Abstract

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), a widely used flame retardant, caused uterine tumors in rats. In this study, TBBPA was administered to male and female Wistar Han rats and B6C3F1/N mice by oral gavage in corn oil for 2 years at doses up to 1000 mg/kg. TBBPA induced uterine epithelial tumors including adenomas, adenocarcinomas, and malignant mixed Müllerian tumors (MMMTs). In addition, endometrial epithelial atypical hyperplasia occurred in TBBPA-treated rats. Also found to be related to TBBPA treatment, but at lower incidence and at a lower statistical significance, were testicular tumors in rats, and hepatic tumors, hemangiosarcomas (all organs) and intestinal tumors in male mice. It is hypothesized that the TBBPA uterine tumor carcinogenic mechanisms involve altered estrogen levels and/or oxidative damage. TBBPA treatment may affect hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase-17β (HSD17β) and/or sulfotransferases, enzymes involved in estrogen homeostasis. Metabolism of TBBPA may also result in formation of free radicals. The finding of TBBPA-mediated uterine cancer in rats is of concern because TBBPA exposure is widespread and endometrial tumors are a common malignancy in women. Further work is needed to understand TBBPA cancer mechanisms.

Keywords: Tetrabromobisphenol A, Uterine tumors, Malignant Mixed Müllerian tumors (MMMT), flame retardants

Introduction

The potential for toxicities after exposure to chemicals in common household products is often unknown. One area of concern is the lack of information on the carcinogenic potential of flame retardants used to meet fire safety standards in printed circuit boards where tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) is the most commonly used flame retardant (U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2013). Printed circuit boards treated with TBBPA are found in computers, televisions, and cell phones (U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2008, U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2014). It is estimated that TBBPA accounts for 59% of all brominated flame retardants used world wide (Law et al., 2006). Products with both additive and chemically bonded forms of TBBPA have been shown to release TBBPA into the environment (Birnbaum and Staskal, 2004). While exposure to TBBPA may be widespread, systematic measurement of TBBPA in human and animal tissues has not been comprehensively studied in the U. S, and TBBPA is not included as part of the chemical screening evaluations in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) program (Center for Disease Control, 2012).

The U. S. EPA designated a low hazard index for TBBPA based on the evaluation of the available toxicity data (U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2008). Furthermore, a risk assessment conducted by the European Union did not identify any health concerns in humans exposed to TBBPA (European Risk Assessment Report, 2006). TBBPA has a low level of acute toxicity, with oral LD50s in the g/kg range in rodent models (European Risk Assessment Report, 2006). Following oral exposure, TBBPA appears to have a low systemic bioavailability via rapid conjugation and elimination in the rat (Hakk et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 2014b, Kuester et al., 2007, Schauer et al., 2006). Metabolism of TBBPA may be similar in humans and rodents (Schauer et al., 2006, Zalko et al., 2006). Studies have indicated that TBBPA may perturb thyroid and estrogen homeostasis (Hamers et al., 2006, Van der Ven et al., 2008). Further, in vivo metabolism of TBBPA may include formation of reactive free radicals (Chignell et al., 2008).

To date there have been no studies to evaluate the carcinogenic potential of TBBPA. However, other National Toxicology Program (NTP) studies have shown the potential for brominated flame retardants to be multispecies carcinogens (Dunnick et al., 1997). Brominated flame retardants causing cancer in rodent model systems include 2,2-bis(bromomethyl)-1,3-propanediol (CAS# 3296-90-0); decabromodiphenyl oxide (CAS# 1163-19-5); 2,3-dibromo-1-propanol (CAS# 96-13-9); hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) (CAS#s 25637-99-4; 3194-55-6); polybrominated biphenyl mixture (Firemaster FF-1) (CAS# 67774-32-7); and tribromomethane (CAS# 75-25-2) (Dunnick et al., 1997).

Because of the lack of cancer data, and the finding that other brominated chemicals are carcinogenic, there was need for additional work to evaluate the TBBPA carcinogenic potential. The TBBPA cancer studies reported here provide information to compare the cancer hazard potential for TBBPA to that of other commonly used brominated flame-retardants. These data are important for consideration in future risk assessments of TBBPA exposure to humans.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

Tetrabromobisphenol A (Albemarle Corporation, Baton Rouge, LA) was prepared for oral gavage administration in corn oil to deliver the target concentrations of the chemical (0, 250, 500, or 1000 mg/kg) to rats in a volume of 5 mL/kg body weight and to mice at a volume of 10 mL/kg body weight. Animals were dosed 5 days per week for 13 weeks.

Doses for this 2-year study were based on results from 3-month studies, which showed no treatment-related effects on survival, clinical signs or treatment-related lesions except for kidney cytoplasmic alteration (decreased cytoplasmic vacuoles) in male mice at 500 or 1000 mg/kg. Because the 3-month study did not reveal any TBBPA effects that would compromise a 2-year study, the high dose selected for the 2-year study was 1000 mg/kg (NTP 2013).

Male and female Wistar Han rats [Crl:WI(Han)] (referred as Wistar Han rats) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC) and B6C3F1/N mice from Taconic Farms, Inc. (Germantown, NY). At the start of the study the animals were 5–6 weeks of age. The animals were housed by species and sex, two to three male rats per cage, five female rats per cage, one male mouse per cage, and five female mice per cage. Tap water and NTP-2000 diet (Zeigler Brothers, Inc. Gardners, PA) were made available ad libitum. The care of animals on this study was according to NIH procedures as described in the “The U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, available from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, RKLI, Suite 360, MSC 7982, 6705 Rockledge Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-7982 or online at http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/olaw.htm#pol”. The use of the animals was approved by the local animal care and use committee.

Necropsy and pathology

All tissue collections, necropsies, tissue processing and histopathological examinations were performed according to NTP specifications (http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/test_info/finalntp_toxcarspecsjan2011.pdf). NTP guidelines were used for all nomenclature (http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/nnl/). Histological examinations were performed by board certified anatomic veterinarian pathologists with experience reading these types of studies.

Complete necropsies were performed on all animals when moribund, when found dead, or at the end of the two-year exposure period. When possible, causes of death were attributed to all animals that were found dead. At necropsy, all organs and tissues were examined for grossly visible lesions. Tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The following tissues were examined microscopically from male and/or female animals: gross lesions and tissue masses, adrenal gland, bone with marrow, brain, cervix, clitoral gland, esophagus, eyes, gallbladder (mice only), Harderian gland, heart, large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum), small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum), kidney, liver, lungs, lymph nodes (mandibular and mesenteric), mammary gland, nose, ovary, pancreas, parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, preputial gland, prostate gland, salivary gland, skin, spleen, stomach (forestomach and glandular), testis with epididymis and seminal vesicle, thymus, thyroid gland, trachea, urinary bladder, uterus with cervix), and vagina. Following completion of the studies, histopathology diagnoses ware confirmed by NTP pathology peer reviews (Boorman and Eustis, 1986, Hardisty and Boorman, 1986)

There were reviews of the female rat reproductive tissues termed the “original transverse review” and the “residual longitudinal review.” The original review involved a transverse section through each uterine horn, approximately 0.5 cm cranial to the cervix, and an evaluation of gross cervical and vaginal lesions. The residual longitudinal review involved collection and evaluation of remaining uteri, vaginas and cervices stored in formalin and sectioned in a longitudinal manner. The weight of uterine tumor masses when observed at necropsy were taken.

Immunohistochemical staining

An indirect immunoperoxidase procedure was performed. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with Declere solution (Cell Marque; Catalog No. 921P) for 15 minutes in a pressure cooker. The slides were then rinsed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.2 + 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). Next, endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubating the slides with 3% hydrogen peroxide for ten minutes and then rinsed twice with PBST. The slides were then treated with a protein block designed to reduce nonspecific binding for 20 minutes. The protein block was prepared as follows: PBST + 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA); and 1.5% normal donkey serum. Following the protein block, the primary antibodies (detection antibody, negative control antibody, or assay control [buffer alone]) were applied to the slides and incubated for one hour at room temperature. Next, the slides were rinsed twice with PBST, and the biotinylated secondary antibody (donkey anti-mouse IgG [Jackson ImmunoResearch; Catalog No. 715-065-151) was applied to the slides for 30 minutes. Then, the slides were rinsed twice with PBST, reacted for 30 minutes with the ABC Elite reagent (Vector Laboratories; Catalog No. PK-6100), and rinsed twice with PBST. Next, DAB (Sigma-Aldrich; Catalog No. D4418) was applied for 4 minutes as a substrate for the peroxidase reaction. All slides were rinsed with tap water, counterstained, dehydrated, and mounted. PBST + 1% BSA served as the diluent for the primary antibodies and ABC Elite reagent. PBST + 1% BSA; and rat IgG (diluted 1:25) served as the diluent for the secondary antibody.

| Primary Antibody | Supplier | Catalog Number |

Concentration/Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse anti-Cytokeratin | AbD Serotec | MCA1907T | 1:40 |

| Mouse anti-Vimentin | AbD Serotec | MCA862 | 1:40 |

| Mouse IgG1 | BD Pharmingen | 554121 | 1:40 (12.5 µg/mL) |

Statistical analysis

Survival was compared among dose groups using Tarone’s life table test to test for dose-related trends (Tarone, 1975) and Cox’s proportional hazards method for pairwise comparisons of each dose group to the control group (Cox, 1972). The poly-3 test, which takes survival differences into account, was used to assess neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesion incidences (Bailer and Portier, 1988, Piegorsch and Bailer, 1997, Portier and Bailer, 1989). When applied to all exposure groups, this test evaluated the significance of a dose-related trend in lesions; when applied to the control group and one exposure group, the test evaluated the significance of the pairwise difference of lesion incidence in the exposed group compared to the control group without correction for multiple testing. Historical control data for the mice were taken from the NTP Historical Control Report (National Toxicology Program, 2013); there were too few historical NTP studies in Wistar Han rats to report historical control data for the rats.

Results

Body weights and survival

There were no treatment-related clinical signs or mortality in rats. Body weights of high dose male rats were 12% lower than controls; the body weights of the other dosed rat groups were within ±10% of controls (Table 1). There were no treatment-related clinical signs or mortality in the 250 or 500 mg/kg mouse groups, and body weights in these treated groups were within ±10% of controls. However, while there were no apparent clinical signs of toxicity in high dose male and female mice (1000 mg/kg), there was early treatment-related mortality that was not associated with tumors. This early mortality may have been related to forestomach toxicity. The high dose male and female mouse groups were, thus, considered inadequate for evaluating the occurrence of tumors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survival and mean second-year body weight in a 2-year study of Tetrabromobisphenol A.

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | No. survivinga | Body weightb | No. survivinga | Body weightb |

| Wistar Han Rats | ||||

| 0 | 33 | 623 (−) | 35 | 338 (−) |

| 250 | 28 | 592 (95) | 34 | 352 (104) |

| 500 | 38 | 562 (90) | 29 | 330 (98) |

| 1000 | 39 | 549 (88) | 33 | 331 (98) |

| B6C3F1/N mice | ||||

| 0 | 33** | 54.3 (−) | 40** | 62.6 (−) |

| 250 | 26 | 56.2 (103) | 31 | 62.9 (100) |

| 500 | 39 | 57.2 (105) | 36 | 59.8 (96) |

| 1000 | 12** | 55.7 (103) | 4** | 48.4 (77) |

n = 50 core animals began the study in each dose group.

Final mean body weight (g) and percent relative to controls in parentheses

In the control row, Tarone’s life table trend test is significant at a nominal p ≤ 0.01; in a dosed row, Cox’s pairwise comparison with the vehicle controls is significant at a nominal p ≤ 0.01.

Histopathology findings

Rat uterine findings

The most significant pathologic findings were treatment-related increases in uterine tumors in rats (Table 2). This included increases in the incidences of uterine adenomas and adenocarcinomas. In addition, there were 6 animals in the treated groups that presented with malignant mixed Müllerian tumors (MMMT). Uterine atypical hyperplasia (considered a preneoplastic lesion) was also found in treated rats.

Table 2.

Treatment-related nonneoplastic and neoplastic uterine lesions in the 2-year Tetrabromobisphenol A female rat study

| Target organa |

Lesion | 0 | 250 | 500 | 1000 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterus Original Transverse review | Adenoma | 0** | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3* | 3 | 8 | 9 | |

| MMMT | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, or MMMT (combined) | 3** | 7 | 11* | 13** | |

| Uterus Residual longitudinal review | Adenoma | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 4** | 9 | 15** | 15** | |

| MMMT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, or MMMT (combined) | 6** | 10 | 16** | 16* | |

| Uterus Original & residual longitudinal reviews (combined) | Endometrium hyperplasia atypical | 2* | 13** | 11** | 13** |

| Adenoma | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 4** | 10 | 15** | 16** | |

| MMMT | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Adenoma, adenocarcinoma, or MMMT (combined) | 6** | 11 | 16** | 19** |

n = 50 animals were examined microscopically in each dose group

Significant at a nominal p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01. Poly-3 trend test in the control column; poly-3 pairwise test under dose groups

Malignant Mixed Müllerian Tumor (MMMT)

Treatment-related increases in rat uterine tumors were seen in the original, residual, and combined original and residual tissue reviews (Table 2). The combined incidence of uterine adenoma, adenocarcinomas, or MMMTs, was significantly increased in the top two dose levels. In the combined original and residual tissues, 6/50 (12%) control rats had uterine tumors versus 11/50 (22%), 16/50 (32%), and 19/50 (38%) in the 250, 500, or 1000 mg/kg groups, respectively. Uterine masses were observed grossly at necropsy in 3 control rats, and, respectively 7, 5, and 9 rats in the 250, 500, or 1000 mg/kg groups. These uterine masses were up to 30 mm × 20 mm in size. Uterine tumor metastases were seen throughout the body. In general, animals with larger uterine masses had many uterine metastatic lesions. Although the numbers were limited, the metastatic rate for MMMTs was 76% (4/6) while the metastatic rate for adenocarcinomas was 24% (11/45).

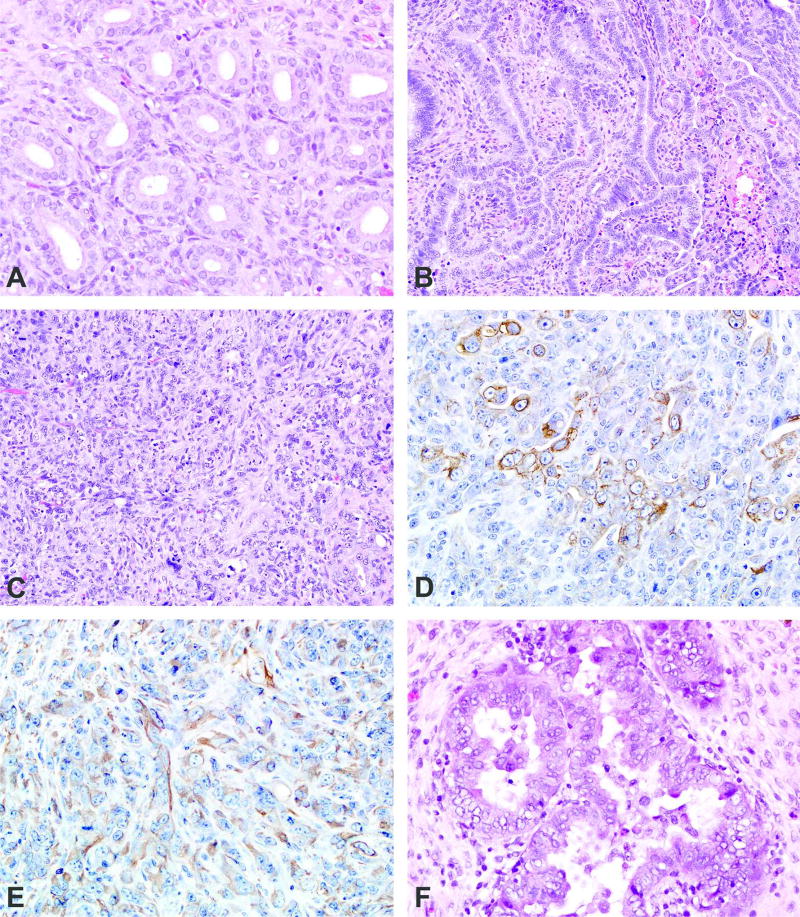

Normal uterine endometrial glands are lined by a single layer of well differentiated cuboidal to columnar epithelium (Figure 1a). Uterine adenomas were solitary and well delineated, characterized by a collection of endometrial glands that were typical in appearance, with little to no compression of surrounding tissue and no invasion of the adjacent endometrium or myometrium. The epithelium consisted of a single layer of well differentiated cuboidal to columnar epithelium without stratification and surrounded by a delicate fibrous stroma. Adenocarcinomas were generally large with invasion into the surrounding myometrium. The neoplastic epithelium was composed of enlarged pleomorphic epithelial cells arranged as solid nests, cords, papillary, or acinar structures, within or supported by a fibrovascular stroma (Figure 1b). There was moderate to marked cellular pleomorphism and atypia. The epithelium was anaplastic in some cases with stratification of multiple cell layers forming solid sheets of epithelial cells that extended through the uterine wall. Large areas of necrosis and suppurative inflammation were also associated with larger tumors. MMMTs were composed of a mixture of neoplastic epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Figure 1c). All MMMTs were large and infiltrative, composed of areas with neoplastic glandular formation and areas of solid neoplastic cells. In the areas of glandular formation, the tumors were similar to adenocarcinomas. In the more solid areas, there was an admixture of neoplastic epithelial and mesenchymal cells arranged in sheets, streams, and/or interweaving bundles. The neoplastic cells were large and pleomorphic with large to elongate nuclei, an open chromatin pattern, a single prominent magenta nucleolus, and bizarre mitotic figures. Cytokeratin and vimentin immunohistochemical stains were used to better characterize these areas (Figures 1d and 1e). Cytokeratin stained the neoplastic epithelial component of MMMTs. The staining was generally cytoplasmic and granular (Figure 1d). Vimentin stained the cytoplasmic portion of neoplastic mesenchymal cells (Figure 1e). In some cases, individual neoplastic cells stained with both cytokeratin and vimentin (dual positivity). In one animal, there was neoplastic bone proliferation (heterologous type of MMMT) (Kaspareit-Rittinghausen and Deerberg, 1990).

Figure 1.

a: An example of the epithelium of normal endometrial glands consisting of a single layer of well differentiated cuboidal to columnar epithelium without stratification and surrounded by a delicate fibrous stroma.

b: A uterine adenocarcinoma composed of neoplastic epithelium with enlarged pleomorphic epithelial cells. These cells are arranged in poorly configured acinar structures, within and supported by a fibrovascular stroma. These cells may also be arranged in solid nests, cords, and papillary structures.

c: A MMMT composed of a mixture of neoplastic epithelial and mesenchymal cells arranged in interweaving bundles. There is marked nuclear atypia with variation in size and shape and prominent, sometimes multiple nucleoli.

d an 1e: Cytokeratin (Figure 1d) and vimentin (Figure 1e) immunohistochemical stains revealed cytoplasmic staining of neoplastic epithelial and mesenchymal cells, respectively, in order to better characterize the MMMTs.

f: An example of atypical glandular endometrial hyperplasia characterized by clusters of enlarged glands separated by little to no stroma and lined by tall, stratified, disorganized epithelium. The epithelium blebs into the lumen and there is cellular proliferation, atypia, and loss of nuclear polarization.

The review of residual tissue revealed another treatment-related lesion, atypical endometrial hyperplasia (Table 2). This lesion involved both the luminal and glandular epithelium. Normal uterine glandular and luminal epithelium consists of a single layer of simple cuboidal to columnar cells with basally located nuclei (nuclear polarization), and the normal renal tubular glands are typically separated by endometrial stroma. In atypical hyperplasia of the surface epithelium numerous small branching papillary projections of epithelium extended into the uterine lumen, occasionally on small fibrovascular stalks. There was frequent epithelial bleb formation, cellular atypical, and loss of nuclear polarization. Clusters of enlarged glands separated by little to no stroma and lined by tall, stratified, disorganized epithelium characterized the glandular atypical endometrial hyperplasia. The thickened epithelium would frequently project into the lumens, forming multiple thickened infoldings and projections. There was cellular pleomorphism, loss of nuclear polarization, karyomegaly and increased mitoses (Figure 1f).

Other findings

In the testis of treated male rats there were a few animals with atrophy of the germinal epithelium, and testicular interstitial cell adenomas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment-related nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions in the 2-year Tetrabromobisphenol A male rat and male and female mouse studies

| Target organa |

Lesion | 0 | 250 | 500 | 1000 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male rat | |||||

| Testis | Germinal epithelium atrophy | 0 | 4 (2.8)b | 1 (3.0) | 2 (3.5) |

| Interstitial cell adenoma | 0* | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Male mouse | |||||

| Large Intestine | Colon/rectum/cecum adenoma or carcinoma | 0* | 0 | 3 | |

| Liver | Clear cell focus | 11 | 10 | 25** | |

| Eosinophilic focus | 20 | 33** | 40** | ||

| Hepatocellular adenoma (multiple) | 12 | 20 | 28* | ||

| Hepatocellular adenoma (includes multiple) | 32 | 33 | 38 | ||

| Hepatoblastoma | 2 | 11** | 8 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 11 | 15 | 17 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatoblastoma | 12 | 24** | 20 | ||

| Kidneyd | Renal tubule cytoplasmic alteration | 0 | 20** (1.9) | 47** (2.4) | 46** (2.6) |

| All organs | Hemangioma | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 1* | 5 | 8* | ||

| Hemangioma or hemangiosarcoma | 3* | 5 | 9 | ||

| Kidneyd | Renal tubule cytoplasmic alteration | 0 | 20** (1.9) | 47** (2.4) | 46** (2.6) |

| Forestomachc | Ulcer | 9 (1.8) | 9 (2.4) | 19* (2.2) | 28** (2.4) |

| Infiltration cellular mononuclear cell | 5 (1.6) | 8 (1.8) | 21** (2.1) | 27** (2.3) | |

| Inflammation | 9 (1.3) | 10 (1.7) | 20* (2.2) | 26** (2.3) | |

| Epithelium hyperplasia | 10 (1.7) | 13 (2.2) | 27** (2.8) | 28** (2.7) | |

| Female mouse | |||||

| Forestomachd | Ulcer | 2 (2.0) | 15** (2.0) | 40** (2.2) | 38** (2.1) |

| Infiltration cellular mononuclear cell | 2 (3.0) | 13** (2.2) | 33** (2.4) | 28** (1.8) | |

| Inflammation | 2 (3.0) | 14** (1.4) | 41** (2.0) | 37** (2.2) | |

| Epithelium hyperplasia | 4 (2.5) | 16** (2.6) | 39** (3.0) | 39** (2.3) | |

n = 50 animals were examined microscopically in each dose group, except as noted

Mean severity grade

n = 49 animals were examined microscopically in the 1000 mg/kg group

n = 48 animals were examined microscopically in the 1000 mg/kg group

Significant at a nominal p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01 Poly-3 trend test under control column; pairwise test under dose groups

Sufficient number of high dose mice did not live for two years, and this group was not used in cancer evaluations.

A few intestinal tumors were found in treated male mice and were diagnosed as either adenoma or carcinoma of the cecum or colon. When these tumors were combined (0/50, 0/50, 3/50 (6%) in the 0, 250, and 500 mg/kg groups respectively), there was a statistically significant positive trend and the incidence in the 500 mg/kg group exceeded the historical control ranges for tumors of the large intestines among corn oil gavage (0/250, 0%) and all routes controls (4/950, 0%–2%) (Table 3). In addition to these large intestinal tumors in male mice, an adenoma of the rectum occurred in one female mouse in the 500 mg/kg group.

The occurrence of hepatoblastomas in male mice with incidences of 2/50, 11/50 and 8/50 (0, 250, and 500 mg/kg groups, respectively) was considered to be evidence of a carcinogenic effect (Table 3). The incidence in the 250 and 500 mg/kg groups (22% and 16%, respectively) was at least fourfold greater than the incidence for this tumor in the concurrent vehicle controls (4%) and was outside of the range for this tumor in the historical controls (9.250, 0%–6%) for corn oil gavage controls and for all routes historical controls (40/949, 0% – 12%). There was supportive evidence for a liver carcinogenic effect because of the increases in liver foci and multiple hepatocellular adenomas in treated groups of male mice.

The occurrence of hemangiosarcoma (all organs) in male mice was considered to be a carcinogenic effect because of the significantly increased incidence at 500 mg/kg and the trend test was significant (Table 3). There were no treatment-related tumor responses in female mice.

The incidence of renal tubule cytoplasmic alteration was significantly increased in treated male mice in the 2-year study (Table 3). Cytoplasmic alteration of the renal tubule is a lesion that is defined as the reduction or loss of normal vacuoles in the proximal tubules of the outer cortex in male mice. These are autophagic vacuoles that are part of the normal sequestration and degradation of organelles and membrane trafficking and recycling in the renal proximal tubular cells (Koenig et al., 1980).

Forestomach lesions that were significantly increased in treated mice included ulcers, mononuclear cellular infiltrates, inflammation and hyperplasia. The mononuclear cellular infiltrates were part of a robust immune response present within the mucosa, submucosa, and tunica muscularis underlying areas of ulceration. This lesion consisted of a collection of immune cells, predominately lymphocytes, with occasional germinal center formation. The inflammation and hyperplasia were also secondary to the ulceration..

Discussion

The U. S. EPA currently assigns a low hazard level for TBBPA exposure (U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2008). However, the studies reported here demonstrate that long-term TBBPA exposure induced uterine tumors in rats. Additional sites for TBBPA tumor induction included testis (rat), and liver, large intestine, and vascular system (male mice).

The initial rat uterine neoplastic findings were based on the traditional NTP histopathology review of a transverse section through each uterine horn 0.5 cm from the cervix/body of the uterus. Cervix and vagina were not present in the original evaluation, except where a gross identification of a lesion was made at necropsy. Ovaries and oviducts were all collected and examined in the original review and no treatment related lesions were present.

The main reason for the second uterine tissue review (i. e. residual longitudinal uterine tissue evaluation) was to determine the site of origin for the grossly identified cervical and vaginal tumors. In the second uterine tissue review, longitudinal sectioning was done to afford the most area of tissue for evaluation. There was no sampling bias because all uterine horns, cervices, and vaginas from all animals were collected and evaluated in this residual uterine tissue review.

The findings from the initial transverse uterine tissue evaluation, the second longitudinal uterine tissue evaluation, and the combined initial and residual longitudinal uterine evaluations showed treatment-related uterine tumors in rats. Although a call of clear carcinogenicity would have been made on the initial evaluation, the additional tumors identified in the residual longitudinal review supported, and provided more confidence for, the initial findings.

TBBPA uterine lesions in the rat included increases in adenomas, adenocarcinomas, malignant mixed Müllerian tumors (MMMTs), and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. The uterine adenomas were well-circumscribed endometrial masses with no evidence for invasion into the myometrium. In contrast, uterine adenocarcinomas and MMMTs were less well circumscribed, with evidence of invasion into the myometrium and in some cases metastasis to other tissues.

The MMMTs are uncommon tumors thought to arise from a pluripotent Müllerian duct cell. They are composed of a mixture of neoplastic epithelial and neoplastic mesenchymal cells. For statistical analysis, MMMTs were combined with the uterine adenomas and adenocarcinomas because, based on our knowledge of histogenesis of this tumor from the human literature, the epithelial component is considered to be the “driving force” of the tumor and the mesenchymal component is considered to be derived from the epithelial component. Evidence for this histogenesis theory includes clinical, histopathological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, tissue culture, and molecular data (McCluggage, 2002). As an example, the behavior of human MMMTs is more related to the type and grade of the epithelium rather than the mesenchymal component. For this reason, treatments are generally aimed at the epithelial component. Moreover, metastases tend to be the epithelial component, as they all were in this study.

Dysregulation of the cell cycle and apoptotic regulatory proteins have been reported to be involved in MMMT cancer pathways (Kanthan et al., 2010). In humans, MMMTs account for about 5% of all malignant tumors derived in the body of the uterus, and are highly malignant and associated with a poor prognosis (Gupta et al., 2012, Voutsadakis, 2012). Risk factors are similar to those for uterine adenocarcinomas and include obesity, exogenous estrogen therapies, nulliparity, tamoxifen therapy, and pelvic irradiation. There are two types of MMMTs that display differentiation along multiple pathways (van den Brink-Knol and van Esch, 2010): the more common homologous type contains a sarcomatous component that is made up of tissues normally present in the uterus such as endometrial, fibrous, or smooth muscle tissues; whereas the heterologous type is made up of both uterine tissue and tissue not normally present in the uterus such as cartilage, skeletal muscle, or bone. Both MMMT tumor types were seen in this TBBPA study. MMMTs are rarely seen in rodents, but have previously been described as rare spontaneous tumors in the Wistar rat (van den Brink-Knol and van Esch, 2010).

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia was significantly increased in the treated groups of rats and was only identified in the residual longitudinal study because of the additional uterine tissue available for evaluation. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia is considered a preneoplastic lesion in women (Bartels et al., 2012, van der Zee et al., 2013, Silverberg, 2000). It is diagnosed as simple (which is rare) or complex (which is more common), depending on the architectural changes in the lesion. In this rat study, the atypical hyperplasia was morphologically consistent with the complex type. Cystically dilated glands with mostly pseudostratified epithelium define simple atypical hyperplasia whereas the complex atypical hyperplasia is defined by a greater degree of glandular proliferation and reduction of intervening stroma. In both, there are atypical changes in epithelial cells, including cell stratification, tufting, and loss of nuclear polarity, enlarged nuclei, and an increase in mitotic activity. These changes are similar to those seen in true cancer cells, but atypical hyperplasia does not show invasion into the surrounding connective tissue. Most cases of atypical hyperplasia in women result from high levels of estrogens with insufficient levels of progesterone-like hormones. Risk factors include obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, estrogen producing tumors (e.g., granulosa cell tumor), and some estrogen replacement therapies. The presence of atypical hyperplasia is considered a significant risk factor for the development or coexistence of endometrial cancer. Among patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, about 25% will eventually develop cancer (Kurman et al., 1985).

In the present study, a major hypothesis for the TBBPA-related uterine cancer formation is through effects on estrogen homeostasis. TBBPA caused weak cell proliferation response in the estrogen-sensitive human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, and was not predicted to be a uterine carcinogen (Kitamura et al., 2005, Samuelsen et al., 2001, Uhnakova et al., 2011). However, other studies suggest that exposure to TBBPA could result in decreased estrogen metabolism. TBBPA is detoxicated and eliminated by conjugation with glucuronic acid and/or sulfonate (Figure 2) (Hakk et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 2014a, Kuester et al., 2007). Estradiol also utilizes sulfotransferases for its systemic transport and elimination (Raftogianis et al., 2000), and binding affinities for TBBPA and estradiol to sulfotransferases are similar (Gosavi et al., 2013). In humans, formation of estrogen sulfoconjugates results in loss of binding to the estrogen receptor as well as increased renal excretion of estrogen (Raftogianis et al., 2000). By competing with estrogen for sulfotransferase, TBBPA exposure could decrease estrogen excretion, resulting in elevated levels of the hormone in the uterus, and, thus, increase the carcinogenic risk at this site (Karageorgi et al., 2011). TBBPA-induced uterine tumors were not seen in mice, and this may be because estrogen homeostasis is less affected in mice than in rats due to differences in the capacity and/or capability of conjugating enzymes (Burka et al., 1996). In a previous study, bromoethane exposure was associated with uterine tumor formation in mice: however, no bromoethane effects on estrogen homeostasis were evident (Bucher et al., 1995).

Figure 2.

Proposed TBBPA metabolism in rats. Adapted from: (Chignell et al., 2008, Hakk et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 2014a, Kuester et al., 2007, Schauer et al., 2006)

Another way by which TBBPA may enhance estrogen activity in rats is suggested by the finding that TBBPA inhibits hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase-17β (HSD17β) in in vitro assays (NIH Molecular Libraries Screening Center Network, 2014 (accessed)). HSD17β converts active estradiol to less active estrone (Blom et al., 2001, Karageorgi et al., 2011), and, thus, a TBBPA-induced inhibition of HSD17β could increase estrogen activity. Elevated or prolonged estrogen levels in the uterus, could result in increased levels of mutagenic estrogen metabolites, such as catechols, capable of forming DNA adducts (Liehr, 2000) and elevating the risk for genetic damage (Cavalieri and Rogan, 2014). Currently, work is being conducted at the gene expression level to elucidate effects of TBBPA on estrogen homeostasis in female Wistar Han rats.

In rats there were a few testicular tumors in the TBBPA treated groups. The occurrence of these tumors may also have been related to altered homeostasis (in this case alternations in male hormones). Studies in the literature report that TBBPA may have a weak androgenic activity (Huang et al., 2013). Metabolic activation of TBBPA could be a causal factor for toxicities in other tissues, such as the lesions observed in the liver of mice. A mode-of-action has been proposed to explain similar effects in studies of other brominated chemicals (Dunnick et al., 1997). That is, cleavage of a bromine-carbon bond of TBBPA could be speculated to result in formation of DNA-damaging free radicals and adducts. However, evidence indicates that debromination is not a major metabolic pathway for TBBPA in rats. Low concentrations of conjugated or free tribromobisphenol A were detected in plasma and feces samples of some male rats receiving an oral dose of 300 mg TBBPA/kg (Schauer et al., 2006) (Figure 2). However, debrominated metabolites were not detected in plasma or feces of several well-conducted metabolism studies of orally administered TBBPA to rats (Hakk et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 2014a, Kuester et al., 2007). Another putative reactive metabolite of TBBPA, 2,6-dibromobenzoquinone (Figure 2) radical, was detected by electron paramagnetic resonance (spin-trapping) in bile following TBBPA administration to rats (Chignell et al., 2008). The radical would arise as a result of oxidative cleavage of the TBBPA molecule. However, this pathway of radical formation in rats also appears to be minor and was not observed in other in vivo metabolism studies of TBBPA (Hakk et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 2014b, Kuester et al., 2007). It is plausible that reactive intermediates play a greater role in TBBPA-induced toxicity in mice based on the differences in target tissues between the two species. For instance, the lesions observed in target tissues of mice could result from oxidative stress (e.g. forestomach toxicity). Further, as animals age they have reduced capacity to combat oxidative damage, and this “aging” effect may have played a role in this toxicity (Kregel and Zhang, 2007, Rahman et al., 2001, Salmon et al., 2010). Finally, elemental bromine itself is a known irritant to skin, lung, and the gastrointestinal tract (Makarovsky et al., 2007). Common target tissues for the brominated chemicals studied previously by the NTP were lung, forestomach, and intestines (Dunnick et al., 1997).

It is unusual to find evidence of chemical-induced uterine tumors in rodent toxicity studies. The Interagency for Research on Cancer recently reviewed those chemicals causing uterine cancers in humans and animals (International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2012). Among these chemicals is tamoxifen, which causes uterine cancers in both Wistar rats and in humans. It is unknown if TBBPA poses a carcinogenic risk to humans; however, it seems plausible that TBBPA exposure could influence estrogen homeostasis in humans in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, other environmental pollutants may compete with estrogen sulphonation (Gosavi et al., 2013). Additive effects of these exposures could decrease the internal TBBPA dose needed for a biological response.

The occurrence of TBBPA uterine tumors in the present study is of concern because TBBPA exposure is widespread and endometrial tumors are the fourth most common malignancy in women in the U. S. with an estimated 50,000 new cases per year (Siegel et al., 2013). Endometrial cancer in humans is most often associated with estrogen exposure (Rizner, 2013). The results of the studies reported here suggest that long-term exposure to TBBPA may lead to carcinogenic effects in rodents, and further work is needed to understand TBBPA cancer mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), Research Triangle Park, NC. Authorial contributions by J. M. Sanders were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. The in-life portion of this study was conducted under the supervision of Dr. M. Hejtmanicik, Battelle Columbus, and Columbus, Ohio under NIEHS contract N01-ES-55541. Statistical support was provided under NIEHS contract HHSN291200555547C. We thank Dr. G. Knudsen, NCI, RTP, NC and Dr. A. Pandiri, NIEHS, RTP, NC for their review of the manuscript.

References

- Bailer AJ, Portier CJ. Effects of treatment-induced mortality and tumor-induced mortality on tests for carcinogenicity in small samples. Biometrics. 1988;44:417–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels PH, Garcia FA, Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Curtin J, Lim PC, Hess LM, Silverberg S, Zaino RJ, Yozwiak M, Bartels HG, Alberts DS. Karyometry in atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum LS, Staskal DF. Brominated flame retardants: cause for concern? Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:9–17. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom MJ, Wassink MG, Kloosterboer HJ, Ederveen AG, Lambert JG, Goos HJ. Metabolism of estradiol, ethynylestradiol, and moxestrol in rat uterus, vagina, and aorta: influence of sex steroid treatment. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2001;29:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorman GA, Eustis SL. The pathology working group as a means for assuring pathology quality in toxicologic studies. In: Whitmire C, Davis CL, Bristol DW, editors. Managing conduct and data quality of toxicologic studies. Princeton Scientific Publishing; Princeton: 1986. pp. 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher JR, Morgan DL, Adkins B, Jr, Travlos GS, Davis BJ, Morris R, Elwell MR. Early changes in sex hormones are not evident in mice exposed to the uterine carcinogens chloroethane or bromoethane. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1995;130:169–173. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burka LT, Sanders JM, Matthews HB. Comparative metabolism and disposition of ethoxyquin in rat and mouse. II. Metabolism. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems. 1996;26:597–611. doi: 10.3109/00498259609046736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri E, Rogan E. The molecular etiology and prevention of estrogen-initiated cancers: Ockham's Razor: Pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate. Plurality should not be posited without necessity. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2014;36C:1–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 199–2012 Survey Content Brochure. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

- Chignell CF, Han SK, Mouithys-Mickalad A, Sik RH, Stadler K, Kadiiska MB. EPR studies of in vivo radical production by 3,3',5,5'-tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in the Sprague-Dawley rat. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2008;230:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat Soc. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnick JK, Heath JE, Farnell DR, Prejean JD, Haseman JK, Elwell MR. Carcinogenic activity of the flame retardant, 2,2-bis(bromomethyl)-1,3-propanediol in rodents, and comparison with the carcinogenicity of other NTP brominated chemicals. Toxicol Pathol. 1997;25:541–548. doi: 10.1177/019262339702500602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Risk Assessment Report. European Union Risk Assessment Report: 2,2, 6,6 -Tetrabromo-4,4 -isopropylidenediphenol (Tetrabromobisphenol-A or TBBP-A). Part II. Human Health. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; Luxembourg: 2006. http://europa.eu/index_en.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Gosavi RA, Knudsen GA, Birnbaum LS, Pedersen LC. Mimicking of estradiol binding by flame retardants and their metabolites: a crystallographic analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:1194–1199. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Dudding N, Smith JH. Eight cases of malignant mixed mullerian tumor (carcinosarcoma) of the uterus: Findings in surepath cervical cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;42:165–169. doi: 10.1002/dc.22910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakk H, Larsen G, Bergman A, Orn U. Metabolism, excretion and distribution of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A in conventional and bile-duct cannulated rats. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems. 2000;30:881–890. doi: 10.1080/004982500433309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers T, Kamstra JH, Sonneveld E, Murk AJ, Kester MH, Andersson PL, Legler J, Brouwer A. In vitro profiling of the endocrine-disrupting potency of brominated flame retardants. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006;92:157–173. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardisty JG, Boorman GA. National Toxicology Program pathology quality assurrance procedures. In: Whitmire C, Davis CL, Bristol DW, editors. Managing conduct and data quality of toxicologic studies. Princeton Publishing Company; Princeton: 1986. pp. 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Huang GY, Ying GG, Liang YQ, Zhao JL, Yang B, Liu S, Liu YS. Hormonal effects of tetrabromobisphenol A using a combination of in vitro and in vivo assays. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;157:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) IARC mongraphs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Pharmaceuticals: A review of human carcinogens. IARC; Lyon, France: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kanthan R, Senger JL, Diudea D. Malignant mixed Mullerian tumors of the uterus: histopathological evaluation of cell cycle and apoptotic regulatory proteins. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:60. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgi S, McGrath M, Lee IM, Buring J, Kraft P, De Vivo I. Polymorphisms in genes hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase-17b type 2 and type 4 and endometrial cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspareit-Rittinghausen J, Deerberg F. Spontaneous malignant mixed mullerian tumors and rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 1990;18:417–422. doi: 10.1177/019262339001800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Suzuki T, Sanoh S, Kohta R, Jinno N, Sugihara K, Yoshihara S, Fujimoto N, Watanabe H, Ohta S. Comparative study of the endocrine-disrupting activity of bisphenol A and 19 related compounds. Toxicol Sci. 2005;84:249–259. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen GA, Sanders JM, Sadik AM, Birnbaum LS. Disposition and kinetics of tetrabromobisphenol A in female Wistar Han rats. Toxicology Reports. 2014a doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.03.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen GA, Sanders JM, Sadik AM, Birnbaum LS. TITLE Disposition and kinetics of Tetrabromobisphenol A in female Wistar Han rats. Toxicol Rep. 2014b;1:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H, Goldstone A, Blume G, Lu CY. Testosterone-mediated sexual dimorphism of mitochondria and lysosomes in mouse kidney proximal tubules. Science. 1980;209:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.7403864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel KC, Zhang HJ. An integrated view of oxidative stress in aging: basic mechanisms, functional effects, and pathological considerations. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R18–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00327.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuester RK, Solyom AM, Rodriguez VP, Sipes IG. The effects of dose, route, and repeated dosing on the disposition and kinetics of tetrabromobisphenol A in male F-344 rats. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2007;96:237–245. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of "untreated" hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403–412. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<403::aid-cncr2820560233>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law RJ, Bersuder P, Allchin CR, Barry J. Levels of the flame retardants hexabromocyclododecane and tetrabromobisphenol A in the blubber of harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) stranded or bycaught in the U.K., with evidence for an increase in HBCD concentrations in recent years. Environmental science & technology. 2006;40:2177–2183. doi: 10.1021/es052416o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr JG. Is estradiol a genotoxic mutagenic carcinogen? Endocrine reviews. 2000;21:40–54. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarovsky I, Markel G, Hoffman A, Schein O, Brosh-Nissimov TM, Finkelstien A, Tashma Z, Dushnitsky T, Eisenkraft A. Bromine--the red cloud approaching. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9:677–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:321–325. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.5.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program. Toxicology studies of teterabromobisphenol A (Cas no. 79-94-7) in F344/NTac rats and B6C3F1/N mice and toxicology and carcinogeogenesis studies of tetrabromobisphenol A in Wistar Han [Crl:WI(Han)] rats and B6C3F1/N mice. NTP Technical Report. 2013;587 [Google Scholar]

- NIH Molecular Libraries Screening Center Network. BioAssay: AID 893 qHTS Assay for Inhibitors of HSD17B4, hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase. 2014;4 (accessed). http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?cid=6618. [Google Scholar]

- Piegorsch WW, Bailer AJ. Statistics for Environmental Biology and Toxicology. In: Hall Ca., editor. vol. Section 6.3.2. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Portier CJ, Bailer AJ. Testing for increased carcinogenicity using a survival-adjusted quantal response test. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;12:731–737. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftogianis R, Creveling C, Weinshilboum R, Weisz J. Estrogen metabolism by conjugation. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000:113–124. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman F, Langford KH, Scrimshaw MD, Lester JN. Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants. The Science of the total environment. 2001;275:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)00852-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizner TL. Estrogen biosynthesis, phase I and phase II metabolism, and action in endometrial cancer. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2013;381:124–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon AB, Richardson A, Perez VI. Update on the oxidative stress theory of aging: does oxidative stress play a role in aging or healthy aging? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsen M, Olsen C, Holme JA, Meussen-Elholm E, Bergmann A, Hongslo JK. Estrogen-like properties of brominated analogs of bisphenol A in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2001;17:139–151. doi: 10.1023/a:1011974012602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer UM, ouml, lkel W, Dekant W. Toxicokinetics of tetrabromobisphenol a in humans and rats after oral administration. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:49–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg SG. Problems in the differential diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2000;13:309–327. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarone RE. Tests for trend in life table analysis. Biometrika. 1975;62:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Partnership to evaluate flame retardants in printed circuit boards. 2008 http://www.epa.gov/dfe/pubs/projects/pcb/full_report_pcb_flame_retardants_report_draft_11_10_08_to_e.pdf.

- U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. [accessed June 2013];Flame Retardants in Printed Circuit Boards Partnership. 2013 http://www.epa.gov/dfe/pubs/projects/pcb/index.htm.

- U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Flame retardants in printed circuit boards. 2014 http://www.epa.gov/dfe/pubs/index.htm.

- Uhnakova B, Ludwig R, Peknicova J, Homolka L, Lisa L, Sulc M, Petrickova A, Elzeinova F, Pelantova H, Monti D, Kren V, Haltrich D, Martinkova L. Biodegradation of tetrabromobisphenol A by oxidases in basidiomycetous fungi and estrogenic activity of the biotransformation products. Bioresource technology. 2011;102:9409–9415. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink-Knol H, van Esch E. Spontaneous malignant mixed Mullerian tumor in a Wistar rat: a case report including immunohistochemistry. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:1105–1110. doi: 10.1177/0300985810374840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven LT, Van de Kuil T, Verhoef A, Verwer CM, Lilienthal H, Leonards PE, Schauer UM, Canton RF, Litens S, De Jong FH, Visser TJ, Dekant W, Stern N, Hakansson H, Slob W, Van den Berg M, Vos JG, Piersma AH. Endocrine effects of tetrabromobisphenol-A (TBBPA) in Wistar rats as tested in a one-generation reproduction study and a subacute toxicity study. Toxicology. 2008;245:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee M, Jia Y, Wang Y, Heijmans-Antonissen C, Ewing PC, Franken P, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Burger CW, Fodde R, Blok LJ. Alterations in Wnt-beta-catenin and Pten signalling play distinct roles in endometrial cancer initiation and progression. J Pathol. 2013;230:48–58. doi: 10.1002/path.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutsadakis IA. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in the pathogenesis of uterine malignant mixed Mullerian tumours: the role of ubiquitin proteasome system and therapeutic opportunities. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0792-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalko D, Prouillac C, Riu A, Perdu E, Dolo L, Jouanin I, Canlet C, Debrauwer L, Cravedi JP. Biotransformation of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol A by human and rat sub-cellular liver fractions. Chemosphere. 2006;64:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]