Abstract

Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus is sensitive to endogenous and exogenous factors that influence hippocampal function. Ongoing neurogenesis and the integration of these new neurons throughout life thus may provide a sensitive indicator of environmental stress. We examined the effects of Aroclor 1254 (A1254), a mixture of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), on the development and function of newly generated dentate granule cells. Early exposure to A1254 has been associated with learning impairment in children, suggesting potential impact on the development of hippocampus and/or cortical circuits. Oral A1254 (from the 6th day of gestation to postnatal day 21) produced the expected increase in PCB levels in brain at postnatal day 21, which persisted at lower levels into adulthood. A1254 did not affect the proliferation or survival of newborn neurons in immature animals nor did it cause overt changes in neuronal morphology. However, A1254 occluded the normal developmental increase in sEPSC frequency in the third post-mitotic week without altering the average sEPSC amplitude. Our results suggest that early exposure to PCBs can disrupt excitatory synaptic function during a period of active synaptogenesis, and thus could contribute to the cognitive effects noted in children exposed to PCBs.

Keywords: critical period, hippocampus, neurogenesis, PCBs, synapse formation

Introduction

Hippocampal neurogenesis occurs during early development and persists throughout adulthood. Newborn neurons that survive extend dendrites and receive functional input from the existing circuits as early as 2 weeks after birth in rodents (Overstreet-Wadiche & Westbrook, 2006). Those surviving newborn granule cells have important roles in learning and spatial memory (Deng et al., 2010), and are regulated by many factors such as sex steroids and thyroid hormones (Bernal, 2007; Galea, 2008; Parent et al., 2011). Thus, this relatively homogenous cell population provides a sensitive endpoint in a developmental window when endogenous and exogenous factors affect neural circuits. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a group of 209 congeners used in lubricating oils and plasticizers (Gore et al., 2015), have been banned since the 1970s, but because of their long half life, they are still ubiquitous in the environment (Chu et al., 2003). It has been known for several decades that early exposure to PCBs during gestation or lactation is associated with subsequent learning and memory impairment in children as well as animals (Jacobson et al., 1990; Jacobson & Jacobson, 1996; Patandin et al., 1999; Gilbert et al., 2000; Roegge et al., 2000; Widholm et al., 2001), suggesting that these environmental chemicals alter the function of neuronal circuits.

Although PCB production is now forbidden, these toxicants persist in the environment as indicated by recent human exposure studies (Eubig et al., 2010; Fång et al., 2013) and negative effects on cognitive function are still being identified (Vreugdenhil et al., 2002; Stewart et al., 2008). Such effects have been observed in both humans and animals. Prenatal exposure has been associated with lower full-scale, verbal intelligence quotient and memory performances in young children in Michigan (Jacobson et al., 1990; Jacobson & Jacobson, 1996) and in the Netherlands (Patandin et al., 1999). In rodents, exposure in utero and during lactation to 6 mg/kg/day of A1254 led to spatial memory deficits (Roegge et al., 2000; Widholm et al., 2001). However, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. We used transgenic mice and viral vectors to specifically label newborn granule cells and determine the effects of perinatal exposure to Aroclor 1254 (A1254) on synapses and neural circuits in the hippocampus.

Materials and methods

Animal and exposure

All animal procedures on C57BL/6J mice were approved by the appropriate committees at the University of Liège and the Oregon Health and Science University and in accord with the NIH guidelines for handling of animals. Wild-type (JAX) and POMC-EGFP (proopiomelanocortin – enhanced green fluorescent protein) transgenic mice (Overstreet et al., 2004) were exposed to PCBs either through placenta and maternal milk or during adulthood. Dams were orally exposed daily to either A1254 (AccuStandard, Inc., New Haven, CT; 6 mg/kg/day) or vehicle (corn oil), injected in one-ninth of a wafer (Delacre, Groot-Bijgaarden, Belgium), from embryonic day 6 (E6) and continuing to postnatal day 21 (P21). When exposed during adulthood, mice received a wafer with either A1254 (6 mg/kg/day) or vehicle (corn oil), daily from postnatal week 10 to postnatal week 12 or 15. The doses were adjusted to account for change in body weight of the dams or adults. Experimental groups contained males and females born from at least three different dams.

PCBs levels in brain

To evaluate exposure to A1254, the five most abundant PCBs congeners (PCB 101, 118, 138, 153, and 180) were measured in the brain of mice. PCB congeners were analyzed in the brain using gas chromatography coupled to 63ECD and to mass spectrometry modified from Debier et al. (2003; See Data S2).

T4 serum concentration

Free thyroxin was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (Beckman Coulter IM1363 Brea, CA, USA). The limit of detection was 1.86 pg/mL. When the level of free thyroxin was below that limit, it was assigned the value at the limit of detection (5–8 animals per group). The total thyroxin concentration at P21 and P56 was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (MP biomedical 06B254011, Solon, OH, USA). The detection limit was 20 ng/mL. At P7 and after adult exposure, total thyroxin was measured using a homemade radioimmunoassay adapted from Gauger et al. (2004). Using this method the limit of detection was 1 ng/mL (10–23 animals per group in immature animals, 6 animals per group in adults).

Stereotaxic injection

To label newborn granule cells, a replication-deficient Moloney murine leukemia virus-based retroviral vector (Lewis & Emerman, 1994; Luikart et al., 2012) was injected stereotaxically into the dorsal hippocampus of wild-type C57BL/6J mice. The injections were performed at P7 for electrophysiological and dendritic length analysis, and at P7 and P56 for spine density and spine morphology analysis. Mice were anesthetized in an induction chamber using isoflurane gas system (Veterinary Anesthesia Systems Co.) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame. At P7, the coordinates were as follows: x: ±1.5 mm, y: ±1.6 mm from Lambda. Using a 10-μL Hamilton syringe fitted with a 30-gauge needle and the Quintessential stereotaxic Injector (Stoelting), 0.5 μL of virus was delivered at 0.25 μL/min at z-depths of 2.4 and 2.2 mm. In adults, the coordinates were as follows: x: ±1.1 mm, y: −1.9 mm from Bregma. One μL of virus was injected at z-depths of 2.5 and 2.3 mm. Animals received post-operative lidocaine and drinking water containing Children’s Tylenol. Viral particles were prepared using established protocols with titers of 1–10 × 106 (Luikart et al., 2011).

BrdU administration

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma, St Louis, MO) was administered intra-peritoneally in wild-type mice at P7 (50 mg/kg/injection, 3 injections, 2 h apart) or P56 (100 mg/kg/injection, 3 injections, 2 h apart). BrdU was also administered at 12 weeks postnatal (100 mg/kg/injection, 3 injections, 2 h apart) after adult exposure to A1254.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were deeply anesthetized with Nembutal (Ceva Sante Animale, Bruxelles, Belgium; Liège) or 2% Avertin (2,2,2-Tribromoethanol, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; OHSU), then transcardially perfused with PBS/4% sucrose followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/4% sucrose. Tissue processing and immunostaining were as described previously (Luikart et al., 2011). Coronal sections (30–100 μm) were cut using a VT-1000S (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). The primary antibodies were as follows: BrdU (1 : 200; AbD Serotech, Dusseldorf, Germany), NeuN (1 : 500; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), Olig2 (1 : 200; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), GFAP (1 : 2000; Dako, Carpinteria, USA), and GFP (1 : 500; Life Technologies, Eugene, USA). The secondary antibodies (1 : 300) were as follows: BrdU: rhodamine donkey anti-rat (Jackson ImmunoResearch laboratories, West Grove, USA); NeuN: Alexa fluor 488 Donkey anti-mouse (Life Technologies, Gent, Belgium); Olig2 and GFAP: Alexa Fluor 647 Goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Eugene, USA); and GFP: Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-chicken (Life Technologies, Eugene, USA).

Imaging, morphological, and PCR analysis

All imaging and quantifications were done blinded. For BrdU analysis, image z-stacks (three images, 4 μm apart) were obtained using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope with a 20× objective. The positive cells were counted in 10 sections along the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. The cell survival ratio is the number of BrdU+ cells 3 weeks after BrdU injections divided by the number of BrdU+ cells 1 h after the last injection of BrdU multiplied by 100. Three to eight animals were used per age and condition. For quantifying the number of newborn granule cells in POMC-EGFP animals, image z-stacks were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 780 laser-scanning confocal microscope. We counted the number of granule neurons expressing EGFP from anatomically equivalent sections of the suprapyramidal blade of the dorsal portion of the dentate gyrus (six adjacent sections per animal) in P7, P14, and P21 animals or from the whole dentate gyrus in adults (5–8 animals per age and group). Dentric arborization, dendritic spine density, and morphology were assessed as described previously (Luikart et al., 2011; Perederiy et al., 2013). Details can be found in Data S2.

Fluorescent activated cell sorting and real-time PCR techniques are described in the Data S2.

Electrophysiology

Newborn neurons were labeled by retroviral injection at P7. Brain slices were prepared from the dentate gyrus of control and A1254-treated animals at P21, P28, and P42 as previously described (Perederiy et al., 2013). Whole-cell recordings were made in labeled newborn neurons and in adult neurons at P42 in voltage clamp at a holding potential of −70 mV. The internal solution contained (in mM): 113 CsGluconate, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 17.5 CsCl, 8 NaCl, 2 MgATP, and 0.3 NaGTP (pH: 7.3, adjusted with CsOH; 290 mOsm). To examine spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents (sEPSCs), the bath contained (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, and the GABAA antagonist SR29931 (10 μm), and bubbled with 95%O2/5% CO2. sEPSCs were collected over a 10 min epoch, digitized at 10 kHz, and analyzed using axograph software (Axograph Scientific, Australia). The detection template for sEPSCs was as follows: 10 ms baseline, 1 ms rise time, 6 ms decay, —25 pA peak amplitude, and 30 ms duration. Records were manually inspected and events with < 50 μs rise time or < 4 pA peak amplitude (< 2× baseline RMS noise) were rejected. The recordings were done blinded to condition.

Statistical analysis

We used unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests or two-way anova (Statistica 10.0 Statsoft Inc) as appropriate. The F-test was used for testing the equality of variances in sEPSC experiments. Data are generally reported as mean + SEM, and all experiments were analyzed after blinding. Sample sizes were chosen based on similar experiments to detect changes of > 20% with a variance of 20% of mean, and power = 0.8. Depending on the experiment, sample sizes ranged from 5 to 20.

Results

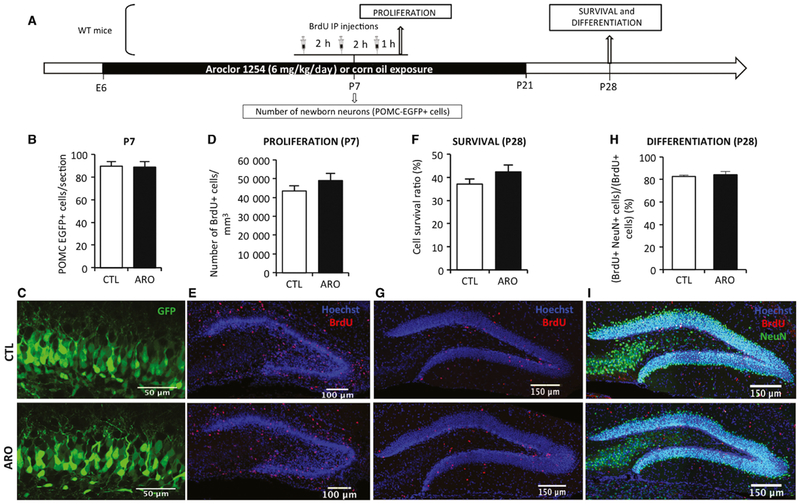

Perinatal exposure to PCBs did not alter proliferation or survival of newborn granule cells in young animals (P7–21)

As expected, perinatal exposure to A1254 led to PCB accumulation in the brain and transient decrease in total and free thyroxin serum concentration (Data S1 and Fig. S1). We used a novel experimental approach to determine the effects of perinatal exposure to Aroclor 1254 (A1254), a PCB mixture, on synapses and neural circuits in the mouse hippocampus. We identified newborn granule cells using proopiomelanocortin-enhanced GFP (POMC-EGFP) transgenic mice in which newborn granule cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) transiently and specifically express enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) during the first weeks after cell birth (Overstreet et al., 2004). We also used stereotaxic injections of retroviruses expressing EGFP to track the dendritic and synaptic development of newly generated granule cells. Using POMC-EGFP transgenic mice, exposure to A1254 did not modify the number of newborn neurons at P7 (T = 0.13, P = 0.9; Fig. 1B and C). Similarly, the number of newborn neurons at P14 and P21 was not significantly different in control and exposed mice (P14, CTL: 67 ± 4 POMC-EGFP+ cells/section, n = 5; ARO: 59 ± 5.4 POMC-EGFP+ cells/section, n = 5, T = −0.02, P = 0.9; P21, CTL: 65 ± 2 POMC-EGFP+ cells/section, n = 5; ARO: 70 ± 1 POMC-EGFP+ cells/section, n = 5; T = −2.07, P = 0.1). The number of proliferating or surviving cells labeled with BrdU was unchanged after perinatal exposure to A1254 (Fig. 1D–G), consistent with the results in POMC-EGFP mice. The proportion of newborn neurons that had differentiated (BrdU+ NeuN+/BrdU+) 3 weeks after BrdU injections was not affected by A1254 (T = −0.45, P = 0.2; Fig. 1H and I). Thus, despite high brain levels of A1254 and reduced thyroxin serum levels, proliferation, survival, or differentiation was not affected during this robust period of neurogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Perinatal exposure to A1254 did not affect proliferation and survival at the time of weaning. (A) Experimental timeline. Mice were exposed to PCBs from E6 to P21. The number of POMC-EGFP-positive cells was counted at P7. Bromodeoxyuridine was injected at P7 (3 injections, 2 h apart) and BrdU-positive cells were counted 1 h (proliferation) or 3 weeks (survival) after the last BrdU injection in wild-type (WT) mice. (B and C) Number of newborn neurons (POMC-EGFP-positive cells, in green) at P7. (D and E) Number of cells in S-phase of the cell cycle (BrdU, in red) in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus in control (CTL) and exposed mice (AR0). (F and G) Cell survival ratio at P28 (H and I) Percentage of differentiated neuron 3 weeks after BrdU injections (red: BrdU, green: neuronal marker NeuN, blue: Hoescht). Data are mean ± SEM. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

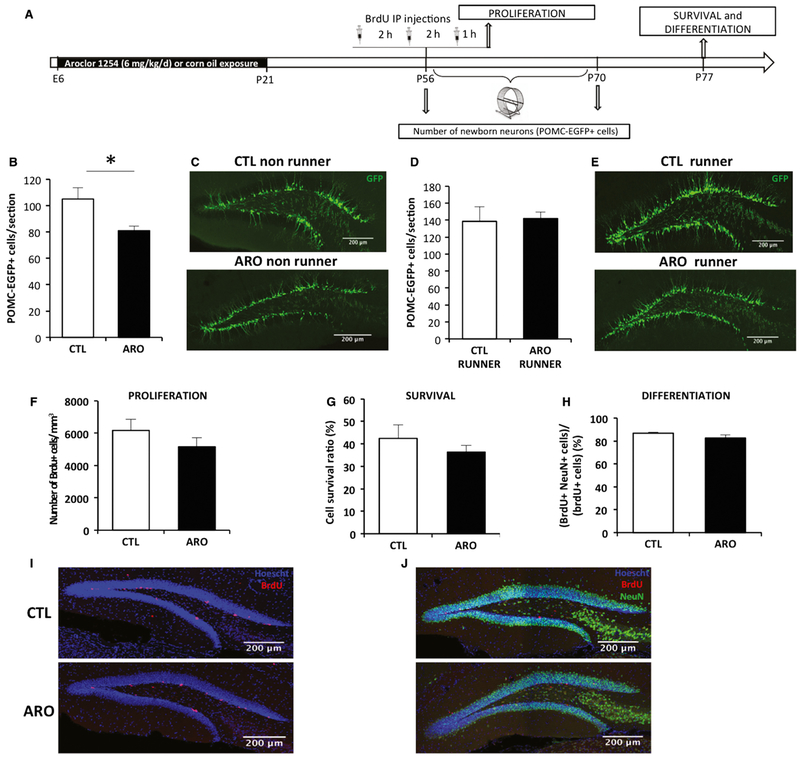

Perinatal exposure to PCB modestly reduced the number of newborn granule cells in adult animals

Perinatal exposure to A1254 led to a modest decrease in POMC-EGFP+ cells in adult mice (T = 2.75, P = 0.01; Fig. 2B and C), suggesting that proliferation or survival may be more vulnerable to the lingering effects of PCBs in the period from P42 to P56. For BrdU injected at P56, however, we did not detect a change in proliferation (T = 1.13, P = 0.3; Fig. 2F and I), cell survival (T = 0.77, P = 0.4; Fig. 2G and J), or differentiation (T = 1.89, P = 0.08; Fig. 2H and J). Although there was a trend toward a decrease in proliferation and survival, an analysis of the total number of BrdU+ cells at P77 did not show a significant decline (CTL: 2618 ± 362; ARO: 1874 ± 163, P = 0.15). This apparent discrepancy likely reflects the decreasing levels of A1254 from P56 to P77. In other words, BrdU in our protocol assessed the proliferation at day 56 and survival at day 77, whereas the number of POMC-EGFP cells, counted at day 56, reflects the integral of proliferation and/or survival from day 42 to 56. Because voluntary wheel running increases cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus (van Praag et al., 1999), we tested whether 2 weeks of running would affect neurogenesis in a A1254-exposed animals. In fact, running increased the number of newborn neurons in control and A1254-exposed animals to comparable levels, thus effectively rescuing the A1254-induced reduction (T = −0.18, P = 0.9; Fig. 2D and E).

Fig. 2.

Perinatal exposure to A1254 decreased the number of POMC-EGFP+ newborn granule cells in young adults. (A) Experimental timeline. The number of POMC-EGFP-positive cells was counted at P56 and after 2 weeks of voluntary running at P70. Proliferation was assessed using three BrdU injections at P56. Survival and differentiation were assessed 3 weeks after the last BrdU injection in wild-type mice. (B and C) Number of POMC-EGFP-positive cells (in green) at P56. (D and E), Number of newborn neurons after 2 weeks of running (POMC-EGFP-positive cells, in green). (F–J) Proliferation, survival, and differentiation between P56 and P77 as measured by BrdU. (I) Cells in S-phase (red: BrdU) in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (blue: nuclear staining using Hoescht). (J) Differentiation of newborn neurons 3 weeks after BrdU injections was measured as a ratio of BrdU+NeuN+/BrdU+ (Green: neuronal marker NeuN, blue: Hoescht). Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

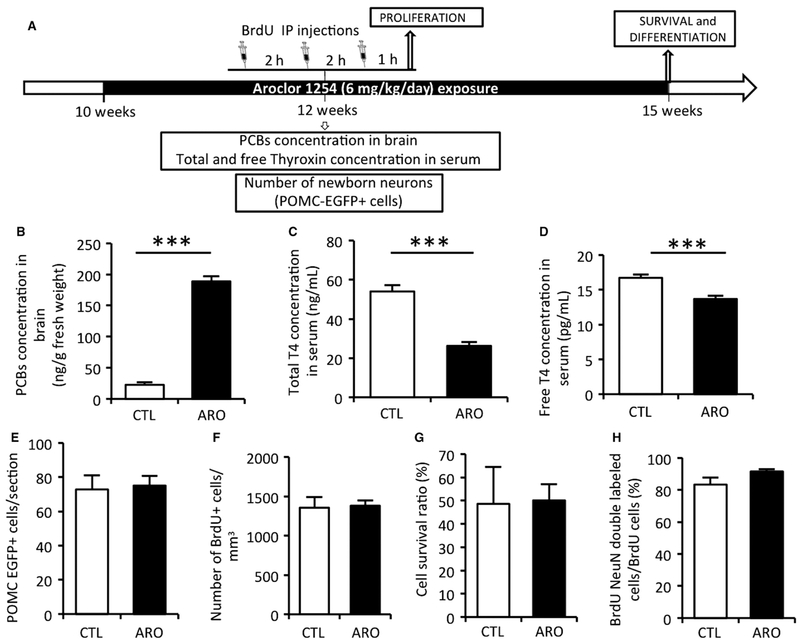

Adult exposure to A1254 reduced thyroid hormone levels, but did not alter hippocampal neurogenesis

In adults, exposed from 10 to 12 weeks of age, brain PCB levels were eight times higher than control (T = −18.69, P < 0.000001; Fig. 3B), yet threefold less than P56-exposed perinatally. Adult exposure did lead to hypothyroidism (Total T4: T = 7.43, P = 0.00002; Free T4: T = 4.76, P = 0.0007; Fig. 3C and D), but did not modify the number of POMC-EGFP+ cells (P = 0.8; Fig. 3E). Likewise, adult A1254 exposure did not affect proliferation (T = −0.18, P = 0.9), cell survival (T = −0.09, P = 0.9), or differentiation (T = 2.13, P = 0.08; Fig. 3F, G, and H). Thus, adult exposure was sufficient to reduce thyroid hormone levels but not sufficient to alter proliferation or survival of newborn neurons. Our experiments suggest that the lingering effect of perinatal exposure may be more important than acute exposure in the adult.

Fig. 3.

Adult exposure to A1254. (A) Experimental timeline. After 2 weeks of PCB exposure (from 10 to 12 weeks of age), PCB concentrations were measured in brains and total and free thyroxin levels were measured in serum. Proliferation was assessed after adult exposure to A1254 using three BrdU injections at 12 weeks of age in wild-type mice. Survival and differentiation were assessed 3 weeks after BrdU injections. The number of POMC-EGFP-positive cells was counted at 12 weeks after 2 weeks of PCBs exposure. (B) PCB concentrations in the brain of control and exposed mice. (C,D) Total and free thyroxin serum levels at 12 weeks in control or exposed animals. (E) The number of newborn neurons (POMC-EGFP-positive cells) after adult exposure. (F,G,H) Number of Brdu+ proliferating cells per mm3, percentage of surviving cells, and proportion of differentiated neurons in control and exposed mice. Data are mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

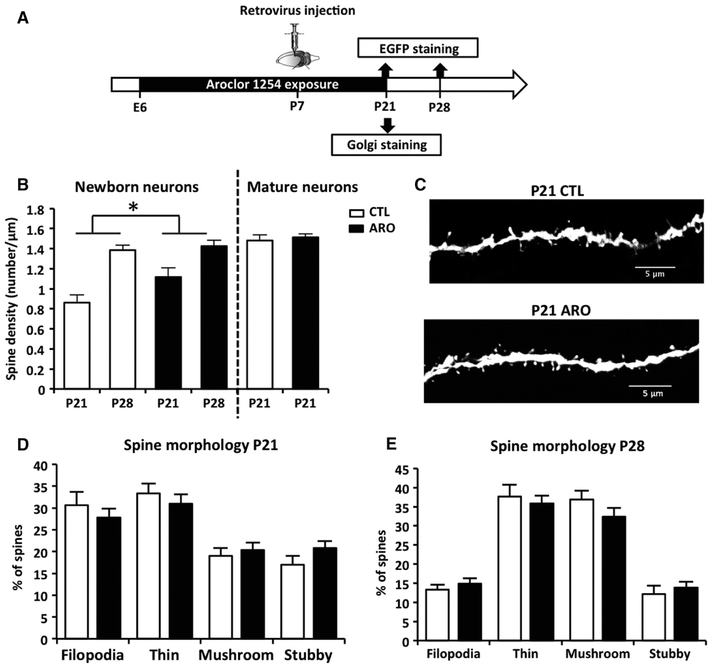

Neuronal morphology was unaffected by perinatal exposure to PCBs

Newborn granule cells were identified using stereotaxic injections of a retrovirus-expressing EGFP at P7 or P56 (Fig. 4A). As expected during this period of rapid synapse formation, spine density was higher in neurons at 21 days post-mitosis (‘P28’ mice injected at P7) compared to immature neurons at 14 days post-mitosis (‘P21’ mice injected at P7) in both control and A1254-exposed animals (two-way anova; main effect of age; F = 27 167, P = 0.000013). The treatment moderately but significantly increased spine density independently of age (two-way anova; main effect exposure to A1254; F = 5.52, P = 0.025; Fig. 4B and C). A1254 did not increase spine density in mature neurons labeled with the Golgi method (T = 0.50, P = 0.6; Fig. 4B). Similarly, A1254 perinatal exposure to A1254 did not affect spine density in adults (P77 injected at P56; CTL: 1.6 ± 0.1 spines/μm, n = 4; ARO: 1.6 ± 0.1 spines/μm, n = 4; T = 0.0000001, P = 1). There were also no effects of A1254 exposure on spine morphology (Fig. 4D and E) at P21 and P28. Total dendritic length (CTL: 728.1 ± 19.7 μm; ARO: 734.8 ± 35.3 μm, T = −0.12, P = 0.9), the number of segments (CTL: 7.8 ± 0.4 segments/neuron; ARO: 8.2 ± 0.3%, T = −0.91, P = 0.4), or dendritic complexity (Sholl analysis: CTL: 65.9 ± 1.2 branch crossings/neuron; ARO: 67.7 ± 3.4 branch crossings/neuron, T = −0.33, P = 0.7) was unchanged at P21.

Fig. 4.

Spine density of newborn granule cells following perinatal exposure to A1254. (A) Experimental timeline. A retrovirus-expressing EGFP was injected in the dentate gyrus at P7 to label newborn granule cells. Spine density and morphology were measured at P21, P28 (after injection of the retrovirus at P7). Spine density was also measured in mature granule cells using Golgi staining. (B) Spine density in newborn neurons labeled with a retrovirus in control (CTL) or exposed mice (ARO) and in mature neurons labeled with Golgi staining at P21. (C) Representative image of spine density at P21 in newborn neurons of exposed mice (ARO) compared to controls. (D and E) Proportion of immature (filopodia/thin) and mature (stubby and mushroom) spines at P21 and P28. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

A1254 disrupts functional development of excitatory synapses

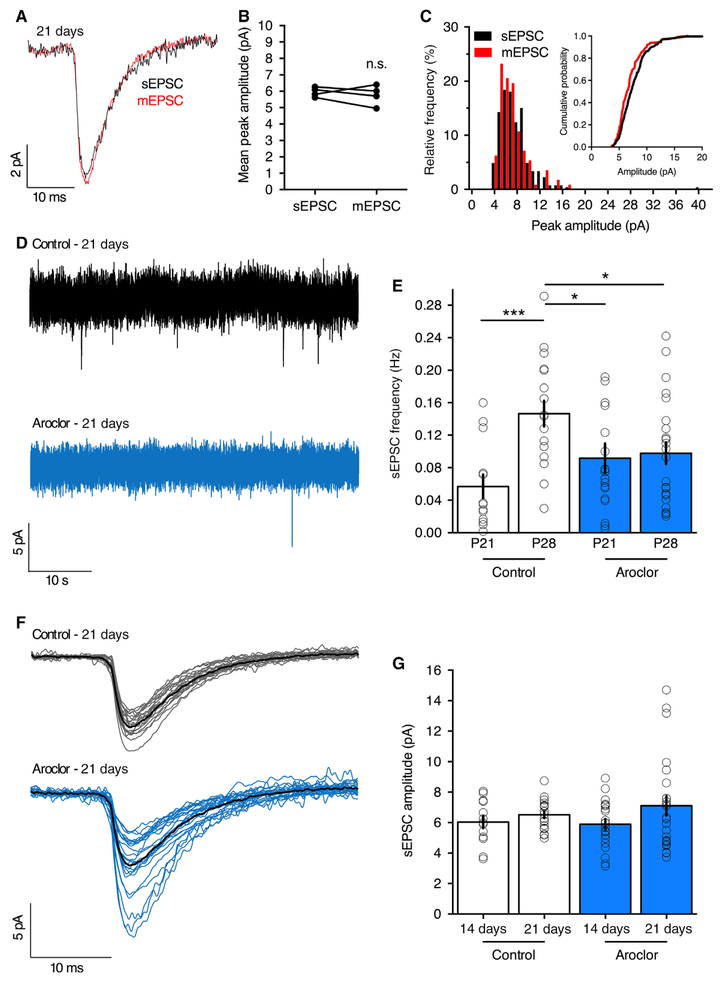

Critical changes in synaptic function can occur without changes in neuronal morphology. Newborn neurons undergo stereotyped development of synaptic innervation, first receiving GABAergic input during the first 2 weeks post-mitosis, followed by rapid development of excitatory inputs during the third and fourth week postmitosis (Overstreet-Wadiche & Westbrook, 2006). To examine if A1254 alters synaptic function, we used whole-cell recording in brain slices prepared from the dentate gyrus of control or A1254-treated animals. The amplitude of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs), i.e., in the absence of action potential blockade with tetrodotoxin, was the same as unitary release events (miniature EPSCs), indicating that most, if not all, sEPSCs resulted from single release events (Fig. 5A and C). We then compared sEPSCs in animals injected with retrovirus at P7 and recorded at P21 or P28. In control animals there was the expected developmental increase in sEPSCs frequency (Fig. 5E) comparable to the increase in dendritic spines (see Fig. 4B and C). However, A1254 exposure abolished the developmental increase in sEPSCs (Fig. 5D and E) despite the lack of any apparent changes in spine density at P28 between control and A1254 exposure (see Fig. 4B). Given that sEPSCs in our experiments reflect unitary events, the sEPSC amplitude should reflect the transmitter content of a vesicle or the number and/or synaptic clustering of post-synaptic receptors. Although A1254 did not alter the average sEPSC amplitude (Fig. 5F and G), there was an increase in the variability of sEPSC amplitudes in A1254-exposed mice (F-test, P < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

A1254 exposure and functional maturation of excitatory synapses. (A) Representative whole-cell recording from a labeled granule cell 21 days postinjection (P28 animals) reveals similar waveforms for spontaneous (sEPSC), or miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSC in the presence of 1 μM TTX). (B) Average peak amplitudes of EPSCs was not affected by TTX (paired t-test, T = 0.66, df = 3, P = 0.55, N = 4 cells). (C) Peak amplitude histograms for individual sEPSC and mEPSC events and cumulative probability plots (inset) display overlapping distributions, indicating sEPSCs represent single quantal release. (D) Sample traces of granule cells 21 days post-injection (P28 animals) showed less frequent spontaneous excitatory events in A1254-treated mice. (E) Between 14 and 21 days post-injection, the control sEPSC frequency increased, as expected (unpaired t-test, T = 3.91, df = 30, ***P = 0.0005; CTL: P21, N = 13 cells, four mice; 21 days, N = 19 cells, four mice) but not in A1254-treated mice (ARO; unpaired t-test, T = 0.27, df = 43; P = 0.78; ARO: 14 days, N = 21 cells, four mice; 21 days, N = 24 cells, five mice). Accordingly, P28 control cells show a higher sEPSC frequency than P28 ARO cells (unpaired t-test, T = 2.35, df = 41, *P = 0.02, control: N = 19 cells, aroclor: N = 24 cells). (F) The averaged sEPSC from each recorded cell 21 days post-injection is shown (gray: CTL, N = 19 cells, four mice; blue: ARO, N = 24 cells, five mice), with combined group averages in black. (G) The mean amplitudes were unaffected by A1254 at P21 and P28 (P21: unpaired t-test, T = 0.27, df = 32, P = 0.79, cell number as in E; P28: unpaired t-test, T = 0.8029, df = 41, P = 0.42). (E and G) display mean ± SEM, with individual cell averages shown as circles. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

In a separate cohort of A1254-exposed animals, we examined functional synaptic activity at P42, 21 days after the end of the exposure period, to determine if the developmental maturational defect persisted as A1254 levels decreased as the offspring reached adulthood. In control animals, the sEPSC frequency was 0.08 ± 0.01 Hz (n = 9 cells in three animals) compared to 0.10 ± 0.02 Hz (n = 10 cells from three animals, T = 0.83, P = 0.42) following A1254 exposure. The average sEPSC amplitude was 10.9 ± 0.7 pA in control and 9.5 ± 0.4 pA (n = 9 and 10 cells, T = 1.75, P = 0.1) following A1254 exposure. The block of the normal developmental increase in sEPSC frequency indicates that exposed animals were most vulnerable to A1254 during maturation of excitatory synapses on newborn granule cells. However, functional synaptic activity has normalized by the time granule cells reached full maturity in the adult (P42).

Discussion

Assessing the effects of PCBs in vivo

In our experiments, gestational and lactational exposure to A1254 led to PCB accumulation in the brain. Following a commonly used protocol of exposure (Lein et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2009), PCB concentrations were consistent with, or up to fivefold above, the high range of exposure for humans consuming high quantities of fatty fish (Dewailly et al., 1999). Specifically the range reported for each congener in human brain tissue was 1.8–200 ng/g lipid (Dewailly et al., 1999), and for our experiments the range was 209–1000 ng/g lipid. Although PCB production is now forbidden, these toxicants persist in the environment (Eubig et al., 2010), and negative effects on cognitive function that correlate with serum PCB levels are still being identified (Vreugdenhil et al., 2002; Stewart et al., 2008). Cognitive effects of PCB exposure in children generally manifest as effects on measures of attention and intelligence (Jacobson & Jacobson, 1996; Stewart et al., 2008; Sagiv et al., 2010; Ethier et al., 2015). In animal models, effect on measures of executive function and memory have been reported in several species [for review, see (Sable & Schantz, 2006)]. For example, in rodents perinatal exposure to the dose used in our experiments causes deficits in spatial memory (Roegge et al., 2000; Widholm et al., 2001) as well as long-term potentiation (Gilbert & Crofton, 1999), the later a widely accepted neural substrate of memory (Martinez & Derrick, 1996).

Because the dentate gyrus and, in particular, newborn granule cells (Aimone et al., 2014) are critical in spatial memory and synaptic plasticity, the disruption of excitatory synapses in our experiments could contribute to these observed cognitive deficits. Gilbert et al. (2000) noted an increase in the stimulus intensity to evoke LTP in adult rats from field potential recording following the same Aroclor exposure (E6-P21) as used here, but no effect on the EPSP slope amplitude. No changes were observed in a hippocampal-dependent task (Morris water maze). The synaptic phenotype we observed was in newly generated neurons, which would constitute only a small fraction of the LTP experiments in adult animals. Thus, it will be interesting to examine the effects of Aroclor more fully using a range of plasticity and behavioral approaches. Although we directed our experiments at newborn neurons because of their sensitivity to a variety of stressors, we cannot exclude that mature neurons or glial cells could also contribute to the effects of Aroclor we observed.

The prevalence of neurobehavioural disorders has been increasing worldwide (Landrigan et al., 2012) and subclinical impairment of brain functions is even more frequent. The causes of these increases are only partially understood, but environmental toxicants appear to be important contributors to this phenomenon (Grandjean & Landrigan, 2014; Bellanger et al., 2015). The magnitude of intellectual quotient loss due to environmental neurotoxicants is considered to be similar or even greater than the loss caused by medical events such as preterm birth, brain tumor or trauma, and congenital heart disease (Bellinger, 2012). In 2006, a systematic review of the clinical and epidemiological studies on neurotoxicity identified the PCBs among the five industrial chemicals that could reliably be classified as developmental neurotoxicants (Grandjean & Landrigan, 2006). Such developmental toxicity was consolidated by recent findings (Engel & Wolff, 2013). The cognitive changes in children exposed to PCBs suggest that early exposure could be critical (Jacobson & Jacobson, 1996; Stewart et al., 2008). However, in our experiments A1254 did not affect early proliferation and/or survival of newborn neurons despite the decrease in thyroid hormone levels during exposure. It is interesting and significant that the effects we observed are not on the initial stages of neurogenesis and survival, but rather during the stage of synaptic development. Given the lack of gross macroscopic changes with PCB exposure, the functional alterations we observed may be indicative of the underlying pathophysiology. Sensitive periods for developmental toxicity, as has been observed in children exposed to PCBs (Verner et al., 2010), could reflect differences in neuronal sensitivity to PCBs or to developmental differences in brain accumulation of PCBs. Our experiments provide some insights in that regard in that adult animals after 2 weeks of exposure to A1254 had threefold lower brain PCB levels compared to adult animals that were exposed from E6 to P21 and then assayed at P56. Thus, exposure during early brain development could lead to long-lasting effects on the brain, either from residual PCBs in brain tissue or maladaptive changes in neuronal networks that outlast the presence of PCBs, and could be consistent with the cognitive effects in children years after exposure during perinatal period. One example of such a delayed effect is the consequences of a neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion in rats on abnormal behaviors during or after adolescence, and which depend on prefrontal cortex (Tseng et al., 2008). More experiments will be required to resolve such issues.

A1254 and endocrine disruption

Several receptors systems have been proposed as targets for the action of PCBs. As described in Data S1, newborn and mature granule cells do express several of these targets including thyroid hormone receptors, the arylhydrocarbon receptor, and G protein-coupled receptor 30 and might be sensitive to PCB exposure through such mechanisms. However, our results cannot be easily explained by an effect on a single hormonal system. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the effects of PCB congeners in the developing brain including thyroid hormone-like actions (Zoeller, 2010) and activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, AhR, or estrogen receptors (Giera et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014). Although A1254 is an environmentally relevant mixture, it does include both dioxin-like and non-dioxin congeners, which can act on different combinations of targets (Parent et al., 2011). Both dioxin and non-dioxin-like PCBs are now known to affect behavior and cognitive functions (Fischer et al., 1998). A1254 can decrease circulating levels of thyroid hormones as we also observed at P7 and P21 (Crofton et al., 2000). However, total thyroxin was normal by P56 following perinatal exposure to A1254. Neurogenesis is sensitive to hypothyroidism (Zhang et al., 2009), thus it is likely that the reduced thyroid levels in our experiments did not result in the same degree of hypothyroidism as in prior studies (Desouza et al., 2005). We also cannot exclude compensatory effects of some A1254 congeners on estrogen signaling or on thyroid signaling downstream of thyroid receptors (DeCastro et al., 2006; Zoeller, 2010). However, it is clear that not all outcomes of PCB exposure such as changes in central neurotransmitter levels (Zahalka et al., 2001), alteration of cortex development (Naveau et al., 2014), eye opening, or tooth eruption (Goldey et al., 1995) correlate with reduced serum thyroid hormone levels.

A1254 exposure alters the functional maturation of excitatory synapses

The most striking result from our experiments was the dissociation between synaptic morphology and synaptic function. Previous studies of in vivo A1254 exposure have revealed variable effects on synaptic transmission in mature neurons in dentate gyrus or CA1 as assessed by extracellular recording (Gilbert & Crofton, 1999). In our whole-cell experiments, A1254 exposure occluded the normal developmental increase in the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs. Given the lack of functional maturation of synapses on newborn neurons without overt change in spine density, it seems likely that A1254 decreased the number of shaft synapses or silent synapses, neither of which would be represented in counts of dendritic spines. Unfortunately, detecting synapses on dendritic spines or shafts by using subcellular localization of AMPA receptors or PSD95 is nearly impossible in vivo because newborn neurons represent only 3% of the total granule cell population. Interestingly, shaft and silent synapses are more prominent during early synapse development, perhaps explaining why adult granule cells did not show a change in sEPSC frequency or amplitude. However, this may suggest that neurons are most vulnerable to the effects of A1254 during early synapse development as measured here in newborn hippocampal neurons. We speculate that the functional changes in excitatory synapses onto newborn neurons in the absence of overt changes in synaptic morphology may be characteristic of a wider range of neurodevelopmental disorders involving neural circuits such as autism.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Supplemental results.

Data S2. Supplemental methods.

Fig. S1. Exposure to A1254 leads to PCB accumulation in the brain and transiently decreased total and free thyroxin serum concentrations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology (ASP), The Belgian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (ASP, AG, and AP), the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (ASP and AP); Ellison Medical Foundation and NS080979 (GLW), the AXA Foundation fellowship (CC), and P30 NS061800 (OHSU confocal imaging core). We thank Stefanie Kaech Petrie for help with imaging.

Abbreviations

- A1254

Aroclor 1254

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- DG

dentate gyrus

- E6

embryonic day 6

- P21

postnatal day 21

- PCB

polychlorinated biphenyls

- POMC-EGFP

proopiomelanocortin – enhanced green fluorescent protein

- sEPSC

spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aimone JB, Li Y, Lee SW, Clemenson GD, Deng W & Gage FH (2014) Regulation and function of adult neurogenesis: from genes to cognition. Physiol. Rev, 94, 991–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger M, Demeneix B, Grandjean P, Zoeller RT & Trasande L (2015) Neurobehavioral deficits, diseases, and associated costs of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the European Union. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab, 100, 1256–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DC (2012) A strategy for comparing the contributions of environmental chemicals and other risk factors to neurodevelopment of children. Environ. Health Persp, 120, 501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal J (2007) Thyroid hormone receptors in brain development and function. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endoc, 3, 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, Covaci A & Schepens P (2003) Levels and chiral signatures of persistent organochlorine pollutants in human tissues from Belgium. Env. Res, 93, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofton KM, Kodavanti PR, Derr-Yellin EC, Casey AC & Kehn LS (2000) PCBs, thyroid hormones, and ototoxicity in rats: cross-fostering experiments demonstrate the impact of postnatal lactation exposure. Toxicol. Sci, 57, 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debier CPP, Dupont C, Joiris C & Comblin V (2003) Quantitative dynamics of PCB transfer from mother to pup during lactation in UK grey seals Halichoerus grypus. Mar. Ecol-Prog. Ser, 247, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- DeCastro BR, Korrick SA, Spengler JD & Soto AM (2006) Estrogenic activity of polychlorinated biphenyls present in human tissue and the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol, 40, 2819–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Aimone JB & Gage FH (2010) New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci., 11, 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desouza LA, Ladiwala U, Daniel SM, Agashe S, Vaidya RA & Vaidya VA (2005) Thyroid hormone regulates hippocampal neurogenesis in the adult rat brain. Mol. Cell Neurosci, 29, 414–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewailly E, Mulvad G, Pedersen HS, Ayotte P, Demers A, Weber JP & Hansen JC (1999) Concentration of organochlorines in human brain, liver, and adipose tissue autopsy samples from Greenland. Environ. HealthPersp., 107, 823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SM & Wolff MS (2013) Causal inference considerations for endocrine disruptor research in children’s health. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health, 34, 139–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier A-A, Muckle G, Jacobson SW, Ayotte P, Jacobson JL & Saint-Amour D (2015) Assessing new dimensions of attentional functions in children prenatally exposed to environmental contaminants using an adapted Posner paradigm. Neurotoxicol. Teratol, 51, 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubig PA, Aguiar A & Schantz SL (2010) Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environ. Health Persp, 118, 1654–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fång J, Nyberg E, Bignert A & Bergman Å (2013) Temporal trends of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans and dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls in mothers’ milk from Sweden, 1972–2011. Environ. Int, 60, 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer LJ, Seegal RF, Ganey PE, Pessah IN & Kodavanti PR (1998) Symposium overview: toxicity of non-coplanar PCBs. Toxicol. Sci, 41, 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea LAM (2008) Gonadal hormone modulation of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult male and female rodents. Brain Res. Rev, 57, 332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauger KJ, Kato Y, Haraguchi K, Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW, Bansal R & Zoeller RT (2004) Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) exert thyroid hormone-like effects in the fetal rat brain but do not bind to thyroid hormone receptors. Environ. Health Persp, 112, 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giera S, Bansal R, Ortiz-Toro TM, Taub DG & Zoeller RT (2011) Individual polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners produce tissue- and gene-specific effects on thyroid hormone signaling during development. Endocrinology, 152, 2909–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ME & Crofton KM (1999) Developmental exposure to a commercial PCB mixture (Aroclor 1254) produces a persistent impairment in long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus in vivo. Brain Res, 850, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ME, Mundy WR & Crofton KM (2000) Spatial learning and long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in animals developmentally exposed to Aroclor 1254. Toxicol. Sci, 57, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldey ES, Kehn LS, Lau C, Rehnberg GL & Crofton KM (1995) Developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (Aroclor 1254) reduces circulating thyroid hormone concentrations and causes hearing deficits in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm, 135, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, Toppari J & Zoeller RT (2015) EDC-2: the endocrine society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr. Rev, 36, E1–E150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P & Landrigan PJ (2006) Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet, 368, 2167–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P & Landrigan PJ (2014) Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol, 13, 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL & Jacobson SW (1996) Intellectual impairment in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. New Engl. J. Med, 335, 783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW & Humphrey HE (1990) Effects of in utero exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and related contaminants on cognitive functioning in young children. J. Pediatr, 116, 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan PJ, Lambertini L & Birnbaum LS (2012) A research strategy to discover the environmental causes of autism and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Environ. Health Persp, 120, a258–a260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein PJ, Yang D, Bachstetter AD, Tilson HA, Harry GJ, Mervis RF & Kodavanti PR (2007) Ontogenetic alterations in molecular and structural correlates of dendritic growth after developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls. Environ. Health Persp, 115, 556–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PF & Emerman M (1994) Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol, 68, 510–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luikart BW, Schnell E, Washburn EK, Bensen AL, Tovar KR & Westbrook GL (2011) Pten knockdown in vivo increases excitatory drive onto dentate granule cells. J. Neurosci, 31, 4345–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luikart BW, Perederiy JV & Westbrook GL (2012) Dentate gyrus neurogenesis, integration and microRNAs. Behav. Brain Res, 227, 348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JL & Derrick BE (1996) Long-term potentiation and learning. Annu. Rev. Psychol, 47, 173–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveau E, Pinson A, Gérard A, Nguyen L, Charlier C, Thomé J-P, Zoeller RT, Bourguignon J-P et al. (2014) Alteration of rat fetal cerebral cortex development after prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls. PLoS One, 9, e91903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet LS, Hentges ST, Bumaschny VF, de Souza FS, Smart JL, Santangelo AM, Low MJ, Westbrook GL et al. (2004) A transgenic marker for newly born granule cells in dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci, 24, 3251–3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet-Wadiche LS & Westbrook GL (2006) Functional maturation of adult-generated granule cells. Hippocampus, 16, 208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent AS, Naveau E, Gerard A, Bourguignon JP & Westbrook GL (2011) Early developmental actions of endocrine disruptors on the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex. J Toxicol Env Heal B, 14, 328–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patandin S, Lanting CI, Mulder PG, Boersma ER, Sauer PJ & Weisglas-Kuperus N (1999) Effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on cognitive abilities in Dutch children at 42 months of age. J. Pediatr, 134, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perederiy JV, Luikart BW, Washburn EK, Schnell E & Westbrook GL (2013) Neural injury alters proliferation and integration of adult-generated neurons in the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci, 33, 4754–4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G & Gage FH (1999) Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci, 2, 266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roegge CS, Seo BW, Crofton KM & Schantz SL (2000) Gestational-lactational exposure to Aroclor 1254 impairs radial-arm maze performance in male rats. Toxicol. Sci, 57, 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable HJK & Schantz SL (2006) Executive function following developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): what animal models have told us In Levin ED & Buccafusco JJ (Eds), Animal Models of Cognitive Impairment. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 147–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv SK, Thurston SW, Bellinger DC, Tolbert PE, Altshul LM & Korrick SA (2010) Prenatal organochlorine exposure and behaviors associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children. Am. J. Epidemiol, 171, 593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PW, Lonky E, Reihman J, Pagano J, Gump BB & Darvill T (2008) The relationship between prenatal PCB exposure and intelligence (IQ) in 9-year-old children. Environ. Health Persp, 116, 1416–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, Lewis BL, Hashimoto T, Sesack SR, Kloc M, Lewis DA & O’Donnell P (2008) A neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion causes functional deficits in adult prefrontal cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci, 28, 12691–12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verner M-A, Plusquellec P, Muckle G, Ayotte P, Dewailly E, Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL, Charbonneau M et al. (2010) Alteration of infant attention and activity by polychlorinated biphenyls: unravelling critical windows of susceptibility using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Neurotoxicology, 31, 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil HJI, Lanting CI, Mulder PGH, Boersma ER & Weisglas-Kuperus N (2002) Effects of prenatal PCB and dioxin background exposure on cognitive and motor abilities in Dutch children at school age. J. Pediatr, 140, 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widholm JJ, Clarkson GB, Strupp BJ, Crofton KM, Seegal RF & Schantz SL (2001) Spatial reversal learning in Aroclor 1254-exposed rats: sex-specific deficits in associative ability and inhibitory control. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm, 174, 188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Kim KH, Phimister A, Bachstetter AD, Ward TR, Stackman RW, Mervis RF, Wisniewski AB et al. (2009) Developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls interferes with experience-dependent dendritic plasticity and ryanodine receptor expression in weanling rats. Environ. Health Persp, 117, 426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahalka EA, Ellis DH, Goldey ES, Stanton ME & Lau C (2001) Perinatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls Aroclor 1016 or 1254 did not alter brain catecholamines nor delayed alternation performance in Long-Evans rats. Brain Res. Bull, 55, 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Blomgren K, Kuhn HG & Cooper-Kuhn CM (2009) Effects of postnatal thyroid hormone deficiency on neurogenesis in the juvenile and adult rat. Neurobiol. Dis, 34, 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Lu M, Wang C, Du J, Zhou P & Zhao M (2014) Characterization of estrogen receptor α activities in polychlorinated biphenyls by in vitro dual-luciferase reporter gene assay. Environ. Pollut, 189, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller TR (2010) Environmental chemicals targeting thyroid. Horm, 9, 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental results.

Data S2. Supplemental methods.

Fig. S1. Exposure to A1254 leads to PCB accumulation in the brain and transiently decreased total and free thyroxin serum concentrations.