Abstract

Background

The number of medical marijuana patients is increasing. This increase raises important concerns about how medical marijuana use may affect parenting.

Methods

Thirty-two adult medical marijuana patients participated in focus groups. The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. The transcriptions were coded by a team that met regularly to resolve coding differences. Codes related to parenting were used to develop a conceptual model for this manuscript.

Results

Six of 11 participants who identified being parents reported that using marijuana helped them to be calmer with their children and to manage difficult emotions related to parenting. At the same time, most medical marijuana patients did not want their children to use marijuana. Their concerns about their children led to different strategies related to storing medical marijuana securely and how to communicate with children about medical marijuana use.

Conclusions

These findings show that many medical marijuana patients are concerned about their children using marijuana and may be open to strategies to addressing this issue with their children. These findings also show that some medical marijuana patients may benefit from alternative strategies for managing difficult emotions related to parenting.

Keywords: Adolescents, marijuana, medical, parenting

BACKGROUND

As of March 2013, eighteen states 18 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana (Conaboy, 2012). Not including California, Hawaii and Washington, for which data are not available, there are almost 300,000 medical marijuana patients in the United States (Bowles, 2012). Various countries including Canada, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom also allow for medical marijuana use (New York Times, 2003). In addition, more states and countries are considering medical marijuana (Chicago Tribune, 2012).

Colorado medicalized marijuana in 2000, allowing patients an affirmative legal defense for using and possessing marijuana after obtaining a physician’s recommendation and completing a state application (Colorado State Constitution, 2001). Officially, Colorado accepts eight qualifying conditions for medical marijuana use: cachexia, cancer, glaucoma, human immunodeficiency virus, muscle spasms, nausea, pain, and seizures (Colorado State Constitution, 2001). However, there are reports of medical marijuana being recommended for various other reasons such as psychiatric disorders (Thurstone, 2010). Following federal announcements in 2009 that enforcement of aspects of the Controlled Substances Act would take a low priority in states with legal medical marijuana, Colorado saw a large increase in the number of medical marijuana patients (Stout & Moore, 2009). For example, in January 2009, there were 5,051 patients but by December 2010 there were 116,198 patients, which corresponds to 3.1% of Colorado’s adult population (United States Census, 2012).

The growth in the number of medical marijuana patients increases the odds that there will be parents who use medical marijuana. Parental marijuana use, in turn, may have an important impact on children and adolescents. For example, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health show that 21.9% of children (12–25 years) with a parent who used marijuana in the last year also had past year marijuana use compared to 12.7% for those whose parents did not use marijuana in the last year (Kandel et al., 2001). Marijuana intoxication also causes deficits in attention, coordination, information processing and reaction time while marijuana withdrawal symptoms include irritability, restlessness and depressed mood (Budney et al., 2004; Hall & Degenhardt, 2009). These effects may, in turn, also affect parenting behavior.

While we are not aware of research specifically assessing the impact of marijuana use on parenting, parental substance abuse, in general, is associated with child abuse and neglect. Data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study show that, compared to parents without a lifetime history of drug abuse or dependence, parents with a lifetime history of drug abuse or dependence are three times more likely to report a history of physically or sexually abusing their children and 10 times more likely to report a history of neglecting their children (Kelleher et al., 1994). In addition, at least half of reported cases of child abuse and neglect involve caregiver substance abuse (Curtis & McCullough, 1999; Murphy, Jellinek, Quinn, Smith, Poitrast, & Goshko, 1991). However, a major limitation of these studies is a lack of research focusing specifically on how marijuana may affect parenting.

Despite these concerns, there is little information about how medical marijuana use may affect parenting. An Op-Ed article in the New York Times suggests that medical marijuana use may improve a parent’s patience and calmness around children (Wolf, 2012). However, research in the medical literature is lacking. Such information would help health care providers counsel their patients who use medical marijuana. Agencies that handle cases of child abuse and neglect could also benefit from more research on the effects of parental medical marijuana use as various court cases have struggled with how to handle this situation (Huffington Post, 2011). To begin to address this research gap, we conducted focus groups of adult medical marijuana patients to understand how medical marijuana use may affect parenting.

METHOD

Participants

Study participants were 32 (14 females and 18 males) medical marijuana patients in the Denver, Colorado metropolitan area. Participants were recruited by flyers posted at medical marijuana centers and by word of mouth. Inclusion criteria were: 1) aged 18 years or older; 2) ability and willingness to provide written, informed consent in English; and 3) have a current Colorado Medical Marijuana Registry card. The exclusion criterion was: 1) insufficient English proficiency to participate in a focus group.

Measures

The authors developed a semi-structured focus group guide designed to understand how the medical marijuana system works for medical marijuana patients. Each focus group was conducted by a single facilitator while two assistants who took notes. Interviewers were all doctorate level researchers with extensive experience and training in qualitative interviewing methods. Focus groups were conducted separately by gender to encourage open communication about potentially sensitive subjects. Three focus groups were conducted for women and two for men. Focus groups were held in a private office to ensure the confidentiality of the information shared. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

In addition, research participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire developed for the study.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to strengthen the confidentiality of the research data. All research participants provided written informed consent prior to research participation. Data collection took place between May and July 2012. Participants were reimbursed $50 dollars for their time.

Analyses

Facilitators compared the transcriptions to session notes and corrected errors when applicable. The transcripts were then uploaded to Atlas-ti® qualitative data analysis software. Four members of the team (IB, KC, DR, CT) coded the focus group transcripts based on codes that were developed a priori and that emerged during the coding process. The coding team then met regularly to discuss the coding schemata. Differences in coding were resolved and, from these sessions, a final codebook was developed for the focus groups. For the current analysis, themes related to parenting and the impact of medical marijuana on children and adolescents are used. Data from the demographic questionnaire were used to describe the sample.

Results

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample. In general, there were slightly more males than females, and Caucasian was the most common racial group. Eleven (34.4%) participants alluded to being parents in the focus groups. Participants reported multiple reasons for using medical marijuana with the following being the most common: pain (n=19, 59.4%), mood stabilization/depression (n=10, 31.3%), anxiety (n=10, 31.3%), insomnia (n=8, 25.0%), post-traumatic stress disorder (n=8, 25.0%) and relaxation (n=8, 25.0%).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n=32)

| Age in years, mean, SD, range | 38.4, 17.0, 22–65 |

| Female, n (%) | 14 (43.75%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino n (%) | 4 (12.5%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African American | 6 (18.8%) |

| Native American | 1 (3.1%) |

| White | 19 (59.4%) |

| Other | 6 (18.8%) |

| Reasons for medical marijuana use, n (%)† | |

| Pain | 19 (59.4%) |

| Mood stabilization/depression | 10 (31.3%) |

| Anxiety | 10 (31.3%) |

| Post traumatic stress disorder | 8 (25.0%) |

| Insomnia | 8 (25.0%) |

| Relax | 8 (25.0%) |

| Appetite/nausea | 6 (18.8%) |

| To enhance sex | 4 (12.5%) |

| “Pre-menstrual syndrome”/cramps | 3 (9.4%) |

| Fun | 3 (9.4%) |

| Psychosis | 3 (9.4%) |

Note:

Subjects were allowed to give more than one reason for medical marijuana use.

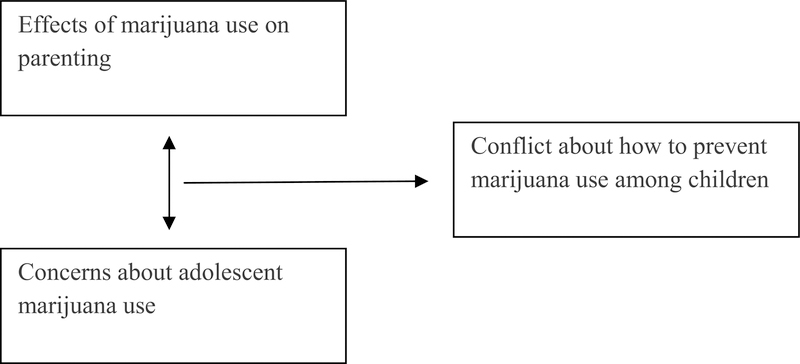

Some medical marijuana patients reported a dichotomy in their thinking: they believed that marijuana use helped them manage difficult emotions related to parenting, but they did not want their children to use marijuana. This tension led to the question of how to handle the issue of marijuana with their children. This conflict formed the conceptual model that summarizes the study findings (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Conceptual Model of How Medical Marijuana Patients Approach Marijuana as It Relates to Parenting.

How Marijuana Use Affects Parenting

Eleven participants identified themselves as parents in the focus groups. Thirteen focus group participants reported marijuana helped them relax and stay calm, and six participants reported that marijuana helped them stay calm around their children. It should be noted that no participants reported any violence toward children. This belief in the calming effects of marijuana is summarized in the following quote from a mother who reported a history of being in a relationship with a man who was violent towards her:

You know you are supposed to be taught as a parent not to holler, not to scream, not to hit your kid because that’s going to show them that they are allowed to do that when they get older. It’s easier to go and smoke and stay calm and let them do what they want and just kind of ignore it, and let it roll off. I am more patient, more calm with them.

This belief that marijuana helped to stay calm with children was echoed by another mother:

Both of my two oldest are ADHD and they conflict head to head constantly. So, smoking,…I’m able to sit down, think and put myself in their shoes and be able to talk to them more and have them understand what I’m doing and why. Rather than just yelling at them and hitting them.

Two female participants also expressed concern about how Child Protective Services might react to their marijuana use and felt that having a medical marijuana license gave them peace of mind from a legal perspective. The quote below is from a mother who reported she was going through a difficult custody battle with the father of her children.

Actually, right now I am facing a case with social services, because my baby’s dad tried to get custody of my kids and that was the first thing they brought up. They were like, ‘Are you smoking, do you have a medical marijuana card?’ Yeah, I have a medical marijuana card. I know I can’t smoke in front of my kids, but I don’t smoke. I eat it.

Belief That Children Should Not Be Using Marijuana

Despite the feeling that marijuana use helped parents manage difficult feelings toward their children, eight focus group participants reported that children should not use marijuana. This belief was summarized by the following quote from one mother:

I don’t want my son to go out and think that ‘just because mom’s doing it because she has a card and she’s legal it’s cool and I want to be like mom. I’m going to go smoke with my friends down the street.’ That’s what I’m saying I don’t want. I don’t want them to get into my stash. I have it locked with a key.

However, one male participant expressed the belief that teenagers are going to use substances anyway, and, if they are going to use something, marijuana is safer than alcohol or prescription drugs, especially opioids. This participant said, “Talk to your kids. I would much rather them be doing cannabis than Oxycontin.” The theme that marijuana use seems safer than other substance use, was also expressed by another male participant, who remarked, “I’d rather have my 16 year old smoking weed than drinking alcohol, doing heroin, doing coke and all that. Nothing really wrong with marijuana…as long as my son stays home doing it, no problem. I’d rather them do that than all that other stuff.”

How to Interact with Children and Adolescents About Marijuana

The feeling among some participants that marijuana helped them manage anger and other difficult emotions related to parenting existed alongside the general belief that teenagers should not use marijuana. The concern about preventing their children’s use led to the question of how medical marijuana patients should approach their children about marijuana. Six parents reported wondering about how to handle this difficulty. One mother asked the following question: “Do your kids smoke or do you hide it, or how do you deal with that? Because I have a baby and that’s what I try and figure out….”

Four parents felt that the best solution was to hide their marijuana use. One mother remarked: “Like my 7 year old, I feel really guilty at times because sometimes I do have to take a time out and go to my bedroom and I hit the vaporizer or whatever...you can’t really smell it when you do it with a vaporizer. But I’m really cautious.”

Two parents thought that being open with their children was the best solution: “My kids… they know what I do…. They know I’m having a ‘session.’ They won’t come and disturb me and they actually will make sure they’re dealing with their little sister if she happens to be up.”

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study, six of 11 medical marijuana patients who identified themselves as parents felt that marijuana helped them be calmer and more patient with their children. On the other hand, most of the parents in our sample did not want their children to use marijuana, even if they believed that marijuana was less harmful than other substances. These two conflicting values led to the dilemma of how to approach the subject of marijuana with their children. Some medical marijuana patients felt that hiding their marijuana use from their children was the best solution. Others felt that being open with their children about marijuana was the best option.

There are several limitations to our study. First, qualitative research provides depth, as opposed to breadth, in understanding a topic or issue (Giacomini and Cook, 2000a; Giacomini and Cook, 2000b). Therefore, these results may not generalize to other samples of medical marijuana patients, and our study population may not represent the broad range of parents across the wide spectrum of medical marijuana users. Second, we did not obtain a thorough parenting history from the participants (e.g. number of children, age of children, custody status of children, and so on). Therefore, it is possible that some of the focus group participants did not have children or did not currently live with children. Finally, we caution that this study design does not allow for any conclusions recommending that parents use marijuana to improve their parenting.

Nevertheless, we are unaware of other research examining the potential impact of medical marijuana use on parenting. Therefore, these data may provide important initial insights into future clinical and research directions with medical marijuana patients and their children.

First, there seems to be agreement among medical marijuana patients that marijuana has harmful effects for children and adolescents. This agreement represents potential common ground for caseworkers, clinicians and medical marijuana patients.

Second, some medical marijuana patients thought that marijuana helped them be calmer and more patient with their children. This perspective is important for clinicians and researchers to understand even if they disagree with this viewpoint. Understanding this perspective also informs potential interventions to reduce marijuana use or improve parenting among medical marijuana patients by enhancing stress management and emotional control techniques. Our results showing that medical marijuana patients sometimes used marijuana to help with psychiatric and emotional symptoms also underscore the importance of screening and evaluating potential medical marijuana patients for underlying psychiatric disorders that could be treated with proven interventions.

Finally, some research participants expressed concern about how to approach their children about marijuana. This concern represents more common ground in which patients and treatment providers can come together to problemsolve around how to interact with children about medical marijuana use. For example, the pros and cons of disclosing information can be discussed. If information about marijuana use is discussed with children, it can also be helpful to plan what kind of information to disclose, how to disclose it and when to disclose it. Our results also reflect the importance of discussing ways to safeguard medical marijuana so that children and adolescents cannot access it and discussing the availability of a sober adult to assist with emergencies that may arise.

Our findings also point toward future research directions. This study assessed possible benefits of marijuana use on parenting but research is also needed to assess how marijuana use may impair parenting. For example, this study did not elicit information about whether participants ever felt too relaxed to parent adequately or if marijuana use ever impaired their judgement around parenting. Research is also needed to understand why medical marijuana patients do not want their children to use marijuana to reinforce parents’ motivation to prevent their children from using the substance.

From the child’s perspective, research is needed to evaluate how knowing someone with a medical marijuana registration affects marijuana-related attitudes and behaviors. While medical marijuana diversion to adolescents is common, more information is needed about the exact source of diverted medical marijuana and if parents and family are a common source (Thurstone et al., 2011; Salomonsen-Sautel et al., 2012). This information would inform interventions to reduce medical marijuana diversion. Finally, interventions designed to educate parents about safeguarding medical marijuana and ensuring the availability of a sober adult to assist with emergencies that may arise, need to be developed and evaluated.

In summary, this study found the following common themes among medical marijuana patients:

some patients felt that marijuana helped them control difficult feelings related to parenting;

most patients did not want their children to use marijuana;

some patients were not clear about the best way to interact with their children about medical marijuana use.

The clinical implication of these findings is that many medical marijuana patients may be committed to preventing marijuana use among their children and may be open to ideas about how to do so. Future research is needed to identify and evaluate specific interventions to assist medical marijuana patients with preventing marijuana use among their children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grant 5R01 DA031816 (Principal Investigator, Dr. Booth).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

All of the authors are affiliated with the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Christian Thurstone, M.D. is a child psychiatrist, addiction psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. He also serves as the medical director of the Denver Health adolescent substance treatment program.

Ingrid A. Binswanger, M.D., M.P.H. is board-certified in internal medicine and is an associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Her research focuses on improving health among criminal justice populations and reducing the medical complications of drug use.

Karen F. Corsi, Sc.D., M.P.H. is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Her research focuses on HIV and HIV prevention among people with addiction.

Deborah J. Rinehart, Ph.D. is an assistant research scientist at Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

Robert E. Booth, Ph.D. is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. For over 25 years of experience, he has conducted research in the field of addiction and HIV prevention.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

REFERENCES

- Bowles D, W. (2012). Persons registered for medical marijuana in the United States. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15, 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, & Vandrey R (2004). Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1967–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado State Constitution (2001). Retrieved from http://www.colorado.gov/cs/Satellite?blobcol=urldata&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadername2=Content-Type&blobheadervalue1=inline%3B+filename%3D%22Colorado+Constitution+Article+XVIII.pdf%22&blobheadervalue2=application%2Fpdf&blobkey=id&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobwhere=1251807302173&ssbinary=true

- Conaboy C (2012, November 6). Massachusetts voters approve ballot measure to legalize medical marijuana. Boston Globe; Retrieved from <http://www.boston.com/metrodesk/2012/11/06/massachusetts-voters-approve-ballot-measure-legalize-medical-marijuana/EpDzgJGfBjnOAkoXpJwm1K/story.html> [Google Scholar]

- Curtis PA, & McCullogh C (1993). The impact of alcohol and other drugs on the child welfare system. Child Welfare, 6,533–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizikis C (2012, December 3). If medical marijuana bill passes, what can Illinois expect? Chicago Tribune; Retrieved from <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-12-03/news/ct-met-medical-marijuana-20121203_1_medical-marijuana-lou-lang-reform-of-marijuana-laws> [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ (2000a). User’s guide to the medical literature, XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, & Cook DJ (2000b). User’s guide to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, & Degenhardt L (2009). Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet, 17, 1383–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Griesler PC, Lee G, Davies M, & Schaffsan C (2001). Parental influences on adolescent marijuana use and the Baby Boom generation: Findings from the 1979–1996 National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher K, Chaffin M, Hollenberg J, & Fischer E (1994). Alcohol and drug disorders among physically abusive and neglectful parents in a community-based sample. American Journal of Public Health, 84,1586–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Jellinek M, Quinn D, Smith G, Poitrast FG, Goshko M (1991). Substance abuse and serious child mistreatment: Prevalence, risk, and outcome in a court sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 15,197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollin EJ (2011, September 26). Medical marijuana lights up child custody court. Huffington Post; Retrieved from <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/edra-j-pollin/medical-marijuana-lights-_b_974848.html> [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsen-Sautel S, Sakai JT, Thurstone C, Corley R, Hopfer C (2012), Medical marijuana use among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 694–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout D & Moore S (2009, October 19), U.S. won’t prosecute in states that allow medical marijuana. New York Times; Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/20/us/20cannabis.html?_r=0> [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone C (2010, January 31). Smoke and mirrors: Colorado teenagers and marijuana. Denver Post; Retrieved from <http://www.denver-post.com/opinion/ci_14289807> [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone C, Lieberman S, Schmiege SJ (2011), Medical marijuana diversion and associated problems in adolescent substance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 489–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census (2012), Profile of general demographic and housing characteristics: 2010 Retrieved from <http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkm>

- World Briefing:The Netherlands: Medical marijuana on sale (2003, September 2). New York Times; Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/02/world/world-briefing-europe-the-netherlands-medical-marijuana-on-sale.html%3Fref=marijuana> [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M (2012, September 7). Pot for Parents. New York Times; Retrieved from <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/08/opinion/how-pot-helps-parenting.html?_r=0> [Google Scholar]