Abstract

In 2016, the government of Cameroon, a central African country heavily reliant on wood fuel for cooking, published a Masterplan for increasing primary use of LPG from 20% to 58% of households by 2035. Developed via a multi-sectoral committee with support from the Global LPG Partnership, the plan envisages a 400 million Euro investment program to 2030, focused on increasing LPG cylinder numbers, key infrastructure, and enhanced regulation. This case study describes the Masterplan process and investment proposals and draws on community studies and stakeholder interviews to identify factors likely to impact on the planned expansion of LPG use.

Keywords: LPG market development, investment, regulation, affordability, safety

BACKGROUND

Cameroon is one of several Sub-Saharan African countries whose governments have set ambitious goals for scaling-up use of LPG as a cooking fuel (Van Leeuwen, Evans, & Hyseni, 2017). For Cameroon, the target is to take primary LPG use from around 15% in 2014 to 58% by 2035, resulting in 18 million more Cameroonians gaining access (GLPGP, 2016c). Several reasons underlie this decision, including forest protection, health improvement, and economic and energy development in line with regional policy (CEEAC, 2014).

With the support of the Global LPG Partnership (GLPGP – see Box 1), the government had by September 2016 approved a detailed ‘LPG Masterplan’ for investment and regulatory enhancement, designed to meet the target. Implementation of the plan is now underway, led by a multi-sectoral ‘Investment Committee’ established in early 2017.

Box 1: The Global LPG Partnership.

The GLPGP is ‘a United Nations (UN)-backed Public-Private Partnership formed in 2012, under the UN Sustainable Energy for All initiative, to aggregate and deploy needed global resources to help developing countries transition large populations rapidly and sustainably to liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) for cooking.’

[Source: www.glpgp.org]

Contemporaneously with this national level planning, a programme of mixed-methods, community-based research, the ‘LPG Adoption in Cameroon Evaluation’ (LACE) studies, were being conducted in rural and peri-urban areas of the South West region, near Limbe (Pope, 2017a, 2017b). The objectives were to (a) determine enablers and barriers to adoption and greater use of LPG for cooking, (b) test interventions (consumer micro-loans for start-up costs, pressure cookers for saving gas) to mitigate these barriers, and (c) assess health risks through air pollution measurement.

Cameroon is the first sub-Saharan African country to develop a comprehensive ‘Masterplan’ for rapid and substantial expansion of its LPG market. This case study describes the plan and its investment proposals and compares these with the population’s experiences of adopting and using LPG for cooking from the LACE studies and stakeholder interviews to make recommendations.

METHODS, SOURCES and APPROACH

We drew on a range of data sources, including national surveys and energy policy reports, Masterplan documentation, stakeholder interviews and the LACE studies, for which sources and methods are summarised below.

National and regional reports and secondary data

We obtained information on regional and national assessments of energy use, prospects, and policy, from the following reports in order to understand the context of the Cameroon LPG scale-up (Table 1).

Table 1:

Regional and national reports

|

Masterplan documentation

In order to describe the aims, drivers, process, recommendations, and implementation of the masterplan, we referred to the Cameroon LPG Masterplan Executive Summary (GLPGP, 2016a, 2016b)1,2, the Masterplan full report (not in the public domain and obtained from the GLPGP), and Investment Committee minutes (MINEE, 2017).

Qualitative interviews with key stakeholders, meetings, and field visits

GLPGP experts in sustainable LPG market development

In order to understand the role of the GLPGP and expertise brought to the Masterplan’s development, we undertook group and individual interviews (via conference calls, telephone, and correspondence) with six GLPGP staff between June and August 2017 (Box 2). These participants were selected for their knowledge of (i) the Cameroon and other early stage LPG markets, (ii) international policy and regulatory reform and (iii) the relationship between gender, poverty, and energy access.

Box 2: GLPGP staff interviewed.

President and Chairperson

Chief Financial Officer

Chair of International Institutions

Chair of the Policy, Regulation & Development Advisory Group

Director of Research, Monitoring & Evaluation

Country Director for Cameroon.

Stakeholders in Cameroon

Qualitative methods were used to understand the processes involved in developing the national LPG Masterplan and key factors likely to influence market growth in Cameroon, including: key informant interviews; informal discussions; observations; and field visits to the LACE research project sites. Field work took place between 28th August and 6th September 2017. Interview participants were purposively recruited from research group contacts within the fields of energy, LPG supply, and public health. We held seven face-to-face, semi-structured interviews with representatives from a government ministry and a public-private partnership involved in LPG scale-up, both sitting on the national Masterplan Committee; financial and microfinance institutions at national and regional levels; and community leaders. Interviews lasted approximately one hour and were conducted in French or English. We held informal discussions with five other stakeholders involved in LPG scale up; a marketer, a cylinder supplier, and a financial institution and NGO supporting community micro-loans. Discussions centred on household energy and LPG use in Cameroon, and the Masterplan process and plans. We also visited the LACE study sites and an LPG filling plant to observe infrastructure relating to oil production, importation, refinery, bulk storage, and distribution.

We digitally recorded, transcribed, and translated all interviews, and data were anonymised. We analysed interview transcripts, meeting records and field notes thematically (Braun & Clarke, 2014), and organised findings using Framework analysis (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003).

LACE studies

The LACE studies were conducted in peri-urban and rural communities near Limbe, SW Cameroon, January 2016 to October 2017, Table 2:

Table 2:

Overview of aims and main components of the LACE studies (2015-2017)

| Phase | Main aims | Components of study |

|---|---|---|

| LACE-1 2015-2016 |

|

|

| LACE-2 2016-2017 |

|

|

Full methodologies are available in on-line protocols for LACE-1 (Pope, 2017b) and LACE-2 (Pope, 2017a). A comparison of LACE and national data (MINPROFF, 2012; NIS, 2014, 2015a), available on request, showed that the LACE sample had lower poverty levels than in the country overall, but that education, reliance on solid fuel use and access to clean water were similar.

Synthesis

A national LPG market can be viewed as a ‘complex system’ (Jackson, 2003). Logic models offer a way of describing these as part of evaluation, and we have previously described one such model (Rosenthal et al., 2017). We developed this from literature review (Puzzolo, Pope, Stanistreet, Rehfuess, & Bruce, 2016; Rehfuess, Puzzolo, Stanistreet, Pope, & Bruce, 2014) and experience from the GLPGP. For this case study, we used the model to systematically organise information and compare the Masterplan recommendations against the issues, challenges and opportunities identified from the other sources.

Primary data collection through stakeholder interviews was covered by LACE-1 ethical approval obtained from the Cameroon National Ethics Committee (2015/12/653/L/CNERSHP/SP) and the University of Liverpool (RETH001035).

FINDINGS

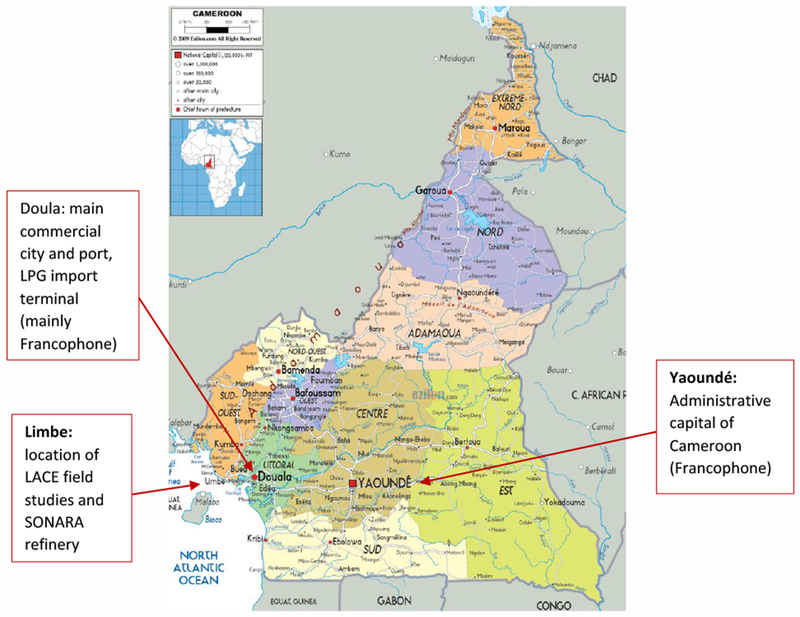

Situated in central Africa, Cameroon has a population of 23.9 million (2016), expected to reach around 31 million by 2030 and 34.5 million by 2035 (MINEE, 2015). Most of the population are Francophone (including the administrative centre, Yaoundé), the rest Anglophone; Douala is the main commercial city and port (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Map of Cameroon showing location in central Africa and coastal border with the ports of Douala and Limbe, and the capital city of Yaoundé.

Source: https://alexincameroon.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/political-map-of-cameroon.gif?w=1412

Cooking fuel and household energy:

Reliance on solid fuels for cooking is high in Cameroon, although fell from 82.4% in 2001 to 65.0% in 2014 but remains very high in rural areas (87.5%) compared to urban areas (36.8%) (NIS, 2015a). In 2015 the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources (MINEE) reported that 25.1% of the population ‘had access to’ (this phrase is not further defined) LPG in 2014, Table 3 (MINEE, 2015).

Table 3:

Percentage of total, rural and urban homes having access to LPG in 2001, 2007 and 2014

| Setting | 2001 | 2007 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 34.6 | 37.0 | 48.8 |

| Rural | 1.9 | 2.5 | 5.2 |

| National | 13.4 | 15.3 | 25.1 |

Source: NIS (Cameroon)

The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) reported that ‘primary use’ of LPG for cooking was 17.5% in 2011 (DHS, 2012). Data on exclusive LPG use is not yet available from national population surveys, but local (Limbe area) data on mixed and exclusive LPG use in peri-urban and rural households from the LACE studies is reported below.

Government aim for national LPG scale up

The aim of the LPG scale-up in Cameroon is stated as follows:

‘Within the framework of aspiring to become an emerging nation by the year 2035, the government of Cameroon intends to extend the availability, access, and use of Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) made up of gas and /or propane for cooking and other uses to 57.8% of the population on an economically sustainable basis.’

[Source: LPG Masterplan Executive Summary]

The drivers are ‘to increase access to clean energy resources, improve public health, reduce deforestation and the adverse effects of climate change caused by deforestation, while increasing economic development’. The choice of LPG for achieving these goals, if accessible and affordable to a majority of the population, is supported by a range of evidence. Laboratory testing by the USEPA reported that LPG meets (or exceeds) ISO Tier 4 of the ISO International Workshop Agreement on stove standards (GACC, 2012; ISO, 2012) for emissions of PM2.5 and CO (Shen et al., 2017). Use of LPG can also reduce climate warming emissions compared with traditional and many improved biomass stoves (especially where a substantial proportion of biomass fuel is harvested non-renewably), and protect forests (Bruce, Aunan, & Rehfuess, 2017).

Masterplan market assessment and investment proposals

During Masterplan development, GLPGP assessed the Cameroon LPG market. Several strengths were noted, including the cylinder re-circulation model (cylinders are owned by marketers who are responsible for checking and replacement), and relatively good regulation. One weakness, however, is the dominance of cylinder wholesalers not loyal to a specific marketer’s brand, thereby disrupting the process by which an empty cylinder, when exchanged for a refill, should always go back to the marketer for safety checking. Other factors impacting prospects for market expansion are reported in Box 3.

Box 3: GLPGP/Masterplan assessment of LPG market in Cameroon.

‘The GLPGP market evaluation found that Cameroon, when compared with the characteristics of developed LPG markets, has weakness in the ‘offer’ of LPG cylinders and the distribution network geared at resupplying filled cylinders. The growth in the number of cylinders in circulation in Cameroon barely increased faster than the population. If such a trend continues, considering the expected growth of the population, it would take over 50 years to achieve the government’s objectives. Looking at the breakdown by region, Douala and Yaounde regions accounted for around 87-88% of consumption over the last 15 years. The other regions represent about 13% of consumption and grew at the same rate, thereby demonstrating the ability of stakeholders to develop use of LPG, despite the difficulties involved. The LPG offer equally includes logistics capacity (filling plant and bulk LPG transportation) which has reached saturation in some places (Douala and Yaoundé) but less so in areas lacking cylinders and a network of sales outlets with reliable distributors.’

Source: [edited from] GLPGP/Cameroon LPG Masterplan Executive Summary

The main ‘instrument’ for development of the Masterplan was a multi-sectoral Committee lead by Ministry of Energy and Water Resources (MINEE) and facilitated and coordinated by GLPGP, with funding from the EU Infrastructure Fund and the German Development Bank, KfW. This had broad representation, as listed in Box 4.

Box 4: Ministries and partners represented on the Cameroon LPG Masterplan Committee.

Ministry of Energy and Water (MINEE)

Ministry of Industry, Mines and Technological Development (MINIDT)

Ministry of Environment, Nature Protection and Sustainable Development (MINEDEP)

Ministry of Public Health (MINSANTE)

Ministry of Commerce (MINCOMMERCE)

Ministry for promotion of women and families (MINPROFF)

National Oil Refining Society (SONARA)

SCDP (Société Camerounaise des Dépôts Pétroliers)

GPP (Groupement Professionnel du Petrole), a syndicate bringing together professionals in the downstream sector.

National Hydrocarbon Society (SNH)

CSPH (Caisse de Stabilisation des Prix des Hydrocarbures)

Sustainable Energy for All (SEforAII)

Global LPG Partnership (GLPGP)

Four committee sub-groups addressed: pricing and transport; supply chain and filling; distribution and licensing; and safety and norms. Another sub-group liaised with the private sector, dealing with finance and communications.

Work was initiated in April 2015, and the plan was officially announced in December 2016. The first meeting of the Investment Committee, responsible for implementation, took place in May 2017.

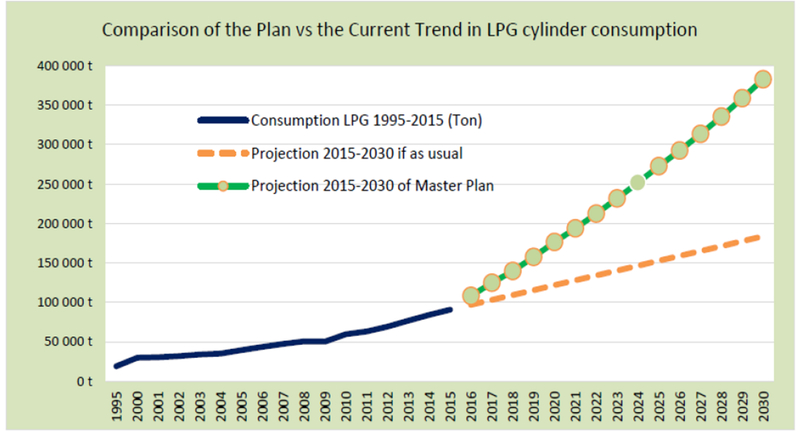

The Masterplan recommendations are summarised in Table 4 (GLPGP, 2016b). Central to these proposals is the need to markedly increase the number of LPG cylinders, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 4:

Summary of Cameroon LPG Masterplan recommendations

|

Figure 2:

Comparison of the increase in cylinders proposed in the Masterplan, compared with the existing trend (with projection)

Source: Cameroon LPG Masterplan Executive Summary

To achieve the planned LPG market expansion, investment of around 400 million Euros was estimated by GLPGP, Table 5.

Table 5:

Summary of proposed investments in the Cameroon LPG market to 2030

| Component | Specific requirement | Million Euro |

|---|---|---|

| Cylinders | Additional 7 million 12.5 kg cylinders | 243.0 |

| Logistics | Additional filling and storage capacity of filling plants | 85.9 |

| Cylinder re-testing, certification, and painting in filling plants | 2.4 | |

| Additional capacity of the Kribi import terminal | 54.0 | |

| Road and rail transport tankers | 17.5 | |

| Total | 402.8 | |

Source: based on Cameroon LPG Masterplan Executive Summary (GLPGP, 2016b)

Stakeholder and LACE study findings

In this section, we report findings from the expert and stakeholder interviews, and the LACE studies carried out in peri-urban and rural communities near Limbe, with implications for scaling up LPG for cooking.

Use of LPG in homes and extent of stacking

Among 1334 peri-urban homes, the LACE census survey found solid fuel (almost exclusively wood) was the primary fuel for 38.5%, and LPG the primary fuel for 57.6%. Only 9.5% did all cooking on LPG, 68.7% did some (i.e. they ‘stacked’) and 21.8% used no LPG.

Among the 243 rural homes, solid fuel (mostly wood) was the primary fuel for 81.1%, and LPG was the primary fuel for 15.6%; very few (1.2%) did all cooking on LPG, 28.8% did some, and 70% used no LPG. So, even in an area that has lower levels of poverty than nationally, stacking was observed for most LPG users, including peri-urban.

Most households reporting any LPG use obtained one 12.5 kg refill every 1-2 months, with less than 10% using more. Exclusive users obtained a mean of 7.6 refills/year, corresponding to 21 kg per capita/year allowing for household size and consistent with consumption for near exclusive use in other countries. Primary LPG users obtained a mean of 6.7 refills per year (14.7 kg per capita/year), and mixed LPG/biomass users 5.5 refills per year (12.2 kg per capita/year), insufficient for exclusive LPG use for cooking.

About 20% of participants kept more than one LPG cylinder from different marketers (i.e. different brands) in their home, a strategy for making it easier to obtain a refill when supplies from one marketer became unavailable.

Aspirations to use LPG and affordability

Among non-users, 75% of rural and 89% of peri-urban respondents said they would like to use LPG in the future. Their main barriers were the initial cost (50.3% rural, 54.6% peri-urban) and safety concerns (14.2% rural, 23.6% urban), while reasons for wanting to switch to LPG were ease of cooking (22.1%) and convenience and pleasure (31.2%). Some 74% of peri-urban LACE respondents thought that the refill cost was expensive or very expensive, and slightly more (82%) among rural respondents.

Options for financial support

Two approaches are available for helping consumers with LPG costs, namely fuel subsidies and loans. Cameroon subsidises LPG for all users to maintain a steady price, with a 12.5 kg refill costing 6,500 CFA (US$ 11.50) or US$ 0.94/Kg as of December 2017. This subsidy is expected to continue, but with more frequent adjustments reflecting changes in international prices. A subsidy targeted at poorer households is not proposed (see below), although the recommendation to harmonise prices nationally would assist rural areas, who currently pay more than users closer to depots.

A microloan pilot project, jointly managed by GLPGP and MUFFA, offered LPG start-up kits (12.5 kg full cylinder, cooker, hose, and regulator) through a loan of approximately US$ 94 (including a US$ 14 security deposit) repayable over six-months, to 150 self-selected non-LPG using homes in the LACE study area. For this initial pilot, interest was not charged. Evaluation, a component of the LACE-2 study, found that by November 2017, 88.7 % of loans had been repaid in full (corresponding to 94.3% of loaned capital), although analysis of cooking patterns is awaited. The scheme was well-accepted and has already been taken up by another local community.

Stakeholder interviews found considerable interest in consumer finance, with microloan schemes offered by the women’s cooperative to purchase LPG equipment being seen as having benefits for women and their children:

‘So, the children aspect is a consequence of the empowerment of the women. […] if the woman has gas at home, she has more time to spend with the children. She has more time to do her business […] instead of going out to look for energy […]. Those are some of the social benefits.’

[National Bank].

The loan pilot did also encounter challenges, according to the financial cooperative and the National Bank supporting it, including late recovery of repayments from some participants. Repayment issues were usually explained in relation to wider constraints, including competing financial demands; and cylinder theft5 which left the victim without gas, unable to reclaim the cylinder deposit, but still liable to repay the loan:

‘Survival comes first. Taking the loan is easy. […] Reimbursement is difficult. […] These are small credits that they neglect. If we give them credits, we have to chase them up a lot. People have many problems. It just takes a microloan woman to fall ill, paralysed [and] she can’t pay.’

[Women’s Financial cooperative]

‘it’s easy to steal the cylinders. People steal them and sell them elsewhere. […] Sometimes some say: ‘Someone stole my cylinder’, but they still owe the repayment. The cylinder is like a guarantee. If they don’t pay, they have to give it back. In my case, someone stole two gas cylinders from my house [prior to the microfinance scheme].’

[Women’s Financial cooperative]

Building on pilot study experience, the scheme is being extended across ten other sites nationally involving 800 homes, all of whom will be members of community banks (MUFFA or MC26) with a track record of paying back loans taken out for other purposes. There will be a 15% annual interest rate to ensure sustainability. The National Bank hosting the LPG microloan project is also encouraged by success of the pilot and, as a bank keen to support social development, would contribute to national expansion.

‘[…] we started with the [rural development MFIs7]. For me it’s a very good thing, because […] it’s a way for us […] to participate in the development and in resolving some of the social problems. […] I will be happy to know that my [rural development MFI] helps in propagating the use of gas. For me, it’s good also for our image. It’s important. So, I was very happy when I knew that the pilot phase was successful.

[National Bank].

GLPGP experts said that a targeted subsidy had not been discussed for Cameroon, adding that this ‘typically occurs at a later stage of market development’. Moreover, they felt the lack of robust data and digital systems to determine and prove eligibility, and potential public disapproval of reallocating the existing general subsidy to benefit specific groups, would be barriers. That said, the ‘Give it up’ campaign in India8 has shown one way in which this can be tackled.

The national bank representative concurred, also citing as a barrier, the lack of records of income and other indicators of socioeconomic status, and of personal identity documentation. A model which subsidised micro-entrepreneurs to offer reduced prices to lower-income consumers was thought more feasible but would require significant regulation to prevent abuse.

LPG access and supply

LACE data showed a relationship between distance travelled to obtain LPG refills and LPG use, and the actual distances were perhaps surprising. Around one-quarter (26.5%) of exclusive LPG users travelled from 1 to more than 5 km to obtain refills (16.3% more than 5 km). This percentage rose to 33.4% in primary LPG users, and 39.1% in mixed LPG/biomass users (one-quarter more than 5 km).

LPG safety practices and perceptions

One striking LACE finding was that many peri-urban (73%) and rural (80%) households when asked about safety perceptions thought LPG fuel was ‘dangerous’ or ‘very dangerous’. There was a strong inverse relationship between the degree to which users felt LPG was dangerous and LPG use, i.e. whether LPG was the primary or secondary fuel, or not used. Stakeholders recognised that ensuring public safety and reassuring the public about safe LPG use was vital for LPG market expansion.

‘The key issues […] are […] manipulation of the cylinders themselves and the hoses. […] Users don’t connect the hose tightly to the regulator, so you may have some leakages.’ [GLPGP Cameroon p.8]

This interviewee suggested it was important to visit households to check safe cylinder use, to repeat safety information and to offer advice, particularly among households with poor literacy levels, although a mechanism for providing this support remains to be identified.

Awareness of LPG benefits to health

It was reported that health professionals did not routinely ask patients with respiratory and other HAP-related diseases, about the fuel they used for cooking. There is currently no public education programme on the health and safety risks from cooking on open fires, although there are now government plans to raise public awareness of the health benefits of using clean cooking fuels and provide guidelines to regional public health departments. Provision of health education and training on safe use of LPG cylinders for cooking were felt to be a shared responsibility:

I think that is the responsibility of several partners [including] the marketers. When a marketer sells their product, they should pass on instructions at that point to the consumer. And [it is the responsibility] of the government to educate the public about the risks’. [Government Ministry]

Convenience and meeting cooking needs

Several stakeholders thought local food preferences, including for smoked and chargrilled meat and fish over an open fire, would preclude exclusive cooking with LPG in Cameroon. Around 80% of LACE households across peri-urban and rural settings believed that cooking with LPG was fast or very fast, and around half overall (45% rural, 59% peri-urban) thought that LPG was ‘OK or easy to use’ for cooking most foods. The open fire was used to cook ‘hard’ traditional foods like ‘fufu’, beans and corn-chaff, though the main reason was the large amount of gas needed (the rationale for the pressure-cooker intervention study in LACE-2). Over 90% of households in both settings thought LPG was a clean fuel, was convenient because it could be used inside the home and freed up time to do other activities.

Impact of LPG use on health risks

Data from the LACE-1 study on PM2.5 kitchen concentrations and exposure for women (cook) and child (<5 years of age), comparing exclusive LPG users and exclusive biomass users are shown in Table 6.

Table 6:

Median (IQR) values for 24-hr average PM2.5 in μg/m3, numbers (n) and p-values (Wilcoxon rank sum test) for differences between LPG (exclusive and primary) and biomass users.

| Measure | LPG primary users | Biomass exclusive users | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kitchen | 21.1 (13.9, 41.6) n=67 | 447.9 (164.2, 905.1) n=55 | <0.0005 |

| Woman | 14.0 (9.5, 23.1) n=67 | 46.9 (26.4, 85.5) n=61 | <0.0005 |

| Child | 13.3 (7.0, 19.5) n=60 | 27.1 (15.0, 50.8) n=56 | <0.0005 |

Source LACE-1 Study

There were large, statistically significant differences in kitchen concentrations of PM2.5 between primary LPG and exclusive biomass use. In addition, exposures in women and young children were significantly lower in households using LPG, implying lower health risks. The relatively low levels of PM2.5 exposure in the biomass users is likely to result from women and children spending only a part of their time in the kitchens when fires are lit, especially as data were collected in the dry season, when people spend more time outdoors.

There was weak (marginally non-significant) evidence from the LACE household survey responses of a relationship between LPG use and some respiratory symptoms (wheezing, morning phlegm), stronger evidence of a link with eye irritation, but not with headaches. There was strong evidence of fewer burns in women in the exclusive LPG group (compared to the others), although not for children.

LACE qualitative interviews found that health problems like headaches, chest pain and breathing problems while cooking were overwhelmingly reported by women who cooked solely with biomass; mixed users perceived that their health problems were only caused when cooking with a three-stone fire. Health problems amongst biomass users were discussed by the women as justification for switching to LPG stoves. These are important findings as they show that women do recognise health problems associated with the use of traditional biomass fuels.

Discussion

This case study presents a ‘baseline’ description of the Cameroon LPG Masterplan, the first of its type in Africa, and a response to the government’s policy goal of scaling up LPG access from less than 20% to almost 60% of the population by 2035. The plan is based on an assessment of the current market, and experience from other developing country settings of what is needed in terms of investment and regulation. A 400 million Euro investment programme to 2030 is proposed, with a major focus on increasing the number of cylinders to meet expanded demand, as well as infrastructure, transport and retail enhancement, and improved market regulation.

A priority for implementation has been to develop suitable mechanisms to secure and manage this new investment. For cylinders, a goal is to reduce the price to both marketers (who need to purchase large numbers of new cylinders), and to end-users (benefitting from a lower deposit price). As of May 2018, options are under discussion between government, marketers, national LPG market agencies, and the GLPGP, designed to ensure returns on investments, with guarantees where required.

The Masterplan proposals would, on the face of it and over time, appear to address the major supply-side challenges and barriers to adoption and more exclusive use reported by LACE study participants and stakeholders. Cylinder deposit prices have already been reduced, and refill costs would be harmonised across the country helping rural areas, although not actually reducing fuel costs overall. Safety is highly dependent on market regulation and use of the cylinder recirculation model with branded cylinders (already in place), and safety can be expected to improve further if the proportion of distribution that is brand-loyal is increased thereby ensuring cylinders are returned to the marketer for checking.

Some key demand-side factors would appear to need further attention. The affordability of LPG, particular for the start-up costs, was an important concern in the LACE studies. The GLPGP/MUFFA ‘Bottled gas for better life’ microloan pilot has been viewed positively by the community, loan organisations, the national bank with oversight responsibilities for community loans in Cameroon, and recently also the national government. This experience has informed an expanded scheme being prepared for implemented across five regions of the country. There is thus optimism about prospects for scaling-up loans, so long as these are managed through membership of community banks and realistic interest is charged to cover servicing costs. Measures to address the widespread public perceptions (from the LACE study) that LPG is not safe are not directly addressed in the masterplan proposals, although this may be an important factor in limiting demand in Cameroon together with lack of sufficient cylinder inventory. The role of health sector in increasing demand for LPG is not prominent in the Masterplan, and this should be enhanced, for example by in-service training (continuing medical education).

Because the LPG market is a complex system (Rosenthal et al., 2017), and the regulatory changes and investments recommended by the Masterplan will impact on many critical components, determining the extent and timing of impacts of these proposals is not straightforward. For example, the planned improvements in supply, distribution, and retail access of LPG, are likely to have far-reaching effects on how people across the country view this fuel in the coming years and the desirability of adopting this fuel, or using it more, but the extent and speed of this change in perceptions and hence demand is hard to gauge.

Contextual factors in Cameroon, including population growth (to reach around 34.5 million by 2035), widening poverty gaps, below-target per capita GDP growth and a ‘hesitant’ commercial sector (NIS, 2014), may present challenges for LPG market expansion. Additional uncertainties may arise from forthcoming presidential elections in 20189, and ongoing tension between the Francophone and Anglophone regions10. On the other hand, the existing cylinder recirculation model and good regulation for an early-stage market, are very important, positive features on which to build.

LPG in Cameroon is an ‘early-stage’ market (4.0 kg/capita in 2016) that has been growing slowly but steadily. The new strategy is just starting implementation, so monitoring and evaluation will be important for the next 5-10 years and will provide a very valuable opportunity to assess how effective the specific proposals are in expanding adoption and use of LPG for cooking. The Masterplan includes a number of ‘key performance indicators’ (e.g. number of cylinders in circulation; LPG consumption in kg per capita, etc.), and a new cross-ministry entity consolidating oversight of the LPG sector, including monitoring progress on Masterplan implementation, is being considered. Further independent evaluation work would provide valuable learning for the international community.

Highlights:

In 2014, the government of Cameroon announced its intention to increase use of LPG for cooking from less than 20% to nearly 60% of households by 2035.

With input from the Global LPG Partnership, a LPG Masterplan was developed which proposed investment of 400 million Euro to 2030, for an additional 7 million LPG cylinders and strengthening key importation, storage, transport, and retail infrastructure.

Community and stakeholder perspectives identify concerns about affordability, safety, and ability to cook traditional foods which may need further attention, and support an enhanced role for the Health Sector in promoting a clean fuel.

Acknowledgments:

This work was carried out with support from the NIH led Clean Cooking Implementation Science Network (ISN) with funding from the NIH Common Fund Global Health program

Funding:

The case study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes for Health Implementation Science Network.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

[French version of Executive Summary]: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5633c4c2e4b05a5c7831fbb5/t/597a3870d2b857fc8796219f/1501182066543/Cameroun+Executive+Summary+du+Master+Plan+GPL+-+FR.pdf

[English version of the Executive Summary]: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_799OzSup8bU1adnUzN0RHMVU/view

MUFFA: Mutuelle Financière des Femmes Africaine (The African Women’s Mutual Finance), is a microfinance institution set up to offer financial services to low income women and women of the informal sector and urban areas.

There were no recorded cylinder thefts form the LACE-2 evaluated pilot scheme near Limbe, and this comment likely refers to the respondent’s own experience and concerns.

MFI: Micro-finance institution

LPG subsidy ‘Give it up’ campaign in India http://www.givitup.in/about.html

2018 Presidential elections, see for example: https://lcclc.info/index.php/2017/05/09/cameroon-2018-presidential-elections-already-11-declared-candidates/

Tension between Francophone and Anglophone regions, see for example: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-41442330

References

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being, 9, 26152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Aunan K, & Rehfuess E (2017). Liquefied Petroleum Gas as a Clean Cooking Fuel for Developing Countries: Implications for Climate, Forests, and Affordability. Materials on Development Financing - Volume 7: KfW Development Bank. Retrieved from https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/PDF/Download-Center/Materialien/2017_Nr.7_CleanCooking_Lang.pdf

- CEEAC, C. (2014). CEEAC and CEMAC White Paper: Regional Policy for Universal Access to Modern Energy Services and Economic and Social Development 2014 – 2030. Final Draft. [Politique régionale pour un accès universel aux services énergétique modernes et le développement économique et social 2014 – 2030]. Retrieved from https://www.se4all-africa.org/fileadmin/uploads/se4all/Documents/News___Partners_Docs/ECCAS_CEMAC_livre_blanc_energie_2014.pdf

- DHS. (2012). Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples, 2011 [Demographic and Health Survey on Multiple Indicators, 2011]. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR260/FR260.pdf

- GACC. (2012). ISO International Workshop Agreement. Technology and Fuels Standards Retrieved from http://cleancookstoves.org/technology-and-fuels/standards/ [Google Scholar]

- GLPGP. (2016a). [Executive Summary du MASTER PLAN GPL du CAMEROUN - VERSION FINALE - Présenté au « AD-HOC COMITE GPL » du 31 Aout 2016, à Yaoundé] Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5633c4c2e4b05a5c7831fbb5/t/597a3870d2b857fc8796219f/1501182066543/Cameroun+Executive+Summary+du+Master+Plan+GPL+-+FR.pdf

- GLPGP. (2016b). Executive Summary of The LPG Master Plan for Cameroon, presented at the LPG Ad Hoc Committee Meeting of 31 August 2016, in Yaoundé New York: The Global LPG Partnership Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_799OzSup8bU1adnUzN0RHMVU/view. [Google Scholar]

- GLPGP. (2016c). The LPG Master Plan of Cameroon, presented at the LPG Ad Hoc Committee of the 31st of August 2016, at MINEE, in Yaoundé (MINEE, Trans.) New York: The Global LPG Partnership. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. (2012, February 2012). ISO/IWA 11:2012 (en) Guidelines for evaluating clean cookstove performance. International Workshop Agreement IWA 11 Retrieved from https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:iwa:11:ed-1:v1:en [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MC (2003). Systems thinking: creative holism for managers. New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- MINEE. (2015). The Energy Situation in Cameroon [Situation Energétique du Cameroun]. Yaounde, Cameroon: MINEE. [Google Scholar]

- MINEE. (2017). Meeting Minutes: First meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee tasked with the development and structuring of a finance model for LPG Master Plan investments to develop the LPG market in Cameroon held on 10 May 2017 MINEE. Yaoundé. [Google Scholar]

- MINPROFF. (2012). Women and Men in Cameroon in 2012: A Situational Analysis of Progress in Relation to Gender [Femmes et Hommes au Cameroun (2012): Ministère de la Promotion de la Femme et de la Famille (MINPROFF)] (N. I. o. Statistics Ed.). Yaoundé, Cameroon: MINPROFF. [Google Scholar]

- NIS. (2014). Presentation of the First Results of the Fourth Cameroon Household Survey (ECAM 4) of 2014 Yaounde, Cameroon: National Institute of Statistics, Cameroon. [Google Scholar]

- NIS. (2015a). National Report on the Millennium Development Goals in 2015. Yaounde, Cameroon: National Institute of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- NIS. (2015b). National Report on the Millennium Development Goals in 2015: Synthesis Note. Yaounde, Cameroon: National Institute of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Pope D (2017a). The LPG Adoption in Cameroon Evaluation-2 Study (LACE-2). Enhancing adoption and use of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG): an implementation science approach to understanding key determinants and impacts of local interventions to address financial constraints. Optimising upscale of improved energy technologies. Retrieved from https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/psychology-health-and-society/research/energy-air-pollution-health/lace-2/

- Pope D (2017b). The LPG Adoption in Cameroon Evaluation (LACE) Study 1. Scaling adoption and sustained use of LPG as a clean fuel in Cameroon. Energy, Air Pollution and Health Research. Retrieved from https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/psychology-health-and-society/research/energy-air-pollution-health/lace-1/ [Google Scholar]

- Puzzolo E, Pope D, Stanistreet D, Rehfuess EA, & Bruce NG (2016). Clean fuels for resource-poor settings: A systematic review of barriers and enablers to adoption and sustained use. Environ Res, 146, 218–234. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfuess EA, Puzzolo E, Stanistreet D, Pope D, & Bruce NG (2014). Enablers and barriers to large-scale uptake of improved solid fuel stoves: a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect, 122(2), 120–130. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, & Lewis J (Eds.). (2003). Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal J, Balakrishnan K, Bruce N, Chambers D, Graham J, Jack D, … Yadama G (2017). Implementation Science to Accelerate Clean Cooking for Public Health. Environ Health Perspect, 125(1), A3–a7. doi: 10.1289/ehp1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Hays M, Smith K, Williams C, Faircloth J, & Jetter J (2017). Evaluating the Performance of Household Liquefied Petroleum Gas Cookstoves Environ Sci Technol, doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen R, Evans A, & Hyseni B (2017). Increasing the Use of Liquefied Petroleum Gas in Cooking in Developing Countries. Live Wire, World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26569 [Google Scholar]