Abstract

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the reference method in screening and diagnosis of colorectal neoplasm, but its efficacy is closely related to the quality of bowel preparation. Poor patient compliance is a major risk factor for inadequate bowel preparation likely due to poor patient education. Such an education is usually provided via either oral or written instructions by clinicians. However, multiple education methods, such as smartphone applications, have been proved useful in aiding patients through bowel preparation. Also, it was reported that a large proportion of patients feel anxious before colonoscopy. Virtual reality (VR) is a novel method to educate patients and provides them with an immersive experience. Theoretically, it can make patients better prepared for bowel preparation and colonoscopy. However, no prospective studies have assessed the role of this novel technology in patient education before colonoscopy. We hypothesise that VR videos can improve bowel preparation quality and reduce pre-procedure anxiety.

Methods/design

The trial is a prospective, randomised, single-blinded, single-centre trial. Outpatients who are scheduled to undergo colonoscopy for screening or diagnostic purposes for the first time will be randomised to receive either the conventional patient education or the conventional methods plus VR videos, and 322 patients will be enrolled from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital. The primary endpoint is the quality of bowel preparation, measured by the Boston bowel preparation score. Secondary endpoints include polyp detection rate, adenoma detection rate, cecal intubation rate, patient compliance to complete bowel cleansing, withdrawal time, pre-procedure anxiety, overall satisfaction and willingness for the next colonoscopy.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the institutional review board of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (No. ZS-1647). The results of this trial will be published in an open-access way and disseminated among gastrointestinal physicians and endoscopists.

Trial registration number

Keywords: colonoscopy, bowel preparation, patient education, virtual reality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a randomised controlled, two-arm, single-blinded trial providing evidence concerning the effectiveness of virtual reality education in improving the quality of bowel preparation and reducing pre-procedure anxiety.

Patients will not bear additional risks in this trial but will possibly have better results of colonoscopy.

This is a single-centre trial.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the reference method in screening and diagnosis of colorectal cancer, and its efficacy is closely related to the quality of bowel preparation, requiring consuming purgatives and restricting diet.1 2 Optimal bowel preparation can lead to a higher adenoma detection rate (ADR).3 However, it has been reported that approximately 30% of patients fail to achieve adequate bowel preparation in Asian patients.4 Inadequate bowel preparation is mainly due to poor patient compliance,5 which closely relates to patient education.6

In most occasions, such education is offered only once through either oral or written instructions by clinicians during an initial appointment. Strong evidence has shown that extensive education methods, including booklet,7 telephone,8 9 message reminders,10 11 smartphone applications,12 13 social media14 and online videos,15–18 have been used to aid patient education with variable effectiveness. These methods can increase patient motivation which can improve bowel preparation quality.19 Also, it has been reported that a large proportion of patients feel anxious before colonoscopy and pre-procedure information help to reduce anxiety.20 Virtual reality (VR) is an interactive computer-generated experience taking place within a simulated environment. It will provide patients with an immersive experience, which is believed to be able to make patients better prepared for both bowel preparation and colonoscopy. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prospective studies have assessed the role of this novel technology in patient education before colonoscopy. We hypothesise that compared with conventional patient education methods, VR videos can improve the quality of bowel preparation through enhancing patient motivation and compliance, reduce pre-procedure anxiety and improve patient experience during conscious colonoscopy.

Methods

Design

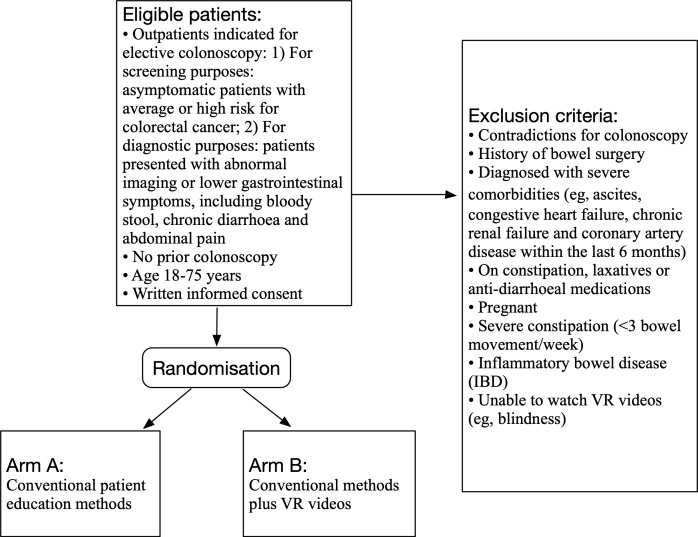

The trial is a prospective, randomised, controlled, single-blinded, single-centre trial. Outpatients who are arranged to undergo a conscious colonoscopy (ie, without sedation) for screening or diagnostic purposes for the first time will be randomised to the control group or the VR intervention group. This study aims to explore whether VR videos can improve bowel preparation quality, increase patient adherence and satisfaction, and reduce pre-procedure anxiety, compared with conventional patient education methods. Figure 1 summarises the design of the trial and each of the trial’s aspects is described in detail below.

Figure 1.

Trial design. VR, virtual reality.

Study population

All patients who have the indications for colonoscopy screening presenting to Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China, will be assessed for eligibility during the appointment, starting from 15 September 2018 and estimated to complete in December 2019.

Inclusion criteria

Outpatients indicated for elective colonoscopy: (1) For screening purposes: asymptomatic patients with average or high risk for colorectal cancer21 and (2) For diagnostic purposes: patients presented with abnormal imaging or lower gastrointestinal symptoms, including bloody stool, chronic diarrhoea and abdominal pain.22

No prior colonoscopy.

Age 18–75 years.

Written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patient who meets any of the following criteria will be excluded:

Contradictions for colonoscopy.

History of bowel surgery.

Diagnosed with severe comorbidities (eg, ascites, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure and coronary artery disease within the last 6 months).

On constipation, laxatives or anti-diarrheal medications.

Pregnant.

Severe constipation (<3 bowel movement/week).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Unable to watch VR videos (eg, blindness).

Randomisation and assignments

After the colonoscopy is scheduled and written informed consent is obtained, patients will be randomised with 1:1 ratio to the conventional education method or the conventional education plus VR video. A computerised random number table will be used in randomisation. The randomisation process is performed by a physician who will also provide education on bowel preparation and will not be involved in performing procedures. All endoscopists in this trial will be unaware of the allocation.

General bowel preparation requirement

Diet restriction: Low-residue diet until the evening on the day before colonoscopy.

-

Colon cleansing regimens:

The first dose: 2 L laxatives (polyethyleneglycol) used on the evening of the day before colonoscopy (after dinner).

The second dose: 1 L laxatives used 3–4 hours before colonoscopy.23

The control group: conventional patient education methods

Patients in the control group will only receive routine patient education on bowel preparation of colonoscopy. A well-trained nurse or a doctor will provide oral instructions on bowel preparation (including definition, significance, correct steps as well as dietary limitations). Written instructions are also provided to patients to take away, which have the same contents as the oral instructions.

The intervention group: conventional methods plus VR videos

In addition to the routine patient education methods mentioned above, patients in the intervention group will watch a VR video using a head-mounted three-dimensional display (figure 2) for about 6 min. Patients will be placed in the simulated settings of an operating room in the VR video. Four parts will be offered, including step by step instructions on bowel preparation, points for attention before and after the procedure, brief introductions to the specific procedures of colonoscopy and a to-do list after a therapeutic procedure (eg, polypectomy). The device can track head movements and patients can familiarise themselves with the operating room and select the part they want to learn with head motion. Patients can only exit when they have finished all these four parts.

Figure 2.

Head-mounted display for virtual reality videos.

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is the quality of bowel preparation measured by the Boston bowel preparation score (BBPS) evaluated during the procedure. In BBPS, three broad regions of the colon (right, including the cecum and ascending colon; transverse, including the hepatic and splenic flexures; and left, including the descending colon, sigmoid and rectum) will be given a score from 0 to 3. A score of 0 means unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that cannot be cleared and 3 means entire mucosa of colon segment seen well with no residual staining, small fragments of stool or opaque liquid. Endoscopists are blinded to the grouping of patients.

Secondary endpoints

We also hypothesise that VR videos can increase patient motivation and deepen their understanding of colonoscopy, which is likely to increase the detection rate of abnormity, reduce anxiety and improve patient experiences. We set secondary endpoints as follows:

Polyp detection rate (PDR).

Adenoma detection rate (ADR).

Cecal intubation rate.

Patient compliance with bowel preparation (rate of complying with diet restriction and laxatives use).

Withdrawal time.

Pre-procedure anxiety (measured by self-rated sleep quality before the procedure).

Overall satisfaction with bowel preparation.

Willingness to take another colonoscopy if indicated.

Sample size calculation

The sample size estimation was based on the test of two independent proportions with a two-sided α=0.05 and a power probability of 90% (β=0.1). The rate of adequate preparation (a score≥2 for all regions) in the control group is 70%,24 and we assumed an increase of 15% for the VR Group. We calculated that at least 161 evaluable patients would be required per group for the study to achieve this power.

Data collection

Data collection will be performed by using a standardised case report form during the appointment and on the day of colonoscopy.

Descriptive statistics

For categorical data, frequencies will be presented. Quantitative data will be presented as the mean and SD or median and IQR. Baseline characteristics (all prior to randomisation) are: age, sex, body mass index, education level, annual personal income, living habits (including smoking, drinking and exercise), dietary habit (vegetarianism/meatatarian/balanced diet), medical history of comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, bronchitis, asthma, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, IBD and malignancy), symptoms (chronic diarrhoea, constipation, mucous stool or bloody stool), family history of colorectal cancer or specific inherited syndromes.

Analyses

All data will be analysed according to the intention-to-treat approach in which all randomised patients are included. Occurrences of the primary and secondary endpoints are compared between the two groups. Results are presented as difference in two proportions. A two-tailed p<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Trial mangement

A steering committee will manage the trial. Screening and recruitment will be reviewed at monthly meetings. An independent data and safety monitoring committee (DSMC) will meet regularly to ensure patient safety and data quality. DSMC will verify all the primary and secondary endpoints as well as at least 10% of data in case report forms against on-site source data. Discrepancies detected by the committee will be resolved through a consensus by two investigators unaware of the study group assignment and not involved in patient care. Relevant clinical and radiological data submitted to the steering committee will facilitate duplicate blinded outcome adjudication.

Termination of the trial

An interim analysis will be conducted on the primary endpoint when 25%, 50% and 75% of patients have been enrolled. The interim analysis is performed by an independent statistician, blinded for the treatment allocation. The statistician will report to the independent DSMC. The DSMC will have unrestricted access to all data and will discuss the results of the intention-to-treat analysis with the steering committee in a joint meeting. The steering committee decides on the continuation of the trial and will report to the central ethics committee. The Peto approach is used to terminate the trial when the intervention group has a significant benefit from the addition of VR to the patient education methods using symmetric stopping boundaries at p<0.001. The trial will not be stopped in case of futility unless the DSMC during safety monitoring advises otherwise. In this case, DSMC will discuss potential stopping for futility with the trial steering committee.

Safety

The DSMC will monitor the progress of the trial by examining safety variables quarterly. This evaluation is based on unblinded data, in the presence of the study coordinator when DSMC requires details of the study. After the full explanation of the data is presented, the study coordinator is dismissed, and the DSMC discusses the consequences of the data presented. Adverse events are defined as ‘any undesirable experience occurring to a subject during a clinical trial, whether or not considered related to the intervention’, such as a sense of dizziness after watching VR videos. All participating physicians will be asked to report any potential adverse events. These adverse events will be listed and discussed with the DSMC. The outcome of the meeting of the DSMC will be discussed with the trial steering committee. The outcome will also be sent to our hospital institutional review board. The DSMC will evaluate the data of the deceased patients for the cause of death, and possible trial-related severe adverse events.

Patients and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the trial design.

Discussions

The trial is aimed to explore whether VR videos can improve bowel preparation quality through increasing patient adherence and experience, and reduce pre-procedure anxiety, compared with the conventional patient education methods. To date, there have been several studies demonstrating that extensive patient education methods7–18 are effective in enhancing bowel preparation quality. However, there is a lack of evidence on the effect of VR videos, a novel technology which can arouse patients’ interests and motivation. Compared with conventional video, VR videos can provide patients with immersive experiences simulating the process of bowel preparation and colonoscopy. The sense of immersion provided by VR videos is believed to be able to reduce the attention distracted by surroundings, which is proved by the fact that VR is used in chronic pain control.25 Thus, it is likely that VR videos can make patients more concentrated in education and enhance the effect of patient education before colonoscopy, leading to better results of the procedure.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YZ is responsible for designing the trial, drafting the protocol, reviewing and final approval. FX contributes to improving the methodology of this trial. XB contributes to the design and reviewing the protocol. AY contributes to the design and managing this trial. DW is the corresponding author, responsible for designing and managing the trial, drafting the protocol, reviewing and final approval.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the U.S. multi-society Task force on colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:543–62. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:781–94. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pontone S, Hassan C, Maselli R, et al. Multiple, zonal and multi-zone adenoma detection rates according to quality of cleansing during colonoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J 2016;4:778–83. 10.1177/2050640615617356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woo DH, Kim KO, Jeong DE, et al. Prospective analysis of factors associated with inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy in actual clinical practice. Intest Res 2018;16:293–8. 10.5217/ir.2018.16.2.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: the importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2010;19:369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenfeld G, Krygier D, Enns RA, et al. The impact of patient education on the quality of inpatient bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24:543–6. 10.1155/2010/718628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spiegel BMR, Talley J, Shekelle P, et al. Development and validation of a novel patient educational booklet to enhance colonoscopy preparation. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:875–83. 10.1038/ajg.2011.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu X, Luo H, Zhang L, et al. Telephone-based re-education on the day before colonoscopy improves the quality of bowel preparation and the polyp detection rate: a prospective, colonoscopist-blinded, randomised, controlled study. Gut 2014;63:125–30. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sondhi AR, Kurlander JE, Waljee AK, et al. A telephone-based education program improves bowel preparation quality in patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2015;148:657–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park J, Kim T-O, Lee N-Y, et al. The effectiveness of short message service to Assure the Preparation-to-Colonoscopy interval before bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015;2015:1–8. 10.1155/2015/628049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walter B, Klare P, Strehle K, et al. Improving the quality and acceptance of colonoscopy preparation by reinforced patient education with short message service: results from a randomized, multicenter study (PERICLES-II). Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Moreno de Vega V, Marín I, et al. Improving the quality of colonoscopy bowel preparation using a smart phone application: a randomized trial. Dig Endosc 2015;27:590–5. 10.1111/den.12467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cho J, Lee S, Shin JA, et al. The impact of patient education with a smartphone application on the quality of bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Clin Endosc 2017;50:479–85. 10.5946/ce.2017.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang SL, Wang Q, Yao J, et al. Effect of WeChat and short message service on bowel preparation: an endoscopist-blinded, randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2018;1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garg S, Girotra M, Chandra L, et al. Improved bowel preparation with multimedia education in a predominantly African-American population: a randomized study. Diagn Ther Endosc 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/2072401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park J-S, Kim MS, Kim H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an educational video to improve quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol 2016;16:64 10.1186/s12876-016-0476-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Back SY, Kim HG, Ahn EM, et al. Impact of patient audiovisual re-education via a smartphone on the quality of bowel preparation before colonoscopy: a single-blinded randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:789–99. 10.1016/j.gie.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pillai A, Menon R, Oustecky D, et al. Educational colonoscopy video enhances bowel preparation quality and comprehension in an inner City population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018;52:515–8. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Serper M, Gawron AJ, Smith SG, et al. Patient factors that affect quality of colonoscopy preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:451–7. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang C, Sriranjan V, Abou-Setta AM, et al. & Singh H. Anxiety Associated with Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2018;59:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:250–81. 10.3322/caac.21457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2015;81:31–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer[J]. Gastroenterology 2014;80:543–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Back SY, Kim HG, Ahn EM, et al. Impact of patient audiovisual re-education via a smartphone on the quality of bowel preparation before colonoscopy: a single-blinded randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:789-799.e4 10.1016/j.gie.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gupta A, Scott K, Dukewich M, et al. Innovative technology using virtual reality in the treatment of pain: does it reduce pain via distraction, or is there more to it? Pain Med 2018;19:151–9. 10.1093/pm/pnx109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.