Abstract

Objective

To explore geographic variations in Irish laparoscopic and open appendectomy procedures.

Design

Analysis based on 2014–2017 administrative hospital data from public hospitals.

Setting

Counties of Ireland.

Participants

Irish residents with hospital admissions for an appendectomy as the principal procedure.

Main outcome measures

Age and gender standardised laparoscopic and open appendectomy rates for 26 counties. Geographic variation measured with the extremal quotient (EQ), coefficient of variation (CV) and the systematic component of variation (SCV).

Results

23 684 appendectomies were included. 77.6% (n= 18,387) were performed laparoscopically. An EQ of 8.3 for laparoscopy and 10.0 for open appendectomy was determined. A high CV was demonstrated with a value of 36.7 and 80.8 for laparoscopic and open appendectomy, respectively. An SCV of 14.2 and 124.8 for laparoscopic and open appendectomy was observed. A wider variation was determined when children and adults were assessed separately.

Conclusions

The geographic distribution in rates of appendectomy varies considerably across Irish counties. Our data suggest that a patient’s likelihood of undergoing a laparoscopic or open appendectomy is associated with their county of residence.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, public health, paediatric surgery, adult surgery, appendicitis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study employed a large, well-defined patient population of Ireland.

All data were age and gender standardised as is standard when analysing geographical variation in healthcare, including the Dartmouth Atlas Project.

The study does not include data from private hospitals, however acute appendicitis is largely managed in public hospitals regardless of medical insurance cover.

Comorbidities, procedural complexity and socioeconomic status were not controlled for when assessing patient characteristics.

Future studies should expand on this study design and additional examination of regional and local variations perhaps in a risk-adjusted setting should be a priority.

Introduction

Acute appendicitis continues to be a global disease with escalating incidence rates in rapidly developing and industrialised countries.1 These epidemiological associations contribute to the evolving knowledge on the pathogenesis of acute appendicitis and the influences of environmental triggers.2 3 Modern advances in laparoscopic surgery over the past two decades have led to the demonstrable advantage of laparoscopic appendectomy over open techniques across all populations.4–6 Laparoscopy is associated with shorter hospital length of stay, decreased analgesic requirements and lower morbidity rates in comparison with open surgery.4 7 8 However, while laparoscopic approaches are preferred in most instances, open appendectomy is still practised in cases where laparoscopy is difficult or contraindicated.

Analysing regional variations in the provision of common procedures helps raise questions relating to service provision as well as identify opportunities for improving efficiency and observing best practice. The Dartmouth Atlas Project has shown wide variations of up to 10-fold for a multitude of surgical procedures across geographical sites in the USA.9 This initiative has led to several studies of geographic variation in other countries which appear to demonstrate that a patient’s likelihood of undergoing specific surgical procedures depends greatly on where they live.10–13 Reasons for the regional variability of laparoscopic and open appendectomy are still unclear. The observed rates of open appendectomy vary widely in the literature from 6% to 35% with higher variations in the adult population.14–16 The aim of this study was to systematically investigate the regional variation of the surgical care of acute appendicitis in Ireland. We compare the national data of laparoscopic and open appendectomy rates for children and adults to provide a current view of regional variation rates. By analysing and comparing the patterns of utilisation of both the adult and paediatric population in Ireland, we seek to understand the extent that area of residence may influence the likelihood of undergoing either a laparoscopic or open procedure.

Methods

Data extraction

Anonymised patient data were obtained for a 4-year period from 2014 to 2017 from the National Quality Assurance and Improvement System (NQAIS). NQAIS is an online application based on the Hospital InPatient Enquiry system (HIPE) operated by the national Health Service Executive in Ireland. Established in 1971, HIPE collects clinical and administrative data on discharges from acute Irish public hospitals. A HIPE record is created following a patient’s discharge from a public hospital and offers demographic and clinical information for the episode of care. The current HIPE system only holds data for public hospitals and no national database is available on the activities in the private hospital sector. This analysis includes only patients treated in public hospitals regardless of their individual insurance status. We obtained records of all hospital episodes coded with laparoscopic appendectomy or open appendectomy as the primary procedure. From this sample, we excluded episodes with primary diagnostic codes different from ‘appendicitis’, ‘suspected appendicitis’ or ‘rule-out appendicitis’ (ie, not coded with K35-37 in the International Classification of Diseases Version 10 Clinical Modification), episodes coded as non-emergency admissions and episodes for patients who are not residents in Ireland.

Ireland is made up of 26 geographical subdivisions referred to as counties. These counties were used in this study to determine appendectomy rates per geographical area. County of residence is a variable in HIPE which can be used to determine residential status of individual persons irrespective of where the actual procedure was performed. We obtained population statistics from the 2016 census from the Central Statistical Office.17

Patient factors considered in the analysis were age, gender and county of residence. Children were categorised as patients aged 14 years or younger to correspond with the 5-year age groups in the available census data. National age and gender stratification was derived from the population of 4 761 865 referred to in the 2016 population census.17

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata V.15.1 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were recorded for patient characteristics and procedure type. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired t-tests. Association of categorical variables (differences for dichotomous variables between groups) was assessed using the Χ2 test. Continuous numerical variables were reported as means and SD. Categorical variables were reported as proportions or percentages.

To assess relative variability we used methods described by McPhearson et al.12 These established methods of geographic variation are widely used in small-area variation studies and allow for context and comparison across geographical settings and countries.13 18 19 The extremal quotient (EQ) is presented as the ratio of the highest and lowest standardised county rate. A value close to 1 indicates low variation in rates across counties. The coefficient of variation (CV) is a measure of relative variability and is calculated as the SD of the county rates divided by the mean of county rates. A value >0.3 is considered ‘highly variable’ in accordance with the studies by McPhearson et al with higher scores indicating greater variability.12 20 The systematic component of variation (SCV) is also a measure of variation. This is the difference between the random component of variation and the total variation. Homogeneity in rates between areas would result in a value of zero. A large SCV value indicates large systematic and regional variation.12 We estimated these variability measures for the whole population and for children and adults separately.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the development of design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results.

Results

National analysis

A total of 26 760 episodes of care discharged through 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2017 were extracted. In this sample, 1902 episodes were coded with diagnoses other than K35-K37; 885 episodes were coded as non-emergency admissions; 289 episodes related to non-Ireland residents. After exclusion of these episodes, our study sample included 23 684 episodes of care of which 77.6% were laparoscopic appendectomies and 22.4% were open appendectomies; 53.7% of patients were male and the mean age was 25 years (SD 15, median 20, range 0–98). These findings are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Number of adult and paediatric laparoscopic and open appendectomy

| Laparoscopic (n (%)) | Open (n (%)) | Total (n (%)) | P value | |

| Children (n=7343) | ||||

| Male | 2068 (49.1%) | 2140 (50.9%) | 4208 (100%) | |

| Female | 1790 (57.1%) | 1345 (42.9%) | 3135 (100%) | <0.01 |

| Adult (n=16 341) | ||||

| Male | 7387 (86.8%) | 1126 (13.2%) | 8513 (100%) | |

| Female | 7142 (91.2%) | 686 (8.8%) | 7828 (100%) | <0.01 |

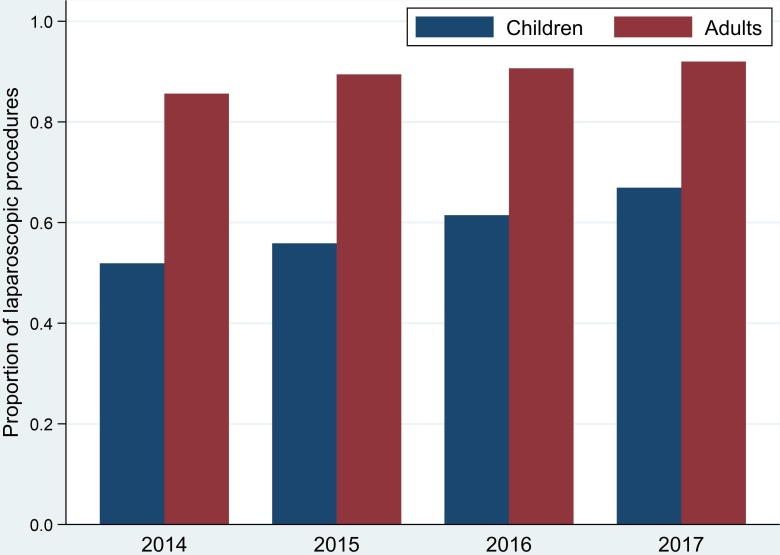

The percentage of laparoscopic procedures was 52.6% among children and 88.9% among adults (statistically significant difference; OR 7.2 95% CI 6.8 to 7.7). Figure 1 displays the proportion of appendectomies conducted as laparoscopic procedures for 2014 to 2017 in children and adult patients. The proportion of laparoscopic procedures increased steadily during the studied years 2014–2017 from 72.7% to 83.3% (trend p<0.01). For children the proportion increased from 43.9% to 61.4% (trend p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Proportion of appendectomies conducted as laparoscopic procedures during 2014–2017 in children and adult patients.

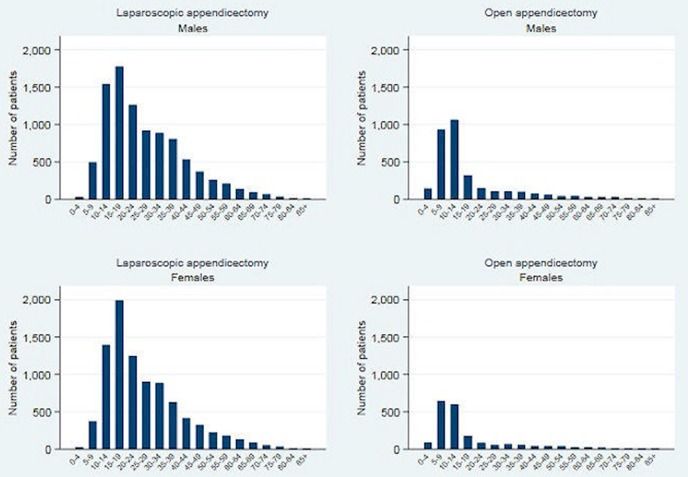

Girls were more likely to have laparoscopic procedures than boys (57.1% vs 49.1%, OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.5), and women more likely than men (91.2% vs 86.8%, OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.4 to 1.8). A clear age gradient was observed when comparing laparoscopic and open appendectomy procedures for the whole population and for both men and women separately (figure 2) (OR 1.016, 95% CI 1.013;1.020) The proportion of patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures reduced for older patients in both genders (logistic regression p<0.01) and appears statistically lower for patients older than 45 years (p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Age and gender distribution for laparoscopic and open appendectomy.

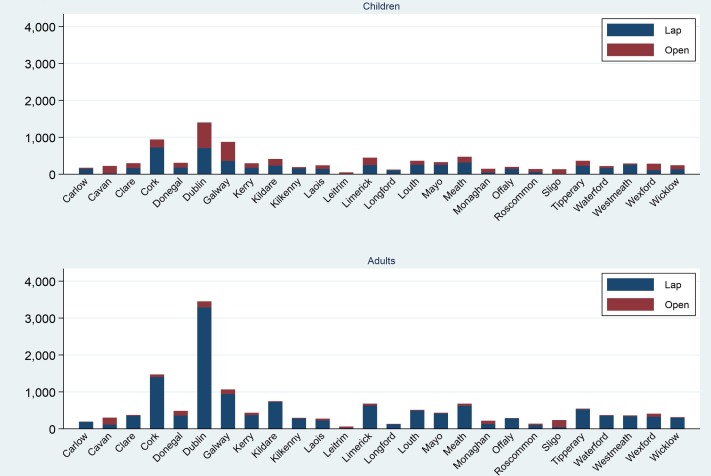

County analysis

Figure 3 displays the number of laparoscopic and open procedures performed on children and adults during the years 2014–2017 by county of residence. The annual appendectomy rate was estimated at 124.4 procedures per 100 000 persons and 96.5 and 27.8 for laparoscopic and open approaches, respectively. The online supplementary table shows the proportion of laparoscopic appendectomies per year by county of residence for the child and adult population. The data display a gradual increase in the number of laparoscopic procedures performed in both patient groups during the 4-year study period.

Figure 3.

Number of procedures performed during 2014–2017 on county residents.

bmjopen-2018-025231supp001.pdf (122KB, pdf)

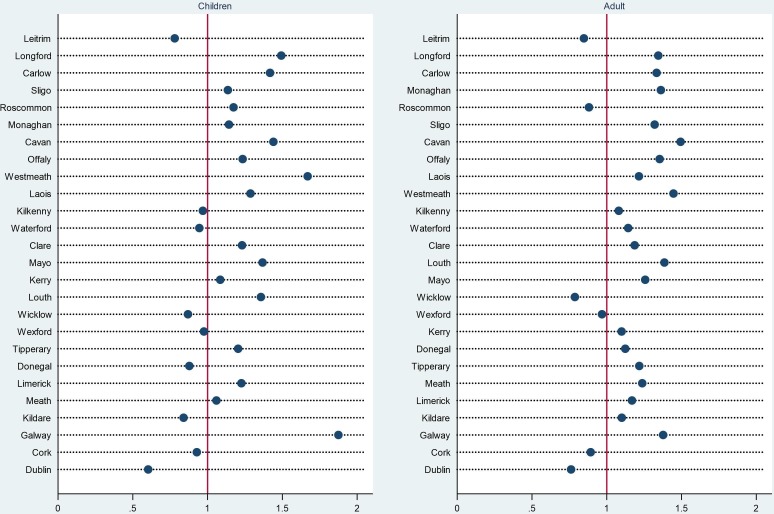

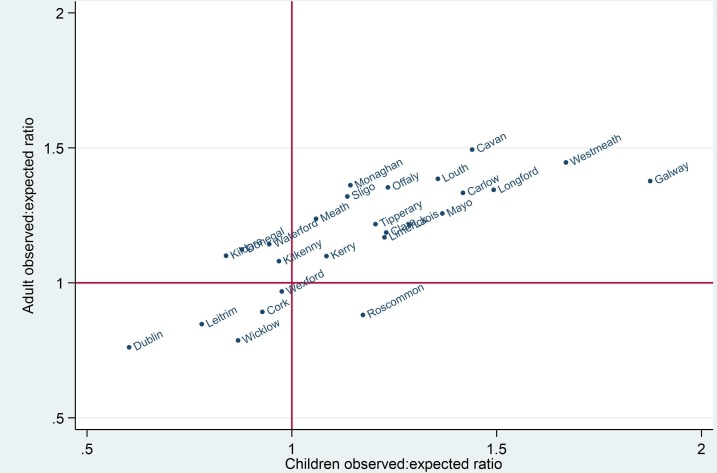

Figure 4 presents the ratio of the observed and expected number of the total appendectomy rates within different counties for both children and adults and displays the geographic dispersions determined. The expected number of procedures was estimated by relating the national age and gender procedure rate to the county population and demonstrates the intercounty discrepancies in a risk-adjusted setting. A value of 1 was determined to be the national average rate to allow for comparison between geographic areas. The ratio takes a value larger than 1 when the numbers of observed procedures are higher than the expected number of procedures. This would indicate a high volume county when compared with the national average value. For children, 17/26 counties displayed a higher than average rate of appendectomy procedures. For the adult population, residents from 20/26 counties underwent appendectomy procedures at a higher rate than the national average.

Figure 4.

Ratio of observed/expected number of episodes of appendectomy by county for children and adults.

Figure 5 presents the association between the ratio of observed and expected procedures for children and adults. Counties in the north-east quadrant have a higher than expected number of procedures for both children and adults. These counties demonstrate higher rates of appendectomy procedures for their entire populations. There appears to be a strong association between the ratio for children and adults indicating that counties with a higher ratio for children also have a higher ratio for adults. Counties in the south-west quadrant have a lower than expected number of procedures for both children and adults. Using similar reasoning, counties with lower rates of paediatric appendectomy procedures appeared to have low rates for the adult population also. Only four counties have a different pattern. Roscommon is the only county where children have more than the expected episodes of care and adults have fewer than the expected episodes of care, while the reverse appears for Kilkenny, Waterford, Donegal and Kildare. These remaining four counties display high rates in the adult population but lower than average rates in the paediatric patient group.

Figure 5.

Association between children’s and adult’s ratio of observed/expected number of episodes of appendectomy by county.

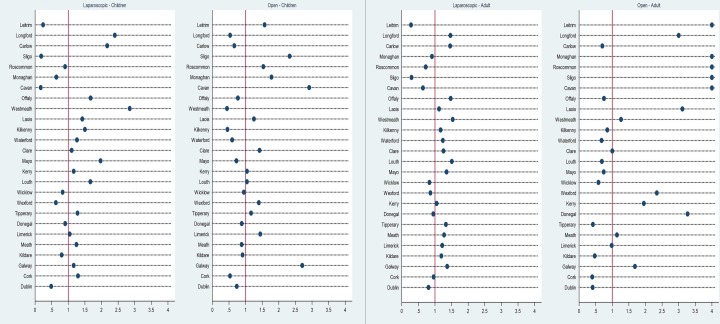

Figure 6 displays the ratio of observed and expected procedures for laparoscopic and open procedures for children and adults separately. Wide population dispersions are demonstrated in children for both laparoscopic and open appendectomy. In 16/26 counties, children underwent laparoscopic appendectomy at rates higher than the national average, indicating areas with high utilisation. Children from 13/26 counties underwent higher rates of open appendectomy procedures than the rest of the general population. Similarly, adults in 16/26 counties had higher rates of laparoscopic procedures than the rest of the national population, and adults from 12/26 counties underwent higher rates of open appendectomy procedures. Wide dispersions are particularly evident in the adult population with open appendectomy.

Figure 6.

Ratio of observed/expected number of episodes of laparoscopy and open appendectomy by county for children and adults.

Table 2 displays the statistical measures of variation for the combined population and children and adults separately. The EQ was 8.3 for laparoscopic and 10.0 for open appendectomy, demonstrating greater geographic variation for open appendectomy. The CV was high for both laparoscopic and open appendectomy; 36.7 for laparoscopic and 80.8 for open procedures, in accordance with the McPhearson et al interpretations.12 This demonstrates greater geographic variability in the application of open appendectomy cases. The SCV was also high for both procedures; 14.2 for laparoscopy and 124.8 for open appendectomy.

Table 2.

Variation statistics for laparoscopy, open and combined for children, adult and the whole patient population, 2014–2017

| Population/procedure | Number of episodes 2014–2017 |

Standardised number of episodes per 100 000 population |

EQ | CV | SCV |

| Children | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 3858 | 383.3 | 16.9 | 55.1 | 41.6 |

| Open | 3485 | 346.2 | 6.5 | 55.3 | 38.2 |

| Combined | 7343 | 729.5 | 3.2 | 24.3 | 9.3 |

| Adult | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 14 529 | 386.9 | 7.1 | 33.3 | 10.6 |

| Open | 1812 | 48.3 | 25.7 | 128.4 | 502.0 |

| Combined | 16 341 | 435.1 | 2.1 | 18.9 | 4.5 |

| Whole population | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 18 387 | 386.1 | 8.3 | 36.7 | 14.2 |

| Open | 5297 | 111.2 | 10.0 | 80.8 | 124.8 |

| Combined | 23 684 | 497.4 | 2.2 | 19.6 | 5.6 |

EQ=max(standardised episode rate i)/min(standardised episode rate i).

CV=SD (standardised episode rate i)/mean (standardised episode rate i)×100.

SCV=1/k (∑(Oi–Ei)2/Ei 2–∑1/Ei)×100, where k is number of counties, Oi is observed number of episodes and Ei is expected number of episodes determined by indirect standardisation.

CV, coefficient of variation; EQ, extremal quotient; SCV, systematic component of variation.

Discussion

This study documents a substantial geographic variation in the operative management of acute appendicitis in Ireland. To our knowledge, there have been no population-based studies exploring emergency appendectomy variations at a county level in Ireland. While some level of disparity is to be expected, large variations particularly in emergency interventions can indicate potential inequity and inefficiency in the use of sophisticated healthcare systems, and thus indicate variations in access and use of surgical services. Similar to the Dartmouth Atlas project, our data demonstrates that a person’s likelihood of undergoing a laparoscopic or open appendectomy is related to their county of residence.9

Laparoscopic appendectomy is favoured because of its benefits in analgesic requirements postoperatively, shorter length of hospital stay, lower postoperative mortality and faster return to normal activities.4 7 8 21 22 Unsurprisingly, most of the cases in our data were performed laparoscopically. As with most observational data, causality cannot be determined. Historical research suggests that the variations in the utility of surgical services may result from clinical uncertainty or heterogeneity in medical literature.23 24 One potential hypothetical and important reason for the variations could be individual surgeon skill and practice. The current study did not control for specific surgeon factors and may reflect a lack of laparoscopic skills or capacity in certain areas and explain the higher statistical variability for open procedures. Variations in laparoscopic surgery rates are not unheard of. An analyses by Doumouras et al suggested that laparoscopic training may influence the rate of laparoscopic practices in some hospitals.25 While our study did not evaluate larger teaching hospitals separately, there may be an inherent geographic variation in laparoscopic expertise outside of tertiary referral centres and may also reflect variation in consultant and trainee surgeon performance as the principal operator, a factor not examined in this study.

In this study, laparoscopic appendectomy utilisation appears lower in children and may indicate a deficiency in the paediatric surgery skillset available in the country and an unfamiliarity in operating on children among general surgeons. Multiple reports have stressed the need to provide high-quality paediatric surgery services to address the challenges and demands of paediatric patients, which may be unavailable in hospitals were adult surgery appears to dominate. The findings of this study suggest a potential difference in expertise in relation to paediatric surgery in Ireland. This would parallel with the reality that most district or general hospitals in Ireland lack a specialised paediatric surgeon on site and thus cases are performed by adult surgeons. These findings suggest a potential difference in expertise in relation to paediatric surgery in Ireland.

There are some limitations to this study. As with other studies including data from administrative databases, the reliability of results is based on the accuracy and completeness of systematic coding and data input. We attempt to overcome potential miscoding information by including a large population cohort of patients over a 4-year period. We have not accounted for laparoscopic cases that were converted to open due to the potential inclusion of duplicate numbers and inherent miscoding errors. Comorbidities, procedural complexity and socioeconomic status were also not controlled for when assessing patient characteristics. However, despite these limitations our findings demonstrate concerning conclusions relating to the provision of emergency appendectomy in Ireland for both children and adults. The analysis provides some important implications for healthcare providers and surgeons in analysing the extent of geographic variation and the disparity in management of a common condition. While we cannot explain the wide variations seen, further analysis at an individual county level with the assessment of more in-depth patient characteristics may uncover opportunities to eliminate variations and ultimately improve the delivery of care and patient outcomes. We also await the results of the multi-institutional Right Iliac Fossa (RIF) Treatment study to further analyse the variation in the management strategies of patients presenting with RIF pain to centres across the UK, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.26

Conclusion

Geographic variation analyses can help characterise the overall performance of a health system and determine whether patients receive equal treatment for equal needs. This is the first Irish study to systematically explore the rates and geographical disparity of acute laparoscopic and open appendectomy procedures and help bridge a pre-existing knowledge gap on the topic. The high appendectomy rates seen in several counties in this study may suggest an imbalance in the provision of a common acute surgical procedure in Ireland. Some populations appear more likely to undergo laparoscopic procedures than other populations with considerable geographical disparity observed within a relatively small country. Large statistical variability in the paediatric population may also reflect a discrepancy in surgical paediatric care in areas where these procedures are largely performed by surgeons specialising in adult care. Based on these results, we recommend future studies to focus on the practicality of this and further analysis into the structure of emergency paediatric surgery, particularly in district hospitals. Despite the limitations, our study suggests a need for more effective decision-making and planning to ensure consistency and decrease the variability in the management of acute appendicitis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Healthcare Pricing Office as the source of Hospital InPatient Enquiry (HIPE) data, which is used in the National Quality Assurance and Improvement System (NQAIS) Clinical. The authors also acknowledge the Clinical Leads of the National Clinical Programme in Surgery, the NQAIS Clinical Steering Group, the HORC-NCP research group and the Acute Hospital Division (HSE) for providing access to NQAIS Clinical.

Footnotes

Contributors: OA conceived and designed the study, analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. JS designed the study, prepared and analysed the data, drafted and revised the paper. KM interpreted the results and revised the paper. All authors had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. OA is the guarantor and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics board approval was not required for the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Ferris M, Quan S, Kaplan BS, et al. The global incidence of appendicitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Ann Surg 2017;266:237–41. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan GG, Dixon E, Panaccione R, et al. Effect of ambient air pollution on the incidence of appendicitis. Can Med Assoc J 2009;181:591–7. 10.1503/cmaj.082068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan GG, Tanyingoh D, Dixon E, et al. Ambient ozone concentrations and the risk of perforated and nonperforated appendicitis: a multicity case-crossover study. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121:939–43. 10.1289/ehp.1206085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tate JJT, Dawson JW, Chung SCS, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy: prospective randomised trial. The Lancet 1993;342:633–7. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91757-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Southgate E, Vousden N, Karthikesalingam A, et al. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in older patients. Arch Surg 2012;147:557–62. 10.1001/archsurg.2012.568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adwan H, Weerasuriya CK, Endleman P, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy in children: a UK district general Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:277–9. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomson J-E, Kruger D, Jann-Kruger C, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for complicated appendicitis: a randomized controlled trial to prove safety. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2027–32. 10.1007/s00464-014-3906-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tiwari MM, Reynoso JF, Tsang AW, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic and open appendectomy in management of uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis. Ann Surg 2011;254:927–32. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822aa8ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Practice TDIoHPaC The Dartmouth atlas project database 1996 - 2010.

- 10. Reames BN, Shubeck SP, Birkmeyer JD. Strategies for reducing regional variation in the use of surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2014;259:616–27. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahmed O, Mealy K, Kelliher G, et al. Exploring geographical variation in access to general surgery in Ireland: evidence from a national study. Surgeon 2019;17 10.1016/j.surge.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McPherson K, Wennberg JE, Hovind OB, et al. Small-area variations in the use of common surgical procedures: an international comparison of new England, England, and Norway. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1982;307:1310–4. 10.1056/NEJM198211183072104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weeks WB, Paraponaris A, Ventelou B. Geographic variation in rates of common surgical procedures in France in 2008-2010, and comparison to the US and Britain. Health Policy 2014;118:215–21. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katsuno G, Nagakari K, Yoshikawa S, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a comparison with open appendectomy. World J Surg 2009;33:208–14. 10.1007/s00268-008-9843-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the nationwide inpatient sample (NIS), 2006-2008. J of Surg 2011;15:2226–31. 10.1007/s11605-011-1613-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Litz CN, Ciesla DJ, Danielson PD, et al. Effect of hospital type on the treatment of acute appendicitis in teenagers. J Pediatr Surg 2018;53:446–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scoreboard MIP. Central statistics office statistical release, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Appleby J, Raleigh V, Frosini F, et al. Variations in health care: the good, the bad and the inexplicable. King's Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, et al. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. The Lancet 2013;382:1121–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chassin MR, Brook RH, Park RE, et al. Variations in the use of medical and surgical services by the Medicare population. N Engl J Med 1986;314:285–90. 10.1056/NEJM198601303140505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;23 10.1002/14651858.CD001546.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Faiz O, Clark J, Brown T, et al. Traditional and laparoscopic appendectomy in adults: outcomes in English NHS hospitals between 1996 and 2006. Ann Surg 2008;248:800–6. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818b770c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ray-Coquard I, Philip T, Lehmann M, et al. Impact of a clinical guidelines program for breast and colon cancer in a French cancer center. JAMA 1997;278:1591–5. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550190055044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wennberg JE. Dealing with medical practice variations: a proposal for action. Health Aff 1984;3:6–33. 10.1377/hlthaff.3.2.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doumouras AG, Saleh F, Eskicioglu C, et al. Neighborhood variation in the utilization of laparoscopy for the treatment of colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:781–8. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nepogodiev D, RIFT Study Group On behalf of the West Midlands Research Collaborative . Right iliac fossa pain treatment (Rift) study: protocol for an international, multicentre, prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017574 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025231supp001.pdf (122KB, pdf)