Abstract

Cancer-associated systemic inflammation is strongly linked with poor disease outcome in cancer patients1,2. For most human epithelial tumour types, high systemic neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios are associated with poor overall survival3, and experimental studies have demonstrated a causal relationship between neutrophils and metastasis4,5. However, the cancer cell-intrinsic mechanisms dictating the substantial heterogeneity in systemic neutrophilic inflammation between tumour-bearing hosts are largely unresolved. Using a panel of 16 distinct genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) for breast cancer, we have uncovered a novel role for cancer cell-intrinsic p53 as a key regulator of pro-metastatic neutrophils. Mechanistically, p53 loss in cancer cells induced secretion of Wnt ligands that stimulate IL-1β production by tumour-associated macrophages, which drives systemic inflammation. Pharmacological and genetic blockade of Wnt secretion in p53-null cancer cells reverses IL-1β expression by macrophages and subsequent neutrophilic inflammation, resulting in reduced metastasis formation. Collectively, we demonstrate a novel mechanistic link between loss of p53 in cancer cells, Wnt ligand secretion and systemic neutrophilia that potentiates metastatic progression. These insights illustrate the importance of the genetic makeup of breast tumours in dictating pro-metastatic systemic inflammation, and set the stage for personalized immune intervention strategies for cancer patients.

To determine how pro-metastatic systemic inflammation is influenced by genetic aberrations in tumours, we studied 16 GEMMs for breast cancer carrying different tissue-specific mutations. These GEMMs represent most subtypes of human breast cancer, including ductal and lobular carcinoma, oestrogen receptor-positive (luminal A), HER2+, triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer. Because we and others have demonstrated that neutrophils expand systemically and promote metastasis5–10, we evaluated circulating neutrophil levels as a marker for systemic inflammation in mammary tumour-bearing mice with end-stage disease. As expected, most tumour-bearing mice displayed an increase in circulating neutrophils as compared to non-tumour-bearing animals (wild-type [WT]) (Fig. 1a). Like the inter-patient heterogeneity in systemic inflammation in human breast cancer11, we observed a striking variability in the extent of neutrophilia between the different tumour-bearing GEMMs (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a). We found that the models exhibiting high neutrophil expansion displayed a subset of neutrophils expressing the stem cell marker cKIT (Fig. 1b), indicative of an immature neutrophil phenotype5. We subsequently searched for commonalities and differences among the 16 GEMMs with regards to high versus low systemic neutrophil levels. Strikingly, mice bearing tumours with a p53 deletion exhibited the most pronounced circulating neutrophil levels (Fig. 1a). The difference in magnitude of systemic inflammation between p53-proficient and p53-null tumours was even more apparent when focusing on cKIT+ neutrophils (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Loss of p53 in mammary cancer cells correlates with systemic neutrophilic inflammation.

a. Flow cytometry analysis of frequency of CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ neutrophils and b. proportion of cKIT+ neutrophils as determined by flow cytometry analysis on blood of breast cancer GEMMs at end-stage (cumulative tumour volume 1500 mm3) and non-tumour-bearing (WT) controls (n=4, 3, 4, 7, 3, 4, 4, 3, 6, 7, 6, 9, 3, 5, 4, 7 and 7 mice, top to bottom). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to WT. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001. c. Total neutrophil frequencies and d. cKIT+ neutrophil frequencies in circulation of all Trp53+/+ (n=28) and Trp53–/– (n=46) tumour-bearing mice, combined from a. and b. e. CCL2 levels (n=17 Trp53+/+, n=22 Trp53–/–), f. IL-1β levels (n=18 Trp53+/+, n=21 Trp53–/–), g. IL-17A levels (n=24 Trp53+/+, n=30 Trp53–/–) and h. G-CSF levels (n=22 Trp53+/+, n=33 Trp53–/–) in serum of GEMMs at end-stage based on p53 status. i. Principal component analysis of data depicted in a – h (13 out of 16 GEMMs). Each symbol represents one mouse. Circles contour 40% of group-specific Gaussian probability distributions of sample scores. All data are means ± s.e.m., P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple-testing correction (a, b) or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (c – h).

In mouse models for colorectal, pancreatic, prostate and endometrial cancer, p53 mutation or loss leads to recruitment and activation of immune cells in the primary tumour microenvironment12–16. To study the association between p53 status of the tumour and systemic inflammation, we separated the 16 GEMMs based on the presence or absence of homozygously floxed Trp53 alleles and compared the levels of circulating neutrophils and the proportion of cKIT-expressing neutrophils. This analysis confirmed a statistically significant difference between mice bearing p53-proficient and p53-null tumours (Fig. 1c, d).

We previously demonstrated that expansion of neutrophils in mammary tumour-bearing K14-cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F (KEP) mice is driven by an inflammatory pathway involving CCL2, IL-1β, IL-17A and G-CSF5,17. We found that serum levels of CCL2, IL-1β and G-CSF correlated with p53 loss in primary tumours in the 16 GEMMs (Fig. 1e–h). Principal component analysis of these systemic immune parameters further demonstrated that systemic inflammation correlated with p53 status of the tumour (Fig. 1i).

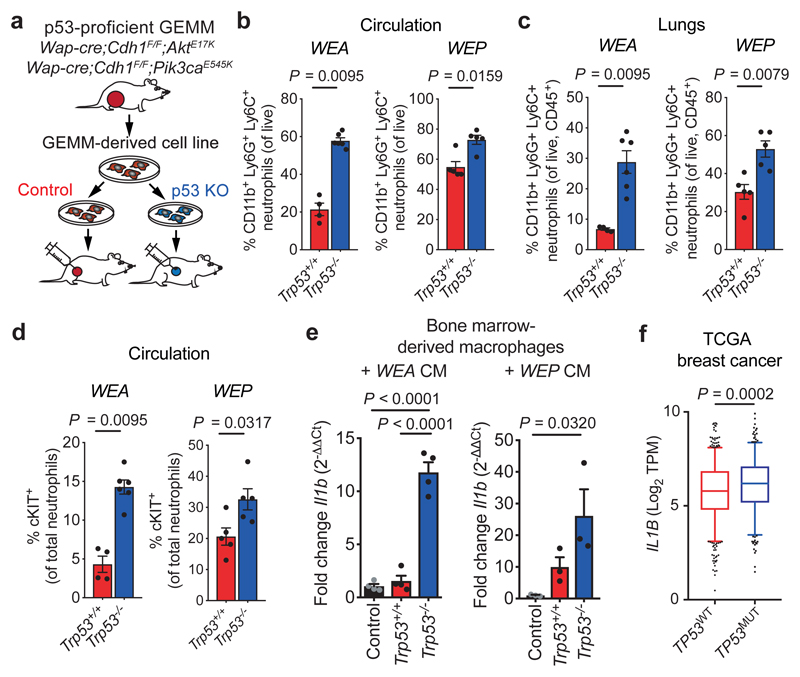

To provide evidence for a causal relationship between p53-loss in mammary tumours and neutrophilia, we derived cancer cell lines from two independent p53-proficient tumour models, Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K (WEA)18 and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP). Using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption, we targeted Trp53, which resulted in an inability to increase p21 levels after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b, e). We orthotopically transplanted WEA;Trp53+/+ and WEP;Trp53+/+ cells, and matched WEA;Trp53–/– and WEP;Trp53–/– cells into syngeneic WT mice (Fig. 2a). While p53-loss conferred a proliferation advantage in vitro, in vivo growth kinetics were similar between p53-proficient and -deficient tumours for both cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 2c–g). Consistent with our findings in the GEMM panel, we observed increased expansion of neutrophils, including cKIT+ neutrophils, in the circulation and lungs of mice bearing WEA;Trp53–/– and WEP;Trp53–/– tumours, when compared to mice bearing size-matched p53-proficient tumours (Fig. 2b–d, Extended Data Fig. 2h, i). In addition, mice with WEA;Trp53–/–, but not WEP;Trp53–/– tumours, presented with splenomegaly when compared to Trp53+/+ controls (Extended Data Fig. 2j), a phenomenon often observed in inflammation and cancer19. These data reveal that loss of p53 in breast cancer cells is a central driving event of cancer-induced systemic neutrophilic inflammation.

Figure 2. p53 status in mammary tumours dictates immune activation.

a. Experimental setup: cell lines are derived from Trp53+/+ tumours (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K (WEA) and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP)) and p53 is knocked out (KO) using CRISPR/Cas9. KO and control cell lines are orthotopically transplanted into syngeneic mice. b. Frequency of total CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ neutrophils in circulation and c. in lungs, and d. frequency of cKIT+ neutrophils (% of total neutrophils) in circulation at end-stage (tumour volume 1500 mm3) of mice with Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– WEA and WEP tumours, as determined by flow cytometry (n=4 WEA;Trp53+/+, n=6 WEA;Trp53–/–, n=5 WEP;Trp53+/+, n=5 WEP;Trp53–/–). e. RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of Il1b in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) after exposure to conditioned medium from Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– WEA (n=4 biological replicates/group) or WEP cell lines (n=3 biological replicates/group). Plots show representative of 3 independent experiments with 2 technical replicates per biological replicate. f. IL1B expression in TP53 wild-type (WT, n=643) or TP53 mutant (MUT, n=351) human breast tumours of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Data in b – e are means ± s.e.m., f. shows 5 – 95 percentile boxplot with median and quartiles indicated. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (b, c, d, f) or two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple-testing correction (e).

Since we observed cKIT+ immature neutrophils in p53-null tumour-bearing mice (Fig. 1d, 2d), we next investigated whether haematopoiesis was altered. In mice bearing WEA;Trp53–/– tumours, frequencies of Lin—Sca1+cKIT+ cells (LSKs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), CD11b+Ly6Glow pro-myelocytes and mature neutrophils were increased in the bone marrow at the expense of megakaryocyte and erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs), when compared to WEA;Trp53+/+ tumour-bearing mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). This effect on cell proportions was not reflected in the total cell counts, possibly due to a slight depletion of total bone marrow cell numbers in WEA;Trp53–/– tumour-bearing mice (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

Previously, we reported that macrophage-derived IL-1β in the tumour microenvironment triggers systemic neutrophil expansion in KEP mice5. Since IL-1β serum levels correlated with p53 status (Fig. 1f) we hypothesized that loss of p53 changes the secretome of cancer cells, stimulating IL-1β production from tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) and setting off a systemic inflammatory cascade. Indeed, in vitro exposure of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) to conditioned medium (CM) from WEA;Trp53–/– or WEA;Trp53+/+ cancer cells differentially affected their phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Notably, CM from WEA;Trp53–/– and WEP;Trp53–/– cells strongly induced Il1b mRNA expression in cultured BMDMs as compared to CM from matched Trp53+/+ controls (Fig. 2e). In agreement with our mouse data, human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) cultured with tumour CM of TP53–/– MCF-7 human breast cancer cells displayed increased CD206 and CD163 expression compared to hMDMs cultured with CM of p53-proficient MCF-7 cells (Extended Data Fig. 4c). We also observed increased IL1B expression in hMDMs upon exposure to TP53–/– MCF-7 cells compared to TP53+/+ controls (Extended Data Fig. 4d). These data indicate that cancer cell-intrinsic p53 status dictates the crosstalk between cancer cells and macrophages in a paracrine fashion, resulting in an altered macrophage phenotype and IL-1β production. We also observed elevated levels of IL1B mRNA expression in breast tumours of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) with mutations in TP53 (TP53MUT) compared to TP53WT tumours (Fig. 2f), suggesting similar p53-dependent activation of IL-1β signalling in human breast cancer.

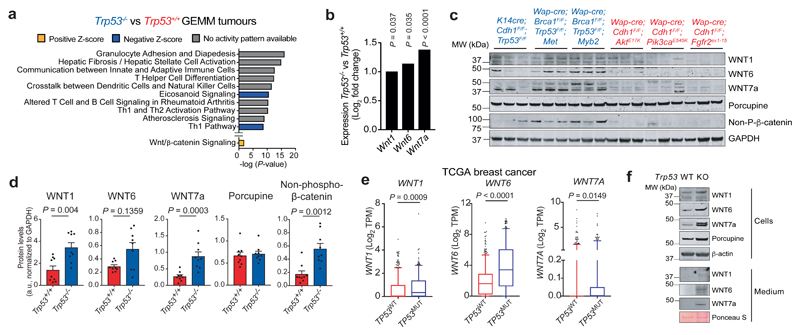

To identify which factor(s) in p53-null tumours mediate TAM activation and subsequent systemic inflammation, we performed RNA sequencing on mammary tumours of 12 different GEMMs (7 p53-null models, 5 p53-proficient models; 145 tumours in total). The p53-deficient tumours differed substantially from p53-proficient tumours in terms of gene expression, regardless of any additional genetic aberrations, demonstrating a dominant effect of p53-loss on the global transcriptome (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the most significantly changed pathways in p53-deficient tumours pertained to adaptive immune phenotypes (Fig. 3a). While neutrophil and TAM numbers were altered intratumourally, the composition of CD8+, CD4+ or FOXP3+ T cells did not correlate with p53-status (Extended Data Fig. 5b–g), suggesting that the distinct transcriptome profiles are not due to a p53-dependent effect on the composition of the adaptive immune landscape.

Figure 3. p53-null tumours display activated Wnt signalling.

a. Top 10 most significantly differentially activated pathways determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, comparing Trp53–/– (n=77) with Trp53+/+ (n=68) GEMM tumours of 12 different models. Also indicated is the Wnt signalling pathway. b. Log2 fold change expression of Wnt1, Wnt6 and Wnt7a in Trp53–/– (n=77) GEMM tumours compared to Trp53+/+ (n=68) tumours. c. Western blot analysis of bulk tumours showing non-phospho(active)-β-catenin, Porcupine, WNT1, WNT6 and WNT7a (blue indicates Trp53–/– tumours and red indicates Trp53+/+ tumours). Representative of two independent experiments. For uncropped images, see Supplemental Fig. 1. d. Quantification of c (n=3/group). e. Expression of WNT1, WNT6 and WNT7A in TP53 wild-type (WT, n=643) and TP53 mutant (MUT, n=351) human breast tumours of TCGA breast cancer database. f. Western blot analysis on cell lysate and conditioned medium of Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53+/+ (WT) and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53–/– (KO) cell lines for Wnt ligands. Representative of two independent experiments. d. shows mean ± s.e.m., e shows 5 – 95 percentile boxplot with median and quartiles indicated. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, FDR multiple-testing correction (b) or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (d, e).

From the gene ontology analysis, we selected genes encoding secreted factors that could potentially influence TAMs. One of the up-regulated pathways in p53-null tumours included Wnt/β-catenin signalling (Fig. 3a). Wnt signalling is linked to IL-1β production in acute arthritis, as well as immune and stromal signalling in cancer20–23. Using a Wnt/β-catenin signalling gene signature, we found that p53-null GEMM tumours clustered separately from p53-proficient tumours, indicating an association between p53-loss and Wnt-related gene expression (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Many Wnt-related genes were up-regulated in p53-deficient tumours, including three Wnt ligands, Wnt1, Wnt6 and Wnt7a, while expression of negative regulators of Wnt signalling was decreased (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 6c). Elevated protein levels of WNT1 and WNT7A were confirmed in a set of independent p53-deficient tumours (Fig. 3c, d). We also found increased expression of non-phosphorylated β-catenin, indicative of activated Wnt signalling (Fig. 3c, d). In human breast tumours, expression of WNT1, WNT6 and WNT7A was increased upon aberrant expression of TP53, compared to TP53WT tumours (Fig. 3e). We then broadened our analysis of TCGA data to other WNT-related genes and discovered a trend towards enrichment of these genes in TP53-mutated tumours (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Additionally, individual WNT-stimulating genes were upregulated, while WNT-inhibiting genes were downregulated in TP53MUT versus TP53WT human tumours (Extended Data Fig. 6e), indicating that WNT signalling is activated upon aberrant expression of TP53. Using WEA cell lines, we confirmed that WNT1, WNT6 and WNT7A proteins are increased intracellularly in WEA;Trp53–/– cells and secreted, when compared to WEA;Trp53+/+ cells (Fig. 3f). Collectively, these data indicate cancer cell-autonomous Wnt ligand secretion upon loss of p53.

Since deletion of p53 increases Wnt ligand expression, we hypothesized that wild-type p53 negatively regulates these genes, either directly or indirectly. To determine whether p53 binds the regulatory regions of Wnt1, Wnt6 and/or Wnt7a, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) in 3 independent WEA and WEP cell lines. p53 binding was observed at the Cdkn1a (p21) locus (Extended Data Fig. 7a), whereas we did not find p53 binding at the Wnt1, Wnt6 or Wnt7a loci (Extended Data Fig. 7b), suggesting that p53 regulates their expression indirectly. Since p53 has been described to control Wnt1 expression by activating microRNA-34a (miR-34a)24, we wondered whether this microRNA may be involved in the regulation of Wnt1, Wnt6 and Wnt7a. Indeed, we observed p53 chromatin binding at the miR-34a locus in all cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Overexpression of miR-34a in WEA;Trp53–/– cells resulted in a significant reduction of Wnt ligand expression (Extended Data Fig. 7d). These data suggest that wild-type p53 negatively regulates the expression of Wnt1, Wnt6 and Wnt7a via miR-34a.

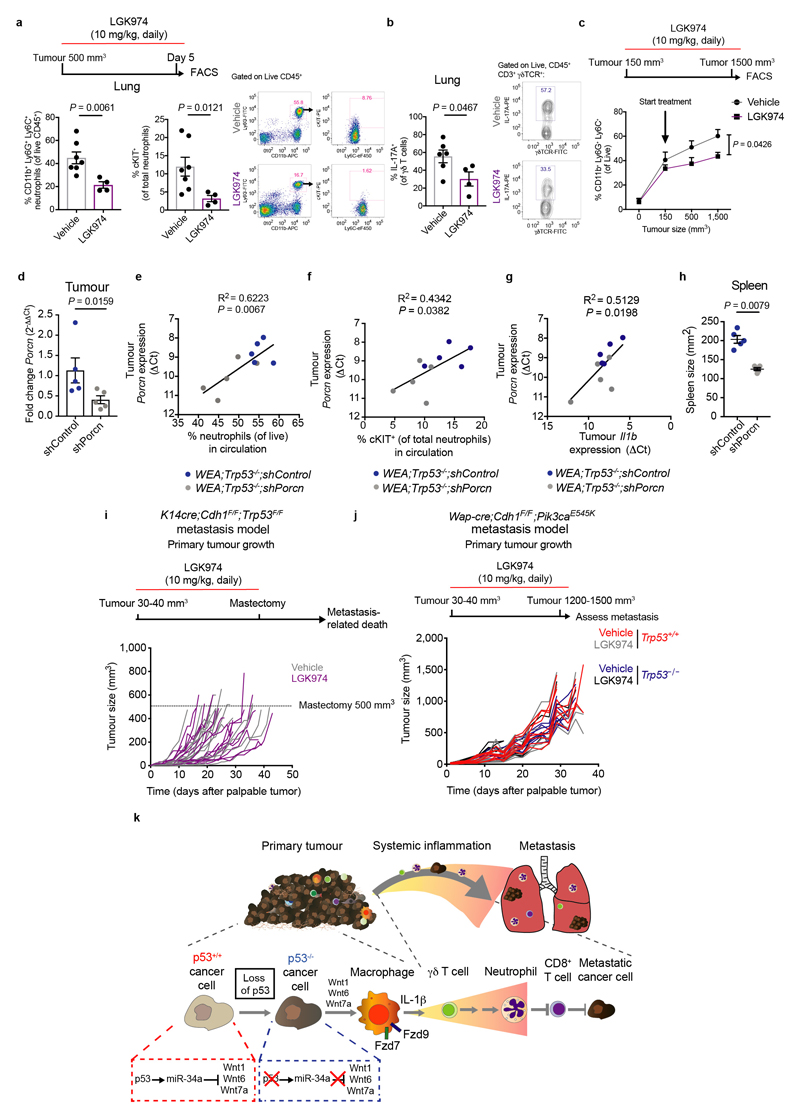

We then assessed the role of cancer cell-derived Wnt ligands on IL-1β production by macrophages. We treated WEA cells with LGK974 – which inhibits Porcupine (Porcn), a Wnt-specific acyltransferase that regulates Wnt ligand secretion25 – and added CM to macrophages. LGK974 reduced the WEA;Trp53–/– cell-induced Il1b expression by macrophages (Fig. 4a). We also depleted Porcn in WEA;Trp53–/– cells using short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) and knockdown reduced Il1b expression by macrophages, consistent with pharmacological Porcupine inhibition (Fig. 4a). These data confirm a causal relationship between Wnt ligand secretion by p53-deficient cancer cells and IL-1β expression in macrophages.

Figure 4. Wnt-induced systemic inflammation promotes metastasis of p53-null tumours.

a. RT-qPCR analysis of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) after exposure to control medium or conditioned medium from Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53+/+ (WT), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53–/– (KO) or Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53–/– cells transduced with 2 independent shRNAs against Porcn (KO shPorcn-1 and KO shPorcn-4). Where indicated, cell lines were pre-treated with 1 µM LGK974 (KO + LGK974) (n=5 biological replicates/group for WT, WT + LGK974, KO and KO + LGK974, n=3 biological replicates for KO shPorcn-1 and KO shPorcn-4). Plots show representative data of 3 separate experiments with 2 technical replicates per biological replicate. b. Frequency of total CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ neutrophils and cKIT+ neutrophils in circulation of K14cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F (KEP) mice after 5 day LGK974 (n=4) or vehicle (n=7) treatment starting at tumour volume 500 mm3. c. Number of pulmonary metastases after KEP tumour-bearing mice were treated with LGK974 (n=15) or vehicle (n=12). KEP tumour fragments were orthotopically transplanted in FVB/N mice and treatment was initiated when tumours were 30 – 40 mm3 and continued until primary tumour removal. d. Representative images of cytokeratin-8 staining of lungs of KEP tumour-bearing mice. Scale bars, 1.9 mm. e. Number of pulmonary metastases after orthotopic injection of Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP) cells and treatment with LGK974 or vehicle (n=9/group). Treatment was initiated when tumours were 30 – 40 mm3 and continued until 1500 mm3. f. Representative images of cytokeratin-8 staining of lungs of WEP tumour-bearing mice, arrows indicate examples of metastatic nodules. Scale bars, 1.4 mm. All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple-testing correction (a) or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (b, c, e), ns: non-significant.

To identify the receptors involved in the crosstalk between p53-null cancer cells and macrophages, we looked for genes encoding Wnt receptors in the GEMM gene expression data. We found that Frizzled receptors, Fzd7 and Fzd9, were up-regulated in the p53-null tumours compared to p53-proficient tumours (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Similarly, FZD7 and FZD9 were increased in expression in TP53MUT human breast tumours compared to TP53WT tumours (Extended Data Fig. 8b). We then used small interfering RNAs (siRNA) to knockdown both Fzd7 and Fzd9 in BMDMs (Extended Data Fig. 8c), which prevented Il1b induction by WEA;Trp53–/– cells (Extended Data Fig. 8d), demonstrating that that FZD7 and FZD9 are involved in Wnt-induced activation of macrophages in vitro.

We next assessed whether Wnt ligand production by p53-deficient cancer cells drives systemic inflammation. We treated tumour-bearing KEP mice with LGK974 for five consecutive days and this led to a reduction in total neutrophils and cKIT+ neutrophils in blood and lungs when compared to vehicle-treated KEP mice (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 9a). Additionally, IL-17A-producing γδ T cells – the key cell type responding to IL-1β that drive neutrophil accumulation and consequently metastasis5 – were reduced in the lungs of LGK974-treated KEP mice (Extended Data Fig. 9b), indicating that γδ T cell activation upstream of pro-metastatic neutrophil accumulation depends on Wnt signalling. Similarly, long-term treatment of KEP mice with LGK974 blocked neutrophil expansion over time (Extended data Fig. 9c). To exclude that the observed reduction in inflammation is a result of targeting non-tumour cells by LGK974, we orthotopically transplanted WEA;Trp53–/–;shPorcn cell lines and matched WEA;Trp53–/–;shControl cells into WT mice. Analysis of size-matched end-stage tumours revealed an incomplete reduction of Porcn expression (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that non-cancer cells contribute to the residual Porcn expression, expression levels of Porcn in the tumours correlated with circulating neutrophils, cKIT+ neutrophils and Il1b expression (Extended Data Fig. 9e–g). Moreover, knockdown of Porcn prevented splenomegaly (Extended Data Fig. 9h). Collectively, these data confirm the causal link between Wnt secretion triggered by p53-deficient mammary tumours and systemic inflammation.

Since the γδ T cell–neutrophil axis promotes metastasis4,5 and these cells are regulated by Wnt ligands, we hypothesized that LGK974 treatment may present a viable therapeutic strategy to inhibit metastasis of p53-null mammary tumours. To test this, we treated KEP tumour-bearing mice with LGK974 or vehicle, after which we surgically removed the primary tumour and assessed metastatic progression. Strikingly, while Porcupine blockade did not affect primary tumour growth (Extended Data Fig. 9i), pulmonary metastases were reduced (Fig. 4c, d). In an independent metastasis model in which we orthotopically transplanted matched Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– WEP cell lines, we observed that the absence of p53 increases lung metastasis formation (Fig. 4e, left and right graphs; P=0.0153). We then treated both WEP;Trp53+/+ and WEP;Trp53–/– tumour-bearing mice with LGK974, which failed to influence primary tumour growth (Extended Data Fig. 9j). However, LGK974 treatment reduced metastasis of WEP;Trp53–/– tumours, without affecting metastasis of WEP;Trp53+/+ tumours (Fig. 4e, f). These data show that blocking Wnt-induced systemic inflammation impedes metastasis formation of p53-null mammary tumours.

In summary, we show that p53 status is an important driver of systemic pro-metastatic inflammation in breast cancer (Extended Data Fig. 9k) and that targeting Wnt signalling may represent a promising therapeutic modality for patients with p53-deficient breast tumours. Together with recent literature on the importance of canonical driver mutations in shaping the local immune composition of primary tumours26, our findings shed light on the poorly understood inter-patient heterogeneity in the systemic composition and function of immune cells. Mechanistic understanding of the intricate interactions between cancer cell-intrinsic genetic events and the immune landscape provides a basis for the design of personalized immune intervention strategies for cancer patients.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute and performed in accordance with institutional, national and European guidelines for Animal Care and Use. The generation and characterization of the mouse models has been described27–34 (and unpublished). The following mouse models were used in this study: Keratin14 (K14)-cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F, K14cre;Trp53F/F, K14cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F, Whey Acidic Protein (Wap)-cre;Trp53F/F, Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F, Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Met-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F;Met), Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Myc-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Brca1F/+;Trp53F/F;Myc), Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Myb2-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Brca1F/F;Trp53F/F;Myb2), Wap-cre;Trp53F/F;Col1a1invCAG-ESR1-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Trp53F/F;HA-ESR1), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Col1a1invCAG-AktE17K-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Pik3caE545K-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/+;Col1a1invCAG-Fgfr2ex1-15-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/+;Fgfr2ex1-15), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Fgfr2ex1-15-IRES-Luc/+ (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Fgfr2ex1-15), Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;T2/Onc;Rosa26Lox66SBLox71/+ (Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;SB), Wap-cre;Map3k1F/F;PtenF/F, Mouse mammary tumour virus LTR (MMTV)-NeuT. All mouse models were on FVB/N background, except MMTV-NeuT and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;SB, which were on Balb/c and a mixed genetic (C57BL/6J and FVB/N) background, respectively. Female mice were monitored twice weekly for the onset of spontaneous mammary tumour formation by palpation starting at 6-7 weeks of age. The perpendicular tumour diameters of mammary tumours were measured twice per week using a calliper, and tumour volume was calculated using vol(mm3) = 0.5(length × width2). Maximum permitted tumour volumes were 1500 mm3. Age-matched WT littermates were used as controls. Average systemic total and cKIT+ neutrophil levels in non-tumour-bearing FVB/N and Balb/c mice were similar (data not shown). For orthotopic transplantation experiments, 1×106 cells were injected into the right 4th mammary fat pad of WT FVB/N mice (Janvier Labs). For intervention studies targeting Porcupine, K14cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F mice were treated daily with LGK97435 (10 mg/kg, in 10% DMSO/10% Cremophor in PBS) or vehicle (10% DMSO/10% Cremophor in PBS) via oral gavage, starting at matched tumour sizes indicated in the figures. For metastasis experiments, the KEP-based model for spontaneous breast cancer metastasis was used as previously described36. Briefly, tumour fragments of K14cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F mice were orthotopically transplanted into FVB/N mice and surgically removed when tumours reached 500 mm3 in size. In this model, LGK974 treatment was initiated when tumours were 30 – 40 mm3 in size and continued until mastectomy, after which mice were monitored for signs of metastatic disease. Disease endpoint was defined as mice showing signs of respiratory distress or palpable metastatic nodules in lymph nodes or other organs reaching 1500 mm3 in size. For metastasis experiments using the Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K model, matched Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– tumour-derived cell lines were orthotopically injected in the mammary fat pad of FVB/N mice (1×106 cells) and tumours were allowed to grow out until end stage (1500 mm3). During this time, tumours spontaneously metastasize to the lungs. LGK974 or vehicle treatment was initiated when tumours were 30 – 40 mm3 and continued until end stage. Orthotopically transplanted Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K tumours did not spontaneously metastasize before the primary tumours reached 1500 mm3, and surgical removal of the primary tumours was hampered by their highly invasive growth. For intervention studies, mice were randomly distributed over the two treatment arms when tumours reached the indicated size. Tumour measurements and post mortem analyses were performed in a blinded fashion. Mice were kept in individually ventilated cages, and food and water were provided ad libitum. The maximal permitted disease endpoints were not exceeded in any of the experiments.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was performed as previously described5. Briefly, tissues were collected in ice-cold PBS and blood was collected in tubes containing heparin. Tumours and lungs were mechanically chopped using a McIlwain tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratory Engineering). Tumours were digested for 1 hour (h) at 37°C in 3 mg/mL collagenase type A (Roche) and 25 µg/mL DNase (Sigma) in serum-free DMEM medium. Lungs were digested for 30 minutes (min) at 37°C in 100 µg/mL Liberase TM (Roche). Enzyme reactions were stopped by addition of cold DMEM/8% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) and suspensions were dispersed through a 70 µm cell strainer. Bone marrow was collected from the tibia and femurs of both hind legs and flushed using RPMI/8% FCS through a 70 µm cell strainer. Single-cell suspensions were treated with NH4Cl erythrocyte lysis buffer. Before staining, cell suspensions were subjected to Fc receptor blocking (rat anti-mouse CD16/32, BD Biosciences) for 15 min at 4°C, except for bone marrow (to allow assessment of CD16/32 expression). Cells were stained with conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4°C in the dark in PBS/0.5% BSA. 7AAD (1:20; eBioscience/ThermoFisher) or Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (1:1000; eBioscience/ThermoFisher) was added to exclude dead cells. For intracellular cytokine staining, single-cell suspensions were stimulated in IMDM containing 8% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol, 50 ng/ml PMA, 1 mM ionomycin and Golgi-Plug (1:1,000; BD Biosciences) for 3h at 37°C. Surface antigens were stained first, followed by fixation and permeabilization using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) and staining of intracellular proteins. All antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. All experiments were performed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer using Diva software or the Beckman Coulter CyAn ADP flow cytometer using Summit software. Data analyses were performed using FlowJo Software version 9.9.

Cell culture

Mouse cell lines were generated as follows: Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K (WEA) and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP) tumour material was collected in ice-cold PBS and mechanically chopped using a McIlwain tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratory Engineering). Tumours were subsequently digested for 30 min at 37°C in 3 mg/mL Collagenase A, 0.1% trypsin and fungizone in DMEM/2% FCS. Enzyme reactions were stopped by addition of DMEM/2% FCS and suspensions were dispersed through a 40 µm cell strainer. Cells were initially cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, Insulin, EGF and Cholera toxin. After establishment, mouse cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 8% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. To ensure relatedness to parental GEMM tumours, polyclonal cells were used at low passage number for all experiments. MCF-7 cells (provided by T.N. Schumacher) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 8% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination and only mycoplasma-negative cells were used. For in vitro culture of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), bone marrow was aseptically collected by flushing tibia and femurs from euthanized WT mice with sterile RPMI/8% FCS. Bone marrow cells were cultured for 7 days in RPMI medium supplemented with 8% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 10 ng/mL recombinant M-CSF (Peprotech). BMDMs were harvested at day 7 and examined for CD11b and F4/80 expression by flow cytometry. Consistent purities of >95% CD11b+F4/80+ cells were obtained. For in vitro culture of human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), human PBMCs (Sanquin, Amsterdam) were enriched by magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS) using CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD14+ cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 8% FCS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 10 ng/mL recombinant M-CSF (Peprotech). MDMs were harvested at day 7 and examined for CD11b, CD14 and CD68 expression by flow cytometry. Consistent purities of >95% CD11b+CD14+CD68+ cells were obtained. Where indicated, BMDMs and MDMs were exposed to conditioned medium (CM) from tumour cell lines, in presence or absence of LGK974 (1 µM, Selleck Chemicals) for 24 h and harvested for RNA and/or protein isolation. CM was obtained by culturing tumour cells at equal confluency in empty DMEM overnight. Cell growth kinetics in vitro were analysed using the IncuCyte System (Essen BioScience).

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using either Trizol or a Qiagen Rneasy column followed by treatment with Dnase I (Invitrogen). RNA quality was confirmed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer from Agilent. RNA was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) with an AMV reverse transcriptase using Oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). cDNA (20 ng per well) was analysed by SYBR green real-time PCR with 500 nM primers using a LightCycler 480 thermocycler (Roche). β-actin and/or GAPDH were used as reference genes. Primer sequences used for each gene are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Fold change in expression was calculated using 2–(ΔCt.x – average[ΔCt.control]).

Protein isolation and western blotting

Protein lysates of cells and tissue were prepared using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA) complemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche) and protein concentration was quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Protein lysate was loaded onto NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Mini or Midi Nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad) using Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (BioRad). Membranes were blocked in 10% Western Blot Blocking Reagent (Roche) or 3% BSA for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Primary antibody incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed using TBS-T and subjected to secondary fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 1 h at RT and protein was detected using the Odyssey CLx imaging system and processed using ImageJ software 1.48v. Antibodies are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed by the Animal Pathology facility at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. Formalin-fixed tissues were processed, sectioned and stained as described36. Briefly, tissues were fixed for 24 h in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological evaluation. H&E slides were digitally processed using the Aperio ScanScope (Aperio, Vista, CA). For immunohistochemical analysis, 5 μm paraffin sections were cut, deparaffinised and stained. Antibodies and antigen retrieval methods are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Quantitative analysis of cell abundance was performed by counting cells in five high-power (x40) fields of view (FOV) per tissue by two independent researchers. Samples were visualized with a BX43 upright microscope (Olympus) and images were acquired in bright field using cellSens Entry software (Olympus). To score pulmonary metastasis, single lung sections were stained for cytokeratin-8 and metastatic nodules were counted by two independent researchers. Stained tissue slides were digitally processed using the Aperio ScanScope. Brightness and contrast for representative images were adjusted equally among groups.

Cytokine analyses

Quantification of cytokine and chemokine levels in serum was performed using BD Cytometric Bead Array for CCL2, IL-1β, IL-17A and G-CSF according to manufacturer’s instructions and analysed on a Beckman Coulter CyAn ADP flow cytometer with Summit software. Data analyses were performed using FlowJo Software version 9.9.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption

For knock-out of murine Trp53, p53-proficient tumour cell lines were transfected with lentiCRISPR v2 (provided by F. Zhang (Addgene plasmid #52961)37) containing sgRNA targeting exon 4 (sgRNA1: 5’- TCCGAGTGTCAGGAGCTCCT-3’ and sgRNA2: 5’- AGTGAAGCCCTCCGAGTGTC-3’). For knock-out of human TP53, MCF-7 tumour cell lines were transfected with lentiCRISPRv2 containing sgRNA targeting either exon 4 (sgRNA1: 5’-CCATTGTTCAATATCGTCCG-3’) or exon 2 (sgRNA2: 5’-TCGACGCTAGGATCTGACTG-3’). Cloning of sgRNAs in lentiCRISPR was performed as described37 and sgRNA sequences were designed using the online CRISPR Design tool (http://crispr.mit.edu), of which the two highest scoring sequences were chosen. All vectors were validated by Sanger sequencing. After selection of transfected cells, polyclonal cell lines were used for all subsequent experiments. To determine knock-out efficiency, genomic DNA from cell lines was isolated using Viagen DirectPCR Lysis reagent (Cell) supplemented with 200 µg/mL proteinase K after transfection and puromycin selection. Murine Trp53 target region was amplified using PCR with the following primers: FW 5’-GGGGACTGCAGGGTCTCAGA-3’ and RV 5’-CCACGTCCCCTGGAGAGATG-3’. Human TP53 target region was amplified using PCR with the following primers: FW1 5’-CAGACTGCCTTCCGGGTCAC-3’ for sgRNA1, FW2 5’-TGGGAAGGTTGGAAGTCCCTC-3’ for sgRNA2, and RV 5’-CACTGACAGGAAGCCAAAGGG-3’. PCR products were run on 1% agarose gel, purified using the Illustra GFX™ PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Sigma), and subjected to Sanger sequencing using their respective FW primers. Genome editing efficiency was quantified using the Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) algorithm as described (http://tide.nki.nl)38.

shRNA- and siRNA-mediated knock-down of genes

Vectors for shRNAs were collected from the TRC library. To allow stable expression of shRNAs, HEK293T cells (provided by T.N. Schumacher) were transfected with the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector encoding shRNAs, pPAX packaging vector and VSV-G envelope vector. Five independent shRNA clones were used for each experiment. Virus was harvested at day 4 and 5 and viral titres were determined using the Abm qPCR lentivirus titration kit (LV900). Cells lines were subsequently transduced and selected using puromycin. Knock-down efficiency was determined by RT-qPCR as compared to non-targeting controls. The shRNA clone used for Porcupine knock-down in all experiments after assessment of knock-down efficiency contained following hairpin sequence: 5’-CAACTTTCTATGCCTGTCAAT-3’ (shPorcn-1) or 5’-CCCATGTCTTATTGGTTAAAT-3’ (shPorcn-4). For in vivo experiments, shPorcn-4 was used. To silence Fzd receptors, BMDMs were transfected with the following siRNA pools (control siRNA (sc-37007), Fzd7 (sc-39991), and Fzd9 (sc-39995), Santa Cruz Biotechnology), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, BMDMs were differentiated as described above, and 24 h before exposure to tumour CM and BMDMs were suspended in transfection medium and incubated with indicated siRNA pools. After 6 h at 37°C, 2X RPMI medium was added (RPMI, 20% serum, 200 IU/mL penicillin, 200 mg/mL streptomycin and 20 ng/mL recombinant M-CSF) and BMDMs were further cultured overnight. After 24 h, the medium was replaced by tumour CM for 24 h, after which gene expression was assessed.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-sequencing

ChiP-seq was performed as previously described39. Briefly, cell lines from Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K tumours (3 cell lines from 3 independent mouse tumours per genotype) were fixed in 1% formaldehyde, crosslinked and processed for sonication. 5 µg of p53 antibody (Supplemental Table 1) and 50 µL of Protein G magnetic beads (Invitrogen) were used for each ChIP. Eluted DNA was sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 2500 analyser (using 65 bp reads) and aligned to the Mus musculus mm10 reference genome. Peak calling over input control was performed using and MACS 2.0 peak caller. Data was visualized using Easeq40.

Overexpression of miR-34a

The MSCV-miR-34a retroviral vector (provided by Lin He (Addgene plasmid #63932)41) was transfected in HEK293T cells, together with pGag-Pol and VSV-G vectors to generate retrovirus. Mouse cancer cell lines were exposed to viral supernatant and assessed for expression of Wnt target genes after puromycin selection.

RNA sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tumours using TRIzol reagent (Ambion Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were equimolar pooled and were single-end sequenced for 51 or 65 base pairs on the Illumina Hiseq2000/Hiseq2500 Machine. The reads were aligned against the mouse transcriptome (mm10) using Tophat2 (Tophat version 2.1.0 / Bowtie version 1.0.0) that allows for exon-exon junctions42,43. Tophat was guided using a reference genome as well as a reference transcriptome. The reference transcriptome was created using a gene transfer file (GTF) that was downloaded from Ensembl (version 77). Gene counts were generated using a custom script, that functions identically to HTSeq-count44. Only reads that mapped uniquely to the transcriptome were used for gene expression quantification. While some of the libraries were generated with strand-specific protocols, all samples have been aligned without taking strandedness into account. Next, differential expression analysis was performed using the R package edgeR45 in combination with the voom46 method, using raw read counts as input. Library size normalisation was performed during differential expression analysis within the voom function. Genes with P-values < 0.05 were labelled as differentially expressed. Genes were further filtered for display by requiring them to be protein coding and to have an absolute log2 fold change ≥ 3 and a P-value ≤ 0.01. The selected genes were shown in a heatmap of readcounts that were normalized to 10 million reads per sample.

For Hallmark pathway analysis of murine transcriptomes, raw read counts were normalised by trimmed means of M-values computed using the function calcNormFactors (edgeR version 3.20.545), from which CPM-normalized gene expression values were computed for plotting purposes using the same R-package. CPM-values were subsequently transformed as f(x) = log2(x + 1). Ensembl77 murine gene identifiers were then converted to homologous human gene identifiers using the biomaRt-R package (server oct2016.archive.ensembl.org). Gene expression heatmaps for hallmark human gene sets obtained from MsigDB47 were generated using the aheatmap-function provided by the NMF R-package (version 0.20.6). Heatmap columns (containing samples) were ordered according to average linkage (UPGMA) hierarchical sample-clustering based on Pearson correlation-distances between the expression values of displayed genes. Heatmap rows (containing genes) were ordered according to gene expression fold difference between Trp53—/— and Trp53+/+ samples. The R language for statistical computing was used (version 3.4.2) for gene expression normalisation and heatmap generation. Pathway enrichment analysis of Trp53—/— and Trp53+/+ tumours was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (QIAGEN), analysing differentially expressed genes with P ≤ 0.05.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis

To obtain a comprehensive view on the cellular processes affected by p53-deficiency in human breast cancer, we performed a gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) using a 50 hallmark gene sets (Liberzon)47 on the TCGA breast cancer (BRCA) cohort. First, we classified p53-deficiency based on mutational status. DNA sequencing variant calls (MAF-file) for the BRCA cohort were downloaded from the 2015-08-21 release of the Broad TCGA genome data analysis centre standard run (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/stddata). We utilized two classifications for p53-deficiency: in the first classification (labelled ‘any TP53 mutation’), patients with any kind of TP53 mutation were classified as p53-deficient. In the second classification (labelled ‘IARC TP53 database’), only patients with a dominant negative TP53 mutation as annotated using the IARC TP53 mutation database48 (release 18, matched on protein effect of the mutation) were labelled as p53-deficient, as well as patients with gain-of-stop, stop-lost or frameshifting mutations (n=161). One sample had a trans-activating mutation and was excluded from the analysis. The remaining samples were labelled as p53-proficient (n=793).

Next, TCGA RNA sequencing data were downloaded from the Broad TCGA genome data analysis centre 2015-11-01 release of the standard runs. We ran a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the 50 Hallmark gene set using the flexgsea-r R package (https://github.com/NKI-CCB/flexgsea-r) on the read counts normalized with limma voom with the span parameter set to 0.546. Within each permutation of the sample labels, genes were ranked for association with p53-proficiency using the moderated t-statistic from the limma empirical Bayes function (ebayes() ran on the result of lmFit()). Reported FDR-values were obtained from the flexgsea-r output.

Single gene associations with TP53 status in human breast tumours of the TCGA BRCA cohort and correlation coefficients between WNT-related genes and TP53 status (MUT vs WT) were analysed using R2 Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl/) and visualized using GraphPad Prism version 7.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7). The statistical tests used are described in figure legends. All tests were performed two-tailed. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All western blot and RT-qPCR analyses were independently repeated more than twice. Sample sizes were based on previous experiments5,17,36 or determined using G*Power software (version 3.1). To exclude bias towards one particular GEMM in the analyses for Figure 1, we have performed the same analyses on the average of the neutrophil levels and serum cytokine values per model. This demonstrated the same correlations between the assessed values and p53 status of the tumour, thus excluding bias towards one or several particular models. Principal component analysis was performed using the prcomp-function in R (version 3.4.2), both centering and scaling the input data before applying dimensionality reduction.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Neutrophil expansion in p53-deficient tumour-bearing GEMMs.

a. Representative plots of flow cytometry analysis on blood of end-stage (cumulative tumour size 1500 mm3) mammary tumour-bearing mice. Neutrophils were defined as CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+. cKIT expression on gated total neutrophils in blood is shown (gating was based on blood of WT mice). Quantification and statistical analysis of these data is found in Fig. 1a, b

Extended Data Figure 2. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption of Trp53 in Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K cancer cell lines.

a. Insertion and deletion (indel) spectrum of bulk Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K (WEA) cancer cell lines after transfection with 2 individual sgRNAs against Trp53 and puromycin selection, as determined by the TIDE algorithm and compared to the sequence of target region of control cells. The P-value associated with the estimated abundance of each indel is calculated by a two-tailed t-test of the variance–covariance matrix of the standard errors. b. Western blot analysis showing p53 levels of control and p53-knockout (KO) WEA cell lines. Inactivation of the p53 pathway is shown by loss of p21 staining after 10 Gy irradiation. KO1 (sgRNA1) resulted in a truncated p53 protein and KO2 (sgRNA2) shows absence of p53 protein. For all subsequent experiments, KO2 was used. Representative of two independent experiments. For uncropped images, see Supplemental Fig. 1. c. In vitro growth kinetics of WEA control and p53-KO cells, as determined by IncuCyte (n=7 technical replicates/group). d. In vivo growth kinetics of orthotopically transplanted WEA;Trp53+/+ (n=4 mice) and WEA;Trp53–/– (n=6) cancer cell lines, with t = 0 being the first day tumours were palpable. e. Indel spectrum of bulk Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP) cancer cell lines after transfection with sgRNA2 against Trp53 and puromycin selection, as determined by the TIDE algorithm. f. In vitro growth kinetics of WEP control and p53-KO cells, as determined by IncuCyte (n=7 technical replicates/group). g. In vivo growth kinetics of orthotopically transplanted WEP;Trp53+/+ (n=5) and WEP;Trp53–/– (n=5) cell lines, with t=0 being the first day tumours were palpable. h. Gating strategy to identify circulating neutrophils and their cKIT expression. i. Gating strategy to identify neutrophils in the lung. j. Representative images of spleens from mice bearing WEA;Trp53+/+ and WEA;Trp53–/– tumours and quantification of spleen area (length × width) at end-stage (tumour volume 1500 mm3) of mice bearing p53-proficient (n=4) and p53-deficient WEA (n=6) and WEP tumours (n=5/group). All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by Area Under the Curve followed by two-tailed Welch’s t-test (c, d, f , g) or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (j), ns: not significant.

Extended Data Figure 3. Haematopoiesis in p53-null tumour-bearing mice is skewed towards the development of neutrophils.

a. Schematic representation of neutrophil development in the bone marrow. b. Gating strategy of neutrophil progenitor populations in the bone marrow. Dot plot indicates the cKIT expression levels (median fluorescence intensity [MFI]) in promyelocytes compared to mature neutrophils (n=20 mice). c. Frequency of bone marrow progenitor populations in mice bearing end-stage Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53+/+ (n=9) and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53–/– (n=11) tumours, as determined by flow cytometry. d. Total live cells and total live progenitor population numbers per hindleg of mice bearing WEA;Trp53+/+ and WEA;Trp53–/– tumours (n=5/group). All data are ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test. Abbreviations: LSK (Lin–Sca1+cKIT+, which contain the LT-HSC (long-term haematopoietic stem cells), ST-HSC (short-term haematopoietic stem cells) and MPP (multipotent progenitors)), CMP (common myeloid progenitors), GMP (granulocytic and monocytic progenitors), MEP (megakaryocyte and erythrocyte progenitors).

Extended Data Figure 4. Macrophages are differentially activated by Trp53–/– mouse and human breast cancer cell lines.

a. Expression (median fluorescence intensity [MFI]) of CCR2, CCR6, CD206, CSF-1R, CXCR4 and MHC-II on live CD11b+F4/80+ bone marrow-derived macrophages after exposure to control medium or conditioned medium (CM) of Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53+/+ or Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K;Trp53–/– cell lines, as determined by flow cytometry (n=4 biological replicates/group). b. TIDE analysis of bulk MCF-7 cells after transfection with TP53-targeting sgRNAs and puromycin selection. For subsequent experiments, sgRNA1 was used. c. Expression (MFI) of CD206, CD163 and HLA-DR on human CD11b+CD14+CD68+ monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) after exposure to CM of MCF-7;TP53+/+ or MCF-7;TP53–/– (sgRNA1) cancer cells (n=3 biological replicates/group). d. RT-qPCR analysis showing IL1B expression in human CD11b+CD14+CD68+ MDMs after exposure to control medium (n=4 biological replicates) CM of MCF-7-TP53+/+ or MCF-7-TP53–/–cancer cells (n=5 biological replicates/group). Data are normalized to normal medium control. Plots shows representative data of 3 separate experiments and average with 2 technical replicates. All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple-testing correction.

Extended Data Figure 5. Transcriptome profile and composition of the local tumour immune landscape in breast cancer GEMMs.

a. Unsupervised clustering of top 200 most differentially expressed genes (P < 0.01, LFC > 3 or < –3) in mammary GEMM tumours as determined by RNA sequencing (n=145 tumours). Red bars indicate Trp53+/+ tumours, blue bars indicate Trp53–/– tumours. Full tumour genotype is displayed in legend and shown by indicated colours. b. Number of Ly6G+ neutrophils in the tumour (n=1, 4, 10, 2, 4, 3, 6, 13, 4, 22, 4 and 5 mice, top to bottom). c. Macrophage score as indicative of F4/80+ macrophage abundance in the tumour (n=2, 2, 4, 4, 4, 2, 3, 5, 4, 9, 5 and 4 mice, top to bottom). d. Number of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the tumour (n=3, 2, 5, 5, 7, 3, 7, 3, 5, 4, 4 and 5 mice, top to bottom). e. Number of CD4+ T cells in the tumour (n=3, 2, 5, 5, 7, 3, 7, 3, 5, 4, 4 and 5 mice, top to bottom). f. Number of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the tumour (n=3, 2, 5, 5, 7, 3, 7, 3, 5, 4, 4 and 5 mice, top to bottom). g. Ratio of CD8/Foxp3 cells in the tumour (n=3, 2, 5, 5, 7, 3, 7, 2, 5, 4, 4 and 5 mice, top to bottom). All data are means of 5 microscopic fields of view (FOV) per mouse as determined by IHC. Inserts show data combined according to p53 status of the tumour. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, FDR multiple-testing correction (a) or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (b – g).

Extended Data Figure 6. WNT-related gene activation correlates with loss of p53 in mouse and human breast tumours.

a. Heatmap showing that Trp53–/– (KO) GEMM tumours (n=77) cluster away from Trp53+/+ (WT) tumours (n=68) based on analysis of the Hallmark p53 pathway (represents positive control) and b. analysis of the Hallmark Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Analysis was performed on all tumours of Extended Data Fig. 5a. c. Log2 fold change expression of genes involved in Wnt signalling (P < 0.05) in Trp53–/– (n=77) and Trp53+/+ (n=68) GEMM tumours depicted in Extended Data Fig. 5a. Black bars indicate genes that positively regulate, or are generally increased with active Wnt signalling. Red bars indicate genes that negatively regulate, or are down-regulated with active Wnt signalling. d. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for Hallmark pathways in TCGA TP53WT breast tumours (n=643) vs TP53MUT (n=351) human tumours (any TP53 mutation) or TP53 loss (based on the IARC TP53 database, see Materials and Methods). Normalized enrichment score is shown with False Discovery Rate (FDR) indicated. e. Correlation coefficient (R) of all genes involved in WNT signalling that correlate significantly (P < 0.05) with TP53MUT (n=351) vs TP53WT (n=643) in TCGA breast tumours. Black bars indicate genes that positively regulate, or are generally increased with active WNT signalling. Red bars indicate genes that negatively regulate, or are down-regulated with active WNT signalling. P-values were determined by two-tailed ANOVA with FDR multiple-testing correction (c, e).

Extended Data Figure 7. p53 does not bind the regulatory regions of Wnt ligands directly.

a. Chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) profile of p53 binding to DNA demonstrating enrichment on the Cdkn1a (p21) locus in Trp53+/+ Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K (WEA) and Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP) cell lines (3 cell lines from 3 independent tumours per GEMM). b. Absence of p53 binding to Wnt1, Wnt6 or Wnt7a loci. c. Enrichment of p53 on microRNA-34a (miR-34a) locus. d. RT-qPCR analysis of Wnt ligand expression in WEA;Trp53+/+ and WEA;Trp53–/– cell lines after overexpression (OE) of miR-34a in WEA;Trp53–/–cells (n=3 technical replicates/group). Plots show representative data of 3 separate experiments with 3 technical replicates. All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey multiple-testing correction (d).

Extended Data Figure 8. Macrophages are activated by Trp53–/– cancer cells via Fzd7 and Fzd9 receptors in vitro.

a. Log2 fold change in expression of Wnt receptors Fzd7 and Fzd9 in bulk tumours comparing Trp53–/– (n=77) and Trp53+/+ (n=68) GEMM tumours using RNA-sequencing. b. Expression of FZD7 and FZD9 in TP53 wild-type (WT, n=643) and TP53 mutant (MUT, n=351) human breast tumours of TCGA dataset. c. Silencing of Fzd7 and Fzd9 in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) after transfection with siRNA pools against both receptors, as determined by RT-qPCR (n=6 biological replicates/group). d. Expression of Il1b in BMDMs after exposure to conditioned medium of Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;AktE17K cell lines (n=6 biological replicates/group), as determined by RT-qPCR. Where indicated, BMDMs were transfected with control siRNA or Fzd7/9 siRNA pools. a, c, d show means ± s.e.m. b. shows 5 – 95 percentile boxplot with median and quartiles indicated. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed one-way ANOVA, FDR multiple-testing correction (a), two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (b) or two-tailed one-way ANOVA, Tukey multiple-testing correction (d).

Extended Data Figure 9. Pharmacological and genetic targeting of Porcupine in p53-deficient tumours reduces systemic inflammation.

a. Total and cKIT+ neutrophil frequencies in lungs of vehicle (n=7) or LGK974 (n=4)-treated K14cre;Cdh1F/F;Trp53F/F (KEP) mice using indicated 5 day short-term treatment schedule. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. b. Frequency of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in lungs of vehicle (n=6) or LGK974 (n=4)-treated KEP mice. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. c. Kinetics of circulating neutrophils in vehicle or LGK974-treated KEP mice using indicated long-term treatment schedule, shown as frequency at indicated tumour volumes (n=8/group). d. RT-qPCR analysis of Porcn expression in end-stage bulk tumour (n=5/group). Data are normalized to shControl and represents an average of 2 technical replicates. e. Correlation of total neutrophil levels in circulation with expression of Porcn in WEA;Trp53–/–;shControl and WEA;Trp53–/–;shPorcn whole tumour lysate (n=5/group). f. Correlation of cKIT+ neutrophil levels in circulation with expression of Porcn in WEA;Trp53–/–;shControl and WEA;Trp53–/–;shPorcn whole tumour lysate (n=5/group). g. Correlation of Porcn expression and Il1b expression in bulk WEA;Trp53–/–;shControl (blue) and WEA;Trp53–/–;shPorcn tumours (grey) (n=5/group). Data represent an average of 2 technical replicates. h. Spleen area in mice with WEA;Trp53–/–;shControl (blue) and WEA;Trp53–/–;shPorcn tumours (grey) tumours at end-stage (n=5/group). i. Growth kinetics of orthotopically transplanted KEP mammary tumours, treated with vehicle (n=12) or LGK974 (n=15). Each line represents an individual mouse. j. Growth kinetics of orthotopically injected Trp53+/+ and Trp53–/– Wap-cre;Cdh1F/F;Pik3caE545K (WEP) cells, treated with vehicle or LGK974. Each line represents an individual mouse (n=9/group). k. Schematic representation of the findings of this study: loss of p53 in breast cancer cells triggers secretion of Wnt ligands to activate tumour-associated macrophages. This stimulates systemic expansion and activation of neutrophils, which we have previously shown to be immunosuppressive5, thus driving metastasis. All data are means ± s.e.m. P-values are indicated as determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (a – d, h), linear regression analysis (e – g) and area under the curve of average growth curves, followed by two-tailed Welch’s t-test (i, j).

Acknowledgements

Research in the De Visser laboratory is funded by a European Research Council Consolidator award (ERC InflaMet 615300), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VICI 91819616), Oncode Institute, the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF10083; KWF10623) and the Beug Foundation for Metastasis Research. K.E.d.V. is an EMBO Young Investigator. We would like to thank members of the De Visser and Jonkers labs and R. Mezzadra for fruitful discussion during the preparation of the manuscript. We thank O. van Tellingen, the Mouse Clinic for Cancer and Aging (MCCA) intervention Unit, flow cytometry facility, mouse transgenic facility, genomics core facility, animal laboratory facility and animal pathology facility of the Netherlands Cancer Institute for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability statement

The RNA sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) repository under accession number GSE112665. All other data are found in the source data, supplemental information or available from the authors on reasonable request.

Author contributions

M.D.W., S.B.C., J.J. and K.E.d.V. conceived the ideas and designed the experiments. M.D.W., S.B.C., D.E.M.D. and M.H.v.M. performed the animal experiments, flow cytometry, RT-qPCR, serum analyses, western blot, immunohistochemistry and other experiments and analysed the data. C.H., K.V., A.P.D., E.S. and R.d.K-G. provided technical support and performed animal experiments. M.H.v.M., L.H., S.M.K. and J.J. generated mouse models. M.D.W. and R.d.K-G. performed mouse intervention experiments. I.v.d.H. generated the GEMM-derived cell lines. S.P., M.D.W. and W.Z. performed and analysed the ChIP-seq experiments. M.S., I.d.R., M.D.W., L.F.A.W. and T.N.S. performed the bioinformatics analyses on mouse and human RNA-sequencing datasets. M.D.W., S.B.C. and K.E.d.V. wrote the paper and prepared the figures, with input from all authors.

Competing interests

M.D.W., S.B.C., D.E.M.D., M.H.v.M., M.S., I.d.R., L.H., S.M.K., S.P., C-S.H. K.V., A.P.D., R.d.K-G., E.S. I.v.d.H., W.Z. and J.J. report no competing interests. L.F.A.W. reports research funding from Genmab. T.N.S. is a consultant for Adaptive Biotechnologies, AIMM Therapeutics, Allogene Therapeutics, Amgen, Merus, Neon Therapeutics, Scenic Biotech, Third Rock Ventures, reports research support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA, and is stockholder in AIMM Therapeutics, Allogene Therapeutics, Merus, Neogene Therapeutics, Neon Therapeutics, Scenic Biotech, all outside the scope of this work. K.E.d.V. reports research funding from Roche and is consultant for Third Rock Ventures, outside the scope of this work.

References

- 1.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493–503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAllister SS, Weinberg RA. The tumour-induced systemic environment as a critical regulator of cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:717–27. doi: 10.1038/ncb3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Templeton AJ, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffelt SB, et al. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–48. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowanetz M, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor promotes lung metastasis through mobilization of Ly6G+Ly6C+ granulocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21248–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bald T, et al. Ultraviolet-radiation-induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wculek SK, Malanchi I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;528:413–17. doi: 10.1038/nature16140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park J, et al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:361ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steele CW, et al. CXCR2 Inhibition Profoundly Suppresses Metastases and Augments Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:832–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ethier JL, Desautels D, Templeton A, Shah PS, Amir E. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:2. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooks T, et al. Mutant p53 prolongs NF-kappaB activation and promotes chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:634–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwitalla S, et al. Loss of p53 in enterocytes generates an inflammatory microenvironment enabling invasion and lymph node metastasis of carcinogen-induced colorectal tumors. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stodden GR, et al. Loss of Cdh1 and Trp53 in the uterus induces chronic inflammation with modification of tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2015;34:2471–82. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wörmann SM, et al. Loss of P53 Function Activates JAK2-STAT3 Signaling to Promote Pancreatic Tumor Growth, Stroma Modification, and Gemcitabine Resistance in Mice and is Associated With Patient Survival. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:180–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bezzi M, et al. Diverse genetic-driven immune landscapes dictate tumor progression through distinct mechanisms. Nat Med. 2018;24:165–75. doi: 10.1038/nm.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kersten K, et al. Mammary tumor-derived CCL2 enhances pro-metastatic systemic inflammation through upregulation of IL1beta in tumor-associated macrophages. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1334744. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1334744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annunziato S, et al. Modeling invasive lobular breast carcinoma by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated somatic genome editing of the mammary gland. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1470–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.279190.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X, et al. CD11b+/Gr-1+ immature myeloid cells mediate suppression of T cells in mice bearing tumors of IL-1beta-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8200–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh V, Holla S, Ramachandra SG, Balaji KN. WNT-inflammasome signaling mediates NOD2-induced development of acute arthritis in mice. J Immunol. 2015;194:3351–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avgustinova A, et al. Tumour cell-derived Wnt7a recruits and activates fibroblasts to promote tumour aggressiveness. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10305. 10305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. WNT/beta-catenin pathway activation correlates with immune exclusion across human cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim NH, et al. p53 and microRNA-34 are suppressors of canonical Wnt signaling. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra71. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Cancer-Cell-Intrinsic Mechanisms Shaping the Tumor Immune Landscape. Immunity. 2018;48:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boggio K, Nicoletti G, Di Carlo E, Cavallo F, Landuzzi L, Melani C, Giovarelli M, Rossi I, Nanni P, De Giovanni C, Bouchard P, et al. Interleukin 12–mediated Prevention of Spontaneous Mammary Adenocarcinomas in Two Lines of Her-2/neu Transgenic Mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:589–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonkers J, et al. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–25. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derksen PW, et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:437–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, et al. Somatic loss of BRCA1 and p53 in mice induces mammary tumors with features of human BRCA1-mutated basal-like breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702969104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henneman L, et al. Selective resistance to the PARP inhibitor olaparib in a mouse model for BRCA1-deficient metaplastic breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8409–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500223112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huijbers IJ, et al. Using the GEMM-ESC strategy to study gene function in mouse models. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1755–85. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kas SM, et al. Insertional mutagenesis identifies drivers of a novel oncogenic pathway in invasive lobular breast carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1219–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annunziato S, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies combinations of driver genes and drug targets in BRCA1-mutated breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2019;10:397. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08301-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20224–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doornebal CW, et al. A preclinical mouse model of invasive lobular breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:353–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11:783–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt D, et al. ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods. 2009;48:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lerdrup M, Johansen JV, Agrawal-Singh S, Hansen K. An interactive environment for agile analysis and visualization of ChIP-sequencing data. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:349–57. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada N, et al. A positive feedback between p53 and miR-34 miRNAs mediates tumor suppression. Genes Dev. 2014;28:438–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.233585.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liberzon A, et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouaoun L, et al. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:865–76. doi: 10.1002/humu.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]