developmental Psychobiology, 35(2), 146–155. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E, Tennant C, Piesse C, Badcock C, & Kellow J (1998). Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut, 43(2), 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitton A, Sewitch MJ, Peppercorn MA, Edwardes MDD, & Shah S (2003). Psychosocial determinants of relapse in ulcerative colitis: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 98(10), 2203–2208. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(03)00750-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP (2011). Nonhuman primate personality and immunity: Mechanisms of health and disease Personality and Temperament in Nonhuman Primates (pp. 233–255): Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP (2017). Variation in BioBehavioral Organization. Handbook of Primate Behavioral Management, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Abel K, Mendoza SP, Blozis SA, McChesney MB, Cole SW, & Mason WA (2008). Personality and serotonin transporter genotype interact with social context to affect immunity and viral set-point in simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 22(5), 676–689. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, & Lerche NW (1998). Social separation, housing relocation, and survival in simian AIDS: A retrospective analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(3), 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mason WA, Mendoza SP, DelRosso L, & Roberts JA (2006). Nursery Rearing and Biobehavioral Organzation In Sackett GP, Ruppenthal GC & Elias K (Eds.), Nursery Rearing of Nonhuman Primates in the 21st Century (pp. 191–214). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, & Baroncelli S (1999). The relationship of personality dimensions in adult male rhesus macaques to progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 13(2), 138–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, & Bentson KL (2004). Personality characteristics and basal cortisol concentrations in adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(10), 1300–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, & Cole SW (2011). Nervous temperament in infant monkeys is associated with reduced sensitivity of leukocytes to cortisol’s influence on trafficking. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 25(1), 151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K (2012). Individual differences in temperament and behavioral management practices for nonhuman primates. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 137(3–4), 106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SM (2001). IV. Modulation of intestinal inflammation by stress: basic mechanisms and clinical relevance. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 280(3), G315–G318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SM, McHugh K, Jacobson K, Khan I, Riddell R, Murase K, & Weingarten HP (1996). Previous inflammation alters the response of the rat colon to stress. Gastroenterology, 111(6), 1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett CM, Bowers CL, Sackett GP, & Bowden DM (1993). Urinary cortisol responses of longtailed macaques to 5 cage sizes, tethering, sedation, and room change. American Journal of Primatology, 30(1), 55–74. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350300105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett CM, Bowers CL, Shimoji M, Leu M, Bowden DM, & Sackett GP (1995). Behavioral-responses of longtailed macaques to different cage sizes and common laboratory experiences. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 109(4), 368–383. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.109.4.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy LC, Zielezny MA, Marshall JR, Byers TE, Weiser MM, Phillips JF, … Graham S (1991). Relevance of major stress events as an indicator of disease-activity prevalence in inflammatory bowel-disease. Behavioral Medicine, 17(3), 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein HA, Rosso LD, McCowan B, & Capitanio JP (2016). Effect of indoor compared with outdoor location during gestation on the incidence of diarrhea in indoor-reared rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 55(3), 277–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore DB, Anderson JH, Hird DW, Sanders KD, & Lerche NW (1992). Diarrhea Rates and Risk Factors for Developing Chronic Diarrhea in Infant and Juvenile Rhesus Monkeys. Laboratory Animal Science, 42(4), 356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ (1991). Personality, stress, and disease: An interactionist perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 2(3), 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, & Pavan L (1977). Large bowel disorders .1. Illness configuration and life events. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 27(2), 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack J, & de Waal F (2004). Dominance style, social power, and conflict In Thierry B, Singh M& Kaumanns W(Eds.), Macaque Societies: A Model for the Study of Social Organization (pp. 157–185). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HD, & Gosling SD (2010). Personality in nonhuman primates: a review and evaluation of past research. American Journal of Primatology, 72(8), 653–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett VD, Brantley PJ, Jones GN, & McKnight GT (1991). The relation between daily stress and crohns-disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14(1), 87–96. doi: 10.1007/bf00844770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub MS, Hogrefe CE, Widaman KF, & Capitanio JP (2009). Iron Deficiency Anemia and Affective Response in Rhesus Monkey Infants. Developmental Psychobiology, 51(1), 47–59. doi: 10.1002/dev.20345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DH, & Capitanio JP (2013). Latent Variables Affecting Behavioral Response to the Human Intruder Test in Infant Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta). American Journal of Primatology, 75(4), 314–323. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DH, Capitanio JP, & McCowan B (2013). Risk factors for stereotypic behavior and self-biting in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta); animal’s history, current environment, and personality. American Journal of Primatology, 75(10), 995–1008. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene BR, Blanchard EB, & Wan CK (1994). Long-term monitoring of psychosocial stress and symptomatology in inflammatory bowel-disease. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32(2), 217–226. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90114-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gue M, Bonbonne C, Fioramonti J, More J, DelRioLacheze C, Comera C, & Bueno L (1997). Stress-induced enhancement of colitis in rats: CRF and arginine vasopressin are not involved. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 272(1), G84–G91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A, & Kamm M (2002). Mechanisms of initiation and perpetuation of gut inflammation by stress. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 16(12), 2017–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hird DW, Anderson JH, & Bielitzki JT (1984). Diarrhea in nonhuman-primates - a survey of primate colonies for incidence rates and clinical opinion. Laboratory Animal Science, 34(5), 465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg CA, Leininger R, Wheeldon E, Slater D, Henrickson R, & Anderson J (1982). Clinicopathological Studies of Gastrointestinal Disease in Macaques. Veterinary Pathology Online, 19(7 suppl), 163–170. doi: 10.1177/030098588201907s12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell S, White D, Ingram S, Jackson R, Larin J, Morales P, … Wagner J (2012). A bio-behavioral study of chronic idiopathic colitis in the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 137(3), 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Andreoli A, Luzi C, … Marcheggiano A (2000). Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: A prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95(5), 1213–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C, & Andreoli A (1993). Development of the perceived stress questionnaire - a new tool for psychosomatic research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 37(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Line SW, Markowitz H, Morgan KN, & Strong S (1991). Effects of cage size and environmental enrichment on behavioral and physiological responses of rhesus macaques to the stress of daily events In Novak M & Petto AJ (Eds.), Through the looking glass: Issues of psychological wellbeing in captive nonhuman primates (pp. 160–179). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG (2005). Evidence that stress contributes to inflammatory bowel disease: evaluation, synthesis, and future directions. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 11(6), 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley JE, & Rampton DS (2005). Psychological stress in IBD: New insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut, 54(10), 1481–1491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Kegney FP, Gordon RO, & Levine SM (1970). A psychosomatic comparison of patients with ulcerative colitis and crohns disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 32(2), 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G, & Gomber J (1976). Moving laboratory rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) to unfamiliar home cages. Primates, 17(4), 543–546. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Zanzi CA, Thurmond MC, Hird DW, & Lerche NW (1999). Effect of weaning time and associated management practices on postweaning chronic diarrhea in captive rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Laboratory Animal Science, 49(6), 617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA (2003). Self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys: New insights into its etiology, physiology, and treatment. American Journal of Primatology, 59(1), 3–19. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Meyer JS, Lutz C, & Tiefenbacher S (2006). Deprived Environments: Developmental Insights from Primatology In Mason G & Rushen J (Eds.), Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare (2nd ed., pp. 153–189). Wallingford: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix CH, & Chambers KC (1984). Sexual-behavior and serum hormone levels in aging rhesus males - effects of environmental-change. Hormones and Behavior, 18(2), 206–215. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(84)90043-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prongay K, Park B, & Murphy SJ (2013). Risk Factor Analysis May Provide Clues to Diarrhea Prevention in Outdoor‐Housed Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta). American Journal of Primatology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu BS, Vallance BA, Blennerhassett PA, & Collins SM (1999). The role of CD4(+) lymphocytes in the susceptibility of mice to stress-induced reactivation of experimental colitis. Nature Medicine, 5(10), 1178–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSC, Hatfield RA, Suls JM, & Chamberlain MJ (1998). Psychological and physical stress induce differential effects on human colonic motility. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 93(6), 985–990. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(98)00174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DAF, Ray J, Diamond I, & Edwards JG (1989). Personality profile and affective state of patients with inflammatory bowel-disease. Gut, 30(5), 623–626. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.5.623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommeck I, Anderson K, Heagerty A, Cameron A, & McCowan B (2009). Risk Factors and Remediation of Self-Injurious and Self-Abuse Behavior in Rhesus Macaques. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 12(1), 61–72. doi: Doi 10.1080/10888700802536798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RG, Rosenkranz SL, Lee LA, Howard H, Digiacomo RF, Bronsdon MA, … Morton WR (1987). Epidemiology and etiology of diarrhea in colony-born macaca-nemestrina. Laboratory Animal Science, 37(3), 309–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, & Munck AU (2000). How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocrine Reviews, 21(1), 55–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestak K, Merritt CK, Borda J, Saylor E, Schwamberger SR, Cogswell F, … Lackner AA (2003). Infectious agent and immune response characteristics of chronic enterocolitis in captive rhesus macaques. Infection and Immunity, 71(7), 4079–4086. doi: 10.1128/iai.71.7.4079-4086.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sih A, Bell A, & Johnson JC (2004). Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19(7), 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sih A, Bell AM, Johnson JC, & Ziemba RE (2004). Behavioral syndromes: an integrative overview. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 79(3), 241–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Tarara RP, & Cole SW (2008). Social temperament and lymph node innervation. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 22(5), 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanum L, & Malt UF (2001). Personality and physical symptoms in nonpsychiatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 50(3), 139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchi A, Lepre L, Liotta G, Mazzoni G, Costa G, Taborra L, & Miccini M (1997). Familial and psychological risk factors of ulcerative colitis. Italian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 29(5), 395–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA 1991. Animal welfare, standards, final rule (part 3, subpart d: Specifications for the humane handling, care, treatment, and transportation of nonhuman primates).

- Weinstein TA, Capitanio JP, & Gosling SD (2008). Personality in animals. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 3, 328–348. [Google Scholar]

- Whybrow PC, Kane FJ, & Lipton MA (1968). Regional ileitis and psychiatric disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 30(2), 209–&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk JL, Maginnis GM, Coleman K, Lewis A, & Ogden B (2008). Evaluation of the use of coconut to treat chronic diarrhea in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Medical Primatology, 37(6), 271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]