Abstract

Background & Aims:

Gender disparities exist in outcomes among patients with cirrhosis. We sought to evaluate the role of gender on hospital course and in-hospital outcomes in patients with cirrhosis to help better understand these disparities.

Study:

We analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), years 2009–2013, to identify patients with any diagnosis of cirrhosis. We calculated demographic and clinical characteristics by gender, as well as cirrhosis complications. Our primary outcome was inpatient mortality. We used logistic regression to associate baseline characteristics and cirrhosis complications with inpatient mortality.

Results:

Our cohort included 553,017 patients with cirrhosis admitted from 2009–2013. Women made up 39% of the cohort; median age was 57 with 66% non-Hispanic White. Women were more likely than men to have non-cirrhosis comorbidities, including diabetes and hypertension, but were less likely to have most cirrhosis complications, including ascites and variceal bleeding. Women were more likely than men to have acute bacterial infections (34.9% vs 28.2%, p < 0.001), and were less likely than men to die in the hospital on univariable (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.86 – 0.90, p < 0.001) and multivariable (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.83 – 0.88, p < 0.001) analysis.

Conclusions:

In patients hospitalized with cirrhosis, women have lower rates of hepatic decompensating events and higher rates of non-hepatic comorbidities and infections, resulting in lower in-hospital mortality. Understanding differences in indications for and disposition following hospitalization may help with the development of gender-specific cirrhosis management programs to improve long-term outcomes in women and men living with cirrhosis.

Keywords: sex differences, hospital admission, chronic liver disease

INTRODUCTION

It is well-established in the literature that the natural history of chronic liver disease differs by gender. Women are significantly less likely to have most types of chronic liver disease, with approximately 55–70% of cases occurring in men.1–4 In addition, early in the course of chronic liver disease, women are thought to have a more favorable clinical course than men. Women are more likely than men to spontaneously clear hepatitis C virus, 5 and are less likely to experience flares and reactivation of hepatitis B. 6,7 Female sex is a protective factor in the progression of liver fibrosis due to both viral hepatitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), particularly in premenopausal women. 8–10 This difference in fibrosis progression is thought to be due to the protective effects of sex hormones and decreased incidence of cofactors for fibrosis progression. 10,11 Women also have significantly lower incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma than men. 12

In contrast, at the end stages of chronic liver disease, women appear to experience a more severe disease course than men. Women have higher rates of mortality on the liver transplant waitlist and lower rates of transplant. 13–15 In addition, women are more likely to be delisted because of becoming “too sick” for transplant.13,16 Women also have higher rates of fibrosis progression after liver transplant.17 The reasons behind this “reversal” in gender disparities is unknown.

Hospitalizations, episodes in which patients are the most acutely ill, are emerging as an important measure of disease burden in chronic liver disease. 18 We believed that investigating hospitalizations could provide insights into why women fare worse at the very end stages of chronic liver disease. We hypothesized that women with cirrhosis, particularly those with decompensated disease, would be more likely to be hospitalized with cirrhosis-related complications than men and would have worse outcomes. Leveraging the power of a large nationwide database, we aimed to determine whether there are gender differences in hospital course and inpatient mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of data

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study using discharge data from the National Inpatient Sample and Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), part of the Heathcare Cost and Utilization Project created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, years 2009–2013.19,20 The NIS is the largest publicly available inpatient care database in the United States, and includes a 20% stratified sample of discharges from approximately 1000 non-federal hospitals. Each discharge record from the NIS contains associated patient demographic data, primary and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses, up to 15 procedural codes, and basic hospital information. Each observation in the data set is a unique hospitalization episode ending with patient death or discharge.

Study population

The study sample included patients 18 years or older with any discharge diagnosis of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis hospitalizations were identified by one or more of the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: alcoholic cirrhosis 571.2, cirrhosis without alcohol 571.5, or biliary cirrhosis 571.6. This combination of ICD-9-CM codes has previously been shown to have a positive predictive value of 90% and a negative predictive value of 87%.21

Variables

The primary predictor was gender, as classified in the NIS database. In addition, other patient-level data included patient age, race/ethnicity, median household income for patient zip code, and primary payer. Hospital region (Northeast, South, Midwest, West) was also analyzed.

We used the Deyo modification of the Charlson Index as a proxy for patient comorbidity, with additional adjustments to account for liver disease. 22–24 We stratified the Charlson Index into 3 groups to represent the degree of comorbidity: Mild (score = 0), moderate (score = 1–3), and severe (score > 3). In addition, we used the diagnosis Clinical Classification Software (CCS) system to capture specific patient comorbidities, such as diabetes, cancer (excluding primary liver cancer), and coronary disease. Developed by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, the single-level CCS classifies ICD-9 diagnoses and conditions into 261 clinically meaningful categories. 25,26

Cirrhosis etiology was determined using ICD-9 codes for alcoholic cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for list all ICD-9 codes), with the remainder of cases of cirrhosis labeled as “other”. Cirrhosis complications were defined as the following: ascites, variceal bleed, nonbleeding varices, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). ICD-9 codes for these complications have also been validated, and are listed in Supplemental Digital Content 1. 26–28 We also evaluated whether there were differences between women and men in rates of cirrhosis-related versus comorbidity-related principal diagnoses (i.e. first diagnosis listed in the database, which has been indicated as principal problem during hospitalization).In addition to SBP, other types of infection were captured using validated ICD-9 codes for sepsis, bacteremia, urinary tract infection (UTI), cellulitis/abscess, and pneumonia (See Supplemental Digital Content 1). 29–31

We used the Baveno IV consensus criteria as a measure of decompensated liver disease, where patients were categorized as stage 1 (no esophageal varices or ascites), stage 2 (esophageal varices, no ascites or bleeding), stage 3 (ascites, with or without esophageal varices), or stage 4 (gastrointestinal bleeding with or without ascites). Stages 3 and 4 disease represented decompensated cirrhosis. This method has been used in previous studies to define decompensation. 28,32 Sensitivity analyses were also performed using alternate definitions of decompensation, based on ICD-9-CM codes for decompensation events (A. Baveno Stage 3/4; B. Ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or bleeding esophageal varies; C. B + nonbleeding varices; D. C + hepatorenal syndrome or SBP). To explore whether cirrhosis-related procedures differed by gender, we also utilized validated ICD-9-CM procedure codes to identify paracentesis, thoracentesis, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures, and the procedure-based CCS to identify upper endoscopies. 33 Procedures were compared in all women and men, and separately in those with particular complications that would warrant such procedures. Upper endoscopy was captured using the procedure CCS system.

Our primary outcome was inpatient mortality. Our secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay, liver transplantation during hospitalization, and discharge with rehabilitation services. Liver transplantation during hospitalization was determined using one of the ICD-9 procedure codes for liver transplant of 50.51 and 50.59. Discharge with rehabilitation services included patients transferred to skilled nursing, intermediate care, or hospice facilities, and patients discharged home with home health care services.

Several subgroup and exploratory analyses were performed to better characterize our primary outcome of inpatient mortality and secondary outcome of liver transplantation. First, we stratified by gender to determine whether predictors of mortality differed in women and men. Second, we determined how specific types of infection were associated with inpatient mortality, again stratified by gender, in order to account for differences in rates of infection between women and men. Third, we looked at differences in rates of decompensation and mortality in patients with or without active alcohol use. Fourth, we explored whether rates of inpatient mortality or liver transplantation differed by decompensation status.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared between groups by chi-square and Fisher’s exact testing. Continuous variables were presented as medians with respective interquartile ranges (IQR) and compared between groups by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests given non-normal distributions. We determined risk factors for inpatient mortality, discharge with rehabilitation services, and liver transplantation using multivariable logistic regression analysis. As length of stay was a count variable with evidence of overdispersion, negative binomal regression was used to predict average length of stay for women and men. Models were adjusted for demographic, clinical, and hospital predictors that were significant (p<0.05) in single variable regression models. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the threshold of significance in multivariable models based on the number of hypotheses tested in each multivariable model, in order to avoid the multiple comparisons problem. Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 statistical software (College Station, Texas). This study was approved by the institutional review board at University of California-San Francisco.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample of 553,017 patients with cirrhosis are shown in Table 1. Of these patients, 39.0% were women; median age was 57 with 65.5% non-Hispanic White. Medicare was the primary payer for approximately 44% of the cohort. Women were slightly older than men with median age [interquartile range (IQR)] 59 years (52 – 70) vs 57 years (51 – 65), and were more likely to have Medicare as primary payer (48.6% vs 41.0%). Women were less likely than men to be hospitalized in the Northeast but more likely to be hospitalized in the Midwest and the South.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Women and Men with Cirrhosis1

| Total N = 553,017 | Women n = 215,667 39% | Men n = 337,317 61% | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 57 (51–67) | 59 (52–70) | 57 (51–65) | <0.001 | |

| Race | White | 65.5 | 66.5 | 64.8 | <0.001 |

| Black | 11.0 | 11.4 | 10.8 | ||

| Hispanic | 17.1 | 15.7 | 18.0 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 | ||

| Native American | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | ||

| Other | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.3 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.2 | <0.001 | |

| Cancer (non-liver) | 12.2 | 13.6 | 11.4 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 35.7 | 38.7 | 33.7 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 48.8 | 49.7 | 48.3 | <0.001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 16.2 | 14.2 | 17.6 | <0.001 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 14.9 | 15.7 | 14.3 | <0.001 | |

| Stroke | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 16.0 | 15.7 | 16.2 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 18.6 | 18.5 | 18.7 | 0.091 | |

| Psychiatric illness | 23.1 | 28.1 | 20.0 | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol use disorder | 41.2 | 28.7 | 49.3 | <0.001 | |

| Drug use disorder | 9.4 | 7.5 | 10.6 | <0.001 | |

| Charlson Index | Mild | 30.9 | 29.1 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 53.0 | 55.1 | 51.7 | ||

| Severe | 16.1 | 15.7 | 16.3 | ||

| Other | |||||

| Median income | <$24,999 | 33.6 | 33.3 | 33.9 | <0.001 |

| $25,000 – $34,999 | 25.9 | 26.1 | 25.8 | ||

| $35,000 – $44,999 | 23.3 | 23.4 | 23.2 | ||

| >$45,000 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 17.1 | ||

| Primary payer | Medicare | 44.0 | 48.6 | 41.0 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 22.1 | 21.9 | 22.3 | ||

| Private Insurance | 20.9 | 19.9 | 21.6 | ||

| Self-pay | 7.9 | 6.0 | 9.0 | ||

| Other | 5.2 | 3.6 | 6.2 | ||

| Hospital region | Northeast | 18.4 | 17.3 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 19.2 | 20.1 | 18.6 | ||

| South | 38.7 | 39.0 | 38.6 | ||

| West | 23.6 | 23.5 | 23.6 | ||

Data presented as percent or median (IQR)

Comorbidities

Although women and men had clinically similar severity of illness based on Charlson Index, women were significantly more likely than men to have most non-cirrhosis chronic diseases, including cancer, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure and stroke. Men were more likely to have coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rates of chronic kidney disease were similar in women and men. While women were more likely to have concurrent psychiatric illness, they were less likely than men to have concurrent alcohol or drug use disorders. We also examined principal diagnosis, and did not find any clinically significant differences between women and men.

Cirrhosis complications and related procedures

There were gender differences in the etiology and frequency of complications of cirrhosis, as shown in Table 2. Women were less likely than men to have liver disease due to alcohol (24.1% vs 38.7%, p < 0.001) and viral hepatitis (27.6% vs 35.2%, p < 0.001), but were more likely to have autoimmune hepatitis (2.5% vs 0.4%, p < 0.001) and other/unspecified etiology of cirrhosis (45.7% vs 25.7%, p < 0.001). Women were also significantly less likely to have decompensated cirrhosis as defined by Baveno IV criteria than men (34.0% vs 38.8%, p < 0.001), and were also less likely to have most complications of ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. On sensitivity analysis, regardless of how decompensation was defined, women had persistently lower rates of decompensation than men. As a result, they were less likely than men to undergo paracentesis (17.6% vs 20.6%, p < 0.001), upper endoscopy (12.8% vs 13.0%, p = 0.02) and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) (0.8% vs 1.0%, p < 0.001) during hospitalization. Hepatic encephalopathy, by contrast, was the only cirrhosis complication that was more common in women than men (17.8% vs 16.8%, p < 0.001). On subgroup analysis, alcohol use disorders—and in particular, an alcohol-related principal diagnosis—were associated with significantly increased risk of decompensation. However, even among those with alcohol use, women had lower rates of decompensation than men.

Table 2.

Cirrhosis etiology, complications, and inpatient procedures among hospitalized women and men

| Total N = 553,017 | Women n = 215,667 39% | Men n = 337,317 61% | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis etiology | Alcohol | 33.0 | 24.1 | 38.7 | <0.001 |

| Viral | 32.3 | 27.6 | 35.2 | ||

| Autoimmune | 1.2 | 2.5 | 0.4 | ||

| Other | 33.5 | 45.7 | 25.7 | ||

| Ascites | 33.3 | 31.1 | 34.6 | <0.001 | |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 3.6 | 3.2 | 3.9 | <0.001 | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.9 | <0.001 | |

| Variceal bleed | 5.9 | 4.6 | 6.8 | <0.001 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17.2 | 17.7 | 16.8 | <0.001 | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 36.9 | 34.0 | 38.8 | <0.001 |

Data presented as percent

Bacterial infections

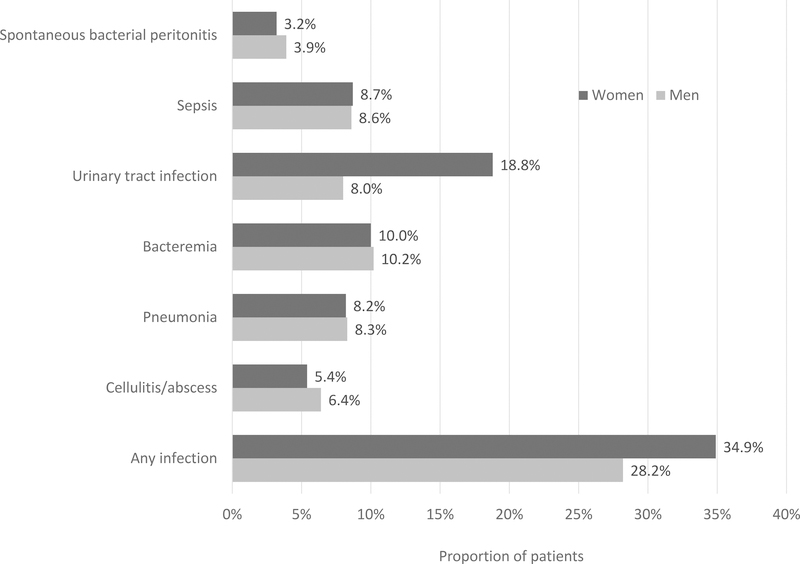

Acute bacterial infections (including SBP) were present in nearly one third of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, as shown in Figure 1, with urinary tract infection and bacteremia being the most common types of infection. Women were significantly more likely than men to have any type of bacterial infection (34.9% vs 28.2%, p < 0.001). Urinary tract infections were present in 18.8% of women and 8.0% of men (p < 0.001) during hospitalization. Bacteremia was present in approximately 10% of both women and men (p = 0.056). Cellulitis and abscesses were also common, present in 5.4% of women and 6.4% of men (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Proportion of women and men hospitalized with cirrhosis with additional diagnosis of bacterial infection during hospitalization.

Note: all differences are statistically significant, p < 0.05

Inpatient mortality

Regarding our primary outcome of inpatient mortality, women were significantly less likely to die during hospitalization than men (5.7% vs 6.4%, p < 0.001). On univariable logistic regression, female gender was associated with a decreased risk of death (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.86 – 0.90, p < 0.001) (Table 3). While many other variables were statistically significant, other factors that were independently associated with the highest odds of death during hospitalization were hepatorenal syndrome (OR 7.53, 95% CI 7.29 – 7.78, p < 0.001), infection (OR 3.91, 95% CI 3.82 – 4.00, p < 0.001), SBP (OR 3.41, 95% CI 3.28 – 3.55, p < 0.001), and hepatic encephalopathy (OR 2.17, CI 2.12 – 2.23, p < 0.001). Liver transplantation during hospitalization was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital death (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.45 – 0.62, p < 0.001). Female gender remained associated with decreased risk of in-hospital on multivariable logistic regression, after adjustment for multiple demographic and clinical characteristics (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.83 – 0.88, p < 0.001), as shown in Table 3. On subgroup analysis, the same clinical characteristics predicted mortality in men and in women on univariable and multivariable analyses.

Table 3.

Predictors of inpatient mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Female gender | 0.88 | 0.86 – 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.86 | 0.83 – 0.88 | <0.001 |

| Age per year | 1.01 | 1.01 – 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.02 – 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | 1.07 | 1.03 – 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.13 – 1.22 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.92 – 0.98 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.88 – 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Asian | 1.33 | 1.24 – 1.43 | <0.001 | 1.24 | 1.14 – 1.34 | <0.001 |

| Income <$24,000 | 1.00 | 0.98 – 1.03 | 0.87 | |||

| Primary payer | ||||||

| Medicare | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Medicaid | 0.98 | 0.95 – 1.01 | 0.106 | 1.27 | 1.23 – 1.32 | <0.001 |

| Private insurance | 1.06 | 1.03 – 1.09 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 1.24 – 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Midwest | 0.89 | 0.86 – 0.93 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.83 – 0.91 | <0.001 |

| South | 0.99 | 0.95 – 1.02 | 0.483 | |||

| West | 1.11 | 1.07 – 1.15 | <0.001 | |||

| Charlson Index | 1.11 | 1.10 – 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.11 – 1.12 | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis etiology | ||||||

| Alcohol | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Viral | 0.74 | 0.72 – 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.84 – 0.90 | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune | 0.68 | 0.61 – 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.77 | 0.68 – 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.77 | 0.75 – 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.76 – 0.82 | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 1.73 | 1.69 – 1.76 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.20 – 1.26 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 3.41 | 3.28 – 3.55 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 1.14 – 1.25 | <0.001 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 7.53 | 7.29 – 7.78 | <0.001 | 5.21 | 5.01 – 5.40 | <0.001 |

| Variceal bleed | 1.77 | 1.70 – 1.84 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 2.14 – 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 2.17 | 2.12 – 2.23 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.66 – 1.76 | <0.001 |

| Any infection | 3.91 | 3.82 – 4.00 | <0.001 | 3.58 | 3.49 – 3.67 | <0.001 |

| Liver transplant | 0.53 | 0.45 – 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.26 – 0.38 | <0.001 |

Odds ratio (OR); Confidence interval (CI); Adjusted odds ratio (aOR); spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).

Given differential rates of infection between women and men, we performed an exploratory analysis looking at risk of death by gender for individual types of infection. We found that odds of inpatient mortality were higher in women with most types of infection (SBP, sepsis, bacteremia, pneumonia and cellulitis) than among men with these infections. Women with UTIs however had significantly decreased odds of death compared to men with UTIs. All interactions between gender and infection type on the primary outcome of inpatient mortality were significant (see Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Secondary outcomes

Women were also less likely than men to undergo liver transplantation during hospitalization, with 0.7% of women vs 0.9% of men undergoing transplant (p < 0.001). Women were less than 80% as likely as men to undergo liver transplantation on univariable logistic regression (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.72 – 0.82, p < 0.001), and this disparity persisted after adjustment for clinical and demographic characteristics (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.86, p < 0.001). On subgroup analysis by decompensation status, among only patients with decompensated cirrhosis, female gender remained associated with decreased odds of liver transplant during hospitalization (aOR 0.83, 95% CI 0.76 – 0.92, p < 0.001).

Women in our cohort were more likely than men to be discharged to either a skilled nursing facility or home with rehabilitation services (33.3% vs 27.7%, p < 0.001). Female gender was also associated with increased risk of discharge with rehab services on both univariable (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.29 – 1.32) and multivariable logistic regression (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.12–1.15, p < 0.001).

Length of stay was clinically similar between women and men with median (IQR) 4 (2–7) days for both genders. On univariable negative binomial regression, female gender was associated with slightly shorter length of stay compared with men in both univariable (IRR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99 – 1.00, p = 0.03) and multivariable (IRR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97 – 0.98, p < 0.001) analysis.

DISCUSSION

Hospitalizations are a critically important area of research in chronic liver disease as they represent the intersection between the natural acute presentation of disease and the failure of the healthcare system to prevent decompensation. For patients with cirrhosis, the end stage of chronic liver disease, hospitalizations and readmissions are associated with a substantially increased risk of death despite similar liver disease severity. 34,35 Moreover, recent data suggest that inpatient morbidity is higher and hospitalization rates are rising faster than in many other chronic diseases. 36 Given the association between hospitalizations and death, we reasoned that investigating gender differences in hospitalizations would yield insights into the well-recognized gender disparities in death among decompensated patients with cirrhosis. 13,14,16,17,37 Although we hypothesized that women with cirrhosis would be more likely to die in the hospital due to cirrhosis complications, we found the opposite to be true: women were, in fact, less likely to be hospitalized with typical complications of cirrhosis (e.g., ascites, variceal bleeding, and SBP) and less likely than men to die during the hospitalization.

What might explain these findings? Prior studies have demonstrated a male predominance of portal hypertensive complications. 38 Our findings that among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, women had lower rates of most cirrhosis complications, and of Baveno Class 3 and 4 disease support this. Thus, it is possible that the natural history of decompensation and development of portal hypertensive complications differs by gender. While prior research has shown decreased rates of histologic fibrosis progression in women, 8 gender differences in rates or patterns of clinical decompensation have not been established. Our data suggest that differential rates of ongoing liver injury – including by cofactors such as active alcohol use – explain some but not all of the gender difference we observed in hepatic decompensation. The poor prognosis of decompensated cirrhosis then provides a reasonable explanation for the higher rates of in-hospital mortality seen among men versus women.

Although the men in our cohort had higher rates of portal hypertensive complications, the women in our cohort had higher rates non-hepatic comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, factors that are strongly associated with hospitalization in the general population. 39–41 Such comorbidities may be contributing to hospitalizations in women prior to the development of significant portal hypertension. It is also possible that there exist gender differences in patterns of overall healthcare utilization – i.e., the threshold for admission is different for a woman than a man. The literature outside of hepatology support our findings, as hospitalized women have also been shown to have higher rates of multimorbidity than men, and suffer from chronic conditions that that lead to impairment in activities of daily living and significant disability, but to lower rates of short-term mortality. 42,43

Interestingly, acute bacterial infections were more common in women, despite lower rates of portal hypertension, which is a well-established risk factor for infection. 44–46 Bacterial infections are also a well-known risk factor for mortality in cirrhosis. Interestingly, infections were a stronger predictor of inpatient mortality in women than men. Despite this, women in our cohort were less likely to die in the hospital than men. Perhaps this is due to the fact that much of the gender difference in bacterial infections was driven by urinary tract infections, which are associated with lower risk of mortality than most other types of bacterial infections, particularly in women. In addition, UTIs may also be the infectious process most susceptible to erroneous coding (i.e. urinary tract colonization). It is also important to note that bacterial infections are also one of the most common reasons for admission in the general population. 47,48 Thus, the phenotype of the hospitalized women with cirrhosis seems more similar to the hospitalized woman without cirrhosis than to the hospitalized man with cirrhosis.

This gender difference in hospital course translates to differences in disposition as well. Although women with cirrhosis are less likely to die or receive a liver transplant during hospitalization, they have higher rates of discharge to post-acute care institutions and with rehabilitation services. This is consistent with prior research which has found that women are more likely to live alone than men and are less likely to have caregivers, which likely leads to different thresholds for hospitalization and discharge. 49,50

We acknowledge the following limitations to this study. First, the NIS lacks full clinical detail including laboratory data, limiting our ability to calculate MELDNa and Child-Pugh scores to compare severity of illness. However, prior studies have utilized and validated ICD-9 codes to identify cirrhosis complications and estimate decompensation as a marker of severity of liver disease. 26–28,32 Still, there remain some complications, such as hepatic encephalopathy, which may be particularly susceptible to coding errors, given difficulty in diagnosing low-grade encephalopathy and in distinguishing it from other causes of altered mental status in hospitalized patients. Second, the NIS does not provide patient identifiers, so we are unable to track readmissions by the same patient. As readmissions are common in cirrhosis, our data may capture the same patients during multiple admissions. In addition, given the trend toward shorter hospitalizations in women, a better understanding of short-term post-hospital outcomes, including readmissions, will be important in fully understanding gender disparities in cirrhosis hospitalizations. Finally, this study only includes data about acute hospitalization episodes, so we cannot measure longer term outcomes or trends in health resource utilization. Our findings should be validated in a prospective cohort that allows us to capture more granular clinical data for patients during and after hospitalization, including information on patterns of clinical decompensation, healthcare utilization (including readmissions) and longer-term mortality. Studies that incorporate more difficult to measure factors, such as disability and social support, may provide additional insight into differential rates of hospitalization and liver transplant between women and men.

Despite these limitations, our study expands upon the current knowledge of gender disparities in patients with cirrhosis. Our principle findings provide important insight into why women with cirrhosis fare worse at the end-stages of disease. With regard to liver transplantation, lower rates of hepatic decompensating events in women likely result in fewer indications and lower priority for transplant. In addition, higher rates of non-hepatic comorbidities, infections, and resulting disability among women may, in fact, be barriers to liver transplantation, or may result in death prior to listing or while on the waitlist. More broadly, our findings highlight the need for additional studies further exploring differences in hospital course and post-discharge outcomes between men and women with cirrhosis – particularly in the setting of increasing cirrhosis incidence and burden on the United States healthcare system – with the ultimate goal of identifying potential opportunities for intervention to help modify the course of all patients with cirrhosis. The development of gender-specific cirrhosis management programs – focused on interventions to manage the interaction between cirrhosis and other common comorbidities, improving physical function both before and during hospitalization, and post-acute discharge programs to facilitate resumption of independent living – would target differential needs of women and men living with cirrhosis, with the ultimate goal of improving long-term outcomes in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT

Supplemental Digital Content 1 & 2

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim WR, Brown RS, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. In: Vol 36 2002:227–242. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratib S, West J, Crooks CJ, Fleming KM. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in England, a cohort study, 1998–2009: a comparison with cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(2):190–198. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Study Group, Lonardo A, Bellentani S, et al. Epidemiological modifiers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Focus on high-risk groups. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47(12):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(8):690–696. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grebely J, Page K, Sacks-Davis R, et al. The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):109–120. doi: 10.1002/hep.26639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu CM, Liaw YF. Predictive factors for reactivation of hepatitis B following hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(5):1458–1465. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar M, Chauhan R, Gupta N, Hissar S, Sakhuja P, Sarin SK. Spontaneous increases in alanine aminotransferase levels in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1272–1280. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349(9055):825–832. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48(2):335–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang JD, Abdelmalek MF, Pang H, et al. Gender and menopause impact severity of fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1406–1414. doi: 10.1002/hep.26761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2371–2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai JC, Terrault NA, Vittinghoff E, Biggins SW. Height contributes to the gender difference in wait-list mortality under the MELD-based liver allocation system. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2658–2664. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Sex-based disparities in liver transplant rates in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(7):1435–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cullaro G, Sarkar M, Lai JC. Sex-based disparities in delisting for being “too sick” for liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1214–1219. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JC, Verna EC, Brown RS, et al. Hepatitis C virus-infected women have a higher risk of advanced fibrosis and graft loss after liver transplantation than men. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):418–424. doi: 10.1002/hep.24390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Serag HB. Hospitalizations for Chronic Liver Disease: Time to Intervene at Multiple Levels. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):607–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 20.HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 21.KRAMER JR, DAVILA JA, MILLER ED, RICHARDSON P, GIORDANO TP, EL-SERAG HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.4598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundaram V, Jalan R, Ahn JC, et al. Class III obesity is a risk factor for the development of acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69(3):617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Fortin M, et al. Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0155-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg D, Lewis J, Halpern S, Weiner M, Re Lo V. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(7):765–769. doi: 10.1002/pds.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Re VL III, Lim JK, Goetz MB, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and liver-related laboratory abnormalities to identify hepatic decompensation events in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):689–699. doi: 10.1002/pds.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gohil SK, Cao C, Phelan M, et al. Impact of Policies on the Rise in Sepsis Incidence, 2000–2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(6):695–703. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine PJ, Elman MR, Kullar R, et al. Use of electronic health record data to identify skin and soft tissue infections in primary care settings: a validation study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato R, Gomez Rey G, Nelson S, Pinsky B. Community-acquired pneumonia episode costs by age and risk in commercially insured US adults aged ≥50 years. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(3):251–258. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0026-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.May FP, Rolston VS, Tapper EB, Lakshmanan A, Saab S, Sundaram V. The impact of race and ethnicity on mortality and healthcare utilization in alcoholic hepatitis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0544-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.HCUP Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks CJ, Aithal GP, West J. 1 and 5 year survival estimates for people with cirrhosis of the liver in England, 1998–2009: a large population study. J Hepatol. 2014;60(2):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scaglione SJ, Metcalfe L, Kliethermes S, et al. Early Hospital Readmissions and Mortality in Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis Enrolled in a Large National Health Insurance Administrative Database. J Clin Gastroenterol. April 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asrani SK, Kouznetsova M, Ogola G, et al. Increasing Health Care Burden of Chronic Liver Disease Compared With Other Chronic Diseases, 2004–2013. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):719–729.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathur AK, Chakrabarti AK, Mellinger JL, et al. Hospital resource intensity and cirrhosis mortality in United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(10):1857–1865. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i10.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jepsen P, Ott P, Andersen PK, Sørensen HT, Vilstrup H. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1675–1682. doi: 10.1002/hep.23500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh JA, Yu S. Emergency Department and Inpatient Healthcare utilization due to Hypertension. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):303. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1563-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bo S, Ciccone G, Grassi G, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes had higher rates of hospitalization than the general population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(11):1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comino EJ, Harris MF, Islam MDF, et al. Impact of diabetes on hospital admission and length of stay among a general population aged 45 year or more: a record linkage study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corrao S, Santalucia P, Argano C, et al. Gender-differences in disease distribution and outcome in hospitalized elderly: data from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(7):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goebeler S, Jylhä M, Hervonen A. Use of hospitals at age 90. A population-based study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2004;39(1):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernández J Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35(1):140–148. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Moss M. Cirrhosis as a risk factor for sepsis and death: analysis of the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Chest. 2003;124(3):1016–1020. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gustot T, Durand F, Lebrec D, Vincent J-L, Moreau R. Severe sepsis in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50(6):2022–2033. doi: 10.1002/hep.23264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wier LM, Pfuntner A, Maeda J, Stranges E, Ryan K. HCUP Facts and Figures: Statistics on Hospital-Based Care in the United States 2009, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDermott KW, Elixhauser A, Brief RSS, 2017. Trends in Hospital Inpatient Stays in the United States, 2005–2014.

- 49.Cherepanov D, Palta M, Fryback DG, Robert SA. Gender differences in health-related quality-of-life are partly explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variation between adult men and women in the US: evidence from four US nationally representative data sets. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(8):1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9673-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navaie-Waliser M, Spriggs A, Feldman PH. Informal caregiving: differential experiences by gender. Med Care. 2002;40(12):1249–1259. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036408.76220.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.