Abstract

Study Objectives:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a prevalent, chronic, itchy skin condition. Children undergoing polysomnography (PSG) may coincidentally have AD. Many children with AD have sleep disturbances. Our study aimed to characterize limb movements in children with AD and their effect on sleep.

Methods:

A retrospective chart review was conducted for children who underwent comprehensive attended PSG and had AD. PSG sleep parameters were compared to published normative data. A subset of patients with markedly elevated total limb movements was further compared to a matched group of patients with a diagnosis of periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) and no history of AD.

Results:

There were 34 children with AD 6.36 ± 3.21 years (mean ± standard deviation), 50% female and with mild to moderate AD. There was increased wake after sleep onset (WASO = 46.0 ± 37.8 minutes), sleep onset latency (46.5 ± 53.0 minutes) and total limb movement index (13.9 ± 7.5 events/h) compared to normative values. Although our cohort was mostly mild AD, 7 of the 34 children with AD (20%) had a total limb movement index during sleep > 15 events/h. Increased total limb movements in PLMD versus patients with AD was most notable during stage N2 sleep (38 ± 17 versus 22 ± 7, P = .01, respectively).

Conclusions:

We found altered PSG parameters in children with AD, suggesting that clinicians should consider the diagnosis when affected children undergo PSG. Although our AD cohort was mild, we still determined a need to consider AD when diagnosing PLMD given the presence of elevated total limb movements in children with AD.

Citation:

Treister AD, Stefek H, Grimaldi D, Rupani N, Zee P, Yob J, Sheldon S, Fishbein AB. Sleep and limb movement characteristics of children with atopic dermatitis coincidentally undergoing clinical polysomnography. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(8):1107–1113.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, periodic limb movements of sleep, polysomnography, pruritus, sleep

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a prevalent, chronic, itchy skin condition that frequently results in sleep disturbance. Children undergoing polysomnography (PSG) may coincidentally be affected; however, characteristics of this population have never been evaluated in a retrospective chart review of patients undergoing PSG.

Study Impact: We found a population with relatively mild atopic dermatitis, yet still with increased wake after sleep onset and sleep fragmentation on PSG. Furthermore, given the frequent limb movements noted during sleep in atopic dermatitis, it should be considered when making the diagnosis of periodic limb movement disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic pruritic inflammatory skin disease and cross-sectional studies across multiple countries have noted that it is prevalent in up to 20% of children.1 In addition, it interferes with sleep in more than 50% of affected children.2 Most parents who are interviewed report that their children with AD have sleep problems, noting that scratching leads to difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep.2,3 Sleep fragmentation is common,4–8 and ultimately leads to ∼50 minutes of sleep lost per night in moderate/severe AD.8 This sleep loss results in increased daytime sleepiness as well as neurocognitive and behavioral effects.9 The few pediatric studies that have applied polysomnography (PSG) to analyze sleep architecture in these children suggests a significant correlation between disease severity of AD and degree of sleep fragmentation.4,10 Although it is clear that severe AD results in profound sleep disturbance, the degree of sleep disturbance related to AD in a general population of children undergoing PSG is not known. Given that most patients with AD are not evaluated by PSG,11 there is a need to characterize sleep in children whose skin disease may be overlooked by sleep medicine clinicians as a contributing factor to sleep disruption.

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is one sleep disorder that is particularly important to differentiate from AD. It has been previously described in a case report that children with AD can be incorrectly assessed as having periodic limb movements in sleep, when in fact they are just experiencing itch-induced scratching.12 There is also a purported increased risk of restless leg syndrome in AD.13 Because it can be difficult to inspect PSG video and interpret whether movement is associated with itch, there is a need to better understand the difference in limb movements between children with AD and those with PLMD. With this understanding, clinicians may better differentiate these two conditions, allowing for correct therapeutic intervention. We initiated this study to (1) compare PSG sleep parameters in children undergoing PSG who coincidentally have AD to normative data and (2) compare PSG sleep parameters of children with AD and increased limb movements during sleep to children with a diagnosis of PLMD.

METHODS

Study Population

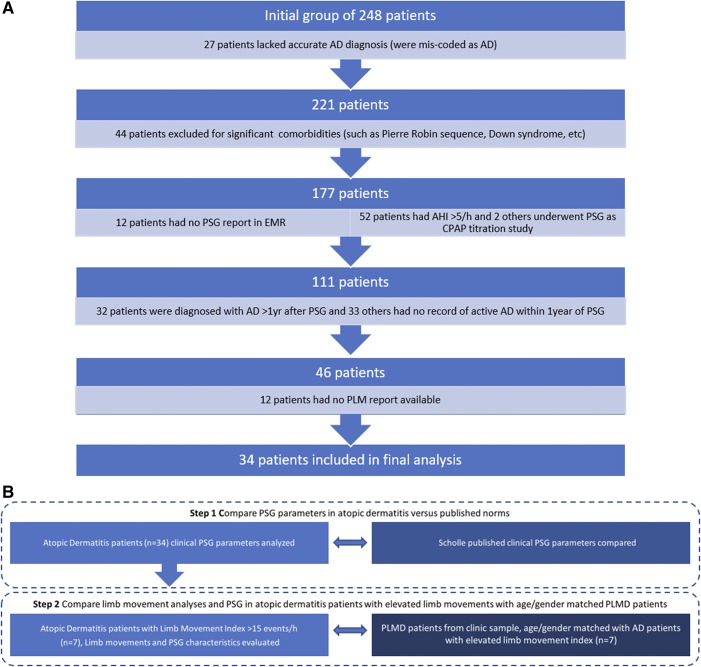

We retrospectively identified patients between 1.5 to 17 years of age who underwent PSG at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago between 2004 and 2014 and who had a diagnosis of AD (n = 248). Patients who had an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) > 5 events/h, who were undergoing PSG for titration of continuous positive airway pressure or who had a diagnosis of a genetic syndrome, birth defect, or chronic disease thought to potentially affect sleep were excluded. Our final inclusion criterion was that AD had to have been clearly documented in the chart as active in the year of the PSG (Figure 1A). The overall study design is summarized in Figure 1B. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1. Flow chart and study design.

(A) Flow chart of patients included in the AD final analysis cohort with reasons for exclusion. (B) Overall study design. Step 1 compares PSG parameters in children with AD undergoing PSG versus the general population. Step 2 compares limb movement analyses and PSG in a subset of children with AD and elevated limb movements versus PLMD. AD = atopic dermatitis, AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, EMR = emergency medical record, PLM = periodic limb movement, PLMD = periodic limb movement disorder, PSG = polysomnography.

Patient Clinical Features

Patient age, sex, history of atopic disease (allergic rhinitis, asthma, or food allergy), and severity of AD were ascertained from patient records. AD severity was rated as mild or moderate based on medication regimen with mild defined as use of a class VI or lower potency topical corticosteroid and moderate as use of class II intermittently, or class III to class V topical corticosteroid regularly at the time of PSG.14 No patients were using a class I topical corticosteroid and none were on systemic therapy for AD.

PSG Analysis

PSG reports from overnight laboratory-based sleep studies were reviewed for total sleep time (TST), sleep latency (SL), sleep stages (N1, N2, N3, and R [REM]), sleep efficiency (SE), AHI, arousal index during sleep and total limb movement index during sleep (LMI) or total limb movement index during sleep with associated arousals (LMAI). All PSG studies were conducted and scored according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines in an accredited facility by a physician.15 Data were gleaned from clinical reports and confirmed by reevaluation. Of note, the values for limb movements during wakefulness were scored by the automatic scoring method of the PSG as this is not a value that is typically scored.

Comparison to Normative Values

Because this was a retrospective study of children with AD, a normal control group was not available. Alternatively, we chose to compare PSG results for our cohort of patients with mild to moderate AD (m-AD) to normative values reported in a series of studies by Scholle et al from 209 healthy German children who underwent single-night PSG in 16 different sleep laboratories and whose results were scored according to AASM guidelines.16–18 The Scholle et al studies outline normative values for quantitative sleep data, cardiorespiratory parameters, and arousal events for the children according to age group and stage of maturation. We compared the PSG values in our cohort of children with m-AD to the normative values reported by Scholle et al for respective age ranges.

Questionnaire Analysis

We retrospectively reviewed our clinic’s own standardized clinical parent questionnaires completed at the time of PSG that contained information about the child’s daytime and nighttime behaviors as well as observed functioning. We recorded responses to the following questions: whether the child was witnessed kicking their legs in their sleep, if they awoke with leg pains, and if they had difficulty keeping their legs still during the day.

Limb Movement Analysis

A subset of patients with m-AD, with LMI > 15 events/h, had further PSG characterization. These children were matched by age, AHI, and sex to children with a known diagnosis of PLMD and no history of AD who underwent PSG at Lurie Children’s Hospital between 2012 and 2016.

A trained PSG technician, who was blinded to disease group, independently re-reviewed and scored all significant limb events according to AASM guidelines for both the AD with elevated limb movements and PLMD cohorts. Because these totals include both isolated and periodic limb movements (although all movements were individually scored so one periodic limb movement series that might include four limb events, would be scored as four movements), we refer to them as total limb movements.

Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) (version 25; IBM Corporation, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Because of a lack of normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare PSG parameters of the AD and PLMD groups. The Mann-Whitney U test is a nonparametric test that can compare means, but does not have any assumptions with regard to distribution. A value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Other data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, which allowed us to characterize our collected data and compare it to previous research. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Demographics

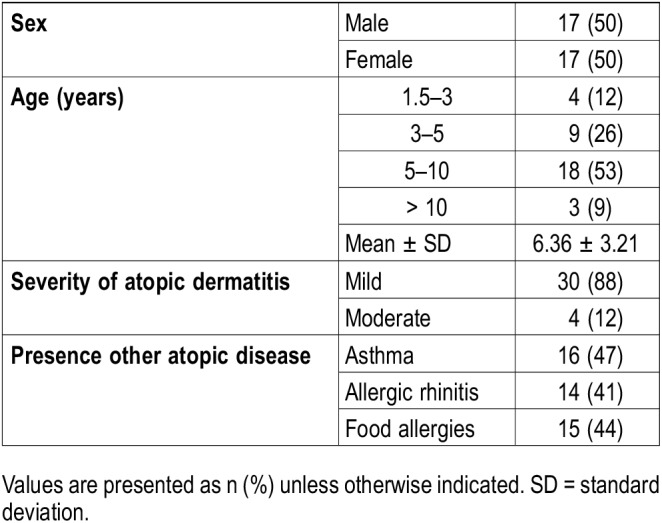

A total of 34 patients (6.36 ± 3.21 years, 50% female) with PSG and AD were included. Four patients had moderate AD and the remainder had mild disease (Table 1). Several patients had an additional atopic condition. Patients were undergoing PSG for a variety of reasons including: hyperactivity/inattention (8), bruxism (6), scratching (1), witnessed apneas (6), snoring (27), loud or mouth breathing (26), restless sleep (12), kicking in sleep (12), leg or growing pains (5), daytime sleepiness (8), OSA status post tonsillectomy (1), tonsillar hypertrophy (8), sleepwalking (2), enuresis (3), and nightmares (3). Upon review of charts, 20 patients had received a diagnosis of OSA (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9 codes 327.23 or G47.33), though mean AHI was 1.2 events/h. In the parental questionnaire, 19 parents reported that their child kicks his or her legs during sleep, 7 reported a child waking up with leg pain, and 12 reported that their child had difficulty keeping his or her legs still during the daytime.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of patients with atopic dermatitis.

PSG Features

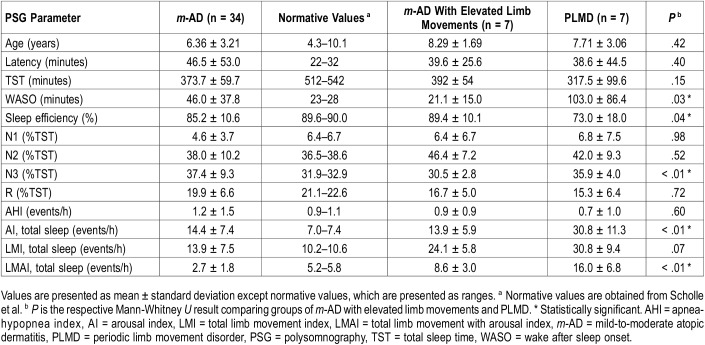

The average sleep latency for all patients with m-AD was elevated at 46.5 ± 53.0 minutes as compared to 22–32 minutes reported by Scholle et al for healthy children of similar ages. TST was decreased at 373 ± 60 minutes (normative value = 512–542 minutes) and average SE was slightly decreased at 85 ± 11% (normative value = 90%). Sleep architecture was somewhat altered in our cohort of patients with m-AD. The patients with m-AD on average spent less time in stage N1 sleep than published standards (4.6 ± 3.7% versus 6% to 7%) and more time in stage N3 sleep (37.4 ± 9.3% versus 32% to 33%), though percentage of time in stage N2 and R sleep were similar. Of note, 11 of the 34 patients with AD had decreased stage R sleep (Table 2).

Table 2.

Polysomnography parameters in children with atopic dermatitis compared to normative data and children with periodic limb movement disorder.

Average wake after sleep onset (WASO) for the m-AD cohort was 46 ± 38 minutes, elevated above the 23–28 minutes seen in healthy children. Average arousal index for the group was 14.4 ± 7.4 events/h, markedly higher than the 7 events/h reported by Scholle et al in similar ages. The average AHI for the group was 1.2 ± 1.5 events/h (Table 2). However, upon chart review, 20 patients had a diagnosis of OSA as defined by ICD-9 codes 327.23 and G47.33.

Limb Movements During Sleep

Average LMI for the m-AD group was 13.9 ± 7.5 events/h, greater than the 10 events/h reported for healthy children of similar ages. The most frequent total limb movements occurred in stage N1 sleep, followed by stage R, N2, and N3 sleep (Table 2). Average LMAI was 2.7 ± 1.8 events/h, less than the 5.2–5.8 events/h reported by Scholle et al.

PSG Features in Patients With AD and Elevated LMI Versus Patients With PLMD

We found 7 of the 34 children with AD (20%) had LMI > 15 events/h. We compared this subgroup of children with m-AD and elevated LMI to patients with PLMD. The comparison of sleep architecture between these groups is presented in Table 2. WASO was notably higher in the PLMD group, at 103 ± 86 minutes compared to 21 ± 15 minutes (P = .03) (Table 2). In addition, the average SE of the PLMD group was significantly decreased at 73 ± 18% versus 89 ± 10% in the m-AD group (P = .04). Arousal index was higher in the PLMD group than the m-AD group, 31 ± 11 versus 14 ± 6 arousals per hour during TST, respectively, (P < .01). AHI was within normal limits in the m-AD and PLMD groups.

Limb Movements in Patients With AD and Elevated LMI Versus Patients With PLMD

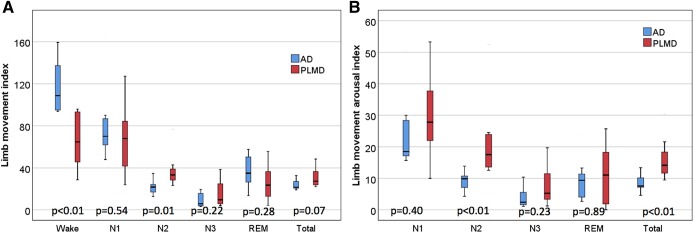

As described in detail in Table 2, total limb movements were markedly elevated in both groups, with LMI of 24 ± 6 events/h in the m-AD group and 31 ± 9 in PLMD group (P = .07). Given that there was borderline significance when comparing LMI between groups, it was difficult to draw further conclusions. However, because these results were of interest, we chose to further compare data between the cohorts. These results may be limited because only 7 patients are in each group. The LMI in stage N2 sleep was significantly increased in the PLMD group (38 ± 17) as compared to the m-AD group (22 ± 7; P = .01). Notably, the m-AD group had a significantly greater limb movement index during wakefulness (118 ± 27) as compared to the PLMD group (66 ± 27; P < .01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Box plots showing temporal distribution of total limb movements and arousals for children with PLMD (n = 7) and children with m-AD with elevated limb movements (n = 7).

(A) Box plots show a significantly decreased LMI in children with PLMD during wakefulness and a significantly increased LMI during stage N2 sleep as compared to children with m-AD. (B) Box plots show significantly increased total limb movements associated with arousal indexes in children with PLMD for stage N2 sleep and total sleep as compared to children with m-AD. AD = atopic dermatitis, LMI = total limb movement index, m-AD = mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis, PLMD = periodic limb movement disorder, REM = rapid eye movement.

LMAI was elevated above normative values in both groups, at 9 ± 3 events/h in the m-AD group and 16 ± 7 events/h in the PLMD group (P < .01). The PLMD group had more arousals associated with limb movements throughout all stages of sleep, with significantly increased LMAI during stage N2 sleep (22 ± 13) as compared the m-AD group (9 ± 3; P < .01) (Figure 2). Of note, patients were not instructed to discontinue antihistamines at the time of PSG and 16 patients were taking them at the time of the study.

DISCUSSION

In a retrospective study of all children underdoing PSG at our institution, our study confirmed the presence of sleep disturbance in children with AD. No child had been referred solely for an indication of AD-induced sleep disturbance. On average, it took children with AD more time to fall asleep, there was more WASO, and SE was decreased, as compared to normative data.16–18 These results are similar to those previously found in a prospective study on pediatric patients with AD undergoing PSG in 72 children with AD and 32 control patients.10

Furthermore, our study showed that stage N1 sleep was shortened whereas stage N3 sleep was prolonged. These findings may be partially explained by increased arousal in stage N1 sleep secondary to increased scratching as compared to stage N3 sleep.19,20 However, scratching may not be the sole etiology for increased arousal in stage N1 sleep, as arousals in patients with AD are not always associated with scratching or any other definable event.4 It could be that the “hyperarousable” state of AD also contributes to poor sleep. We suggest that pruritus may provide an additional impetus for arousal in stage N1 sleep due to a decreased threshold for arousal as well as an increased prevalence of nocturnal pruritus during this sleep stage.21

Although increased sleep latency in AD has been described in some studies,10 others have noted no difference in sleep latency as compared to studies of control patients.5,8 In a recent study, actigraphy was used to assess sleep in 19 children with moderate to severe AD and it was determined that sleep latency was not increased as compared to that in control patients.8 It might be that increased sleep deprivation associated with increased AD severity may be a driving force that allows children with severe disease to fall asleep faster. We suggest that the prolonged latency associated with the current cohort may be reflective of mild disease in most patients, though our results may be confounded by difficulty falling asleep associated with the foreign environment of laboratory-based PSG. Future studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between sleep latency relative to AD severity.

In children with AD, PLMD at times can be diagnosed because of itch-induced movement of the limbs. In a previous case report, a 5-year-old child with AD was found to meet electrophysiologic criteria for periodic limb movements in sleep, although through video monitoring they determined that her movements were associated with purposeful scratching related to AD.12 The AASM defines periodic limb movements in sleep with children as (1) having a significant leg movement event and (2) with a periodic limb movement series (minimum of 4 consecutive limb movement events, period length between limb movements between 5 to 90 seconds, and leg movements on 2 different legs separated by less than 5 seconds).22 Although scratching will often meet criteria for periodic limb movements in sleep, a diagnosis of PLMD should not be given due to eczema-induced scratching events. Because many children coming for PSG will have AD, it is an important aspect of etiology to consider for sleep-disturbing limb movements. In fact, some of these children meet diagnostic criteria for PLMD. However, other causes of sleep disturbance (including concurrent sleep, medical, or psychological disorders) must be excluded in order to diagnose PLMD. AD is not currently a diagnosis that is suggested to meet exclusion criteria. In order to prevent incorrectly diagnosing AD in patients with PLMD, we suggest careful evaluation of medical history, PSG parameters, and accompanying video. Additionally, periodic limb movements in sleep might also be increased regardless of scratching in patients with AD. We suggest that the sensory input from AD may trigger periodic limb movements in sleep. Currently, the increased occurrence of periodic limb movements in sleep with conditions such as OSA and narcolepsy is not well understood and there may be a bidirectional relationship for sleep disturbance and AD.23

In comparing limb movements in patients with m-AD and PLMD, several patterns were observed. Limb movements during periods of wake were significantly increased in AD. Although limb movements during sleep in a subset of patients with AD were elevated to the same extent as patients with PLMD. Children with milder AD had significantly fewer arousals associated with these movements. Total limb movements and arousals from limb movements were consistently increased during stage N2 sleep in children with PLMD as compared to children with m-AD. In addition to analyzing limb movements during wake if possible, we suggest that assessment of stage N2 sleep for both total limb movements and associated arousals may allow for distinction between the two conditions. It is important to be able to differentiate these patients because patients with AD may benefit from melatonin,24 whereas those with PLMD may need iron or another medication.

Perhaps what is most striking is the significantly increased number of limb movements during wakefulness in children with m-AD as compared to children with PLMD. These results suggest that children with m-AD may meet diagnostic criteria for restless legs syndrome (RLS) as defined by a patient’s irresistible urge to move the legs accompanied by or perceived to be caused by uncomfortable or unpleasant sensations in the legs.22 Currently, RLS criteria are applicable to pediatric patients with specific matters additionally made applicable to children. Given that the diagnostic criterion exclude patients that have another condition that solely accounts for symptoms, this likely applies to patients who have an urge to move due to pruritus. We hypothesize that the pruritus associated with AD (or other conditions) may be a mimic of pediatric RLS. Interestingly, no patients in the AD cohort with elevated limb movements had a diagnosis of RLS, as defined by ICD-9 codes 333.94 and G25.81. Future large-scale studies are needed to assess the symptoms of RLS in children and to determine whether AD may be a potential mimicker.

One of the notable strengths of this study was the inclusion of overnight PSG data, whereas much of the current literature surrounding quality of sleep in AD is limited to actigraphy. In addition, we utilized strict exclusion criteria to minimize alternate causes of sleep disruption in the cohort (Figure 1). Because many children undergoing PSG at a tertiary center have significant comorbidities, this was important to isolate the effect of AD. The most apparent limitation of the study was the lack of a control group with in-house PSG. Comparing study data to published normative values is not ideal, as PSG techniques and scoring can vary between laboratories. Also, because our patients had mild AD and not as many limb movements as compared to the patients with PLMD, we found that sleep was more efficient in patients with AD. Lastly, due to the composition of our cohort our observations of sleep disturbance in AD were limited to mild disease, which may not have been particularly active as AD is a condition that tends to flare and then have lower levels of disease activity. Despite the profound impact of AD on sleep, this speaks to the lack of referrals of patients with AD to sleep medicine.

We recommend that presence of AD should be considered before making a diagnosis of PLMD. Adequate treatment of AD will give these patients a better prognosis. Future studies comparing patients with severe AD to patients with PLMD may provide further insight into the extent at which limb movements in AD effect arousals and other sleep parameters.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AASM

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- AI

arousal index

- LMAI

limb movement arousal index

- LMI

limb movement index

- m-AD

mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis

- PLMD

periodic limb movement disorder

- PSG

polysomnography

- R

REM

- TST

total sleep time

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

REFERENCES

- 1.Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl. 1):8–16. doi: 10.1159/000370220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishbein AB, Vitaterna O, Haugh IM, et al. Nocturnal eczema: Review of sleep and circadian rhythms in children with atopic dermatitis and future research directions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren M-M. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):607–611. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuveni H, Chapnick G, Tal A, Tarasiuk A. Sleep fragmentation in children with atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):249–253. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender BG, Leung SB, Leung DY. Actigraphy assessment of sleep disturbance in patients with atopic dermatitis: an objective life quality measure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(3):598–602. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bender BG, Ballard R, Canono B, Murphy JR, Leung DY. Disease severity, scratching, and sleep quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stores G, Burrows A, Crawford C. Physiological sleep disturbance in children with atopic dermatitis: a case control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(4):264–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camfferman D, Kennedy JD, Gold M, Martin AJ, Lushington K. Eczema and sleep and its relationship to daytime functioning in children. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(6):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang YS, Chou YT, Lee JH, et al. Atopic dermatitis, melatonin, and sleep disturbance. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e397–e405. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(5):476–486. doi: 10.1111/pai.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DelRosso L, Hoque R. Eczema: a diagnostic consideration for persistent nocturnal arousals. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(4):459–460. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicek D, Halisdemir N, Dertioglu SB, Berilgen MS, Ozel S, Colak C. Increased frequency of restless legs syndrome in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(5):469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.0. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholle S, Wiater A, Scholle HC. Normative values of polysomnographic parameters in childhood and adolescence: cardiorespiratory parameters. Sleep Med. 2011;12(10):988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholle S, Wiater A, Scholle HC. Normative values of polysomnographic parameters in childhood and adolescence: arousal events. Sleep Med. 2012;13(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholle S, Beyer U, Bernhard M, et al. Normative values of polysomnographic parameters in childhood and adolescence: quantitative sleep parameters. Sleep Med. 2011;12(6):542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savin J, Paterson W, Oswald I, Adam K. Further studies of scratching during sleep. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93(3):297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb06495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monti JM, Vignale R, Monti D. Sleep and nighttime pruritus in children with atopic dermatitis. Sleep. 1989;12(4):309–314. doi: 10.1093/sleep/12.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavery MJ, Stull C, Kinney MO, Yosipovitch G. Nocturnal pruritus: the battle for a peaceful night’s sleep. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):425. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpy M. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. In Chokroverty S, ed. Sleep Disorders Medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 2017:47–484. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis: a 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(4):1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang YS, Lin MH, Lee JH, et al. Melatonin supplementation for children with atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):35–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]