Clinical case

A previously healthy 2-year and 9-month old boy was brought to the emergency department for a 6-day history of weakness in the legs and frequent falls, rendering him unable to walk 1 day before admission. He did not have pain, dysphagia, bladder dysfunction, or sensory symptoms. There was no history of trauma, but he developed diarrhea 3 days before symptom onset. Family history was negative for consanguinity or neurologic diseases. At examination, he had bilateral leg weakness requiring substantial aid to walk a few steps and was unable to stand up from the floor. He had absent tendon reflexes in the lower extremities and flexor plantar responses. Strength and reflexes in upper extremities and the rest of the examination were normal. CSF showed a protein concentration of 125 mg/dL (NR: 15–45), with normal white blood cell count and glucose concentration. Blood cell count and chemistry were normal, and stool culture was negative. Nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and EMG showed decreased amplitudes in both peroneal nerves (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A131). The patient was treated with IV immunoglobulins (IVIg) 2 g/kg administered in 3 days. During the next 2 weeks, there was mild improvement in motor strength as he was able to walk and stand up with support (the Guillain-Barré syndrome disability scale [GBSds]1 score remained 3), and he was discharged home. Two weeks later (4 weeks after symptom onset), he was brought back for worsening weakness in the legs and new onset weakness in the arms. This time, the examination revealed weakness in legs and arms, generalized areflexia, and impossibility to stand up from the floor (GBSds 4). Repeat CSF studies showed a protein concentration of 148 mg/dL and normal white blood cell count and glucose level. No toxic or infectious etiologies were identified, and serum was negative for ganglioside antibodies. NCSs showed prolonged distal motor latencies, conduction slowing, and decreased amplitude of compound muscle action potentials, along with EMG features of chronic denervation, fibrillation, and positive sharp waves (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A131). Treatment with IVIg was ineffective, but IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/d for 5 days) resulted in substantial improvement, leaving the patient with normal strength except for mild distal lower extremity weakness (GBSds 1).

One year later, after an episode of diarrhea, the patient developed similar clinical and electrophysiologic abnormalities confined to the lower extremities (GBSds 3) fulfilling clinical and electrophysiologic criteria for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). This time, the symptom recrudescence improved with IVIg, and he returned to his baseline (GBSds 1).

A recent follow-up, 5 years after symptom onset, showed that the neurologic deficits were stable, and the patient had not had further relapses. Current serum studies for antibodies against components of the nodal and paranodal regions of peripheral nerves were negative, but analysis of archived serum and CSF samples obtained at disease onset (5 years earlier) showed intense reactivity with teased nerve fibers from pig and human embrionic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing contactin-1 demonstrating the presence of these antibodies in both assays (figure).

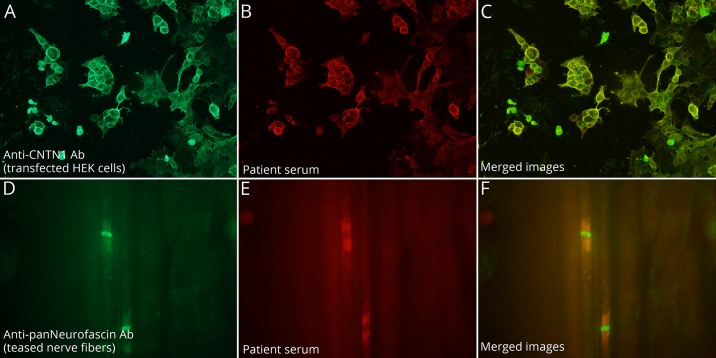

Figure. Demonstration of anti–contactin-1 antibodies in a serum of a child with CIDP.

The presence of anti–contactin-1 antibodies was confirmed with contactin-1–transfected human embrionic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. Patient serum (B) showed strong reactivity against contactin-1 and colocalized with the reactivity of a commercial antibody (A) in merged images (C). Patient serum showed strong reactivity against the paranode on pig teased nerve fibers (E) and colocalized with the reactivity of a commercial antibody (D) in merged images (F).

Discussion

CIDP is a rare, disabling and treatable disease in children. Antibodies against proteins of the paranode and node of Ranvier (contactin-1, contactin-associated protein 1, and neurofascin 155 and 186) have been recently described in several subsets of patients with CIDP.2 In particular, CIDP associated with antibodies against the 155 isoform of neurofascin develop at younger ages, including pediatric patients.2,3 However, antibodies against contactin-1 have never been reported in children. These antibodies are predominantly IgG4 subclass and associate with a form of CIDP that manifests with an aggressive symptom onset, resembling Guillain-Barré syndrome, with predominant motor weakness, ataxia, and absent or limited response to IVIg or steroids but an excellent response to rituximab.4,5 This disorder represents approximately 2%–4% of all patients with CIDP. Clinical improvement is usually accompanied by a decrease of contactin-1 antibody titers.6,7 Our patient had a similar presentation with predominant motor involvement and NCSs and EMG suggesting demyelinating features accompanied by early axonal damage. However, he had a less aggressive course compared with that described in adults. Because at the last follow-up, 5 years after disease onset, the patient's deficits had remained stable for 4 years, treatment with rituximab was not considered. It is likely that an earlier recognition of the disorder, by examining contactin-1 antibodies at disease onset, would have prompted treatment with rituximab and perhaps prevented some of his deficits.

Experience with this patient indicates that contactin-1 antibody-associated CIDP can occur in children. Testing for antibodies against nodo-paranodal proteins is important in pediatric patients with CIDP refractory to conventional therapies because antibody findings can help optimizing their care.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This study was supported in part by Instituto Carlos III/FEDER (FIS 17/00234 (J.D.), FIS16/00627 (L.Q.), CM17/00054 (D.N.)); CIBERER #CB15/00010 (T.A., J.D., L.Q.); AGAUR (Generalitat de Catalunya); Pla estratègic de recerca i innovació en salut (PERIS), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya (SLT006/17/00131, L.Q.); and Fundació CELLEX (J.D.).

Disclosure

J. Dalmau receives royalties from Athena Diagnostics for the use of Ma-2 as an autoantibody test and from Euroimmun AG for the use of NMDA, GABAB receptor, GABAA receptor, DPPX, and IgLON5 as autoantibody tests and is Editor of Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. The other authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Hughes RA, Newsom-Davis JM, Perkin GD, Pierce JM. Controlled trial prednisolone in acute polyneuropathy. Lancet 1978;2:750–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Querol L, Devaux J, Rojas-Garcia R, Illa I. Autoantibodies in chronic inflammatory neuropathies: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Neurol 2017;13:533–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vural A, Doppler K, Meinl E. Autoantibodies against the node of ranvier in seropositive chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: diagnostic, pathogenic, and therapeutic relevance. Front Immunol 2018;14:1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Querol L, Nogales-Gadea G, Rojas-Garcia R, et al. . Antibodies to contactin-1 in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol 2013;73:370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miura Y, Devaux JJ, Fukami Y, et al. . Contactin 1 IgG4 associates to chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy with sensory ataxia. Brain 2015;138:1484–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Querol L, Rojas-García R, Diaz-Manera J, et al. . Rituximab in treatment-resistant CIDP with antibodies against paranodal proteins. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2:e149 doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doppler K, Appeltshauser L, Wilhelmi K, et al. . Destruction of paranodal architecture in inflammatory neuropathy with anti-contactin-1 autoantibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]