Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness as assessed with optical coherence tomography differs between patients with progressive MS (P-MS) according to age and disease activity.

Methods

In this retrospective longitudinal analysis, differences in terms of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), ganglion cell layer + inner plexiform layer (GCIPL), INL and T1/T2 lesion volumes (T1LV/T2LV) were assessed between 84 patients with P-MS and 36 sex- and age-matched healthy controls (HCs) and between patients stratified according to age (cut-off: 51 years) and evidence of clinical/MRI activity in the previous 12 months

Results

pRNFL and GCIPL thickness were significantly lower in patients with P-MS than in HCs (p = 0.003 and p < 0.0001, respectively). INL was significantly thicker in patients aged < 51 years compared to the older ones and HCs (38.2 vs 36.5 and 36.7 μm; p = 0.038 and p = 0.04, respectively) and in those who presented MRI activity (new T2/gadolinium-enhancing lesions) in the previous 12 months compared to the ones who did not and HCs (39.5 vs 36.4 and 36.7 μm; p = 0.003 and p = 0.008, respectively). Recent MRI activity was significantly predicted by greater INL thickness (Nagelkerke R2 0.36, p = 0.001).

Conclusions

INL thickness was higher in younger patients with P-MS with recent MRI activity, a criterion used in previous studies to identify a specific subset of patients with P-MS who best responded to disease-modifying treatment. If this finding is confirmed, we suggest that INL thickness might be a useful tool in stratification of patients with P-MS for current and experimental treatment choice.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides measures of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) and retinal layer volumes. The progressive thinning of pRNFL and ganglion cell layer + inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) is considered biomarkers of neurodegeneration in MS.1 Conversely, the thickness of inner nuclear layer (INL) has been recently proposed as a measure of inflammatory activity in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RR-MS).2,3 However, INL has not been extensively studied in patients with progressive MS (P-MS).

Phase III trials have shown that disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) are more efficacious in subgroups of progressive patients aged <51 years and with presence of gadolinium-enhancing lesions on MRI.4 Therefore, we sought to investigate whether INL thickness can reflect inflammation-related differences in patients with P-MS with different range of age and disease activity. A simple and cost-efficient retinal measure could help in identifying patients with P-MS who may benefit from DMTs.

The aims of our study were to (1) characterize INL in patients with P-MS and (2) investigate whether INL thickness differs between patients with P-MS stratified according to age and evidence of disease activity.

Methods

Study design

In this retrospective longitudinal cohort study, 90 patients suffering from P-MS and 36 sex- and age-matched healthy controls (HCs) were recruited from 2 MS centers between 2014 and 2018 (64 patients and 16 HCs from San Martino-IST Hospital, Genova, Italy; 26 patients and 20 HCs from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY). Inclusion criteria were (1) age 18–80 years, (2) MS diagnosis according to the 2010 McDonald's criteria,5 and (3) progressive course according to Lublin's criteria.6 If treated, patients needed to be stable on their DMT for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria were (1) substantial ophthalmologic pathologies (including iatrogenic optic neuropathy/diabetes/uncontrolled hypertension), (2) refractive errors ± 6 D, and (3) previous (any time during disease course) bilateral optic neuritis (ON). In patients with previous unilateral ON, only the nonaffected eye was analyzed (n = 6, none occurring during the previous 12 months). In patients without history of ON and HC, OCT metrics were averaged over the 2 eyes.

All subjects underwent (1) assessment of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score and (2) standardized spectral domain-OCT protocols (Spectralis, Heidelberg-Engineering), performed and processed by a single certified neurologist as previously described,7 in accordance with the APOSTEL recommendations8 (details available on request). Global-pRNFL, GCIPL, and INL thickness were measured (Heidelberg Eye Explorer mapping software version 6.0.9.0.). Scans violating international-consensus quality-control criteria (OSCAR-IB)9 were excluded (n = 6 patients excluded due to poor OCT quality; n = 84 patients entered the final analysis); (3) MRI using 1.5T (Avanto, Siemens Healthcare) (n = 27) or 3T (Philips Achieva) (n = 57) scanner. Axial spin-echo 2D T2-weighted (3-mm thick continuous slices covering the entire brain) and 3D T1-weighted (1 mm3 isotropic) sequences were standardized between centers. T2/T1 lesion volumes (T2LV/T1LV) were measured (Jim version 7.0; XInapse Systems Ltd, United Kingdom) by an experienced operator blinded to subjects' identities.

To assess clinical/MRI activity in the year prior to enrollment, we retrospectively revised patients' charts and collected the number of clinical relapses/EDSS score in the previous 12 months and of new T2/gadolinium-enhancing lesions with respect to a clinical MRI performed 12 months earlier (MRI data available for n = 77 patients).

Patients were stratified according to (1) age (> or < 51-years-old)4; (2) evidence of disease activity (presence of at least one of (a) clinical activity: occurrence of ≥1 relapses and/or 1 EDSS point increase or 0.5 if baseline EDSS ≥ 5.5; or (b) MRI activity: new T2-and/or gadolinium-enhancing lesions) in the previous 12 months.

Statistics

Analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM; X). Demographic and T1LV/T2LV differences between groups were analyzed using χ2, Mann-Whitney/Kruskal-Wallis, and independent-samples t tests where appropriate. For OCT-derived measures, we used analysis of covariance. Patients vs controls analyses were adjusted for age and gender; age-related subgroup analyses (n = 84) were adjusted for gender, disease duration, treatment, and MRI scanner; for clinical/MRI activity-related subgroup analyses, we added age to the covariates listed above. The relationships of OCT metrics with T1LV/T2LV and MRI activity in the previous 12 months were assessed with Spearman correlation and logistic regression analysis (adjusted for gender, age, disease duration, treatment, and MRI scanner), respectively. All p values were 2-sided and considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05. Since our study is exploratory, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the local ethical committees and written informed consent was obtained from all participants according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

Raw data are available upon appropriate request.

Results

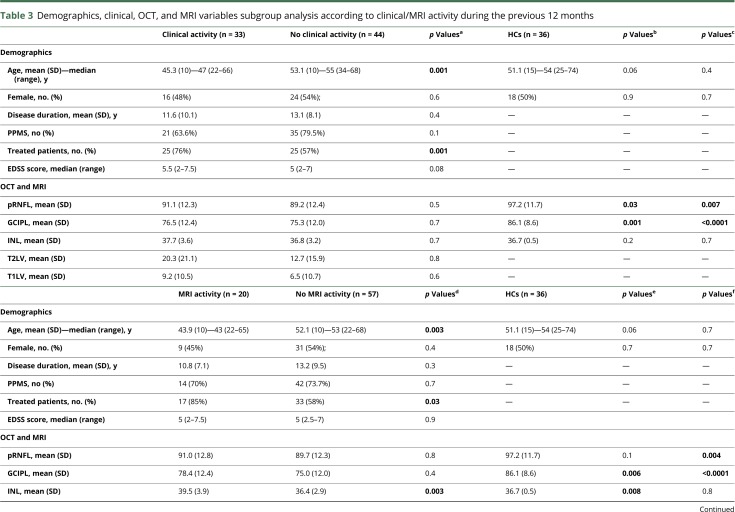

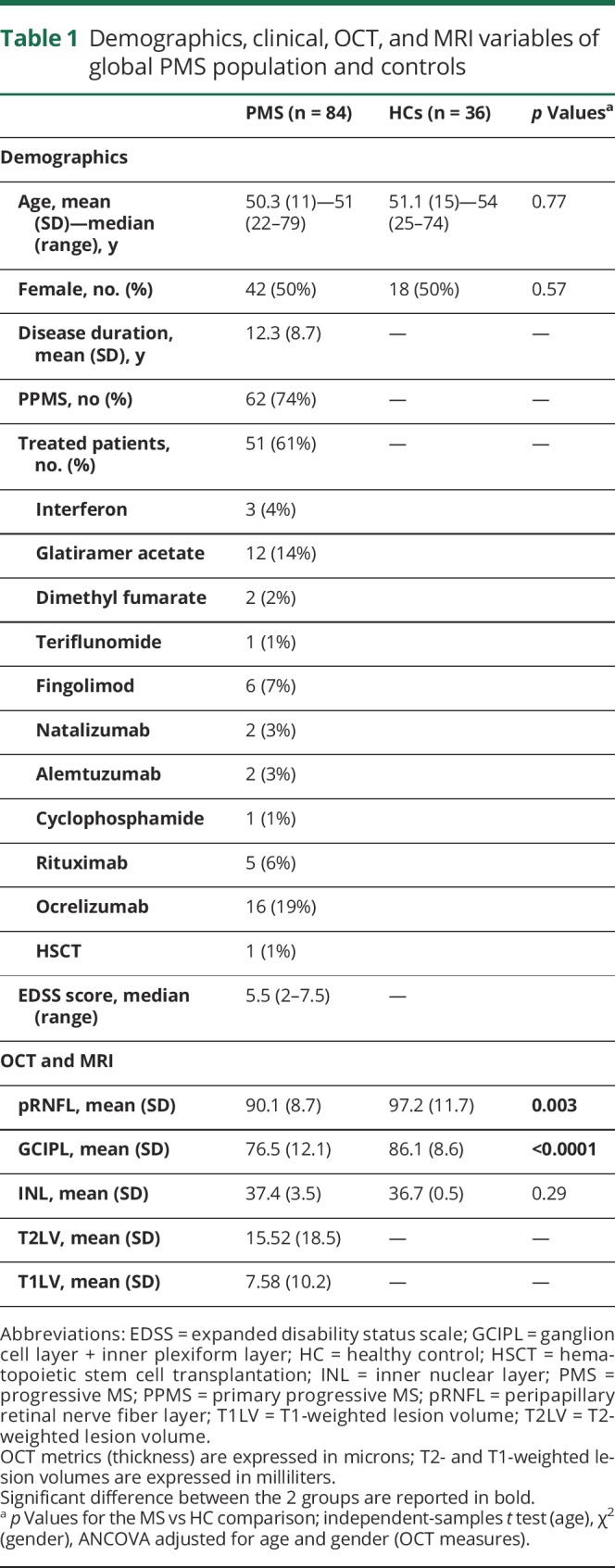

Demographic, clinical, OCT, and MRI data regarding 84 patients with P-MS (62 primary P-MS, 22 secondary P-MS) and 36 HCs are reported in table 1. No one presented microcystic macular edema (MME). Patients showed a significantly reduced pRNFL (−7.1 ± 2.3 μm, p = 0.003) and GCIPL (−9.6 ± 2.2 μm, p < 0.0001) thickness compared to HCs; no significant differences emerged in terms of INL. No significant correlations were found between T1LV/T2LV and pRNFL (p = 0.8/p = 0.9, respectively), GCIPL (p = 0.1/p = 0.3, respectively), and INL (p = 0.3/p = 0.06, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical, OCT, and MRI variables of global PMS population and controls

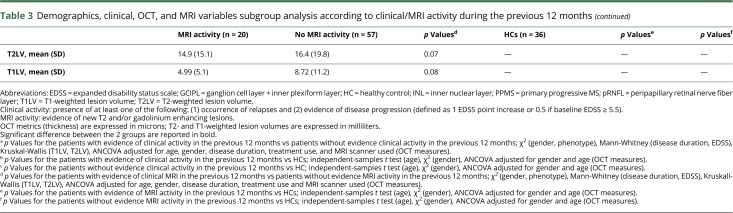

Subgroup analysis are reported in table 2 (age-related stratification) and table 3 (clinical/MRI activity-related stratification) and shown in figure e-1 (links.lww.com/NXI/A138). Patients aged <51 years had significantly thicker INL than the older ones and HCs (38.2 vs 36.5 and 36.7 μm; p = 0.038 and p = 0.04, respectively). As expected,10 no age-related INL differences emerged in HC. INL was thicker in patients who showed disease activity in the previous 12 months (38.05 μm) compared to the ones who did not (36.2 μm), but such difference did not reach significance (p = 0.1). Accordingly, we stratified patients separately considering clinical (relapses/progression) or MRI activity. A thicker INL was observed in patients who showed MRI activity in the previous 12 months compared to those who did not and controls (39.5 vs 36.4 and 36.7 μm; p = 0.003 and p = 0.008, respectively). The mean differences in OCT-derived metrics and 95% CI for all comparisons are reported in table e-1 (links.lww.com/NXI/A139).

Table 2.

Demographics, clinical, OCT, and MRI variables of age-related subgroup analysis

Table 3.

Demographics, clinical, OCT, and MRI variables subgroup analysis according to clinical/MRI activity during the previous 12 months

Logistic regression models testing INL as a predictor of MRI activity in the previous 12 months explained 35% of variance in the outcome (Nagelkerke R2 0.36, p = 0.001); the inclusion of pRNFL and GCIPL did not improve prediction of the model (Nagelkerke R2 0.37, p = 0.004), as INL remained the only significant contributor to the equation (pRNFL p = 0.47; GCIPL p = 0.49; INL p = 0.009).

Discussion

Our results confirm that despite reduced pRNFL and GCIPL thickness,1,7 no significant differences emerged in terms of INL in P-MS compared to controls.2 However, when we stratified patients according to age and MRI activity, INL was significantly thicker in patients with P-MS aged <51 years and those with recent T2-/gadolinium-enhancing lesions. Furthermore, even accounting for age, INL was able to significantly classify patients with P-MS according to recent MRI activity. Different possible mechanisms involved in INL thickening in MS have been proposed, including the presence of MME, inflammation-related dynamic fluid shifts, noninflammation-related traction following RNFL/GCIPL atrophy.2,3 We did not observe MME or statistically significantly lower GCIPL/pRNFL thickness in those subgroups of patients with thicker INL (aged <51 years and with recent MRI activity). Taken together, our results provide preliminary evidence supporting the role of INL as a marker of ongoing inflammatory processes, not only in RR-MS3 but also in patients with P-MS. This is particularly promising given the paucity of validated outcome measures measuring disease activity in P-MS. The retrospective design, limited and unequal sample size of HCs and patients, inclusion of both primary- and secondary-P-MS subjects, and the absence of spinal cord activity data should be considered limitations of our study. Prospective and multicentric studies confirming our results are needed. This may lead to the identification of a cutoff to use in clinical practice and clinical trials to select patients with P-MS more likely to respond to therapy.

Conclusions

INL thickness was higher in younger patients with P-MS with higher/recent MRI activity, supposed to best benefit from treatment. If our finding is confirmed, INL might be considered a useful tool for the stratification of patients with P-MS for current and experimental treatment choice.

Glossary

- DMT

disease-modifying treatment

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- GCIPL

ganglion cell layer + inner plexiform layer

- HC

healthy control

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- LV

lesion volume

- MME

microcystic macular edema

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- ON

optic neuritis

- P-MS

progressive MS

- pRNFL

peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer

- RR

relapsing-remitting

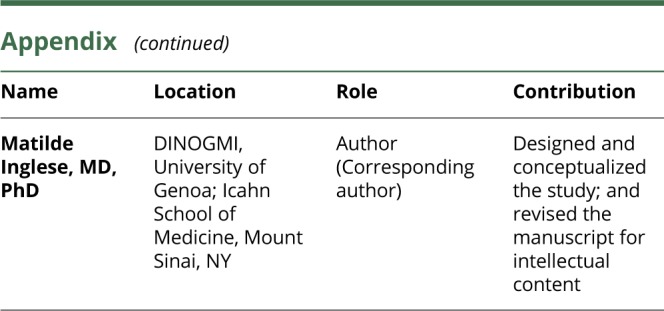

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

The study was in part supported by the NMSS RG 5120-A-3 to MI.

Disclosure

M. Cellerino, C. Cordano, G. Boffa, G. Bommarito, M. Petracca, E. Sbragia, G. Novi, C. Lapucci, E. Capello report no disclosures. A. Uccelli received grants and contracts from FISM, Novartis, Fondazione Cariplo, Italian Ministry of Health; received honoraria or consultation fees from Biogen, Roche, Teva, Merck, Genzyme, Novartis. M. Inglese: received research grants from NIH, DOD, NMSS, FISM, and Teva Neuroscience. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Petzold A, Balcer LJ, Calabresi PA, et al. Retinal layer segmentation in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Ibrahim MA, et al. Microcystic macular oedema, thickness of the inner nuclear layer of the retina, and disease characteristics in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knier B, Schmidt P, Aly L, et al. Retinal inner nuclear layer volume reflects response to immunotherapy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2016;139:2855–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawker K, O'Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol 2009;66:460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 Revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen J et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology 2014;83:278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petracca M, Cordano C, Cellerino M, et al. Retinal degeneration in primary-progressive multiple sclerosis: a role for cortical lesions? Mult Scler J 2017;23:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz-Herranz A, Balk LJ, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. IMSVISUAL consortium. The APOSTEL recommendations for reporting quantitative optical coherence tomography studies. Neurology 2016;86:2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schippling S, Balk LJ, Costello F, et al. Quality control for retinal OCT in multiple sclerosis: validation of the OSCAR-IB criteria. Mult Scler J 2015;21:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demirkaya N, van Dijk HW, van Shuppen SM, et al. Effect of age on individual retinal layer thickness in normal eyes as measured with spectral-domain ocptical coherence tomography. Invest Ophtalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:4934–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data are available upon appropriate request.