Abstract

Reelin controls neuronal migration and layer formation. Previous studies in reeler mice deficient in Reelin focused on the result of the developmental process in fixed tissue sections. It has remained unclear whether Reelin affects the migratory process, migration directionality, or migrating neurons guided by the radial glial scaffold. Moreover, Reelin has been regarded as an attractive signal because newly generated neurons migrate toward the Reelin-containing marginal zone. Conversely, Reelin might be a stop signal because migrating neurons in reeler, but not in wild-type mice, invade the marginal zone. Here, we monitored the migration of newly generated proopiomelanocortin-EGFP-expressing dentate granule cells in slice cultures from reeler, reeler-like mutants and wild-type mice of either sex using real-time microscopy. We discovered that not the actual migratory process and migratory speed, but migration directionality of the granule cells is controlled by Reelin. While wild-type granule cells migrated toward the marginal zone of the dentate gyrus, neurons in cultures from reeler and reeler-like mutants migrated randomly in all directions as revealed by vector analyses of migratory trajectories. Moreover, live imaging of granule cells in reeler slices cocultured to wild-type dentate gyrus showed that the reeler neurons changed their directions and migrated toward the Reelin-containing marginal zone of the wild-type culture, thus forming a compact granule cell layer. In contrast, directed migration was not observed when Reelin was ubiquitously present in the medium of reeler slices. These results indicate that topographically administered Reelin controls the formation of a granule cell layer.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Neuronal migration and the various factors controlling its onset, speed, directionality, and arrest are poorly understood. Slice cultures offer a unique model to study the migration of individual neurons in an almost natural environment. In the present study, we took advantage of the expression of proopiomelanocortin-EGFP by newly generated, migrating granule cells to analyze their migratory trajectories in hippocampal slice cultures from wild-type mice and mutants deficient in Reelin signaling. We show that the compartmentalized presence of Reelin is essential for the directionality, but not the actual migratory process or speed, of migrating granule cells leading to their characteristic lamination in the dentate gyrus.

Keywords: Dab1 phosphorylation, hippocampus, live imaging, neuronal migration, reeler-like, Reelin

Introduction

The extracellular matrix protein Reelin plays an important role in neuronal migration and the formation of laminated brain structures, such as the neocortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (D'Arcangelo et al., 1995; Rakic and Caviness, 1995; Curran and D'Arcangelo, 1998; Frotscher, 1998, 2010; Tissir and Goffinet, 2003; Förster et al., 2006; Zhao and Frotscher, 2010; O'Dell et al., 2015; Chai et al., 2016; Dillon et al., 2017). Reelin is the molecule deleted in the natural mouse mutant reeler (Falconer, 1951), and much has been learned in recent decades about the diverse functions of Reelin, its signaling cascade, and the migration defects in the reeler mouse and in mutants deficient in Reelin signaling molecules. Reelin signaling involves the lipoprotein receptors apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) (D'Arcangelo et al., 1999; Trommsdorff et al., 1999), and the adaptor protein Disabled 1 (Dab1), which is phosphorylated by src family kinases upon binding of Reelin to its receptors (Howell et al., 1997, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1997; Ware et al., 1997; Franco et al., 2011). Dab1-deficient mouse mutants and double knock-out mice deficient in ApoER2 and VLDLR show a reeler-like phenotype with severe migration defects in laminated brain areas (Howell et al., 1997; Trommsdorff et al., 1999). In addition to these lipoprotein receptors, α3β1 integrins were shown to bind Reelin and control neuronal migration (Dulabon et al., 2000). Reelin interacts with Notch signaling (Hashimoto-Torii et al., 2008; Sibbe et al., 2009) and was found to phosphorylate the actin-depolymerizing protein cofilin, resulting in stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton (Chai et al., 2009). Moreover, Reelin is important for the formation of defined projections (Del Rio et al., 1997) and for the determination of proximodistal dendritic segments of pyramidal neurons (Kupferman et al., 2014). In adult animals, Reelin signaling plays a role in learning and memory processes (Beffert et al., 2005).

Despite this wealth of data, it has remained unclear how Reelin affects the actual migratory process of newly generated neurons. This holds particularly true for the dentate gyrus, one of the few brain regions with persistent neurogenesis. Here, granule cells generated in the hilus migrate for only short distances and form a compact neuronal layer in wild-type animals. In contrast, in reeler and reeler-like mutants, granule cells are scattered all over the dentate area and often invade the inner molecular layer (Zhao et al., 2003). How does Reelin, synthesized by Cajal–Retzius (CR) cells (D'Arcangelo et al., 1995; Del Rio et al., 1997; Lambert de Rouvrouit and Goffinet, 1998; Meyer and Goffinet, 1998; Rice and Curran, 2001), control the strict lamination of the granule cells? In the dentate gyrus, CR cells in the outer molecular layer synthesize Reelin. Does Reelin prevent the granule cells from invading the molecular layer? Does Reelin act on granule cell motility and the actual migratory process, its speed, or directionality? By using hippocampal slice cultures and real-time microscopy, we provide a comprehensive analysis of the migratory trajectories of newly generated granule cells in the developing dentate gyrus of wild-type animals and various mutants deficient in molecules of the Reelin signaling cascade. Moreover, we were able to visualize the rescue of a laminated organization in a reeler dentate gyrus in a coculture to a wild-type hippocampus, which provided Reelin to the reeler dentate gyrus in a normotopic position. The results showed that Reelin from the molecular layer controls the directionality of granule cell migration, but it did not affect nuclear translocation or migratory speed.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-EGFP transgenic mice (Overstreet et al., 2004) were obtained from Dr. Gary L. Westbrook (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon). Wild-type (C57BL/6), reeler (B6C3Fe-a/a-Relnrl), ApoER2 knock-out (ApoER2−/−), VLDLR knock-out (VLDLR−/−), and Dab1 knock-out (scrambler) mice were obtained from Dr. Joachim Herz (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas). Reeler, ApoER2 knock-out, VLDLR knock-out, and Dab1 knock-out mice were each cross-bred with POMC-EGFP transgenic mice to generate reeler-POMC, ApoER2−/−-POMC, VLDLR−/−-POMC, and Dab1−/−-POMC mouse lines. Heterozygous reeler-POMC mice were intercrossed to obtain wild-type POMC mice; ApoER2−/−-POMC and VLDLR−/−-POMC mice were intercrossed to obtain double-knock-out mice (ApoER2−/−VLDLR−/−-POMC). Wistar rats were obtained from the animal facility of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE Microscopy Imaging Facility). In all experiments, mixed populations of female and male animals for each condition were used. Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions in the animal facility at the Center for Molecular Neurobiology Hamburg. All experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guide for animal care (license number ORG 850). Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA, as described previously (Deller et al., 1999; Overstreet et al., 2004). Experiments were performed, and the manuscript was prepared following the ARRIVE guidelines for animal research.

Immunostaining.

After decapitation, entire brains were fixed in 4% PFA followed by washing in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were embedded in 5% agarose and sectioned on a vibratome (Leica VT1000 S) at 50 μm. Slice cultures were fixed in PFA and immunostained as whole mounts. Brain sections and slice cultures were then incubated in blocking solution (5% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in 0.1 m PB), washed, and incubated in primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-Reelin G10 (1:1000, #553731, Millipore, RRID:AB_565117) and rabbit anti-Prox1 (1:1000, #AB5475, Millipore RRID:AB_177485). Tissue sections and slice cultures were washed in 0.1 m PB, incubated overnight at 4°C in appropriate secondary antibodies (AlexaFluor-568 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:300, Invitrogen; AlexaFluor-647 goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:300, Invitrogen), counterstained with DAPI, and mounted in Dako Fluorescence Mounting Medium. Tissue sections were imaged with an Olympus laser scanning microscope. The numbers of Reelin-positive CR cells in the suprapyramidal and infrapyramidal blades were determined in sections that had been randomly chosen from 7 wild-type mice (4 female and 3 male mice).

Preparation of hippocampal slice cultures.

Mice at postnatal days 0 (P0) or/and 6 (P6) as well as rats at P6 were used for the preparation of hippocampal slice cultures. Mice or rat pups were decapitated, the brains were removed, and the hippocampi were dissected and sliced (300 μm) perpendicularly to the longitudinal axis of the hippocampus on a McIlwain tissue chopper as described previously (Zhao et al., 2004). The slices were placed onto Millipore membranes (#PICM0RG50, Millicell), and each membrane was incubated in 1 ml of nutrition medium containing 25% heat-inactivated horse serum, 25% HBSS (Invitrogen), 50% minimal essential medium, 2 mm glutamine, pH 7.2 (1 ml of nutrition medium per well of a 6-well plate). Slices were incubated as static cultures in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for 4 h before live imaging started. For the coculture experiments aimed at rescuing the reeler phenotype, hippocampal slice cultures from wild-type mice (P6) or rats (P6) were cocultured to reeler-POMC hippocampal slices such that the dentate area of the reeler-POMC slice was placed next to the infrapyramidal blade of the wild-type slice (see Fig. 4A). Compared with P0, there were numerous Reelin-expressing CR cells in the infrapyramidal blades in both species at P6. No differences were observed when P6 rat or wild-type mice slices were used in these rescue experiments. For control, reeler slices were placed next to reeler slices to study potential Reelin-independent rescue effects of the coculture.

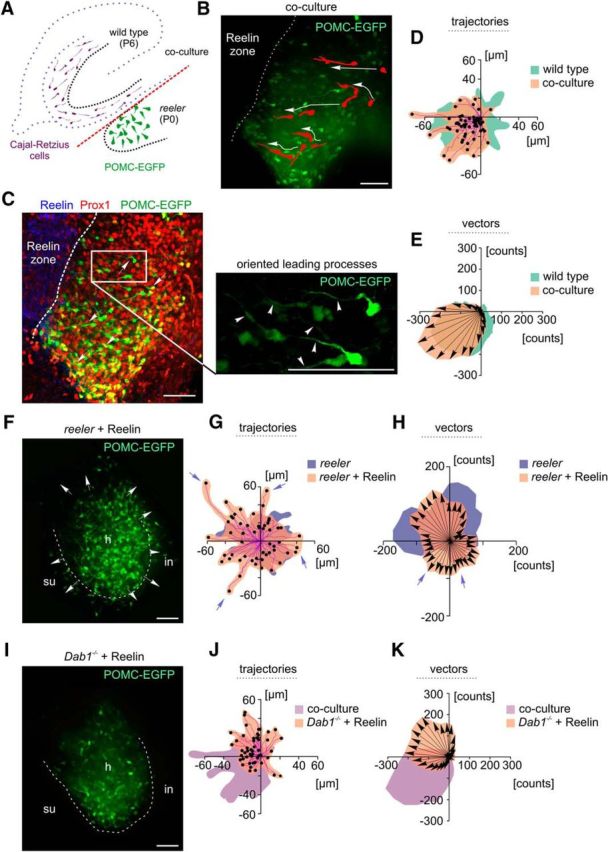

Figure 4.

Redirecting migrating reeler neurons by normotopic and ectopic, ubiquitous presentation of a Reelin source. A, Schematic representation of the coculture approach used in the present study. A wild-type hippocampal slice from a P6 animal was cocultured to a newborn (P0) reeler hippocampal slice to provide the reeler dentate gyrus with a Reelin-containing zone (CR cells, violet) in normal topographical position. B, Coculture experiment: initial positions of five migrating granule cells in the reeler dentate area and their migratory routes (large white arrows) toward the border with the wild-type culture (dashed white line) are indicated. Note the reorientation of the leading processes of the cells toward the Reelin-containing zone. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, Same coculture after fixation and staining for Reelin and Prox1. White arrows indicate neurons at their final positions after live imaging. White rectangle represents high magnification of neurons with leading processes (arrowheads) oriented toward the Reelin front. Scale bars, 50 μm. D, E, Analysis of trajectories and vector counts. Granule cells migrated directly toward the Reelin-containing zone provided by the outer molecular layer of the cocultured dentate gyrus. The cells migrated toward the infrapyramidal blade of the P6 wild-type culture, which at this postnatal stage contains many CR cells (for a long-term rescue, see also Movie 3). F, A reeler hippocampal slice culture exposed to recombinant Reelin in the medium. Arrows indicate multidirectional migration of reeler dentate cells. Reeler neurons were scattered all over the hilus (h) and invaded the molecular layer (white dashed line) of the suprapyramidal (su) and infrapyramidal (in) blades. Scale bar, 50 μm. G, H, Analysis of trajectories and vector counts. After treatment with recombinant Reelin, granule cells migrated randomly in all quadrants with longer trajectories and partially higher value counts of the migration vectors (violet arrows) than untreated reeler neurons. I–K, In contrast to reeler, the migration of Dab1−/− neurons was not stimulated after addition of recombinant Reelin, and many cells remained in the hilar region. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Treatment of hippocampal slice cultures and primary cortex neurons with recombinant Reelin, homogenate preparation, and immunoblot analysis.

HEK293 cells expressing full-length Reelin (Förster et al., 2002) or GFP (for control) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 mg/ml of the antibiotic G418 (Förster et al., 2002). After 2 d of incubation, the medium was replaced by a serum-free surrogate for an additional 3 d, and the supernatants of the Reelin-expressing cells as well as the GFP-expressing cells were then collected separately and centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min. The activity of the recombinant Reelin was confirmed in an in vitro assay using primary cerebral cortex neurons (Chai et al., 2009).

To obtain primary cortex neurons, cerebral cortices were dissected from embryonic C57BL/6 brains (embryonic day 16) and incubated in 0.025% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS at 37°C for 30 min. The tissue was then incubated in HBSS containing 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% w/v trypsin inhibitor (T-6522, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 5 min. After washing in HBSS, the tissue was triturated with a pipette tip, and the dissociated neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B-27, 0.5 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at a density of 1.7 × 106 cells per well of a 6-well plate coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 h, neurons were stimulated with recombinant Reelin for 15 min and immediately lysed in M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (#78501, ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (#78425, ThermoFisher Scientific; and #P2850, #P5726 Sigma-Aldrich, respectively) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cell lysates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Freshly prepared slice cultures were incubated in either Reelin-containing medium or control medium derived from GFP-expressing cells and imaged for 12 h. For homogenate preparations, the dentate gyri of interest from the treated hippocampal slices were excised and homogenized in lysis buffer containing 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (Carl Roth), 12 mm magnesium acetate tetrahydrate (Merck), and 6 m urea (Sigma-Aldrich) under several freezing-refreezing rounds in liquid nitrogen. The homogenates were subjected to immunoblot analysis for Reelin. Before immunoblot analysis for phosphorylated Dab1 and total Dab1, the homogenates were additionally precleared on HiTrap heparin Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 24 h.

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (Chai et al., 2009) using primary antibodies for Reelin (G10), phosphotyrosine (pY, mouse, #05-321MG, Millipore, RRID:AB_568857), Dab1 (rabbit, #AB5840, Millipore, RRID:AB_2261451), and actin (rabbit, #A2066, Sigma-Aldrich, RRID:AB_476693) in a dilution of 1:1000. HRP-coupled secondary antibodies from the corresponding species (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used in a dilution of 1:10,000. For chemoluminescence detection, the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (#34094, ThermoFisher Scientific) or a mixture of buffer A (0.5 mm luminol, 0.18 mm p-coumaric acid, 200 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.3) and buffer B (0.02% H2O2, 0.1 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.3) in a ratio of 1:1 was used. Detection was performed on the Intas Detection Apparatus (Science Imaging) using the manufacturer's software. For densitometric quantifications, the immunoblot images were processed with the ImageJ software using the macro for immunoblot quantifications.

Real-time microscopy.

All recordings for the quantitative analyses were performed with an Improvision spinning disk microscope (Carl Zeiss; PerkinElmer) equipped with a 488 nm scanning laser and two chambers (inner and outer chamber, saturated humidity, 37°C, 5% CO2). For imaging, a 20× objective lens (numerical aperture: 0.5; immersion medium: air) was used. Time-lapse images were collected every 7 min for >12 h. Photobleaching during imaging was prevented by minimizing laser power; initial image processing was performed with Volocity version 6.1.1 (PerkinElmer). Alternatively, a multiphoton laser scanning upright microscope (FV1000 MPE, BX61WI, Olympus) equipped with a Mai Tai HP laser unit (Spectra-Physics; laser wave length used: 930 nm), a Bold Line top stage incubating chamber (H301-EC-UP-BL, Okolab), and a Bold Line heating system (H301-T-UNIT, Okolab) were used with the slice cultures immersed in ACSF. Recordings were made with an ultra 25× MPE water-immersion objective (numerical aperture = 1.05) or a LUMPLFLN 60× water-immersion objective (numerical aperture = 1.0).

Neuronal tracking.

The Imaris and ImageJ software were used for neuronal tracking and for measurements of migratory speed and cell displacement. For the cells from each genotype and for the cells in the rescue experiments, at least three time-lapse recordings, lasting from 7 to >40 h, were used for the calculations. The data from the various cells of each slice culture of the same genotype were merged for final trajectory plots. For quantification of the movement of individual neurons over time, the “Manual Tracking” plugin (Fabrice Cordelières, Institut Curie, Orsay, France) with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) was used. The migratory trajectories of the neurons were visualized in the form of trajectory plots, beginning at the starting position (i.e., at the beginning of recording) and ending at the position where the cells had arrived at the end of recording. For this, we used the “Chemotaxis and Migration Tool” (ibidi, version 2.0). Based on the data of migratory trajectories, the directionalities of migrating neurons were calculated and shown providing angle positions (migration angle relative to the x axis) and neuron counts (for details, see Chemotaxis and Migration Tool, ibidi, version 1.1). Somal speed and displacement were monitored as described by Nadarajah et al. (2001).

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

The sample size (number of mice) required for a reliable statistic conclusion for each experiment in this study was iteratively estimated using the G*Power Software (Düsseldorf), assuming an a priori Type I error α = 0.05 and aiming at a Cohen effect d ≥ 0.2. For all experiments, mixed populations of female and male mice per condition were used and samples were randomly chosen. All measurements were performed with the investigator blinded to the experimental condition. Results were expressed as mean ± SD, and statistics were performed with the statistical software package Prism (GraphPad) wherever applicable. For the trajectory and vector analyses, cell sampling was randomly performed using at least 5 animals per condition. The distribution of the trajectory and vector counts in each quadrant of the R2-Euqlidean space was used as parameter for comparison between conditions. These data were collected from time-lapse imaging of migratory trajectories and represent a class of circular data, which lie between linear and spherical data and require methods of “directional statistics” (Fisher, 1993; Mardia and Jupp, 2000), standard methods for the analysis of univariate or multivariate measurements cannot be applied.

Results

Expression of POMC-EGFP allows for an analysis of migratory trajectories of wild-type and mutant granule cells

To study the trajectories of individual migrating granule cells in the developing dentate gyrus, we used hippocampal slice cultures from newborn animals expressing POMC-EGFP (Overstreet et al., 2004) defined here as wild-type with respect to Reelin signaling molecules. POMC-EGFP is mainly found in newly generated immature granule cells (Overstreet et al., 2004), which only form a fraction of a cell population positive for the homeobox gene Prox1 expressed by progenitor cells in the hilus and both immature and mature granule cells (Lavado et al., 2010). POMC-EGFP expression was sufficiently discrete to allow monitoring of individual migrating neurons and their leading and trailing processes against an unstained, dark background.

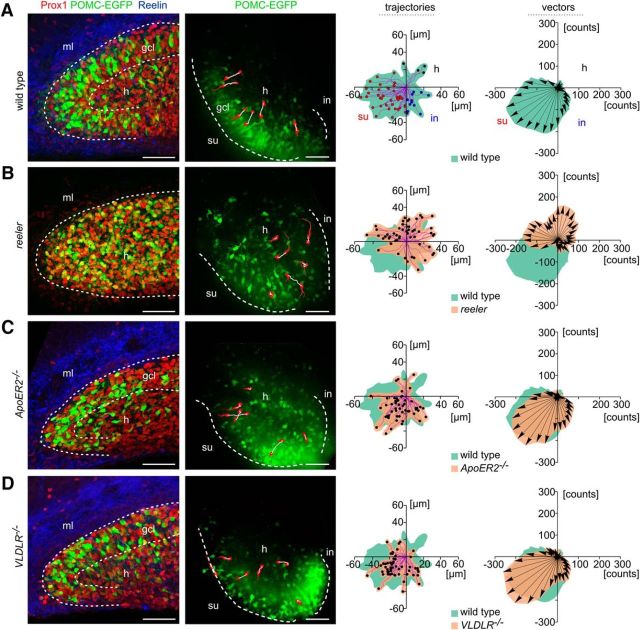

When studying the trajectories and the migratory vectors of altogether 53 POMC-EGFP-expressing neurons in wild-type slice cultures, we noticed a preferential migration directed toward the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 1A; Movie 1). It is well established that the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus develops before the infrapyramidal blade (Frotscher and Seress, 2007). Indeed, we regularly observed that the outer portion of the molecular layer of the suprapyramidal blade contained many Reelin-synthesizing CR cells, which, in contrast, were very rare in the infrapyramidal blade at this stage (P0; Fig. 1A). Indeed, the number of Reelin-positive CR cells was significantly higher in the suprapyramidal blade compared with the infrapyramidal blade (105 ± 49 cells vs 32 ± 11 cells, p = 0.0156; n = 7 wild-type mice; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test), suggesting that CR cells and Reelin, respectively, are involved in the early formation of the suprapyramidal granule cell layer, likely by attracting the granule cells.

Figure 1.

Migration of newborn granule cells in the wild-type (wt) dentate gyrus compared with mutants with deficient Reelin signaling. A, Left, Immunostaining for Reelin (blue) revealed Reelin-expressing CR cells in the molecular layer (ml), mainly of the suprapyramidal blade. Immature POMC-EGFP-expressing granule cells (green) from the hilus (h) accumulated in the developing granule cell layer (gcl). Many more neurons were positive for Prox1 (red). Right, Real-time microscopy of POMC-EGFP-labeled granule cells migrating from the hilar region toward the granule cell layer in a hippocampal slice culture. The migratory routes of six selected POMC-EGFP granule cells are indicated: red represents initial and end positions; white represents trajectories. See also Movie 1. su, Suprapyramidal blades; in, infrapyramidal blades. Analysis of trajectories in R2-Euclidean space. Diagrams, Red dots indicate granule cells reaching the suprapyramidal blade (su). Blue dots indicate cells migrating toward the infrapyramidal blade (in). Black dots indicate cells migrating toward the hilus (h) and/or CA3. Violet represents trajectories. POMC-EGFP-expressing granule cells migrated preferentially toward the suprapyramidal blade. Vector analysis showed direction (arrows) and magnitude (integrated green area) of neuronal migration. Highest vector integral counts were found in the third quadrant, where cells had migrated toward the suprapyramidal blade. B, In reeler, the dentate granule cells were dispersed all over the hilus and invaded the inner portion of the molecular layer; a compact granule cell layer was missing (see also Movie 2). In contrast to wild-type neurons, highest vector and trajectory integral counts of reeler neurons were found in the first and second quadrants. C, In ApoER2−/− mutants, many granule cells remained in the hilus with short migratory trajectories. D, In slice cultures from VLDLR−/− mice, numerous granule cells migrated normally toward the granule cell layer and occasionally “overmigrated” to the molecular layer or moved horizontally along the border between the granule cell and molecular layers. C, D, Analysis of trajectories and vector integrals indicated that the two Reelin receptors compensated for each other to some extent. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Movie 1.

Migration of wild-type dentate granule cells. Newborn granule cells (green) migrate from the hilus toward the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus to form a granule cell layer. Circles represent cells protruding into the emerging layer. The development of the suprapyramidal blade precedes that of the infrapyramidal blade.

In reeler, POMC-EGFP-expressing and Prox1-immunoreactive cells were scattered all over the hilus and did not form a distinct granule cell layer (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the trajectories of migrating granule cells in slice cultures (P0) from reeler (Fig. 1B), ApoER2/VLDLR double knock-out mice, and Dab1−/− mutants (data not shown) were in sharp contrast to those seen in animals that were wild-type with respect to Reelin-signaling molecules. There was no preferential migration toward the granule cell layer of the suprapyramidal blade. In contrast, the granule cells rather moved in all directions, traversing the hilus or migrating toward hippocampal region CA3 (Movie 2). Thus, POMC-EGFP granule cells in these mutants could migrate properly by extending a normal leading process followed by a nuclear translocation, but there was no preferred migratory direction. In addition to the cells migrating in various directions, we also observed “quiescent” cells that moved very little. Of note, the preferential migration of granule cells toward the suprapyramidal blade in ApoER2−/− or VLDLR−/− mutants was retained to a large extent (Fig. 1C,D), confirming the notion that the receptors compensated for each other, at least in part. However, we also noticed differences between the single-receptor mutants. While many granule cells in VLDLR−/− mice migrated normally toward the granule cell layer and occasionally even “overmigrated” to the molecular layer or moved horizontally along the border between the granule cell layer and molecular layer, many EGFP-labeled granule cells in ApoER2−/− cultures remained in the hilus. Together, wild-type granule cells in slice cultures of newborn animals showed a clear preference to migrate from the hilus toward the granule cell layer, particularly toward its suprapyramidal blade, whereas no preferred migration trajectories were observed in slices from reeler, ApoER2/VLDLR double knock-out mice, and Dab1−/− mutants.

Movie 2.

Migration of reeler dentate granule cells. Newborn reeler granule cells (green) form branches at multiple sites and do not show a preferred direction of movement. reeler granule cells are misplaced and spread all over the dentate area.

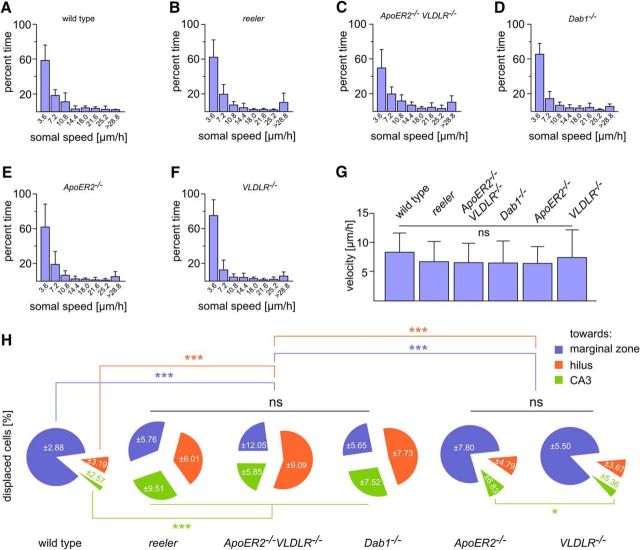

Reelin controls migration directionality, but not the migratory process or its speed

Next, we measured the somal speed of individual granule cells from wild-type animals and mutants with defect Reelin signaling (n > 10 per genotype; Fig. 2A–F). In wild-type neurons, we observed that periods of relatively rapid migration up to 30 μm/h were regularly followed by periods of arrest. Similar observations were made when the actual displacement of the cells was monitored. However, phases of relatively rapid somal speed (>30 μm/h) were rare compared with a slow migration of 0–7.2 μm/h (Fig. 2A). It was a general observation that the somal speed of individual neurons in cultures from both wild-type animals and mutants varied to a large extent (Fig. 2A–F). However, when rapid and slow phases were compared between genotypes, no significant differences were observed. Similarly, the mean velocity of many cells (n > 80 per genotype) was not significantly different, although the mutant cells tended to be slower (Fig. 2G). While almost 80% of POMC-EGFP granule cells in wild-type mice migrated from the hilus toward the Reelin-containing marginal zone, thereby forming the granule cell layer, only a minority of the granule cells in reeler, ApoER2/VLDLR double knock-out mice, and Dab1−/− mutants chose this direction, and many cells extended a leading process and migrated toward the deep hilus or CA3. Minor differences to wild-type cells were observed in granule cells from single-receptor mutants (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, we could visualize three modes of granule cell migration in slices from newborn animals, consistently to previous findings (Seki et al., 2007), radially and tangentially migrating cells as well as a tangential migration, which was converted to a radial migration (Fig. 3A–C). Extension and retraction of leading processes were similarly observed in slice cultures from reeler. However, while de novo formation or reorientation of the leading processes in wild-type animals eventually led to radial migration toward the granule cell layer, new or reoriented leading processes in reeler slices pointed in various directions (Fig. 3D,E). Often, reeler neurons branched at multiple sites and retracted their processes (Fig. 3E).

Figure 2.

Migration speed of POMC-EGFP granule cells in slice cultures from wild-type animals and mutants with deficient Reelin signaling. A–F, Frequency distribution of somal speed of >10 granule cells per genotype (mean ± SD) in slice cultures from wild-type mice (A), reeler (B), ApoER2/VLDLR double knock-out mice (C), Dab1−/− (D), ApoER2−/− (E), and VLDLR−/− mutants (F). G, Migratory speed of POMC-EGFP granule cells in slice cultures of the different genotypes; data are mean ± SD. n = 80 (wild-type cells); n = 80 (reeler cells); n = 82 (ApoER2/VLDLR double knock-out cells); n = 82 (Dab1−/− cells); n = 91 (ApoER2−/− cells); n = 84 (VLDLR−/− cells). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test with α = 0.01; five independent experiments per genotype were evaluated. H, Percentage (mean ± SD) of POMC-EGFP granule cells in wild-type and mutant cultures migrating toward the marginal zone (outer molecular layer) of the dentate gyrus, hilus, and hippocampal region CA3. A–H, Mixed populations of female and male mice per each condition were used.

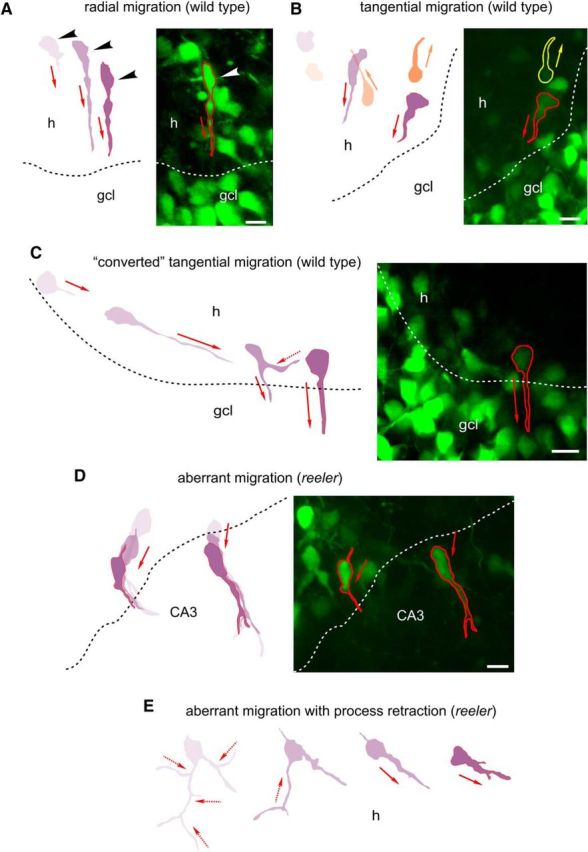

Figure 3.

Migration modes of wild-type and reeler dentate granule cells. A, Right, Radial migration of a wild-type POMC-EGFP granule cell (red contours indicate final positions) from the hilus (h) toward the granule cell layer (gcl). Left, Diagram represents migrating neurons at selected time points. Arrowheads indicate the positions of the cell soma. Red arrows indicate extension of leading processes and migratory direction. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, Tangential migration of two wild-type POMC-EGFP granule cells (red and yellow contours) in parallel to the gcl. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, “Converted” tangential migration of a wild-type granule cell. Red arrows indicate extension of leading processes and migratory direction. Dashed red arrow indicates retraction of a former leading process. Scale bar, 10 μm. D, Misorientation of leading processes and aberrant migration of POMC-EGFP neurons toward the CA3 in reeler slices. Scale bar, 10 μm. E, Reeler dentate granule cells branched at multiple sites and retracted their processes (dashed red lines) while migrating to the hilus.

Together, in granule cells from different mouse mutants with defect Reelin signaling, the directed migration toward the granule cell layer was compromised to varying degrees, which was not caused by an inability of the mutant cells to extend a leading process and move by nuclear translocation but resulted from the lack of an orientation signal provided by Reelin in the marginal zone of the dentate gyrus. This conclusion could not be drawn from a mere description of the distribution of the granule cells seen in fixed tissue sections but required imaging of the actual migratory process.

Rescue of migration directionality in reeler slices by Reelin

We have previously reported that the formation of a granule cell layer could be partially rescued in reeler slices by coculturing them with wild-type tissue containing Reelin (Zhao et al., 2004). However, in that study, we documented the final result of a coculturing experiment, yet we were unable to visualize the actual rescue process. To address this issue, we cocultured Reelin-containing hippocampal slices from P6 rats or mice next to P0 reeler slices to visualize the migration of POMC-EGFP-expressing reeler granule cells in response to the Reelin source from the adjacent coculture (Fig. 4A–C). Of note, under these coculture conditions, a Reelin zone was provided by the infrapyramidal blade of the rat or wild-type mouse dentate gyrus, which at this postnatal stage (P6) contained abundant Reelin-synthesizing CR cells and was in direct contact with the scattered granule cells of the P0 reeler culture. Many reeler granule cells needed a defined response reaction time for their migration at the initial phase of the coculture experiment. This “response reaction” preceded the de novo formation or reorientation of leading processes toward the Reelin source in the wild-type slice (Fig. 4B). As a result, many POMC-EGFP neurons eventually migrated toward the infrapyramidal blade of the wild-type culture (Fig. 4B–E). As a result of coculturing, we observed an increasing accumulation of POMC-EGFP granule cells near the Reelin source and the formation of a compact granule cell layer in the reeler culture over time (Movie 3). Of note, under coculture conditions, we observed a significant increase in the maximal velocity of migrating neurons compared with the maximal velocity of granule cells in single reeler cultures (mean ± SD, coculture: 41.16 ± 20.25 μm/h, 30 cells; single reeler culture: 27.71 ± 11.61 μm/h, 33 cells; p = 0.0066; Mann–Whitney test), likely due to an overexpression of other components of the Reelin signaling cascade in the reeler slice. The majority of the cells migrated with maximal speed toward the Reelin source after an incubation period of 9–16 h following coculturing. When we cocultured a reeler slice next to another reeler slice, no rescue of a granule cell layer was observed (data not shown), thus precluding other Reelin-independent attractive effects of the coculture.

Movie 3.

Formation of a granule cell layer in a long-term coculture. *Reelin-containing zone. gcl, Developing granule cell layer.

We then monitored neurons in reeler hippocampal slices incubated in medium containing recombinant Reelin (Förster et al., 2002) (see Materials and Methods) comparatively to Dab1−/− mutants treated with recombinant Reelin. We observed spontaneous migration of reeler POMC-EGFP-expressing granule cells, which gave rise to leading processes in various directions as a response to the Reelin treatment. However, this reeler granule cell migration did not result in the formation of a compact granule cell layer (Fig. 4F–H). Moreover, many granule cells migrated beyond the borders of the dentate area, reminiscent of the “overmigration” of granule cells in reeler mice (Zhao et al., 2003). Analysis of trajectories and vector integrals confirmed random migration in all quadrants (Fig. 4G,H). It is noteworthy that recombinant Reelin treatment did not affect the granule cell migration in Dab1−/− (Fig. 4I–K), suggesting that the promoted migration of dentate granule cells requires Reelin-induced Dab1 phosphorylation. It was deemed therefore desirable to us to test whether the recombinant Reelin added to the reeler slices was active and in sufficient amounts to induce Dab1 phosphorylation.

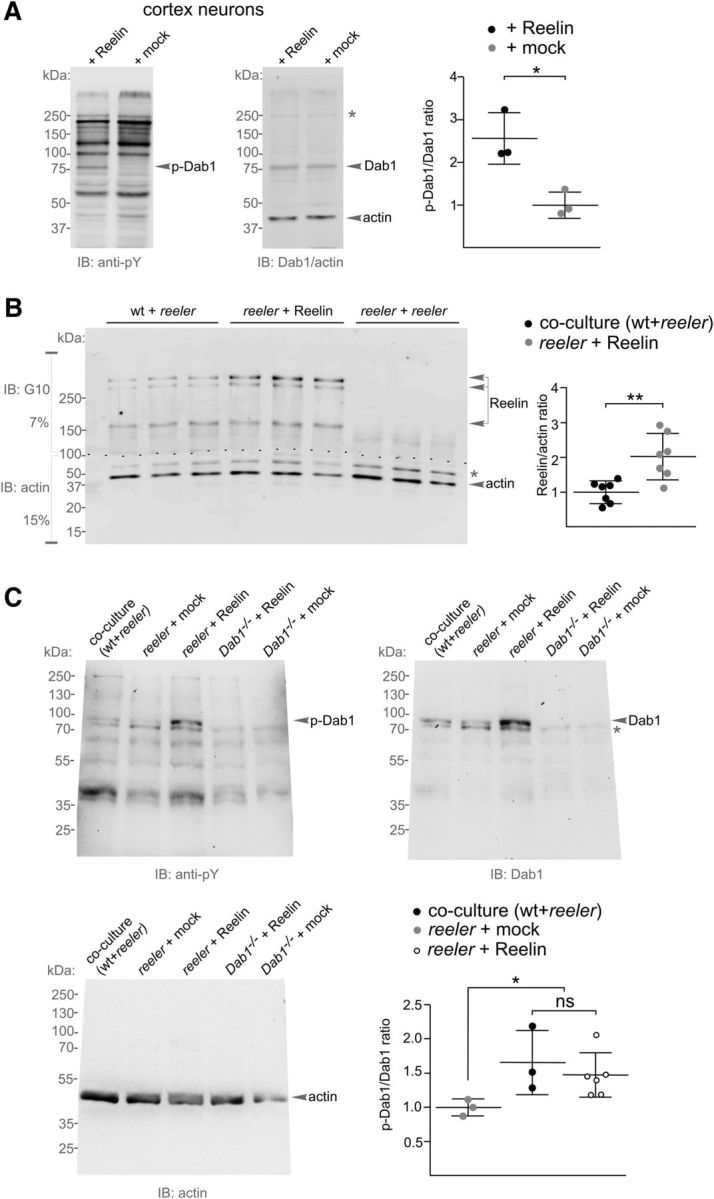

We first confirmed the induction of Dab1 phosphorylation by recombinant Reelin on a reported cell-based in vitro assay (Howell et al., 1999; Jakob et al., 2017) using cultured embryonic primary cortex neurons exposed to Reelin or mock treatment (Fig. 5A). We then subjected homogenates of reeler dentate gyri from hippocampal slices that had been treated with Reelin or cocultured to wild-type tissue to immunoblot analysis for Reelin. Homogenized gyri from reeler-reeler cocultures served as a negative Reelin control. Reelin amounts were detected in reeler gyri after coculturing with the wild-type tissue and after Reelin treatment compared with the negative reeler-reeler coculture control (Fig. 5B). Of note, the Reelin levels detected in the reeler dentate gyri after Reelin treatment were found to be higher than the levels of Reelin provided to the reeler gyrus in a coculture with wild-type tissue (Fig. 5B). To test whether Reelin that was provided to the reeler granule cells of the dentate gyrus by coculturing or by an ectopic administration induces phosphorylation of Dab1, we subjected dentate gyrus homogenates from reeler hippocampal slices, which had been cocultured with wild-type tissue, treated with Reelin, or mock-treated with a culture medium devoid of Reelin to immunoblot analysis using an antibody recognizing phosphotyrosine and a Dab1-antibody. Mock-treated and Reelin-treated Dab1−/− dentate gyrus homogenates served as negative controls. The levels of phosphorylated Dab1 were increased in reeler gyri from hippocampi cocultured to wild-type tissue or treated with recombinant Reelin compared with the levels seen in mock-treated reeler and the negative Dab1−/− controls (Fig. 5C). These findings suggested that the Reelin protein, which was provided to reeler hippocampal slices by a cocultured wild-type source or ectopic administration, penetrates the reeler dentate gyrus and acts to induce Dab1 phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

Recombinant Reelin induces Dab1 phosphorylation in reeler. A, Immunoblot analysis for phosphotyrosine (anti-pY, corresponding bands for phosphorylated Dab1 are indicated as p-Dab1) and total Dab1 expression levels in lysates from embryonic primary cortex neurons after treatment with recombinant Reelin compared with mock-treated neurons. An actin antibody was used to control loading. Molecular weights are indicated in kDa. Gray asterisk indicates nonspecific Dab1 bands. Densitometric quantification showed increased phosphorylation of Dab1 after Reelin treatment. p-Dab1/Dab1 intensity ratios were normalized on the mock condition and the actin signal, and are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p = 0.028 (parametric unpaired two-tailed t test with Welch's correction). B, Immunoblot analysis of Reelin expression levels in homogenized reeler dentate gyri after coculture with wild-type tissue or treatment with recombinant Reelin or in coculture to another reeler slice; three representative samples for each condition are shown. Reelin was detected in a 7% gel (top), actin in a 15% gel (bottom). After Reelin detection, the membrane was cut (dashed line) and the lower membrane part was used for actin detection. Gray asterisk indicates nonspecific bands. Densitometric quantification showing Reelin/actin intensity ratios normalized on the coculture (wt + reeler) condition presents mean ± SD from seven independent experiments. **p = 0.007 (unpaired two-tailed t test with nonparametric Mann–Whitney comparison). C, Immunoblot analysis for phosphotyrosine (pY, corresponding bands for phosphorylated Dab1 are indicated as p-Dab1), Dab1, and actin expression levels in homogenized and heparin-precleared reeler dentate gyri after coculture with wild-type tissue, or treatment with recombinant Reelin or a mock solution. Reelin- and mock-treated Dab1−/− dentate gyrus homogenates served as negative controls. Gray asterisk indicates nonspecific Dab1 bands. Densitometric quantifications showed increased phosphorylation of Dab1 after Reelin treatment. p-Dab1/Dab1 intensity ratios were normalized on the condition of mock-treated reeler and the actin signal, and are presented as mean ± SD. *p = 0.014 (one-way ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis test).

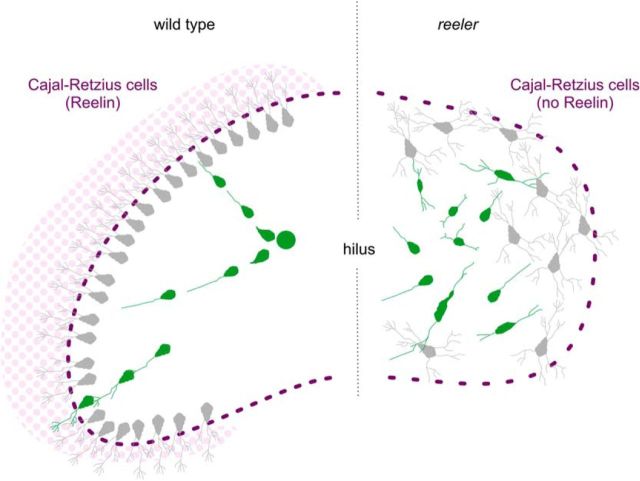

However, the combined results from our coculture experiments indicated that, only if the Reelin source is topographically arranged, the migration of newly generated granule cells is directed in such a way to eventually result in a compact granule cell layer formation and, thus, to contribute to the lamination of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Summary diagram illustrating Reelin-dependent directed migration of POMC-EGFP granule cells toward the granule cell layer in the dentate gyrus of wild-type mice and aberrant migration in the dentate area of reeler. Green cells represent POMC-EGFP-expressing, migrating granule cells. Gray cells represent postmigratory granule cells having lost their POMC-EGFP expression. In the wild-type culture, the migratory route of an example granule cell from the hilus to its arrival position in the granule cell layer (green neuron) is shown. As the cell continues its development by additional branching, the EGFP expression decreases. In contrast to the directed migration in the wild-type dentate gyrus, POMC-EGFP-expressing migrating reeler granule cells move in various directions, and postmigratory neurons do not form a compact cell layer, but they are scattered all over the dentate area.

Discussion

By visualizing the trajectories of newly generated, migrating granule cells in tissue from wild-type animals and mouse mutants deficient in molecules of the Reelin signaling cascade, our results show that Reelin exerts an attractive effect, controlling migration directionality of these neurons. In slice cultures from newborn wild-type animals, we observed preferential migration toward the Reelin-containing marginal zone of the suprapyramidal blade but not toward the infrapyramidal blade, which is yet poorly developed and almost devoid of CR cells at that stage. In mutants lacking Reelin or its signaling molecules, no such directed migration was observed, although the granule cells were able to migrate with similar speed by extending a leading and trailing process and translocating their nuclei. Moreover, directed migration toward a Reelin source was induced in granule cells of reeler cultures cocultured to a wild-type slice providing Reelin in normal topographical position, but was not observed when reeler slices were incubated with medium containing recombinant Reelin.

Neurons in slice cultures are expected to move in the 3D space. We figured out that migration along the z axis was minimal compared with x and y directions and, thus, used software for an analysis of 2D movements as an approximation (see Materials and Methods). However, we cannot exclude that we are faced here with a limitation of the slice preparation. For an analysis of directionality, data were generated by collecting the number of migrating neurons in the different sectors as “counts” and illustrating the distribution of migratory directions (Fisher, 1993; Semmling et al., 2010). This approach allowed us to determine migration vectors in wild-type mice and aberrant vectors in the various mutants of the Reelin signaling pathway.

Reelin is an attractive signal for migrating granule cells of the dentate gyrus

Here, we provide direct evidence for Reelin being an attractive signal for migrating neurons in the murine dentate gyrus. First, we have shown that POMC-EGFP expression around birth reliably labeled migrating granule cells, which enabled us to trace their trajectories. We observed that, in wild-type cultures, granule cells preferentially migrated toward the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus, which in mice is well developed at this stage and contains abundant Reelin-synthesizing CR cells in its marginal zone, the outer molecular layer. This is in sharp contrast to the yet poorly developed infrapyramidal blade, forming mainly in the early postnatal period (Frotscher and Seress, 2007). We have reason to assume that Reelin is involved in the directionality of the migration process because granule cells in cultures deficient in Reelin-signaling molecules did not show this preferential migration and rather migrated toward the hilus and CA3, respectively. Moreover, granule cells in reeler cultures migrated toward the infrapyramidal blade of cocultured wild-type dentate gyrus from postnatal day 6, providing abundant Reelin in a position similar to the normal outer molecular layer. When reeler granule cells cocultured to wild-type tissue were analyzed over time, they eventually developed a compact granule cell layer underneath the wild-type outer molecular layer. Formation of a granule cell layer did not occur when two reeler slices were cocultured. This particular experimental design confirmed that it is Reelin, and not some unknown factor in the suprapyramidal blade, that attracts migrating granule cells in wild-type cultures from P0.

We regard it as a major finding of the present study that deficient Reelin signaling did not interfere with the actual migration process. Thus, somal speed, translocation of the nucleus, and displacement were not found to be significantly different between migrating wild-type neurons and neurons deficient in Reelin receptors or Dab1. Recent studies have shown that spatiotemporal dynamics of traction forces depending on myosin-II were associated with somal translocation in migrating neurons (He et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2015) in addition to proneural transcription factors regulating RhoA signaling (Pacary et al., 2011). While somal translocation appeared to be normal in reeler mutants, double-receptor mutants, and Dab1-deficient mice, the directionality of migration was significantly altered. Single-receptor mutants showed almost normal migration directions, indicating that ApoER2 and VLDLR can compensate each other to some extent (Hack et al., 2007). Additional evidence for Reelin's role in determining the direction of migration comes from an analysis of migration modes. In addition to radial migration toward the granule cell layer, we observed that horizontally migrating cells “corrected” their migratory route by retracting their horizontal leading process and forming a secondary radial leading process toward the granule cell layer. Similarly, in our coculture experiments, we noticed that the granule cells migrated toward the Reelin source following a “response reaction” by withdrawing the original leading process and forming a new radially oriented one, by reorienting the original leading process or by giving rise to a new branch. In all cases, the result was a directed migration toward the Reelin source in the cocultured wild-type slice. We hypothesize that the significantly increased maximal velocity of migrating reeler granule cells under coculture conditions might have been caused by an overexpression of Reelin receptors in the absence of the ligand, but further studies are required to confirm this assumption. Together, the results indicate that Reelin in specific topographical location is an attractive factor for the orientation of the leading processes of neurons and for directed neuronal migration. Application of recombinant Reelin to the culture medium, which does not provide a Reelin source in a circumscribed location, was unable to correct directed granule cell migration, but it promoted Dab1 phosphorylation. However, in a stripe-choice assay, recombinant Reelin was shown to affect process orientation and branching (Förster et al., 2002).

Is Reelin a stop signal for migrating granule cells?

If Reelin in the outer molecular layer is an attractive signal for migrating granule cells, why do they not invade the molecular layer? How can it be that Reelin first attracts migrating neurons and then terminates their migration? In a stripe choice assay, Reelin was observed to induce branching of the processes of radial glial cells, neuronal progenitors (Förster et al., 2002). Moreover, using in utero electroporation, we have recently shown that both radial glial fibers and the leading processes of neurons branched upon arrival in the Reelin-containing marginal zone of the developing neocortex (Chai et al., 2015). In contrast, in reeler mutants, radial glial fibers gave rise to significantly fewer branches in the marginal zone. When imaging the leading processes of migrating neurons and the formation of their branches in the marginal zone, we noticed that the branches were considerably thinner than the stem process. Nuclear translocation was regularly terminated as soon as the nucleus arrived at the branching point (Chai et al., 2015; O'Dell et al., 2015). We hypothesize that Reelin-induced branching of the leading process contributes to the termination of migratory activity, thus preventing the immigration of neurons into the molecular layer (marginal zone) of the dentate gyrus. Conversely, in reeler, branching is compromised, and the inner portion of the molecular layer is invaded by many migrating neurons (Zhao et al., 2003). Alternatively, the presence of VLDLR, but not ApoER2, in distal segments of the leading process (Hirota et al., 2015) might be crucial for neuronal arrest because, in reeler mice and VLDLR-deficient mutants, but not in ApoER2 knock-out animals, migrating neurons “overmigrate” into the marginal zone (Hack et al., 2007).

Binding of Reelin to its receptors activates Dab1 and, in turn, results in the phosphorylation of LIM kinase1, which induces phosphorylation of N-cofilin (nonmuscle cofilin) (Chai et al., 2009). Cofilin is an actin-depolymerizing protein involved in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (Arber et al., 1998; Bamburg, 1999). Phosphorylation of cofilin at serine3 renders the protein unable to depolymerize actin, thereby stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton. Both Reelin-induced branching and cytoskeletal stabilization by cofilin phosphorylation might anchor the leading processes to the marginal zone, thus being essential components of Reelin's effects on directed neuronal migration and on the termination of the migratory process. Undoubtedly, Reelin's functions are far more complex, as recent studies have shown that Reelin also acts on the microtubule plus-end binding protein CLASP2, thereby regulating extension and orientation of the leading process (Dillon et al., 2017).

In conclusion, our results suggest the following scenario: Reelin attracts the leading processes of migrating granule cells, thereby determining migration direction. Branching of the leading processes in the marginal zone together with cytoskeletal stabilization induced by cofilin phosphorylation terminates nuclear translocation and, thus, migration. This, in turn, leads to the accumulation of neurons just underneath the marginal zone and to the formation of a compact granule cell layer in wild-type animals, but not in mouse mutants deficient in Reelin signaling.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants FR 620/12-2 and FR 620/13-1 to M.F. and Grant BR4888/2-1 to B.B., the Hertie Foundation to M.F., and the China Scholarship Council to S.W. D.L. was supported by Medical Faculty, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf FFM Fellowship. We thank Dr. Joachim Herz for providing reeler mice and mutants deficient in Reelin receptors and Dab1, respectively; Dr. Irm Hermans-Borgmeyer for embryo transfer; Bettina Herde, Dagmar Drexler, Janice Graw, Dung Ludwig, and Saskia Siegel for genotyping; and Silvana Deutsch and Kristian Schacht for animal care.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P (1998) Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393:805–809. 10.1038/31729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburg JR. (1999) Proteins of the ADF/cofilin family: essential regulators of actin dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Biol 15:185–230. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Durudas A, Qiu S, Masiulis I, Sweatt JD, Li WP, Adelmann G, Frotscher M, Hammer RE, Herz J (2005) Modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory by Reelin involves differential splicing of the lipoprotein receptor Apoer2. Neuron 47:567–579. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X, Förster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M (2009) Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3. J Neurosci 29:288–299. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X, Fan L, Shao H, Lu X, Zhang W, Li J, Wang J, Chen S, Frotscher M, Zhao S (2015) Reelin induces branching of neurons and radial glial cells during corticogenesis. Cereb Cortex 25:3640–3653. 10.1093/cercor/bhu216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X, Zhao S, Fan L, Zhang W, Lu X, Shao H, Wang S, Song L, Failla AV, Zobiak B, Mannherz HG, Frotscher M (2016) Reelin and cofilin cooperate during the migration of cortical neurons: a quantitative morphological analysis. Development 143:1029–1040. 10.1242/dev.134163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T, D'Arcangelo G (1998) Role of reelin in the control of brain development. Brain Res 26:285–294. 10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00035-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T (1995) A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 374:719–723. 10.1038/374719a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T (1999) Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron 24:471–479. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80860-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río JA, Heimrich B, Borrell V, Förster E, Drakew A, Alcántara S, Nakajima K, Miyata T, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K, Derer P, Frotscher M, Soriano E (1997) A role for Cajal-Retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections. Nature 385:70–74. 10.1038/385070a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T, Drakew A, Heimrich B, Förster E, Tielsch A, Frotscher M (1999) The hippocampus of the reeler mutant mouse: fiber segregation in area CA1 depends on the position of the postsynaptic target cells. Exp Neurol 156:254–267. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon GM, Tyler WA, Omuro KC, Kambouris J, Tyminski C, Henry S, Haydar TF, Beffert U, Ho A (2017) CLASP2 links Reelin to the cytoskeleton during neocortical development. Neuron 93:1344–1358.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulabon L, Olson EC, Taglienti MG, Eisenhuth S, McGrath B, Walsh CA, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES (2000) Reelin binds alpha3beta1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron 27:33–44. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS. (1951) Two new mutants, ‘trembler’ and ‘reeler,’ with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.). J Genet 50:192–201. 10.1007/BF02996215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NI. (1993) Statistical analysis of circular data. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Förster E, Tielsch A, Saum B, Weiss KH, Johanssen C, Graus-Porta D, Müller U, Frotscher M (2002) Reelin, Disabled 1, and beta1 integrins are required for the formation of the radial glial scaffold in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:13178–13183. 10.1073/pnas.202035899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster E, Zhao S, Frotscher M (2006) Laminating the hippocampus. Nat Rev Neurosci 7:259–267. 10.1038/nrn1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco SJ, Martinez-Garay I, Gil-Sanz C, Harkins-Perry SR, Müller U (2011) Reelin regulates cadherin function via Dab1/Rap1 to control neuronal migration and lamination in the neocortex. Neuron 69:482–497. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M. (1998) Cajal-Retzius cells, Reelin, and the formation of layers. Curr Opin Neurobiol 8:570–575. 10.1016/S0959-4388(98)80082-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M. (2010) Role for Reelin in stabilizing cortical architecture. Trends Neurosci 33:407–414. 10.1016/j.tins.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M, Seress L (2007) Morphological development of the hippocampus. In: The hippocampus book (Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J, eds), pp 115–131. Oxford: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Hack I, Hellwig S, Junghans D, Brunne B, Bock HH, Zhao S, Frotscher M (2007) Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons. Development 134:3883–3891. 10.1242/dev.005447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto-Torii K, Torii M, Sarkisian MR, Bartley CM, Shen J, Radtke F, Gridley T, Sestan N, Rakic P (2008) Interaction between Reelin and Notch signaling regulates neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex. Neuron 60:273–284. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Zhang ZH, Guan CB, Xia D, Yuan XB (2010) Leading tip drives soma translocation via forward F-actin flow during neuronal migration. J Neurosci 30:10885–10898. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0240-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Kubo K, Katayama K, Honda T, Fujino T, Yamamoto TT, Nakajima K (2015) Reelin receptor ApoER2 and VLDLR are expressed in distinct spatiotemporal patterns in developing mouse cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol 523:463–478. 10.1002/cne.23691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BW, Hawkes R, Soriano P, Cooper JA (1997) Neuronal position in the developing brain is regulated by mouse disabled-1. Nature 389:733–737. 10.1038/39607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BW, Herrick TM, Cooper JA (1999) Reelin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled 1 during neuronal positioning. Genes Dev 13:643–648. 10.1101/gad.13.6.643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob B, Kochlamazashvili G, Jäpel M, Gauhar A, Bock HH, Maritzen T, Haucke V (2017) Intersectin 1 is a component of the Reelin pathway to regulate neuronal migration and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:5533–5538. 10.1073/pnas.1704447114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Zhang ZH, Yuan XB, Poo MM (2015) Spatiotemporal dynamics of traction forces show three contraction centers in migratory neurons. Cell Biol 209:759–774. 10.1083/jcb.201410068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferman JV, Basu J, Russo MJ, Guevarra J, Cheung SK, Siegelbaum SA (2014) Reelin signaling specifies the molecular identity of the pyramidal neuron distal dendritic compartment. Cell 158:1335–1347. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM (1998) The reeler mouse as a model of brain development. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 150:1–106. 10.1007/978-3-642-72257-8_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavado A, Lagutin OV, Chow LM, Baker SJ, Oliver G (2010) Prox1 is required for granule cell maturation and intermediate progenitor maintenance during brain neurogenesis. PLoS Biol 8:e1000460. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia KV, Jupp PE (2000) Directional statistics. Chichester, New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Goffinet AM (1998) Prenatal development of reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the human neocortex. J Comp Neurol 397:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah B, Brunstrom JE, Grutzendler J, Wong RO, Pearlman AL (2001) Two modes of radial migration in early development of the cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci 4:143–150. 10.1038/83967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell RS, Cameron DA, Zipfel WR, Olson EC (2015) Reelin prevents apical neurite retraction during terminal translocation and dendrite initiation. J Neurosci 35:10659–10674. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1629-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet LS, Hentges ST, Bumaschny VF, de Souza FS, Smart JL, Santangelo AM, Low MJ, Westbrook GL, Rubinstein M (2004) A transgenic marker for newly born granule cells in dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 24:3251–3259. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5173-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacary E, Heng J, Azzarelli R, Riou P, Castro D, Lebel-Potter M, Parras C, Bell DM, Ridley AJ, Parsons M, Guillemot F (2011) Proneural transcription factors regulate different steps of cortical neuron migration through Rnd-mediated inhibition of RhoA signalling. Neuron 69:1069–1084. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Caviness VS Jr (1995) Cortical development: view from neurological mutants two decades later. Neuron 14:1101–1104. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DS, Curran T (2001) Role of the reelin signaling pathway in central nervous system development. Annu Rev Neurosci 24:1005–1039. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Namba T, Mochizuki H, Onodera M (2007) Clustering, migration, and neurite formation of neural precursor cells in the adult rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol 502:275–290. 10.1002/cne.21301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmling V, Lukacs-Kornek V, Thaiss CA, Quast T, Hochheiser K, Panzer U, Rossjohn J, Perlmutter P, Cao J, Godfrey DI, Savage PB, Knolle PA, Kolanus W, Förster I, Kurts C (2010) Alternative cross-priming through CCL17-CCR4-mediated attraction of CTLs toward NKT cell-licensed DCs. Nat Immunol 11:313–320. 10.1038/ni.1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, Yoneshima H, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, Howell BW, Cooper JA, Goldowitz D, Curran T (1997) Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice. Nature 389:730–733. 10.1038/39601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibbe M, Förster E, Basak O, Taylor V, Frotscher M (2009) Reelin and Notch1 cooperate in the development of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 29:8578–8585. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0958-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F, Goffinet AM (2003) Reelin and brain development. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:496–505. 10.1038/nrn1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Herz J (1999) Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knock-out mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell 97:689–701. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80782-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware ML, Fox JW, Gonzáles JL, Davis NM, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Russo CJ, Chua SC Jr, Goffinet AM, Walsh CA (1997) Aberrant splicing of a mouse disabled homolog, mdab1, in the scrambler mouse. Neuron 19:239–249. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80936-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Frotscher M (2010) Go or stop? Divergent roles of Reelin in radial neuronal migration. Neuroscientist 16:421–434. 10.1177/1073858410367521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Förster E, Chai X, Frotscher M (2003) Different signals control laminar specificity of commissural and entorhinal fibers to the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 23:7351–7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Chai X, Förster E, Frotscher M (2004) Reelin is a positional signal for the lamination of dentate granule cells. Development 131:5117–5125. 10.1242/dev.01387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]