Abstract

Introduction

Septic acute kidney injury (AKI) is the most common complication of septic shock and increases mortality. A large body of experimental data suggests alterations in renal perfusion occur, but this is yet to be fully assessed in humans. The aim of the current study is to observe the macro and microcirculations in both the systemic and renal circulations in a cohort of patients with early septic shock.

Methods and analysis

Single-centre, prospective, longitudinal, observational study of 50 patients with septic shock. Renal microcirculatory assessment will be performed with contrast-enhanced ultrasound, the sublingual microcirculation assessed with incident dark field microscopy and transthoracic echocardiography used to assess global flow. Patients will be enrolled as soon as possible after admission to the intensive care unit and then at +24,+48 and +96 hours. Blood samples of circulatory and renal biomarkers will be collected. Sample groups will be defined by the presence or absence of AKI and then subclassified by the severity (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria), variables will be compared within and between groups over time.

Ethics and dissemination

Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval has been granted for this study by Yorkshire and the Humber, Leeds West Research Ethics Committee (18/YH/0371) and due to the nature of the patients enrolled with septic shock, capacity for informed consent is likely to be lacking. Therefore, a personal consultee (friend or relative) will be consulted or a nominated consultee (clinician) in their absence. After capacity is regained, consent will then be sought from the patient in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act, UK (2005). This consent process has been approved following REC review. Results will be published in a relevant peer-reviewed journal and presented at academic meetings.

Keywords: microcirculation, acute renal failure, septic shock, contrast enhanced ultrasound, dark field microscopy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of the study is the use of novel imaging methods to assess the state of renal perfusion in early septic shock.

The study will add to the understanding of septic acute kidney injury, a common and life-threatening condition.

A limitation is the proof-of-concept observational nature of this study, using techniques not fully established in intensive care medicine. However, our team includes individuals with expertise of using all of the listed techniques.

A potential limitation is the lack of healthy controls. However, a potential collaboration with a group using healthy volunteers is under development.

A further limitation is an inability to measure total renal blood flow; we will attempt to develop a method of quantifying renal artery flow using contrast as an adjunct and to use previously described methods of assessing total renal perfusion with contrast. Although it may still not be feasible to accurately quantify in this patient group, it is not essential to the assessment of regional renal perfusion.

Background

Sepsis is the leading cause of emergency admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) in the UK.1 Data from recent large observational studies demonstrate that 50% of these patients go on to develop acute kidney injury (AKI), in isolation, or as part of a multiorgan dysfunction syndrome.2 3 AKI significantly increases inpatient mortality4 5 and longer term development of chronic kidney disease (CKD).6

Historical dogma has suggested that poor perfusion of the kidneys is a key factor in the pathogenesis of septic AKI7; however, recent preclinical studies have cast doubt on such assertions.8 9 Furthermore, the relationship between the systemic and renal circulations has yet to be clearly delineated, and it is possible that the two react in an incongruous fashion. An additional factor to consider is the relationship between the macrocirculation (heart and larger blood vessels) and the microcirculation (smaller vessels typically less than 20 microns diameter, where cellular substrate delivery occurs). Previous work examining the sublingual microcirculation has shown that there is often a breakdown of haemodynamic coherence between the macro and micro circulations in septic patients.10 11 However, there is virtually no data relating to the relationship between the macro and micro circulations at the level of individual organs, such as the kidney.

All of the factors considered here have important implications for patient care. Resuscitation, with fluid or vasoactive drugs, can, if targeted at inappropriate endpoints, lead to harm.12–16 Improved knowledge of the state of renal perfusion during septic shock should allow the creation of more targeted resuscitation strategies in the future.

The present study is designed as a key translational step from experimental data to real-time quantification of renal perfusion in patients with septic shock to determine its role in AKI development. We will use three techniques to observe the haemodynamic response to sepsis within the kidney and wider circulations. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) will be used to study microcirculatory flow within the kidney, an evolving technique that has proved feasible in critically ill patients17 18 and has been achieved in a smaller cohort of patients with septic shock.19 Contrast-assisted renal artery doppler, resistive index and CEUS will also quantify renal artery velocity and provide an estimation of renal blood flow and total perfusion.20 Sublingual incident dark field (IDF) videomicroscopy will provide data on a central microcirculatory bed that has been shown to correlate with outcome in a multitude of clinical conditions.11 21 Finally, a full transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) study will provide detail on systemic haemodynamic function.22

Primary objectives

The primary objective of the study is to observe the changes in haemodynamic perfusion variables at both macro and micro circulatory levels and in both the kidney and systemic circulations for patients with septic shock. With the primary outcome being renal perfusion changes in patients who do (stages 1,2 and 3) and do not develop AKI (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes staging criteria23).

Methods

Study design

Single-centre prospective longitudinal observational study. Serial assessments will be taken using the described devices: CEUS, IDF video microscopy and TTE. Resuscitation protocols including fluid type, volume and selection of vasoactive agents will remain at the discretion of the treating clinician for the study period; these variables will be recorded but not controlled for in this pragmatic observational study.

Patient screening

All patients presenting to the Critical Care Units of King’s College Hospital, London, UK, will be screened by research staff to assess eligibility. Patient details will be recorded in a screening log. This study includes all patients who present with septic shock provided they meet the inclusion criteria, the study is observational so all patients will be treated equally and the primary outcome of AKI will only be known by day 28. Randomisation and blinding of the study is therefore not appropriate.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was derived from a power calculation using the limited available CEUS studies in critically ill patients.17 19 AKI will be defined using the worst Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) stage in the first 28 days after admission. Patients will be dichotomised into those with AKI (KDIGO stages 1–3) and without AKI. Based on an estimated difference in perfusion index of 1000 au between groups (AKI present and AKI absent) and on an SD of 1000 au and assuming a power of 90% and alpha of 0.05, 22 patients in each group (n=44) are required to detect a difference in perfusion index, assuming approximately 50% of patients with septic shock develop AKI.19 24 In order to address potential for missing data or loss to follow-up, then we will aim to recruit 50 patients.

Enrolment commenced in November 2018 and will run until 50 patients are recruited.

Defining AKI

AKI will be staged using KDIGO criteria. Urine output will be used to define AKI severity as per KDIGO criteria. Any patient who receives renal replacement therapy (RRT) during their admission will be labelled as AKI stage 3 (long-term dialysis patients are excluded).

Common to AKI research, the baseline creatinine value is not always known and therefore the increase is not possible to quantify. We therefore will take the following approach, while not perfect is a pragmatic solution: We will identify the lowest creatinine of any that may have been taken in the prior 12 months as a baseline value. If no preadmission creatinine is available, then the lowest value the creatinine returns to after shock has resolved will be used (it is likely the value prior to admission was equal or lower to this post-ICU) value). Failing all of the above the admission creatinine will be used as the baseline value.

Inclusion criteria

Over 18 years old.

≤24 hours of ICU admission.

Evidence of suspected or confirmed infection.

Serial Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score increase of 2 or greater.

Requiring vasopressor support to maintain mean arterial blood pressure >65 mm Hg.

Arterial blood lactate >2.0 mmol/L after initial fluid resuscitation.

These criteria are those defined by the Third International Consensus Criteria for Sepsis and Septic Shock.25

Exclusion criteria

Known intolerance to Sonovue ultrasound contrast agent.

Contraindications listed by the contrast manufacturer:

Established acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Pregnancy.

Breastfeeding mothers.

Severe pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery systolic pressure >90 mm Hg) measured by transthoracic echocardiography.

Coadministration of dobutamine.

Patients in whom initial treatment is palliative.

Known CKD stage 4 and stage 5 (baseline glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <30 mL/min).

Patients with bilaterally small kidneys on ultrasound (<9 cm).

Patients with a renal transplant.

Time points and techniques for data collection

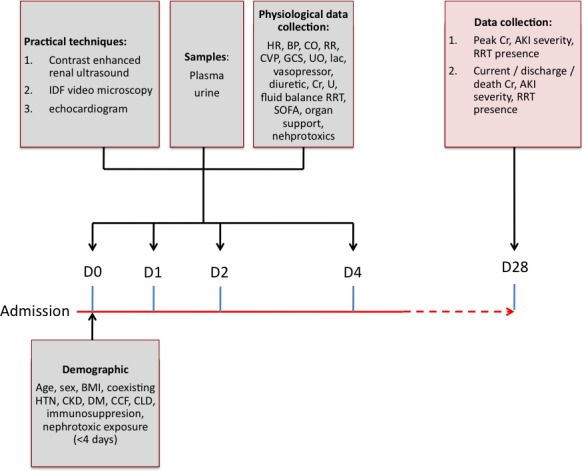

Figure 1 describes the data collected at the various time points. There are four time points: admission (D0), after 24 hours (D1), 48 hours (D2) and 96 hours (D4). The last time point was selected to capture patients who may be established on renal replacement with severe AKI and before recovery has occurred.

Figure 1.

Investigation timeline for a single patient enrolled in the MICROSHOCK – RENAL study. AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CCF, heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; CO, cardiac output; Cr, creatinine; CVP, central venous pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; GCS, glasgow coma scale; HR, heart rate; HTN, hypertension; IDF, incident dark field; lac, arterial blood lactate; RR, respiratory rate; SOFA, Serial Organ Failure Assessment; U, urea; UO, urine output (ml/hr).

Demographic and resuscitation data

The following data will be collected at baseline and stored on a secure encrypted deidentified database with a unique study number assigned:

Demographic (age, sex and body mass index) and comorbidities.

Suspected site of infection by organ system.

SOFA score.

Physiological data (heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure, cardiac output (measured by echocardiographic assessment in all patients and arterial pressure waveform analysis if clinically required), arterial oxygen tension (or pressure)/fractional inspired oxygen ratio, peak inspiratory pressure, positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), tidal volume, central venous pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale, arterial base excess (BE), lactate, CO2 gap (central venous partial pressure of carbon dioxide - arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PcvCO2 − PaCO2)), central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) and temperature).

Renal variables (urine output hourly and previous 24 hours, cumulative diuretic dose, presence of renal replacement therapy and dose, serum creatinine, presence of a nephrotoxic agent or other cause of AKI identified, fluid balance, total volume of administered fluid previous 24 hours and type of fluid).

Laboratory data (haemaglobin, platelets, bilirubin, creatinine, urea, white blood cell count, C reactive protein and microbiology).

Baseline creatinine if measured in the 12 months prior to admission.

IDF microscopy for the haemodynamic assessment of the systemic microcirculation

Videos of sublingual microcirculation will be acquired using an IDF video-microscope (Cytocam, Braedius Medical, Huizen, The Netherlands). Following suctioning of the oropharynx, a gauze swab is applied to gently remove saliva from the mucosal surface. The camera probe is applied to the sublingual area and images selected (taking care to exclude areas of buccal microcirculation with large numbers of looped vessels). After image optimisation a minimum of 3, and ideally 5, video images of the sublingual microcirculation will be taken at each experimental time point, each recorded clip consisting of 100 video frames at a rate of 20 frames per second. Images will be batch-analysed offline and blinded to the investigator, using Automated Vascular Analysis software (AVA) V.3.02 (Microvision Medical, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Data collection and analysis will be performed by one of two investigators specifically trained in its use and with prior experience of the technique.

Cardiac echocardiography for the haemodynamic assessment of the systemic macrocirculation

Cardiac echocardiography will be performed to quantify global haemodynamic status, and a comprehensive echocardiogram will be undertaken gathering the minimum dataset required by the British Society of Echocardiography.26 The echocardiogram along with vital signs and standard ICU monitoring (as described in Levels Of Critical Care for Adult Patients; Intensive Care Society 2009) will be used to quantify macrocirculatory changes, cardiac output and calculated pulmonary artery pressures.

Contrast-enhanced renal ultrasound images for the haemodynamic assessment of the renal microcirculation

Renal ultrasound, including the use of contrast will be performed using an Affiniti ultrasound system (Philips, UK).

Conventional grayscale US imaging will be performed. The investigator will vary the pulse repetition frequency, focal zone, gain and wall filter as necessary to obtain optimal sonograms in each case. Both kidneys will be visualised and provided both kidneys are sonographically normal, the most accessible will be chosen to perform the study. Baseline greyscale and colour Doppler sonographic images will be recorded.

A low mechanical index (MI) technique (range: 0.04–0.1) for CEUS will be used with MI set at or below 0.10. An infusion of 4.8 mL of SonoVue (Bracco SpA, Milan, Italy), contrast agent, will be administered by a dedicated infusion pump at a rate of 1 mL/min.

Images of the entire examination will be digitally recorded. The recording of the examination is initiated at the start of the contrast injection and all time measurements started from these moments, which are defined as ‘time-0’ in all recorded video clips. Measurements will be concluded after approximately 5 min with approximately five high-frequency pulses and reperfusion episodes.

Postprocessing will then be performed offline with dedicated software to permit objective quantitative analysis divided by regions of interest. Areas of cortex and medulla will be analysed and compared with assessment of mean transit time, perfusion index and relative blood volume (RBV). Wash in curves will also be assessed. Data collection will be undertaken by one of two investigators, with appropriate training by an expert from within the radiology department at our hospital.

Renal artery Doppler for the haemodynamic assessment of the renal macrocirculation

We will record the Resistive Index of an interlobular artery ((peak systolic velocity - end diastolic velocity)/peak systolic velocity) although more reflective of vascular elasticity than flow. We will also identify the renal artery using contrast and measure the velocity time integral waveform at the sampling time points, which while not giving an absolute measure of flow, will provide a relative measure.

Blood and urine samples

Biochemical analysis will be undertaken at each time point. This will include urine output and creatinine to quantify the stage of AKI using the KDIGO classification.27 ELISA will be undertaken on a number of proposed proteins, and therefore urine, plasma and serum will be taken and stored for analysis of biomarkers. Recently described urinary cell-cycle arrest regulatory proteins (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-7) will be quantified. These are currently the earliest biomarkers and provide both good sensitivity and specificity for septic AKI.28 In addition, more established biomarkers for AKI will also be measured including kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and soluble trigger receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1).29

In order to further understand the impact of microcirculatory changes on the endothelium, vascular biomarkers will also be assessed. The following three biomarkers will be measured: Angiopoietin 1 and 2 are a family of vascular growth factors indicative of vascular permeability and syndecan-1 is a marker of endothelial glycocalyx injury.30 31 Established ELISA assays will be used to quantify plasma and serum concentrations of these markers taken at the study time points.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is to observe the cortical and medullary perfusion changes assessed by CEUS parameters (mean transit time, RBV and perfusion index) that occur between those who develop AKI (KDIGO stages 1–3) and those who do not.

Secondary outcomes

To identify if perfusion changes alter by AKI severity, subclassified by KDIGO stages 1–3.

To identify the relationship between renal perfusion variables and biomarker expression.

To identify the presence of renal perfusion variables in patients established on RRT.

To assess the correlation between the sublingual (IDF measured) and renal microcirculations (CEUS).

Analysis of microcirculation images

Video microscopy images will be assessed using AVA 3.2 software (Microvision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to produce the following data:

Total vessel density.

Perfused vessel density.

Microvascular flow index.

Microvascular heterogeneity index.

Analysis of contrast ultrasound images

All videos will be deidentified with respect to patient and time point prior to analysis in order to reduce bias. Regions of interest (ROIs) will be manually drawn: 1 in the renal cortex and 1–2 in the renal medulla. The ROIs for the cortex and medulla will be approximately the same size and depth for every clip. For every ROI, the software determined mean pixel intensities proportional to contrast-agent concentration and created a time–intensity curve (TIC).

Based on the time–intensity wash-in curve, peak enhancement (PE), wash-in area under the curve (WiAUC), rise time (RT), mean transit time (mTT), time to peak (TTP), wash-in rate (WiR) and wash-in perfusion index (WiPI; WiAUC/RT) will be analysed. Parameters related to blood volume are PE and WiAUC. The other parameters, that is, RT, mTT, TTP, WiR and WiPI are related to blood velocity. After wash-in is assessed and steady state is reached (2 min), renal perfusion will be assessed through CEUS replenishment kinetics. Derived variables from the replenishment kinetics include RBV, a measure of maximal contrast intensity after replenishment, the mTT, the time taken from destruction to 50% replenishment and lastly the perfusion index (PI) (RBV/mTT), which is proportional to renal blood flow.

Patient and public involvement

The research question developed from published research priorities by relevant charities and national organisations. We advanced this question and latterly consulted with the Kings College Hospital Renal Patient and Public Involvement Engagement group who highlighted the perceived need for the study and found it to be important and interesting. They found the risk profile to patients to be acceptable and were supportive of its undertaking. We have made changes to the protocol and patient facing documentation based on the feedback we received from this group. Due to the critically ill nature of patients being enrolled in this study, we have not involved patients in the study recruitment, but the conduct has been assessed by patients in the aforementioned process and at the research and ethics committee level. Results of the study will be published through open access but not directly distributed to participants.

Patient identification capacity and consent

In order to assess the microcirculatory changes that occur in septic shock, patients will be recruited to the study early and within 48 hours of admission. A significant proportion of these patients are likely to be intubated and therefore do not have capacity to consent at that time to participate in the study. Guidance stipulated in the Mental Health Act (2005) directs researchers to consult with an individual who has a close relationship with the patient, such as a relative or friend (personal consultee) or in their absence to consult with a clinician involved in the care of the patient (nominated consultee). When capacity is regained, informed consent will be sought from the patient. If the patient refuses, their data will be erased, and no further samples will be taken.

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and will be conducted with the principals of Good Clinical Research Practice (GCP).

The key features of this study are summarised in the WHO Trial Registration Dataset attached in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2018-028364supp001.pdf (56.2KB, pdf)

Confidentiality, data storage and security

The study complies with the principles of the Data Protection Act, 2018. At all times researchers will act to preserve the confidentiality of patient identifiable data. All retained data will be deidentified, that is, stripped of personal identifiable information.

All physical data, such as clinical report forms and consent forms, will be securely stored in a locked research office. All electronic data will be maintained on a secure electronic database accessible only by members of the research team.

Safety

There is one specifically identified safety issue associated with this observational study and that relates to the use of the intravenous contrast agent. This agent consists of a solution of stabilised microbubbles filled with sulphur hexaflouride. The safety profile of this agent is good and has been extensively reported. Postmarketing surveillance provided by the manufacturer of Sonovue reveals use in 2 447 083 patients between 2001 and 2012. Three hundred and twenty-two (0.0162%) serious adverse reactions were reported, although causality was not clearly established in every case. There have been no fatal reactions reported.

Adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) will be reported in the participant’s medical notes, on the study report form, and reported to the principal investigator (PI) within 24 hours. The PI will assess the event for relatedness and expectedness. In the event that the PI decides that the event was related to contrast administration or is unable to positively exclude such an association, the patient will be withdrawn from the study and no further measurements taken. Any SAEs associated with the administration of contrast medium will be reported to the REC in an expedited fashion within 15 days.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data will be examined for normality and then reported as mean±1 SD or median and IQR for normal and non-normal data, respectively. Nominal data will be reported as number and percentage. Differences between groups over time will be assessed using appropriate statistical tests, for example, two-way analysis of variance. Statistical support will be provided from within our institution as necessary. Confounding factors such as nephrotoxic exposure, severity of illness and presence and severity of CKD will be assessed using multivariate analysis.

Discussion

The development of multiorgan dysfunction in sepsis remains incompletely understood despite recent advances in knowledge. AKI as a component of this process was commonly believed to be a result of acute tubular injury and ischaemia from hypotension and subsequent hypoperfusion.32 An intense focus and recent advances by several groups have led to a new understanding of septic AKI as a largely functional phenomenon due to changes in microcirculatory distribution and cellular downregulation.8 9 Currently, the data stem mainly from experimental studies with a growing body of clinical evidence.17 33 Despite this, several questions remain unanswered due to the difficulty in studying renal injury in patients with severe sepsis. As a result, novel approaches are required to delineate the disease process. We believe contrast-enhanced ultrasound, with the capability of studying renal perfusion of both large and small vessels, is such an approach. We hope the data gathered from our study will add to the current understanding and enable future mechanistic research. While this study may identify a correlation, we accept we will not be able to provide evidence of causation, and further studies may be warranted after completion. However, full assessment of renal haemodynamic status may change future management, such as fluid therapy and selection of a specific vasoactive agent. Better identification is needed of patients who require renal replacement therapy and those who may avoid it34 and analysis of renal perfusion may add to this. It is only once we fully understand the disease process can we aim to develop future detection, prevention and treatment of this common and serious complication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Mark McPhail for his statistical support to our project. We would also like to thank the patient advisory group who helped develop our study.

Footnotes

Contributors: JW coauthored the manuscript, is undertaking the investigation and has contributed to the concept. DH is responsible for the radiological input to the study both in concept, writing and training of the investigator(s). KB contributed to the renal aspects of this study, advised on concept and editing of the manuscript. PH contributed to the concept of the study and its evaluation, editing of the manuscript and strategic support. SH is the principal investigator for this study. His involvement includes but is not limited to its design and concept, coauthorship of the manuscript and responsibility for the final editing.

Funding: The study is sponsored by King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The study is funded by the Medical Directorate of the Defence Medical Services, part of the UK Ministry of Defence.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Molina JAD, Seow E, Heng BH, et al. Outcomes of direct and indirect medical intensive care unit admissions from the emergency department of an acute care Hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005553 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005;294:813–8. 10.1001/jama.294.7.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoste EAJ, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1411–23. 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, et al. Septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:431–9. 10.2215/CJN.03681106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouchard J, Acharya A, Cerda J, et al. A prospective international multicenter study of AKI in the intensive care unit. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:1324–31. 10.2215/CJN.04360514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-Term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:961–73. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C, et al. Acute kidney injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:816–28. 10.1007/s00134-017-4755-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calzavacca P, Evans RG, Bailey M, et al. Cortical and medullary tissue perfusion and oxygenation in experimental septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2015;43:e431–9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lima A, van Rooij T, Ergin B, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound identifies microcirculatory alterations in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1284–92. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ince C. Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Crit Care 2015;19(Suppl 3):S8 10.1186/cc14726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Backer D, Donadello K, Sakr Y, et al. Microcirculatory alterations in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2013;41:791–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182742e8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lankadeva YR, Kosaka J, Iguchi N, et al. Effects of fluid bolus therapy on renal perfusion, oxygenation, and function in early experimental septic kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2019;47:e36–43. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, et al. Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2483–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa1101549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrews B, Muchemwa L, Kelly P, et al. Simplified severe sepsis protocol: a randomized controlled trial of modified early goal-directed therapy in Zambia. Crit Care Med 2014;42:2315–24. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada T-aki, et al. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality*. Crit Care Med 2011;39:259–65. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neyra JA, Li X, Canepa-Escaro F, et al. Cumulative fluid balance and mortality in septic patients with or without acute kidney injury and chronic kidney Disease*. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1891–900. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schneider AG, Goodwin MD, Schelleman A, et al. Contrast-Enhanced ultrasound to evaluate changes in renal cortical perfusion around cardiac surgery: a pilot study. Critical Care 2013;17 10.1186/cc12817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Göcze I, Renner P, Graf BM, et al. Simplified approach for the assessment of kidney perfusion and acute kidney injury at the bedside using contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:362–3. 10.1007/s00134-014-3554-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harrois A, Grillot N, Figueiredo S, et al. Acute kidney injury is associated with a decrease in cortical renal perfusion during septic shock. Critical Care 2018;22 10.1186/s13054-018-2067-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalantarinia K, Belcik JT, Patrie JT, et al. Real-Time measurement of renal blood flow in healthy subjects using contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2009;297:F1129–34. 10.1152/ajprenal.00172.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aykut G, Veenstra G, Scorcella C, et al. Cytocam-IDF (incident dark field illumination) imaging for bedside monitoring of the microcirculation. Intensive Care Med Exp 2015;3 10.1186/s40635-015-0040-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Narasimhan M, Koenig SJ, Mayo PH. Advanced echocardiography for the critical care physician: Part 1. Chest 2014;145:129–34. 10.1378/chest.12-2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kidney International Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tejera D, Varela F, Acosta D, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2017;29:444–52. 10.5935/0103-507X.20170061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third International consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). American Medical Association, 2016: 801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wharton G, Steeds R, Allen J, et al. A minimum dataset for a standard adult transthoracic echocardiogram: a guideline protocol from the British Society of echocardiography. Echo Research and Practice 2015;2:G9–G24. 10.1530/ERP-14-0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 2012;120:c179–84. 10.1159/000339789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jia H-M, Huang L-F, Zheng Y, et al. Prognostic value of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in patients at high risk for acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology 2017;22:831–7. 10.1111/nep.13095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang K, Xie S, Xiao K, et al. Biomarkers of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:7 10.1155/2018/6937947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fang Y, Li C, Shao R, et al. The role of biomarkers of endothelial activation in predicting morbidity and mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock in intensive care: a prospective observational study. Thromb Res 2018;171:149–54. 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.09.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naumann DN, Hazeldine J, Midwinter MJ, et al. Poor microcirculatory flow dynamics are associated with endothelial cell damage and glycocalyx shedding after traumatic hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018;84:81–8. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Post EH, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Renal perfusion in sepsis: from macro- to microcirculation. Kidney Int 2017;91:45–60. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, et al. Measurement of renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging during septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1768–76. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246bd85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barbar SD, Clere-Jehl R, Bourredjem A, et al. Timing of renal-replacement therapy in patients with acute kidney injury and sepsis. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1431–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028364supp001.pdf (56.2KB, pdf)