Abstract

Mechanosensitive gastric vagal afferents (GVAs) are involved in the regulation of food intake. GVAs exhibit diurnal rhythmicity in their response to food-related stimuli, allowing time of day-specific satiety signaling. This diurnal rhythmicity is ablated in high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced obesity. Time-restricted feeding (TRF) has a strong influence on peripheral clocks. This study aimed to determine whether diurnal patterns in GVA mechanosensitivity are entrained by TRF. Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (N = 256) were fed a standard laboratory diet (SLD) or HFD for 12 weeks. After 4 weeks of diet acclimatization, the mice were fed either ad libitum or only during the light phase [Zeitgeber time (ZT) 0–12] or dark phase (ZT12–24) for 8 weeks. A subgroup of mice from all conditions (n = 8/condition) were placed in metabolic cages. After 12 weeks, ex vivo GVA recordings were taken at 3 h intervals starting at ZT0. HFD mice gained more weight than SLD mice. TRF did not affect weight gain in the SLD mice, but decreased weight gain in the HFD mice regardless of the TRF period. In SLD mice, diurnal rhythms in food intake were inversely associated with diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity. These diurnal rhythms were entrained by the timing of food intake. In HFD mice, diurnal rhythms in food intake and diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity were dampened. Loss of diurnal rhythmicity in HFD mice was abrogated by TRF. In conclusion, diurnal rhythmicity in GVA responses to food-related stimuli can be entrained by food intake. TRF prevents the loss of diurnal rhythmicity that occurs in HFD-induced obesity.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Diurnal control of food intake is vital for maintaining metabolic health. Diet-induced obesity is associated with strong diurnal changes in food intake. Vagal afferents are involved in regulation of feeding behavior, particularly meal size, and exhibit diurnal fluctuations in mechanosensitivity. These diurnal fluctuations in vagal afferent mechanosensitivity are lost in diet-induced obesity. This study provides evidence that time-restricted feeding entrains diurnal rhythmicity in vagal afferent mechanosensitivity in lean and high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced obese mice and, more importantly, prevents the loss of rhythmicity in HFD-induced obesity. These data have important implications for the development of strategies to treat obesity.

Keywords: circadian rhythmicity, obesity, stomach, time-restricted feeding, vagal afferents

Introduction

Cyclical endogenous processes, determined by the light/dark cycle and coordinated by peripheral clocks present in tissues and cells throughout the body (Schibler et al., 2003; Lowrey and Takahashi, 2004), enable mammals to anticipate predictable changes in the environment and adapt accordingly. These peripheral clocks are synchronized by a “master” clock located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which receives information about light and dark via a neural pathway from the retina (Gillette and Tischkau, 1999).

Gastric vagal afferents (GVAs) play a role in the regulation of food intake signaling to the brain the amount of food consumed (Cummings and Overduin, 2007). There are two classes of GVA based on their response to mechanical stimulation (Page et al., 2002; Kentish and Page, 2014). Mucosal receptors penetrate into the gastric mucosa and respond to fine tactile stimuli (Page et al., 2002) such as food particles brushing against the mucosal surface of the stomach. They are thought to be involved in the regulation of gastric motor function to delay gastric emptying until the food within the stomach has been sufficiently broken down and digested (Becker and Kelly, 1983). Tension receptors have endings in the muscular regions of the stomach wall and signal the stretch that occurs as a meal is consumed and the stomach fills. Tension receptors are involved in the regulation of motor reflexes that control gastric accommodation. In addition, they signal the degree of fullness of the stomach that leads to feelings of satiety and ultimately the termination of a meal (Wang et al., 2008). We have demonstrated that there is diurnal expression of clock genes within the cell bodies of vagal afferents that display diurnal rhythmicity in response to food-related mechanical stimuli (Kentish et al., 2013). Tension and mucosal receptors display diurnal rhythmicity in their response to mechanical stimuli (Kentish et al., 2013), which regulates food intake to time of day-specific energy demand. In mice, the nadir in GVA mechanosensitivity is associated with greater food intake during the dark period when energy demand is high. The converse is true in the light phase (LP), when the peak in GVA mechanosensitivity is associated with reduced food intake and meal size (Kentish et al., 2013). Therefore, GVA satiety signaling appears to be finely tuned to control food intake in line with energy demand. In high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced obesity, diurnal rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity (Kentish et al., 2016) and the fine control of food intake regulation is lost such that the mice graze continuously on the HFD throughout the day and night (Pendergast et al., 2013; Kentish et al., 2016).

Feeding schedules exert a strong entraining influence on peripheral oscillators, modulating behavior along with visceral and metabolic rhythms overriding signals from the SCN (Escobar et al., 1998; Damiola et al., 2000; Báez-Ruiz et al., 2005; Davidson et al., 2005). It has been demonstrated that providing mice HFD solely during the dark phase (DP), when they are active, resets peripheral clocks and abrogates many of the adverse metabolic consequences of HFD-induced obesity. This includes restoring diurnal rhythms in resting energy expenditure and hepatic glucose metabolism (Hatori et al., 2012) and reducing hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and inflammation (Chaix et al., 2014). It is unknown whether time-restricted feeding (TRF) can entrain rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity and if it can prevent the abrogation of GVA diurnal rhythmicity observed in HFD-induced obese mice. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of TRF on GVA mechanosensitivity in lean and HFD-induced obese mice.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval.

All studies were approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committees of the University of Adelaide and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Adelaide, Australia. The design, conduct, and reporting of all research herein are in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010).

Mice.

Male C57BL/6 mice (N = 256), aged 7 weeks, were housed with littermates in groups of 3–5 for 1 week before experimentation. During this period, all mice were housed under a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, with lights on at 0600 [Zietgeber time (ZT) 0] and off at 1800 h (ZT12) and had ad libitum (AL) access to a standard laboratory diet (SLD; 12% energy from fat). During the whole experiment, mice had AL access to water. At 8 weeks of age, the mice were allocated into two groups with AL access to either an SLD (n = 128) or an HFD (60% energy from saturated fat, N = 128) for 4 weeks to acclimatize to the diet. After 4 weeks, the mice were further subdivided into three groups per diet. One group/diet had AL access to food: SLD-AL (n = 48) and HFD-AL (n = 48) mice. The second group/diet only had access to food during the LP from ZT0 to ZT12: SLD-LP (n = 40) and HFD-LP (n = 40) mice. A third group/diet only had access to food during the DP: SLD-DP (n = 40) and HFD-DP (n = 40) from ZT12 to ZT24 (DP-mice). These feeding regimes (see Fig. 1) continued for a further 8 weeks until the point of the electrophysiology experiments, when the mice were taken every 3 h for electrophysiology experiments commencing at ZT0 (n = 5–6 per time point). The mice were randomly assigned a time for electrophysiology experiments to minimize possible cage effects due to the group housing. An additional group of age-matched mice were fed an SLD (n = 20) or an HFD (n = 20) for 4 weeks. After this period, the mice were taken every 6 h (ZT0, 6, 12, and 18) for electrophysiology experiments to determine whether the observed changes were due to prevention or reversal of HFD effects.

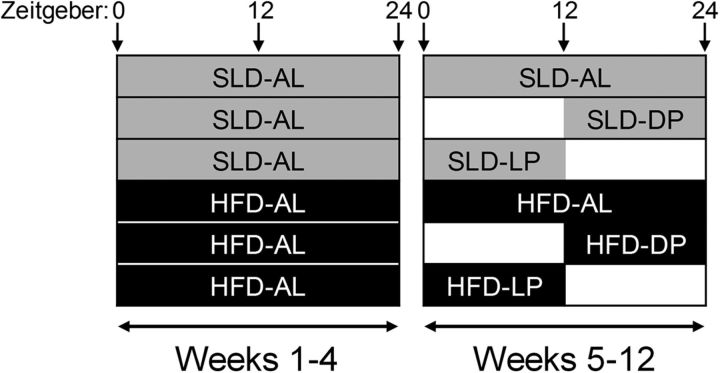

Figure 1.

Schematic of the 12-week feeding regime. The shaded areas indicate food availability. At 8 weeks of age, the mice were allocated into two groups with AL access to either an SLD (gray shaded area indicates food availability) or an HFD (black shaded area indicates food availability). After 4 weeks, the mice were further subdivided into three groups per diet. One group/diet had AL access to food (SLD-AL and HFD-AL). The second group/diet only had access to food during the LP from ZT0 to ZT12 (SLD-LP and HFD-LP). A third group/diet only had access to food during the DP from ZT12 to ZT24 (SLD-DP and HFD-DP). These feeding regimes continued for a further 8 weeks.

Metabolic monitoring.

A subgroup of mice randomly allocated from each of the groups above (n = 8/diet) were individually housed in metabolic monitoring cages (Promethion; Sable Systems International) for 12 weeks to determine food intake under the different dietary conditions and feeding regimes. There was no difference in the initial weight or weight gain between the individually housed metabolic monitoring subgroups and the group-housed mice.

Mouse in vitro GVA electrophysiology preparation.

This preparation has been described in detail previously (Page et al., 2002). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed via exsanguination followed by decapitation. A midline incision was made in the thorax and the stomach and esophagus with attached vagal nerves removed. The stomach and esophagus were opened longitudinally and pinned mucosal side up in an organ bath with Krebs solution containing the following (in mm): 118.1 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 25.1 NaHCO3, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4.7H2O, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.0 citric acid, 11.1 glucose, and 0.001 nifedipine, bubbled with 95% O2- 5% CO2.

Identification of subtypes of GVA.

The characteristics of subtypes of GVA and their response to mechanical stimuli has been described in detail previously (Page et al., 2002). Briefly, tension receptors respond to both mucosal stroking and circular tension and mucosal receptors respond to mucosal stroking, but not circular tension. Receptive fields for the GVA endings were initially located in the stomach using a brush. Once located, more refined stimuli were applied. For mucosal receptors, mucosal stroking was performed using a 50 mg calibrated von Frey hair, which was stroked across the receptive field at a rate of ∼5 mms−1. For tension receptors, tension was applied using a threaded hook attached to an underpinned point adjacent to the receptive field. The threaded hook was attached to a cantilever system via a pulley close to the preparation. A 3 g standard weight was then placed on the opposite end of the cantilever for 1 min. Single units were discriminated by action potential shape, duration, and amplitude using Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design).

Data analysis.

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM with n = the number of animals. Weight gain data were analyzed using a mixed-model ANOVA (fixed factors: diet regime and weekly weight measurements; random factors: mouse allocation and variation in weight gain over time within groups). Final body weight and gonadal fat pad mass were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Food intake data from the end of the 12th week were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. GVA mechanosensitivity over a 24 h period was compared between diet groups at the same time point using a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Significance between ZT6 and ZT18 within the same diet group was determined using an unpaired t test. Significance between diet groups at ZT6 and ZT18 was determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Results

Diet-induced obese mice

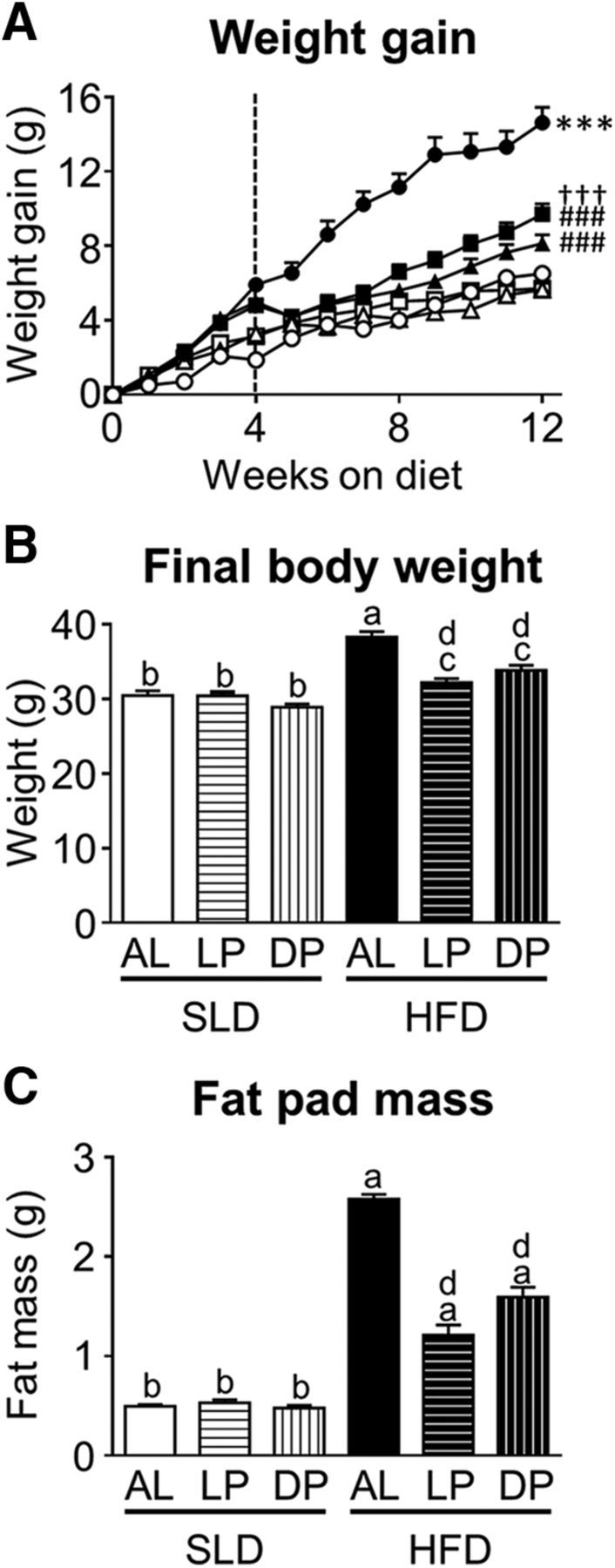

Mouse weight gain, final weight, and fat pad mass are illustrated in Figure 2. At 4 weeks, mice fed an HFD (28.24 ± 0.50 g; n = 24) were significantly heavier than mice fed an SLD (26.01 ± 0.32 g; n = 24: p < 0.001, unpaired t test, T(46) = 3.782; Fig. 2A); however, within each dietary group, the weights of the mice in the three subgroups were similar. Over the following 8 weeks (weeks 5–12), HFD-AL mice gained significantly more weight than the HFD-LP mice (p < 0.001 diet (F(1,86) = 97.3) and time (F(7,86) = 283.8) effects with a significant interaction (p < 0.001; F(7,86) = 26.3; Fig. 2A) and HFD-DP mice (p < 0.001 diet F(1,86) = 37.7 and time F(7,86) = 417.8) effects, but no interaction. The HFD-DP mice gained significantly more weight than the HFD-LP mice (p < 0.001 diet F(1,78) = 148.59 and time F(7,78) = 249.59) effects, but no interaction (Fig. 2A). There was no difference in weight gain between mice in the SLD groups. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect of diet (p < 0.0001; F(1,250) = 303.2) and feeding regime (p < 0.0001; F(2,250) = 87.81) and an interaction (p < 0.0001; F(2,250) = 75.23; Fig. 2B) between diet and feeding regime on final body weight. HFD-AL mice were significantly heavier than all other groups of mice (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the final body weight of HFD-DP and HFD-LP mice, which were both significantly heavier than the mice in the SLD groups (p < 0.05; Fig. 2B). There was no statistical difference in the final body weight of the mice in the SLD groups. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect of diet (p < 0.0001; F(2,250) = 649.9) and feeding regime (p < 0.0001; F(2,250) = 65.81) and an interaction (p < 0.0001; F(2,250) = 70.38; Fig. 2C) between diet and feeding regime on gonadal fat pad mass. Gonadal fat pad mass was significantly higher in the HFD mice compared with the SLD mice (p < 0.001). Gonadal fat pad mass in HFD-AL mice was significantly higher than HFD-DP and HFD-LP mice (p < 0.001) and higher in HFD-DP compared with HFD-LP mice (p < 0.001). There was no difference in gonadal fat pad mass (Fig. 2C) between mice in the SLD groups.

Figure 2.

Mouse body weight and gonadal fat pad mass. A, Weight gain (grams) in mice fed an SLD (open symbols) or HFD (closed symbols) for 4 weeks, for diet acclimatization and then split into three groups/diet (at dotted line) and fed either AL (circles; n = 48/diet group), just during the LP (ZT0–12; triangles; n = 40/diet group), or just during the DP (ZT12-ZT0; squares; n = 40/diet group). ***p < 0.001 versus all other groups, mixed-model ANOVA at weeks 5–12. ###p < 0.001 versus HFD-AL mice, †††p < 0.001 versus HFD-LF. B, C, Final body weight (grams) (B) and gonadal fat pad mass (grams) (C) in SLD and HFD mice fed AL (n = 48/diet group), just during the LP (n = 48/diet group), or just during the DP (n = 48/diet group). ap < 0.05 versus all other groups; bp < 0.05 versus all HFD groups; cp < 0.05 versus all SLD groups; and dp < 0.05 versus HDF-AL group, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test.

Food intake

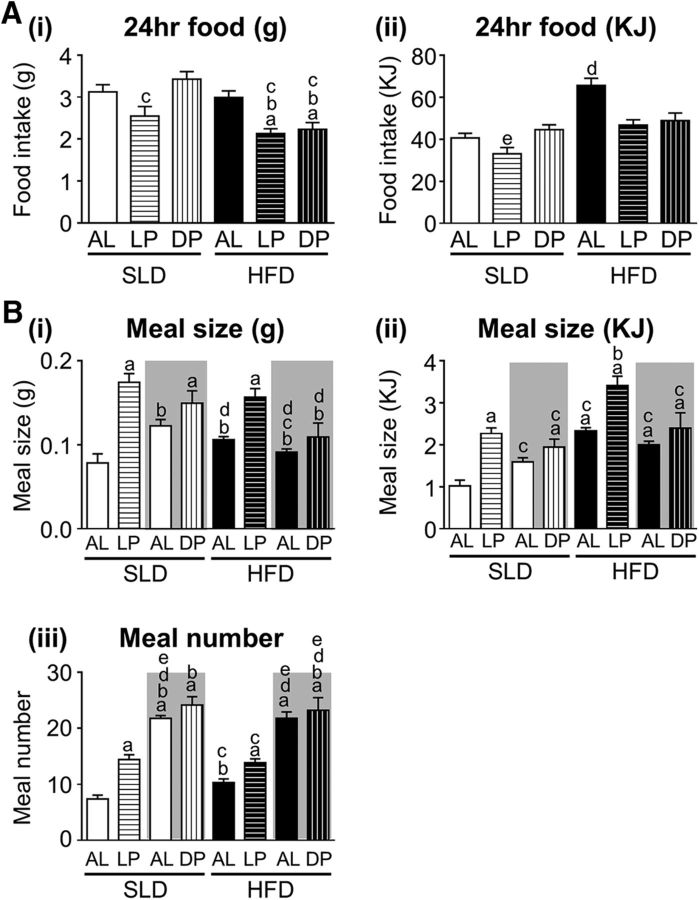

The effect of diet and feeding regime on food intake is illustrated in Figure 3. There was a significant effect of diet (p < 0.001; F(1,42) = 17.3) and feeding regime (p < 0.001; F(2,42) = 9.13) on 24 h food intake (grams) and a significant interaction between diet and feeding regime (p < 0.01; F(2,42) = 5.2; Fig. 3A). The HFD-LP and HFD-DP mice were unable to compensate for the TRF regime and food intake was significantly reduced compared with HFD-AL, SLD-AL, and SLD-DP mice (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 respectively). SLD-LP mice consumed significantly less food than the SLD-DP mice (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Food intake in mice fed an SLD or HFD AL (n = 8/diet group) just during the LP (n = 8/diet group) or just during the DP (n = 8/diet group). A, The 24 h food intake in grams consumed (Ai) and energy intake in kilojoules (Aii). ap < 0.01 versus SLD-AL; bp < 0.01 versus HFD-AL; cp < 0.01 versus SLD-DP; dp < 0.01 versus all other groups; and dp < 0.01 versus all HFD groups, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test. B, Meal size in grams consumed (Bi), energy intake in kilojoules (Bii), and meal number (Biii). The gray shaded and unshaded regions represent the dark and LP measurements, respectively. ap < 0.05 versus LP-SLD-AL; bp < 0.05 versus LP-SLD-LP; cp < 0.05 versus DP-SLD-DP; dp < 0.05 versus LP-HFD-LP, and ep < 0.05 versus LP-HFD-AL, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test.

The effect of diet and feeding regime on energy intake is illustrated in Figure 3Aii. There was a significant effect of diet (p < 0.0001; F(1,42) = 37.21) and feeding regime (p < 0.001; F(2,42) = 10.44) on 24 h energy intake (kilojoules) and a significant interaction between diet and feeding regime (p < 0.01; F(2,42) = 6.47; Fig. 3Aii). The TRF SLD-LP and SLD-DP mice were able to compensate for the 12 h of food restriction and energy intake was not significantly different from SLD-AL mice (Fig. 3Aii). In contrast, HFD-LP and HFD-DP mice were unable to fully compensate for the 12 h TRF period and energy intake was significantly reduced compared with HFD-AL mice (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively, vs HFD-AL; Fig. 3Aii). In the HFD-DP and HFD-LP mice, energy intake was not significantly different from that of SLD-AL mice (Fig. 3Aii).

In SLD-AL mice, meal size (in grams an kilojoules) and meal frequency was significantly higher during the DP, when mice are active, compared with the LP (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B). As reported previously (Kentish et al., 2016), this diurnal variation in meal size, but not meal frequency, was lost in HFD-AL mice (p < 0.05, F(1,14) = 5.157, time of day effect; p > 0.05, F(1,14) = 0.05, diet effect; and p < 0.001, F(1,14) = 20.84, interaction between diet and time of day; Fig. 3B). The frequency (p < 0.01; F(7,56) = 30.2) and meal size (grams: p < 0.001, F(7,56) = 10.09; kilojoules: p < 0.001, F(7,56) = 13.51) was significantly enhanced in the SLD-LP mice compared with the LP meal size and frequency in SLD-AL mice (Fig. 3B). In contrast, there was no difference in meal frequency and meal size between SLD-DP mice and DP food intake in SLD-AL mice (Fig. 3B). Meal size (grams: p < 0.05, F(7,56) = 10.09; kilojoules: p < 0.01, F(7,56) = 13.51), but not frequency, was increased in HFD-LP mice compared with LP feeding in HFD-AL mice (Fig. 3B). There was no significant difference in meal size and meal frequency between HFD-DP mice and DP feeding in HFD-AL mice (Fig. 3B).

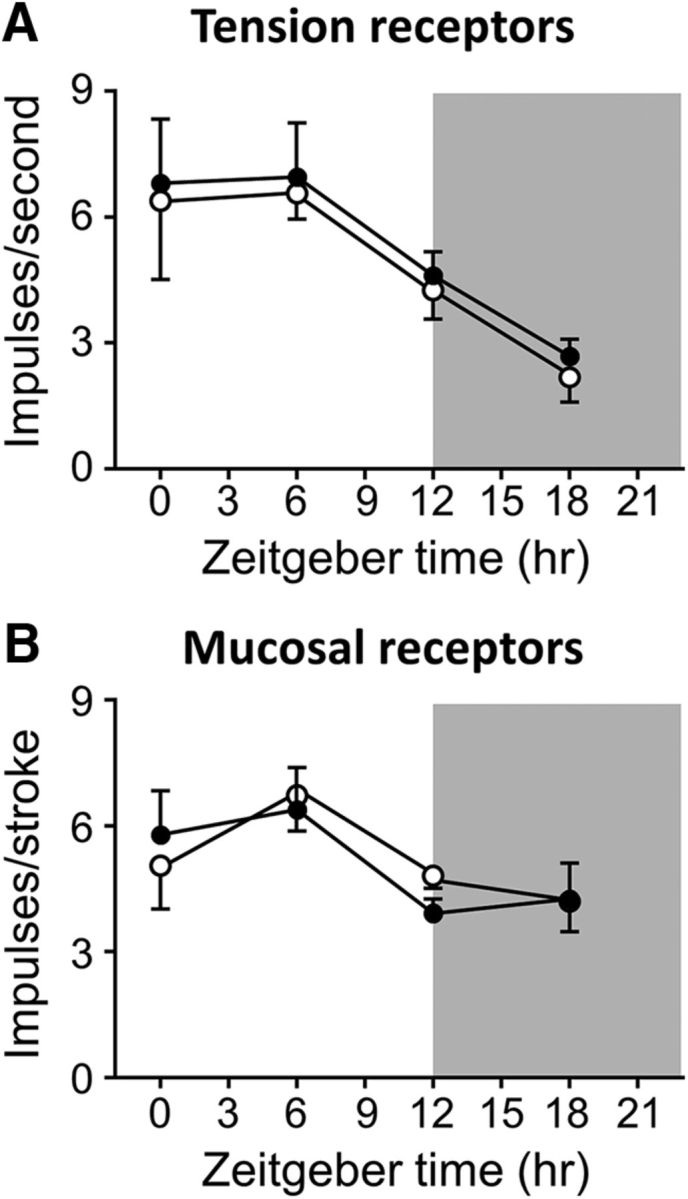

Diurnal oscillations in GVA mechanosensitivity

The diurnal rhythmicity of GVA responses to mechanical stimulation after 4 weeks on an SLD or HFD and before commencement of the TRF regimes is illustrated in Figure 4. In mice fed an SLD or HFD for 4 weeks, there was significant variation in tension receptor mechanosensitivity (p = 0.0006; F(3,36) = 7.227; time-of-day effect; Fig. 4A). Two-way ANOVA revealed that diet had no impact on tension receptor mechanosensitivity (p = 0.5881) and there was no interaction between diet and time of day (p = 0.9999). Similarly, in mice fed an SLD or HFD for 4 weeks, there was a significant variation in mucosal receptor mechanosensitivity (p = 0.0292 (F(3,35) = 3.371; time-of-day effect; Fig. 4B). Again, the two-way ANOVA revealed that diet had no impact on mucosal receptor mechanosensitivity (p = 0.8562) and there was no interaction between diet and time of day (p = 0.7840).

Figure 4.

Diurnal variation in GVA mechanosensitivity is still present after 4 weeks of HFD feeding. A, Response of gastric tension receptors to a 3 g stretch in mice fed AL either an SLD (n = 20; n ≥ 5/time point; ○) or an HFD (n = 20; n ≥ 5/time point; ●) for 4 weeks. There is no significant difference in the diurnal variation of gastric tension receptor responses to a 3 g stretch between SLD- and HFD-fed mice. B, Response of gastric mucosal receptors to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair in mice fed AL either an SLD (○) or HFD (●) for 4 weeks. p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA.

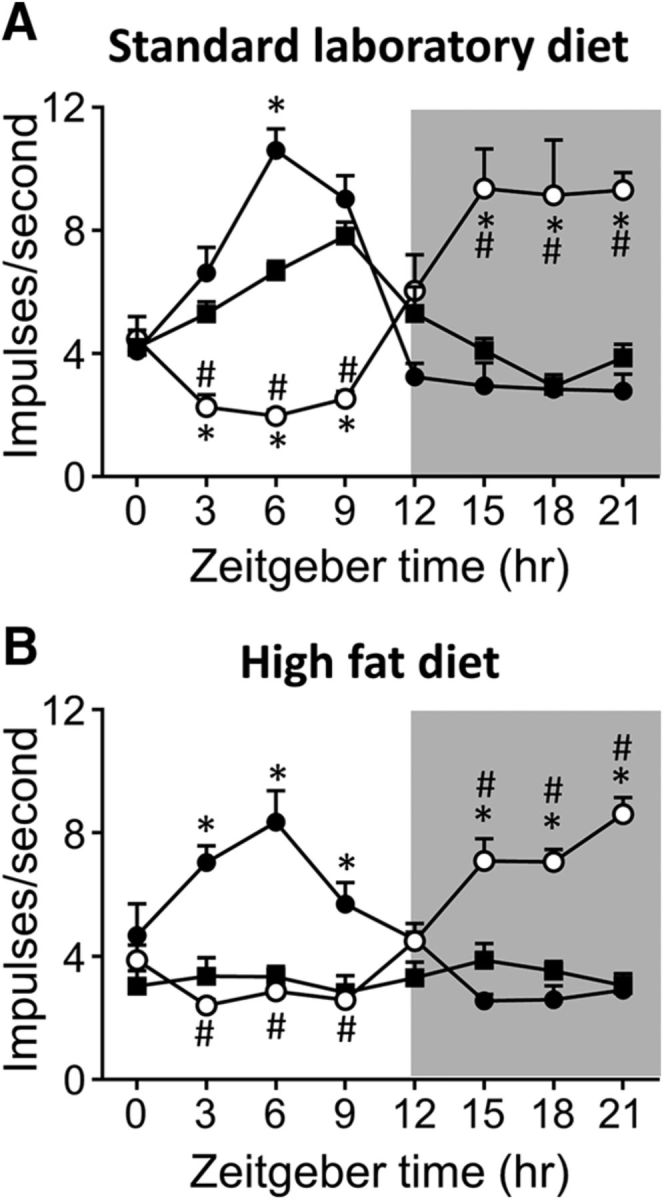

The diurnal rhythmicity of GVA tension receptor responses to 3 g stretch at the 12-week time point is illustrated in Figure 5 and Table 1. In SLD-AL mice, GVA tension receptors exhibited a diurnal rhythmicity in response to a 3 g stretch (p < 0.0001; F(7,40) = 2.280; Fig. 5A, Table 1), with a peak response at ZT9 and a nadir at ZT18 (Fig. 5A). A similar diurnal mechanosensitivity profile was observed in the SLD-DP mice (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 0.585; Fig. 5A, Table 1), although the acrophase was earlier at ZT6 (Fig. 5A). In SLD-LP mice, the diurnal rhythmicity in mechanosensitivity (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.524; Fig. 5A) was reversed (Table 1), with an acrophase at ZT15 and a nadir at ZT6. In HFD-AL mice, the response of gastric tension receptors to a 3 g stretch was consistent across a 24 h period and exhibited no diurnal rhythmicity (Fig. 5B, Table 1). However, in HFD-LP (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.545) and HFD-DP (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.018) mice, diurnal rhythmicity was maintained. In HFD-DP mice, the acrophase was at ZT6 and the nadir at ZT15 and, in the HFD-LP mice, this was reversed with an acrophase during the dark period at ZT21 and a nadir during the light period at ZT3 (Fig. 5B, Table 1).

Figure 5.

Diurnal variation in GVA tension receptor mechanosensitivity in mice fed either an SLD (A; n = 128; n ≥ 5/time points/diet regime) or an HFD (B; n = 128; n ≥ 5/time points/diet regime) for 12 weeks. A, Diurnal variation in tension receptor responses to a 3 g stretch observed in mice fed an SLD AL (■) was maintained when feeding was restricted to the DP (ZT12–24; ●), but reversed when feeding was limited to the LP (ZT0–12; ○). B, Diurnal variation in gastric tension receptor responses to a 3 g stretch observed in SLD-mice was lost in mice fed an HFD AL (■). Diurnal variation in gastric tension receptor mechanosensitivity was maintained in HFD mice when food availability was restricted to the DP (ZT12–24; ●). In addition, although reversed, diurnal variation in tension receptor mechanosensitivity was also maintained in HFD mice when food availability was restricted to the LP (ZT0–12; ○). *p < 0.05 versus responses at an equivalent time point in mice fed AL (■), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test. #p < 0.05 versus responses at an equivalent time point in mice fed just during the 12 h dark period (●), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test.

Table 1.

Response (impulses/s) of gastric tension receptors to a 3 g stretch in tissue collected at ZT6 and ZT18

| Diet–feeding | ZT6 | ZT18 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLD-AL (n = 6) | 6.7 ± 0.3b,c,d,e | 2.9 ± 0.4b,e | p < 0.0001 [1.188 (5, 5)] |

| SLD-LP (n = 5) | 2.0 ± 0.4a,c,f | 9.1 ± 1.80a,c,d,f | p = 0.004 [87.83 (4, 4)] |

| SLD-DP (n = 5) | 10.6 ± 0.7a,b,d,e | 2.8 ± 0.12b,e | p < 0.0001 [35.70 (4, 4)] |

| HFD-AL (n = 6) | 3.3 ± 0.3a,c,f | 3.5 ± 0.3b,e | p = 0.7 [1.193 (5, 5)] |

| HFD-LP (n = 5) | 2.7 ± 0.4a,c,f | 7.0 ± 0.4a,c,d,f | p < 0.0001 [1.311 (4, 4)] |

| HFD-DP (n = 5) | 8.4 ± 1.0b,d,e | 2.6 ± 0.5b,e | p = 0.0008 [5.045 (4, 4)] |

| Significance | p < 0.0001 [2.445 (5, 26)] | p < 0.0001 [2.142 (5, 26)] |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance between ZT6 and ZT18 within the same diet group was determined using an unpaired t test [F(DFn, Dfd)]. Significance between diet groups at the same time point was determined using a one-way ANOVA [F(DFn, Dfd)] followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

ap < 0.05 versus SLD-AL.

bp < 0.05 versus SLD-LP.

cp < 0.05 versus SLD-DP.

dp < 0.05 versus HFD-AL.

ep < 0.05 versus HFD-LP.

fp < 0.05 versus HFD-DP.

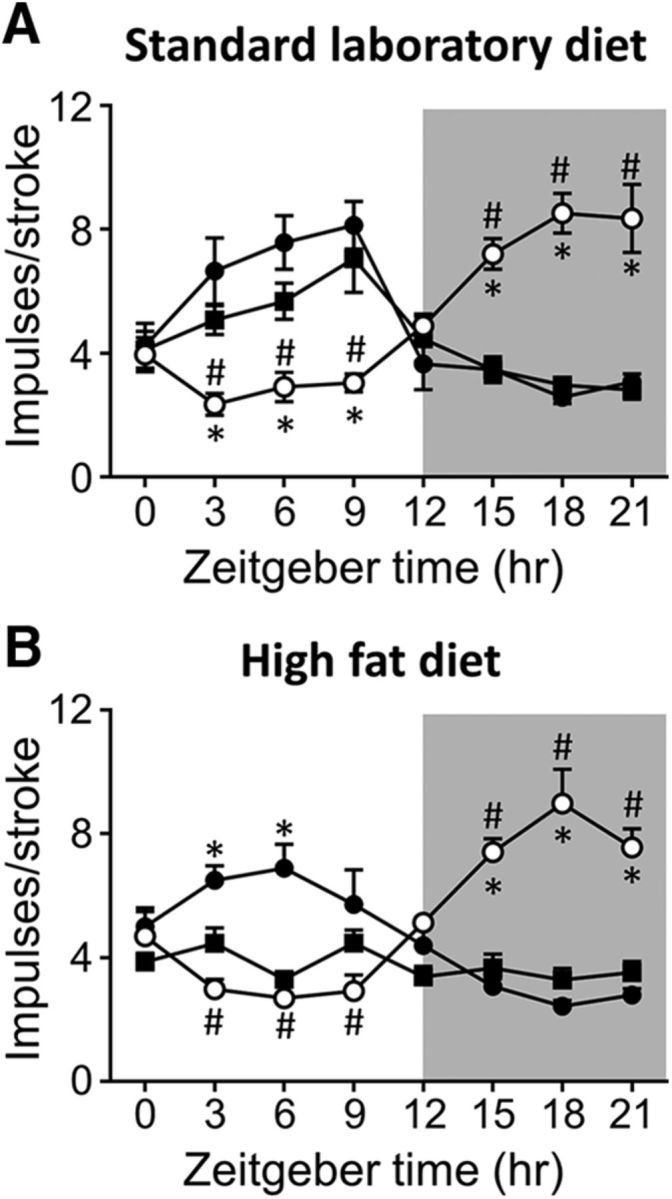

The diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mucosal receptor responses to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg calibrated von Frey hair at the 12-week time point is illustrated in Figure 6 and Table 2. In SLD-AL mice, GVA mucosal receptors exhibited a diurnal rhythmicity in response to stroking (p < 0.0001; F(7,40) = 1.278; Fig. 6A, Table 2), with a peak response at ZT9 and a nadir at ZT21 (Fig. 6A). A similar diurnal mechanosensitivity profile was observed in the SLD-DP mice (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.097; Fig. 6A, Table 2), with an acrophase at ZT9 and a nadir at ZT18 (Fig. 6A). In SLD-LP mice, the diurnal rhythmicity in mechanosensitivity was reversed (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.185; Fig. 6A, Table 2), with an acrophase at ZT18 and a nadir at ZT3. In HFD-AL mice, the response of gastric mucosal receptors to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair was not significantly different across a 24 h period and therefore did not exhibit diurnal rhythmicity (Fig. 6B, Table 2). However, in HFD-LP (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 0.703) and HFD-DP (p < 0.0001; F(7,32) = 1.032) mice, diurnal rhythmicity was maintained (Fig. 6B, Table 2). In HFD-DP mice, the acrophase was at ZT6 and the nadir at ZT18 (Fig. 6B). In the HFD-LP mice, this was reversed, with an acrophase during the dark period at ZT18 and a nadir during the light period at ZT6 (Fig. 6B, Table 2).

Figure 6.

Diurnal variation in GVA mucosal receptor mechanosensitivity in mice fed either an SLD (A; n = 128; n ≥ 5/time points/diet regime) or an HFD (B; n = 128; n ≥ 5/time points/diet regime) for 12 weeks. A, Diurnal variation in mucosal receptor responses to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair observed in mice fed an SLD AL (■) was maintained when feeding was restricted to the DP (ZT12–24; ●), but reversed when feeding was limited to the LP (ZT0–12; ○). B, Diurnal variation in gastric mucosal receptor responses to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair observed in SLD-mice was lost in mice fed an HFD AL (■). Diurnal variation in gastric mucosal receptor mechanosensitivity was maintained in HFD mice when food availability was restricted to the DP (ZT12–24; ●). In addition, although reversed, diurnal variation in mucosal receptor mechanosensitivity was also maintained in HFD mice when food availability was restricted to the LP (ZT0–12; ○). *p < 0.05 versus responses at an equivalent time point in mice fed AL (■), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test. #p < 0.05 versus responses at an equivalent time point in mice fed just during the 12 h dark period (●), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc test.

Table 2.

Response (impulses/stroke) of gastric mucosal receptors to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair in tissue collected at ZT6 and ZT18

| Diet–feeding | ZT6 | ZT18 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLD-AL (n = 6) | 5.7 ± 0.6b,c,d,e | 3.0 ± 0.2b,e | p = 0.0015 [7.494 (5, 5)] |

| SLD-LP (n = 5) | 2.9 ± 0.5a,c,f | 8.5 ± 0.6a,c,d,f | p = 0.0001 [1.788 (4, 4)] |

| SLD-DP (n = 5) | 7.6 ± 0.9a,b,d,e | 2.6 ± 0.2b,e | p = 0. 0005 [19.31 (4, 4)] |

| HFD-AL (n = 6) | 3.3 ± 0.2a,c,f | 3.3 ± 0.4b,e | p = 0.97 [2.926 (5, 5)] |

| HFD-LP (n = 5) | 2.7 ± 0.4a,c,f | 9.0 ± 1.1a,c,d,f | p = 0.0007 [6.74 (4, 4)] |

| HFD-DP (n = 5) | 6.9 ± 0.8b,d,e | 2.4 ± 0.2b,e | p = 0.0005 [16.12 (4, 4)] |

| Significance | p < 0.0001 [0.8023 (5, 26)] | p < 0.0001 [1.703 (5, 26)] |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance between ZT6 and ZT18 within the same diet group was determined using an unpaired t test [F(DFn, Dfd)]. Significance between diet groups at the same time point was determined using a one-way ANOVA [F(DFn, Dfd)] followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

ap < 0.05 versus SLD-AL.

bp < 0.05 versus SLD-LP.

cp < 0.05 versus SLD-DP.

dp < 0.05 versus HFD-AL.

ep < 0.05 versus HFD-LP.

fp < 0.05 versus HFD-DP.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that diurnal rhythmicity in GVA responses to food-related stimuli can be entrained by food intake and that the loss of diurnal rhythmicity in HFD conditions can be abrogated by TRF.

GVA mechanosensitivity is inversely associated with food intake

Meal size in rodents varies dramatically between the LP and DP, with increased meal size and meal frequency during the DP reported in both rats and mice (Rosenwasser et al., 1981; Kentish et al., 2016) and observed in the current study. These changes in food intake are inversely related to the diurnal rhythmicity in GVA responses to food-related stimuli (Kentish et al., 2013). Activation of GVAs by distension of the stomach has been shown to induce satiety (Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity provides a possible control mechanism for diurnal food intake. However, vagal afferents are also involved in reflex pathways involved in gastrointestinal motility, including gastric slow waves (Królczyk et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2004) and gastric emptying (Królczyk et al., 2001), both of which exhibit diurnal variation (Trout et al., 1991; Aviv et al., 2008). Therefore, the oscillations in vagal afferent mechanosensitivity may be involved in other vagally mediated processes.

Diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity is lost in HFD-induced obesity

In HFD mice, diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity is lost (Kentish et al., 2016). Consistent with these observations, diurnal rhythms in food intake are dampened (Kentish et al., 2016). The timing of food intake and even the nutrient composition of a meal has a powerful influence on peripheral clocks (Ribas-Latre and Eckel-Mahan, 2016), which are intimately connected to metabolism (Green et al., 2008; Asher and Schibler, 2011; Bass, 2012; Eckel-Mahan and Sassone-Corsi, 2013). Evidence for this is provided in clock gene knock-out mice observed to have a variety of metabolic disorders (Sahar and Sassone-Corsi, 2012). For example, diurnal locomotor output cycles kaput (Clock) mutant mice become hyperphagic and obese when placed in constant darkness (Turek et al., 2005). In addition, they developed hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and hepatic steatosis (Turek et al., 2005). Further, loss of brain and muscle arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein (BMAL1) leads to disruption of oscillations in triglyceride and glucose levels (Rudic et al., 2004), whereas mice lacking Cryptochrome (Cry1 and/or Cry2) show impaired glucose tolerance (Lamia et al., 2011). Therefore, in HFD mice, the lack of diurnal rhythms in food intake could have significant implications for various metabolic processes. Therefore, both the increase in energy intake and the possible disruption in metabolism could account for the increase in weight gain observed in HFD mice.

TRF entrains GVA mechanosensitivity

In lean SLD mice, TRF did not alter weight gain and gonadal fat pad mass over an 8-week period compared with mice fed AL. Presumably, this is because they compensated food intake during the 12 h that food was available. It has been demonstrated previously that mice fed an SLD only during the LP gain more weight over 9 d than mice fed SLD only during the DP (Bray et al., 2013). In the current study, after a 7 or 14 d exposure to the TRF regimen, there was no difference in weight gain between SLD-LP and SLD-DP mice. The reason for this discrepancy is uncertain and requires further investigation. It has been suggested that social isolation is a contributing factor to the development of obesity in mice (Nonogaki et al., 2007). In the study by Bray et al. (2013), mice were individually housed. In the current study, the majority of mice were group housed; however, there was a subgroup of mice individually housed for metabolic monitoring. There were no observed differences in weight gain between this group and the mice that were group housed. Therefore, the observed differences are unlikely to be due to group or single housing.

In SLD mice feed restricted to the DP, the diurnal rhythmicity of GVA tension and mucosal receptors was enhanced but still in phase with the rhythmicity observed in SLD mice fed AL. Normally, AL fed mice eat the majority of their food during the DP (Kentish et al., 2016) and therefore the two groups of mice had a similar eating pattern. The enhanced vagal afferent mechanosensitivity, observed during the LP in SLD-DP compared with SLD-AL mice suggests that the absence of food intake during the LP is important for the rise in mechanosensitivity. The SLD-AL mice still eat a small amount of food during the LP, which could account for the smaller rise in mechanosensitivity compared with the SLD-DP mice, for which no food was available during the LP. This requires further investigation. In SLD-LP mice, the diurnal rhythmicity of GVA responses to mechanical stimulation was reversed compared with the SLD-AL mice. This suggests that the timing of food intake plays an important role in entraining diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity. Further, although there is no direct evidence for physical activity affecting GVA mechanosensitivity, there is evidence that physical activity can entrain diurnal rhythms (Tahara et al., 2017). Therefore, possible changes in physical activity as a consequence of the TRF could affect diurnal rhythms in GVA mechanosensitivity. This requires further investigation.

TRF prevents the loss of diurnal rhythms in GVA mechanosensitivity observed in HFD-induced obesity

HFD mice fed AL gained significantly more weight than the TRF HFD mice regardless of whether the TRF was during the LP or DP. Further, the HFD-LP mice gained significantly less weight and gonadal fat pad mass than the HFD-DP mice. This contradicts published data indicating that mice who consume HFD only during the LP exhibit increased body weight compared with mice that only consume HFD during the DP (Arble et al., 2009). This discrepancy could be due to the inclusion, in the current study, of a diet acclimatization period before exposure to a TRF regime. In the Arble et al. (2009) study, the simultaneous change in diet and restricted food availability could have been a major stress, particularly for the HFD-LP mice, in which food was out of phase with their normal feeding habits. This could have affected the results obtained. Another possible reason for the discrepancy is that there was a difference in the level of fat in the regular diets before the commencement of the study. In the Arble et al. (2009) study, the mice were on a 6% energy from fat diet and, in the current study, the mice were on a 12% energy from fat diet. Therefore, the metabolic state of the mice before the commencement of the study might have been different. This may account for the discrepencies in weight gain between the two studies; however, this requires further investigation.

Diurnal rhythmicity of GVA mechanosensitivity is lost in chronic HFD mice (Kentish et al., 2016). In the current study, diurnal rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity was still observed in HFD-DP and HFD-LP mice. At 4 weeks of HFD feeding, the time point just before commencement of the TRF regime, diurnal rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity was observed in the HFD mice. Therefore, we can conclude that the TRF prevented, rather than reversed, the HFD-obesity induced ablation of diurnal rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity (Kentish et al., 2016). Whether TRF can also reverse the HFD-induced ablation of diurnal rhythmicity in GVA mechanosensitivity (Kentish et al., 2016) remains to be determined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, diurnal rhythmicity in GVA responses to food-related stimuli can be entrained by food intake. Further, the loss of diurnal rhythmicity in GVA responses to mechanical stimulation can be prevented by TRF. Whether the loss of diurnal rhythmicity observed after chronic HFD feeding can be reversed by TRF remains to be determined, but could potentially provide additional support for TRF regimes in the treatment of obesity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC Project Grant 1046289 and Peter Doherty Fellowship 1091586 to S.J.K.).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Arble DM, Bass J, Laposky AD, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW (2009) Circadian timing of food intake contributes to weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17:2100–2102. 10.1038/oby.2009.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Schibler U (2011) Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell Metab 13:125–137. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv R, Policker S, Brody F, Bitton O, Haddad W, Kliger A, Sanmiguel CP, Soffer EE (2008) Circadian patterns of gastric electrical and mechanical activity in dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20:63–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Báez-Ruiz A, Escobar C, Aguilar-Roblero R, Vazquez-Martinez O, Díaz-Muñoz M (2005) Metabolic adaptations of liver mitochondria during restricted feeding schedules. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289:G1015–G1023. 10.1152/ajpgi.00488.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J. (2012) Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature 491:348–356. 10.1038/nature11704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JM, Kelly KA (1983) Antral control of canine gastric emptying of solids. Am J Physiol 245:G334–G338. 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.3.G334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray MS, Ratcliffe WF, Grenett MH, Brewer RA, Gamble KL, Young ME (2013) Quantitative analysis of light-phase restricted feeding reveals metabolic dyssynchrony in mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 37:843–852. 10.1038/ijo.2012.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Miu P, Panda S (2014) Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab 20:991–1005. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Overduin J (2007) Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest 117:13–23. 10.1172/JCI30227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U (2000) Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev 14:2950–2961. 10.1101/gad.183500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AJ, Tataroglu O, Menaker M (2005) Circadian effects of timed meals (and other rewards). Methods Enzymol 393:509–523. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93026-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan K, Sassone-Corsi P (2013) Metabolism and the circadian clock converge. Physiol Rev 93:107–135. 10.1152/physrev.00016.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar C, Díaz-Muñoz M, Encinas F, Aguilar-Roblero R (1998) Persistence of metabolic rhythmicity during fasting and its entrainment by restricted feeding schedules in rats. Am J Physiol 274:R1309–R1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette MU, Tischkau SA (1999) Suprachiasmatic nucleus: the brain's circadian clock. Recent Prog Horm Res 54:33–58; discussion 58–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J (2008) The meter of metabolism. Cell 134:728–742. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, Ellisman MH, Panda S (2012) Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab 15:848–860. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish SJ, Page AJ (2014) Plasticity of gastro-intestinal vagal afferent endings. Physiol Behav 136:170–178. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish SJ, Frisby CL, Kennaway DJ, Wittert GA, Page AJ (2013) Circadian variation in gastric vagal afferent mechanosensitivity. J Neurosci 33:19238–19242. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3846-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish SJ, Vincent AD, Kennaway DJ, Wittert GA, Page AJ (2016) High-fat diet-induced obesity ablates gastric vagal afferent circadian rhythms. J Neurosci 36:3199–3207. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2710-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010) Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 8:e1000412. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Królczyk G, Zurowski D, Dobrek Ł, Laskiewicz J, Thor PJ (2001) The role of vagal efferents in regulation of gastric emptying and motility in rats. Folia Med Cracov 42:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamia KA, Papp SJ, Yu RT, Barish GD, Uhlenhaut NH, Jonker JW, Downes M, Evans RM (2011) Cryptochromes mediate rhythmic repression of the glucocorticoid receptor. Nature 480:552–556. 10.1038/nature10700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Qiao X, Chen JD (2004) Vagal afferent is involved in short-pulse gastric electrical stimulation in rats. Dig Dis Sci 49:729–737. 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000030081.91006.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS (2004) Mammalian circadian biology: elucidating genome-wide levels of temporal organization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 5:407–441. 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.175925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonogaki K, Nozue K, Oka Y (2007) Social isolation affects the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes in mice. Endocrinology 148:4658–4666. 10.1210/en.2007-0296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Martin CM, Blackshaw LA (2002) Vagal mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in mouse stomach and esophagus. J Neurophysiol 87:2095–2103. 10.1152/jn.00785.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergast JS, Branecky KL, Yang W, Ellacott KL, Niswender KD, Yamazaki S (2013) High-fat diet acutely affects circadian organisation and eating behavior. Eur J Neurosci 37:1350–1356. 10.1111/ejn.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas-Latre A, Eckel-Mahan K (2016) Interdependence of nutrient metabolism and the circadian clock system: importance for metabolic health. Mol Metab 5:133–152. 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser AM, Boulos Z, Terman M (1981) Circadian organization of food intake and meal patterns in the rat. Physiol Behav 27:33–39. 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90296-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudic RD, McNamara P, Curtis AM, Boston RC, Panda S, Hogenesch JB, Fitzgerald GA (2004) BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PLoS Biol 2:e377. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahar S, Sassone-Corsi P (2012) Regulation of metabolism: the circadian clock dictates the time. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23:1–8. 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler U, Ripperger J, Brown SA (2003) Peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals: time and food. J Biol Rhythms 18:250–260. 10.1177/0748730403018003007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara Y, Aoyama S, Shibata S (2017) The mammalian circadian clock and its entrainment by stress and exercise. J Physiol Sci 67:1–10. 10.1007/s12576-016-0450-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout DL, King SA, Bernstein PA, Halberg F, Cornelissen G (1991) Circadian variation in the gastric-emptying response to eating in rats previously fed once or twice daily. Chronobiol Int 8:14–24. 10.3109/07420529109063915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek FW, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, Lin E, Ivanova G, McDearmon E, Laposky A, Losee-Olson S, Easton A, Jensen DR, Eckel RH, Takahashi JS, Bass J (2005) Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian clock mutant mice. Science 308:1043–1045. 10.1126/science.1108750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Tomasi D, Backus W, Wang R, Telang F, Geliebter A, Korner J, Bauman A, Fowler JS, Thanos PK, Volkow ND (2008) Gastric distention activates satiety circuitry in the human brain. Neuroimage 39:1824–1831. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]