Abstract

Background:

Midyear disenrollment from Marketplace coverage may have detrimental effects on continuity of care and risk pool stability of individual health insurance markets.

Objective:

The main objective of this study was to assess associations between insurance plan characteristics, individual and area-level demographics, and disenrollment from Marketplace coverage.

Data:

All payer claims data from individual market enrollees, 2014–2016.

Study Design:

We estimated Cox proportional hazards models to assess the relationship between plan actuarial value and Marketplace enrollment. The primary outcome was disenrollment from Marketplace coverage before the end of the year. We also calculated the proportion of enrollees who transitioned to other coverage after leaving the Marketplace, and identified demographic and area-level factors associated with early disenrollment. Finally, we compared monthly utilization rates between those who disenrolled early and those who maintained coverage.

Results:

Nearly 1 in 4 Marketplace beneficiaries disenrolled midyear. The hazard rate of disenrollment was 30% lower for individuals in plans receiving cost-sharing reductions and 21% lower for those enrolled in gold plans, compared with silver plans without cost-sharing subsidies. Young adults had a 70% increased hazard of disenrollment compared with older adults. Those who disenrolled midyear had greater hospital and emergency department utilization before disenrollment compared with those who maintained continuous coverage.

Conclusions:

Plan generosity is significantly associated with lower disenrollment rates from Marketplace coverage. Reducing churning in Affordable Care Act Marketplaces may improve continuity of care and insurers’ ability to accurately forecast the health care costs of their enrollees.

Keywords: health insurance, individual market, actuarial value, out-of-pocket costs, Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) led to major increases in coverage, but less is known about continuity of coverage over time.1,2 Midyear disenrollment from Marketplace coverage can lead to gaps in insurance that may compromise access to care and health outcomes.3 Some disenrollees may become uninsured, and switches between different insurance plans can erode continuity of care due to misalignment between plans and/or providers.4,5 Midyear Marketplace disenrollment may also destabilize health insurance markets. To our knowledge, there are no published studies on the prevalence and predictors of early disenrollment from the ACA’s individual Marketplace plans.

The decision whether to disenroll from health insurance is multifactorial, and prior research has used different theoretical approaches to model consumers’ insurance decisions.6,7 In ACA Marketplaces, relevant factors include employment, health status, income, age, health care utilization, risk aversion, and perceived value of health insurance. Whether enrollees are eligible for public health insurance programs or have an offer of employer-based coverage determines available insurance options which may change over time. Plans’ benefit generosity and provider networks may also guide insurance decisions. Prior work has demonstrated that consumers are sensitive to changes in monthly premiums and out-of-pocket costs such as coinsurance and deductibles.8,9 Hendryx et al8 found that among those who disenrolled voluntarily from a Basic Health Plan in Washington following cost-sharing increases, 34% cited the increases as a reason for their decision. In the individual Marketplace, plans vary by actuarial value (AV), income-based eligibility for financial assistance, benefit structure and provider networks. Although financial assistance improves affordability of Marketplace coverage, out-of-pocket costs can remain burdensome, particularly for those with incomes too high to qualify for cost-sharing subsidies.10,11

Using all payer claims data from Colorado’s state-based Marketplace, we examined the frequency of early Marketplace dropout and compared disenrollment rates between consumers exposed to varying levels of insurance costs. We also assessed the proportion of enrollees who transitioned to other sources of coverage after exiting the Marketplace, identified demographic and area-level risk factors for early disenrollment, and compared utilization rates by whether enrollees maintained continuous coverage.

METHODS

Data and Study Population

We obtained Colorado’s all payer claims database (APCD), which contain health insurance claims from the 21 largest commercial payers, Medicaid, and 11 Marketplace plans that capture 85%–90% of Marketplace enrollees. Selffunded plans regulated under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) are not required to submit their claims to the APCD, excluding ~20% of the total commercially insured market. The data set does not include claims from individuals who are uninsured, who selfpay, who have moved out of state, or disenrollees who become uninsured or switch to a plan not included in the APCD.

We tracked insurance transitions longitudinally from 2014 to 2016 using a unique person identifier that enabled the linkage of claims and enrollment data across insurance types. Our final study population included 186,485 Marketplace enrollees (307,937 person-years) under the age of 63 who paid premiums for at least one month in a nongrandfathered Marketplace health insurance plan.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was early disenrollment from Marketplace coverage, defined as disenrollment before the end of the calendar year. Each year of enrollment was treated independently and duration of enrollment was measured by month. Instances in which enrollees exited and reentered the plan during the calendar year were not counted as disenrollment. Health insurance transitions were defined as enrollment in Medicaid or other commercial coverage within 6 months of disenrollment from Marketplace coverage. Measures of health care utilization included monthly rates of emergency department use, inpatient stays, office-based visits and a rate that captured all claim-based interactions with the healthcare system, excluding pharmaceutical claims.12

Cost-Sharing Measures

Bronze, silver, gold, and platinum tier Marketplace plans have average annual AVs of 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90%, respectively.13 Enrollees pay their portion of health care costs in the form of cost-sharing, copayments, and deductibles. As Colorado is a Medicaid expansion state, plan members with incomes between 138% and 400% Federal Poverty Level (FPL) are eligible for premium subsidies; silver plan members with incomes between 100% and 250% FPL are eligible for meanstested cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) if they purchase silver tier plans. For those eligible for CSRs, the AV of a standard silver plan is raised to 72%, 87%, and 94% for those with incomes 200% to 250% FPL, 150% to 200% FPL, and 100% to 150% FPL, respectively. Those who are eligible for CSRs are also eligible for premium subsidies, but only a portion of those eligible for premium subsidies also qualify for CSRs.

Enrollees were categorized into 1 of 6 types of plans: bronze (60% AV), silver with no CSR (70% AV), silver with CSRs for incomes 200% to 250% FPL (72%), 150% to 200% FPL (87% AV), and 100% to 150% FPL (94% FPL), and gold (90% AV). Colorado had no platinum plans. All ZIP code level variables were drawn from the 2014 Census American Community Survey (ACS) and entered into the model as standardized variables such that hazard ratios (HRs) correspond to a one-SD increase in the predictor.

Analysis

We estimated Cox proportional hazards models to assess predictors of early Marketplace disenrollment treating each person-year of enrollment as unordered failure events of the same type (Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B650). Multivariate results are expressed as HRs. Enrollees were right-censored if they did not disenroll before January of the following year. We estimated a model for the 6 categories of AV, adjusting for age, sex, ZIP code level race/ethnicity and educational status.

RESULTS

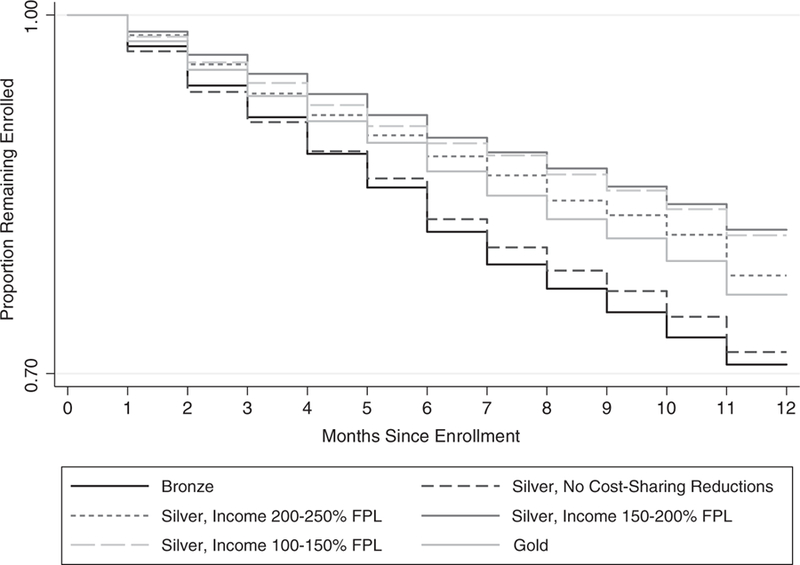

Table 1 displays demographic characteristics (N = 307,937 person-years) by metallic tier and CSR status. Table 2 displays enrollment statistics by metallic tier and CSR status. Overall, 24.1 percent of Marketplace beneficiaries disenrolled before January of the following year. Disenrollment rates were 15.9%, 30.9%, and 26.4% in 2013, 2014, and 2015, respectively. Disenrollment was highest among bronze enrollees (26.3%), followed by silver enrollees receiving no CSRs (25.2%), and lowest among silver enrollees receiving CSRs (18.6%) (between group P < 0.001). Figure 1 displays Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Marketplace enrollees by plan AV. Among silver enrollees, those who received CSRs were less likely to disenroll over the study period than those who did not receive CSRs. Within cost-sharing tiers of the silver plan, there were significant differences between the least generous CSR (for those with incomes 200%–250% FPL) compared with the relatively more generous subsidies for those 150%–200% FPL (P = 0.005) and 100%–150% FPL (P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Colorado Marketplace Enrollees by Metallic Tier of Plan

| Variables | Bronze Enrollees | Silver Enrollees Without Cost-Sharing Reductions | Silver Enrollees Receiving Cost-Sharing Reductions | Gold Enrollees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Enrollment | 102,296 | 123,375 | 40,317 | 41,949 |

| Enrollment by year [N (%)] | ||||

| 2014 | 32,707 (32.0) | 41,609 (33.7) | 15,256 (37.8) | 14,065 (33.5) |

| 2015 | 25,747 (25.2) | 34,978 (28.4) | 13,352 (33.1) | 13,910 (33.2) |

| 2016 | 43,842 (42.9) | 46,788 (37.9) | 11,709 (29.0) | 13,974 (33.3) |

| Age [mean (SE)] | 38.8 (0.052) | 38.5 (0.048) | 38.1 (0.084) | 34.3 (0.083) |

| Female (%) | 50.2 | 53.3 | 52.9 | 52.6 |

| Area-level variables | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 86.0 | 85.4 | 89.5 | 86.9 |

| Black | 3.3 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.0 |

| Asian American | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.8 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.3 | 18.1 | 15.3 | 16.2 |

| Median household income | $66,812 | $66,218 | $61,369 | $67,135 |

| Income below Federal Poverty | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 11.6 |

| Level (%) | ||||

| Uninsurance (%) | 12.9 | 13.2 | 15.2 | 12.9 |

| Unemployed (%) | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.3 |

| Completed high school (%) | 91.9 | 91.5 | 91.8 | 92.2 |

All area-level variables, including race/ethnicity, income, poverty, uninsurance, unemployment, and education represent the distribution of those variables in the enrollee’s ZIP code of residence using data from the 2014 American Community Survey.

TABLE 2.

Early Disenrollment, Duration of Enrollment, and Insurance Transitions, by Metallic Tier and the Receipt of Cost-Sharing Reductions

| Variables | Full Sample | Bronze Enrollees | Silver Enrollees Without Cost-Sharing Reductions | Silver Enrollees Receiving Cost-Sharing Reductions | Gold Enrollees | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early disenrollment (%) | 24.1 | 26.3 | 25.2 | 18.6 | 21.0 | < 0.001 |

| 2014 | 15.9 | 18.1 | 16.8 | 12.0 | 12.4 | < 0.001 |

| 2015 | 30.9 | 35.7 | 34.0 | 19.5 | 24.8 | < 0.001 |

| 2016 | 26.4 | 25.2 | 26.1 | 26.2 | 25.8 | < 0.001 |

| Mean enrollment duration (d) | 275.7 | 269.4 | 272.0 | 293.0 | 285.7 | < 0.001 |

| Insurance transition type among those who disenrolled early from Marketplace coverage | ||||||

| Disenrollees (N) | 74,296 | 26,906 | 31,115 | 7484 | 8791 | |

| Marketplace to Medicaid (%) | 10.4 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 14.4 | 8.4 | < 0.001 |

| Marketplace to commercial (%) | 17.0 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 20.1 | 23.1 | < 0.001 |

| Lost to follow-up (%) | 72.6 | 74.8 | 73.6 | 65.4 | 68.5 | < 0.001 |

P-values were computed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance F-tests for the comparison of multiple means.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of enrollment in Marketplace coverage, by plan actuarial value in order to differentiate disenrollment across plans, the y-axis was limited to the range of observed probabilities, 0.70–1.00 (2014–2016).

Table 3 displays adjusted and unadjusted HRs of early Marketplace disenrollment. In adjusted analyses, relative to those receiving no CSRs, silver enrollees receiving CSRs had a 21%–32% reduced hazard of disenrollment depending on which tier of income-based cost-sharing subsidies they were eligible for based on their incomes. Those enrolled in gold plans had a 21% lower hazard of disenrollment and those enrolled in bronze plans had a 7% increased hazard of disenrollment compared with silver enrollees receiving no CSRs.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted and Unadjusted Cox Proportional Hazard Models of Early Marketplace Disenrollment, 2014–2016

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| Silver, no cost-sharing reduction | Reference | Reference |

| Bronze | 1.05 (0.016)** | 1.07 (0.020)*** |

| Silver, cost-sharing reduction for incomes 200%–250% FPL | 0.73 (0.064)*** | 0.79 (0.072)* |

| Silver, cost-sharing reduction for incomes 150%–200% FPL | 0.59 (0.057)*** | 0.68 (0.059)*** |

| Silver, cost-sharing reduction for incomes 100%–150% FPL | 0.61 (0.052)*** | 0.70 (0.067)*** |

| Gold | 0.79 (0.073)* | 0.79 (0.057)** |

| Female | 1.00 (0.010) | |

| Age (y) | ||

| 0−17 | 1.30 (0.030)*** | |

| 18−29 | 1.70 (0.078)*** | |

| 30−44 | 1.48 (0.015)*** | |

| 45−63 | Ref | |

| ZIP code level factors (%) | ||

| Graduated high school | 1.07 (0.020)*** | |

| White | 1.01 (0.046) | |

| Black | 1.07 (0.014)*** | |

| Asian | 1.11 (0.039)** | |

| Hispanic | 1.16 (0.024)*** | |

| Observations | 307,937 | 307,937 |

All ZIP code level factors are standardized so that each additional unit of the predictor corresponds to a one-SD increase. Observations were clustered within person, within geographic area, and within health insurance plan. SEs were clustered at the highest level of aggregation (the plan).14,15

FPL indicates Federal Poverty Level.

P < 0.10.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Compared with 45–63 year olds, the hazard of disenrollment was 30% higher among children under 18 years of age, 70% higher among 18–29 year olds, and 48% higher among 30–44 year olds. The majority of 18–29 year olds enrolled in silver plans but did not receive CSRs. Living in a ZIP code with a greater proportion of Black, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino residents was associated with an increased hazard of early Marketplace disenrollment of 7%, 11%, and 16%, respectively (per SD of change in the predictor).

Those who disenrolled early had higher monthly rates of emergency department use, hospitalization, and overall utilization but lower monthly rates of office-based services compared to those who stayed continuously enrolled (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Monthly Utilization Rates Among Those Who Disenrolled Early Compared With Those Who Maintained Continuous Enrollment

| Disenrolled Before 12 mo of Coverage | Maintained Continuous Enrollment | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean monthly ED visit rate | 0.024 | 0.013 | < 0.001 |

| Mean monthly hospitalization rate | 0.008 | 0.005 | < 0.001 |

| Mean monthly office visit rate | 0.120 | 0.148 | < 0.001 |

| Mean monthly nonpharmaceutical utilization rate of any kind | 0.732 | 0.541 | < 0.001 |

P-values were computed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance F-tests for the comparison of multiple means. ED indicates emergency department.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of Colorado all payer claims data from 2014 to 2016, we found that nearly 25% of Marketplace beneficiaries disenrolled from coverage after <12 months. To our knowledge, this study represents the first estimate of within-year Marketplace attrition in the peer-reviewed literature since the passage of the ACA. Our finding that 24.3% of those in the Colorado Marketplace disenrolled before the end of the year indicates that Colorado experienced a somewhat lower dropout rate than national estimates (28%) and state predictions (30%).16,17 Compared with receiving no CSRs, the hazard of disenrollment decreased as the AV of the plans increased. Among silver enrollees, the AVs of those enrolled in silver plans receiving the least generous CSRs and those receiving no CSRs differ by only 2 percentage points (70% vs. 72% AV). However, the survival functions of these 2 groups diverge. This divergence may reflect the fact that all enrollees who received CSRs were also eligible for varying levels of premium subsidies, which substantially lower the cost of insurance. However, the reference group (silver enrollees ineligible for CSRs) is a combination of those who pay subsidized premiums and those who pay unsubsidized premiums. Comparisons within the three income tiers of cost-sharing suggest that among those who receive premium subsidies, those who also received more generous financial assistance in the form of CSRs disenrolled at lower rates.

We also found that young adults disenrolled at higher rates compared with their older counterparts, a finding consistent with research on pre-ACA insurance markets.8 Those who disenrolled early had higher utilization rates for all measures except office-based visits. This may indicate that those who disenroll early utilize care in higher-cost acute settings and have lower engagement with routine, preventive services. Enrollees may drop their insurance after exposure to the costs associated with acute health care utilization, and/or may use more care early on in their enrollment due to pent-up or planned demand.

Although our results suggest cost is likely a factor in the decision to leave a Marketplace plan, other possible reasons include transitions to other types of insurance due to changes in employment or income. In our sample, 10.4% of those who disenrolled from Marketplace coverage midyear transitioned to Medicaid. A more common transition was from Marketplace coverage to employer-sponsored commercial coverage. Our estimate of 17% is a lower bound of those who disenrolled from Marketplace coverage midyear and transitioned to a non-Marketplace commercial insurance plan, since we do not capture many self-insured commercial plans.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, our findings may not generalize to the 10% to 15% of Colorado’s Marketplace enrollees that were not included in the APCD. Second, the APCD likely underestimates transition rates to other types of private coverage since the dataset does not include some Marketplace plans or ERISA-compliant selffunded commercial plans. Therefore, individuals who are lost to followup may have obtained commercial coverage from an insurer that does not report to the APCD, moved out of state, or died. Future studies using more complete APCD data should examine the sources of coverage (and rate of uninsurance) for this population after plan exit.

Third, this study considers only several of the potential factors predictive of health insurance decisions. Because many Coloradans gained coverage for the first time in 2014 when the state Marketplace opened, it was not possible to obtain prior data on health status or utilization. In addition, data on race/ethnicity and educational achievement were only available at the level of the ZIP code. We also could not identify which enrollees received premium subsidies if they did not also receive CSRs, nor quantify the generosity of those subsidies. More broadly, we cannot infer a causal relationship between any of our predictors and disenrollment. Lastly, our results focused on one state, which may not be generalizable to other Marketplaces or nonexpansion states.

Recent policy changes with regard to CSRs have implications for our findings. The Trump administration ceased CSR payments to insurance companies in October 2017. In anticipation of this decision, over 40 states allowed Marketplace insurers to raise silver plans rates to account for the losses. This resulted in increased premiums for unsubsidized enrollees, which may lead to greater disenrollment among higher-income beneficiaries. The elimination of the individual mandate penalty in 2019 may also contribute to greater disenrollment.

In conclusion, nearly one-quarter of Marketplace enrollees in Colorado disenrolled from their selected plan before the end of the year. Further, persons who received greater financial assistance disenrolled at lower rates. Taking steps to reduce Marketplace churning may promote continuity of coverage and reduce dropout rates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge technical support from the Colorado Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC).

Funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R36 Dissertation Award, Award Notice R36 HS025560-01 (S.H.G.).

Footnotes

Presented at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting (Seattle, WA) and the American Society of Health Economists Annual Meeting (Atlanta, GA) in June 2018.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2017;376:947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, et al. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA 2015;314:366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdus S Part-year coverage and access to care for nonelderly adults. Medical Care 2014;52:709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavarreda SA, Gatchell M, Ponce N, et al. Switching health insurance and its effects on access to physician services. Medical Care 2008;46: 1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orfield C, Hula L, Barna M, et al. The Affordable Care Act and access to care for people changing coverage sources. Am J Public Health 2015;105(suppl 5):S651–S657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long SH, Settle RF, Wrightson CW. Employee premiums, availability of alternative plans, and HMO disenrollment. Medical Care 1988;26:927–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eibner C, Girosi F, Miller A, et al. Employer self-insurance decisions and the implications of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as modified by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (ACA) 2011. Available at: www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR971.html. Accessed April 24, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hendryx M, Onizuka R, Wilson V, et al. Effects of a cost-sharing policy on disenrollment from a state health insurance program. Soc Work Public Health 2012;27:671–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchmueller TC, Feldstein PJ. The effect of price on switching among health plans. J Health Econ 1997;16:231–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumberg L, Holohan J, Buettgens M. How much do Marketplace and other nongroup enrollees spend on health care relative to their incomes? 2015. Available at: www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/76446/2000559-How-Much-Do-Marketplace-and-Other-Nongroup-Enrollees-Spend-on-Health-Care-Relative-to-Their-Incomes.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 11.Gabel JR, Whitmore H, Green M, et al. Consumer cost-sharing in Marketplace vs. employer health insurance plans, 2015 2015. Available at: www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/dec/cost-sharing-marketplace-employer-plans. Accessed December 5, 2017. [PubMed]

- 12.Choat DE. Coding for office procedures and activities. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2005;18:279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polyakova M, Hua LM, Bundorf MK. Marketplace plans provide risk protection, but actuarial values overstate realized coverage For most enrollees. Health Aff 2017;36:2078–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pepper JV. Robust inferences from random clustered samples: an application using data from the panel study of income dynamics. Econ Lett 2002;75:341–345. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron AC, Gelbach JB, Miller DL. Robust inference with multiway clustering. J Bus Econ Stat 2011;29:238–249. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Health insurance Marketplaces 2017 Open Enrollment period final enrolment report: November 1, 2016-January 31, 2017 2017. Available at: www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2017-Fact-Sheet-items/2017-03-15.html. Accessed January 5, 2018.

- 17.Semro B Colorado’s Health Exchange on target to meet budget goals. Huffington Post 2014. Available at: www.huffingtonpost.com/bob-semro/colorados-health-exchange_b_5947876.html. Accessed January 5, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.