Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Identify substance and psychiatric predictors of overdose (OD) in young people with substance use disorders (SUD) who received treatment.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective review of consecutive medical records of young people who were evaluated in a SUD program between 2012 and 2013 and received treatment. An independent group of patients from the same program who received treatment and had a fatal OD were also included in the sample. OD was defined as substance use associated with a significant impairment in level of consciousness without intention of self-harm, or an ingestion of a substance that was reported as a suicide attempt. T-tests, Pearson’s chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests were performed to identify predictors of OD after receiving treatment.

Results:

After initial evaluation, 127 out of 200 patients followed up for treatment and were included in the sample. Ten (8%) of these patients had a non-fatal OD. Nine patients who received treatment and had a fatal OD were also identified. The sample’s mean age was 20.2 ± 2.8 years. Compared to those without OD, those with OD were more likely to have a history of intravenous drug use (OR: 36.5, p<0.001) and mood disorder NOS (OR: 4.51, p=0.01).

Discussion and Conclusions:

Intravenous drug use and mood dysregulation increased risk for OD in young people who received SUD treatment.

Scientific Significance:

It is important to identify clinically relevant risk factors for OD specific to young people in SUD treatment due to the risk for death associated with OD.

Keywords: substance use disorder, overdose, young people, psychiatric, treatment

I. Introduction

There has been a substantial increase in overdoses (OD) over the past fifteen years.1–3 In 2017 70,237 individuals died of an OD in the United States.4 Individuals with a substance use disorder (SUD) are particularly vulnerable to OD with a recent meta-analysis reporting that individuals with SUD were five times more likely to have a fatal OD compared to those without SUD.5 Although the rate of OD has been highest among middle age adults, adolescents and young adults have likewise been affected5 and between 1999 and 2015 the rate of OD deaths in adolescents 15 to 19 years of age doubled.6

Although OD is one of the leading causes of death in young people,7 ages 16 to 26 years,8 relatively little research exists on risk factors associated with OD in this age group. The existing literature has primarily focused on OD risk factors in homogeneous populations of young people in the community such as individuals with opioid use,9,10 tranquilizer use,10 heroin use,11,12 intravenous drug use,13–15 and homeless youth.16–18 Risk factors for OD in young people that have been replicated include substance specific factors such as use of: heroin14,16,18, methamphetamine,16,18 tranquilizers,10,12 and cocaine.13,18 History of intravenous drug use9,10,12,16,17,19 and history of witnessing an individual OD10,13 are also replicated risk factors in young people. We recently examined OD risk factors reported retrospectively in a more heterogeneous sample of young people with SUD at initial evaluation for SUD treatment.19 We found that in addition to characteristics associated with more severe SUD, psychopathology in general, and mood disorders in particular, were associated with a history of non-fatal OD.

These largely community-based studies have been helpful to identify important OD risk factors in young people for public health officials to consider. Nonetheless, risk factors identified in community-based studies may not generalize to young people receiving SUD treatment, and it is important to identify risk factors in this population that clinicians can monitor and target with treatment. Our initial findings on risk factors associated with a history of OD in young people who present for SUD evaluation are useful for clinicians, but may not generalize to those who engage in treatment since many young people who present for treatment do not engage and subsequently receive treatment.20 It is therefore important to identify predictors for OD among young people who engage and receive SUD treatment that clinicians can be mindful of and monitor over time.

To this end, we now aim to examine the prevalence of OD among young people with SUD who received evidence-based outpatient treatment, and to identify clinically relevant substance and psychiatric characteristics from baseline evaluation and during treatment that predict future OD. Secondarily, we examined differences in the characteristics and correlates between non-fatal and fatal OD in this clinical sample. Based on the literature, we hypothesized that young people with a history of a prior OD, suicide attempt, and/or characteristics associated with more severe SUD such as intravenous drug use, would be more likely to OD compared to individuals without those respective substance use and psychiatric characteristics.

2. Methods

We conducted a systematic retrospective medical chart review of consecutive intake assessments between January 2012 and June 2013, completed in an outpatient SUD treatment program in a major northeast metropolitan medical center for young people 26 years of age or younger. Young people ages 16 to 26 years of age8 at intake assessment who had a diagnosis of SUD (substance abuse or dependence, DSM-IV-TR criteria) were included in the original sample. Detailed study methodology has been previously described.19

In our initial report, we focused on prevalence and factors associated with OD prior to the comprehensive intake assessment and initiation of SUD treatment. For the current analyses, we only included patients from the original sample who subsequently engaged in, and received treatment in the program. As articulated by Garnick and colleagues, engagement in care was defined as attending at least two follow-up appointments for any outpatient service within the program within thirty days of the initial evaluation.21 The program offered evidence based behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for SUD and psychiatric disorders.22 To examine for differences between non-fatal and fatal OD, we enhanced our sample by including known consecutive fatal OD between November 2013 and August 2016 among patients evaluated by the program who subsequently received treatment, and who were not part of the original sample. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, which approved the study as providing adequate protection for human subjects.

Information from the baseline evaluation and follow-up appointments were used to evaluate predictors of OD among young people with SUD who received treatment. Data extracted from patients’ clinical records at baseline evaluation included demographics, OD history, characteristics of their substance use including self-report of addiction severity (the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ)23), lifetime SUD diagnoses, SUD treatment history, lifetime diagnoses of psychiatric disorders, and psychiatric treatment history. After baseline evaluation for a period of up to 2.5 years, each note in the electronic health record that was linked to care in the program or the emergency room was carefully reviewed by study staff in sequential order. Data extracted during treatment included the number of appointments attended, type of engagement in treatment (continuous or intermittent), the presence or absence of medication treatment for SUD (acamprosate, buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, n-acetyl cysteine, naltrexone, or topiramate), and treatment in a higher level of care (partial hospital program, residential or inpatient SUD hospitalization, or psychiatric hospitalization).

Continuous engagement in treatment was defined as attending two treatment visits within a 30-day period for three consecutive months following baseline evaluation in the program. A patient was defined as being “in treatment” at the time of OD if they attended an appointment within the month prior to OD. Consistent with prior work,19,24–26 unintentional OD was defined as patient report of substance use without intention of self-harm that was associated with significant impairment in level of consciousness. Intentional OD was defined as patient report of an ingestion of any substance with the deliberate intention of self-harm19,27 that was reported as a suicide attempt. A death was classified as a presumed OD based on collateral from family or medical record regarding the circumstances surrounding the death and the patient’s substance use history.

2.1. Statistical Analyses

Comparisons were made first between patients with no OD and OD during follow-up. Subsequently, comparisons were made between patients with non-fatal and fatal OD during follow-up. In the event of missing data, subjects were excluded only from those analyses of predictors for which they were missing. For the treatment in a higher level of care variable we excluded patients who went to a higher level of care after an OD since the analysis was designed to identify variables that predicted OD. We analyzed continuous predictors using Student’s independent t-tests for parametric data and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for nonparametric data. Binary predictors were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests if any cell had an expected value less than five. In the event of zero cells, we added 0.5 to all cells to calculate the odds ratio. We also performed stepwise logistic regression (backwards selection, p≥0.05 for removal) starting with models that included all significant predictors from the bivariate analyses to identify the most significant predictors of OD during follow-up. To establish the unique predictive contribution to OD risk during follow-up, the most significant predictors of OD were entered into a simultaneous regression to estimate the relative contribution to OD risk while controlling for other variables. The estimated variance was calculated with a Nagelkerke pseudo-R.2 All tests were two-tailed and performed at the 0.05 alpha level using Stata® (Version 14). All data are presented as percentages, absolute numbers, or mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise described.

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

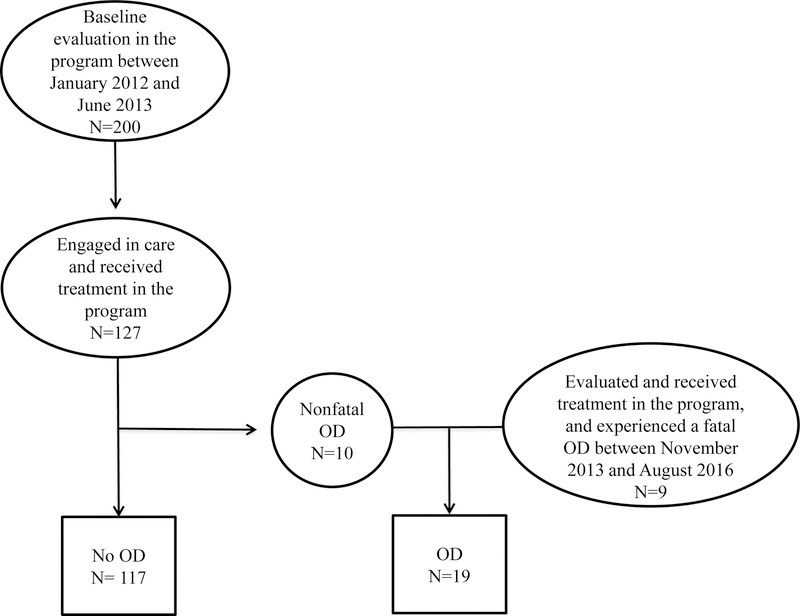

Among the 200 patients who were included in the original sample,19 127 patients (64%) engaged in care and received treatment after their baseline evaluation and were thus included in the current analyses. The 73 patients who did not continue in treatment in our program after their baseline evaluation were not included in the current analysis since they did not follow-up with the program and did not receive treatment. Patients who engaged in care when compared to those who did not engage in care were less likely to have a lifetime history of bipolar disorder (OR 0.35; CI: 0.14, 0.87, p=0.02) and more likely to have a lifetime history of a depressive disorder (OR 2.01; CI: 1.10, 3.66, p=0.02). No other differences were found between patients who did or did not engage in care in all other variables originally examined including lifetime SUD, characteristics associated with SUD, psychiatric disorder, and characteristics associated with psychiatric disorders (all p≥0.05). Nine patients who were evaluated by the program and received treatment, but were not part of the original sample, had a fatal OD and were included in the analyses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study sample

The full data set was available for 103 out of 136 patients. Among the patients with missing information, 56% (n=19) were only missing one data point.

3.2. OD Prevalence

The prevalence of OD among the 127 patients who engaged in care and received treatment was 8% (n=10). These overdoses were all non-fatal, the majority were unintentional (90%, n=9), and the majority involved opioids (70%, n=7).

Most of the non-fatal OD occurred within the first year after the patient’s initial evaluation in the program (n=9, 90%). Half of the non-fatal OD occurred while a patient was in treatment (n=5, 50%). Most patients continued in treatment and/or returned to treatment after a non-fatal OD (n=8, 80%).

Most of the fatal OD also occurred within the first year after the patient’s initial evaluation in the program (n=8, 80%). Half of the fatal OD occurred while a patient was in treatment (n=5, 50%).

3.3. Sample Demographics

We examined demographic differences between patients without an OD and those with non-fatal and fatal OD after receiving treatment (Table 1). Compared to patients without an OD those with non-fatal OD were older at initial evaluation (p=0.04). There was no significant difference in age at initial evaluation between patients without an OD and those with fatal OD (p>0.05). There were no significant differences between groups in sex or race. There were no demographic differences between the non-fatal and fatal OD groups (all p≥0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of patients who received treatment with no overdose (OD), non-fatal OD, and fatal OD

| No Overdose (OD) n=117 | Non-fatal OD n=10 | Fatal OD n=9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Initial Evaluation, mean ± SD, years | 20.0 ± 2.8 | 21.9 ± 2.0* | 20.7 ± 3.0 |

| Male Gender, n (%) | 92 (78.6%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (78%) |

| Caucasian, n (%)a | 104/115 (90.4%) | 9 (90%) | 8 (89%) |

p<0.05 when compared to patients during follow-up with no OD

full data set not available for race

3.4. SUD and Psychiatric Characteristics Associated with OD

We examined if there were specific SUD and psychiatric characteristics that predicted OD among young people who received treatment. We first evaluated for differences at baseline evaluation between those individuals who received treatment and subsequently had an OD compared to those who did not OD. Those with OD had a more severe SUD when they initially presented for treatment as measured by the LDQ compared to those without OD (12.8 ± 9.6 vs. 8.4 ± 6.8; t135=−2.44; p=0.02).

At entry into treatment, those who overdosed after receiving treatment versus those who did not OD were more likely to have a lifetime history of: an opioid UD, intravenous drug use, and inpatient detoxification at baseline (Table 2, all p<0.05). Furthermore, those who overdosed after receiving treatment were more likely at baseline to have a lifetime history of: mood disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) and self-injurious behavior compared to those who did not OD (Table 2, both p≤0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics at entry into treatment associated with later overdose (OD)

| Variable | No OD (n=117) | OD (n=19) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD Diagnosis | ||||

| Alcohol | 77 (65.8%) | 9 (47.4%) | 0.47 (0.18, 1.24) | 0.12 |

| Cannabis | 87 (74.4%) | 11 (57.9%) | 0.47 (0.17, 1.29) | 0.14 |

| Opioid | 37 (31.6%) | 15 (79.0%) | 8.11 (2.52, 26.12) | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 16 (13.7%) | 6 (31.6%) | 2.88 (0.78, 9.69) | 0.09 |

| Benzodiazepine | 11 (9.4%) | 5 (26.3%) | 3.40 (0.81, 12.73) | 0.05 |

| Amphetamine | 18 (15.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 1.99 (0.32, 8.94) | 0.51 |

| SUD Characteristics | ||||

| Abstinencea, b | 40/107 (37.4%) | 9/18 (50.0%) | 1.68 (0.61, 4.57) | 0.31 |

| Intravenous drug use | 11 (9.4%) | 15 (79.0%) | 34.28 (9.01, 167.65) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient detoxification | 24 (20.5%) | 9 (47.4%) | 3.44 (1.11, 10.68) | 0.02 |

| Medication for SUD | 16 (13.7%) | 6 (31.6%) | 2.88 (0.78, 9.69) | 0.09 |

| Blackouts b | 78/112 (69.6%) | 13/18 (72.2%) | 1.13 (0.37, 3.43) | 0.83 |

| Prior OD | 39 (33.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | 1.80 (0.68, 4.79) | 0.24 |

| Family history of SUD b | 45/103 (43.7%) | 6/17 (35.3%) | 0.70 (0.24, 2.05) | 0.52 |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis | ||||

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity | 68 (58.1%) | 11 (57.9%) | 0.99 (0.37, 2.65) | 0.99 |

| Anxiety | 65 (55.6%) | 12 (63.2%) | 1.37 (0.50, 3.73) | 0.54 |

| Depressive | 58 (49.6%) | 9 (47.4%) | 0.92 (0.35, 2.42) | 0.86 |

| Bipolar | 8 (6.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.76 (0.02, 6.26) | 1.00 |

| Mood (not otherwise specified) | 10 (8.5%) | 6 (31.6%) | 4.85 (1.24, 17.90) | 0.01 |

| Psychosis | 5 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.52 (0.03, 9.87) | 1.00 |

| Eating | 9 (7.7%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1.41 (0.14, 7.69) | 0.65 |

| Psychiatric Characteristics | ||||

| Self-Injurious Behavior | 31 (26.5%) | 11 (57.9%) | 3.81 (1.40, 10.36) | 0.006 |

| Suicide Attempt b | 20/116 (17.2%) | 5 (26.3%) | 1.71 (0.43, 5.79) | 0.35 |

| Psychiatric Hospitalization | 38 (32.5%) | 5 (26.3%) | 0.74 (0.25, 2.21) | 0.59 |

| Abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual) b | 31/114 (27.2%) | 7 (36.8%) | 1.56 (0.56, 4.33) | 0.39 |

| Family history of psychiatric disorder b | 61/104 (58.7%) | 10/18 (55.6%) | 0.88 (0.32, 2.42) | 0.81 |

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) depicting the bivariate associations of substance use disorder (SUD) and psychiatric characteristics at initial evaluation (lifetime history of) between patients who received care and overdosed and those with no OD.

Abstinence was defined as 90 days with no non-nicotine substance use.

Full data set not available for: abstinence, blackouts, family history of SUD, suicide attempt, abuse, and family history of psychiatric disorder.

We then examined clinical characteristics during treatment between those who overdosed after receiving treatment and those who did not OD (Table 3). Those who overdosed were more likely during treatment to take medication for their SUD and need treatment in a higher level of care compared to those with who did not OD (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics during treatment associated with later overdose (OD)

| Variable | No OD (n=117) | OD (n=19) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous engagement in care | 37 (31.6%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0.58 (0.18, 1.86) | 0.35 |

| Number of appointments attended, median [IQRa] | 14 [6, 36] | 10 [6, 49] | N/A | 0.42 |

| Higher level of care for SUD | 24 (20.5%) | 8/16b (50.0%) | 3.83 (1.13, 13.08) | 0.03 |

| Medication for SUD | 29 (24.8%) | 13 (68.4%) | 6.57 (2.29, 18.87) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric Hospitalization | 4 (3.4%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3.28 (0.28, 25.00) | 0.20 |

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) depicting the bivariate associations of substance use disorder (SUD) and psychiatric characteristics during follow-up between patients who overdosed and those who did not OD during follow-up.

Interquartile range

Three subjects went to a higher level of care after a non-fatal OD and were therefore not included in this analysis.

All substance use and psychiatric characteristics that were significantly (p<0.05) associated with OD in the bivariate analyses (Table 2 & Table 3) were entered into a stepwise logistic regression model to identify the most significant predictors for OD after receiving treatment. The model started with the following predictors: history of opioid UD, mood disorder NOS, self-injurious behavior, intravenous drug use, and inpatient detoxification at entry into treatment, as well as medication for SUD and treatment in a higher level of care during treatment. After removing insignificant predictors one by one based on the largest p-value ≥0.05, we arrived at a final model that identified history of intravenous drug use (OR=54.95; CI: 10.93, 276.34, p<0.001) and mood disorder NOS (OR=9.22, CI: 1.36, 62.57, p=0.02) as the most significant predictors of OD after receiving treatment. Using the Nagelkerke pseudo-R estimate, the amount of variance in risk for OD explained by each predictor was 46.2% for history of intravenous drug use at baseline evaluation and 8.4% for history of mood disorder NOS at baseline evaluation.

3.5. OD risk relative to number of SUD diagnoses

We also evaluated the risk for OD relative to the number of SUD diagnoses. There was no difference in OD risk after receiving treatment among patients with 2 or more SUDs and 1 SUD (all p≥0.05).

3.6. Non-fatal versus fatal OD

Examining only those patients with OD we tested for differences in SUD and psychiatric characteristics associated with non-fatal versus fatal OD. No differences in any SUD and/or psychiatric characteristics were found between the non-fatal and fatal OD groups (all p≥0.05).

4. Discussion

In a systematic review of young people with SUD who received evidence-based outpatient treatment we found 8% of young people ages 16 to 26 years who engaged in care and received treatment had a non-fatal OD in a two-and-a-half-year period. The majority of the overdoses (non-fatal and fatal) occurred within the first year after baseline evaluation. Our data generally supports our hypothesis that characteristics associated with more severe SUD and mood dysregulation predict OD after receiving treatment; however, we did not find that a history of a prior OD or suicide attempt at entry into treatment predicted OD after receiving treatment.

The prevalence of OD among young people who engaged in treatment in our sample (8%) was less than the prevalence reported by Mitra and colleagues (15.9%) in a prospective cohort study of homeless young people.16 It is not surprising that Mitra and colleagues reported a higher prevalence of OD as the subjects were a higher risk group of individuals who had the added burden of being recently homeless and using non-cannabis illicit drugs at baseline.16 It is also possible that the OD prevalence in our sample was lower since individuals with higher risk for OD may not have engaged in treatment; or conversely, treatment mitigated the risk for OD.

We also found that most of the non-fatal and fatal OD occurred within the first year of treatment suggesting that this is a time when young people are particularly vulnerable to OD. Interestingly, in our previous analysis of risk factors associated with history of OD at initial evaluation we found young people were presenting to our treatment program approximately within a year of their first unintentional OD.19 It may be that an OD motivates young people to seek SUD treatment. To our knowledge there are no studies to date that systematically evaluated for periods of OD risk before and after engagement in treatment in young people with SUD. Our findings seem to suggest that the first year before and after treatment engagement may be a time when young people are particularly vulnerable to OD. More research is needed to clarify the timing of OD in young people relative to substance use initiation and treatment engagement.

In general, we found that young people who had an OD after receiving treatment were more likely to have an opioid UD and characteristics associated with a more severe SUD. A history of intravenous drug use was a particularly robust risk factor that predicted OD. Our findings are consistent with the existing literature that has identified intravenous drug use9,10,13,15–17,19 and opioid use10,13,15,16 as risk factors associated with OD in previous studies of young people. Since research has demonstrated medication for opioid UD decreases OD risk,28 and opioid use/disorder is a risk factor for OD in young people, increased research is needed to identify and address barriers to the underutilization of medication for opioid UD in young people.29,30

Consistent with the existing literature, we found that self injurious behavior and/or a lifetime history of a mood disorder—both associated with mood dysregulation—predicted OD after receiving treatment. Similarly, an association was found between self-injurious behavior and history of OD in young people presenting for initial evaluation for SUD treatment.19 Our findings are also synonymous with Richer and colleagues (2013) who showed that suicidal thoughts were twice as frequent in homeless young people around the time of an unintentional OD when compared to those with no OD.17 Our findings are partially consistent with those of Burns and colleagues who showed OD to be linked to hopelessness, but not self-injurious behavior.11 Depression is a replicated risk factor associated with OD in adults31 and our findings coupled with the existing literature suggest mood dysregulation may play a role in OD risk in young people as well.

Although limited by a small sample size, it is notable that there were no identifiable differences in substance use or psychiatric characteristics between young people with non-fatal and fatal OD who received treatment. Interestingly, in other longitudinal community samples of young people, non-fatal and fatal ODs were not examined in the same sample.9,14–17 It is important to examine non-fatal and fatal OD in similar groups of young people to identify relevant risk factors or characteristics that specifically contribute to fatal OD that could subsequently be targeted for prevention.

The identification of predictors of OD in young people with SUD who received treatment has important clinical implications. Young people with SUD may be more vulnerable to OD in the first year before and after presenting for treatment, and could benefit from close monitoring when they present for treatment. Since young people with SUD have difficulty engaging in treatment it is important that developmentally informed treatment be provided to optimize engagement and retention in treatment. Furthermore, since differences exist in the degree of psychiatric co-morbidity present between adolescent and adult onset SUD,32 it is important to continue to evaluate psychiatric predictors of OD that are specific to young people. Considering the association between mood dysregulation and OD risk found in our sample, it is also important to assess and treat co-occurring mood disorders in young people with SUD.

There are several important methodological limitations of our study that limit generalizations from the findings. The young people who experienced a fatal OD in our sample were not evaluated in the same time frame (2012 to 2013) as the young people with no OD and non-fatal OD. It is possible that changes in the drug supply such as the introduction of fentanyl may have changed risk factors associated with substance use in the fatal OD group. However, since the region of the Northeast that the sample was derived from has had fentanyl present for some time (32% of opioid OD deaths in 2013–2014 involved fentanyl33), changes in the drug supply were likely relatively negligible for this sample. Our data were derived retrospectively in a systematic review of consecutive medical records and was limited to the available information in the medical record within our health system. It is possible that patients experienced OD that were documented outside of our health system and were not captured in our review. Since this was not a prospective longitudinal study, variables that may have impacted OD risk including recent incarceration and use of substances alone were not captured, and a systematic assessment of substances involved in OD was also not available. Furthermore, we also had limited information regarding the details of the fatal ODs including intentionality and substances involved in the OD. Most of the young people in the sample did not engage continuously in treatment which limited our ability to quantify the amount of time an individual was actively engaged in treatment versus overall duration of treatment based on first and last contact with our system. Our data were also derived from treatment-seeking young people who engaged in treatment and may not generalize to young people not seeking treatment and/or those who do not engage in treatment. We describe a heterogeneous sample and our sample size for OD was relatively small which limited our statistical power. For this reason, we reported odds ratios in addition to p-values to evaluate the magnitude of effect for each outcome. Furthermore, we performed stepwise logistic regression to identify the most robust predictors of OD. Lastly, since our sample was mostly Caucasian the findings may not generalize to other racial and ethnic groups.

Despite these limitations our findings from a sample of young people with SUD who received evidence-based outpatient treatment suggests individuals with characteristics of a more severe SUD, especially those with intravenous drug use, and mood dysregulation should be closely monitored for OD in the first year after they seek treatment. Future prospective longitudinal studies of young people seeking-treatment that monitor for non-fatal and fatal OD are needed to gather more systematic and proximal information on risk factors to guide clinicians working with this high-risk population.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Massachusetts General Hospital Louis V. Gerstner III Research Scholar Award, Boston MA, USA and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Physician Scientist in Substance Abuse Award, 5K12DA000357–17, Washington D.C., USA, both received by Dr. Amy Yule.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

Amy Yule, MD: Dr. Amy Yule received grant support from the Massachusetts General Hospital Louis V. Gerstner III Research Scholar Award from 2014 to 2016. Dr. Yule is currently receiving funding through the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Physician Scientist Program in Substance Abuse 5K12DA000357–17. She was a consultant to the Phoenix House from 2015 to 2017 and is currently a consultant to the Gavin House (clinical services).

Timothy Wilens, MD: Dr. Timothy Wilens receives or has received grant support from the following sources: NIH(NIDA). Dr. Timothy Wilens is or has been a consultant for: Alcobra, Neurovance/Otsuka, KemPharm, and Ironshore. Dr. Timothy Wilens has a published books: Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids (Guilford Press); and co/edited books ADHD in Adults and Children (Cambridge University Press), Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry (Elsevier) and Massachusetts General Hospital Psychopharmacology and Neurotherapeutics (Elsevier. Dr. Wilens is co/owner of a copyrighted diagnostic questionnaire (Before School Functioning Questionnaire). Dr. Wilens is Chief, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and (Co) Director of the Center for Addiction Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. He serves as a clinical consultant to the US National Football League (ERM Associates), U.S. Minor/Major League Baseball; Phoenix/Gavin House and Bay Cove Human Services.

Nicholas W. Carrellas, BA, Maura DiSalvo, MPH, Rachael M. Lyons, BS, James W. McKowen, PhD, Jessica E. Nargiso, PhD, Brandon G. Bergman, PhD, John F. Kelly, PhD: Nothing to disclose at this time.

References

- 1.Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993–2009. PloS one 2013;8(2):e54496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2016;64(50–51):1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S. Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, Cocaine, and Psychostimulants - United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2018;67(12):349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2018;67(5152):1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady JE, Giglio R, Keyes KM, DiMaggio C, Li G. Risk markers for fatal and non-fatal prescription drug overdose: a meta-analysis. Inj Epidemiol 2017;4(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, Warmer M. Drug Overdose Deaths Among Adolescents Aged 15–19 in the United States: 1999–2015. NCHS data brief 2017(282):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2016 CDC WONDER Online Database: National Center for Health Statistics;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF. Transitional aged youth: a new frontier in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52(9):887–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman SG, Cheng Y, Kral AH. Prevalence and correlates of opiate overdose among young injection drug users in a large U.S. city. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;88(2–3):182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva K, Schrager SM, Kecojevic A, Lankenau SE. Factors associated with history of non-fatal overdose among young nonmedical users of prescription drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;128(1–2):104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns JM, Martyres RF, Clode D, Boldero JM. Overdose in young people using heroin: associations with mental health, prescription drug use and personal circumstances. Med J Aust 2004;181(7 Suppl):S25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chahua M, Sordo L, Barrio G, et al. Non-fatal opioid overdose and major depression among street-recruited young heroin users. Eur Addict Res 2014;20(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;80(3):297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans JL, Tsui JI, Hahn JA, Davidson PJ, Lum PJ, Page K. Mortality among young injection drug users in San Francisco: a 10-year follow-up of the UFO study. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175(4):302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley ED, Evans JL, Hahn JA, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Multiple Drug Use and Overdose Among Young People Who Inject Drugs. Am J Public Health 2016;106(5):915–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra G, Wood E, Nguyen P, Kerr T, DeBeck K. Drug use patterns predict risk of non-fatal overdose among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;153:135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richer I, Bertrand K, Vandermeerschen J, Roy E. A prospective cohort study of non-fatal accidental overdose among street youth: the link with suicidal ideation. Drug Alcohol Rev 2013;32(4):398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werb D, Kerr T, Lai C, Montaner J, Wood E. Nonfatal overdose among a cohort of street-involved youth. J Adolesc Health 2008;42(3):303–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yule AM, Carrellas NW, Fitzgerald M, et al. Risk Factors for Overdose in Treatment-Seeking Youth With Substance Use Disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MT, Garnick DW, O’Brien PL, et al. Adolescent treatment initiation and engagement in an evidence-based practice initiative. J Subst Abuse Treat 2012;42(4):346–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garnick DW, Lee MT, Horgan CM, Acevedo A, Washington Circle Public Sector W. Adapting Washington Circle performance measures for public sector substance abuse treatment systems. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;36(3):265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilens TE, McKowen J, Kane M. Transitional-aged youth and substance use: teenaged addicts come of age. Contemporary Pediatrics 2013.

- 23.Raistrick D, Bradshaw J, Tober G, Weiner J, Allison J, Healey C. Development of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ): a questionnaire to measure alcohol and opiate dependence in the context of a treatment evaluation package. Addiction 1994;89(5):563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins LM, Banta-Green CJ, Maynard C, et al. Risk factors for nonfatal overdose at Seattle-area syringe exchanges. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 2011;88(1):118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grau LE, Green TC, Torban M, et al. Psychosocial and contextual correlates of opioid overdose risk among drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Harm reduction journal 2009;6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coffin PO, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, Ompad D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Identifying injection drug users at risk of nonfatal overdose. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 2007;14(7):616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin E, Corcoran P, Cassidy L, O’Carroll A, Perry IJ, Bonner B. Characteristics of hospital-treated intentional drug overdose in Ireland and Northern Ireland. BMJ open 2014;4(7):e005557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR. Trends in Receipt of Buprenorphine and Naltrexone for Opioid Use Disorder Among Adolescents and Young Adults, 2001–2014. JAMA pediatrics 2017;171(8):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Rodean J, et al. Receipt of Timely Addiction Treatment and Association of Early Medication Treatment With Retention in Care Among Youths With Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA pediatrics 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bartoli F, Carra G, Brambilla G, et al. Association between depression and non-fatal overdoses among drug users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;134:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu LT, Gersing K, Burchett B, Woody GE, Blazer DG. Substance use disorders and comorbid Axis I and II psychiatric disorders among young psychiatric patients: findings from a large electronic health records database. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45(11):1453–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somerville NJ, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, et al. Characteristics of Fentanyl Overdose - Massachusetts, 2014–2016. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2017;66(14):382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]