Abstract

Viral hepatitis, syphilis, HIV, and tuberculosis infections in prisons have been identified globally as a public health problem. Tuberculosis (TB) and viral hepatitis co-infection may increase the risk of anti-tuberculosis treatment-induced hepatotoxicity, leading to the frequent cause of discontinuation of the first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Therefore, the aim of this cross-sectional study was to investigate the epidemiological features of HCV, HBV, syphilis and HIV infections among bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis prisoners in Campo Grande (MS), Central Brazil. The participants who agreed to participate (n = 279) were interviewed and tested for the presence of active or current HCV, HBV, syphilis and HIV infections. The prevalence of HCV exposure was 4.7% (13/279; 95% CI 2.2–7.1). HCV RNA was detected in 84.6% (11/13) of anti-HCV positive samples. Out of 279 participants, 19 (6.8%; 95% CI 4.4–10.4) were HIV co-infected, 1.4% (4/279, 95% CI 0.5–3.8) had chronic hepatitis B virus (HBsAg positive) and 9.3% (26/279, 95% CI 6.4–13.4) had serological marker of exposure to hepatitis B virus (total anti-HBc positive). The prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection (anti-T. pallidum positive) was 10% (28/279, 95% CI 7.0–14.2) and active syphilis (VDRL ≥ 1/8 titre) was 5% (14/279, 95% CI 2.9–8.3). The prevalence of TB/HCV co-infection among prisoners with HIV (15.8%) was higher than among HIV-non-infected prisoners (3.8%; P<0.05). These results highlight the importance of hepatitis testing among prisoners with bacteriologically confirmed case of TB who can be more effectively and safely treated in order to reduce the side effects of hepatotoxic anti-TB drugs.

Introduction

Brazil is classified as the third country with the largest prison population in the world [1, 2]. While the other four countries that most imprisoned from 2010 to 2015 presented a reduction in the evolution of the incarceration rate, Brazil exacerbated this number along with its crime statistics. In 2015, Brazil had about 698,618 incarcerated individuals in penitentiary systems (342/100 thousand inhabitants), which are only designed to hold 371,201 [1], classified as the third country with the largest prison population in the world [1, 2]. The state of Mato Grosso do Sul (MS) in Central Brazil has the highest rate of incarceration in the country, with approximately 15,700 inmates [1].

Prisoners are a high-risk group for contracting and transmitting infectious diseases, including tuberculosis (TB), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and syphilis. This is due in part to confinement related conditions and also to greater socioeconomic disadvantage, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors within this population before, during, and after incarceration [3].

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the main causes of death due to infectious diseases. In 2016, there were 10.4 million new TB cases worldwide [4]. Globally, prisons are directly linked to high prevalence and incidence of TB morbidity and mortality of TB infection compared with other population cohorts [3]. Based on Brazilian TB notification database and incarceration data, it was found that prisons represent a growing proportion of the national TB burden [5, 6]. Although prison infrastructure and conditions vary considerably in different countries, overcrowding and poorly ventilated custodial settings are common, increasing the transmission risks of TB among prisoners [7, 8, 9]. A recent study demonstrated that during 2009–2014, tuberculosis (TB) cases among prisoners rose 28.8% [5].

Although the high-risk of active TB infection in prisoners is well known, the prevalence of HCV, HBV, and syphilis infections among them has not been widely investigated [10]. In addition, the presence of chronic liver disease caused by hepatitis C and B virus is an additive risk factor for the development of anti-TB drug-induced hepatotoxicity (DIH) during anti-TB therapy [11, 12, 13, 14]. Hepatotoxicity is a frequent cause of the discontinuation of three of the first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs [15, 16]. Unfortunately, treatment of chronic HCV and HBV infections, HIV, syphilis, and TB are often not properly administered to Brazilian prisoners because of the numerous difficulties in screening, management and follow-up. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the epidemiological features of HCV, HBV, syphilis and HIV infections in bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis prisoners in Campo Grande (MS), Central Brazil.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional survey was conducted among male prisoners with bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis in the capital city of Campo Grande, MS, Central Brazil. From May 2014 to March 2017, male prisoners were recruited from two closed penal institutions: Instituto Penal de Campo Grande (IPCG) and Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho (EPJFC). Based on the latest Census of Prison Units and Aggregate Data, published in 2016, there were approximately 3,400 inmates in these two major penal institutions, which had a capacity to house up to 904 prisoners [17].

All prisoners diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed TB by the infectious diseases specialists were included in the eligible population. Bacteriologically confirmed case of TB was defined as the presence of at least one positive smear microscopy or solid culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Of the 279 individuals that agreed to participate, 75 individuals were from IPCG (Instituto Penal de Campo Grande) and 204 were from EPJFC (Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho). Participants were informed about the survey, signed a written and informed consent, and then they were interviewed face-to-face to obtain information on sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors using a questionnaire (–S1 and S2 Files). Blood samples were collected from all participants and stored at -70°C. This survey has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, MS, Brazil (CAAE: 32447814.9.0000.0021). Participation of eligible individuals was voluntary and no compensation was provided. The available medical treatment offered to the subjects was the same regardless of whether they participated in the study or not.

All blood samples were tested for HIV (anti-HIV 1/2), HBV (HBsAg, total anti-HBc, and anti-HBs), lifetime syphilis infection (antibody to T. pallidum), and HCV (anti-HCV) serological markers using the electrochemiluminescence (ECL) analyzed in the Cobas e601 Analyser (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). ECL-reactive samples for anti-T.pallidum were serially diluted to quantify Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) titers and to determine whether the disease is active. As recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, participants were considered to have active syphilis when they presented VDRL titers equal or superior to 1/8 plus treponemal test positive [18]. All positive and indeterminate specimens for antibodies against HIV-1/2 by ECL were confirmed by Western blot assay (Novopath HIV-I, Immunoblot, BioRad).

All positive or indeterminate samples for anti-HCV were submitted to the detection of HCV RNA by Real-Time HCV assay (qPCR) (Abbott RealTime HCV) and submitted to a direct nucleotide sequencing reaction in both directions using a Big Dye Terminator kit (version 3.1, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Data processing and analysis were performed in the statistical software Stata SE, version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA). We performed the chi-square test (χ2) to determine differences between subgroups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A 2-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to serological markers of exposure to HCV, HBV, HIV and syphilis infections among 279 participants are shown in Table 1 and supporting information–minimal data (DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.8204525). The median age was 29 years. Of the total participants, 53.8% were multiracial, 59.5% had a non-steady partner and 63.8% were from MS State. The majority of participants had pulmonary TB manifestation (97.8%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to anti-HCV, total anti-HBc, anti-HIV, and anti-T.pallidum seropositivity among prisoners with bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis in Central Brazil (n = 279).

| Anti-HCV positive | Total anti-HBc positive | Anti-HIV positive | Anti-T.pallidum positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <25 years (n = 211) | 2 | 0.95 | 13 | 6.16 | 11 | 5.21 | 13 | 6.16 |

| ≥ 25 years (n = 68) | 11 | 16.18 | 13 | 19.12 | 8 | 11.8 | 15 | 22.06 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| With a steady partner (n = 113) | 3 | 2.65 | 7 | 6.19 | 4 | 3.54 | 7 | 6.19 |

| Without a steady partner (n = 166) | 10 | 6.02 | 19 | 11.45 | 15 | 9.04 | 21 | 12.65 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White (n = 73)* | 3 | 4.11 | 4 | 5.48 | 5 | 6.85 | 8 | 10.96 |

| Multiracial (n = 150) | 10 | 6.67 | 14 | 9.33 | 9 | 6.00 | 13 | 8.67 |

| Black (n = 51) | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 15.69 | 5 | 9.80 | 7 | 13.73 |

| Asian (n = 4) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Education level (years) | ||||||||

| ≤4 (n = 68) | 5 | 7.35 | 9 | 13.24 | 5 | 7.35 | 14 | 20.59 |

| ≥5 (n = 211) | 8 | 3.79 | 17 | 8.06 | 14 | 6.64 | 14 | 6.64 |

| Naturality | ||||||||

| MS (n = 178) | 10 | 5.62 | 17 | 9.55 | 10 | 5.62 | 17 | 9.55 |

| Others (n = 101) | 3 | 2.97 | 9 | 8.91 | 9 | 8.91 | 11 | 10.89 |

| Type of tuberculosis disease | ||||||||

| Pulmonary TB (n = 271) | 13 | 4.80 | 23 | 8.49 | 16 | 5.90 | 25 | 9.23 |

| Extra-pulmonary TB (n = 6) | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 2 | 33.33 |

| Penal institutions | ||||||||

| EPJFC (n = 204) | 9 | 4.41 | 19 | 9.31 | 8 | 3.92 | 18 | 8.82 |

| IPCG (n = 75) | 4 | 5.33 | 7 | 9.33 | 11 | 14.67 | 10 | 13.33 |

*Descendants of Europeans.

EPJC–Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho; IPCG–Instituto Penal de Campo Grande; TB–Tuberculosis; MS–Mato Grosso do Sul State.

The overall prevalence of HCV exposure was 4.7% (13/279, 95% CI 2.2–7.1). Among the 279 participants, 19 (6.8%; 95% CI 4.4–10.4) were HIV co-infected, 1.4% (4/279, 95% CI 0.5–3.8) had chronic hepatitis B infection (HBsAg positive) and 9.3% (26/279, 95% CI 6.4–13.4) had serological marker of exposure to hepatitis B virus infection (total anti-HBc positive). The prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection (anti-T.pallidum positive with any VDRL titres) was 10% (28/279, 95% CI 7.0–14.2) and active syphilis (VDRL ≥ 1/8 titre) was 5% (14/279, 95% CI 2.9–8.3).

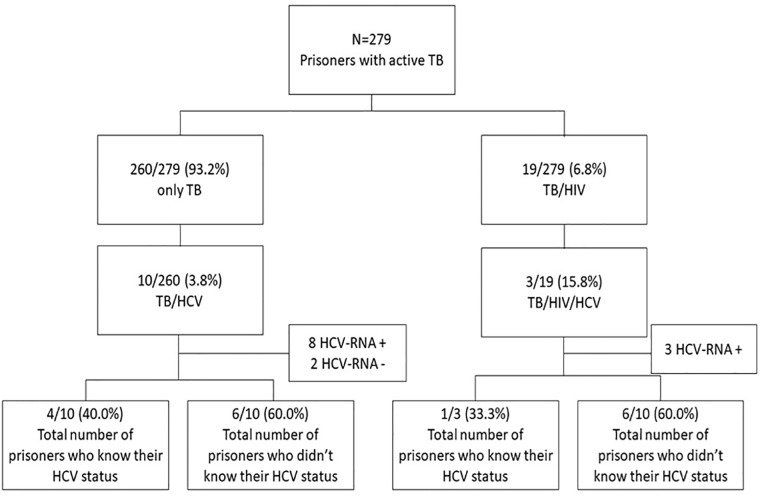

Co-infection TB/HCV prevalence among participants with HIV (15.8%) was higher than that observed in HIV-non-infected inmates (3.8%; p<0.05) (Fig 1). Among all anti-HCV positive prisoners with bacteriologically confirmed TB, 23.1% (3/13) also presented positivity for anti-HIV-1, 23.1% (3/13) for anti-Treponema pallidum, and 30.8% (4/13) had serological evidence of prior HBV exposure (total anti-HBc positive).

Fig 1. Enrollment of bacteriologically confirmed TB cases in the study.

Those with a serological marker of HCV, HBV and syphilis exposure were significantly more likely to be aged > 35 years (p<0.001; p = 0.002; p<0.001, respectively).

All anti-HIV-positive participants had access to HIV treatment, including antiretroviral therapy, care, and support. It was equivalent to that available to people living with HIV (PLWA) in the community and was in line with national guidelines. All bacteriologically confirmed TB prisoners with chronic hepatitis B infection had also access to hepatitis B treatment and tuberculosis programs, including treatment protocols [19, 20, 21]. During the study period, anti-HCV-positive participants did not receive the interferon-based HCV treatment often because all of them was not eligible for this treatment and also because of the difficulties in management and follow-up of this protocol [22]. Although benzathine penicillin is the recommended first-line treatment for syphilis in Brazil, participants with active syphilis were treated with an alternative antibiotic drug for the treatment of syphilis.

The presence of HCV RNA was detected in 11/13 (84.61%) of anti-HCV positive samples. Ten (90.9%) HCV RNA-positive samples were genotyped as genotype 1 and one (9.1%) as genotype 3.

Discussion

The high-risk environment in prisons provides optimal conditions for acquiring and transmitting infectious diseases such as HBV, HCV and HIV exposure including TB [9]. The prevention and diagnosis of these infections among bacteriologically confirmed TB prisoners require immediate attention. Therefore, infectious diseases screening may provide benefits on treatment and subsequent monitoring of these co-infections.

Tuberculosis is still the most common opportunistic infection worldwide [4], and it has been endemic especially inside Brazilians prisons [23]. Anti-HCV prevalence rates are generally higher among patients with TB than in the general population [24, 25, 26]. In 2014, it was estimated that there were around 10.2 million prisoners worldwide, 2.8% had active TB, 15.1% had HCV infection, 3.8% had HIV and 4.8% had chronic HBV [3]. The prevalence of HCV exposure found in our study (4.7%) is consistent with previous studies conducted among prisoners in Mato Grosso do Sul state which reported 4.8% and 2.4% of HCV exposure in 2011 and 2017, respectively [27, 28]. These similar prevalence rates found in different periods of time may suggest that TB remains a persistent public health problem in a prison environment regardless of the clinical TB status of the prisoners.

The HCV prevalence found in this study (4.7%; 95% CI 2.2–7.1) was higher than that observed among the general population (1.38%) and higher than that previously reported among blood donors from the same region (0.17%) [29, 30]. This prevalence was lower than that found among imprisoned people from different countries, ranging from 8% to 95% [3]. Most of these rates are normally related to injection drug use [31, 32]. These variations may reflect regional differences in the prevalence of HCV infection and also could be explained by the low number of people who inject drugs (PWID) among Brazilian prisoners [23, 28]. In fact, PWID are more likely to be infected with HCV than non-PWID [25, 32].

Diagnosis of HIV seropositivity during the screening of tuberculosis is common [33]. In addition, among the HIV infected person, HCV co-infection is more prevalent due to overlapping transmission routes (sexual, parenteral and vertical) [34]. The prevalence of HCV infection was 4 times higher in TB/HIV-co-infected patients than in patients infected with TB only (15.8% vs. 3.8%; p<0.05). In fact, in our cohort of participants with bacteriologically confirmed TB, those with the serological marker of HCV exposure were significantly more likely to be anti-HIV positive, suggesting that HIV seropositivity may identify patients with unknown HCV infection.

Among bacteriologically confirmed TB prisoners (n = 11) chronically infected with HCV (HCV RNA positive), three were also coinfected with HIV. This clinical status may increase the risk of hepatotoxicity induced by the anti-TB drug during treatment [35]. The monitoring of treatment during the first 2 months should identify the Drug-induced liver injury, possibly shortening anti-TB treatment discontinuation and reducing mortality [36]. In addition, factors such as high mobility in and out of the prison environment, adverse effects of the anti-TB drug and use of illicit drug inside prisons may lead to TB treatment dropout.

Participants with evidence of HCV, HBV and syphilis exposure were significantly more likely to be aged > 35 years. Age is considered to be a cumulative risk factor for syphilis, HCV and HBV infections through blood, blood products, and sexual routes [28, 24, 37, 38].

Being transferred from establishments exposes the individual to a greater number of potentially infected persons, especially promoting high-risk sexual partnerships with several individuals, sharing of injecting equipment (needles and syringes) and reuse sharp and unsterile objects for tattooing and body piercing [39]. Once some of these behaviors were observed among participants with evidence of HCV, HBV and HIV exposure harm reduction efforts like condom use or needle exchange needs to be made available to the incarcerated population [40]. It is important to note that HCV RNA was detected in 84.61% of anti-HCV positive samples. Different studies have been reported HCV replication in anti-HCV positive participants (the presence of HCV RNA in serum) with a rate ranging from 45% to 90% [13, 17, 15, 16, 27, 41, 42]. This finding reinforces the importance of access to effective prevention and treatment strategies to reduce the transmission of this infection inside prisons.

Analysis of the data showed that genotype 1 is the predominant genotype circulating in prisoners with TB/HCV co-infection. This finding seems to be similar to the genotype pattern reported in the general population [30] and in the prisoners from the same region [27].

Co-infections have major clinical implications, since one infection may interfere with successful treatment of another or even potentiate a secondary effect of the medication. Therefore, according to Brazilian clinical protocols in TB co-infections with HCV, HIV and/or syphilis, the priority is always to treat HIV first to improve the patient’s immune response and the proportion of favorable therapeutic outcomes. Treatment of viral hepatitis is performed after treatment of TB and undetectable HIV viral load [19, 20, 21].

Jails are an ideal setting for HCV, HBV, syphilis and HIV infections screening and treatment not only because of the high frequency rates of specific risk behaviors which prisoners are exposed but also the potential risk of transmission inside prisons [28]. Therefore, it would be important to establish the routine of serological diagnosis of HCV infection, as well as other STI at the time of the arrival of new inmates and the continuous performance of tests during sentence completion [43]. It is important to note that the majority of inmates that were diagnosed with HCV infection in this study (53.8%) were unaware of their virological condition and also did not receive anti-HCV treatment, highlighting the need of implement strategies to improve the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to HCV in prisoners.

Although prison is an ideal setting for screening and treatment these infections, participants infected with HCV did not initiate treatment. The new guideline that including most HCV-infected patients for treatment with the new DAAs was published in 2019, prior to that, only more severe cases of liver damage, relapses, and HIV coinfection were treated. In addition, time and escort prisoners to obtain the results of genotyping, elastomeric and/or hepatic biopsy to classify the HCV-infected patient in inclusion criteria in the last guideline was a decisive factor in the treatment attempt [44]. The use of HCV DAAs therapy for chronic HCV infection that commonly requires no more than 12 weeks of therapy and causes few adverse effects is now logistically feasible within the prison setting and would aid the HCV elimination effort.

From 2014 to 2017, Brazil experienced a global problem that was the shortage benzathine penicillin, the first-choice drug for the treatment of active syphilis. Benzathine penicillin supply was insufficient in 17 of Brazil’s 27 states, including MS. Therefore, participants with active syphilis were treated with ceftriaxone, an alternative antibiotic drug for the treatment of syphilis that is longer, more expensive and less effective than benzathine penicillin [45, 46].

This study is subject to some limitations. Some potential risk factors associated with HCV, HBV, HIV and syphilis infections may have been under-reported due to the fear of punishment, which may have generated bias in data collection. Moreover, all participants were males, which limit the generalizability of the results to the female inmate population. Finally, we had insufficient numbers of events to examine risk factors for HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections separately [47].

The present study confirmed that prisons represent a crucial setting for sexually transmitted infections, hepatitis C and tuberculosis control. Hence, it is necessary an integrated plan for reducing the spread of these infections in prisons by performing screening, intervention, and prevention and also improve the access to treatment, once an omission of those practices may represent a missed opportunity to control these infections inside and outside of prisons.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to serological markers of exposure to HCV, HBV, HIV and syphilis infections among 279 participants are shown in Table 1 and supporting information. The minimal data set is available from 10.6084/m9.figshare.8204525.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Fundação de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Ensino, Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul – FUNDECT-MS (n. 23/200, TO 0067/12 and 0056/13).

References

- 1.DEPEN. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias INFOPEN–Dezembro de 2015. Ministério da Justiça. p. 7–10, 2015. < https://www.justica.gov.br/news/ha-726-712-pessoas-presas-no-brasil/relatorio_2015_dezembro.pdf >.

- 2.ICPS. International Centre for Prison Studies. World Prision Brief. Kings College London, 2019. < http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All >.

- 3.Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-Mbah M, Gavani A, Kinner SA, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. The Lancet. 2016; 388(10049): 1089–1102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Global+burden+of+HIV%2C+viral+hepatitis%2C+and+tuberculosis+in+prisoners+and+detainees [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report, 2017b. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259366/1/9789241565516-eng.pdf?ua=1. Acessed in: april 15, 2017.

- 5.Bourdillon PM, Gonçalves CC, Pelissari DM, Arakaki-Sanchez D, Ko AI, Croda J, et al. Increase in Tuberculosis Cases among Prisoners, Brazil, 2009–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017; 23(3):496–499. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28221118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacchi FPC, Praça RM, Tatara MB, Simonsen V, Ferrazoli L, Croda MG, et al. Prisons as Reservoir for Community Transmission of Tuberculosis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21(3): 452–455. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Prisons+as+Reservoir+for+Community+Transmission+of+Tuberculosis%2C+Brazil [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginn S. Prison environment and health. BMJ. 2012; 345:e5921 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22988305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barros LAS, Pessoni GC, Teles SA, Souza SM, Matos MA, Martins RM, et al. Epidemiology of the viral hepatitis B and C in female prisoners of Metropolitan Regional Prison Complex in the State of Goiás, Central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013; 46(1): 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamarulzaman A, Reid SE, Schwitters A, Wiessing L, El-Bassel N, Dolan K, et al. Prevention of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in prisoners. Lancet. 2016; 388(10049): 1115–1126. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27427456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorent N.; Sebatunzi O.; Mukeshimana G.; Ende J.; Clerinx J. Incidence and risk factors of serious adverse events during antituberculous treatment in rwanda: a prospective cohort study. Plos One. 2011; 6(5): 19566 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Incidence+and+risk+factors+of+serious+adverse+events+during+antituberculous+treatment+in+rwanda%3A+a+prospective+cohort+study [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu PH, Lin YT, Hsieh KP, Chuang HY, Sheu CC. Hepatitis C Virus Infection Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Active Tuberculosis Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94(33): e1328 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Hepatitis+C+Virus+Infection+Is+Associated+With+an+Increased+Risk+of+Active+Tuberculosis+Disease%3A+A+Nationwide+Population-Based+Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungo JR, Jones D, Ashkin D, Hollender ES, Bernstein D, Albanese AP, et al. Antituberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity. The role of hepatitis C virus and the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998; 157:1871–1876. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Antituberculosis+drug-induced+hepatotoxicity.+The+role+of+hepatitis+C+virus+and+the+human+immunodeficiency+virus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lomtadze N, Kupreishvili L, Salakaia A, Vashakidze S, Sharvadze L, Kempker RR, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Co-Infection Increases the Risk of Anti-Tuberculosis Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity among Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Plos One. 2013; 8(12): e83892 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24367617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim WS, Lee SS, Lee CM, Kim HJ, Ha CY, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatitis C and not Hepatitis B vírus is a risk fator for anti-tuberculosis drug induced liver injury. BMC Infect Dis. 2016; 16(50). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4736472/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards DC, Mikiashvili T, Parris JJ, Kourbatova EV, Wilson JC, Shubladze N, et al. High Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus but Not HIV Co-Infection among Patients with Tuberculosis in Georgia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006; 10(4): 396–401. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16602403 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agha MA, El-Mahalawy II, Seleem HM, Helwa MA. Prevalence of hepatites C vírus in patients with tuberculosis and its impact in the incidence of anti-tuberculosis drug induced hepatotoxicity. The Egyptian Society of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, 2015; 64(1):91–96. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0422763814200380 [Google Scholar]

- 17.BRASIL. Ministério da Justiça. Censo das unidades prisionais e dados agregados. 24 de janeiro de 2016. http://www.justica.gov.br/seus-direitos/politica-penal/transparencia-institucional/estatisticas-prisional/base-de-dados-infopen-csv.csv. Acessed in: april 15, 2017.

- 18.Correa ME, Croda J, Coimbra Motta de Castro AR, Maria do Valle Leone de Oliveira S, Pompilio MA, Omizolo de Souza R, et al. High Prevalence of Treponema pallidum infection in Brazilian Prisoners. Am J Trop Med Hyg, v. 97, n.4, p.1078–1084, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Manual de recomendações para o controle da tuberculose no Brasil. 2019. http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2019/marco/28/manual-recomendacoes.pdf. Acessed in: may, 2019.

- 20.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para o manejo da infecção pelo HIV em dultos. 2018. file:///C:/Users/marco/Downloads/pcdt_adulto_12_2018_web.pdf. Acessed in: may, 2019.

- 21.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Hepatite B e coinfecções. 2017. file:///C:/Users/marco/Downloads/pcdt_hepatite_b_270917%20(1).pdf. Acessed in: may, 2019.

- 22.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Hepatite C e Coinfecções. March de 2017. http://conitec.gov.br/images/Consultas/2017/Relatorio_PCDT_HepatiteCeCoinfeccoes_CP11_2017.pdf. Acessed in: May, 2019.

- 23.Carbone ADAS Paião DS, Sgarbi RV Lemos EF, Cazanti RF Ota MM, et al. Active and latent tuberculosis in Brazilian correctional facilities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15(24). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Active+and+latent+tuberculosis+in+Brazilian+correctional+facilities%3A+a+cross-sectional+study [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costi C, Grandi T, Halon ML, Silva MS, Silva CM, Gregianini TS, et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus in a Group of Patients Newly Diagnosed with Active Tuberculosis in Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017; 112(4): 255–259. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28327789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuniholm MH, Mark J, Aladashvili M, Shubladze N, Khechinashvili G, Tsertsvadze T, et al. Risk Factors and Algorithms to Identify Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B, and HIV among Georgian Tuberculosis Patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2008; 12(1): 51–56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Risk+Factors+and+Algorithms+to+Identify+Hepatitis+C%2C+Hepatitis+B%2C+and+HIV+among+Georgian+Tuberculosis+Patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sirinak C, Kittikraisak W, Pinjeesekikul D, Charusuntonsi P, Luanloed P, Srisuwanvilai LO, et al. Viral Hepatitis and HIV-Associated Tuberculosis: Risk Factors and TB Treatment Outcomes in Thailand. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8: 245 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18638392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pompilio MA, Pontes ERJC, Castro ARCM, Andrade SMO, Stief ACF, Martins RMB, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C among prisoners of Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2011; 17(2): 216–222. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1678-91992011000200013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puga MAM, Bandeira MB, Pompílio MA, Croda J, Rezende GRR, Dorisbor LFP, et al. Prevalence and Incidence of HCV Infection among Prisoners in Central Brazil. PloS One. 2017; 12(1): e0169195 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5218405/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kretzer IF, Livramento A, Cunha J, Gonçalves S, Tosin I, Spada C, et al. Hepatitis C Worldwide and in Brazil: Silent Epidemic—Data on Disease including Incidence, Transmission, Prevention, and Treatment. The Scientific World Journal. 2014; 2014: 1–10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25013871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres MS. Prevalence of infection with hepatitis C virus in blood donors in Campo Grande-MS. Unpublished data, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babudieri S, Soddu A, Murino M, Molicotti P, Muredda AA, Madeddu G, et al. Tuberculosis Screening before Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Therapy in Prisons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012; 18(4): 689–691. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Tuberculosis+Screening+before+Anti-Hepatitis+C+Virus+Therapy+in+Prisons [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vescio MF, Longo B, Babudieri S, Starnini G, Carbonara S, Rezza G, et al. Correlates of Hepatitis C Virus Seropositivity in Prison Inmates: A Meta-Analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health; 2008; 62(4): 305–313. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Correlates+of+Hepatitis+C+Virus+Seropositivity+in+Prison+Inmates%3A+A+Meta-Analysis [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Araújo-Mariz C, Lopes EP, Ximenes RA, Lacerda HR, Miranda-Filho DB, Montarroyos UR, et al. Serological markers of hepatitis B and C in patients with HIV/AIDS and active tuberculosis. J Med Virol. 2016; 88(6): 996–1002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Serological+markers+of+hepatitis+B+and+C+in+patients+with+HIV%2FAIDS+and+active+tuberculosis [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006; 44(1): 6–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16352363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang T, Huang Y, Chang C, Perng C, Huang Y, Hou M. The susceptibility of anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury and chronic hepatitis C infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018; 81(2):111–118. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=The+susceptibility+of+anti-tuberculosis+drug-induced+liver+injury+and+chronic+hepatitis+C+infection%3A+A+systematic+review+and+meta-analysis [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbara A, Chitty S, Roe JK, Ghani R, Collin SM, Ritchie A, et al. Drug-induced liver injury from antituberculous treatment: a retrospective study from a large TB centre in the UK. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2017; 17(231): 1–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Drug-induced+liver+injury+from+antituberculous+treatment%3A+a+retrospective+study+from+a+large+TB+centre+in+the+UK [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gheorghe L, Csiki IE, Iacob S, Gheorghe C. The prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B virus infection in an adult population in Romania: a nationwide survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25:56–64. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328358b0bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutagoma M, Remera E, Sebuhoro D, Kanters S, Riedel DJ, Nsanzimana S. The Prevalence of Syphilis Infection and Its Associated Factors in the General Population of Rwanda: A National Household-Based Survey, 2016. J Sex Transm Dis 2016;2016:4980417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes RM, Cary M, Duarte G, Jesus G, Alarcão J, Torre C, et al. Effectiveness of needle and syringe Programmes in people who inject drugs–An overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(1):309 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Effectiveness+of+needle+and+syringe+Programmes+in+people+who+inject+drugs+%E2%80%93+An+overview+of+systematic+reviews [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heijnen M, Mumtaz GR, Abu-Raddad LJ. Status of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among prisoners in the Middle East and North Africa: review and synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016. May 27;19(1):20873 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larney S, Kopinski H, Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Jarlais DD, Hagan H, et al. Incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and other closed settings: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2013; 58(4): 1215–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23504650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reis NR, Lopes CL, Teles AS, Matos MA, Carneiro MA, Marinho TA, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Patients with Tuberculosis in Central Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011; 15(10): 1397–1402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22283901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almasio PL, Babudieri S, Barbarini G, Brunetto M, Conte D, Dentico P, et al. Recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C in special population groups (migrants, intravenous drug users and prison inmates). Dig Liver Dis. 2011; 43(8): 589–595. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Recommendations+for+the+prevention%2C+diagnosis%2C+and+treatment+of+chronic+hepatitis+B+and+C+in+special+population+groups+(migrants%2C+intravenous+drug+users+and+prison+inmates) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Hepatite C e coinfecções. 2019. http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2017/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-hepatite-c-e-coinfeccoes. Acessed in: May, 2019.

- 45.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Nota informativa conjunta n° 109/2015: Orienta a respeito da priorização da penicilina G benzatina para sífilis em gestantes e penicilina cristalina para sífilis congênita no país e alternativas para o tratamento da sífilis. Brasília, 2015a. http://www.soperj.org.br/novo/imageBank/MS-BR-Nota-109-USO-DE-PENICILINA-EM-GESTANTES-E-CRIANCAS.pdf. Acessed in: May, 2019.

- 46.WHO. World Health Organization. Crescente resistência de antibióticos obriga alterações no tratamento recomendado para infecções sexualmente transmissíveis. http://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5209:crescente-resistencia-aos-antibioticos-obriga-alteracoes-no-tratamento-recomendado-parainfeccoes-sexualmente-transmissiveis&Itemid=816. Acessed in: May, 2019.

- 47.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, Chalmers JD, Marshall R, Maslove DM, et al. Controlo of Confounding and Reporting of Results in Causal Inference Studies. Guidance for Authors from Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019. January;16(1):22–28. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-564PS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to serological markers of exposure to HCV, HBV, HIV and syphilis infections among 279 participants are shown in Table 1 and supporting information. The minimal data set is available from 10.6084/m9.figshare.8204525.