Abstract

Buprofezin, a chitin synthesis inhibitor that can be used for the control of hemipteran pests, especially melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. The impact of low lethal concentrations of buprofezin on the biological parameters and expression profile of CHS1 gene were estimated for two successive generations of A. gossypii. The present result shows that the LC15 and LC30 of buprofezin significantly decreased the fecundity and longevity of both generations. Exposure of F0 individuals to both concentrations delay the developmental period in F1. Furthermore, the survival rate, intrinsic rate of increase (r), finite rate of increase (λ), and net reproductive rate (R0) were reduced significantly in progeny generation at both concentrations. However, the reduction in gross reproductive rate (GRR) was observed only at LC30. Although, the mean generation time (T) prolonged substantially at LC30. Additionally, expression of the CHS1 gene was significantly increased in F0 adults. Significant increase in the relative abundance of CHS1 mRNA transcript was also observed at the juvenile and adult stages of F1 generation following exposure to LC15 and LC30. Therefore, our results show that buprofezin could affect the biological traits by diminishing the chitin contents owing to the inhibition of chitin synthase activity in the succeeding generation of melon aphid.

Subject terms: Entomology, Transcription

Introduction

The melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a cosmopolitan sap-sucking pest that infests plants of Cucurbitaceae family worldwide1,2. A. gossypii cause damage to plants through direct feeding by curling and deforming the young leaves and twigs3. Moreover, melon aphids affect plants indirectly by transmitting plant viruses such as Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV)2 and by secreting honeydew, which causes the growth of black sooty mold4. The melon aphid transmits 76 viral diseases across 900 known host plants5. Different tactics have been used to control A. gossypii, but still, pesticides application remains the primary tool of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs against this pest6. However, the widespread use of insecticides such as organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids has led to the development of resistance in aphids throughout the world7–9. Notably, previous studies stated that A. gossypii show higher resistance against neonicotinoid insecticides7,8. The increased resistance of A. gossypii against imidacloprid has been documented in China10.

Chitin is a polymer of N-acetyl-b-D-glucosamine which are crucial for insects in maintaining shape, providing strength and protection11,12. Chitin biosynthesis pathway is catalyzed by two chitin synthase enzymes encoded by two genes, i.e., Chitin synthase 1 (CHS1) and chitin synthase 2 (CHS2) having a significant role in insect growth and development11,13. CHS1 is expressed in the exoskeleton structures encoding the isoform of enzymes that are responsible for the catalysis of chitin production in the cuticle14,15. CHS2 is mainly present in the midgut epithelial cells encoding enzymes to synthesize chitin in the insect midgut16. CHS1 gene has been cloned in many insects such as brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida17, soybean aphid, Aphis glycines18, Bactrocera dorsalis19, Plutella xylostella20, Nilaparvata lugens21 and Locusta migratoria22. Despite that, due to the lacking of the peritrophic membrane, CHS2 was not present in some insect pests12,17,18. The molting process accompanied by the formation of the cuticle is crucial for insect growth; therefore, suppression of chitin biosynthesis gives us an ideal platform for insect control17,18.

Insect growth regulator23, a class of insecticide having low vertebrate toxicity with a unique mode of action from currently used broad-spectrum neurotoxic insecticides24. Many IGRs have shown high efficiency against various insect species, as it disrupts the molting process of insect pest during developmental stages24, e.g. in the orders of Hemiptera25, Lepidoptera26, and Diptera27. Buprofezin is a chitin synthesis inhibitor prepared by Nihon-Nohyaku and is widely used against several sucking pests with very low risk to the environment25,28–32. Buprofezin is considered to be safe for humans owing to the absence of chitin biosynthesis pathway in vertebrates18. It has also been stated harmless for the natural enemies under field contexts32. Comprehensive knowledge about the exact mode of action of buprofezin is still lacking. However, initially it suppresses the chitin biosynthesis during molting and causes immature death during cuticle shedding33. Moreover, it disturbs the oviposition, egg fertility, and reduces fecundity after adult females were treated25,33.

Owing to the misapplication of pesticides and presence of their residues after degradation in fields34, the exposure of arthropods to low concentrations of these chemicals frequently occurrs, resulting in sublethal effects causing various physiological and behavioral disruptions in surviving organisms35 such as life span36, developmental rate37, fecundity38, feeding behavior39 and also alter the insect population dynamics40. Furthermore, such exposure to pesticides may also cause transgenerational effects, i.e., indirectly affecting the descendants41. Comprehensive studies about the impact of low concentration of insecticides have great importance to increase their rational application against target pests29,30. Hence, several studies reported the effects of buprofezin at sublethal or low lethal concentrations on insect pests25,28,29. Studies of these potential sublethal effects in-depth would help to improve the IPM programs.

These sublethal effects are usually detrimental to exposed individuals35. However, several studies have reported stimulatory impact when exposed to low or sublethal concentrations42–45. The stimulatory effects (known as hormesis) is a phenomenon that is encouraged by low dose while inhibited by high dose exposure of insecticides46. Several studies reported these hormetic effects on insect pests following exposure to insecticides, e.g., low dose of imidacloprid cause hormesis effect in Myzus persicae (Sulzer)47 and Aphis glycines (Matsumura)48. Recently, transgenerational hormesis has been observed in A. gossypii when exposed to nitenpyram at low lethal and sublethal concentration45. Besides, previous studies have also shown the insecticide stimulatory effect in A. gossypii at low doses of pirimicarb and flonicamid49.

A two-sex life table is widely used for investigating multiple sublethal effects of insecticides on insects, as it allows us to gain comprehensive knowledge that could be underrated at the individual level50–53. In-depth knowledge about the impact of low lethal concentrations of buprofezin on the biology of A. gossypii is still lacking. To address these gaps, we use age-stage life table parameters to appraise the sublethal and transgenerational effects of buprofezin on biological characteristics of A. gossypii. Moreover, to gain potential knowledge on impact of buprofezin on A. gossypii, we analyzed the expression profile of chitin synthase 1 gene (CHS1) at low dose exposure.

Results

Toxicity of buprofezin on melon aphids

Buprofezin toxicity against A. gossypii was determined following 48 and 72 h exposure (Table 1). The estimated value of LC15 was 1.125 mg L−1 and LC30 was 2.888 mg L−1, while LC50 was 7.586 mg L−1 after 48 h exposure of buprofezin. Similarly, the LC15, LC30, and LC50 were 0.435 mg L−1, 0.898 mg L−1 and 1.886 mg L−1 respectively after 72 h exposure. The toxicity of buprofezin was higher at 72 h exposure. The low lethal concentrations LC15 and LC30 were selected to evaluate the sublethal effects of the buprofezin on the life history traits and expression profile of chitin synthase 1 gene (CHS1) in melon aphid following 72 h exposure.

Table 1.

Toxicity of buprofezin against A. gossypii after 48 and 72 h exposure. aStandard error; bConfidence limits; cChi-square values and degrees of freedom.

| Treatments | Slope ± SEa | LC15 mg L−1 (95% CLb) | LC30 mg L−1 (95% CLb) | LC50 mg L−1 (95% CLb) | χ2 (df)c | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buprofezin (48 h) | 1.251 ± 0.165 | 1.125 (0.748 to 1.504) | 2.888 (2.231 to 3.804) | 7.586 (5.493 to 12.232) | 3.358 (16) | 0.999 |

| Buprofezin (72 h) | 1.627 ± 0.149 | 0.435 (0.302 to 0.571) | 0.898 (0.702 to 1.098) | 1.886 (1.570 to 2.274) | 11.113 (16) | 0.802 |

Sublethal effects of buprofezin on parental aphids (F0)

LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin have significant effects on parental A. gossypii following 72 h exposure. Both concentrations (LC15 and LC30) significantly decreased the longevity (F = 103.22; df = 2, 25; P < 0.001) and fecundity (F = 160.40; df = 2, 25; P < 0.001) of the exposed F0 population. Furthermore, LC30 concentration of buprofezin showed a stronger effect compared to LC15 and the control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean ( ± SE) developmental times (d) of various life stages of F1 generation A. gossypii produced from parents (F0) and longevity (d) and fecundity (d) of F0 generation treated with LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin for 72 h compared to the untreated control.

| Treatments | 1st instar | 2nd instar | 3rd instar | 4th instar | Pre-adult | Adult Longevity F1 | Adult Fecundity F1 | Adult Longevity F0 | Adult Fecundity F0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.85 ± 0.07b | 1.48 ± 0.07b | 1.32 ± 0.06b | 1.03 ± 0.02c | 5.68 ± 0.06c | 25.38 ± 0.68a | 35.17 ± 0.23a | 21.16 ± 0.61a | 28.86 ± 0.82a |

| LC15 | 1.97 ± 0.05b | 1.62 ± 0.06b | 1.47 ± 0.07b | 1.28 ± 0.05b | 6.33 ± 0.07b | 18.40 ± 0.48b | 28.30 ± 0.81b | 14.03 ± 0.61b | 18.03 ± 0.84b |

| LC30 | 2.17 ± 0.04a | 1.98 ± 0.06a | 1.88 ± 0.07a | 1.82 ± 0.07a | 7.85 ± 0.05a | 10.83 ± 0.55c | 12.27 ± 0.25c | 8.30 ± 0.67c | 9.01 ± 0.66c |

Different letters within the same column represent significant differences at P < 0.05 level (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD tests).

Transgenerational sublethal effects of buprofezin on progeny aphids (F1)

Impact of low lethal concentrations of buprofezin on progeny A. gossypii (F1) were determined (Table 2). The mean longevity (F = 153.82; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) and fecundity (F = 527.07; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) of F1 generation significantly decreased for LC30 and LC15. Furthermore, after exposure of F0 individuals to the LC30 of buprofezin, the developmental period of 1st instar (F = 7.58; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) and 2nd instar (F = 14.19; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) of F1 individuals were significantly prolonged. Similarly the duration of 3rd instar (F = 16.31; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) and 4th instar (F = 48.43; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) also increased significantly at LC30 of buprofezin. The total duration of pre-adult period (F = 273.70; df = 2, 178; P < 0.001) significantly increased in the offspring of F0 generation after treated by both concentrations of buprofezin compared to the control.

Paired bootstrap technique was applied to determine the transgenerational impact of buprofezin (LC15 and LC30) on population growth using TWOSEX MS chart program54. The population parameters of F1 individuals, such as λ, r, R0, and GRR were reduced at LC30 concentration. Obvious increase was noted for the mean generation time (T) at LC30. However, no effects were observed for the LC15 of buprofezin (Table 3). The age-stage specific survival rate (sxj) curves indicated variations in the developmental rates occurring among juvenile stages. Moreover, overlapping between different immature stages were shown in control (Fig. 1A), LC15 (Fig. 1B) and LC30 concentration of buprofezin (Fig. 1C). The adult survival rates differed among the buprofezin treatments (LC15 and LC30) and the control. Furthermore, the declined survival rate of melon aphid adults for LC30 concentration was recorded at the 12th day (Fig. 1C) and the 16th day was recorded for LC15 concentration (Fig. 1B), while the decline survival rate of melon aphid adults for the control was recorded at the 23rd day (Fig. 1A).

Table 3.

Transgenerational effects of buprofezin on population parameters of the F1 generation of A. gossypii whose parents (F0 generation) were treated with LC15 and LC30 concentrations compared to untreated control. r: intrinsic rate of increase (d−1), λ: finite rate of increase (d−1), R0: net reproductive rate (offspring/individual), T: mean generation time (d), GRR: gross reproductive rate were calculated using 100,000 bootstraps resampling.

| Parameters | Control (Mean ± SE) | LC15 (Mean ± SE) | P value | Control (Mean ± SE) | LC30 (Mean ± SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.302 ± 0.0054a | 0.275 ± 0.0050b | 0.0002 | 0.302 ± 5.413a | 0.196 ± 0.0030b | <0.001 |

| λ | 1.353 ± 0.0073a | 1.317 ± 0.0066b | 0.0002 | 1.353 ± 7.325a | 1.217 ± 0.0037b | <0.001 |

| R0 | 35.166 ± 0.302a | 28.236 ± 0.820b | <0.001 | 35.166 ± 0.302a | 12.266 ± 0.256b | <0.001 |

| T | 11.771 ± 0.217a | 12.125 ± 0.212a | 0.243 | 11.771 ± 0.217b | 12.741 ± 0.223a | 0.0019 |

| GRR | 42.412 ± 0.923a | 40.529 ± 1.359a | 0.221 | 42.412 ± 0.923a | 21.137 ± 0.983b | <0.001 |

Different letters within the same row show significant differences between control and buprofezin concentration groups (at the P < 0.05 level, paired bootstrap test using TWOSEX MS chart program).

Figure 1.

Age-stage specific survival rate (sxj) of A. gossypii of the F1 generation produced from parents (F0) under control condition (A), treated with LC15 (B), and treated with LC30 (C) of buprofezin.

The age-specific survival rate (lx), age-specific fecundity (mx), and the age-specific maternity (lxmx) for the treated and control A. gossypii are presented in Fig. 2. Compared to control treatment, the lx value for LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin declined more rapidly. The population started to decrease after 23 days in control (Fig. 2A), whereas it declined after 16 days and 12 days in the LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin respectively (Fig. 2B,C).

Figure 2.

Age-specific survival rate (lx), age-specific fecundity (mx) and age-specific maternity (lxmx) of control (A) and A. gossypii individuals of F1 generation descending from F0 individuals exposed to the LC15 (B) and LC30 (C) concentrations of buprofezin.

The mx and lxmx values of the exposed A. gossypii were lower as compared to control (Fig. 2).

The age-stage reproductive values (vxj) of buprofezin treated adult aphids indicated that the vxj of LC15 (Fig. 3B) and LC30 (Fig. 3C) concentrations of buprofezin was lower in contrast to the control individual (Fig. 3A). The vxj value of LC15 (6.80 at the age of the 6th day) and LC30 concentrations (4.9 at the age of the 7th day) of buprofezin was lower compared to the control aphids (8 at the age of the 5th day) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the duration of F1 aphid’s reproduction was different after F0 generation exposure to buprofezin (LC15 and LC30) compared to the control. The vxj value more than 4 was found for 17 days in the control group of melon aphid (Fig. 3A), while it was reported 14 and 7 days for LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin, respectively (Fig. 3B,C). The age-stage-specific life expectancy (exj) of buprofezin treated A. gossypii (LC15 and LC30) was lower as compared to the untreated control group (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Age-stage reproductive value (vxj) of A. gossypii individuals of the F1 generation produced from parents (F0) under control conditions (A), treated with LC15 (B) and treated with LC30 (C) concentration of buprofezin.

Figure 4.

Age-stage specific survival rate (exj) of A. gossypii descending from parents (F0) under control condition (A), treated with LC15 (B), and treated with LC30 (C) concentrations of buprofezin.

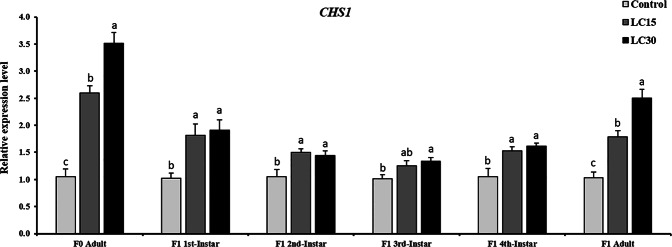

Sublethal effects of buprofezin on the expression profile of CHS1 gene in melon aphid

Expression profile of CHS1 gene in melon aphids was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) during F0 adult and all developmental stages as well as newly emerged adult F1 individuals. The results indicated that the mRNA level was up-regulated in F0 adults and almost all stages of F1 melon aphids at LC15 and LC30 of buprofezin, after the exposure of parent generation (F0) for 72 h (Fig. 5). However, CHS1 gene was relatively highly expressed in F0 adults treated with LC30 (3.51-fold), while it was 2.59-fold increase for the case of LC15 concentration of buprofezin. In the case of F1 generation descending from the treated parent (F0), CHS1 gene was constantly expressed in aphids from 1st instar to the newly emerged adult aphid. The mRNA level of CHS1 was highly expressed in the 1st instar (1.91-fold) and 2nd instar nymph (1.44-fold) following exposure to buprofezin LC30. For LC15 - treated group, the relative expression was 1.81- and 1.50-fold for the 1st and 2nd instar nymph respectively, compared to the control. The CHS1 gene was abundantly expressed 1.33-fold in 3rd instar and 1.60-fold in the 4th instar nymph after exposure to LC30, while they showed 1.24- and 1.53-fold increase for LC15 concentration of buprofezin. In F1 newly emerged adults, 2.50- and 1.78-fold abundance of the CHS1 were observed at LC30 and LC15 concentrations of buprofezin, respectively (Fig. 5). The transcriptional level of CHS1 gene increased 2.80- and 1.90-fold in parental aphids (F0) following 48 h exposure to the LC30 and LC15 concentrations of buprofezin respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). While no effects were observed in the progeny generation (F1). No significant increase was noted for the CHS1 gene transcription when melon aphids were treated to the two low lethal concentrations of buprofezin for 24 h (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 5.

Relative expression levels of the chitin synthase 1 gene (CHS1) in F0 adults and in all developmental stages along with newly emerged adult melon aphid of F1 generation descending from the parent (F0) exposed to the LC15 and LC30 concentrations of buprofezin for 72 h. The relative expression level is expressed as the mean (±SE) with the control as the calibrator. Different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 level (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD tests).

Discussion

The impact of buprofezin on the biological traits and expression profile of chitin synthase 1 (CHS1) gene of melon aphid were investigated following exposure to low lethal concentrations of this pesticide. Sublethal effects of buprofezin, e.g. reduced longevity and fertility have been reported in various insect pests, e.g. Sogatella furcifera Horvath (Hemiptera: Delphacidae)29,30, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)25, Eretmocerus mundus Mercet (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae)25, Encarsia inaron (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae)28. In this study, the impact of buprofezin at low lethal concentrations were examined demographically among two subsequent generations of A. gossypii. The results showed a decrease in longevity and fecundity of A. gossypii at LC15, and even more markedly at LC30 concentration of buprofezin in the progeny generation individuals. Similar effects were reported in the previous studies where the fecundity and longevity of S. furcifera females significantly reduced at sublethal doses of buprofezin29,30. The adult longevity and fecundity were decreased considerably when A. gossypii was treated to the LC10 and LC40 of cycloxaprid55. Additionally, low fertility has also been documented in A. gossypii56, B. brassicae57, and Diaphorina citri58 at sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid. Buprofezin inhibits the prostaglandin biosynthesis in N. lugens when treated to the sublethal concentrations resulting in spawning suppression59. Similar results have also been reported for a low dose of pyriproxyfen in Aphis glycines Matsumura (Hemiptera: Aphididae)60, P. xylostella41 and Choristoneura rosaceana61 (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)62. These studies suggested that low lethal or sublethal concentrations of insecticides, including IGRs, adversely affect the longevity as well as the fecundity of exposed insect pests, which can be widely diffused in various IPM programs.

Transgenerational effects on the offspring of treated A. gossypii (F0) were also found. The longevity and fecundity of F1 individuals were decreased significantly at LC15 and LC30 concentrations, while the pre-adult period was increased. These effects are related to the reductions of F1 demographical parameters. We had shown the data that the demographical parameters, e.g. r, λ, and R0 were reduced significantly in F1 generation when its parents (F0) were subjected to LC15 and LC30 of buprofezin compared to the control; however, such negative impact on gross reproduction rate (GRR) was only evident at LC30 concentration of buprofezin. Previously, similar effects were documented on the offspring of white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera29, cotton aphid, A. gossypii63, and brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus64 when subjected to the sublethal concentrations of buprofezin, sulfoxaflor, and thiamethoxam.

The analysis of the plotted curves for the sxj, lx, mx, lxmx, and exj showed the adverse effects of buprofezin on the population growth parameters of A. gossypii. The vxj stated that the reproduction duration of melon aphids was negatively affected when exposed to low doses buprofezin. The pre-adult period and mean generation time (T) were increased due to different physical and chemical processes when treated with buprofezin. Similar effects at the demographical level have been presented in various other reports29,30,65,66. Previous reports suggested that exposure to sublethal concentrations of buprofezin can suppress the population growth of S. furcifera via impact on their survival and reproduction29,30. Additionally, adverse effects at the demographical level have been reported in melon aphid at 25 and 100 ppm of cucurbitacin B65. Moreover, sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid and pirimicarb decreased the longevity and population growth of A gossypii67. Soybean aphid also showed been reduced population growth when they were exposed to sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid48.

Chitin synthase 1 (CHS1) is crucial for the chitin synthesis11, which has been studied in various insects including soybean aphid, Aphis glycines, and brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida17,18. In this study, the relative transcript level of CHS1 gene was up-regulated in the F0 adult and in all nymphal stages of F1 generation when exposed to LC15 and LC30 of buprofezin for 72 h. A previous study documented similar results for the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Horváth) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) when exposed to the LC10 and LC25 (0.10 and 0.28 mg/L) of buprofezin30. Additionally, the diflubenzuron exposure in insects including Anopheles quadrimaculatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae), Aphis glycines Matsumura (Hemiptera: Aphididae), Panonychus citri McGregor (Acari: Tetranychidae), and Toxoptera citricida Kirkaldy (Hemiptera: Aphididae) resulted in increased expression of CHS1 gene, which may be linked to increased mortality17,18,68,69. As the IGRs including buprofezin causes reduction in chitin content owing to the inhibition of chitin synthase activity in the exposed insect pests, which are translated into abortive molting, reduce longevity, decrease fecundity, and direct mortality17,18,30,68,69. In our investigations, the melon aphid population dynamics were reduced owing to the low lethal concentrations of buprofezin, suggesting their effectiveness against this insect pests. Moreover, the increasing abundance of CHS1 mRNA transcript may result from a regulatory feedback mechanism that compensates the CHS enzyme activity inhibited by buprofezin. The compensation mechanism that is proposed through overexpression of CHS1 gene translated into overproduction of the CHS1 protein. However, owing to the buprofezin exposure, the potential overproduction of CHS1 protein would be insufficient to maintain a vital level of CHS catalytic activity. Finally, the compensation mechanism failed to restore the enzymatic activity in the presence of buprofezin translated into reduced chitin production and causes the insect mortality.

In contrast to all these results, several studies documented no effect of insect growth regulator (e.g., diflubenzuron) on CHS1 gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster and Tribolium castaneum70,71. Therefore, future work needed to understand the biological significance of CHS1 gene comprehensively and as well as the relevant molecular mechanisms in the buprofezin exposed insects.

In conclusion, the LC15 and LC30 were used to understand the consequences of buprofezin on the biological traits and as well as their impact on the expression level of CHS1 gene in A. gosspii for over two successive generations. Results indicated a significant reduction of parental aphid’s longevity and fertility when treated to the LC15 and LC30 of buprofezin. Moreover, both concentrations of buprofezin delay the aphid developmental stage and suppress the population growth of the progeny generation (F1). Also, the CHS1 gene mRNA abundance was increased significantly at both concentrations following 72 h exposure. However, the effects observed from confined experimental scales may not translate into population effects under field contexts. Therefore, further investigation is necessary under field conditions to fully understand the potential of buprofezin’s integration into an optimized IPM strategy to control this insect pest.

Materials and Methods

Insects and insecticide

Melon aphid was originally collected from melon plants at Weifang District, Shandong Province, China. These insects were reared on fresh cucumber plants and were maintained under standard laboratory conditions with a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity (RH) and a 16:8 h light/dark photoperiod. Buprofezin with 97.4%, of active ingredient, was obtained from Jiangsu Anpon Electrochemical Co., Ltd. China.

Toxicity of buprofezin against Aphis gossypii

Toxicity of buprofezin was tested on A. gossypii using widely applied leaf dip bioassay procedure48,66,72,73. To ensure that all melon aphids were of same age and life instar, about 450 melon aphid adults were introduced on fresh cucumber plants. All adult aphids were removed after 24 hours while the offspring were allowed to grow on plants for eight days without any insecticide application. At this time, the newly-born nymphs passed all developmental stages and became apterous adults65,66.

The stock solution of buprofezin (active ingredient 97.4%) was prepared in acetone. The concentrations were further diluted with distilled water containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100 to obtain six concentrations (8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5 and 0.25 mg L−1) for bioassays. Fresh leaf discs of cucumber plants were dipped for 15 s in the buprofezin solutions. After air drying, discs of cucumber plants were placed on agar bed (2%) in the 12-well tissue culture plate. Adult aphids were inoculated on the treated disc using a soft brush. The plates were covered with Parafilm (Chicago, USA). Each treatment has three replications, and 20–30 aphids per replicate were used in bioassay. Distilled water containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100 was used as a control. All plates were placed in standard laboratory conditions with a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C, RH of 75% and a 16:8 h light/dark cycle (L:D). After 48 and 72 h exposures, aphid’s mortality was checked. Aphids were considered dead if not show any movement after pushing gently48,74. Mortality of controlled aphids was less than 10%. PoloPlus 2.00 was used to determine the LC15, LC30 and LC50 of buprofezin.

Sublethal effects of buprofezin on F0 melon aphid

The life history traits of parental A. gossypii (F0) were investigated following the previously described methods with slight modifications65,66. The stock solution of buprofezin was prepared using acetone. The tested concentrations of buprofezin (LC15 and LC30) was prepared in distilled water containing 0.05% triton X-100. The low lethal concentrations of buprofezin (LC15 and LC30) were selected to determine their impact on melon aphids, as most of the pesticides were degraded after initial application by various factors34,75. Insecticide exposure was carried out, as discussed above. After 72 h exposure, sixty live and healthy aphids were collected from buprofezin treatments (LC15, LC30) and control. The apterous melon aphid adults collected from LC15, LC30 and control were inoculated on fresh leaf discs individually65,66. Placed the treated discs on agar bed (2%) in the 12-well tissue culture plate. Parafilm (Chicago, USA) was used to cover the plate to prevent aphids escape. Fresh leaf discs were replaced throughout the experiment at every 3rd day. All plates from buprofezin treatments (LC15, LC30) and control were placed under laboratory conditions as mentioned above. Longevity, as well as fecundity of A. gossypii, were noted daily till death.

Transgenerational effects of buprofezin on F1Aphis gossypii

Impact of buprofezin at low lethal concentrations on the progeny generation (F1) of melon aphids were evaluated using the same method and treatments as discussed previously. The newly-born nymphs were individually retained on each insecticide-free cucumber leaf disc, and they were used as F1 generation of melon aphid. Sixty aphids were used for each of the treatment (LC15, LC30) and control. Each aphid was considered as a single replication. The number of offspring were counted on a daily basis until the death of the adults.

Impact of buprofezin on chitin synthase 1 gene expression at low lethal concentrations in melon aphid

Impact of buprofezin exposure on chitin synthase 1 gene expression in melon aphid was evaluated using the same experimental setup as described above. Survived healthy melon aphid adults were collected after 24, 48, and 72 h exposure and stored in −80 °C as F0 generation. For F1 generation, exposed aphids collected from LC15, LC30 and control were transferred to new 20 mm diameter insecticide-free cucumber leaf discs. Aphids were collected at 4 developmental and newly emerged adult stages from both buprofezin treatments and control representing F1 generation. Total RNA was isolated from the exposed A. gossypii using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. NAS-99 spectrophotometer (ACTGene) was used to analyze the RNA purity. Total RNA (1 μg) was used to synthesize the cDNA using the PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit with the gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). Real-time qPCR was performed using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, Dalian, China). Primers for qPCR were synthesized using PRIMER 3.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/) based on the conserved sequence of Soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) CH1 gene (GenBank No. JQ246352.1) (Table 4). Elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α), beta-actin (β-ACT) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal reference genes76. The reaction volume for qPCR was 20 μL including 10 μL of the SYBR®Premix Ex Taq, 1 μL of cDNA template, 0.4 μL of each primer, 0.4 μL of ROX Reference Dye II, and 7.8 μL of RNase-free water. The thermal cycling condition was initiated at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s, and a dissociation stage at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min and 95 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C for 15 s. Three independent biological replicates with three technical replications were carried out for each qRT-PCR. To check the amplification efficiencies and cycle threshold (Ct), the standard curve was established with serial dilutions of cDNA (1, 1/10, 1/100, 1/1000, 1/10,000, and 1/100,000). Quantification of gene transcription was calculated using 2−∆∆Ct method77.

Table 4.

Primer sequences for chitin synthase 1 (CHS1) and internal control genes used to determine the expression profile in A. gossypii following exposure to buprofezin.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| CHS1-F | ATTGCGTCACGATGATCCTT | qRT-PCR |

| CHS1-R | TGGTCGCTAGACGTTCACAC | qRT-PCR |

| EF1α-F | GAAGCCTGGTATGGTTGTCGT | qRT-PCR |

| EF1α-R | GGGTGGGTTGTTCTTTGTG | qRT-PCR |

| β-Actin-F | GGGAGTCATGGTTGGTATGG | qRT-PCR |

| β-Actin-R | TCCATATCGTCCCAGTTGGT | qRT-PCR |

| GAPDH-F | AACAGTTTTTTGAGTGGCGGT | qRT-PCR |

| GAPDH-R | TGGTGTCAACTTGGATGCGTA | qRT-PCR |

Data analysis

The LC15, LC30 and LC50 of buprofezin were analyzed using a log-probit model78 as commonly used in various studies42,48. The demographical (r, λ, R0, T, and GRR) and basic life table parameters (sxj, vxj, lx, mx, lxmx, and exj) were calculated using TWOSEX-MSChart program54,79,80. The intrinsic rate of increase (r) is classified as the population growth rate when the time advances infinity and population attains the stable age-stage distribution. The population will rise at the rate of er per time unit. It was calculated using eq. 1:

| 1 |

The finite rate of increase (λ) is defined as the population growth rate as the time approaches infinity and population attains the stable age stage distribution. It was calculated using Eq. 2:

| 2 |

The net reproductive rate (R0) is classified as the total fecundity produce by a common insect pest during the whole life. It was calculated using Eq. 3:

| 3 |

The mean generation time (T) is the duration of time that is needed by a population to enhance to R0-fold of its size as time advances infinity and the population calms down to a persistent age-stage distribution. It was measured using Eq. 4:

| 4 |

The gross reproduction rate (GRR) was measured using Eq. 5:

| 5 |

The age-specific survival rate (lx) was measured using Eq. 6:

| 6 |

where m is the number of stages. Age-specific fecundity (mx) was measured through Eq. 7:

| 7 |

where sxj is showing the expected survival rate of a newly-born nymph to age x and stage j. The exj of an insect of age x and stage y showing the expected time duration to live. It was measured by Eq. 8:

| 8 |

Where s′ij is the probability of an insect of age x and stage y will endure to age i and stage j. The age-stage reproductive value (vxj) is classified as the expectation of an insect of age x and stage y to the future offspring. It was measured using Eq. 9:

| 9 |

Population parameters were calculated and compared through paired bootstrap test81 using TWOSEX-MSChart with 100,000 replicates53,82. The results related to fecundity, longevity, developmental periods and CHS1 expression of A. gossypii were calculated by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test (P < 0.05) (IBM, SPSS Statistics).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0200500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31272077) to F.U., H.G., H.K.Y., W.X., D.Q., X.G. and D.S.

Author Contributions

F.U. and D.S. designed the experiment. F.U. and H.G. performed the experiments. F.U., H.G., W.X. and D.Q. collected the insects. F.U., H.G. and H.K.Y. analyzed the data. F.U., H.G., N.D., K.T. and P.H. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. D.S. and X.G. Contributed to the reagents/materials.

Data Availability

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Files). Supplementary Table S1: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to control solution. Supplementary Table S2: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to LC15 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S3: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to LC30 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S4: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by untreated adult A. gossypii. Supplementary Table S5: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by parental A. gossypii treated with LC15 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S6: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by parental A. gossypii treated with LC30 of buprofezin.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/20/2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48199-w.

References

- 1.Blackman, R. L. & Eastop, V. F. Aphids on the world’s herbaceous plants and shrubs, 2 volume set. (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

- 2.Van Emden, H. F. & Harrington, R. Aphids as crop pests. (Cabi, 2017).

- 3.Andrews M, Callaghan A, Field L, Williamson M, Moores G. Identification of mutations conferring insecticide-insensitive AChE in the cotton-melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:555–561. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson R, Croft P. Strategies for the control of Aphis gossypii Glover (Hom.: Aphididae) with Aphidius colemani Viereck (Hym.: Braconidae) in protected cucumbers. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 1998;8:377–387. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackman, R. L. & Eastop, V. F. Aphids on the world’s crops: an identification and information guide. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2000).

- 6.Shrestha RB, Parajulee MN. Potential cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii, population suppression by arthropod predators in upland cotton. Insect Sci. 2013;20:778–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herron GA, Powis K, Rophail J. Insecticide resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae), a serious threat to Australian cotton. Aust J Entomol. 2001;40:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo HN, An JJ, Park SE, Kim JI, Kim GH. Regional susceptibilities to 12 insecticides of melon and cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and a point mutation associated with imidacloprid resistance. Crop Prot. 2014;55:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, X. et al. Widespread resistance of the aphid Myzus persicae to pirimicarb across China, and insights on ace2 mutation frequency in this species. Entomol Gen, 285–299 (2017).

- 10.Cui L, Qi H, Yang D, Yuan H, Rui C. Cycloxaprid: a novel cis-nitromethylene neonicotinoid insecticide to control imidacloprid-resistant cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii) Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2016;132:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merzendorfer H, Zimoch L. Chitin metabolism in insects: structure, function and regulation of chitin synthases and chitinases. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:4393–4412. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, et al. Chitin synthase 1 gene and its two alternative splicing variants from two sap-sucking insects, Nilaparvata lugens and Laodelphax striatellus (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;42:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Leeuwen T, et al. Population bulk segregant mapping uncovers resistance mutations and the mode of action of a chitin synthesis inhibitor in arthropods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:4407–4412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansur JF, et al. Effects of chitin synthase double-stranded RNA on molting and oogenesis in the Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;51:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Souza-Ferreira PS, et al. Chitin deposition on the embryonic cuticle of Rhodnius prolixus: The reduction of CHS transcripts by CHS–dsRNA injection in females affects chitin deposition and eclosion of the first instar nymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;51:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimoch L, Merzendorfer H. Immunolocalization of chitin synthase in the tobacco hornworm. Cell and tissue research. 2002;308:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shang F, et al. Identification, characterization and functional analysis of a chitin synthase gene in the brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida (Hemiptera, Aphididae) Insect Mol Biol. 2016;25:422–430. doi: 10.1111/imb.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal R, Mian MR, Mittapalli O, Michel AP. Characterization of a chitin synthase encoding gene and effect of diflubenzuron in soybean aphid, Aphis glycines. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1323. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang WJ, Xu KK, Cong L, Wang JJ. Identification, mRNA expression, and functional analysis of chitin synthase 1 gene and its two alternative splicing variants in oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:331. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashfaq M, Sonoda S, Tsumuki H. Developmental and tissue-specific expression of CHS1 from Plutella xylostella and its response to chlorfluazuron. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2007;89:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Zhang J, Park Y, Zhu KY. Identification and characterization of two chitin synthase genes in African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;42:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X, Liu X, Zhang Q, Wu J. Morph-specific differences in biochemical composition related to flight capability in the wing-polyphenic Sitobion avenae. Entomol Exp Appl. 2011;138:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kullik SA, Sears MK, Schaafsma AW. Sublethal effects of Cry 1F Bt corn and clothianidin on black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larval development. J Econ Entomol. 2011;104:484–493. doi: 10.1603/ec10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhadialla TS, Carlson GR, Le DP. New insecticides with ecdysteroidal and juvenile hormone activity. Annu Rev Entomol. 1998;43:545–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohrabi F, Shishehbor P, Saber M, Mosaddegh M. Lethal and sublethal effects of buprofezin and imidacloprid on Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Crop Prot. 2011;30:1190–1195. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasr HM, Badawy ME, Rabea EI. Toxicity and biochemical study of two insect growth regulators, buprofezin and pyriproxyfen, on cotton leafworm Spodoptera littoralis. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2010;98:198–205. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P, Zhao Y-H, Wang QH, Mu W, Liu F. Lethal and sublethal effects of the chitin synthesis inhibitor chlorfluazuron on Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae) Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2017;136:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohrabi F, Shishehbor P, Saber M, Mosaddegh MS. Lethal and sublethal effects of buprofezin and imidacloprid on the whitefly parasitoid Encarsia inaron (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) Crop Prot. 2012;32:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali E, et al. Sublethal effects of buprofezin on development and reproduction in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) Scientific reports. 2017;7:16913. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Zhou C, Long GY, Yang H, Jin DC. Sublethal effects of buprofezin on development, reproduction, and chitin synthase 1 gene (SfCHS1) expression in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2018;21:585–591. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali, E., Mao, K., Liao, X., Jin, R. & Li, J. Cross-resistance and biochemical characterization of buprofezin resistance in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Horvath). Pestic Biochem Physiol (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ishaaya I, Mendel Z, Blumberg D. Effect of buprofezin on California red scale, Aonidiella aurantii (Maskell), in a citrus orchard. Isr J Entomol. 1992;25:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, et al. Buprofezin susceptibility survey, resistance selection and preliminary determination of the resistance mechanism in Nilaparvata lugens (Homoptera: Delphacidae) Pest Management Science: formerly Pesticide Science. 2008;64:1050–1056. doi: 10.1002/ps.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desneux N, et al. Diaeretiella rapae limits Myzus persicae populations after applications of deltamethrin in oilseed rape. J Econ Entomol. 2005;98:9–17. doi: 10.1093/jee/98.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desneux N, Decourtye A, Delpuech JM. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 2007;52:81–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan H, et al. Lethal and sublethal effects of cycloxaprid, a novel cis-nitromethylene neonicotinoid insecticide, on the mirid bug Apolygus lucorum. J Pest Sci. 2014;87:731–738. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo C, Li D, Qu Y, Zhao H, Hu Z. Indirect effects of chemical hybridization agent SQ-1 on clones of the wheat aphid Sitobion avenae. Entomol Gen. 2018;38:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passos LC, et al. Lethal, sublethal and transgenerational effects of insecticides on Macrolophus basicornis, predator of Tuta absoluta. Entomol Gen. 2018;38:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jam NA, Saber M. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid and pymetrozine on the functional response of the aphid parasitoid, Lysiphlebus fabarum. Entomol Gen. 2018;38:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohammed A, et al. Impact of imidacloprid and natural enemies on cereal aphids: Integration or ecosystem service disruption. Entomol Gen. 2018;37:47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo L, et al. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of chlorantraniliprole on biological traits of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. Crop Prot. 2013;48:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan Y, Biondi A, Desneux N, Gao XW. Assessment of physiological sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the mirid bug Apolygus lucorum (Meyer-Dür) Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1989–1997. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu Y, et al. Sublethal and hormesis effects of beta-cypermethrin on the biology, life table parameters and reproductive potential of soybean aphid Aphis glycines. Ecotoxicology. 2017;26:1002–1009. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guedes R, Smagghe G, Stark J, Desneux N. Pesticide-induced stress in arthropod pests for optimized integrated pest management programs. Annu Rev Entomol. 2016;61:43–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, et al. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of short-term and chronic exposures to the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii. J Pest Sci. 2017;90:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calabrese EJ. Paradigm lost, paradigm found: the re-emergence of hormesis as a fundamental dose response model in the toxicological sciences. Environ Pollut. 2005;138:378–411. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayyanath MM, Cutler GC, Scott-Dupree CD, Sibley PK. Transgenerational shifts in reproduction hormesis in green peach aphid exposed to low concentrations of imidacloprid. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qu Y, et al. Sublethal and hormesis effects of imidacloprid on the soybean aphid Aphis glycines. Ecotoxicology. 2015;24:479–487. doi: 10.1007/s10646-014-1396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koo HN, Lee SW, Yun SH, Kim HK, Kim GH. Feeding response of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii, to sublethal rates of flonicamid and imidacloprid. Entomol Exp Appl. 2015;154:110–119. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chi H, Liu H. Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bull. Inst. Zool. Acad. Sin. 1985;24:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chi H. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals. Environ Entomol. 1988;17:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chi H. Timing of control based on the stage structure of pest populations: a simulation approach. J Econ Entomol. 1990;83:1143–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akca I, Ayvaz T, Yazici E, Smith CL, Chi H. Demography and population projection of Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae): with additional comments on life table research criteria. J Econ Entomol. 2015;108:1466–1478. doi: 10.1093/jee/tov187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chi, H. TWOSEX-MS Chart: A computer program for the age-stage, two-sex life table analysis, http://140.120.197.173/Ecology/Download/Twosex-MSChart-exe-B200000.rar. (2018).

- 55.Yuan HB, et al. Lethal, sublethal and transgenerational effects of the novel chiral neonicotinoid pesticide cycloxaprid on demographic and behavioral traits of Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Insect Sci. 2017;24:743–752. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerami S, Jahromi K, Ashouri A, Rasoulian G, Heidari A. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid and pymetrozine on the life table parameters of Aphis gossypii Glover (Homoptera: Aphididae) Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2005;70:779–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lashkari MR, Sahragard A, Ghadamyari M. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid and pymetrozine on population growth parameters of cabbage aphid, Brevicoryne brassicae on rapeseed, Brassica napus L. Insect Sci. 2007;14:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boina DR, Onagbola EO, Salyani M, Stelinski LL. Antifeedant and sublethal effects of imidacloprid on Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Pest Management Science: formerly Pesticide Science. 2009;65:870–877. doi: 10.1002/ps.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atsushi K, Rikio Y, Takamichi K. Effect of buprofezin on oviposition of brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, at sub-lethal dose. J Pestic Sci. 1996;21:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardson M, Lagos D. Effects of a juvenile hormone analogue, pyriproxyfen, on the apterous form of soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) J Appl Entomol. 2007;131:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casewell NR, Wüster W, Vonk FJ, Harrison RA, Fry BG. Complex cocktails: the evolutionary novelty of venoms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sial AA, Brunner JF. Lethal and sublethal effects of an insect growth regulator, pyriproxyfen, on obliquebanded leafroller (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) J Econ Entomol. 2010;103:340–347. doi: 10.1603/ec09295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esmaeily S, Samih MA, Zarabi M, Jafarbeigi F. Sublethal effects of some synthetic and botanical insecticides on Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) J Plant Prot Res. 2014;54:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu L, Zhao CQ, Zhang YN, Liu Y, Gu ZY. Lethal and sublethal effects of sulfoxaflor on the small brown planthopper Laodelphax striatellus. J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2016;19:683–689. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yousaf HK, et al. Impact of the secondary plant metabolite Cucurbitacin B on the demographical traits of the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. Scientific reports. 2018;8:16473. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34821-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X, et al. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of sulfoxaflor on the biological traits of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Ecotoxicology. 2016;25:1841–1848. doi: 10.1007/s10646-016-1732-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amini Jam N, Kocheili F, Mossadegh MS, Rasekh A. & Saber, M. Lethal and sublethal effects of imidacloprid and pirimicarb on the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae) under laboratory conditions. Journal of Crop Protection. 2014;3:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J, Zhu KY. Characterization of a chitin synthase cDNA and its increased mRNA level associated with decreased chitin synthesis in Anopheles quadrimaculatus exposed to diflubenzuron. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xia WK, et al. Exposure to diflubenzuron results in an up-regulation of a chitin synthase 1 gene in citrus red mite, Panonychus citri (Acari: Tetranychidae) International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15:3711–3728. doi: 10.3390/ijms15033711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gangishetti U, et al. Effects of benzoylphenylurea on chitin synthesis and orientation in the cuticle of the Drosophila larva. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merzendorfer H, et al. Genomic and proteomic studies on the effects of the insect growth regulator diflubenzuron in the model beetle species Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;42:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gong Y, Shi X, Desneux N, Gao X. Effects of spirotetramat treatments on fecundity and carboxylesterase expression of Aphis gossypii Glover. Ecotoxicology. 2016;25:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s10646-016-1624-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei X, et al. Cross-resistance pattern and basis of resistance in a thiamethoxam-resistant strain of Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2017;138:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moores GD, Gao X, Denholm I, Devonshire AL. Characterisation of insensitive acetylcholinesterase in insecticide-resistant cotton aphids, Aphis gossypii Glover (homoptera: Aphididae) Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1996;56:102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Biondi A, Desneux N, Siscaro G, Zappalà L. Using organic-certified rather than synthetic pesticides may not be safer for biological control agents: selectivity and side effects of 14 pesticides on the predator Orius laevigatus. Chemosphere. 2012;87:803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ma, K. S. et al. Identification and validation of reference genes for the normalization of gene expression data in qRT-PCR analysis in Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Journal of Insect Science16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Finney, D. J. Probit Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1971).

- 79.Huang YB, Chi Hsin. The age-stage, two-sex life table with an offspring sex ratio dependent on female age. Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2011;60(4):337–345. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tuan SJ, Lee CC, Chi H. Population and damage projection of Spodoptera litura (F.) on peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) under different conditions using the age-stage, two-sex life table. Pest Manag Sci. 2014;70:805–813. doi: 10.1002/ps.3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Efron, B. & Tibshirani, R. J. An introduction to the bootstrap. (CRC press, 1994).

- 82.Akköprü EP, Atlıhan R, Okut H, Chi H. Demographic assessment of plant cultivar resistance to insect pests: a case study of the dusky-veined walnut aphid (Hemiptera: Callaphididae) on five walnut cultivars. J Econ Entomol. 2015;108:378–387. doi: 10.1093/jee/tov011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Files). Supplementary Table S1: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to control solution. Supplementary Table S2: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to LC15 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S3: Lifetable of adult A. gossypii (F0 generation) following 72-h exposure to LC30 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S4: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by untreated adult A. gossypii. Supplementary Table S5: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by parental A. gossypii treated with LC15 of buprofezin. Supplementary Table S6: Lifetable of progeny generation (F1) produced by parental A. gossypii treated with LC30 of buprofezin.