Abstract

The genus Allium is one of the largest monocotyledonous genera, containing over 850 species, and most of these species are found in temperate climates of the Northern Hemisphere. Furthermore, as a large number of new Allium species continue to be identified, phylogenetic classification based on morphological characteristics and a few genetic markers will gradually exhibit extremely low discriminatory power. In this study, we present the use of complete chloroplast genome sequences in genome-scale phylogenetic studies of Allium. We sequenced and assembled four Allium chloroplast genomes and retrieved five published chloroplast genomes from GenBank. All nine chloroplast genomes were used for genomic comparison and phylogenetic inference. The chloroplast genomes, ranging from 152,387 bp to 154,482 bp in length, exhibited conservation of genomic structure, and gene organization and order. Subsequently, we observed the expansion of IRs from the basal monocot Acorus americanus to Allium, identified 814 simple sequence repeats, 131 tandem repeats, 154 dispersed repeats and 109 palindromic repeats, and found six highly variable regions. The phylogenetic relationships of the Allium species inferred from the chloroplast genomes obtained high support, indicating that chloroplast genome data will be useful for further resolution of the phylogeny of the genus Allium.

Subject terms: Molecular evolution, Plant evolution

Introduction

The genus Allium is one of the largest monocotyledonous genera, containing over 850 species1–4. Most of these species are found in temperate climates of the Northern Hemisphere and spread widely across the Holarctic region from the dry subtropics to the boreal zone. Allium is characterized by herbaceous geophyte perennials with true bulbs, some of which are borne on rhizomes, and a familiar onion or garlic odour and flavour3. This genus contains many economically important species, including garlic, leek, onion, shallot, bunching onion, chives and Chinese chives, which are cultivated as vegetables or spices, and species used as herbal crops, such as traditional medicines and ornamental plants2,5.

The classification of Allium is clear in high taxonomic categories above genus. This genus is first placed in the family Liliaceae and then in the family Alliaceae of the order Asparagales in APG I and APG II6,7. The APG classification system has now been revised to APG III and APG IV, so the genus Allium becomes a member of the family Amaryllidaceae, subfamily Allioideae, in the new APG classification system8–10. However, at the infrageneric level, the classification of Allium is very complex, often controversial and remains in progress. A brief history of the infrageneric classification of Allium is provided in a number of studies2,11,12. With the development of molecular biological methods, many molecular studies on the classification, phylogeny and origin of Allium have been performed and many improvements have been made1,2,11–21, especially by using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, rps16 intron and matK sequence to understand the evolutionary processes and taxonomic relationships within the genus. The research methods used in those studies are based on morphological characteristics and partial molecular data that are widely used for the classification of new species in this genus2,8,19,20,22,23. All of the above mentioned works have been helpful in establishing and assessing the evolutionary lineages in the genus Allium. However, due to close morphological similarities among species, a wide variety of habitats, traditional classifications based on homoplasious characteristics and a large number of new species, the precise taxonomy of Allium is poorly understood2.

The chloroplast (cp), a key organelle for photosynthesis and carbon fixation in green plants, originates from photosynthetic bacteria that interacted with non-photosynthetic hosts via endosymbiosis24–26. Moreover, cps have their own genomes, and the genetic information is inherited maternally in most angiosperms27,28. Most cp genomes are circular DNA molecules ranging from 120 to 160 kb in length and are highly conserved in terms of gene content and order29–32. These genomes have typical quadripartite structures, in which two identical inverted repeat (IR) segments are separated by either a large or a small single-copy region (LSC and SSC, respectively)33.

Due to its highly conserved genome structure and gene content, moderate evolutionary rate, uniparental inheritance and nearly collinear gene order in most land plants, the cp genome has been used for the generation of genetic markers for phylogenetic classification34–37, divergence dating21,38, and DNA barcoding for molecular identification39,40. With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing, it is now convenient and relatively inexpensive to obtain cp genome sequences, allowing whole-plastome analysis to obtain large amounts of valuable information41 and allowing further extension of phylogenetic analyses based on one or a few loci to whole-genome-based phylogenomic analyses.

Sequencing of the complete cp DNA genome in Allium began in 201342, and to date, five Allium species namely, A. prattii, A. obliquum, A. victorialis, A. sativum, and A. cepa, have been sequenced (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/organelle/). And four species in this genus, namely, A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. sativum, and A. cepa are very important vegetable crops not only in Allium but also in all vegetable crops acccording to the FAOSTAT in 2017 (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC). The total harvested area and the total production are approximately 7.16 million hectares and 133.39 million tonnes, respectively. A global review of major vegetable crops ranks these third in area and fourth in production. Moreover, even in the same species, there are different cytoplasmic types, which make them different in chloroplast genome. For example, Allium cepa has three cytoplasmic types, which is designated as CMS-S (CMS, cytoplasmic male-sterility), CMS-T and N (Normal). The cp genome is expected to be useful not only in the resolving the deeper branches of the phylogeny, but also in DNA barcoding of molecular identification, screening of genetic resources and breeding.

In the present study, we constructed the whole cp genomes of four Allium species, A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. sativum and A. cepa, using next-generation sequencing. The objectives of this study were to 1) establish and characterize the organization of the complete cp genomes from four Allium species, 2) conduct comparative genomic studies by combining the whole cp genomes of other Allium species from GenBank, 3) explore additional molecular markers based on variations in the whole cp genomes, 4) assess the taxonomic positions of Allium species based on the complete cp genomes, 5) serve as a reference for future genome-scale phylogenetic studies of Allium.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly for four Allium species

Four Allium species were sequenced, and 8,255,274–13,393,542 paired-end clean reads were obtained. Three complete cp genomes (A. fistulosum, A. sativum and A. cepa) were directly assembled by NOVOPlasty 2.6.2. A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. was not circularized by NOVOPlasty. We assembled this genome using SPAdes 3.11.1 and visualized it with Bandage 0.8.1. According to the “Depth range” (≥500), five merged nodes were selected and used to align with the reference NC_024813.1 in Mummer 3.23. The nodes for which the order had been determined were linked to two super-contigs based on their overlap (Supplementary Fig. S1). Two pairs of primers (p1, p2 and p3, p4) were designed according to the two gaps and their sites information provided in Supplementary Fig. S1. Then, PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing were conducted to fill these gaps. Last, the complete cp genomic sequences were assembled by SPAdes 3.11.1 with the options of “–trusted-contigs” including five node and two gap sequences. Alternatively, the sequences from the five nodes and two gaps could be linked manually according to the alignment graph (Supplementary Fig. S1). As a result, four complete cp genomes had been assembled by using the data from two sequencing platforms (HiSeq 4000 and 2500) and two read lengths (150 and 100 bp) (Supplementary Table S1). Finally, the four complete genomes were evaluated by Qualimap v.2.2.1 using the corresponding paired-end reads. The most obvious difference was that the cp DNA extraction methods, including HSLp and SucDNase, produced higher rates of mapping and mean coverage than the total DNA extraction method (Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, HSLp (high-salt low-pH) method had the highest rate of mapping (74.05% and 92.36%), and it was more effective than SucDNase in isolating cp DNA from other DNA (nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA) (Supplementary Table S2). Although its mapping rate was the lowest (3.99), the extraction method of total DNA (A. cepa) also obtained sufficient sequencing depth (334.02X) and a better assembly result because of a large number of reads and a very small cp genome (Supplementary Table S2). The four new complete cp genome sequences were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: MK335927, MK335929, MK335928 and MK335926).

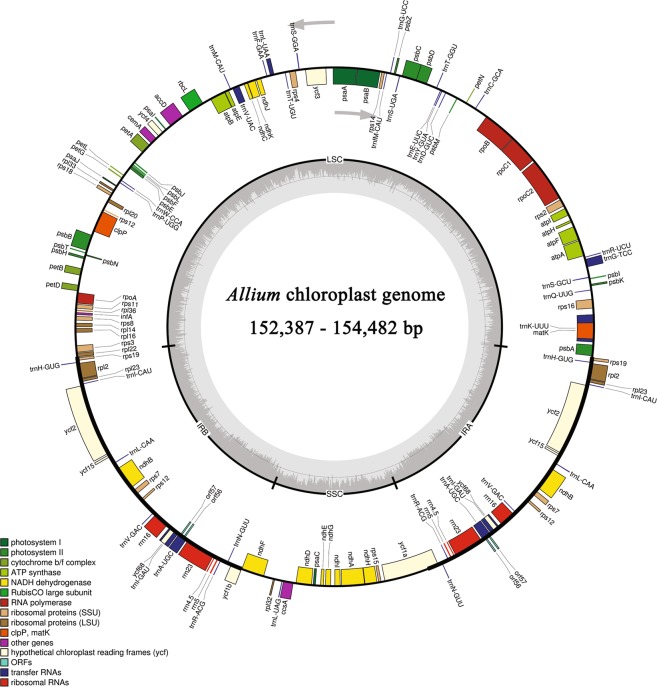

Organization and gene content of nine Allium species

The nine complete cp genome sequences, which consisted of the four Allium species sequenced in this study and five accessions from GenBank, were combined for comprehensive analysis. The genomes ranged in size from 152,387 bp (A. obliquum) to 154,482 (A. prattii) (Fig. 1). All of these genomes presented typically quadripartite structures, with two IRs (26,370–26,564) separated by the LSC (81,588–83,392) and SSC (17,853–18,066) regions (Table 1). Allium cp genomes showed similar gene content and order, containing 140–141 genes consisting of 88–89 protein-coding genes, 37–38 tRNA genes, 5–10 pseudogene and 8 rRNA genes located in the IR regions (Fig. 1; Table 1). Main components and their proportions were high conserved in eight Allium cp genomes except for A. prattii (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). However, the numbers and components of pseudogene differed substantially (Table 1; Supplementary Table S5), including those of atpB, ψinfA, rps16, rps2, rbcL, trnL-UAA and ycf2. The genes of atpB, rbcL, trnL-UAA and ycf2 were pseudogenes only in A. prattii. The pseudogene infA was absent in A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng.. The rps16 gene was a pseudogene in A. obliquum and A. sativum but a protein-coding gene in the other seven cp genomes. The rps2 gene was a pseudogene in seven accessions (A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. sativum, A. cepa N, A. cepa CMS-T, A. cepa CMS-S, and A. obliquum) but was a protein-coding gene in A. prattii and A. victorialis. One tRNA (trnL-UAA) was converted to a pseudogene because of the lack of a 5′ end in only A. prattii.

Figure 1.

Gene map of the nine Allium chloroplast genomes. The genes inside and outside the circle are transcribed in the clockwise and counter-clockwise directions, respectively. Genes belonging to different functional groups are colour coded. The thick lines indicate the extent of the inverted repeats (IRa and IRb) that separate the genomes into large single-copy (LSC) and small single-copy (SSC) regions. Grey bars on the inside of circle indicate GC content, with the line representing 50%.

Table 1.

Summary of complete cp genomes of Allium species.

| Species | Genome size | LSC | IR | SSC | Number of genes | Pseudogene | Protein coding gene | tRNA | rRNA | Accession number in Genbank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. fistulosum | 153,162 | 82,235 | 26,510 | 17,907 | 141 | 6 | 89 | 38 | 8 | MK335927 |

| A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. | 154,056 | 83,068 | 26,515 | 17,958 | 140 | 5 | 89 | 38 | 8 | MK335929 |

| A. sativum | 153,189 | 82,012 | 26,564 | 18,049 | 141 | 7 | 88 | 38 | 8 | MK335928 |

| A. cepa N | 153,586 | 82,719 | 26,468 | 17,931 | 141 | 6 | 89 | 38 | 8 | MK335926 |

| A. cepa CMS-T | 153,568 | 82,702 | 26,468 | 17,930 | 141 | 6 | 89 | 38 | 8 | KM088015 |

| A. cepa CMS-S | 153,440 | 82,543 | 26,485 | 17,927 | 141 | 6 | 89 | 38 | 8 | KM088014 |

| A. obliquum | 152,387 | 81,588 | 26,370 | 18,059 | 141 | 7 | 88 | 38 | 8 | NC_037199 |

| A. prattii | 154,482 | 83,392 | 26,513 | 18,066 | 141 | 10 | 86 | 37 | 8 | NC_037432 |

| A. victorialis | 154,074 | 83,165 | 26,528 | 17,853 | 141 | 5 | 90 | 38 | 8 | NC_037240 |

The overall GC content of different regions or components, including complete cp genome, LSC, IR, SSC, coding sequences (CDSs), tRNA, rRNA and pseudogene, was determined based on their annotation. Except for the pseudogene category, the GC content of nine complete cp genomes was very similar in each category (Supplementary Table S6). However, the GC content in eight regions or components of each genome exhibited distinct differences (Supplementary Table S6). The highest was observed in rRNA and the lowest in SSC. The order of the GC content was as follows: rRNA (>55%), tRNA (>52%), IR (>42%), CDSs (>37%), complete genome (>36%), LSC (>34%), SSC (>29%) (Supplementary Table S6). In the pseudogene category, there were relatively large differences among nine Allium taxa due to the components and numbers of pseudogenes (ψinfA, ψrps16, ψatpB, ψrps2, ψrbcL, ψtrnL-UAA, ψycf2) (Supplementary Tables S5 and S7). A. victorialis exhibited the highest GC content of 41.04%; A. sativum the lowest GC content of 35.90%; and three A. cepa types (N, CMS-T and CMS-S) and A. fistulosum showed similar GC levels (~39%) (Supplementary Table S6).

IR/SC boundary

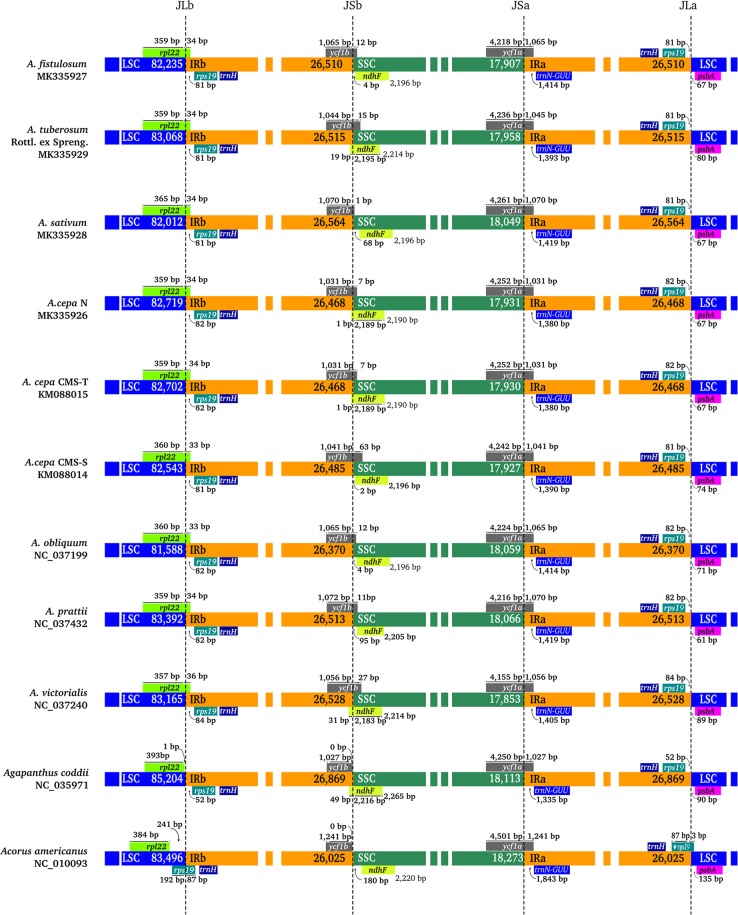

The IR/SC boundary regions of the 11 complete cp genomes were compared, and the IR/SC junctions showed substantial differences (Fig. 2). From basal monocots of Acorus americanus to Agapanthus or Allium, the expansion of the IRs to rps19 or rpl22, which was described using PCR sequences by Wang43, was also observed at the IR/ LSC junctions. In Acorus americanus, rps19 flanked the junction between LSC and IRb (JLb), while a partial sequence of rps19 was present in the IR regions and another located in the LSC region. However, two IRs all contained a complete trnH-rps19 cluster with a length of 81–84 bp away from the IR/LSC boundary in Allium and 52 bp in Agapanthus coddii. Then, JLb expanded into the 5′ portion of the rpl22 gene with a length of 33–36 bp in Allium. The junctions of IR/SSC were located in the gene ycf1(a or b) or between ycf1b and ndhF. The 3′ end of the gene ycf1b and ndhF exhibited substantial differences for expansion or contraction of IRs. Overlaps of orf (ycf1a and ndhF) were observed in A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. cepa (N, CMS-T and CMS-S), A. obliquum, A. victorialis and Agapanthus coddii. The length from ndhF to the junction between SSC and IRb (JSb) exhibited a distinct difference (from 180 to −31), so the boundary characteristics of IR/SSC were more complex than those of IR/LSC. Overall, the IR/SC boundary regions in the nine Allium species showed similar characteristics, with only slight differences in the length flanking or away from the boundary in the organization genes, namely, rpl22, rps19, ycf1b, ndhF, ycf1a and psbA.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the LSC, IR, and SSC boundary regions among the 11 chloroplast genomes. JLa, junction between LSC and IRa; JLb, junction between LSC and IRb; JSa, junction between SSC and IRa; JSb, junction between SSC and IRb. The numbers above the gene features indicate the distances from the end of the gene to the boundary sites. These features are not to scale.

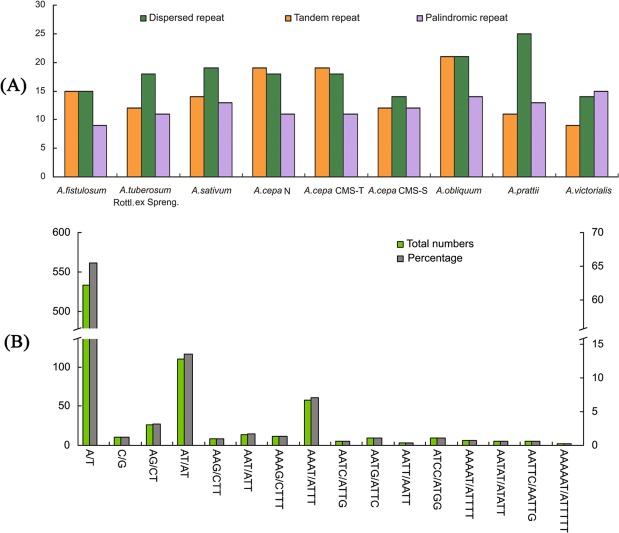

Repeat sequence analysis

The numbers and distributions of three repeat types (tandem, dispersed and palindromic repeats) in the nine Allium cp genomes were similar and conserved (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S8). There were 394 repeats, including 131 tandem repeats, 154 dispersed repeats and 109 palindromic repeats (Supplementary Table S8). These repeats were distributed in 657 sites containing 131 tandem repeat sites and 526 dispersed and palindromic repeat sites (one site was counted in one tandem repeat and two sites in one dispersed or palindromic repeat) (Supplementary Datasets 1 and 2). The lengths of the repeat units ranged from 11 to 91 bp. Based on the quadripartite structure of the cp genome, LSC regions had the most repeat sites (411, 62.56%), followed by IR (198, 30.14%), SSC (42, 6.39%) and the overhanging junction (6, 0.91%, 1 SSC/IRa and 5 IRb/SSC) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). According to the classification of gene structure, CDS, IGS (intergenic spacer) and intron, a majority of the repeat sites were in IGS regions (451, 68.65%), in which the ycf2~trnI contained the most numbers of repeat sites (2 × 27, 2 × 4.11%), and a minority were in introns (36, 5.48%) (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Only a few types of gene (e.g., psaA, psaB, rpoC2, trnF, ycf1a, ycf1b, ycf1b-ndhF, ycf2) possessed repeat elements, and the gene ycf2 contained the highest number of repeat sites (120, 18.26%). A. obliquum, with 55 repeats, had the maximum number of repeats, and A. victorialis and A. cepa CMS-S, with 37 repeats, had the lowest number of repeats (Supplementary Tables S8).

Figure 3.

Numbers of the three repeat types in the nine Allium cp genomes (A) and types and numbers of SSRs (B).

We detected 814 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the nine cp genomes using the Perl script MISA. The numbers of SSRs differ among the nine Allium genomes and vary from 73 in A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. to 96 in A. cepa N and T, as shown in Supplementary Table S9. The most abundant SSR motifs were mononucleotide repeats, which accounted for approximately 66.71% of the total SSRs, followed by dinucleotide (16.71%) and tetranucleotide (11.67%) repeats. We also found that there were more tetranucleotide repeats than trinucleotide and pentanucleotide repeats. Hexanucleotide repeats were very rare across these cp genomes, appearing only once in A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. and A. cepa CMS-S. Almost all mononucleotide repeats were composed of A/T (98.16%), with only 1.84% composed of C/G. AT/AT repeats constitute was 80.88% of dinucleotide repeats, while AG/CT repeats constitute only 19.12% (Fig. 3B).

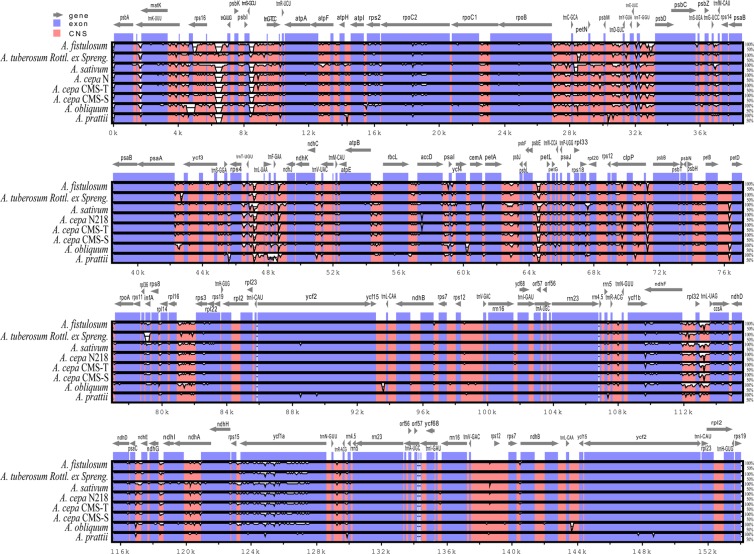

Sequence divergence analysis

With A. victorialis as a reference, alignments of the nine complete cp genomes were performed using mVISTA. The results revealed high sequence conservation (97.14–98.22%) across the nine Allium cp genomes, especially in gene regions (99.23–99.46%) (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S10). There were only slight differences in CNGs (conserved non-gene sequences) (93.88–96.62%) (Supplementary Table S10).

Figure 4.

Sequence identity plot for the nine Allium chloroplast genomes with A. victorialis as a reference, as visualized by mVISTA. Grey arrows above the alignment indicate the orientations of the genes. Blue bars represent exons, and pink bars represent non-coding sequences (CNSs). A cut-off of 50% identity was used for the plots. The Y-axis represents the percent identity within 50–100%.

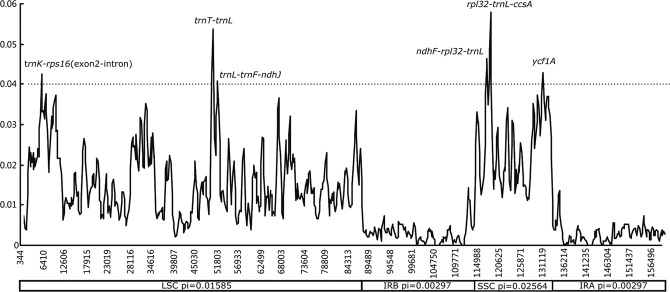

The nucleotide diversity in the complete cp genome, LSC, IR, and SSC was compared among the nine Allium cp genomes. Based on analysis by DnaSP version 6.1 software, polymorphic sites, parsimony-informative sites, and nucleotide diversity were determined. In the complete cp genomes, 5,552 polymorphic sites (3.49%) and 2,502 parsimony-informative sites (1.57%) were observed, and the nucleotide diversity was 0.01244 (Table 2). SSC regions exhibited higher divergence (0.02564) than LSC (0.01585) and IR (0.00297) regions (Table 2). To further calculate the sequence divergence level in the local regions of cp genomes, the nucleotide diversity (pi) value within a 600-bp window was calculated with 200-bp steps. These values varied from 0 to 0.05787. Then, six highly divergence regions (or hotspot regions) (Table 3), namely, trnK-rps16 (exon2-intron), trnT-trnL, trnL-trnF-ndhJ, ndhF-rpl32 -trnL, rpl32-trnL-ccsA, and ycf1a, were identified with a cut-off of 0.04. These hotspots were all located in SC (LSC and SSC) regions (Fig. 5), and only ycf1a was in the coding region. The rpl32-trnL region exhibited the highest variability (0.05787).

Table 2.

Variable site analyses in Allium cp genomes. ccpg, complete chloroplast genome.

| Region | Total number of sites | Polymorphic sites | Parsimony informative sites | Nucleotide diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccpg | 159,150 | 5,552 | 2,502 | 0.01244 |

| LSC | 87,217 | 3,732 | 1,679 | 0.01585 |

| IR | 26,652 | 238 | 114 | 0.00297 |

| SSC | 18,703 | 1,338 | 590 | 0.02564 |

| SC | 105,861 | 5,076 | 2,270 | 0.01764 |

Table 3.

Six regions of highly variable sequence of Allium. e2, exon2. i, intron.

| High variable region | Length | Polymorphic sites | Parsimony informative sites | Nucleotide diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trnK-rps16(e2-i) | 1,379 | 71 | 37 | 0.04245 |

| trnT-trnL | 1,425 | 114 | 36 | 0.04354 |

| trnL-trnF-ndhJ | 1,368 | 91 | 18 | 0.04097 |

| ndhF-rpl32-trnL | 1,614 | 153 | 67 | 0.04319 |

| rpl32-trnL-ccsA | 731 | 65 | 35 | 0.04088 |

| ycf1a | 624 | 77 | 36 | 0.04296 |

| Combine | 7,141 | 571 | 229 | 0.04253 |

Figure 5.

Sliding window analysis of the nine Allium chloroplast genome sequences (window length: 600 bp; step size: 200 bp). The Y-axis represents the nucleotide diversity of each window, while the X-axis represents the position of the midpoint.

The p-distance and number of nucleotide substitutions were used to estimate divergence among the nine Allium cp genomes. The p-distance ranged from 0.00006 to 0.02306 with an overall average of 0.01244, and the number of nucleotide substitutions was found to range from 9 to 3,411 (Supplementary Table S11). A. prattii and A. sativum exhibited the greatest sequence divergence (0.02306). A. cepa N exhibited only nine nucleotide substitutions compared to A. cepa CMS-T but 316 nucleotide substitutions compared to A. cepa CMS-S. These results further indicated that the onion species with N and CMS-T cytoplasm were more closely related to each other than to that with a CMS-S cytoplasm.

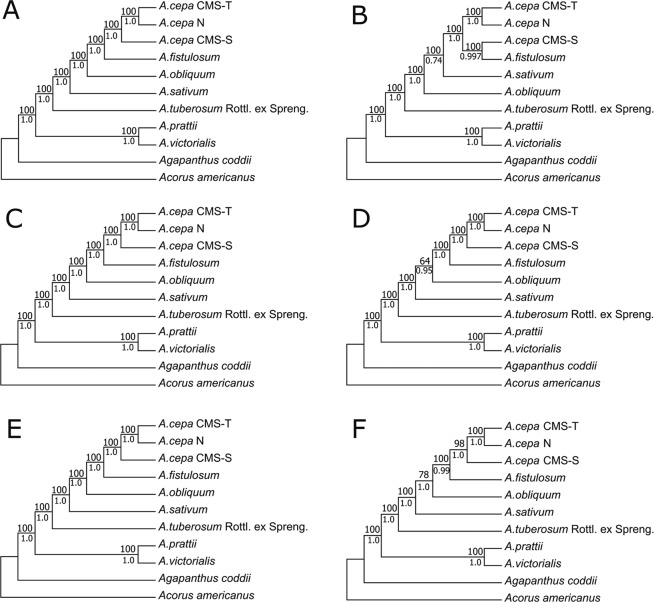

Phylogenetic analysis

In this study, six datasets (complete chloroplast genome, IR, LSC, SSC, SC and the combined variable regions) from 11 cp genomes sequences were created on the basis of their annotation, and the number of sites used to construct phylogenetic trees ranged from 3,724 to 137,185 (Supplementary Table S12). According to the identification results obtained by jModeltest v2.1.10, the best-fit models for each dataset based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) are listed in Supplementary Table S12. The maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) models were selected based on the above results and the RAxML v8.2.12 manual. The topologies of the phylogenetic trees based on the two methods of analysis (ML and BI) were identical for each dataset. And the datasets generated similar topological structures with a very high support, except for the IR dataset (Fig. 6). Allium species and Agapanthus coddii produced two distinct branches with very high support (100% and 1.00). In the genus Allium, nine accessions were divided into two sister clades. The first clade contained two species, namely, A. prattii and A. victorialis. The 2nd clade included seven accessions, in which A. cepa (CMS-T and N) was grouped in a sister branch and then clustered step by step with A. cepa CMS-S, A. fistulosum, A. obliquum, A. sativum and A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationships of the nine Allium species inferred by maximum likelihood (ML) methods and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses of different datasets. (A) Complete chloroplast genome. (B) IR region. (C) LSC region. (D) SSC region. (E) SC region. (F) Six divergence hotspots. The numbers associated with each node are bootstrap support values (above the node) for ML and posterior probability values (under the node) for BI in (A–F).

From the dataset of the divergence hotspots (including only 229 parsimony-informative sites) (Table 3), we also inferred the phylogenetic relationships that were identical to other datasets except for IR dataset, in terms of topological structure (Fig. 6). Moreover, even in the infraspecific classification, three cytoplasmic types of A. cepa were also clearly identified. The cp genome can be used to resolve the deeper branches within species. However, the present study analysed only a limited number of species. With the rapid improvement of sequencing technologies, the sequencing of complete cp genome will become routine. Therefore, more and more complete sequences of cp genome will be used to further elucidate the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Allium.

Discussion

In this study, four complete cp genome sequences were sequenced and assembled. The genome sizes ranged from 153,162 bp (A. fistulosum) to 154,056 bp (A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng.), similar to the genome size for A. cepa reported by Kohn42 and Kim44. Subsequently, nine complete Allium cp genome sequences, including those of the four Allium species sequenced in this study and five obtained from GenBank, were compared. The cp genomes of Allium are highly conserved, with identical gene content and order, and genomic structures comprising four parts33. The GC levels of the complete cp genomes were very similar, ranging from 36.7 to 37.0% (Supplementary Table S6), which has also been observed in other angiosperm cp genomes42,44,45. Additionally, the rps12 gene is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′ end in the IR region, as has been identified previously in other reports42. However, the numbers and components of pseudogene were substantially different, especially the loss of sequence infA in A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng.. In addition, surprisingly, the genes atpB, rbcL, trnL-UAA and ycf2 were present as pseudogene in only A. prattii but as protein-coding genes in the other eight cp genomes (Supplementary Table S5). This transformation might be caused by sequence contamination originating from the mitochondrial genome46,47 or by annotation error, as previously discussed for Fagaceae48. Due to the components and numbers of pseudogene, the GC levels and lengths of the pseudogene also varied by species from 35.9% to 41.04% and 1,043 to 17,782, respectively (Supplementary Table S7).

The change in position of the IR/SC junction may have been caused by contraction or expansion of the IR region, which is a common evolutionary phenomenon34,43,49–51 and may cause variations in the lengths of angiosperm plastid genomes49. In the nine Allium species, the IR/SC boundary regions showed similar characteristics, with only slight differences observed in the length flanking or away from organization genes, namely, rpl22, rps19, ycf1b, ndhF, ycf1a and psbA (Fig. 2). Expansion of IR regions was also found from basal monocots of Acorus americanus to Agapanthus or Allium43. The complete trnH-rps19 cluster is present in IR regions, in which this type of IR/LSC junction is consistent with TYPE III, as reported by Wang43. We also found that A. cepa N and CMS-T exhibited the same features in four junctions, but A. cepa CMS-S exhibited slight differences compared with A. cepa N and CMS-T. For example, the length of extension of rpl22 into IRb was 34 bp in N and CMS-T and 33 bp in CMS-S. These differences in length were also exhibited by other organization genes, such as rps19, ycf1b, ycf1a, ndhF and psbA. These results maybe hint the difference in origin and evolution by previous reports44,52–56.

Large, complex repeat sequences may play important roles in the rearrangement of plastid genomes and sequence divergence57,58. We found that the repeat sites in the nine Allium species were similar and conserved, usually located in IGS regions (451, 68.65%) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Surprisingly, the ycf2 gene contained the most repeat sites (120, 18.26%), and the ycf1 gene contained only seven sites (1.07%) (Figs S2 and S3). Moreover, we identified 81 long repeats of more than 40 bp, accounting for approximately 20.56% of the total 394 repeats. This rate is similar to previous reports on other plant lineages34,59,60. SSRs are thought to be the results of slipped strand mispairing during DNA replication, which are frequently observed in cp genomes and have been shown to have substantial application potential in population genetics and breeding programmes61–63. In this study, 814 SSRs were identified, with the most abundant mononucleotide repeats, accounting for 66.71% of the total SSRs, followed by dinucleotide, tetranucleotide, trinucleotide, pentanucleotide, and hexanucleotide repeats. Almost all mononucleotide repeats were composed of A/T (98.16%), with only 1.84% composed of C/G. Among dinucleotide repeats, AT/AT accounted for 80.88%, while AG/CT for only 19.12%. Our results are comparable to previously reported findings that SSRs in cp genomes are composed of polyadenine (poly A) or polythymine (poly T) repeats and rarely contained tandem guanine (G) or cytosine (C) repeats45. We also found that tetranucleotide repeats were more abundant than trinucleotide and pentanucleotide repeats, which is consistent with a report on Quercus species64. Hexanucleotide repeats were very rare across the nine Allium cp genomes, similar to the results in Lilium45. These new SSR resources will potentially be useful for population studies on the Allium genus, especially in combination with other informative nuclear genome SSRs.

The alignments of the nine Allium complete cp genomes revealed a high degree of synteny (Fig. 4). SC regions were more divergent than two IR regions, and the non-coding regions exhibited greater divergence than the coding regions. Similar results are reported previously for many cp genomes31,39,45,64. Differences in accD in S/N-cytoplasmic onions, which were detected in a previous report42, were also observed (Fig. 4). The nucleotide substitution rate is a central feature of molecular evolution65. All pair-wise sequence comparisons in our study showed that the number of nucleotide substitutions differed greatly, ranging from 9 to 3,411 (Supplementary Table S11). This result suggests that DNA sequences evolve at different rates in different species which had also been observed in other taxa66.

Six highly divergence regions (Table 3), namely, trnK-rps16 (exon2-intron), trnT-trnL, trnL-trnF-ndhJ, ndhF-rpl32-trnL, rpl32-trnL-ccsA, and ycf1a, were identified with a cut-off of 0.04. These regions exhibited far greater nucleotide diversity than matK and rps16 previously reported in evolutionary issues and taxonomic relationships1,2,11,12,14–21. Based on these results, we believe that these regions, which exhibit relatively high sequence deviation, might be regarded as potential molecular markers and are useful resources for interspecies and infraspecific phylogenetic analysis of Allium species.

The phylogenetic trees based on different datasets produced similar topological structures, except for the IR dataset, possibly because this region was highly conserved and provided fewer informative sites than the SC regions (Table 2). First, Allium species and Agapanthus coddii produced two distinct branches with very high support (100% and 1.00). Then, in the genus Allium, nine taxa were divided into two clades. The first clade included two species (A. prattii and A. victorialis) belonging to the second evolutionary line described in previous reports2,11,22. The other species, including A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. sativum, A. obliquum, and A. cepa (CMS-T, CMS-S and N), grouped into clade two, belonging to the third evolutionary line2,11,22. In A. cepa, CMS-T and N grouped into a sister branch and then clustered with CMS-S. These results indicate that CMS-T and N share a close relationship and that CMS-S does not originate from A. cepa N and T, which is consistent with previous reports that the S cytoplasm had two origins67. The S cytoplasm may be an alien cytoplasm transferred from an unknown Allium species to the bulb onion through the viviparous interspecific triploid ‘Pran′. Alternatively, the S cytoplasm could be a component of one or more wild populations from which onion was domesticated, and S-cytoplasmic plants could be the seed parents of ‘Pran’67.

The results presented here not only robustly support previous reports of three major clades inferred by ITS, rps16 and matK data1,2,11,12,14–21 but also show increased bootstrap or posterior probability values, especially at low taxonomic levels (such as infraspecific classification). These results also suggest that cp genome data can effectively resolve the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Allium. Although the matK, rps16, and ITS genes have been widely used to investigate taxonomy in Allium, these markers will exhibit increasingly extremely low discriminatory power because this genus contains more than a lot of species and especially a large number of new Allium species are being identified step by step11,21. Fortunately, for the purposes of this study, the cp genomes of Allium species have highly divergent regions with far greater nucleotide diversity than matK and rps16. Moreover, using the dataset of highly divergent regions, we also inferred the deeper phylogenetic relationships that were identical with other datasets, except for the IR dataset. This finding also suggests that these regions are useful resources for the phylogenetic analysis of Allium species, not only in interspecies but also infraspecific classification. Although the present study analyzed a limited number of species, our data will serve as a reference for future genome-scale phylogenetic studies of Allium. With the rapid improvement in sequencing technologies, sequencing of complete cp genome will become routine. Therefore, an increasing number of cp genome sequences will be used to further elucidate the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Allium.

Methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Fresh leaves of four Allium species were harvested from the Vegetable and Flower Research Institute of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences. DNA samples were isolated by three methods (Supplementary Table S1): (1) Total genomic DNA for A. cepa N (N218) was isolated using the Plant Genome Extraction Kit (PGEK) (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China); (2) cpDNA for A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. was isolated by the sucrose-DNase (SucDNase) method68; (3) cpDNA for A. fistulosum and A. sativum was isolated by the high-salt low-pH (HSLp) method69. DNA concentration and quality were measured using a NanoPhotometer P330 (Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany) and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

DNA samples from A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. and A. sativum were sheared to construct a ~350-bp paired-end library in accordance with the Illumina HiSeq 4000 protocol to obtain an average read length of 150 bp (Supplementary Table S1). Another ~350-bp paired-end library for the A. cepa sample was constructed using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 protocol with an average read length of 100 bp (Supplementary Table S1). Quality control of the raw sequence reads was performed using an ultra-fast FASTQ preprocessor, fastp version 0.15.070, using default parameters, except -q 20 and -n 10. Each species yielded at least 1.2 Gb of clean data (Supplementary Table S2).

First, high-quality reads were assembled by NOVOPlasty 2.6.271 with the default parameters set using the seed sequence AcrbcL from the reference sequence NC_024813.1. The orientation was resolved manually based on NC_024813.1. A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng. was not circularized by NOVOPlasty, and therefore, we assembled this sequence using SPAdes 3.11.172. The file of “fastg” was visualized by the software Bandage 0.8.173, and the alignment of nodes or contigs were conducted by Mummer 3.2374. Gaps in the cp genome sequences were filled by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing based on reference NC_024813.1. PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl using the TaKaRa PCR Amplification Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). The PCR mixtures contained 50 ng template DNA, 0.2 μM of each primer, and 12.5 μl PCR Mix. The primer pairs p1 (5′ GAGACTACCAGATCCCCGCTAT 3′) and p2 (5′ CTTTGGAATACTGGAAGGGTCG 3′) were used to amplify gap1, and p3 (5′ ATGTCGAATACTAACTTATCTGTCTGC 3′) and p4 (5′ ATTTCACCATAGCGGCTTACTT 3′) to gap2. The PCR protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, with a final 5 min extension at 72 °C. The amplified products were separated on 1.0% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Evaluation of the assembly was performed by Qualimap v.2.2.175.

The complete cp genomes were annotated by plann v.1.1.276 using NC_024813.1 as a reference and then checked by DOGMA77 (http://dogma.ccbb.utexas.edu/). The positions of start and stop codons, and the boundaries between introns and exons were manually corrected by comparison with the published cp genome of NC_024813.1. The annotated GenBank files were used to draw circular cp genome maps using OrganellarGenome DRAW (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/OGDraw.html). The organization and gene content of the nine Allium taxa were analysed according to the corresponding annotations. Then, the boundary regions of the LSC, SSC, and IRs were also compared from 11 accessions, including the nine Allium cp genomes and those of the closely related species Agapanthus coddii, and the basal monocot Acorus americanus.

Repeat element analysis

Tandem repeats were detected using Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) version 4.0978 with advanced parameters. The alignment parameters match, mismatch, and indel were set to 2, 7, and 7, respectively, and the minimum alignment score and maximum period size were set to 80 and 500, respectively. Other parameters were set to default values. The Perl script repfind.pl from Vmatch79 was used to find dispersed and palindromic repeats in which the minimal repeat size was 30 bp and the two repeat copies had at least 90% similarity (i.e., a Hamming distance of 3, -h 3). Then, two types of repeats were sorted by Vmatch with the -d (or -p, separately) -l 30 -h 3 -sort ia options. Complete IRa and IRb were excluded from the palindromic repeats. The Perl script MISA80 was used to detect SSRs or microsatellites. The minimum numbers of repeats were 10, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats, respectively.

Sequence divergence analysis

The complete cp genomes were compared using the mVISTA program81 with A. victorialis as a reference, because of the least numbers of pseudogenes and the second length cp genome. Then, the sequences were first aligned using MAFFT v7.39482 and manually adjusted in MEGA v7.0.2683. Subsequently, a sliding window analysis was conducted to evaluate the nucleotide variability (Pi) of the cp genome using DnaSP v6.12.01 software84. The step size was set to 200 bp, and the window length was set to 600 bp. Variable and parsimony-informative base sites across the complete cp genomes and the LSC, SSC, and IR regions of the nine cp genomes were calculated. The p-distance and number of nucleotide substitutions among Allium cp genomes were calculated using MEGA v7.0.2683 software.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted on the basis of 11 accessions, including the four species in the current study, five other Allium species (A. obliquum, A. prattii, A. victorialis, A. cepa CMS-T and A. cepa CMS-S), and Agapanthus coddii, belonging to the genus Agapanthus, which is closely related to Allium. Acorus americanus was used as an out-group. Because molecular evolutionary rates differed among the different cp genome regions, six datasets were created according to the complete cp genome annotation described above, consisting of (A) complete chloroplast genome, (B) IR region, (C) LSC region, (D) SSC region, (E) SC region and (F) the combined variable regions. All sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.39482, and all alignments were manually adjusted in MEGA7.0.2683. All gap positions were eliminated by Gblocks v0.91b85. All phylogenetic analyses were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) methods and Bayesian inference (BI). The best-fit substitution models were selected by the AIC for ML trees and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for BI trees in jModeltest v2.1.1086,87. ML analysis was performed using RAxML v8.2.12 with 1,000 rapid bootstrap replicates88. BI was implemented with MrBayes v3.2.689. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run, each with three heated and one cold chain for 10 million generations (Ngen = 10,000,000). All trees were sampled every 1,000 generations (Samplefreq = 1,000). Stationarity was considered to be reached when the average standard deviations of the split frequencies remained below 0.01. The first 25% of the trees were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to build a majority-rule consensus tree.

Accession code

The four complete cp genome sequences of Allium species (A. fistulosum, A. tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng., A. sativum and A. cepa), were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: MK335927, MK335929, MK335928 and MK335926).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1-S12 and Figure S1-S3

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 31672165, 31201635), the Young Talents Training Program of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (IVFSAAS2016-2018-01), the Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province, China (2016~2020) and China Agriculture Research System (CARS-24-A-10).

Author Contributions

Y.M.H. and X.W. conceived the experiments; L.M.G., S.P.K. and Y.Y.Y. collected the samples; Y.M.H., Y.Q.S. and Y.H.Y. conducted the experiments; Y.M.H., L.M.G. and B.J.L. analyzed the results; Y.M.H. and L.M.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48708-x.

References

- 1.Fritsch RM, Blattner FR, Gurushidze M. New classification of Allium L. subg. Melanocrommyum (Webb & Berthel) Rouy (Alliaceae) based on molecular and morphological characters. Phyton. 2010;49:145–220. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li QQ, et al. Phylogeny and biogeography of Allium (Amaryllidaceae: Allieae) based on nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and chloroplast rps16 sequences, focusing on the inclusion of species endemic to China. Ann. Bot. 2010;106:709–733. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler EJ, Mashayekhi S, McNeal DW, Columbus JT, Pires JC. Molecular systematics of Allium subgenus Amerallium (Amaryllidaceae) in North America. Am. J. Bot. 2013;100:701–711. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deniz İG, Genç İ, Sarı D. Morphological and molecular data reveal a new species of Allium (Amaryllidaceae) from SW Anatolia, Turkey. Phytotaxa. 2015;212:283–292. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.212.4.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havey MJ. Phylogenetic relationships among cultivated Allium species from restriction enzyme analysis of the chloroplast genome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1991;81:752–757. doi: 10.1007/bf00224985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1998;85:531–553. doi: 10.2307/2992015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2003;141:399–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chase MW, Reveal JL, Fay MF. A subfamilial classification for the expanded asparagalean families Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae and Xanthorrhoeaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009;161:132–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00999.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009;161:105–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friesen N, Fritsch RM, Blattner FR. Phylogeny and new intrageneric classification of Allium (Alliaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS sequences. Aliso. 2006;22:372–395. doi: 10.5642/aliso.20062201.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abugalieva S, et al. Taxonomic assessment of Allium species from Kazakhstan based on ITS and matK markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:258. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1194-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Berg GL, Samoylov A, Klaas M, Hanelt P. Chloroplast DNA restriction analysis and the infrageneric grouping of Allium (Alliaceae) Plant Syst. Evol. 1996;200:253–261. doi: 10.1007/bf00984939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubouzet JG, Shinoda K. Relationships among Old and New World Alliums according to ITS DNA sequence analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999;98:422–433. doi: 10.1007/s001220051088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mes TH, Fritsch RM, Pollner S, Bachmann K. Evolution of the chloroplast genome and polymorphic ITS regions in Allium subg. Melanocrommyum. Genome. 1999;42:237–247. doi: 10.1139/g98-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurushidze M, Fritsch RM, Blattner FR. Phylogenetic analysis of Allium subg. Melanocrommyum infers cryptic species and demands a new sectional classification. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;49:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurushidze M, Mashayekhi S, Blattner FR, Friesen N, Fritsch RM. Phylogenetic relationships of wild and cultivated species of Allium section Cepa inferred by nuclear rDNA ITS sequence analysis. Plant Syst. Evol. 2007;269:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s00606-007-0596-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryzhova NN, Kholda OA, Kochieva EZ. Structural characteristics of the chloroplast rpS16 intron in Allium sativum and related Allium species. Mol. Biol. 2009;43:766. doi: 10.1134/s0026893309050082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirschegger P, Jaške J, Trontelj P, Bohanec B. Origins of Allium ampeloprasum horticultural groups and a molecular phylogeny of the section Allium (Allium; Alliaceae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010;54:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herden T, Hanelt P, Friesen N. Phylogeny of Allium L. subgenus Anguinum (G. Don. ex W.D.J. Koch) N. Friesen (Amaryllidaceae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;95:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li QQ, Zhou SD, Huang DQ, He XJ, Wei XQ. Molecular phylogeny, divergence time estimates and historical biogeography within one of the world’s largest monocot genera. AoB Plants. 2016;8:plw041. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plw041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen NH, Driscoll HE, Specht CD. A molecular phylogeny of the wild onions (Allium; Alliaceae) with a focus on the western North American center of diversity. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;47:1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H, Davis A, Cota-Sánchez J. Comparative floral structure of four new world Allium (Amaryllidaceae) species. Systematic Botany. 2011;36:870–882. doi: 10.1600/036364411X604895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe CJ, et al. Evolution of the chloroplast genome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2003;358:99–107. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raven JA, Allen JF. Genomics and chloroplast evolution: what did cyanobacteria do for plants? Genome Biol. 2003;4:209–209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho KS, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) and comparative analysis with common buckwheat (F. esculentum) Plos One. 2015;10:e0125332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birky CW. Uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes: mechanisms and evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11331–11338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song, Y. et al. Development of chloroplast genomic resources for Oryza species discrimination. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 10.3389/fpls.2017.01854 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011;76:273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wambugu PW, Brozynska M, Furtado A, Waters DL, Henry RJ. Relationships of wild and domesticated rices (Oryza AA genome species) based upon whole chloroplast genome sequences. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13957. doi: 10.1038/srep13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asaf, S. et al. Complete chloroplast genome of Nicotiana otophora and its comparison with related species. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.00843 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Dong W, Xu C, Cheng T, Zhou S. Complete chloroplast genome of Sedum sarmentosum and chloroplast genome evolution in Saxifragales. Plos One. 2013;8:e77965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolodner R, Tewari KK. Inverted repeats in chloroplast DNA from higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:41–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang H, Shi C, Liu Y, Mao S-Y, Gao L-Z. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaney L, Mangelson R, Ramaraj T, Jellen EN, Maughan PJ. The complete chloroplast genome sequences for four Amaranthus species (Amaranthaceae) Appl. Plant Sci. 2016;4:1600063. doi: 10.3732/apps.1600063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi KS, Chung MG, Park S. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of three Veroniceae species (Plantaginaceae): comparative analysis and highly divergent regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:355. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu, H. et al. Species delimitation and interspecific relationships of the genus Orychophragmus (brassicaceae) inferred from whole chloroplast genomes. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.01826 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Krak K, et al. Allopolyploid origin of Chenopodium album s. str. (Chenopodiaceae): a molecular and cytogenetic insight. Plos One. 2016;11:e0161063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong, S. Y. et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences and comparative analysis of Chenopodium quinoa and C. album. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 10.3389/fpls.2017.01696 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Dong W, Liu J, Yu J, Wang L, Zhou S. Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin W, Deusch O, Stawski N, Grunheit N, Goremykin V. Chloroplast genome phylogenetics: why we need independent approaches to plant molecular evolution. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohn CV, Kiełkowska A, Havey MJ. Sequencing and annotation of the chloroplast DNAs and identification of polymorphisms distinguishing normal male-fertile and male-sterile cytoplasms of onion. Genome. 2013;56:737–742. doi: 10.1139/gen-2013-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang R-J, et al. Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S, Park JY, Yang T. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences of a normal male-fertile cytoplasm and two different cytoplasms conferring cytoplasmic male sterility in onion (Allium cepa L.) J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015;90:459–468. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2015.11513210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du Y-P, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Lilium: insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic analyses. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5751. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06210-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stern D, Lonsdale D. Mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes of maize have a 12-kilobase DNA sequence in common. Nature. 1982;299:698–702. doi: 10.1038/299698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings MP, Nugent JM, Olmstead RG, Palmer JD. Phylogenetic analysis reveals five independent transfers of the chloroplast gene rbcL to the mitochondrial genome in angiosperms. Curr. Genet. 2003;43:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, Y. et al. Plastid genome comparative and phylogenetic analyses of the key genera in Fagaceae: highlighting the effect of codon composition bias in phylogenetic inference. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 10.3389/fpls.2018.00082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kim KJ, Lee HL. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 2004;11:247–261. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansen DR, et al. Phylogenetic and evolutionary implications of complete chloroplast genome sequences of four early-diverging angiosperms: Buxus (Buxaceae), Chloranthus (Chloranthaceae), Dioscorea (Dioscoreaceae), and Illicium (Schisandraceae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007;45:547–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis JI, Soreng RJ. Migration of endpoints of two genes relative to boundaries between regions of the plastid genome in the grass family (Poaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2010;97:874–892. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Courcel AG, Vedel F, Boussac JM. DNA polymorphism in Allium cepa cytoplasms and its implications concerning the origin of onions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1989;77:793–798. doi: 10.1007/BF00268328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holford P, Croft JH, Newbury HJ. Differences between, and possible origins of, the cytoplasms found in fertile and male-sterile onions (Allium cepa L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 1991;82:737–744. doi: 10.1007/BF00227319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Havey MJ. A putative donor of S-cytoplasm and its distribution among open-pollinated populations of onion. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993;86:128–134. doi: 10.1007/bf00223817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim KQ. Identification of hypervariable chloroplast intergenic sequences in onion (Allium cepa L.) and their use in analysing the origins of male-sterile onion cytotypes. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013;88:187–194. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2013.11512955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim B, Kim K, Yang T-J, Kim S. Completion of the mitochondrial genome sequence of onion (Allium cepa L.) containing the CMS-S male-sterile cytoplasm and identification of an independent event of the ccmFN gene split. Curr. Genet. 2016;62:873–885. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timme RE, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. A comparative analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) plastid genomes: identification of divergent regions and categorization of shared repeats. Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:302–312. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weng ML, Blazier JC, Govindu M, Jansen RK. Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;31:645–659. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang YJ, Ma PF, Li DZ. High-throughput sequencing of six bamboo chloroplast genomes: phylogenetic implications for temperate woody bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) Plos One. 2011;6:e20596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai J, Ma PF, Li HT, Li DZ. Complete plastid genome sequencing of four Tilia species (Malvaceae): a comparative analysis and phylogenetic implications. Plos One. 2015;10:e0142705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levinson G, Gutman GA. Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:203–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cesare MD, Hodkinson T, Barth S. Chloroplast DNA markers (cpSSRs, SNPs) for Miscanthus, Saccharum and related grasses (Panicoideae, Poaceae) Mol. Breed. 2010;26:539–544. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9451-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tong W, Kim TS, Park YJ. Rice chloroplast genome variation architecture and phylogenetic dissection in diverse Oryza species assessed by wholegenome resequencing. Rice. 2016;9:57. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of five Quercus Species. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.00959 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Gaut B, Yang L, Takuno S, Eguiarte L. The patterns and causes of variation in plant nucleotide substitution rates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011;42:245–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145119.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith SA, Donoghue MJ. Rates of molecular evolution are linked to life history in flowering plants. Science. 2008;322:86–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1163197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Havey MJ. On the origin and distribution of normal cytoplasm of onion. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1997;44:307–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1008680713032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Triboush SO, Danilenko NG, Davydenko OG. A method for isolation of chloroplast DNA and mitochondrial DNA from sunflower. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1998;16:183–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1007487806583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vieira LdN, et al. An improved protocol for intact chloroplasts and cpDNA isolation in conifers. Plos One. 2014;9:e84792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. bioRxiv, 10.1101/274100 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e18–e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3350–3352. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurtz S, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.García-Alcalde F, et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2678–2679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang DI, Cronk QCB. Plann: A command-line application for annotating plastome sequences. Appl. Plant Sci. 2015;3:1500026. doi: 10.3732/apps.1500026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kurtz, S. The Vmatch large scale analysis software - a manual, http://www.vmatch.de/virtman.pdf (2017).

- 80.Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney R, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakamura T, Yamada KD, Tomii K, Katoh K. Parallelization of MAFFT for large-scale multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2490–2492. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rozas J, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by Maximum Likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1-S12 and Figure S1-S3