Abstract

Objective

The aims of this feasibility study of an adapted lifestyle intervention for adults with lung cancer were to: 1) determine rates of enrollment, attrition and completion of five nurse-patient contacts, 2) examine demographic characteristics of those more likely to enroll into the program, 3) determine acceptability of the intervention, and 4) identify patient preferences for the format of supplemental educational intervention materials.

Methods

This study used a single arm, pre-and post-test design. Feasibility was defined as ≥ 20% enrollment and a completion rate of 70% for five nurse-patient contact sessions. Acceptability was defined as 80% of patients recommending the program to others. Data was collected through electronic data-bases and phone interviews. Descriptive statistics, Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test were used for analyses.

Results

Of 147 eligible patients, 42 (28.6%) enrolled and of these, 32 (76.2%) started the intervention and 27 (N=27/32; 84.4%; 95% CI: 67.2–94.7%) completed the intervention. Patients who were younger were more likely to enroll in the study (p = 0.04) whereas there were no significant differences by gender (p=0.35). Twenty-three of the 24 (95.8%) participants’ contacted post-test recommended the intervention for others. Nearly equal numbers of participants chose the website, (n=16, 50%) vs. print (n=14, 44%).

Conclusion

The intervention was feasible and acceptable in patients with lung cancer. Recruitment rates were higher and completion rates were similar as compared to previous home-based lifestyle interventions for patients with other types of cancer. Strategies to enhance recruitment of older adults are important for future research.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, lung cancer, lifestyle risk reduction intervention, nurse-delivered coaching intervention

Background

Adults with lung cancer are living longer due to improvements in early detection and cancer treatments.1–3 As the length of survival increases, it is important to identify interventions that will also improve health-related quality of life (HR-QOL). Despite the fact that adults with lung cancer often experience lower HR-QOL as compared to adults with other types of cancer, few interventions have targeted this vulnerable and growing population.4 A promising avenue to improve HR-QOL is to promote self-management of healthy lifestyle behavors already associated with improved HR-QOL among breast, prostate and colorectal cancer survivors.5,6 A healthy lifestyle is defined as 150 minutes of moderate exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise/week, eating at least 2.5 cups of fruits and vegetables/day, limited consumption of red meat, and smoking cessation.7

Smoking, physical activity, and diet are important lifestyle factors associated with improved HR-QOL, lung cancer risk, recurrence and survival.8–11 There is growing evidence of the importance that these lifestyle factors play in improving outcomes among all cancer survivors. Moreover, current lifestyle recommendations for cancer prevention and health promotion among cancer survivors focus on multiple lifestyle behaviors.7,12 Green and colleagues conducted a systematic review examining multiple lifestyle risk reduction interventions among cancer survivors and those at risk for cancer.13 The majority of studies were conducted in breast, prostate and colorectal cancer patients. Results from this review indicated that the majority of interventions that addressed multiple lifestyle risk reduction improved lifestyle risk behaviors for at least two behaviors.

To our knowledge, no previous lifestyle risk reduction intervention studies have focused on adults with lung cancer. Cooley and colleagues14 examined interest and preferences for a health promotion intervention among adults with lung cancer and found the majority were interested in health promotion and preferred a program that focused on multiple lifestyle risk behaviors (physical activity, diet and smoking), included educational materials and had an interactional component. Healthy Directions was identified as an intervention that could be adapted for this group of patients. Emmons and colleagues15,16 tested Healthy Directions as a cancer prevention lifestyle intervention in primary care and found it to be efficacious in changing lifestyle behaviors in a diverse group of patients. This intervention was selected because it had the same components of an intervention that lung cancer patients identified as preferable in our previous study. Adapting existing evidence-based interventions to be appropriate for other target populations has the potential to facilitate the efficient development of new evidence-based interventions.17 Tailoring of the intervention is important because it improves the fit of the intervention to the new target population and can enhance outcomes.18 Adapting interventions for a new target population often requires modifying key characteristics of the intervention related to the new population. However, preserving the core elements responsible for the efficacy of the intervention is a key consideration to maintain fidelity of the intervention as originally designed in order to maintain efficacy.18

Once the intervention is adapted, establishing the feasibility of implementing the intervention in the new proposed population is necessary before conducting a larger randomized clinical trial. Feasibility studies provide an objective assessment of whether a project can be completed with an emphasis on factors that affect future successful clinical trial conduct.19 Feasibility studies often focus on the processes that are key to the study and may be iterative in order to refine the processes that are needed to ensure success of a future study. For example, in a feasibility study one would evaluate whether the proposed inclusion criteria are too restrictive to allow adequate recruitment in the time frame.20 Determining the feasibility and acceptability of behavioral interventions in the context of patients with lung cancer is an essential first step in developing interventions since enrollment and completion rates are often low and attrition rates are high in this patient population.21,22

Thus, the purpose of this study was to adapt the Healthy Directions lifestyle intervention to fit the target group of adults with lung cancer and examine the feasibility and acceptability of this lifestyle intervention. We focused on establishing the feasibility of the study by examining the recruitment, enrollment, completion, and acceptability of the proposed intervention. Acceptability was defined as assessing participants’ reaction to the program as to whether it was judged to be suitable for behavioral change and achieve the goal of the program.23 The specific aims were to: 1) determine rates of enrollment, attrition and completion of five nurse-patient contacts; 2) examine demographic characteristics of those who were more likely to enroll into the program; 3) determine the acceptability of the program defined as whether patients would recommend the program to others to enhance healthy lifestyle behaviors; and 4) identify preferences for the format of the intervention educational materials (print vs. web-based).

Methods

Design and Participants

This study used a single arm, pre- and post-test design to establish the feasibility and acceptability of Healthy Directions and was approved by the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and University of Massachusetts-Boston Institutional Review Board (protocol number 12–150).

Eligible patients received surgical treatment within the previous six months for stages I-III non-small-cell lung cancer, could read English, and had physician approval for participation. Patients were excluded if comorbidities interfered with the ability to increase their physical activity.

A chart review of all patients from the surgical thoracic oncology clinic at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital was completed to identify eligible participants. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to enrollment in the study.

Intervention

Theoretical Framework

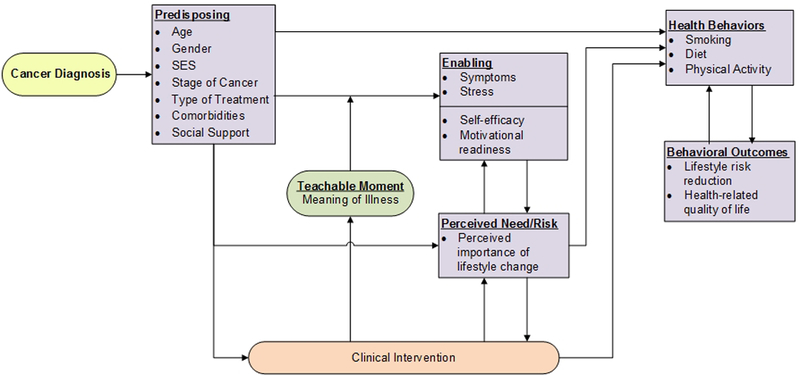

The “Health Behavior Model in Vulnerable Populations” and the “Teachable Moment” were the frameworks that guided this study (see Figure 1).24,25 The “Health Behavior Model for Vulnerable Populations”25 posits that certain predisposing characteristics such as age, gender socioeconomic status, and social support affect health outcomes and that an underlying mechanism may be that predisposing, enabling and perceived need components of the model directly influence personal health behaviors, which in turn affect HR-QOL and other clinical outcomes.25

Figure 1.

Theoreticla Framework: The Health Behavioral Model in Vulnerable Populations and the Teachable Moment

The “Teachable Moment” provides the framework for the enabling variables in the current study. The diagnosis and treatment for lung cancer provides an opportunity to leverage the teachable moment to enhance positive behavioral change. McBride and colleagues24 propose that a teachable moment, is a process of “sense-making” in which individual’s seek to interpret the significance, cause and “meaning” of the sentinel event. This event prompts one to experience an increase in perception of personal risk and vulnerability, creates strong affective responses and redefines one’s social role. This cognitive response precedes motivation, skills acquisition and self-efficacy, which affect the likelihood of behavioral change.26 Self-efficacy, defined as confidence in one’s ability to change health behaviors, has been associated with behavioral change among cancer survivors, including those with lung cancer.27–29 The presence of uncontrolled symptoms and affective responses such as, pain, fatigue, depression and anxiety have been associated with decreased self-efficacy in perceived ability to change health behaviors and decreased physical function.26,27,30

Adaptation of the “Healthy Directions” Lifestyle Intervention

A three-step process was used to adapt Healthy Directions for adults with lung cancer, which included 1) assessment, 2) preparation and adaption, and 3) implementation.17,18 During the assessment phase, we evaluated the needs of the target population and the goodness of fit of the proposed intervention. The Healthy Directions intervention was deemed appropriate for the target population based on results of a previous study that identified lung cancer patients preferred a multiple lifestyle risk reduction program and wanted the same components of an intervention that was available in Healthy Directions.14 The preparation phase entailed determining what changes needed to be made in order to adapt and tailor the intervention to the patient population. The theoretical framework, empirical literature, clinical experience of the principal investigator (MEC), guidance from the originator of the Healthy Directions intervention (KME), and feedback from the target group of lung cancer patients provided direction about changes that were needed to enhance and tailor the intervention. Minor modifications were made in the Healthy Directions intervention to better fit the target population and to ensure that we maintained the fidelity of the original intervention. Table 1 provides a comparison of the Healthy Directions-health centers and the Healthy Directions-lung cancer intervention components. As Table 1 indicates, the main modifications were related to addressing issues that were specific to adults with lung cancer such as adding disease specific information and having a RN deliver the intervention. A RN was deemed appropriate since the goal was to improve health behaviors among a group of patients that have multiple comorbidities and symptoms that wax and wane. Thus, an initial comprehensive assessment and ongoing monitoring was identified as a desirable component of the intervention. The feasibility study was initiated to evaluate the enrollment, attrition, and completion of the adapted Healthy Directions intervention in adults with lung cancer and identify characteristics of patients associated with enrollment into the study.

Table 1.

Comparison of the components of HD and adapted HD for lung cancer

| Intervention Component |

Healthy Directions | Healthy Directions-Lung Cancer |

Rationale for Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endorsement by clinician | In-person endorsement of study with prescription provided for behavior change later changed to baseline assessment with personalized report | Provided introductory letter from clinician and baseline assessment with personalized report | No change |

| Number of sessions and type of delivery | 1 in-person and 4 by telephone | 5 by phone | Patients were too sick at the clinical visit and the clinical schedule couldn’t accommodate additional activities |

| Tailored health education materials | Information about lung cancer, recovery after treatment, symptom management, breathing exercises, and stress reduction techniques | Additional modules developed to provide disease-specific information and that addressed common patient concerns | |

| Format for tailored educational materials | Print or web-based depending on patient preference | Print or web-based depending on patient preference | No change |

| Interventionist | Health advisor (Bachelor’s degree, experience in community settings and bilingual in English and Spanish) | Registered nurse (Bachelor’s degree, experience in providing health education) | Adults with lung cancer often have multiple symptoms and comorbidities. RN conducted health assessment to identify any physical limitations and communicate with MD. |

| Approach | Motivational interviewing | Motivational interviewing Wellness coaching | RN provided with training in health and wellness coaching |

Intervention Procedures

An eight-week lifestyle coaching intervention was implemented by a RN, which focused on enhancing physical activity, healthy diet, and smoking cessation. The intervention components and the way they were implemented during the feasiblity study are described in more detail. The first component was a welcome letter and a Healthy Direction toolkit which included a backpack containing a pedometer for tracking steps and educational materials. Once patients enrolled onto the study, they received the welcome letter, Healthy Directions toolkit and tailored educational materials with linkages to community resources by the research assistant. They were given a brief orientation to the materials depending on whether they choose print or web-based materials. The welcome letter provided a personalized endorsement of the study by the chairman of the thoracic surgery department (RB). After receiving the study materials patients completed an assessment, which included a self-administered baseline lifestyle questionnaire that was collected in the outpatient clinic or by phone depending on patient preference. The next step was creation of a personalized report: which was generated based on patient’s personal lifestyle behaviors and how these behaviors compared to the recommended guidelines. Patients were encouraged to track their progress toward reaching their goals over time. The RN used this personalized report to guide the coaching sessions and set goals with the participants. Five biweekly telephone calls were scheduled based on patient availability and a mutually convenient time. These coaching calls consisted of reviewing the patient’s lifestyle change goals and their current lifestyle behaviors. Principles of motivational interviewing and wellness coaching were used to guide the sessions. The nurse discussed appropriate material from the personalized reports, tracking reports and educational materials to identify any facilitators and/or barriers to behavior change and then collaborated with the patient to formulate specific, measureable and achievable goals. On follow-up calls, the nurse revisited the goals that were formulated on the previous call and discussed any successes or challenges that participants faced in reaching their goals from the last session. Weekly team meetings were held between the RN, research team and a physical activity consultant (SEC) if questions arose about ways to increase physical activity. Algorithms developed by Emmons and colleagues from the previous Healthy Directions intervention were used to guide increases in physical activity over time.16,31

Feasibility and Acceptability

Feasibility focused on determining enrollment, completion, and acceptability rates and success was defined a priori as ≥ 20% enrollment rate among those eligible for the study and a completion rate of 70% for the five nurse-patient contact sessions. This was based on rates from previous studies focused on patients with lung cancer.32 Acceptability was defined as 80% of patients recommending the program to others.

Measures

Patient characteristics were obtained from self-report and included age, gender, race, education level, comorbidities, and marital status. Comorbidities were measured by the Adapted Human Population Laboratory Comorbidity Questionnaire,33 which asked the patient whether they have ever been diagnosed with 20 different comorbid conditions. This questionnaire has been used extensively in epidemiological studies and in cancer patients.

Clinical variables were obtained from patient medical records. The variables of interest included stage of disease, histology, type of surgery, other cancer treatments received by patients and height and weight was obtained to calculate body mass index. The American Joint Committee for Cancer Staging guidelines was used to guide staging of disease.34

Enrollment rates were measured through a computerized data base that tracked the number of eligible patients who agreed to participate in the study, rates of attrition and reasons that participants refused to participate or dropped out of the study.

Completion of nurse-patient contacts were measured through a computerized data-base that tracked the number of contacts for the intervention and when the contact was initiated and completed.

Acceptability of the intervention was assessed by a structured question conducted by phone interviews at the conclusion of the study asking whether patients would recommend the intervention to others to enhance behavioral change. This question has been used in previous intervention studies.15

Data Analyses

Enrollment and attrition rates were reported as point estimates with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI). Summary statistics were used to evaluate other variables. Categorical and continuous variables were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results

Sample

Table 1 provides characteristics for those enrolling and starting the intervention. Most participants enrolled had early stage disease, were treated with a lobectomy, and had three or more comorbidities. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular and chronic respiratory disease.

Enrollment, Attrition and Completion Rates

Of the 147 eligible patients, 42 (28.6%) consented, 72 (49.0%) declined, and 33 (22.4%) could not be contacted (Figure 2). The exact binomial 95% CI of the enrollment rate for patients we attempted to contact was 21.4–36.6%. Of the 42 patients consenting to participate, the overall attrition was 38.1% (95% CI: 23.6–54.4%). Of the 42 patients enrolled, 32 (76.2%) started the intervention and 27 (84.4%; 95% CI: 67.2–94.7%) completed the intervention. Most attrition occurred before initiation of the coaching calls (N=10/15, 66.6%) and the main reasons were death or severity of illness (see Figure 2). Among those who started the intervention, the median time from date of surgery to the first coaching call was 11.8 weeks.

Figure 2.

Healthy Directions Lung Cancer Study Eligiblity, Recruitment, Enrollment and Retention Flow Diagram

Differences in Enrollment by Age and Gender

Of the patients who could be contacted (n=114), the median age for those enrolling was 63 years as compared to 69 years for those not enrolling (p=0.04). Of the 87 females and 59 males screened, there was no significant differences between the proportion of females (28/87; 32.2%) and males (14/59; 23.7%) enrolled in the study (p=0.35).

Acceptability of Lifestyle Intervention

Twenty-four of the 27 (88.9%) who completed the intervention were interviewed. Twenty-three of the 24 (95.8%) interviewed recommended the intervention to enhance behavioral change for others.

Preference for Study Materials

Of the 32 patients who started the intervention, 16 (50%) chose the website, 14 (44%) print, and 2 (6%) selected both formats.

Discussion

Our enrollment rate of 28.6% (N=42/147) was higher than the 5.7% rate reported for three of the largest home-based lifestyle interventions for patients with other types of cancer.35 One of the potential reasons that our enrollment rate may have been higher as compared to other studies is that all of the patients recruited for this study were recently diagnosed. There is emerging evidence that the time surrounding the diagnosis of cancer may provide an opportunity to positively impact patient’s health behaviors through the “teachable moment”.24 Patients that are closer to the time of the diagnosis may be more interested and willing to change their health behaviors. Adams and colleagues examined predictors of enrollment into a lifestyle intervention and found that among participants in the RENEW study there was a 7% decrease in the likelihood of enrolling into the study for every additional year from the time of diagnosis.35

The completion rate for participants who started the intervention was 84.4% (N=27/32) which is similar to the completion rate (91.1%) for other lifestyle interventions for patients with other types of cancer.35 The majority of participants in our study found the intervention highly acceptable. Given that all of our a priori criteria regarding enrollment, completion rates and acceptability were met, this study provided evidence for the feasibility of this multiple lifestyle intervention in patients with NSCLC.

Some of the findings offer direction for enhancing recruitment and retention of patients with lung cancer in future studies. First, attrition before starting the intervention was high among this sample. As in other lung cancer studies, the most common reasons for attrition were death and severity of illness.36 Other factors were feeling overwhelmed around the time of diagnosis and needing adequate time to recover from surgery. Patients who started the intervention had surgery a median of approximately 3 months prior to the first coaching call, suggesting this may be the optimal time to initiate this intervention rather than any closer to receipt of surgery or the diagnosis. Evidence suggests that the window of time to capitalize on the teachable moment after a major life-threatening illness may occur up to approximately two to three years after the diagnosis but further research is needed to more clearly understand the intersection between the time of diagnosis and delivery of interventions.24 Second, younger patients were more likely to enroll in the study, which is similar to the study by Adams and colleagues that found that for every one year increase in age there was a 5% decrease in likelihood of enrolling into their lifestyle intervention study.35 Recruitment of older adults with cancer can be challenging due to high medical acuity.37 Future studies need to implement recruitment strategies that specifically address common barriers to engaging older adults in research. It may also be important to develop lifestyle programs that are tailored to the specific needs of older adults with lung cancer to increase uptake.

Another consideration is that most participants in this study had at least three comorbidities, which included cardiovascular disease and chronic respiratory disease. Integration of lifestyle interventions into the care of those with multiple comorbidities has the potential to greatly enhance clinical care. In a study by Wang and colleagues,8 the influence of comorbid disease and physical activity on HR-QOL was evaluated among 701 adults with lung cancer and the results suggested that physical activity had a positive association with HR-QOL even among those with multiple comorbidities.

Only half of the participants in this study chose the web-based format for the intervention materials. Participant choice for the type of materials (web or print materials) they preferred to use was comparable between our study and the Healthy Directions 2 study. Greaney and colleagues38 found that those who were more likely to choose the web-based format in Healthy Directions 2 were younger, reported better financial situation, had greater computer comfort and more frequent Internet use. Hong and Cho39 recently examined trends of health-related Internet use among older adults and found that the digital health divide has narrowed between different demographic groups such as gender, race and ethnicity, however, those who were 75 years and older and those with lower education lagged behind others in all aspects of health-related Internet use. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of having intervention materials available in both formats to reach diverse groups of patients. It may be especially important to have senior friendly materials for vulnerable older adults with lung cancer.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this feasibility study was that it was conducted within one center and that there was a lack of racial and ethnic diversity within the sample. Accrual of ethnically diverse patients in behavioral research from comprehensive cancer centers tends to be difficult,40 especially those with early stage lung cancer as black patients tend to be diagnosed at later stages. However, the original Healthy Directions study was conducted in community-based centers and recruited a diverse sample of patients. We used the same materials that were developed, tested, and found to be efficacious among this diverse group of patients. Future studies that examine efficacy should focus on enhancing outreach and recruitment of a more diverse sample at multiple sites.

Clinical Implications

Patients with lung cancer tend to have multiple comorbidities and symptoms that change over the course of time. To date, few interventions have been conducted within this vulnerable group of patients. Lifestyle interventions after the diagnosis of lung cancer have the potential to improve clinical outcomes. The Healthy Directions intervention was the first multiple lifestyle risk reduction intervention adapted and tailored to fit the needs of patients with lung cancer. Results from this study suggest that this intervention was feasible and highly acceptable. It appears that the optimal time to initiate the intervention is at least three months after surgery. This time period allows for patients to adjust to the diagnosis and recover from their surgery so they are ready to focus on behavioral change. Understanding who participates in behavioral clinical trials is important to develop interventions with a broader reach. Younger patients were more likely to enroll into this study as compared with older adults. Further attention is needed to increase participation and uptake of lifestyle interventions that have the potential to improve HR-QOL and functional outcomes among older adults with lung cancer.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients enrolling and starting the intervention

| Overall | Started Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| N | 42 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 32 | 100 |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 14 | 33.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 11 | 34.4 |

| Female | 28 | 66.7 | 7 | 70.0 | 21 | 65.6 |

| Age, median (range) | 63 (40–81) | 70 (48–81) | 62 (40–76) | |||

| Education | ||||||

| Missing | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ≤HS | 12 | 28.6 | 5 | 50.0 | 7 | 21.9 |

| >HS | 29 | 69.0 | 4 | 40.0 | 25 | 78.1 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 13 | 31.0 | 4 | 40.0 | 9 | 28.1 |

| Married/Partnered | 29 | 69.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 23 | 71.9 |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 20 | 47.6 | 6 | 60.0 | 14 | 43.8 |

| II | 6 | 14.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 5 | 15.6 |

| III | 14 | 33.4 | 2 | 20.0 | 12 | 37.6 |

| Missing | 2 | 4.8 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 3.1 |

| Surgery Type | ||||||

| Pneumonectomy | 4 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12.5 |

| Lobectomy | 23 | 54.8 | 5 | 50.0 | 18 | 56.3 |

| Wedge/section Resection | 14 | 33.4 | 5 | 50.0 | 9 | 28.1 |

| Other | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.1 |

| Number of co-morbidities | ||||||

| 0 | 4 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 12.5 |

| 1 | 6 | 14.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 5 | 15.6 |

| 2 | 8 | 19.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 6 | 18.8 |

| ≥3 | 24 | 57.1 | 7 | 70.0 | 17 | 53.1 |

Acknowledgments

Funding: Lung Cancer Research Foundation (MEC), the Phyllis F. Cantor Center, Research in Nursing and Patient Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science (1UL1RR031982–01 U54, ACB)

References

- 1.Heon S, Johnson BE. Adjuvant chemotherapy for surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(3):S39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Lung Screening Trial Research T, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhai H, Zhong W, Yang X, Wu YL. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) therapy for lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4(1):82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal A, Lewison G, Idir S, et al. The State of Lung Cancer Research: A Global Analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(7):1040–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosher CE, Sloane R, Morey MC, et al. Associations between lifestyle factors and quality of life among older long-term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(17):4001–4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin ML, Cartmel B, Harrigan M, et al. Effect of the LIVESTRONG at the YMCA exercise program on physical activity, fitness, quality of life, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JW, Gong XH, Ding N, et al. The influence of comorbid chronic diseases and physical activity on quality of life in lung cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(5):1383–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam TK, Gallicchio L, Lindsley K, et al. Cruciferous vegetable consumption and lung cancer risk: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson GE, Tucker MA, Venzon DJ, et al. Smoking cessation after successful treatment of small-cell lung cancer is associated with fewer smoking-related second primary cancers. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green AC, Hayman LL, Cooley ME. Multiple health behavior change in adults with or at risk for cancer: a systematic review. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(3):380–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooley ME, Finn KT, Wang Q, et al. Health behaviors, readiness to change, and interest in health promotion programs among smokers with lung cancer and their family members: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(2):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emmons KM, Stoddard AM, Gutheil C, Suarez EG, Lobb R, Fletcher R. Cancer prevention for working class, multi-ethnic populations through health centers: the healthy directions study. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(8):727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emmons KM, Stoddard AM, Fletcher R, et al. Cancer prevention among working class, multiethnic adults: results of the healthy directions-health centers study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1200–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Card JJ, Solomon J, Cunningham SD. How to adapt effective programs for use in new contexts. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, et al. Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran WJ Jr., Schiller JH, Wolkin AC, Comis RL, Scientific Leadership Council in Lung Cancer of the Coalition of Cancer Cooperative G. Addressing the current challenges of non-small-cell lung cancer clinical trial accrual. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9(4):222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn L, Keedy VL, Campbell N, et al. Identifying barriers associated with enrollment of patients with lung cancer into clinical trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):156–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coups EJ, Park BJ, Feinstein MB, et al. Correlates of physical activity among lung cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18(4):395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins HY, Baum GP, Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist KM. Effects of treatment factors, comorbidities and health-related quality of life on self-efficacy for physical activity in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18(4):405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooley ME, Wang Q, Johnson BE, et al. Factors associated with smoking abstinence among smokers and recent-quitters with lung and head and neck cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin D, et al. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2(3):261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung R, Krebs P, Coups EJ, et al. Fatigue and functional impairment in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(2):426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Greaney ML, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of Healthy Directions 2--a multiple risk behavior intervention for primary care. Prev Med. 2014;64:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du W, Gadgeel SM, Simon MS. Predictors of enrollment in lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;106(2):420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satariano WA, Ragland DR. The effect of comorbidity on 3-year survival of women with primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(2):104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th Ed. ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams RN, Mosher CE, Blair CK, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Demark-Wahnefried W. Cancer survivors’ uptake and adherence in diet and exercise intervention trials: an integrative data analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(1):77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooley ME, Sarna L, Brown JK, et al. Challenges of recruitment and retention in multisite clinical research. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(5):376–384; quiz 385–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greaney ML, Puleo E, Bennett GG, et al. Factors associated with choice of web or print intervention materials in the healthy directions 2 study. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1):52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong YA, Cho J. Has the Digital Health Divide Widened? Trends of Health-Related Internet Use Among Older Adults From 2003 to 2011. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mock V, Hill MN, Dienemann JA, Grimm PM, Shivnan JC. Challenges to behavioral research in oncology. Cancer Pract. 1996;4(5):267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]